Cal Newport's Blog, page 50

July 22, 2014

Don’t Pursue Promotions: Contrarian Career Advice from Ancient Sources of Wisdom

An Innovative New Voice in the Advice World

For the past six months, my friend Dale Davidson has been executing an epic project.

Eager to optimize his life, and frustrated with much of the advice he encountered online and in contemporary books and magazines, Dale decided to go back to basics and start drawing lessons from humankind’s most ancient and enduring philosophies and religions.

To do so, he focuses on one ancient philosophy or religion per month. During this month he chooses a core ritual to practice. He then extracts wisdom relevant to his modern life from these ancient prescriptions.

The logic driving his project is simple. These systems have undergone centuries — and in many cases, millennia — of brutal cultural evolution. The ideas that survived this competition must have done so for a good reason: they work.

Why start from scratch in finding answers to life’s challenges, big and small, when you can reference the solutions human civilization has already painstakingly developed and tested?

I’ve been fascinated by Dale’s progress with this project, which he details on his Ancient Wisdom Project blog. I think more people should know about what he’s up to, so I asked him to write a guest post for me.

Below is the (epic) result. In the guest post that follows, Dale briefly summarizes the structure of his project, then identifies five contrarian tips he’s learned so far. To keep the article relevant to our recent discussions, I asked Dale to focus on tips relevant to career issues.

Some of the ideas below you may agree with and some you may not. But they should all get you thinking more deeply about how you approach success and happiness in your career…

Take it away Dale…

[Note: From this point on the text is written by Dale. -- Cal]

Returning to Ancient Wisdom

During college, all I wanted to do was become a Navy SEAL. I won an NROTC scholarship, got accepted into training, and was ready to start my career as an operator.

Unfortunately, once I got to training, I realized I didn’t want to become a SEAL, and I quit.

Not knowing what to do with my life, I looked to bloggers for help. I discovered Tim Ferriss, and decided that what I needed to do was build a passive-income web business and travel the world.

So I did. I started a (unsuccessful) web business, took off to Egypt to teach and travel, and tried to create the life I thought would make me happy.

The thing is, I wasn’t happy. None of the standard blogger advice worked for me. I felt like I would never have a meaningful career or professional life, that there was something fundamentally wrong with me.

So a few months ago, I changed strategies. I started to look outside the blogosphere for help. I began studying and practicing ancient religion and philosophy to figure out how to live a meaningful life. Over time, I added some structure to this project and began to blog about it: calling the whole endeavor the Ancient Wisdom Project.

Ultimately, I settled on the following rules to structure my efforts:

Every month I identify one positive trait or quality I’d like to cultivate in myself (tranquility, compassion, etc.).

I then choose an ancient religion or philosophy that I believe will help me develop that particular trait. These philosophies or religions must be sufficiently ancient (at least 500 years or so) and must still exist in some form today.

After I match the religion with the trait, I select one practice from the religion to adopt for a 30-day period that I feel will be particularly useful. Ideally it’s a practice that I can perform on a near daily basis.

Then I do the practice for a one-month period and study the ancient philosophy or religion in order to maximize the effectiveness of the practice.

Finally, I write about the experience on my website.

For example, the first trait I wanted to cultivate was tranquility. After a bit of research, I decided that Stoicism would be perfect for helping me develop this trait.

I then decided to adopt one physical practice and one mental practice.

For the physical practice, I decided to take daily ice baths, (to expose myself to physical hardship), and for the mental practice, I chose negative visualization, the act of imagining all the ways your life could be worse.

Dale attempting to look upbeat in a Stoic ice bath.

Over that 30-day period of ice baths and negative visualization, I learned the importance of managing my perceptions of external events and observed noticeable improvement in my daily anxiety level.

Over the past few months, I’ve explored many sources of ancient wisdom (e.g., in addition to Stocism, Catholicism, Judaism, and Islam). In this blog post, I want to identify several unexpected pieces of advice from these experience. I will focus, in particular, on advice relevant to your career.

These ideas are not what lifestyle designers will tell you to do, and they aren’t always as easy to follow as what you might find in the standard Business Insider click-bait story.

But they’re based on insights that formed over thousands of years of cultural evolution, and therefore represent some of humankind’s best thinking on these issues.

I hope you find this advice as useful as I have…

Contrarian Career Advice from Ancient Sources

Tip #1: Don’t pursue promotions

Promotions are wonderful tool for companies to motivate its employees. They’ll say that if you work hard, you can get a raise and a fancy new title.

For many employees, this is a worthwhile pursuit. There is nothing like external validation and more money to make you feel good about yourself.

But there are two problems with approaching your career this way:

First, promotions are not within your control.

There are a few reasons for this. There are a limited number of positions and titles in any given company. You are restricted by the inherent supply of positions that are available to you.

In addition, someone else will ultimately decide whether you receive a promotion. It might be your boss, it might be a committee, but it’s not you. You can’t waive a magic wand and give yourself a promotion.

Stoicism, an ancient Greek philosophy, teaches that you should only desire things within your control. Otherwise, you are doomed to be unhappy.

And what is within your control? Here’s what Epictetus, a slave turned Stoic sage has to say [Note: All cited passages in this section are from Epictetus]:

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.

Promotions don’t fall into the list of things you can control, therefore, you shouldn’t desire promotions. If you receive one, you’ll soon get used to the new title and larger salary and begin desiring the next promotion. If you are passed over for one, you will be unhappy.

The second major reason you shouldn’t seek promotions is that it is likely you will have to compromise something you value in order to attain one.

Are you a creative type in a conservative company? Well, it’s unlikely that you’ll get a promotion without hiding your creativity to some extent.

Do you like to work on your own but your company emphasizes teamwork? If you stop showing up to meeting, people will question your dedication to the mission.

The pursuit of a promotion will come at a price, and it will sometimes be a price you shouldn’t pay.

Is anyone preferred before you at an entertainment, or in a compliment, or in being admitted to a consultation? If these things are good, you ought to be glad that he has gotten them; and if they are evil, don’t be grieved that you have not gotten them. And remember that you cannot, without using the same means [which others do] to acquire things not in our own control, expect to be thought worthy of an equal share of them. For how can he who does not frequent the door of any [great] man, does not attend him, does not praise him, have an equal share with him who does? You are unjust, then, and insatiable, if you are unwilling to pay the price for which these things are sold, and would have them for nothing.

Cal says that you should become so good they can’t ignore you. I agree that you should become “so good,” as that is in your sphere of control, but I say you should be indifferent to whether or not others ignore you. The Stoics would say instead:

“Become so good and stop worrying if others ignore you.”

If you happen to win praise and recognition for your good work, great! Just don’t let it get to your head. If you do good work and no one cares, be indifferent.

But, for your part, don’t wish to be a general, or a senator, or a consul, but to be free; and the only way to this is a contempt of things not in our own control.

Tip #2: Cultivate humility

If you’ve ever taken part in a workplace gripe session with your friends, you know that the conversation usually includes complaints about “idiot coworkers” or “clueless management.”

The universality of these comments would make you believe that all employees and bosses everywhere are clueless or evil idiots whose only purpose is to make your work life miserable.

We know this to be false, so what explains this phenomenon?

When you say your co-worker or boss is an idiot, the hidden assumption is that you are better than them as human beings. You are not conducting a dispassionate analysis of their behavior and coolly explaining how they can do things better, you’re just being arrogant.

This arrogance is making you miserable.

The word Islam, means “submission [to God’s will].” Implied in this definition is that you are not the center of the universe, that you shouldn’t follow your own desires, you should follow God’s desires.

Dale learning Islamic prayer techniques.

Focusing less on yourself is a key component to humility. Islam reinforces humility by requiring Muslims to pray five times a day (the practice of Salat), which includes a physical act of prostration.

Islam didn’t just teach people to practice humility towards God; they also taught that it was important to be humble in the way you relate to others.

Rumi, a famous Sufi poet, once said, “The fault is in the one who blames. Spirit sees nothing to criticize.”

Criticism of your co-workers is not really about them, it’s about you and your own issues.

In my own experience, I found that by practicing humility, I became happier at work, or at least, less frustrated. If a co-worker did something I thought was dumb, I would ask myself “Am I capable of making similarly stupid mistakes? [Yes I am]” When I thought senior management was making a stupid strategic decision, I asked myself, “Do I know how to run a company better than they do? [No I don’t]”

Cultivating a humble attitude towards others at your work will yield better emotional and psychological results than venting at happy hour with your friends.

Tip #3: Ditch work-life balance in favor of sacred rest

Work-life balance is a hot topic at the moment. We live in an age of distraction and fluid boundaries between work and the rest of our life. We answer work e-mails at home, personal e-mails at work. “Leisure” doesn’t even seem that relaxing. I’m guilty of binging on Netflix for hours and hours on the weekend. When I’m done, I feel sluggish and unhappy. I’m not working, but I’m not quite resting either.

Modern advice that advocates work-life balance doesn’t go far enough. Even the term “work-life balance” doesn’t convey the importance of what we need to truly flourish as human beings.

What we need is something like Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest.

Shabbat begins on Friday night and ends on Saturday night. If strictly observed, you are not allowed to cook, write, or really do anything that would be considered work. You are also prohibited from using electronic devices, as that would be considered “igniting a fire,” (due to electrical sparks in the circuitry of the device).

Does this seem outdated? Overly strict?

I don’t think so. To truly rest, you need to commit yourself to activities that are meaningful and rejuvenating, and ruthlessly cut out those that aren’t.

When you can’t use your iPhone, buy anything, or even drive, you will naturally do activities that are inherently meaningful. You will spend time with your family, go out for long walks, have fun conversations over long meals (with food you prepared before Shabbat), etc.

It reminds you that you have a life outside of work, that humans aren’t “beasts of burden,” that our purpose here on Earth goes beyond your career or job.

Consider these words from Abraham Joshua Heschel, a famous Jewish theologian,

“The Sabbath is a day for the sake of life. Man is not a beast of burden, and the Sabbath is not for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of his work. ‘Last in creation, first in intention,’ the Sabbath is ‘the end of the creation of heaven and earth.’

The Sabbath is not for the sake of the weekdays; the weekdays are for the sake of the Sabbath. It is not an interlude but the climax of living.”

Instead of complaining that your work is taking over your life, make some portion outside of your life sacred, so you can truly feel rejuvenated.

Cal says that to achieve a remarkable career, we need to learn the art of deep focus at work.

Judaism would say to achieve a remarkable life, we need to learn the art of deep focus at rest as well.

Tip #4: Pay close attention to your feelings

I’ve been a slave to my emotions about my work. During particularly boring work assignments, I’ve fantasized about quitting my job to start a passive income business and traveling the world. In moments of anger, I’ve wanted to yell at my boss, make a dramatic speech to my co-workers, and storm out of the office.

I found that most lifestyle design bloggers play upon these (normal) feelings and use it to promote bad advice that will lead you to make bad decisions. If your job is boring, they will tell you to quit for an exciting life as an entrepreneur. They will tell you to find your passion or travel the world regardless of what your individual circumstances are.

Your feelings are important, but you need to learn how to correctly assess your feelings in order to make good decisions.

For this, you should follow the Jesuit (a Catholic order) process called the “Discernment of Spirits.”

Father Kevin O’Brien, a Jesuit priest, writes:

In discernment of spirits, we notice the interior movements of our hearts, which include our thoughts, feelings, desires, attractions, and resistances. We determine where they are coming from and where they are leading us; and then we propose to act in a way that leads to greater faith, hope, and love.

We pay attention to feelings of consolation, “…an experience of being so on fire with God’s love that we feel impelled to praise, love, and serve God and help others as best as we can,” and desolation, “an experience of the soul in heavy darkness or turmoil.”

There are a number of rules to follow when practicing discernment that are unexpectedly sophisticated for a practice that is 500 years old.

For example, take the Third Rule:

“With cause, as well the good Angel as the bad can console the soul, for contrary ends: the good Angel for the profit of the soul, that it may grow and rise from good to better, and the evil Angel, for the contrary, and later on to draw it to his damnable intention and wickedness.”

What this says is that just because something your doing feels bad or painful, it doesn’t mean the activity itself is bad.

Say you’re on a particularly stressful project at work. You feel exhausted and frustrated, and you think you should quit your job.

A lifestyle design blogger would say, “of course you should quit! A job you love would never feel stressful or difficult.”

A Jesuit, on the other hand, would ask you if maybe these feelings are temporary, and that if the project is a good one, maybe it’s worth completing. It asks you to consider that maybe the “bad angel” is trying to trick you into abandoning a worthwhile effort.

You may protest that you don’t believe in angels or God or spirits, but that’s not the point. The point is that the Jesuits had an advanced process for paying attention to your feelings that will help you make good decisions and avoid bad ones. The process is careful, methodical, and more importantly, tested over centuries of human experience.

I’ve used discernment when assessing whether or not I should stay at my job. My job generally leaves me with feelings of desolation. It may seem obvious that I need to quit, right?

Wrong. Using discernment, I discovered what I needed was to do something meaningful and that it didn’t have to come from my job.

So what did I do? I started volunteering at a homeless-services organization. I spend a few hours every month serving meals to the homeless. This has provided an immense boost to my happiness.

Do I still have negative feelings about my job? Of course, but I found a way to make it tolerable, which gives me time to assess what I really want to do for my career.

If a 500-year old Jesuit practice can help me, an agnostic, it can certainly help you too.

Conclusion: The ancients were wise; you should listen to them

None of this advice is as easy or as sexy as the standard, “quit your job, follow your passion” advice that Cal has quite smartly pointed out is nonsense.

It’s not that lifestyle design bloggers are purposely trying to lead you astray; I believe they are really trying to help people have meaningful lives and careers.

However, their greatest weakness is that their advice is not time-tested. Careers are fairly new inventions, and we’re all trying to figure out how they fit with our lives, so the fact that there is lots of bad advice out there is not surprising.

The ancients did not attempt to provide career advice per se (though some did), but they did teach people how to live good and meaningful lives in a world that is often cruel and indifferent to our desires. This same advice which has helped billions of people over thousands of years is still relevant to our modern lives and, can help us navigate even modern artifacts, like our careers.

To live a good and meaningful life, you’re better off following the example of philosophers like Epictetus, Catholic heroes like Saint Ignatius, or Islamic prophets like Mohammed than you are of following advice from the latest lifestyle design blogger.

But what do I know? I’m just a 26-year old blogger.

July 4, 2014

How to Read Proofs Faster: A Summary of Useful Advice

The Wisdom of (Math Nerd) Crowds

A couple weeks ago, I complained that my academic paper reading speed was slower than I would like given its importance to my productivity. I asked for your advice and you responded with over 60 comments and numerous private e-mails.

My goal in this post is to synthesize the best ideas from this feedback, as well as the results of my own self-reflection, into a clear answer. In particular, I’ve identified three big ideas relevant to trying to read technical papers — and in particular those containing mathematical proofs — as efficiently as possible.

Idea #1: There are no magic bullets…

This conversation helped cement an idea that I’ve long suspected to be true (but sometimes resist):

To develop a detailed understanding of a published mathematical proof is an ambiguous process that requires multiple attacks and can take an unpredictable amount of time (not unlike proving something in the first place).

As a result, you must be selective about what proofs you decide to dig into, as the time commitment is potentially serious. In the study of algorithms (my field), for example, in most cases when reading a relevant paper it’s sufficient to dive down just deep enough to answer the following questions:

What is the main result and how does it compare to what was known before (or what a naive approach would provide)?

What is the high-level insight/trick deployed in the bound argument that enabled this improvement?

With experience, I’ve found that I can consistently produce this level of understanding within an hour (sometimes less if the paper is well-written or building on my own results).

This knowledge is not enough by itself to deploy or extend the technique presented in the paper, but it is enough to recognize future opportunities where this technique might be relevant to a problem you care about (at which point, you’ll have to dive deeper). In other words, maybe just one out of ten papers you read will end up proving directly useful to your own work, so it makes sense to learn just enough from the papers you read to identify whether or not they’re in that crucial 10%.

Idea #2: There are ways to be more efficient…

If you must understand the details of a proof, then in addition to the high-level suggestion from above of preparing yourself psychologically for a difficult battle, the following low-level strategies might also help:

Instead of trying to read through the proof linearly, build a hierarchy of dependencies among the lemmata and theorems. Summarize each lemma and theorem in your own words and summarize each dependency relation; e.g., how does this theorem use the following three lemmata? Once you have this map, it becomes clearer where to begin a deeper dive and provides context for what you’re reading.

(Last time I deployed this full proof-mapping process — which can be quite arduous — I ended up uncovering a flaw in a reasonably well-cited paper.)

In general, you should never start reverse-engineering a mathematical derivation until you understand what it is trying to show, why you expect it to be true, and how it will be used. If possible to assign some of this reverse engineering to a grad student, do so: it’s helpful to both parties.

Create your own system of notation and rewrite the relevant statements and re-derive the main results (or, rough approximations of the main results) using this notation. You’ll likely have to revise this notation system many times before you’re done, but this process will make it much easier for you to conceptualize the deeper insights of the argument.

(I had to do this last week for a proof that I needed to understand better. It took me something north of six hours to complete! But I do certainly understand better now what is going on underneath the covers of this particular line of thinking.)

Form reading groups with like-minded academics. Something about collaboration has a tendency to bust open mental road blocks and incite more creative thinking.

Idea #3: But perhaps the best strategy of all…

Get the authors on the phone or pull them aside at a conference and have them walk you through the argument. Nothing is more efficient than having the original author fill in the details of his or her thoughts.

(This latter strategy, of course, becomes more available as your status in your field grows. It might not be advisable, for example, for a first year PhD student to apply it with too much regularity!)

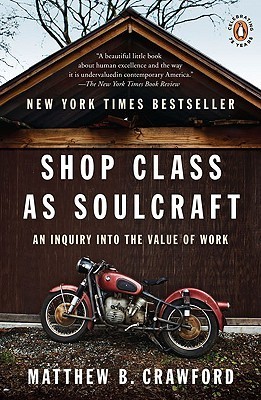

June 21, 2014

The Concrete Satisfaction of Deep Work

Deep Work as Soulcraft

Deep Work as Soulcraft

I recently reread Matthew Crawford’s 2009 book, Shop Class as Soulcraft. Though Crawford’s primary goal is to make a philosophical case for the skilled trades (think: Mike Rowe with footnotes), a lot of what he writes resonates with my thinking about deep work.

Consider the following quote, which caught my attention:

“The satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence have been known to make a man quiet and easy. They seem to relieve him of the felt need to offer chattering interpretations of himself to vindicate his worth. He can simply point: the building stands, the car now runs, the lights are on. Boasting is what a boy does, because he has no real effect in the world.” (page 15 of hardcover edition)

Cannot the same thing be said about any deep effort that results in the production of something too good to be ignored?

The reason, I think, that deep effort holds an appeal is that so much in modern knowledge work reduces to Crawford’s chattering interpretations — responding quickly to e-mail threads, bullet point self-promotion in PowerPoint slides, relentless online branding and ceaseless networking.

At some point, we tire of the shallow – necessary as it might be – and foster a desire to retreat into depth, create the best possible thing we’re capable of creating, then step back, point, and remark simply: “I did that.”

June 16, 2014

My Deliberate Quest to Read Proofs Faster

Deconstructing Theory

As a self-observant theoretician, I’ve learned that my research success depends on two intertwined factors: (1) my ability to digest and understand diverse results in my field; and (2) my ability to persistently attack good problems once identified.

Through practice over the past few years, I’ve become adept at the second factor. My deep work hours per week are quite high and have recently led to a correspondingly high rate of producing publishable results.

A nagging concern of mine, however, is that I’m not as good with the first factor. Indeed, I’m often frustrated with how long it takes me to digest interesting new results (and how often I end up aborting the process).

This concerns me because in my field voracious reading is required to keep the pipeline of good problems full.

What’s going wrong?

I’ve identified three issues that slow me down when reading existing work:

The results I read tend to be heavily mathematical but also appear in venues with space constraints. As a result, many details are missing. In a standard theory paper in my field it’s common to encounter a lot of (semi) complex inequalities that are just plopped down in the paper with minimal derivation or explanation, and then combined to achieve the proof. This style of mathematics by fiat makes it difficult to understand the argument and tends to overwhelm me.

Results are often expressed as a combination of text and math that can lead to ambiguity. (This morning, for example, I spent 90 minutes trying to understand the explanatory text that accompanied a frustratingly simple modular equivalence.) Often these ambiguities can be resolved in the larger context of the paper, but I have a tendency to remain where I get stuck, obsessing over the ambiguity until I get too tired to make any more progress.

I tend to lose my concentration faster when reading than when thinking. This occurs because understanding someone else’s result requires that you keep organized and accessible in your mind an ever growing collection of definitions and intermediate claims — many of which can seem arbitrary at first. This is tiring and I often flag too quickly to make productive headway.

To be clear, I’m not terrible at reading papers. As a professor, of course, I already do this activity at a high level as measured by most objective scales. But given my interest in continuing to push my abilities, I know that I could be even better.

Here’s my project: I want to overcome these issues and push my ability to quickly digest relevant academic papers to an extreme. This experiment is useful to me for obvious professional reasons, but I hope that it might also provide a nice case study in how such deliberate improvement proceeds in a knowledge work setting.

To get started on this project, however, I need some help. Please share in the comments if you have specific strategies you think I should consider…

June 5, 2014

Don’t Fight Distraction. Make It Irrelevant.

The War on Attention

My friend Dale (whose Ancient Wisdom Project blog you really should read) recently pointed me toward an interesting David Brooks column. In it, Brooks addresses the difficulty of maintaining focus in a distracted age:

And, like everyone else, I’ve nodded along with the prohibition sermons imploring me to limit my information diet. Stop multitasking! Turn off the devices at least once a week! And, like everyone else, these sermons have had no effect.

What’s interesting about this column is Brooks’ solution, which articulates a point that I firmly believe:

The lesson…then, is that if you want to win the war for attention, don’t try to say “no” to the trivial distractions you find on the information smorgasbord; try to say “yes” to the subject that arouses a terrifying longing, and let the terrifying longing crowd out everything else.

This rings true with my research on deep work. Those who are best at this skill are without exception obsessed with something that demands sustained attention, be it chess playing, writing, or theoretical physics. These deep workers rarely seem worried about distraction because it’s simply not an issue for them.

A New Focus on Focus

Distraction, from this perspective, is not the cause of problems in your work life, it’s a side effect. The real issue comes down to a question more important than whether or not you use Facebook too much: Are you striving to do something useful and do it so well that you cannot be ignored?

David Brooks would wager (and I would tend to agree) that once you can get to a positive answer to this question, you’ll find your worries about distraction rendered irrelevant.

###

I took the picture above in the woods near Georgetown where I like to go to churn on particularly knotty problems. As an interesting case study in the patience required for deep thinking, I originally posted the image back in January, where I talked about starting to work through an interesting but hard problem. Five months of persistent thought later, I finally finished the result. The deep life, it seems, is not a good fit for those who like immediate gratification!

May 28, 2014

Deep Habits: My Office in the Woods

Fashionably Deep

A reader sent me the above image. She implied that it represents a logical conclusion to my ever intensifying quest for depth.

I’m not there yet, but she’s not far off…

Case in point: I recently found a new hidden work location here on the Georgetown campus that I think trumps any previous spot I’ve found in terms of its ability to eliminate distraction and foster depth:

I hate to give away all my secrets, but the location of this particular spot involves the Glover park trail that abuts the western edge of the medical school.

###

As an unrelated logistical note, my good friend Ramit Sethi is holding a webinar to explain what the hell goes on in that fabled Dream Job course he offers. If you’re interested, I believe it’s tonight (Wednesday, 5/28). You can learn more here.

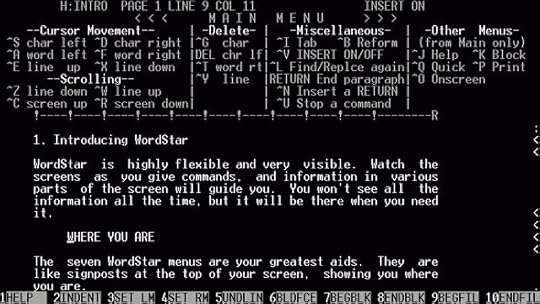

May 17, 2014

Should We Work Like Novelists?

The Habits of a Writer

As I continue to clear out my queue after my end-of-semester blogging hiatus, there’s another article to mention that recently caught my attention. The fantasy author George R. R. Martin, it turns out, writes his books using Word Star, an ancient word processor that runs on DOS (see the screenshot above).

“It does everything I want a word processing program to do and it doesn’t do anything else,” he explained.

Martin is not the only fiction writer with idiosyncratic rituals surrounding his work. Neil Gaiman, for example, famously does much of writing long hand, and Stephen King is very particular about his desk.

This interests me because fiction writers are the epitome of deep workers (to make any progress, fiction writing requires your full concentration), and many of them, like Martin, Gaiman, and King, seem to rely on unusual but well-honed habits to get them into this mindset.

A natural question arises from this observation: Should those of us who work deeply in other fields follow their example?

This has been on my mind recently. In my pursuit to improve my ability to work deeply, I’ve paid a lot of attention to issues like scheduling (e.g., blocks versus lists) and tracking (e.g., milestones versus hour tallies). Like many knowledge workers, however, I’m haphazard about the physical details that surround this work. I don’t have a special location or special tools I always use. I don’t have a head clearing ritual or hike to a hidden glen to tackle my knottiest problems.

But the more I hear about the habits of professional deep workers like novelists, the more I wonder if I should.

One of my goals this summer is to experiment more with the intensity piece of deep work (as I introduced in a recent blog post), and working with depth-inducing habits and rituals of the type described above should be part of this experimenting. With this in mind, if you’ve found any such behavior useful in your own (deep) work, let me know about it in the comments.

###

Unrelated note: My friend Laura Shin, who writes from Forbes.com, and has been nice enough to feature me in some of her articles, just published an ebook, The Millennial Game Plan, which collects the best of her writing. She touches on a lot of issues we like to discuss here.

May 16, 2014

Why Didn’t Dan Kois Quit Facebook?

The Facebook Cleanse

The Facebook Cleanse

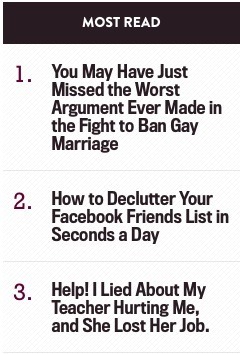

Earlier today, one of the most read articles on Slate was titled “The Facebook Cleanse.” It was authored by Dan Kois, a veteran writer who reviews books for Slate and contributes regularly to the New York Times Magazine.

The article opens with the following:

“For years, I’d been frustrated that Facebook felt completely useless to me. The signal-to-noise ratio was way too low…my feed was overwhelmed by randos: publicists I’d met at parties years before, comedians with whom I’d shared stages in 2004, siblings of high school classmates, readers I’d friended or accepted friend requests from in hopes of Building My Brand.”

At this point in the article, I hoped (fruitlessly) that Kois would then reach the following eminently reasonable conclusion:

“Then I realized that I was a grown man and a serious writer and the fact that I was devoting any thought to this weird, juvenile ad network cooked up by a twenty-year old was ridiculous, so I of course quit.”

Alas: I know better.

Kois instead detailed an elaborate and time consuming routine in which he carefully culled, over many days, his “friend” list down to something that felt less useless.

Sigh.

Here’s the thing: I don’t find social media worthless, but I’m floored by its universality.

It’s not surprising, in other words, that lots of people like Facebook, but it is surprising that there are so few people who don’t.

Neil Postman warned about this in his insightful (but somewhat overlooked) 1992 book, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. The danger is not when a given technology tries to take over our culture, he warns, but instead when we stop debating the incursion and just assume it’s necessary.

(To be clear, I don’t know Kois, and suspect he probably has good reasons to use Facebook. I’m just using him an archetype to drive this discussion.)

April 20, 2014

Richard Feynman Didn’t Win a Nobel by Responding Promptly to E-mails

Feynman’s Faux Irresponsibility

Around 38 minutes into the above interview, the late physicist Richard Feynman describes an unorthodox strategy for defending deep work:

“To do real good physics work, you do need absolute solid lengths of time…it needs a lot of concentration…if you have a job administrating anything, you don’t have the time. So I have invented another myth for myself: that I’m irresponsible. I’m actively irresponsible. I tell everyone I don’t anything. If anyone asks me to be on a committee for admissions, ‘no,’ I tell them: I’m irresponsible.”

Feynman got away with this behavior because in research-oriented academia there’s a clear metric for judging merit: important publications. Feynman had a Nobel, so he didn’t have to be accessible.

There’s a lot that’s scary about having success and failure in your professional life reduce down to a small number of unambiguous metrics (this is something that academics share, improbably enough, with professional athletes).

But as Feynman’s example reminds us, there’s also something freeing about the clarity. If your professional value was objectively measured and clear, then you could more confidently sidestep actives that actively degrade your ability to do what you do well (think: constant connectivity, endless meetings, Power Point decks).

Put another way: if other knowledge work fields judged merit with the academic model, you’d probably find it a lot harder to get people to show up at your next project status meeting…even if you promised extra-fancy animations in your deck.

###

Hat Tip: Eric S.

April 8, 2014

Work Accomplished = Time Spent x Intensity

The Straight-A Method

In the early 2000′s, I was obsessed with study habits. The obsession began with my interest in performing well at Dartmouth, then eventually evolved into a (surprisingly popular) book.

Something I uncovered during this period is that high performing undergraduates, as a general rule, seem to internalize the following formula:

Work Accomplished = Time Spent x Intensity

This formula helps explain why some students can spend all night in the library and still struggle, while others never seem to crack a book but continually bust the curve. The time you spend “studying” is meaningless outside of the context of intensity. A small number of highly intense hours, for example, can potentially produce more results than a night of low-intensity highlighting.

(This is how I avoided all-nighters, for example, during my three year stretch of 4.0′s as an undergraduate.)

From Campus to Corporation

I’m mentioning this phenomenon because of the following observation:

The above formula applies to most cognitively demanding tasks.

In other words, intensity affects the productivity of a knowledge worker as much as it helps the GPA of a college student.

An idea that’s gripped my imagination recently is that we’ve significantly underestimated the magnitude of this reality in our professional lives (I absolutely include myself in this plural pronoun).

Optimizing your intensity, in other words, might be more than a minor enhancement to personal productivity; it might instead unlock absurd rates of production.

I’m still gathering my evidence for this conjecture, but what I’m finding so far intrigues me.

(Here’s a taste: I recently interviewed a writer who published 1.5 million words last year, all the while writing only around 3 hours a day, five days a week. His secret: he systematically increased his intensity levels during these sessions using fine-grained metrics, ascetic schedules/rules, and aggressive environment hacking. If you want to see him in action, check out his upcoming kickstarter project in which he plans to co-write a book publicly in 30 days.)

In the meantime, it’s an interesting thought experiment to consider your own level of workday intensity, and wonder what would be involved in taking 2 – 4 hours of your day, and engineering your life so as to optimize the intensity of your concentration during these periods. What changes would you have to make to how you manage your energy, environment, or processes? What results might it produce?

As I attempt to devise a more coherent understanding of intensity management, I’d be interested to hear your thoughts or experiences.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9950 followers