Cal Newport's Blog, page 43

October 27, 2015

Deep Habits: WorkingMemory.txt (The Most Important Productivity Tool You’ve Never Heard Of)

Productivity Problems

Here’s a typical scenario. Looking at your daily schedule, you see that you’re entering a period of time that’s not dedicated to deep work or a specific large shallow task.

This seems like a good opportunity to tackle some of the small tasks that accumulate in most knowledge work schedules (e.g., e-mails, planning, bills, looking up information, arranging meetings, filling out forms, etc).

Tackling these administrative blocks in an effective manner, however, can be elusive for most people — especially if you find yourself arriving at the office after a weekend, or a trip, or any other instance when an overwhelming number of obligations have been piling up, waiting to ambush you.

It’s easy to start such blocks with a reasonable plan, such as “let me answer some e-mails.” But this will soon generate many more new obligations than you can fit into your limited working memory at one time.

At this point, you might start lurching around, perhaps trying to knock off the new obligations as they arise (so you don’t forget them), then giving up on this goal as futile, then seeing even more urgent messages, and having those generate even more things that you can’t quite finish all at once, and then, the next thing you know, you look up after an hour of frenzied e-mailing and feel more overwhelmed than when you began!

Whew.

The solution to such scenarios, I will argue, is to augment your limited neuronal capacity with some digital help…

The WorkingMemory.txt File

A few years ago, I stumbled onto the strategy of using a simple plain text file to augment my working memory during attacks on my mounting obligations.

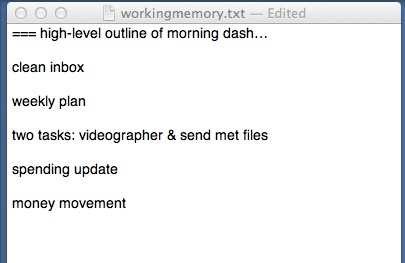

For obvious reasons, I named the file WorkingMemory.txt. Whenever I enter an administrative block, I open this file and place it next to my browser (see the screenshot above) so I can access it easily as I check my e-mail, review my calendar, or browse my task lists.

To understand the power of a simple text file in this scenario, let me walk you through a typical Monday morning administrative block from a few months ago…

The Initial Dump

The first thing I did in the block is simply dump in the WorkingMemory.txt file all the things I already knew I wanted to get done:

The first two items are what I always tackle at the beginning of the week, while the other three items just popped to mind as things that seemed time sensitive.

Capturing New Obligations

I then began reading and responding to e-mails — the first item on the list. As I dived deeper into my inbox, many new obligations were generated at a fast rate. I didn’t have time to accomplish each new obligation as I encountered it, and (this is the important part) I didn’t have nearly enough working memory in my brain to remember them all, so I jotted them all down in my trusty text file:

You might counter that I should have carefully processed each of these new obligations into a clear next action and then listed them under the appropriate contexts in my well-maintained tasks lists (as recommended by David Allen).

But I wasn’t ready to put in that amount of effort yet.

At this point, I’m capturing things in a stream of conscious style as they pop up. I can figure out what they mean later: for now, I just want them captured in my digital memory so I can get through all the e-mails in my inbox quickly without worrying about forgetting things.

The Clarification

After I finished with my inbox, I was ready to make sense of what was now on my plate. It’s at this point that I began to manipulate and clarify the information stored in my WorkingMemory.txt file:

There are several things to notice here. The first is that I extracted a clear task list for the remainder of the morning dash, dividing the tasks between “large things” (more than 5 minutes) and “small things” (less than 5 minutes).

I also went through and organized the rest of the information dumped into the file. You can see, for example, that under “to capture in system” I have the full list of things that I need to transfer to my task lists for later treatment.

Notice, also, that under “to include in weekly plan” I have identified a subset of those items that I want to include in the weekly plan I’m going to construct as part of this morning dash (see the “large things” list).

At this point in my morning, my inbox is empty and my mind is 100% clear. Everything I need to do or know is captured and clarified in my WorkingMemory.txt file — allowing me to devote my full energy to executing.

Big Picture

A lot of the details of the above example were specific to my preferences and the demands of that particular morning. If you watched my WorkingMemory.txt file over a period of several weeks, you’d see a wide variety of creative uses.

But the general strategy behind this tool remains the same: use a simple text file to capture, organize, and ultimately clarify all relevant information during administrative blocks — leaving your brain free to execute.

It’s amazing how much more efficient you become when you’re not clogging up your brain’s working memory with open loops and unresolved obligations.

October 21, 2015

The Power of the Outdoor Office

The Weirdo in the Woods

I took this picture last week. While most people enter the woods with a hiking stick, or perhaps a dog, I was the weirdo carrying a cup of coffee and a notebook.

But I was stuck on some early stage problems and needed some serious deep thinking to try to shake things loose — so I grabbed the tools of my trade and headed into the wilderness.

After about a half hour of walking and thinking, I stopped here to organize and record my thoughts:

By the time I finished my meander, I had broken through my log jam. Ever since, I’ve been scrambling to catch up with the thoughts this unleashed.

The Outside Office

There’s a surprising power to retreating to an outside office when there is serious thinking to be done.

Part of this power comes from the lack of interruptions. I brought my phone to take these photos, but usually I wouldn’t, which means any attempt to steal my time and attention at my outside office would require hiking boots.

But an equally important part comes from the setting. Nature has a way of filling your senses without demanding your attention (c.f., research on attention restoration theory), which, when combined with the act of walking, behaves like a performance enhancing drug for deep work.

These experiences reinforce my belief that for professions that require creativity, our notion of what constitutes an “office” is one that can and should be productively expanded.

October 19, 2015

Top Performer is Now Open

After Three Long Years of Development…

As I mentioned last week, I’ve spent the last three years working with Scott Young and his education company to develop an online course called Top Performer. The course picks up where SO GOOD leaves off, providing a systematic curriculum for:

identifying the skills that matter most in your profession;

constructing a deliberate plan to improve them rapidly; and

finding the time in your already busy schedule to consistently make progress on this endeavor.

You can learn more about Top Performer at the course web site, which includes a detailed video walkthrough, curriculum information, frequently asked questions, testimonials, etc.

The key detail is that we’re only leaving the course sign-up open for this week. We will close down course registration on Friday October 23rd at Midnight (Pacific Time).

Outside of a brief reminder on Thursday, this is the last time I’m going to talk about Top Performer on this blog. It’s now back to our normally scheduled programming…

October 13, 2015

Join Me and Scott Young for a Live Conversation this Weekend

I’m trying something new this weekend: a live webinar, co-hosted with my friend and collaborator Scott Young.

During the first half of the event, we’ll be discussing ideas inspired by SO GOOD, including our personal experience with career capital, deliberate practice, and elite level productivity.

During the second half, we’ll explain more about this mysterious Top Performer online course that I’ve been hinting about recently. (I’ve spent the last three years developing this course with Scott for his online course company, so I’m excited to finally go public about the details.)

Key Details: The webinar will be held at 4 p.m. Eastern on Sunday. It is free and open to anyone. To sign up, just click on this link.

This should be interesting. Hope to see a lot of you there…

October 7, 2015

A Productivity Lesson from the Prison Debate Team that Defeated Harvard

The Underdog Debate

News broke wide earlier today about something unexpected that happened last month at a maximum security correctional facility near Dannemora, New York: a team of prisoners won a debate contest held against Harvard’s vaunted three-time national champion team.

As reported by the Washington Post, a twist that made this outcome even more unlikely is that the prisoner team completed their extensive preparation without access to the Internet.

They were forced instead to make formal requests to the prison administration for the books and articles they required, and to then wait for days — and sometimes even weeks — for approval.

The easy storyline here is that this underdog team triumphed despite the hardship of being less connected. While this description might be largely true, the Post’s reporting suggests that something more interesting might have also happened:

[I]t’s worth asking whether circumstance forced the prisoners to devise an approach — in which limited resources demanded sharper focus and more rigorous planning — that resulted in superior lines of argumentation.

This is an important point. Removing the prison team’s access to the Internet made their debate preparation harder, but because it forced them to focus without distraction on exactly what they wanted to say and how to say it best, it also produced better results.

Easy Versus Effective

I think this confusion is common in the professional world: we too often mistake the idea of making our working lives easier with making our work better. But these are two different things.

Slack makes life easier in the moment for computer programmers, but it also leads them to produce messy, distracted code.

General purpose e-mail addresses really simplify corporate communication, but the resulting inbox madness is burning out a whole generation of knowledge workers.

And so on.

I’m not trying to argue for something radical here, but am instead suggesting a subtle shift in mindset. Don’t just focus on what might become harder if you sidestep some new type of connectivity, but also ask what you might gain due to this adversity.

When it comes to digital work, in other words, easy is usually good, but sometimes harder is better.

#####

An Exciting Announcement

Given that this post is about how to master hard things effectively, I thought this might be a good opportunity to briefly mention something related that I’m really excited about.

Over the past three years, Scott Young and I have been developing an online course called Top Performer. This course teaches you how to identify the skills (e.g., career capital) in your career that matter the most, and then rapidly and massively improve them in a short amount of time by applying deliberate practice techniques.

We’re going to launch this course in a couple weeks. If you want to learn when the course opens, and answers to common questions, sign up for my e-mail newsletter (the form is at the top right of this page) where I’ll be sharing more details.

October 5, 2015

On Full Horizon Planning and the Under-Appreciated Power of Workflow Systems

The Missing System

Here’s something that baffles me: the fact that most companies don’t invest in helping their employees develop effective workflow systems.

(It’s probably worth taking a moment here for definitions: When I say “workflow system,” I mean a set of habits and tools used to organize what work you do and when you do it. And when I say “effective,” I’m referring to the amount of value you produce.)

Most people don’t dedicate much thought to such systems. The default, instead, is to run your day as a reaction to events and deadlines on your calendar, an inconsistently referenced task list, and, most of all, the flux coursing through your inbox.

As productivity nerds know, however, there are much more effective ways to get important things done.

Full Horizon Planning

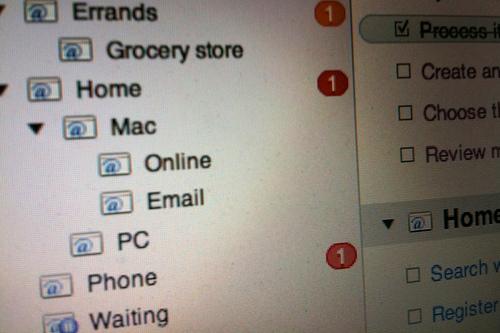

Consider my own workflow system (evolved over a decade of close scrutiny). I call it full horizon planning.

The motivating philosophy here is simple: every project I’m obligated to complete has two states, dormant or active; if it’s dormant, it’s tracked somewhere that is regularly reviewed (so I won’t forget), and once I make it active — and this is the important part — I make a plan for how and when the whole thing will be completed.

To pull this off, this plan must exist at multiple levels of refining granularity. That is, on the monthly level, I know what weeks I will work on the project, and only when I get to those weeks do I plan out what days I will work on it, and only when I get to the specific days do I figure out which hours it will consume.

(For specifics; c.f., here and here and here and here and here, among many relevant posts.)

These plans, of course, change as things unfold, but the point is that I don’t deal in abstractions, I like to work directly with the brute physicality of time. This makes sure I get the most out of the cycles I have available, and it prevents me from committing to more than is feasible.

This workflow system requires more upfront investment of mental energy than lurching from deadline to deadline, and it certainly wouldn’t work for all types of jobs, but it’s a major factor in my ability to consistently move ideas from conception to completion, and do so while rarely working past five.

To summarize, a good workflow system can (I suspect) at least double the amount of value the average employee produces. And yet, we rarely see much emphasis placed on optimizing this piece of the professional puzzle.

This smells like a big open opportunity to me.

September 28, 2015

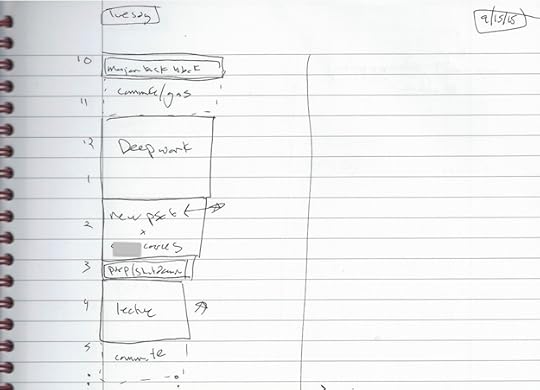

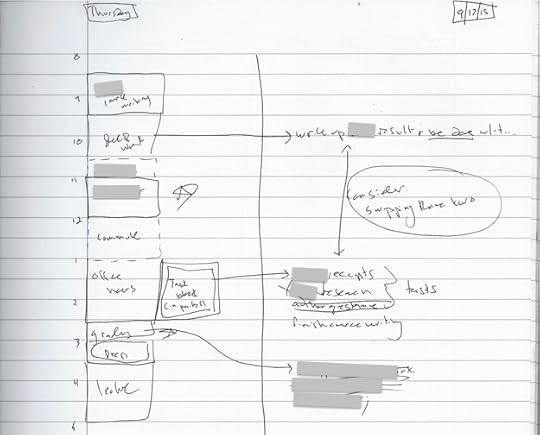

Deep Habits: Three Recent Daily Plans

A Blocking Believer

Longtime Study Hacks readers know I’m a proponent of planning in advance how you’re going to spend your time. To this end, each morning I block out the hours of my work day in one of my trusted Black n’ Red notebooks (see above), and assign specific efforts to these blocks.

My goal, of course, is not to make a rigid plan I must follow no matter what. Like most people, my schedule often shifts as the day unfolds. The key, instead, is to make sure that I am intentional about what I do with my time, and don’t allow myself to drift along in a haze of reactive, inbox-driven busyness tempered with mindless surfing.

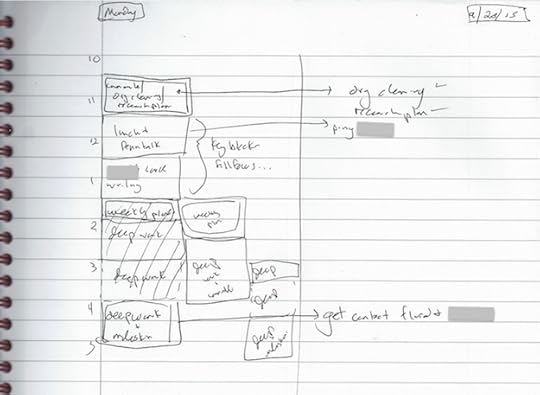

Though the basic idea behind daily planning is simple — block out the hours of the day and assign work to these blocks — many readers ask me good questions about the details of its implementation. In response to these queries, I thought it might be useful to show you a few of my actual daily plans from recent days during this past month…

The Triple Rewrite

Notice, this plan doesn’t start until 10:30. This doesn’t mean that I started work at 10:30. On many days, I like to dive right into a deep task for an hour or so before taking the time to make a plan for the rest of the day.

The columns growing to the right side are rewrites that I made throughout the day as my plan changed. Someone stopped by my office during the 12:30 block to discuss a research problem, which shifted the length of my 1:30 task block. But even that shift was not enough as that block ended up lasting until 3 — requiring yet another rewrite of the plan.

Also, notice how I use the right hand side to elaborate the details of some of my blocks.

A Well-Oiled Teaching Day

Here’s an example of a teaching day unfolding efficiently. After an early morning block of work (not captured on the plan), I batched some key tasks before commuting to work. I then immediately carved out two hours of deep work before turning my attention to updating the problem set I needed to post that day. From 3 to 3:30 I reviewed my course notes and did a final shutdown pass before heading to teach my 3:30 class.

Notice, an implication of this schedule is that between 10:30 and 3:00 I never saw my e-mail inbox.

Salvaging A Fractured Day

I actually wrote this Thursday plan the night before, so you can see the whole day laid out. Like most mornings, I start work at 8:30. In this case, I dived straight into a difficult course related task before turning my attention to deep work (which, for me, is almost always code for “working on research problems”).

The grayed out blocks that follow involve me taking my youngest son to a doctor’s appointment — a disruptive task from a scheduling perspective. But notice how my use of daily planning allows me to salvage every ounce of productivity from the day. Not only did I get a lot done before I left, but on arriving at campus, I was ready to inline core tasks into the down periods that arose during my regularly scheduled office hours.

I then had a grader’s meeting and some final preparation for my lecture before heading off to teach.

On the right hand side you’ll see an elaboration of what tasks I planned to complete during my task block as well as a suggestion that I might consider swapping the deep work block with the task block (in the end, I didn’t).

A Few Closing Notes

My goal in showing the above examples is to demonstrate the mundane reality of daily planning. It’s not a super secret system, and it can be messy (especially if your handwriting is as bad as mine), but it’s still absurdly effective at insuring that at the end of each week you look back and are proud of what you accomplished.

September 15, 2015

Alexandra Pelosi is Not Buying What Silicon Valley is Selling

Pelosi’s Anti-Social Confession

Alexandra Pelosi falls within a prime professional demographic for social media use.

She makes documentary films on topical issues, dabbles in activism, and is a frequent TV commentator.

She lives in New York and grew up in San Francisco (which her mom, Nancy Pelosi, famously represents in Congress).

She wears ironic, black-framed nerd glasses.

But if you want to friend her on Facebook or browse her tweets you’re out of luck. Here’s Pelosi talking last Friday on the Overtime segment of Bill Maher’s HBO show (10:35 in the above clip):

“I’m not on Facebook, I’m not on Twitter, I’m not buying into the whole thing…”

Pelosi’s lack of interest in social media has seemingly done little to slow down her successful career as a filmmaker. This, I think, is important to point out because it underscores a reality worth repeating again and again: nothing bad happens if you don’t buy into every venture-backed attention snare that comes out of the San Francisco peninsula.

On the other hand, such skepticism probably does generate good outcomes, such as the time and space needed to create .

September 7, 2015

How Louis C. K. Became Funny and Why it Matters

Louis C. K.’s Plateau

A reader recently sent me the above video of comedian Louis C. K. speaking at a 2010 memorial to George Carlin. His brief remarks provide interesting insight into the reality of how people reach elite levels in their fields — and why it’s so rare.

As C. K. begins, when he first attempted comedy, he was, like most new comedians, terrible. But he wasn’t deterred:

“I wanted it so bad, that I kept trying, and I learned how to write jokes.”

This early burst of effort helped C. K. become a professional, with a full hour’s worth of reasonable material.

It was here, however, that he stalled. For a long time…

“About fifteen years later, I had been going in a circle that didn’t take me anywhere. Nobody gave a shit who I was, and I didn’t either, I honestly didn’t. I used to hear my act, and go, ‘this is shit and I hate it.'”

This is the lesser told story about the quest for elite accomplishment. It’s common to hear about the exciting initial phase where you’re terrible but motivated and therefore see quick returns.

But so many people, like C. K., soon hit a plateau. They’re no longer bad. But they’re also not improving; stuck in a circle that doesn’t take them anywhere.

Inviting the Awful

What makes this Louis C. K. clip interesting, however, is that he goes on to explain how he broke out of the circle of mediocrity that was trapping him.

This escape began when C. K. heard an interview with George Carlin. In this interview, Carlin said his method was to record one comedy special each year. The day after he was done recording, he’d throw out his material and start over.

At first, C. K. was incredulous, thinking:

“That’s crazy, how do you throw away…it took me fifteen years to build this shitty hour.”

But he soon realized something: Carlin’s sets got better each year.

The reason: writing material from scratch is a brutally effective form of deliberate practice. It forces you to seek out new topics and dive deeper and approach fresh what you think is funny and not funny.

It’s the essential process that makes you better as a comedian, and C. K. had been avoiding it for the past decade and a half.

Feeling “desperate” with nothing left to lose, C. K. adopted Carlin’s strategy by throwing out his material and committing to write something new each year: a process which he latter dubbed, to “invite the awful” — a reference to the difficulty of starting something hard from scratch.

The results were astounding.

C. K. spent fifteen years stuck as a nobody comic with a “shitty set,” but after only four years of applying the Carlin strategy, Comedy Central named him one of the 100 funniest stand-ups of all time.

This is a lesson I need to remind myself of on a regular basis. Getting started on the path to craftsmanship is hard. But it’s equally important (and hard) that you keep inviting the awful by pushing yourself to new places and new levels of ability.

If it’s easy to do, you’re not getting better.

September 2, 2015

Digital Sabbaticals Don’t Make Sense

The Digital Sabbatical

The idea of a “digital sabbatical” is relatively recent: the earliest traces I can find date to 2008 (e.g., this dated gem from CNN). Its popularity, however, has skyrocketed since then.

The mechanics of a digital sabbatical are simple: you set aside a period of time — typically on the scale of days — where you refrain from using some subset of your standard digital network tools.

Many reasons are given for these sabbaticals. Some seem contrived, like boosting creativity or losing weight, but most people understand the real appeal of this behavior: their digital lives consume and ultimately exhaust them, and they crave a break.

As Pico Iyer put it: “It’s only by having some distance from the world that you can see it whole.”

To me, however, this idea never quite made sense.

An Odd Standard

To understand my confusion, try applying the logic of a digital sabbatical to any other behavior that’s addictive and exhausting and drives people to want to escape.

For example…

Imagine advising someone who is overweight due to massive overeating of unhealthy food that they need to take a week every year where they eat healthily.

Imagine telling someone with a terrible cigarette addiction that the solution to their problem is that they need to give up smoking on Sundays.

Imagine telling someone who feels weak and lethargic that once every few years they need to retreat to a hermitage to spend a month exercising.

My point is that for most any other behavior that lures you in with positive attributes, but then takes over your life and drives you to exhaustion, our standard response is that you need to radically and permanently reduce or eliminate that behavior.

The same could and should apply to the world of the digital.

As George Packer quipped in an under-appreciated New Yorker essay: “[Twitter] scares me, not because I’m morally superior to it, but because I don’t think I could handle it. I’m afraid I’d end up letting my son go hungry.”

What is it about digital addictions that make us think the occasional break will suffice?

(Photo by Hartwig HKD)

#####

Longtime readers know I’ve been a big fan of Geoff Colvin since his paradigm-shifting 2008 book, Talent is Overrated. I recently finished reading a review copy of his latest title, Humans are Underrated. I was riveted. If you’re interested in remaining valuable in an increasingly automated and high-tech economy, take a look at this book.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers