Cal Newport's Blog, page 49

September 10, 2014

A Personal Appeal

I don’t often allow my non-professional life to seep into this blog, so this post represents a rare violation of this habit…

This Saturday, I’m participating in a fund raising event called the Race for Every Child. My team in this event is raising money for a foundation started by our friends Gabi and John Conecker.

This Saturday, I’m participating in a fund raising event called the Race for Every Child. My team in this event is raising money for a foundation started by our friends Gabi and John Conecker.

The Conecker’s son, Ellliott, was born almost two years ago (the same time as our son, Max) afflicted with a devastating genetic disorder virtually unknown to science. They soon discovered that families all over the country are going through something similar each year (c.f., this New Yorker article).

Their foundation helps raise awareness and more importantly fund research to better understand and treat these disorders. (The foundation directly supports the research efforts of a world class neurogeneticist at Children’s National Medical Center who is making real progress into understanding the impact of these mutations.)

Anyway, if this type of cause resonates, please consider donating something to the effort sometime between now and Saturday. You can learn more about the foundation and donate here.

If you do donate, please send me an e-mail at personal@calnewport.com so I can thank you personally.

If this type of cause doesn’t resonate, please disregard. We’ll return shortly to our regularly scheduled programming.

September 8, 2014

Deep Habits: When the Going Gets Tough, Build a Temporary Plan

The Temporary Plan

As I’ve revealed in recent blog posts, there are two types of planning I swear by. The first is daily planning, in which I give every hour of my day a job. The second is weekly planning, where I figure out how to extract the most work from each week.

These are the only two levels of planning that I consistently deploy.

But there’s a third level that I turn to maybe two or three times a year, during periods where multiple deadlines crowd into the same short period. I call it (somewhat blandly, I now realize) a temporary plan.

A temporary plan is a plan that operates on the scale of weeks. That is, a single plan of this type might describe my objectives for a collection of many weeks.

When a lot of deadlines loom, I find it’s necessary to retreat to this scale to ensure things get started early enough that I can coast up to the due dates with the needed pieces falling easily into place. If I instead planned each week as it arose, there is too much risk that I would find myself suddenly facing a lot of uncompleted work all due in the next few days!

Logistically speaking, I typically e-mail myself the temporary plan and leave it in my inbox. My general rule is that if a temporary plan is in my inbox while I’m building my weekly plan, I read it first to make sure my weekly plan aligns with the bigger picture vision.

A Temporary Plan Case Study

To help make this strategy more concrete, let’s consider a temporary plan I developed last spring to make sure that the papers I was working on for a May deadline would come together in time while I still made progress on some other efforts that also had looming deadlines. I replicated this plan below. (I added my commentary in square brackets):

DISC abstract registration is May 9th. Final submission is May 14th. Here is my plan until then…

[Note from Cal: "DISC" is the name of the conference I wanted to submit my papers to. (This is a good time to remind the reader that in computer science most publication activity happens at competitive peer-review conferences with submission deadlines.) I put the deadlines at the top of this plan so I wouldn't forget where I was relative to them.]

April 21 – April 27

Finish full technical draft of Radio Networks (including related work); double check relevant details with .

Big push on full technical draft of Unreliable Links paper.

Talk to about SDN paper.

[Note from Cal: "Radio Networks" and "Unreliable Links" were two papers I was working on for DISC. The "SDN" paper was not for DISC, but I wanted to keep it active.]

April 28 to May 4

Finish full technical draft of Unreliable Links paper.

Resubmit Wireless Survey as soon as that is done

Make PODC CR plan

[Note from Cal: These last two elements have nothing to do with DISC. But I needed to address them.]

May 5 to May 11

Go back and forth between polishing DISC papers and PODC CR work

[Note from Cal: "PODC CR" refers to the fact that I had to submit camera-ready versions of papers for another conference called PODC. It was bad luck that this deadline fell so near the DISC deadline. Most people would probably just leave the PODC CR work until the last minute, but my fixed schedule productivity commitment requires me to be more thoughtful about such efforts to avoid late nights.]

May 12 to Deadline on May 14th

Final polishes.

This is the place to really . Also a time to add any

Notice, the plan is informal and concise. I just include a few sentences for each week, but a few sentences was enough to guide me through that month of work in an efficient and effective manner. I ended up making it to the relevant deadlines above without spending a single late night working and ended up with a nice result for these carefully scheduled efforts.

A Tool of Last Resort

I call this type of plan “temporary” because I want to emphasize that they’re short-lived and used only when the circumstances absolutely require them. To plan at this level regularly would be, in my opinion, overkill.

But when the going gets tough, I’ve found this bigger picture view to be an immense advantage.

P.S. I’ve been calling these “temporary plans” for years, but I do recognize that this is a terrible name. Let me know in the comments if you have a better term for them.

#####

My friend Chris Guillebeau’s new big deal book, The Happiness of Pursuit, comes out today. I’ve known Chris since the beginning of his blogging days and have always been impressed by his thinking. This book is no exception. His main thesis is that the pursuit of grand goals generates great satisfaction somewhat independent of the content of the goals. This is an idea I toyed with in Rule 4 of SO GOOD, but Chris takes it somewhere more concrete and compelling. He also lived it with his personal quest to visit every country in the world. Check it out…

September 4, 2014

John Cage on the Necessity of Boredom

Words of Wisdom

A reader recently pointed my attention to the following quote from the composer and artist John Cage:

“If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.”

She thought I would like it and she was right. Cage captures something fundamental about deep work on important things: there’s a stage — sometimes a long stage — that’s tedious.

The good news, of course, is that over time, tedium gives way to glimpses of potential that then grow into something downright eudaimonic.

Once you recognize this reality, your potential to do things that matter is unleashed.

August 29, 2014

Deep Habits: Pursue Clarity Before Pursuing Results

Shallow September

I track my deep work hours using a weekly tally, so I have a good sense of how my commitment to depth varies over time. A trend I’ve noticed is that my deep work rate hits a low point around this time of year.

The obvious explanation is that the start of the fall semester adds extra time constraints. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. My deep work tends to increase as the fall continues, even though my teaching commitments also increase during this period (i.e., once there are problem sets and exams to grade).

In thinking about this mystery I’ve begun to better understand a crucial but often ignored aspect of working deeply on important things: the necessity of clarity.

My Research Cycle

In my life as a distributed algorithm researcher, I experience a rapid-fire set of important research deadlines that begin in the late winter and end mid summer. If all goes well, this period clears out my research larder, leaving me, by mid-July, ready to start a new research cycle.

This reality explains why my deep work dips around this period: it’s not clear what I should be working on.

When I have a well-developed problem, and I have a sense of what the solution should look like, and I can feel that my attacks are getting closer to the core: it’s easy to obsessively accumulate hour after hour of deep thinking.

By contrast, when I have only a hazy idea for a type of problem that might be interesting, but am not sure exactly how to define it or if it’s something I can solve: it’s easy to push aside deep hours for other more concrete concerns.

In the fall, in other words, I’m rich in haziness and poor in clarity.

There’s nothing wrong with this. All projects require this haziness stage. High output rates, therefore, will force you into this stage frequently.

Prioritizing Clarity

The conclusion I’ve been developing is that I need to think more systematically about minimizing the time to get from haziness to the level of clarity that accelerates depth. In more detail, when in a period of haziness, I’m becoming increasingly comfortable with the idea that much of the time that I might usually spend on traditional deep work (concentrating without distraction on a well-defined problem) will instead be spent trying to clarify hazy ideas to a point where such depth is possible.

In my particular line of work, the following activities seem to help:

Agree to give a talk on the topic.

Go visit (or invite to visit) a collaborator to bounce around the idea.

Setup a (bounded) series of meetings of phone calls to see if the idea can be kneaded into something pliable.

Read, read, read related work and capture the notes in an annotated bib (a tip that has arguably doubled my research productivity)

And finally, once ready, spend a half day or so trying to write up a problem document that captures a clear description of the problem, a collection of simple results, and a list of some next results that seems promising and tractable (this is like a business plan for a research problem, and usually something I like to develop before committing to long term time investment).

The specifics of these activities will differ depending on your job. But the big idea here is that by dedicating some deep work time to seeking project clarity (when projects are hazy), you’ll end up with more quality results in the long run.

August 24, 2014

The Nuanced Road to Passion: A Career Case Study

The Insult of Simplicity

There are many reasons why I don’t like the advice to “follow your passion.”

One reason I haven’t mentioned much recently is that I find its premise insultingly simplistic.

It would be nice if we were all born with a clear preexisting passion.

It would also be nice if simply matching your job to a topic you liked was all it took to generate a meaningful career.

But reality is more nuanced (as we should expect, given the rareness and desirability of the goal being pursued here).

In an effort to be more positive than negative, however, I thought it might be useful to provide a brief case study that sketches a more realistic image of how people end up with work that matters.

This case study comes from a reader whom I’ll call Peter…

Peter’s Tale

After graduating college, Peter, like many recent graduates, had no clear preexisting passion to guide him. So, like many recent graduates, he did something expected: he applied to law school.

At law school, Peter began to build useful skills. Among other things, he learned to write precisely, think analytically, and more specifically, to unwind legal statutes.

During his summers he interned at various organization. One of these internships was with a large NGO. He learned that the work of this organization (it’s a non-profit you’ve heard of before) resonated with him. Of equal importance, he learned that one of the divisions in this organization had need of lawyers.

So Peter worked hard during the internship and the remainder of law school (he claimed that his now battered copy of Straight-A helped him through this period).

This performance earned him a job offer from the NGO. He’s excited for the position which he is just about to begin.

It’s too early to tell whether this particular career direction will continue to blossom into a true passion for Peter, but there’s a good chance it will (I’ve heard this same opening act many times before).

What strikes me about this narrative is that it complicates the simple tropes advanced by the Passionistas.

Peter, for example, described his journey as follows:

“It really was a matter of following the path where I could build on my existing skills and had the potential to move towards some kind of mastery.”

He then added:

“When others ask for advice, they seem to want to hear the narrative about how I followed my passion, but that would be an enormous oversimplification.”

When it comes to the important task of build a meaningful career, I think we need to hear more from the Peters of the world, and less oversimplified cheer-leading.

###

Administrative Note: I did a talk for Jenny Blake’s Speak Like a Pro virtual conference. If you’re interested in public speaking you might find the conference interesting. I believe it begins today (Monday). Check it out…

(Photo by The Other Dan)

August 19, 2014

Deep Habits: How a Big City Lawyer Uses Weekly Planning to Accomplish More in 45 Hours Than Most Could Accomplish in 100

A Weekly Plan Case Study

Last week I wrote a post about my habit of planning out my whole week in advance. I provided some example plans from my own life, but many of you were interested in how this technique applies to other types of work.

Fortunately, I recently received the following note from a lawyer whom I’ll call John:

I tried writing out my week last week for the first time using [a method from your blog post]. When I reviewed my week on Friday afternoon, I was surprised at how much more I accomplished compared to my usual method of scheduling time to complete tasks in Outlook. Thanks for sharing this method.

Naturally, I asked John if he’d allow me to share his plan with you. He agreed. Here it is (properly anonymized, of course):

Monday

Work on [contract draft under urgent deadline] for 120 minutes before doing anything. Ship by 11am. Then, do weekly planning and finish before lunch.

After lunch, talk to [founder of startup I advise], meditate, then draft [company name] distribution agreements for a 120 minute block. Ship both by 4pm.

Take a short break, then edit [writing project] posts for tomorrow and Wednesday by 6pm. Finish with 30 minutes of small tasks and follow ups.

Leave by 6:30.

Tuesday

In the morning, work on [big-picture strategic project] for morning block. By 11:30am, take a short break to make a few calls (landscaper, etc).

After lunch, meditate, talk to [potential collaborator], then work on open agreements for a 120 minute block. Ship both by 3:30pm.

Take a short break, then spend 90 minutes clearing any sales-side projects. When clear, work on follow ups and batched tasks, and confirm meetings for tomorrow.

Leave by 6:30.

Wednesday

Take the 8am train into the city. On the train, work on batched tasks and copy review. Meet with [mentor] at 9:30, then head to Dumbo for lunch. Be sure to have small tasks to complete on the subway.

After lunch, meeting with [business colleague] downtown. In between meetings and heading back to Penn to come home, work on sales agency issues for marketing team.

Thursday

Meet with [global head of the business I work with] at 9am. After meeting, do immediate follow up items, then write [writing project] before lunch.

After lunch, meditate, then work on [one big picture project] for 120 minutes. Complete by 4pm.

Take a quick break, then do calls for [sales issue]. Finish by 6:30.

Friday

Clear low hanging fruit [Note: this is how I refer to the short marketing review and non-urgent "quick questions" in-house lawyers get constantly - I try to batch these to Friday mornings]. Inbox should be empty by the end of this block.

Write [writing project] for Monday. Send to [writing partner] before lunch.

Have lunch, meditate, then take 120 minutes on the most important thing left to do this week. Clear emails.

Leave by 5pm.

Dissecting John’s Plan

In analyzing why the weekly plan method worked well for his busy schedule, John mentioned the following:

By writing out the narrative of the week as a whole, I can consider everything that I want to accomplish, how much time I actually have and where I will be at various points in the week…Most importantly, I have to think about what I can realistically get done in every chunk of time through the week — it becomes clear immediately whether my expectations are realistic and forces me to say no to things that I might otherwise think I can squeeze in somewhere.

This is a beautiful summary of what makes weekly planning so effective. Contrary to what philosophies like Getting Things Done preach, knowledge work does not reduce to the mindless cranking of widgets (a state in which it’s enough to simply keep asking, “what task comes next?”).

By instead crafting a narrative for the full week you’re much more likely to keep your attention focused on what matters and get the right work done with time to spare.

John is a productive big city lawyer who manages to tackle a major writing project on the side (cryptically referenced in the above plan) while still ending work by 6:30 pm or earlier. If weekly planning enables this for John, imagine what it might enable for you.

August 14, 2014

On the Hardness of Important Things

Einstein’s Strain

Earlier today, I was browsing Maria Popova’s Brain Pickings blog and stumbled across a letter that Albert Einstein wrote to his son Hans Albert in the fall of 1915.

This date, of course, is important in the lifetime of Albert Einstein, as this was right after he finished writing one of the masterpieces of modern science: his general theory of relativity.

(To paraphrase my astronomy teacher at Dartmouth: “most scientific breakthroughs are expected, many different people are closing in on the same idea, but general relativity, this came out of nowhere, it was magic.”)

One quote, in particular, caught my attention:

“What I have achieved through such a lot of strenuous work shall not only be there for strangers but especially for my own boys. These days I have completed one of the most beautiful works of my life, when you are bigger, I will tell you about it.” [emphasis mine]

Einstein’s reference to “a lot of strenuous work” emphasizes an important reality: accomplishing important things is really, really hard. (He’s guilty of understatement here. The strain of proving the theory turned his hair white and nearly shattered his family and his health.)

It’s easy to play lip service to this idea, and many of us do, but what frustrates me is that there’s so little in the advice literature that directly addresses the nuances of this requirement.

It’s not obvious how to prepare yourself for really hard things. What should you expect? What changes are necessary to the way you approach your life and work? How do you know when to persist? (I mention these questions not because I have great answers, but because I want better ones.)

Seth Godin’s book, The Dip, is an important initial meditation on this subject, and one I found immensely useful, but I’m not aware of many other books that tackle this topic. This is a shame given its importance to the goal of making a mark.

August 8, 2014

Deep Habits: Plan Your Week in Advance

A Planning Habit

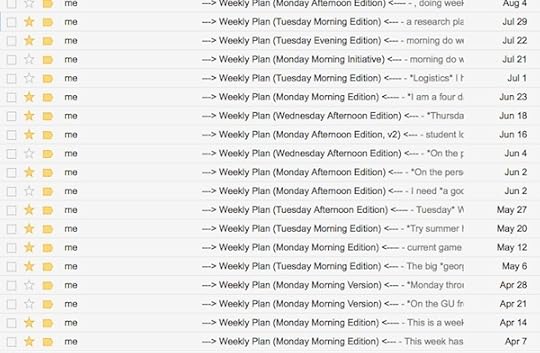

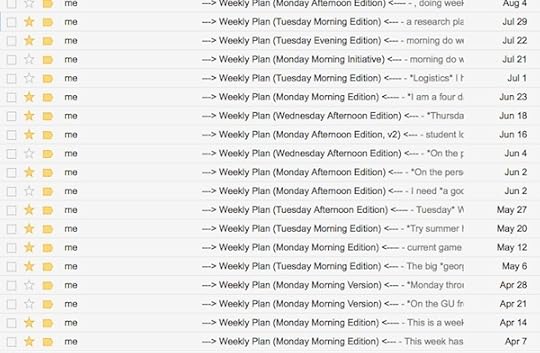

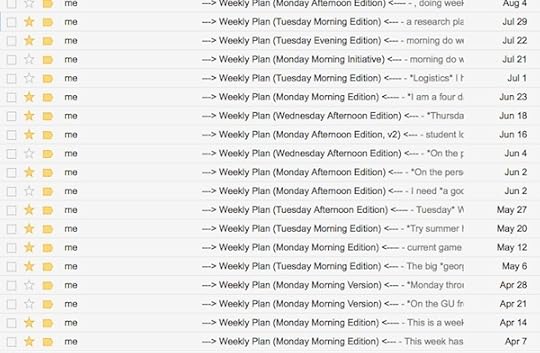

On Monday mornings I plan the upcoming work week. I capture this plan in an e-mail and send it to myself so that I will be sure to see it and have access to it daily. (See the snapshot above of some recent plans in my inbox.)

This planning can take a long time; almost always longer than an hour. But the return on investment is phenomenal. To visualize your whole week at once allows you to spread out, batch, and prioritize work in a manner that significantly increases what you accomplish and goes a long way toward eliminating work pile-ups and late nights (the latter being crucial if you practice fixed-schedule productivity).

There is no best format for creating a weekly plan. In fact, I’ve found it’s crucial to embrace flexibility. The style or format of your plan should match the challenges of the specific week ahead. (Indeed, attempting to force some format to your plan can reduce the probability you maintain the habit.)

To illustrate this point, I will show you two recent weekly plans I used (with the content scrubbed where needed for privacy reasons).

Weekly Plan #1

Monday

After weekly planning do a focused task block to get out ahead of the small things on my lists for the week. Be sure in this block to finish

Prepare a lecture for

End the work day with a 1 – 2 hour writing block.

Tuesday

Today is a research day: head in the office right away to dig into .

End day with 1.5 hours in , where the first hour is writing and the last thirty minutes is a batched attack on tasks.

Wednesday

I have a training seminar to attend in the morning and a meeting with my student in the later afternoon. Between these two events focus on prepping another lecture.

Depending on the length of my afternoon meeting, I may be able fit in a task block before coming home.

Thursday

First thing in the morning do budget and take care of . The goal is to finish before

After the doctor’s appointment find a quiet place to work deeply on .

End day somewhat early for

Friday

Write. Deep work on research until mental burn out. Shutdown for weekend. Finish

The above weekly plan represents the most common format I use: sketching my goals for each day of the week. Notice, I’m not simply listing things I want to get done each day, but instead am trying to match work to the time that actually seems available on those days. A big part of the weekly planning process is working backwards from your calendar to fill in the open time effectively. Fortunately, because this plan is for a summer week, I had lots of open time to work with.

Now consider another plan that I used a few weeks after the above example…

Weekly Plan #2

Research

Carve out three hours of deep work every day for the below research tasks. This is the core of each day’s schedule.

This week is do or die for getting to a final result for

During downtime on this project (while waiting for responses from co-authors), see if I can push through

Dedicate one day’s deep work for finishing

Georgetown Teaching/Misc

Each day, outside of the deep work hours assigned above, make progress on the below non-deep tasks.

Once my new textbook arrives, I need to decide on my syllabus for and post online.

The following small tasks are time sensitive this week: (1) pick up new parking pass; (2) send back visa letter for ; (3) respond to recent questions.

Writing

Use the morning block and commute to plan and gather the sources I need to start writing next week.

Over weekend, write a blog post where I

This plan adopts a different format. Because this was a summer week with no major appointments, meetings, or other scheduled obligations to break up my days (so rare, yet so wonderful), I could base my schedule around some simple heuristics: three hours a day on deep work for research, and a list of small things to schedule each day into the time that remains.

I would never get away with this approach during the height of the school year, but for a lazy week in July, it worked perfectly.

The bigger message here, however, is that I always decide in advance what I am going to do with my week. These decisions look different at different times of year, but what matters is that when it comes to my schedule, I’m in charge.

August 4, 2014

Stop Looking for the “Right” Career and Start Looking for a Job

A Reality Check from Mike Rowe

Mike Rowe and I agree that “follow your passion,” as a piece of advice, tends to make people more unhappy about their working life.

A reader named Steve recently pointed me toward a hilarious and yet profoundly relevant example of Rowe articulating this position.

Allow me to set the scene…

Rowe receives a piece of fan mail that opens as follows: “I’ve spent this last year trying to figure out the right career for myself and I still can’t figure out what to do.”

Rowe then responds. In his response, he explains, without apology, exactly why this complaint is dumb.

I won’t spoil the whole thing (you can read the original letter and Rowe’s full reply here), but I do want to point your attention to my favorite paragraph:

Stop looking for the “right” career, and start looking for a job. Any job. Forget about what you like. Focus on what’s available. Get yourself hired. Show up early. Stay late. Volunteer for the scut work. Become indispensable. You can always quit later, and be no worse off than you are today. But don’t waste another year looking for a career that doesn’t exist. And most of all, stop worrying about your happiness. Happiness does not come from a job. It comes from knowing what you truly value, and behaving in a way that’s consistent with those beliefs.

In my opinion, you could substitute the above suggestions for just about any commencement address that was given this past spring, and the students would have ended up much better prepared for the real world.

Well said, Mike.

July 31, 2014

Do Goals Prevent Success?

An Effectual Understanding of Impact

I’ve long been interested in the idea of the impact instinct: the ability for a trained professional to continuously generate big wins at a rate much higher than his or her equally well-trained peers (see here and here and here).

What explains this impact instinct?

A reader named Jason recently pointed me toward some interesting research relevant to this question. The topic is effectuation, a theory of entrepreneurial success devised by Saras Sarasvathy (see above), a professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business.

The origin of effectuation is a study Sarasvathy conducted in 1997. She traveled the country to interview 30 different entrepreneurs who founded successful companies (their company valuations were all measured in hundreds of millions of dollars). Instead of simply asking them their approach to business, she had each solve a 17-page problem set containing 10 decision problems relevant to introducing a new product. She asked that they talk out loud about their thinking, and then later scrutinized the transcripts of these sessions. The patterns she identified became effectuation theory.

In a nutshell, this theory notes that we’re used to thinking about problems (especially in the business world) using causal rationality. We identify a goal and then attempt to identify the optimal path to accomplishing this goal given our current resources. This process is top-down with the final goal occupying the apex position.

The entrepreneurs Sarasvathy interviewed did not rely on causal thinking. They instead relied on an alternative she called effectuative thinking.

Effectuative thinking, unlike causal thinking, is bottom-up. It doesn’t start with a final goal in mind. Instead, as Sarasvathy explains, “it begins with a given set of means and allows goals to emerge contingently over time.”

Sarasvathy identifies four main principles to approaching your work in this manner:

Start with what you already know how to do well.

Filter your efforts to avoid big downsides not to select for big upsides.

Work with other people who bring new abilities to the table.

Take advantage of the unexpected .

If you approach a new business using these guidelines, you might not know in advance your main product or even your market, but according to this theory you’re optimizing your chances of nonetheless ending up successful.

Here’s Sarasvathy describing effectuation in action:

“Plans are made and unmade and revised and recast through action and interaction with others on a daily basis…Through their actions, the effectual entrepreneurs’ set of means and consequently the set of possible effects change and get reconfigured. Eventually, certain of the emerging effects coalesce into clearly achievable and desirable goals — landmarks that point to a discernible path beginning to emerge in the wilderness.”

An analogy that helps me understand these issues is that the marketplace can be described as an unpredictable and complex landscape with only a small number of peaks representing massive potential.

Causal thinking has you try to draw a map to a peak in advance. Given the complexity of the landscape, this is likely to fail. Your best bet is that your map, by pure luck, happens to lead you straight to a high peak.

Effectual thinking, by contrast, has you hone your navigation skills. It teaches you how to systematically search the landscape around you, bringing along guides that know the area, and keeping you attention tuned to the tell-tale signs of elevation gain.

There are, of course, other business trends that echo similar ideas (think: lean methodology). But what’s nice about effectuation is that its principles are presented in a general way that seem applicable beyond the world of business start-ups.

The reader who brought this work to my attention, for example, is involved in a study to see if effectuation explains star academics (the original question that piqued my interest about such issues).

One could imagine the same theory being just as applicable to explaining consistent success in other fields, such as book writing or even personal productivity.

At the very least, Sarasvathy’s scientific results underscore what I’ve long argued: the process of becoming a stand out in almost any field is way more nuanced and complicated than most suspect.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers