Cal Newport's Blog, page 51

March 30, 2014

Deep Habits: Using Milestones to Get Unstuck

In Search of Productive Simplicity

Last week, I described a kink in my project productivity systems. I was oscillating, somewhat haphazardly, between two different strategies, tracking hours (e.g., when the work is open-ended), and pursuing milestones (when the work is known and I need to hustle).

This felt too complicated, so I asked for your thoughts and you responded with over thirty suggestions.

A lot of your advice seemed to fall into the category of “different work requires different tools, switch as needed.”

This is probably good counsel.

But it still nagged at my preference for simplicity in such matters (which, as a theoretical computer scientist, I of course measure in terms of Kolmogorov complexity).

Then I got an e-mail from an academic in a field that also requires proof-style work (e.g., problems for which the process to completion is unknown in advance). He explained how he approaches projects:

Milestones for me. In [my field] I hit roadblocks and dead ends which force me to start over or take off in a different direction.

After asking him some clarifying questions, I filled in the details. When working on a complex problem, he would set a key milestone and attack it. If he failed to reach the milestone, he would then ask “why?”, and react accordingly:

If his answer is “I didn’t spend much time on it,” then he knows the next step is to put aside more time in the near future to work deeply.

If his answer is, instead, “I did spend enough time on it, but I didn’t get anywhere,” then he’s forced to either: (a) identify a brand new approach and tackle the same milestone again with this new approach; or (b) move on to an unrelated milestone.

To summarize, this approach focuses on milestones of the form “accomplish X by Y” (not hour tracking), but when a milestone is missed, it generates an immediate postmortem to figure out what comes next.

Once I understood these details, the full simplicity and power of this approach resonated with me. This academic was reacting to an important truth that I was overlooking: the difficulty of hard-to-predict processes — like solving proofs — is not just making sure you put in the time, but also making sure you don’t waste time stuck in a cul-de-sac (to borrow a Seth Godin term).

Stated more concretely: it’s likely way more productive to spend five hours each on three different approaches to a problem then to spend fifteen hours stuck on one approach.

This milestone-centric strategy is inspired by this reality. There are two reasons why it appeals to me:

First, I love the simplicity of using a single tool to unify how I approach the various important projects in my life.

Second, it resonates with my experience: if I fail to prove something with a given approach after, say, 5 – 6 hours, I’m likely never going to succeed with this approach. I either need to try something new, read something new, talk to someone, or move on to a new problem, keeping this one in the back of my mind in case I later come across a relevant new tool (a common trick of Richard Feynman).

I need to try this approach more extensively before declaring it successful. And it likely does not apply to many fields outside my own. But I thought it might be interesting to offer some insight into the meta-thinking that supports a lot of what I do.

More importantly, it’s a good excuse to bring up Kolmogorov.

March 23, 2014

Deep Habits: Should You Track Hours or Milestones?

Meaningful Metrics

Some of you have been requesting to hear more about my own struggles to live deeply in a distracted world. In this spirit, I want discuss strategies for completing important but non-urgent projects. In my experience, there are two useful things to track with respect to this type of work:

Specific milestones: for example, the number of book chapters completed or mathematical results proved.

Hours spent working deeply toward milestones: for example, you can keep a tally of the hours spent writing or working without distraction on an important proof.

In my own work life, I find myself oscillating between these two types of metrics somewhat erratically, and I’m not sure why.

A Hybrid Approach

Part of my confusion is that both approaches have pros and cons.

The advantage of tracking milestones, for example, is that the urge to achieve a clear outcome can inspire you to hustle; i.e., drop everything for a couple days and just hammer on the project until it gets where you need it to be. Sometimes my projects fall into a state of stasis where hustle of this type is needed to get unstuck.

The advantage of tracking hours, on the other hand, is that many of the important but non-urgent projects I pursue cannot be forced. I can commit, for example, to finishing a proof in a week, but this doesn’t mean I will succeed. Some proofs never come together; some take months (or years); others fall quickly. It’s hard to predict. Tracking hours in this context ensures, at the very least, that these projects are getting a good share of my time, even if I can’t predict what will finish and when.

When it comes to productivity, I’m a big believer in simplicity. My oscillation between the different styles of methods described above strikes me as non-simple.

At the current moment, for example, I’m tracking deep hours on my key research projects (see the image above), but I also have a milestone plan for this work that seems to be almost completely useless. I think I maintain the latter because of an ill-defined sense that I need to add more hustle into the mix here.

When it comes to writing, I’m currently working on a big project (more on this later). I tried, but then quickly abandoned, an hour tracking approach to this work. Right now I’m having much more success hustling to hit carefully chosen milestones; probably because this work is more predictable.

I’m left, in other words, with a relatively confused jumble of approaches to keeping myself on track with big projects. I’m happy with the rate at which I’m producing, but I can’t help but wonder if: (1) I could be producing even more with my (well-defined and contained) working hours; or (2) if the scheduling and tracking of this production could be greatly simplified, and, in turn, simplify my life.

This is something I’m thinking a lot about recently. I’d be interested to know if you are too, and if so, what you’ve discovered works (or does not).

March 17, 2014

Would You Buy a Yard Tool if You Had No Idea What to Use it For? So Why Would You Sign Up For Snapchat?

The Amazing Roto-Mill

I’ve been toying with a (potentially) interesting thought experiment recently. Imagine you walk into a hardware store and a helpful clerk comes up to you holding a weird looking tool.

“Here’s our latest and greatest lawn care tool,” he explains. “It’s called a roto-mill. It has a reinforced auger head that spins at 1600 RPM.”

“Why do I need a roto-mill?”, you ask.

“I don’t know,” he replies. “I want you to buy it, take it home, dedicate a few hours every weekend to trying it out in your yard, seeing if you can find a use for it. Who knows, you might even find it fun.”

“But I have other things to do on the weekends,” you protest, “things I know are useful and things I know are fun.”

“If you don’t dedicate your time and attention to working with this roto-mill,” the clerk warns, “you might miss out on some benefit that we’re not thinking of now. I don’t see how you could afford such a risk in today’s age of modern yard tools.”

A (Contrived) Analogy

This dialogue, of course, is contrived, but you’d likely agree that if you were that customer, you’d walk out of the store, perhaps worried that the clerk was mentally disturbed.

What intrigues me, however, is that this is essentially the same conversation many have with high tech companies when they release their latest, greatest social media tools. If we replace the word “roto-mill” with “snapchat,” for example, the above suddenly seems more familiar and somehow less absurd.

But why?

I’m the first to admit that this thought experiment is not perfect: there’s money involved in buying a yard tool, but not so directly involved in trying an online tool; entertainment is perhaps not being valued fairly; etc.

But still, an interesting Monday afternoon thought…

(Image by Lance Fisher)

March 2, 2014

The Student Passion Problem

The Double Degree

A reader recently pointed me to the following question, posted on Stack Exchange:

I am studying a combined bachelor of engineering (electrical) and bachelor of mathematics; I just started this year and will graduate in 2018. The reason why I am doing double degrees and not a single degree is because I love both electrical engineering and mathematics and I could not ignore any of them. So with this in mind, I am thinking of doing two PHDs when I graduate (one in electrical engineering and one in mathematics). Is this a good path or I should concentrate on only one of them?

The responses in the comment thread for this question are fantastic, but in this post I want to add an additional thought to the conversation.

The Student Passion Problem

Over the past few years, I’ve been writing a lot about the negative impact of the passion mindset on recent graduates. The above question reminded me that it is easy to forget this mindset’s negative impact on those who are younger, especially students.

(Indeed, I was first introduced to the problems surrounding passion when advising undergraduates struggling with their choice of major.)

The above student is a perfect example. He feels compelled to maintain a double major (and perhaps even an absurd double PhD) in two hard fields, which, as I’ve argued here and here and here, is a recipe for unnecessary stress and burnout.

Why does he feel compelled to make this sacrifice? He “loves” both fields.

From an objective perspective, what does it mean for a second semester freshman to “love” electrical engineer or mathematics? At best, it means he enjoyed a handful of courses on the topic and/or thinks it sounds interesting.

To feel real passion for an academic subject, by contrast, requires years of honing your craft. Until then, you’re pursuing an idealized simulacrum.

The obvious advice to this student, then, is to choose one of these topics that interest him and then invest the time necessary to learn the craft and develop a true connection to the material. In fact, as long time Study Hacks readers know, this strategy of doing a small number of things really well is my number one piece of advice for college students looking to enjoy life and have interesting options after graduation.

But the passion mindset that dominates our culture corrupts this thought process. Because we’re taught at an early age that we have preexisting inclinations that matter above all else, it’s easy to mistake any idle interest or yearning as an obligatory pursuit — regardless of the consequences.

In other words, when talking to students about passion, it might be better to present college as a place to learn to develop passions, not follow ones that you’ve convinced yourself somehow already exist.

(Photo by JSmith Photo)

####

Student overload is on my mind as I’m heading up to Middlebury on the 10th to give my talk on escaping the cult of overwork. If you’re in the area, I encourage you to attend.

February 26, 2014

A Useful Reminder: Louis C.K. Was Bad Before He Was Good

The Evolution of Louis C.K.

I sometimes listen to a stand-up comedy channel on Pandora. Driving home the other day, it served up an old clip of Louis C.K.

Here’s what surprised me: he wasn’t that good.

His material wasn’t original (one of his gags was about wearing adult diapers) and his pacing was rat-a-tat-tat night club style.

Louis C.K. today, of course, is an exceptional comedian — arguably the best stand-up in the business at the moment.

I bring this up, because American culture (similar to ancient Greek culture) likes to attribute significant accomplishment to outside sources. Whereas the Greeks attributed moments of great heroism or creativity to the presence of the relevant God, Americans love stories of prodigies imbued at birth with stunning talent, or people driven with clarity to their destiny by an unmistakable passion.*

These stories are compelling, but I’m more drawn to narratives like Louis C.K. — narratives of people who polish their craft deliberately, night after night in crappy clubs and hothouse writer rooms (C.K. honed his asburdism writing for Conan O’Brien), then, one day, look up and are surprised to realize that they’ve become a star.

#####

* Please don’t, at this point, tell me that Louis C.K. persisted only because he had a clear passion for comedy. This necessity-of-pre-existing-passion fairy tale is common but I think just as absurd as depending on a Greek God to guide you. Work and life is complicated. Comedians like C.K. suffer from extensive insecurity and doubt. They don’t wait to feel like they are doing the right thing, they work hard to make it the right thing.

February 23, 2014

Should Gatekeepers be Bypassed or Embraced?

The Gatekeeper Complex

I recently stumbled across an interesting podcast about fiction self-publishing, titled, appropriately enough, the Self-Publishing Podcast. The show is hosted by three fiction writers who are experimenting with a new model for genre fiction production, based on book series fueled by funnels (think: first volume free).

Something that caught my attention about this show is the tagline read by the host at the beginning of every episode:

The podcast that’s all about getting your words out into the world without contending with agents, publishers, or the other gatekeepers in traditional publishing.

I’m highlighting this statement because I think it captures a sentiment common in the DIY/Lifehacker world: gatekeepers (book editors, admissions officers, venture capitalists, prestigious academic journals, etc.) are obstructing your quest to do interesting and valuable things.

I understand this sentiment: this is a heady time when lots of innovation is happening in lots of fields.

But…

In my career to date in both academia and publishing, I’ve found that traditional gatekeepers play a crucial — and hard to replicate — role that anyone interested in creative work should not be quick to ignore.

Gatekeepers, it turns out, are really good at two things: (1) assessing value in their field; and (2) providing ruthlessly honest feedback on this value (usually in terms of a swift rejection if something falls short).

Students of deliberate practice should immediately recognize the congruence between this function and that of a good coach. I’m arguing, in other words, that gatekeepers can be used to help push your creative skills to new levels.

To provide some personal examples…

To prepare to sell my first book, I pitched advice articles to college-focused magazines. The gatekeepers at these magazines aren’t going to send you a check unless you have something interesting to say and you say it well. This helped push my advice-writing ability past the threshold needed to sign a book deal with a major publisher.

In my academic work, when I have a new approach or idea I think is important, I start by trying to publish papers in prestigious venues. If it cannot pass rigorous peer reviews, I figure, an idea is not ready to become a major focus of my research (and grant-writing) attention.

Returning to the Self-Publishing Podcast, the hosts of this show are accomplished professional writers who have honed their craft. It makes sense for them to explore alternative fiction publishing models.

(I should emphasize that traditional non-fiction publishing has served me exceptionally well, but from what I understand, fiction publishing is a completely different beast; one in which the self-publishing conversation is more relevant.)

But when I think about the novices listening to this podcast, I can’t help but wonder if they would be even better served if they were told to first strive to do what it takes to sign a book deal with a major publisher, and only then, after honing their skill to a point of unambiguous value, step back and ask, now what do I want to do with this asset?

February 14, 2014

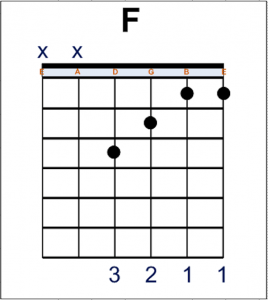

Where’s Your F Chord? What Guitar Teaches Us About the Quest for Mastery

The Deliberate Strummer

The Deliberate Strummer

The first step in learning guitar is mastering the major chords. As any new player will tell you, it’s not difficult to learn where your fingers are supposed to go for each chord, the real challenge is training your finger muscles to actually hit the desired positions cleanly.

Of all the major chords, this challenge is most pronounced for the F (pictured above), which not only keeps your fingers devilishly close together on the fretboard, but also requires you to contort your index finger to somehow flatten two strings at once.

There’s no shortcut to learning how to play an F: you have to force your hand into the cramped position, again and again, picking up the speed as soon as you become too comfortable.

Each of these attempts (literally) strains you. This is not Guitar Hero: it’s uncomfortable and not at all fun.

But if you stick with it, your muscle memory improves, and you get faster and cleaner. Then, one day, you’re able to play House of the Rising Sun.

I’m bringing this up because learning to play the F chord provides a perfect case study of deliberate practice. It’s a clear goal that requires you to stretch your current ability and provides immediate and clear feedback on your progress. It’s also a goal that provides tangible rewards if achieved.

Accordingly, it provides a nice analogy when assessing your own work habits. When surveying how you spend your time, it helps, in other words, to ask “where’s my F chord?”

To ask this question is to ask where in your schedule is the time dedicated to straining yourself (uncomfortably) to master something that you can’t do now but would be valuable if you could.

This type of deliberate effort is a pain. It’s why most people give up learning to play the guitar (and why my skill level plateaued pretty quickly when I was younger*).

It’s also why so many knowledge workers end up glorified e-mail sorters, nervous at every round of layoffs.

But here’s the thing (if you’ll excuse the abuse of this analogy): if you’re not willing to strain your fingers, you’ll never end up the professional equivalent of the cool guy, surrounded by girls, strumming soulfully to House of the Rising Sun.

###

* See Part 2 of SO GOOD for more on my guitar playing career and its relevance to understanding deliberate practice.

February 2, 2014

The Empty Sky Paradox: Why Are Stars (in Your Professional Field) So Rare?

The Empty Sky Paradox

In many fields, people are eager to produce top results. A non-trivial fraction of the Internet is dedicated to tips and hacks for accomplishing this exact goal.

So why are so few people stars?

This past week provided me a good opportunity to reflect on this question. I attended a Dagstuhl seminar on wireless algorithms, which means I spent a week in a castle (pictured above), tucked away in rural west Germany, working with top minds in my particular niche of theoretical computer science.

Here’s what I noticed:

In theory, the people who tend to consistently produce important work seem to be those who consistently take the time to decode the latest, greatest results in their subject area.*

Only when you’re at the cutting edge are you well-positioned to spot and conquer the most promising adjacent intellectual territory (for more detail on this idea, see Part 3 of SO GOOD).

This sounds like simple advice — stay up to date on the latest work! — but most practicing researchers probably don’t follow it. Why? Because this turns out to be incredibly hard work.

(These results are tricky, and presented in short conference papers where key mathematical steps are elided, requiring days [and sometimes much more] to decode.)

This brings me back to the general question of why most fields have so few stars. The answer, I conjecture, is that most fields are similar to theoretical computer science in that the path to becoming a standout includes a prohibitively difficult step. It’s this step that limits stars, as most people simply lack the comfort with discomfort required to tackle really hard things.

At some point, in other words, there’s no way getting around the necessity to clear your calendar, shut down your phone, and spend several hard days trying to make sense of the damn proof.

(Photo by Nic McPhee)

###

* This is a skill that I’ve been systematically developing for the last three to five years. I’m better than I was, but not yet as good as I want to be. I can attest from personal experience that these proof decoding efforts: (a) are extremely difficult — deep work purified to its most stringent form; (b) are crucial for producing useful results; and (c) get easier (though, quite slowly) with practice.

January 17, 2014

Forget Ideas. Focus on Execution.

Beyond the Impact Instinct

Study Hacks readers know that I’m fascinated by Erez Lieberman Aiden: an absurdly accomplished young professor who racked up three covers in Science and Nature by the age of 33.

In an earlier post on Aiden, I hypothesized his “secret” was a well-develop impact instinct that allows him to hone in on attention-catching problems.

After reading a recent Chronicle of Higher Education profile of Aiden (in which I’m quoted), however, I’m beginning to suspect I was wrong…

My suspicion began with the following quote about Aiden, provided in the Chronicle profile by one his colleagues:

[1] He can really recognize a good problem, [2] quickly learn what kinds of methods are out there that might be useful in solving it, [3] somehow combine those into a new concept, and [4] identify experts in those fields to work with.

This quote lists four traits (the numbering is mine). The first is about coming up with a good idea, but two through four all deal with the “nitty-gritty” details of transforming a vague notion into concrete and impressive results.

Later in this profile, these traits are elaborated when we learn about the multiple obstacles Aiden and his collaborators faced in building the Google n-gram viewer (which became the source of much of his recent attention):

The meta-data was messy: so they developed a new algorithm to clean it up.

Google got cold feet about letting Aiden have access to their data: so Aiden convinced Steven Pinker to join the project to help them bypass red tape.

And so on.

This article, in other words, helps crystallize a reality that I have increasingly recognized in my own career: coming up with good ideas is easy; executing them at an elite level is staggeringly difficult.

###

My friend Josh Millburn, of The Minimalists fame, just published a memoir about his transition to simplicity: Everything that Remains. I found it compelling — a more literary look at a world often confined to the how-to genre. If you’re interested minimalism, check it out.

(Photo of Erez at TED Boston by Ritterman)

January 12, 2014

New Year’s Advice from Epictetus: Don’t Get Started

The New Year, of course, is celebrated as a time to commit to bold new ideas. American culture emphasizes this period because we valorize action.

(If you doubt this attitude, watch an episode of ABC’s Shark Tank, a show in which a cattle call of budding entrepreneurs are invariably praised for their courage, even though most put their family into massive debt to produce an ill-fated injection molded trinket.)

I find it useful during this giddy season to remember that an emphasis on getting started, though currently popular, is not timeless.

Case in point, my friend Dale Davidson recently sent me a smart quote on this subject from the first century stoic philosopher, Epictetus:

In every affair consider what precedes and follows, and then undertake it. Otherwise you will begin with spirit; but not having thought of the consequences, when some of them appear you will shamefully desist.

Epictetus doesn’t reject action. But he believes commitment to a pursuit must be preceded by the careful study of what is actually required for success.

He uses the Olympic games as an example. He notes that participating in the event seems glamorous on the surface, but a closer examination of what this requires reveals that you must:

…conform to rules, submit to a diet, refrain from dainties; exercise your body, whether you choose it or not, at a stated hour, in heat and cold; you must drink no cold water, nor sometimes even wine.

For most budding ancient athletes, Epictetus implies, this reality would likely dim the glamor of pursuing the Olympics. But not for everyone. As he then concludes:

When you have evaluated all this, if your inclination still holds, then go to war [emphasis mine].

I like this decision-making framework.

When considering a major endeavor, Epictetus teaches, first master its reality. This requires that you put aside your vision of how a pursuit should unfold, and embrace the reality of what’s actually required to succeed (a surprisingly difficult, and often sobering endeavor).

Most ideas subject to such scrutiny will end up discarded.

To Epictetus, that’s fine.

What matters is that when you come across that rare pursuit for which your inclination still holds — even after a thorough examination — you “go to war.”

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers