Cal Newport's Blog, page 45

May 4, 2015

Shipping Trumps Serendipity

The Annoyed Rhodes Scholar

To research my first book, I interviewed several Rhodes Scholars. During this process, I noticed they tended to be touchy about their press coverage.

When you win a Rhodes, not surprisingly, reporters will seek you out and write articles about you. Most of these articles follow the same shock and awe template of listing the student’s accomplishments, one after another, in an attempt to overwhelm the reader.

It was this article format that annoyed winners.

To understand why, you must first understand that most Rhodes Scholars follow a similar path: they invest a large amount of energy in doing a small number of things (usually two) extremely well (for someone their age).

Over time, as they get better and better at their core points of focus, related opportunities and accomplishments start to come along for free (see my third book for more on this phenomenon, sometimes called The Matthew Effect). It’s these freebies that ultimately extend their CV’s to a head-spinning length.

Consider, for example, the following lines from a profile of 2015 Rhodes Scholar Noam Angrist:

While at M.I.T., he did economic research for the World Bank, The White House, and on the Affordable Care Act…As a Fulbright Scholar in Botswana, Noam founded an NGO for HIV education designed to discourage intergenerational sex (“sugar daddy awareness”). Its success led him to raise the money to extend the program to 340 schools, and he now plans to launch it in four other southern African countries.

This list can appear inexplicable at first read, but a closer examination makes it clear that all of these accomplishments flow from a single deep focus: mastering the intersection between economics and program evaluation (a field being innovated at MIT, where Noam is a student).

The internships at the World Bank and White House, as well as the Fulbright Scholarship (which led to the HIV prevention program) are all side effects of Noam proving unambiguously that he was really good at this one type of academic research.

The reason Rhode Scholars get upset by volume-centric, over-hyped, shock and awe press coverage is that it obscures what they’re really proud about: doing professional quality work in a field that they respect and want respect from.

The Serendipity Hype

This experience with Rhodes Scholars came to mind recently as I pondered an idea that has become increasingly popular in the Age of Social Media: exposing yourself to many different people and opportunities is the key to serendipitously stumbling into professional breakthroughs.

I’ve long been fascinated with this concept, but the more time I spend around people actually doing things of consequence, the more I recognize its hollowness.

Here’s the reality for almost every professional pursuit: shipping things that are unambiguously valuable generates significantly more interesting and high-return opportunities than exposing yourself to lots of different people and ideas.

You probably don’t, in other words, need to invest dozens of hour a week into cultivating your social media community, or thousands of dollars a year attending feel good conferences, to stumble into the Next Big Thing in your career.

A significantly more effective path is to instead ship things that catch peoples’ attention.

Our Rhodes Scholar example from above didn’t start by trawling for interesting intern opportunities, he instead became a star economics student at MIT, and then let interesting opportunities subsequently fall into his lap.

The same pattern holds for many different fields: value attracts value.

People don’t always like hearing this advice because seeking serendipity is satisfyingly contrarian (most people don’t do it, so you can feel special if you do), while at the same time saving you from the difficulty of having to compete (and fail) in clearly defined arenas.

But a decade spent researching and writing about elite accomplishment (while attempting to pursue it myself in my academic career) has taught me that: (1) there aren’t any hacks that will save you from the necessity of stepping into a ring and winning over other people who desperately want to do the same; and (2) this first step is really, really hard.

This isn’t a lesson that I perfectly embody, but is instead one that I have to keep reminding myself to pursue. If you want a breakthrough, forget serendipity and focusing on shipping.

April 24, 2015

The Original Four Hour Workweek

The Four Hour Consensus

In 2007, Tim Ferriss published a hit book that suggested “work,” in the traditional money-making sense of the term, could and should be reduced to as little as four hours per week — freeing time for more fulfilling pursuits.

In 2007, Tim Ferriss published a hit book that suggested “work,” in the traditional money-making sense of the term, could and should be reduced to as little as four hours per week — freeing time for more fulfilling pursuits.

Seventy-five years earlier, the British philosopher Bertrand Russell, in an essay titled In Praise of Idleness, suggested this same number of working hours as a worthy goal, explaining…

In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day, every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving…Young writers will not be obliged to draw attention to themselves by sensational pot-boilers…Men who, in their professional work, have become interested in some phase of economics or government, will be able to develop their ideas…

Russell and Ferriss propose wildly different paths to this goal: while the former believed a radically reduced workweek requires socialism to realize, Ferriss argues that the productivity tools of the Internet Age suffice.

But both writers hit on a deeper idea that has remained as intriguing today as in the 1930s: the notion that industry (what we might now call “busyness”) is intrinsically virtuous is suspect. It’s worth instead working backwards from a more general confrontation with the question of what matters and deciding how best to act on the answers.

I don’t have a specific point of view here (I know Russell mainly from his work on mathematical philosophy), I just thought the coincidence was cool, and the ideas interesting…

######

On an unrelated note, my friends over at the exceptional 80,000 Hours organization have recently released a (free) career guide that is among one of the most thoughtful and grounded I’ve seen. If you read SO GOOD, you’ll probably appreciate their technical take on cultivating (not finding) passion.

April 19, 2015

It’s Not Your Job to Figure Out Why an Apple Watch Might Be Useful

The Watch to Watch

A couple weeks ago, the New York Times reviewed the Apple Watch. A paragraph early in the article caught my attention:

First there was a day to learn the device’s initially complex user interface. Then another to determine how it could best fit it into my life. And still one more to figure out exactly what Apple’s first major new product in five years is trying to do — and, crucially, what it isn’t.

It’s worth taking a moment to recognize what’s strange here. If it takes three days to figure out why something might be useful to you, then you probably don’t need it!

In any other market, a product without a clear use case would be impossible to sell. But in the cultural distortion field of Silicon Valley, this is the new normal. They provide the hot new thing, and it’s up to you to figure out why you need it.

Start With Why, Not What

The reason this state of affairs worries me is because once you start letting other people tell you how to invest your limited time and attention, you’re almost certainly going to stray from the things you find most important.

Here, for example, is the reporter from the above article explaining his experience with the Apple Watch (once, that is, he figured out how to work it): “[it] became something like a natural extension of my body, a direct link, in a way that I’ve never felt before, from the digital world to my brain.”

For anyone trying to build (or write, or code, or paint, or plan) something of consequence, this is, to steal a line from George Packer, a truly frightening vision of the future!

But when you work backwards from what’s hot, instead of what you need, this is the type of behavior you stumble into.

The alternative here is simple: Decide what matters to you; seek out the tools that most directly and obviously help you accomplish these things; then get down to work.

Life’s too short to waste three days trying to figure out whether some shiny new gizmo might be useful.

April 11, 2015

Deep Habits: Listen to Baseball on the Radio

Distracted in the Dugout

Last week, the Washington Post featured a front page story about the declining number of kids who play organized baseball. There are various reasons for this decline, but the story emphasized the sport’s lack of action.

Here’s an articulate 15-year old, as quoted in the article, explaining his reasons for quitting baseball:

Baseball is a bunch of thinking, and I live a different lifestyle than baseball. In basketball and football, you live in the moment. You got to be quick. Everything I do, I do with urgency.

This teenager is right. Baseball, undoubtedly, is a slow sport: even more so for spectators than the players.

But while this might be bad news for those hoping to attract the allegiance of the iPhone generation, I’ve found it to be quite useful in my own quest to sharpen my deep work skills.

Deep Relaxation

In particular, I try to listen to at least one baseball game per week on the radio (we don’t have cable, and I can’t stream local coverage, so there’s no other way for me to legally catch the games).

When listening, I maintain a strict “no technology” rule — no phones, no iPads, no other source of electronic distraction (I do allow myself to read during commercial breaks).

My experience is that the slowness of the games, combined with the lack of visual stimuli, can be, at first, excruciating.

If I stick with it, however, my mind eventually downshifts — quieting the noisy neuronal clamoring for easy entertainment, and leaving instead an unencumbered attention of a type that I often seek in my work.

Listening to a ballgame, in other words, becomes excellent training for reaching and maintaining the deep mental states that produces things that matter.

I’m not suggesting that everyone become baseball fans. I am suggesting, however, that if you take deep work seriously, it’s worth having some rituals outside your professional life that help you practice the states of mind it requires.

(Photo by Garry Wilmore)

April 5, 2015

What Steve Jobs Meant When He Said “Follow Your Heart”

What Steve Said

I opened my last book with Steve Jobs’s 2005 commencement address at Standford University. Toward the end of the speech, I noted, Jobs said:

And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.

Many people interpreted this suggestion simplistically, assuming that Jobs was telling them to follow their passion and everything would work out.

I argued in my book that this interpretation conflicted with Jobs’s own story. During the period leading up to Apple’s founding, there was no indication that Jobs felt any particular passion for technology entrepreneurship.

His company was, in many ways, a happy accident that evolved into a calling.

What, then, explains the mismatch between what Steve Jobs did and what Steve Jobs said?

Fortunately, we gain new insight into this question from Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli’s excellent new biography, Becoming Steve Jobs. In this book, the authors (one of whom had a long term personal relationship with Jobs) devote a full chapter to dissecting the Stanford address, taking specific aim at his “follow your heart” line.

Not only do Schlender and Tetzeli provide needed nuance to Jobs’s advice, but they also end up providing one of the more sophisticated and useful interpretations of professional passion that I’ve heard…

Beyond “Shuttered Confidence”

The authors begin by acknowledging Jobs’s word choice skirts the border of cheesy:

Without the proof of Apple’s success, these words from the speech’s final chapter could be misread as the kind of shallow cheer-leading intoned by high school valedictorians.

But they then note that Jobs’s success buys him the benefit of the doubt:

…but what gives [the words] strength and power is that they come from someone who has proved their value in a corporate setting.

So what did Jobs’s mean? In a nice turn of phrase, the authors note that Jobs learned how to “modulate the potential solipsism of ‘follow your heart’“, elaborating:

Early in [Jobs’s] career, intuition had meant a shuttered confidence in the inventions of his own brain. There was a stubborn refusal to consider the thoughts of others. By 2005 intuition had come to mean a sense of what to do that grew out of entertaining a world possibilities. He was confident enough now to listen to his team as well as his own thoughts and to acknowledge the nature of the world around him.

In other words, Jobs was not suggesting that we all have a true calling that must be unearthed before you can begin your career.

He was instead arguing that as your professional expertise and power grow, you must resist the urge to be washed along in the flow of convention. It’s then that it becomes important to integrate your maturing intuition — in full cooperation with your expert knowledge of your field and the realities of the world around you — to steer toward something that might leave a dent in the universe.

This is likely why, in another part of the speech, Jobs describes meaningful work by noting: “like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on.”

#####

The book quotes come around the 32 minute mark in Chapter 14 of the Audible.com audio version. All emphases are my own.

March 31, 2015

From Obscurity to Genius: The Deep Life of Yitang Zhang

Bound Gaps Solved

Last year, Yitang (Tom) Zhang published a paper in the Annals of Mathematics titled “Bounded Gaps Between Primes.” The abstract for the paper is simple enough for a non-mathematician to understand. It states that there are infinitely many pairs of consecutive prime numbers that are no more than 70,000,000 apart.

Don’t let the simplicity of the claim fool you: people have being trying to prove something like this for over 150 years.

At the time when Zhang submitted his result he held a “tenuous” temporary position in the mathematics department at the University of New Hampshire. As reported in Alec Wilkinson’s elegant New Yorker profile, before a friend set Zhang up with the New Hampshire position, he bounced around odd jobs, including a stint keeping the books at a Subway franchise.

Soon after his result was published, everything changed. His employer (wisely and with haste) made him a professor. He was invited to spend six months at the Institute for Advanced Study and accepted lecture invitations across the country. That same year, he was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant.

What caught my attention about Zhang, however, was not the elegance of his result (which, as a lowly applied mathematician, I cannot come close to understanding) but the elegance of his work habits.

A Deep Life

Zhang began to work on bound gaps (as it’s often called) in 2010. He didn’t find his “door” into the problem until the summer of 2012, when, standing in a friend’s backyard in Colorado, smoking a cigarette and watching for deer, he finally saw a way to penetrate its knotty interior.

In that two year period, between when Zhang started on the problem and had his first breakthrough, he spent much of his waking life simply thinking. Here’s Wilkinson’s description of Zhang’s “method”:

A few years ago, Zhang sold his car, because he didn’t really use it. He rents an apartment about four miles from campus and rides to and from his office with students on a school shuttle. He says that he sits on the bus and thinks. Seven days a week, he arrives at his office around eight or nine and stays until six or seven. The longest he has taken off from thinking is two weeks. Sometimes he wakes in the morning thinking of a math problem he had been considering when he fell asleep. Outside his office is a long corridor that he likes to walk up and down. Otherwise, he walks outside.

I don’t have a piece of pragmatic advice to extract from this story. Most people cannot spend two years thinking about the same thing for ten hours a day, and it wouldn’t help their professional life much if they did.

But I think Zhang’s story highlights the beauty and potential of a mind left to do nothing but think without interruption at its highest capacity…

(Photo from the John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

March 26, 2015

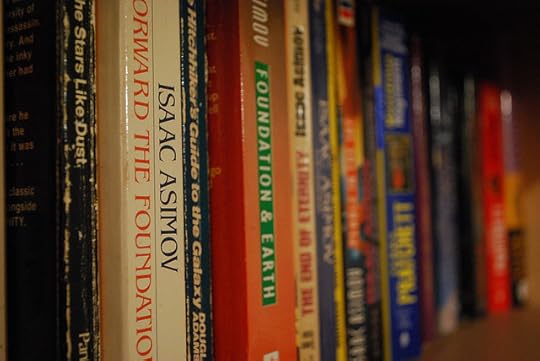

Isaac Asimov’s Advice for Being Creative (Hint: Don’t Brainstorm)

Asimov’s Lost Essay

In the late 1950’s, Arthur Obermayer worked for Allied Research Associates, a cold war-era science lab. During this period, his employer received a grant from the Advanced Research Projects Agency to “elicit the most creative approaches possible for a ballistic missile defense system.”

Obermayer was a longtime friend of the famed science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. Figuring that Asimov might know a thing or two about creativity, he brought him into the project.

The result was an essay, penned by Asimov, on the topic of creative breakthroughs. Oberymayer recently brought this essay to the attention of the MIT Technology Review magazine, which reprinted it in full.

The piece contains several original notions, but what caught my attention was its take on where creative ideas come from.

The Creativity of One

Every since ad man Alex Osborn introduced the brainstorming technique in the early 1940’s, creativity has been sold as a collaborative process. This is a big part of the reason, for example, why Facebook is creating the world’s largest open office in its new headquarters — people need to serendipitously bounce ideas off of each other to stumble onto breakthroughs.

Asimov disagrees:

My feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required. The creative person is, in any case, continually working at it. His mind is shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it.

To have people sit in a room and jot ideas on butcher paper, or to chat idly at their open office work tables, in other words, is not likely to generate deep insight.

Indeed, such collaboration can even hurt this goal:

The presence of others can only inhibit this process, since creation is embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display.

This doesn’t mean, however, that bringing creative people together is worthless. As Asimov elaborates, group meetings, if kept small (he estimates five people as an ideal size), do have a use.

Just not the one we’re used to hearing.

The goal for creative meetings is not to come up with new ideas, he argues, but instead to transfer the raw material for these ideas between participants. As Asimov explains: “No two people exactly duplicate each others’ mental stores of items.”

The goal of collaboration, in other words, is to quickly increase the store of material that the creative can then work with once returned to his or her isolated cogitation.

As someone who makes a living on creative insights (how else to describe proof solving), I’m sympathetic to Asimov’s take. While group activities like brainstorming might be useful for lightweight projects, like coming up with a new slogan for an advertisement, if you’re instead trying to solve an unsolved proof, or, more pressingly, improve ballistic missile defense, there’s no way to avoid learning hard things and then thinking hard about what you learned, hoping to tease out a new connection.

This is fundamentally a deep process — one that no amount of brainstorming sessions or distracting open office spaces can short circuit.

(Photo by Firas Wehbe)

March 16, 2015

Deep Habits: Think Hard Outside The Office

Deep Work After Hours

One lesson I learned after becoming a professor is that producing intellectual insights at a professional pace requires deep thinking beyond the confines of the normal workday. Though I’m quite good at protecting and prioritizing deep work against the encroachment of the shallow, the depth I can fit into my regular schedule is not sufficient.

My strategy is to maintain, at all times, a single, clear problem primed and ready for cogitation. I then set aside specific times for this deep thinking in my schedule outside work. I use many (though not all) of my commutes for this purpose. I also leverage long weekend dog walks and the mental lull that accompanies time-consuming house work.

(People sometimes ask what I do with the free time I preserve by not using any social media or web surfing. This is a large part of my answer.)

Quality Over Quantity

This habits adds an additional half dozen hours (on average) of deep thinking to my week. This might not seem like a lot, but more important than the number of hours gained is their quality.

Because this deep thinking is freed from the context of an otherwise draining workday, I can often muster more mental energy than, say, at 3:00 on a Thursday afternoon.

Another advantage is that these blocks are short. This allows me to make many fresh attacks on a problem, which is generally more likely to generate a breakthrough than combining that time into one long slog.

Caveat Emptor

A word of warning concerning this approach is that there is significant difference between having a primed undecidable task to work on after hours, and just letting your normal, shallow obligations bleed into your evenings and weekends.

The former can be invigorating while the latter is draining and often devolves into stressful workaholism.

Put another way, I think fixed-schedule productivity and work shutdown routines (and all the benefits they bestow) are fully compatible with this habit — at least, in my experience.

This being said, this habit is not always innocuous. It’s easy sometimes for it to get out of hand.

For example, sometimes, when I get close to a solution, I get a little obsessive in my thinking and it bleeds into whatever else the family is doing: at which point it becomes noticeable (and annoying) to those around me. If I spend more than a day or two in this state, I will burn out — which isn’t pleasant.

But usually, this extracurricular contemplation remains well-contained.

Bottom Line

To conclude, I’m not sure if this approach generalizes much beyond the weird world I live in where people pay me to prove things (though I suspect it does). But at the very least, it provides some insight into the often grinding (and occasionally exhilarating) pursuit of a career in the world of professional thinking.

March 13, 2015

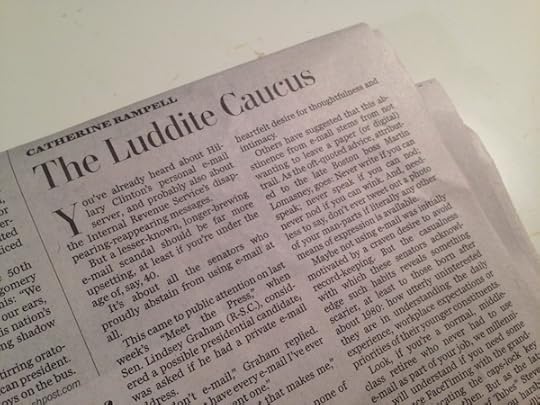

Many Senators Don’t Use E-mail. This Shouldn’t Bother You.

Redeeming The Luddite Caucus

Earlier this morning I was reading The Washington Post while watching the sun rise (I have two young kids at home: I find quiet where I can). A column by Catherine Rampell, titled The Luddite Caucus, caught my attention.

As I began to read, my interest transformed into concern.

In the wake of the recent Hillary Clinton e-mail story, many reporters, it turns out, have been asking other politicians about their digital habits. After reviewing these articles, Rampell reports that there are a surprising number of United States senators who rarely use e-mail — a list that includes: Lindsey Graham, John McCain, Pat Roberts, Richard Shelby, Orrin Hatch, and Chuck Schumer.

Rampell is shocked that so many senators “proudly abstain” from e-mail.

She accuses them of being “utterly uninterested” in “understanding the daily experience, workplace expectations or priorities of their younger constituents.”

She describes the senators as displaying “mindboggling levels of societal incuriosity,” to the point that this behavior should be considered “political malpractice.”

She concludes by asserting that contemporary technology use is a “necessary” condition for understanding “good tech policy”, rendering these senators unqualified to address laws that affect technology, privacy, labor, global competitiveness, and, for some reason, immigration.

As you might have guessed: I don’t buy this argument.

To require a senator’s personal involvement before he or she can be either “interested” or “qualified” to address a sector of our economy is an idea that quickly succumbs to reductio ad absurdum.

Only a quarter of senators served in the military. Are the rest uninterested in our armed forces?

Almost no senators are farmers. Are the rest unqualified to vote on agricultural subsidies?

And so on.

But quibbles with Rampell’s line of reasoning is not my main concern. I’m more worried by the fact that many readers will, without much deliberation, agree with her.

This idea that you must embrace everything Internet, or be labeled incurious, out of touch, or even Ludditic has become ubiquitous.

This sentiment is harmful, and probably even damaging to our country’s economic competitiveness.

This conclusion follows from an obvious point worth repeated reiteration: not all digital tools are useful to all people. To force everyone to use everything, or be deemed out of touch, will make many people worse at what they do.

Senators, for example, don’t need e-mail. Their staffs do, but the senators don’t. To be a member of the world’s greatest deliberative body means that you’re better off spending your time actually deliberating than checking your BlackBerry.

Do you really think John McCain or Chuck Schumer would somehow be better at their job if they spent more time cleaning their inbox?

My argument on this point has been consistent over the years: we need to take Internet technologies off a pedestal. They’re simply tools, like a wheat combine or an architect’s t-square.

For some people they’re indispensable. For others they don’t matter.

It’s more important to turn our attention back to the metric that does matter universally: Are you creating value in the world.

This is what should concern us. Not whether or not I can easily find you on Gmail.

March 9, 2015

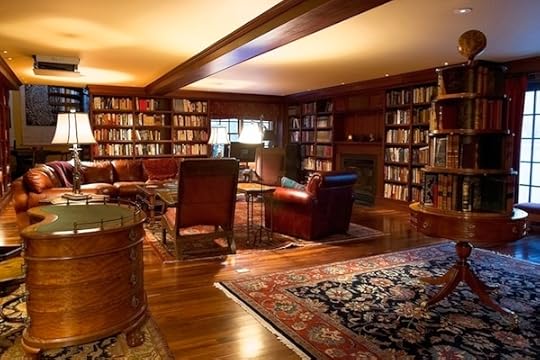

You Are Where You Work: More Examples of Fantastically Deep Working Spaces

A couple weeks ago, I wrote a post about three writers who custom-built work spaces to help them go deeper with their craft. In response, many of you sent more examples of fantastic deep work spaces. I thought I’d share a few of my favorites, as the more I dive into this idea of “method working,” the more appealing it becomes…

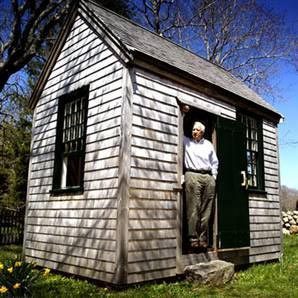

David McCullough’s Cabin

(Image from Reason and Reflection.)

Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner David McCullough, it turns out, writes his biographies in a eight-by-twelve cabin on the property of his Martha’s Vineyard farm. He calls it his “World Headquarters.” Supposedly, he once quipped, “nothing good was ever written in a large room.”

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Lincoln Library

(Image from the Wall Street Journal.)

Not to be outdone, another Pulitzer-winning historian, Doris Kearns Goodwin, wrote much of Team of Rivals at her Concord, Massachusetts home, in a library holding over 1000 books on the former president.

Hans Zimmer’s Gothic Studio

(Image by Trey Ratcliff.)

The movie composer Hans Zimmer built a Gothic/Victorian studio that perfectly matches his style of brooding crescendo.

Mahler’s Hut

(Image from Alex Ross.)

And the composer Gustav Mahler did much of his great work in a collection of three huts he built to escape the city noise. The one pictured above, facing the water, is my personal favorite.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers