Cal Newport's Blog, page 42

December 31, 2015

Resolve to Live a Deep Life

A Deep Omission

In preparation for the upcoming release of my new book, I’m doing a lot of interviews about deep work. This process of talking about depth again and again helped me identify a shortcoming in my treatment of this skill here on Study Hacks.

I realized that I spend a lot of time explaining the importance of intense focus and detailing strategies to help you focus better, but I’ve neglected the big picture questions about what it really means to prioritize this skill in your life; e.g.,

What are the major changes to your life required by a commitment to deep work?

What are the large scale goals you should be striving to achieve using the types of small scale habits and strategies I so often discuss?

What, in other words, is the sixty-second summary of what it means to live a deep life?

In this post, I’ll try to answer these questions…

A Deep Life

To me, to live a deep life is to embrace the following three general commitments:

You systematically train your ability to concentrate intensely. Focus is a skill that must be practiced, and therefore, most people are not very good at it. Those who train themselves to concentrate intensely, however, produce at a level that can seem superhuman to their peers.

To be more concrete: At any given point, you should be able to describe your current cognitive calisthenics routine just as you might describe your current exercise routine.

You build your workweek around protecting and supporting many occasions to work deeply. Most knowledge workers rarely stumble into long blocks of uninterrupted time in their schedule. If you want to work deeply on a regular basis, you have to fight for it. The deep life requires, in other words, that you invest the effort needed to hold back time for depth despite the ever-encroaching pressure of the shallow.

To be more concrete: Start with the goal of having five hours per week protected on your calendar for deep work. Each session should be at least 90 minutes long.

You take bold measures to demonstrate respect for your attention. Deep work wields your attention like a well-honed tool. To be serious about this craft you need to be serious about how you treat your attention, much like professional athletes are serious about their physical health. This might mean that you quit social media, or lock away your phone after dinner, or take up meditation, or spend more time outside each day. The details don’t matter as much as the intention.

To be more concrete: Make one non-trivial change in your life that demonstrates to yourself that you prioritize your attention over more superficial activities.

There are many ways to act on the three commitments above. Depending on your situation different strategies might be more appropriate than others.

For example: one way I train my focus is to regularly use an outdoor office; one way I protect deep work in my week is to schedule it on Monday morning on my calendar like any other inviolable appointment; and one way I demonstrate respect for my attention is that I’ve never had a social media account.

For some, my approach to the deep life might work well, while for others, it might be completely unworkable.

But what I strongly believe is that for most skilled knowledge work positions, if commit to the three general ideas above, and find ways to act on these commitments that work for your life, you will thrive — not only will you experience significantly more success, you’ll also find your work more meaningful and your mind less cluttered and anxious.

A Deep Resolution

I end my new book on deep work with a quote from science writer Winifred Gallagher:

“I’ll live the focused life, because it’s the best kind there is.”

As you make your New Year’s resolutions this week, consider accepting Gallagher’s conclusion and committing to depth. A deep life is a good life, if you’re willing to put in the effort.

(Photo by Hernan Pinera)

#####

A brief administrative note: On Wednesday, January 6th, at 3 pm ET, I’ll be doing a live Ask Me Anything chat for Product Hunt about my new book on deep work. This is a chance for you to ask me live any question you want about deep work, productivity, or any other topic. To attend simply go to this page at 3 pm ET on January 6th.

December 22, 2015

Final Chance to Learn How I Manage My Work

A Brief Reminder

A few weeks ago, I announced that on January 3rd, I’ll be hosting a webinar in which I’ll walk through all the details of how I integrate deep work into my professional life, and then answer your questions on the topic.

A few weeks ago, I announced that on January 3rd, I’ll be hosting a webinar in which I’ll walk through all the details of how I integrate deep work into my professional life, and then answer your questions on the topic.

To gain access to the webinar, you need to pre-order my new book DEEP WORK (readers in the UK should pre-order here), and then enter your information at this online form.

If you’re one of the 1300 people who have already signed up for this webinar, I want to thank you for supporting my new book and let you know that I look forward to speaking with you on the 3rd.

The purpose of this post, however, is to note that if you’re thinking about pre-ordering the book and signing up for the webinar, then you only have until Christmas Day to do so — as on the 26th I’m going to begin the process of exporting all the names of people who signed up from the form and into my webinar system, after which, it will be too late.

December 11, 2015

Deep Habits: The Danger of Pseudo-Depth

Depth Deception

A difficulty I’ve faced in promoting the practice of deep work is that many people think they engage in this activity regularly (and don’t get much out of it), even though what they’re really doing is far from true depth.

To better understand this possibility, consider the following two hypothetical scenarios:

Scenario #1: Alice has to write a difficult client proposal. She decides to work away from her office for the first half of the day. She begins by going for a long walk to clear her head and play around with the different proposal pieces. She ends up at the local library, where she settles into a quiet corner for an hour and tries to write a rough draft. She feels the pitch is still too muddled, so she walks to a nearby coffee shop for more caffeine and works the outline over and over on paper. Finally she hits a configuration she likes and returns to the library to work it into the draft. After another hour she has something special. For the first time that day, she checks her e-mail before heading into the office.

Scenario #2: Alice has to write a difficult client proposal. She checks her e-mail, sends off some replies, then drives into work. At the office she closes her door to work on the proposal. She finds it hard going, but sticks with for a couple hours. She only checks her e-mail a few times an hour during this period (much less than normal) and peeks at Facebook to relieve her boredom only once. She does take a break halfway through to gripe about an unrelated manner in the office kitchen with a colleague.

In both scenarios, Alice dedicated a good stretch of time to working on a cognitively demanding task. Many people, new to the concept, would therefore consider both scenarios to describe deep work.

But they would be wrong.

Pseudo-Depth

Here’s the key observation about this example: in the second scenario, Alice never went more than twenty minutes or so without switching her attention away from her primary task to something else. It’s tempting to dismiss these breaks because they’re so fleeting — lost in the standard background noise of knowledge work — but their cost is substantial.

Something that came up again and again when I was researching my book on this topic, is that switching your attention — even if only for a minute or two — can significantly impede your cognitive function for a long time to follow.

More bluntly: context switches gunk up your brain.

This effect has been validated from many angles in academic psychology and related fields, spanning the work of Bluma Zeigarnik, Clifford Nass, Gloria Mark and Sophie Leory (whose theory of attention residue I write more about here).

In the first scenario, by contrast, Alice gives herself the time required to really let her brain get up to speed on the demanding problem and then stay in high gear long enough to make progress.

Having studied and experimented with deep work for years, I can tell you with confidence that the session described in the first scenario has the potential to produce an outcome an order of magnitude more compelling and effective than what Alice could produce in the state of pseudo-depth described in the second scenario. The former also describes a more satisfying work experience.

I try to put aside one day per week to spend a stretch of six to seven hours straight without distraction — no e-mail, no Internet, lots of walking (some in the woods), too much coffee — all focused on a small number of crucial, hard work tasks. This week I managed this on two different days.

It was a good week.

The bottom line is that if you’re intrigued by depth, give real depth a try, by which I mean giving yourself at least two or three hours with zero distractions. Let the hard task sink in and marinate. Push through the initial barrier of boredom and get to a point where your brain can do what it’s probably increasingly craving in our distracted world: to think deeply.

(Photo by Luis Marina)

November 30, 2015

Tony Schwartz’s Internet Addiction (and Why You Should Care)

Schwartz’s Important Admission

Last weekend, Tony Schwartz published an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Addicted to Distraction.” It soon topped the list of the paper’s most e-mailed articles.

Schwartz begins the essay with an admission:

“I fell last winter into an intense period of travel while also trying to manage a growing consulting business. In early summer, it suddenly dawned on me that I wasn’t managing myself well at all, and I didn’t feel good about it.”

Determined to improve matters, he launched an “irrationally ambitious plan” to simultaneously correct multiple deficiencies in his lifestyle, spanning from excessive alcohol and diet soda consumption, to bad eating habits, to the addictive e-mail checking and web surfing that fragmented his day.

What struck me is what happened next…

Through great determination Schwartz was able to stop consuming both diet soda and alcohol. He also eliminated sugar and refined carbohydrates from his diet, and he began exercising regularly.

But there was an addiction he couldn’t shake. As he explains: “I failed completely in just one behavior: cutting back my time on the Internet.”

A New Beast

When attempting to dismiss the threat that tools like e-mail and social media pose to our attention (and perhaps even our sense of autonomy), Internet apologists like to point to previous “scares” that turned out to be not so scary.

Perhaps most common among these examples was the threat of television — a concern which reached its apex with Jerry Mander’s 1978 book, Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television.

But as Schwartz’s story confirms, the Internet is a more fearsome beast. It’s true that people perhaps spent too much time watching television. But, for the most part, people…

…didn’t bring their televisions to work and watch them so incessantly throughout the day that they lost their ability to complete demanding professional tasks at anywhere near their full potential.

…didn’t bring portable televisions on dates or to movies or to bowling night, and sneak so many glances that they had a hard time participating in the socialization.

…didn’t watch television out of the corner of their eye while trying to listen to a college lecture or keep glancing at the latest program while attempting to study in the library.

And so on.

My point is that we should no longer treat the impact of the Internet on our cognitive personhood as a quirky issue that is at best, to quote a commenter on the Schwartz article, a “tempest in a tea cup.”

There’s something serious going on when someone like Tony Schwartz, who has made a career helping people reach their full potential, has an easier time kicking alcohol and sugar than his compulsive Internet habit.

I don’t have a specific prescription to offer here. But I do predict that we’re heading toward an era where more drastic responses to this issue will become socially acceptable.

An era, perhaps, when tools that are engineered by highly-paid psychologists to form addictive attractions (ahem, Facebook) are widely shunned, and the idea that everyone has a single universal e-mail address that everyone can access for every reason seems absurd.

Or maybe the best response will look completely different. But the fact that a major response is needed is something that deserves more careful discussion.

Tony Schwartz would likely agree. He ends his piece by telling a story about how he recently found himself eating a meal with his family in a restaurant. As he ate, he noticed a man enter with an “adorable” child. As Schwartz recalls:

“Almost immediately, the man turned this attention to his phone. Meanwhile, his daughter was a whirlwind of energy and restlessness…[attempting many things] to get her father’s attention…she didn’t succeed and after a while, she glumly gave up.

The silence felt deafening.”

What more motivation do we need to begin considering radical solutions to an unacceptable status quo when it comes to the quality of our mental life?

November 27, 2015

I Want to Show You Exactly How I Prioritize Deep Work in My Busy Life

A Look Inside My Systems

I’m committed to the idea that deep work is the key to a successful and meaningful professional life. Not surprisingly, I back up this commitment with a complex set of battle-tested systems that ensure I spend a non-trivial amount of time in a state of intense depth each week.

At the moment, due to these systems, I average between 15 – 20 hours of deep work per week. I manage this even though I’m professor with a full course and service load, an active blogger and writer, a father of two young boys, and someone who rarely works in the evening.

Now I want to let (some of) you inside my world and explain exactly how I make this happen…

In more detail, I’m going to host an exclusive, invite-only webinar on Sunday, January 3rd where I will walk through the details of my deep work systems and answer any and all questions on this general topic from the webinar attendees.

Here’s the catch: invitations to the webinar will be limited to people who pre-order my new book DEEP WORK (which will be released on January 5th).

Here’s the catch: invitations to the webinar will be limited to people who pre-order my new book DEEP WORK (which will be released on January 5th).

Once you’ve pre-ordered the book (of if you’ve already done so): simply click here to access an online form where you’ll be asked to enter your e-mail address and some order confirmation information.

Once we’ve confirmed all the entries, I’ll e-mail this pre-order list the information needed to access the webinar. After the webinar, I’ll also send this pre-order list a full recording of the event for those who cannot attend live.

Why am I limiting this event to people who pre-order the book?

Pre-orders carry a great weight in the modern book business. Major retailers such as Barnes & Noble, for example, now use pre-order numbers to determine how seriously to take a new release.

I’m using this event, therefore, for two reasons:

To try to convince those who think they’ll buy the book anyway to consider pre-ordering it.

To thank those of you who have supported my efforts over the years to spread the gospel of deep work.

This offer will only be available for the next few weeks, as we’re planning on processing all the entries before the Christmas vacation. So if you’re thinking about taking advantage of this invitation, don’t procrastinate too much.

Enough about this. Now back to our regularly scheduled programming…

November 24, 2015

The Feynman Notebook Method

Feynman’s Exams

After his second year of graduate school at Princeton, Richard Feynman faced his oral examinations. Feynman was not yet the famous physicist he would soon become (as his biographer James Gleick put it, “His Feynman aura…was still strictly local”), so he took his preparation seriously.

Feynman drove up to MIT, a campus familiar from his undergraduate years, and a place “where he could be alone.” It’s what he did next that I find interesting.

As Gleick explains:

“[He] opened a fresh notebook. On the title page he wrote: NOTEBOOK OF THINGS I DON’T KNOW ABOUT. For the first but not last time he reorganized his knowledge. He worked for weeks at disassembling each branch of physics, oiling the parts, and putting them back together, looking all the while for the raw edges and inconsistencies. He tried to find the essential kernels of each subject.”

I might not have worked with any future Feynmans during my time at MIT, but I certainly had the privilege to watch the ascent of at least two or three future stars in the world of science. And one thing they all seemed to share with Feyman was his hunger to understand what he didn’t know.

If someone published something good, they wanted to understand it. If this good thing used some mathematical technique they didn’t know, they’d drop off the radar until they learned it. If you published an interesting result, they’d soon learn every detail and be able to replicate it easier than you could manage.

Their proverbial notebooks of things they don’t know where always growing, and as a result, they thrived.

The Feynman Notebook Method

I think there’s a general method lurking here. People resist learning hard things — be it a graduate student mastering fundamental physics or an online marketer taming a new digital analytics tool — because learning is hard and requires significant amounts of deep work.

Dedicating a notebook to a new learning task, however, can provide concrete cues that help you stick with this hard process.

At first, the notebook pages are empty, but as they fill with careful notes, your knowledge also grows. The drive to fill more pages keeps your motivation stoked.

(To see this Feynman Notebook Method in action, consider the image at the top of this post, which shows a page from the notes I took as part of my effort to learn the basics of information theory during a recent trip to San Sebastian, Spain.)

It’s a simple idea: translate your growing knowledge of something hard into a concrete form and you’re more likely to keep investing the mental energy needed to keep learning. But sometimes a simple idea is all it takes to unlock a new level of potential.

“When [Feynman] was done,” Gleick reports, “he had a notebook of which he was especially proud.”

You should seek that same pride in your own quest to become too good to be ignored.

November 20, 2015

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

A New Book

I’m excited to announce my new book, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World.

The book will be published on January 5th (though it’s available now for pre-order). In this post, I want to provide you a brief sneak peek.

My Deep Work Mission

If you’ve been reading Study Hacks over the past few years, you’ve witnessed my increasing interest in the topic of deep work, which I define to be the act of focusing without distraction on a cognitively demanding task.

I firmly believe that deep work is like a superpower in our current economy: it enables you to quickly (and deliberately) learn complicated new skills and produce high-value output at a high rate.

Deep work is also an activity that generates a sense of meaning and fulfillment in your professional life. Few come home energized after an afternoon of frenetic e-mail replies, but the same time spent tackling a hard problem in a quiet location can be immensely satisfying.

There’s a reason why the people who impress us most tend to be people who deployed intense focus to make a dent in the universe; c.f., Einstein and Jobs.

Focus is the New I.Q.

Which brings me to my new book…

Deep Work is divided into two parts. The first part is dedicated to making the case for this activity. In particular, I provide evidence that the following hypothesis is true:

The Deep Work Hypothesis.

Deep work is becoming increasingly valuable at the same time that it’s becoming increasingly rare. Therefore, if you cultivate this skill, you’ll thrive.

The second part of the book provides strategies for acting on this reality.

Drawing on my own habits, the habits of other adept deep workers, and reams of relevant science, I describe how to improve your ability to work deeply and how to make deep work a major part of your already busy schedule.

In this second part, you’ll also find detailed elaborations of some of my more well-known ideas on supporting deep work, from time blocking, to fixed-schedule productivity, to depth rituals — in addition to many more tactics that I’m revealing for the first time.

More Information

If you want to learn more about the book, the Amazon page includes the full flap copy as well as the nice endorsements it received from Dan Pink, Seth Godin, Matthew Crawford, Adam Grant, Derek Sivers and Ben Casnocha.

You can also read this extended excerpt on Medium that discusses how a star professor uses deep work to dominate his field.

The book will be released on January 5th but is available for pre-order today on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

November 16, 2015

Shonda Rhimes Doesn’t Check E-mail After 7 pm

A Fellow Dartmouth Alum Discusses E-mail

Not long into a recent Fresh Air interview with Shonda Rhimes, Terry Gross brings up the last subject you might expect: e-mail habits.

Rhimes, it turns out, has the following signature appended to all her e-mails:

I don’t read work e-mails after 7 pm or on weekends, and if you work for me, may I suggest you put down your phone?

Gross and Rhimes discussed the details and implications of this e-mail habit for over four minutes, which is more than a tenth of the entire interview.

Listening to this exchange, I was struck by three points which I think speak to some of the larger issues surrounding work and distraction in a digital age…

Point #1: People are really exhausted by e-mail

The fact that Terry Gross brought up this topic (out of nowhere) so early in the interview, and discussed it for so long, indicates just how important the negative impact of e-mail has become: it’s a universal issue for knowledge workers.

Point #2: People equate e-mail with work

Here’s Gross investigating the reality of Rhimes’s e-mail free evenings:

How do you do that? The work day doesn’t end until after seven for a lot of people, how do you manage to just turn it off after 7 o’clock and on weekends?

What strikes me about this question (and the conversation that followed) is that it equates reading and responding to e-mails with working. In Gross’s formulation, once you stop receiving e-mails for the day, you’re done working for the day. And Rhimes agreed.

I think they’re completely wrong on this point, but this misunderstanding goes a long way toward explaining e-mail’s pathology.

Point #3: E-mail is not nearly as important as we think

Shonda Rhimes is important. Lot’s of important things cross her plate. Many are urgent. She receives over 2500 work e-mails every day. And yet, as she explains:

That’s what I found so interesting, since turning off my phone at 7 pm there’s never been a thing so urgent that I regretted having my phone off.

Gross pushed back at this point, asking if Rhimes simply passed the buck by hiring underlings to answer her e-mails for her after 7, but Rhimes quickly dispelled the notion. She says she built a culture in her production company where you work during work hours and then you’re done.

A Strong Finale

I was perhaps most taken by the simple force with which Rhimes dismissed the culture of connectivity. Here’s her summation:

Work will happen 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year, if you let it. We are all in that place where we are all letting it for some reason, and I don’t know why.

I couldn’t have said it better.

November 8, 2015

Richard Feynman’s Deliberate Genius

Gleick’s Genius

I’m currently re-reading Genius, James Gleick’s celebrated biography of physicist Richard Feynman.

I was particularly drawn to the opening chapters on Feynman’s childhood in Far Rockaway, Queens. It’s tempting when encountering a brilliant mind like Feynman’s to resort to cognitive hagiography in which the future Nobel laureate entered the world already solving field equations.

But Gleick, whose research skills are an equal match for his writing ability, uncovered a more interesting origin tale…

The Math Team Factor

Arguably, the seed of Feynman’s success was his participation in the New York City public school system’s Interscholastic Algebra League.

As Gleick explains, Feynman was on his school’s math team. The team competed in meets in which the competitors raced to solve algebra problems. The important thing to understand is that these problems were designed with “special cleverness…there was always some trick, or shortcut, without which the problem just takes too long.”

Feynman became hooked on the feeling of uncovering these mathematical insights. Here’s Gleick:

“The heady rush of solving a puzzle, of feeling the mental pieces shift and fade and rearrange themselves until suddenly the slid into their grooves — the sense of power and sheer rightness — these pleasures sustain an addiction. Luxuriating in the buoyant joy of it, Feynman could sink into a trance of concentration that even his family found unnerving.”

Hungry for his next insight fix, Feynman began seeking out classic results from a variety of fields, with a particular interest in infinite summations that yielded pi or Euler’s constant (see the above image of pages from his teenage notebook).

To simply learn by rote what was already known would not provide him the hit of insight he craved, so he began working out the results on his own:

“His notebooks contained not just the principles of these subjects but also extensive tables of trigonometric functions and integrals — not copied but calculated, often by original techniques that he devised for the purpose.”

The Magician

Feynman’s colleagues, according to Gleick, understood him to be a magician: someone whose results seemed to come out of nowhere. But Feynman’s childhood training clarifies that this ability to confidently dive to the essence of a problem was a skill he pursued and sharpened starting from an age when most were still focused on backstreet stick ball.

Put another way, by the time Feynman graduated MIT — en route to the Manhattan Project, then the Cornell faculty, where his devastatingly original work on quantum mechanics would win him a Nobel Prize — he had likely spent more hours practicing the hunt for deep insight than almost anyone in his generation.

I don’t doubt that Feynman’s brain was special. But to borrow some useful terminology from David Epstein, what mattered was that this high power hardware was matched with exactly the right software, developed through years of deliberate practice, to unlock Feynman’s genius.

November 2, 2015

Spend More Time Managing Your Time

Making Time for Time

Something organized people don’t often talk about is how much time they spend organizing their time.

I think this is a shame.

The past half-decade has seen a trend in (online) time management discussions toward simplification. It’s now accepted by many that it’s enough to jot down each morning a couple “most important tasks” of the day on an index card, and if you get those done, consider your day a success.

Think about this for a moment. This belief essentially cedes the majority of your working hours over to meetings separated by bursts of non-productive inbox shuffling and web surfing.

I for one am not yet willing to give up so many hours, as doing so would significantly reduce what I’m able to accomplish in the typical week. Which brings me back to time spent organizing time…

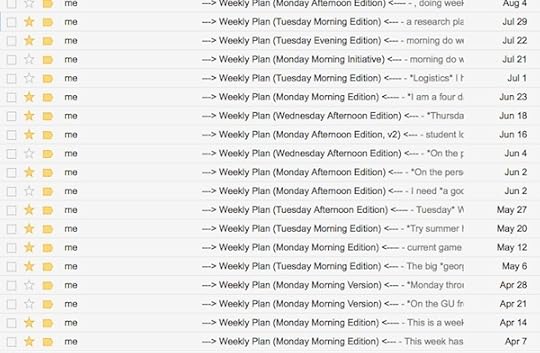

The Necessary Grind of a Good Weekly Plan

It’s not unusual for me to spend two or more hours at the beginning of each week playing with the puzzle pieces that are my commitments, big and small.

It’s hard work figuring out how to make a productive schedule come together: a goal that requires protecting long stretches of speculative deep thinking while keeping progress alive on long term projects and dispatching the small things fast enough to avoid trouble (but not so fast that the deep stretches fragment).

During today’s planning session, for example, I had to balance immediate obligations like a paper deadline this evening, with short term obligations like grading midterms, with the many medium range obligations mounting from my next book launch, to long term obligations, like the need to continue to make progress on the theorems needed for an important February deadline.

Sprinkle in a dash of appointments and a heavy dollop of tasks and it’s completely reasonable to expect that making sense of these pieces would require some serious thinking.

I’m telling you this mainly to provide another data point. It’s true that many people approach their days with flexibility, perhaps hunkering down when an immediate deadline looms, but otherwise letting their reactions to input drive the agenda. But I want to emphasize that there’s another group of us who take our time really seriously, and aren’t afraid to spend hours figuring out how best to invest it.

This level of organization is not for everyone; but everyone should know that it’s an option.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers