Woody Allen and the Art of Value Productivity

A Tale of Two Productivities

As a graduate student I was known for being organized. I was reminded of this a couple weeks ago when I attended a computer science conference along with many of my old lab mates.

What I also remember is that I always felt indifferent about this reputation. To be organized is a nice thing. But it didn’t take me long at MIT before I realized it’s also unrelated to what matters most: the consistent production of high value results.

We don’t often talk about this division but I think it’s crucial. There’s a lot written about task productivity (the ability to organize and execute non-skilled obligations), but much less written about value productivity (the ability to consistently produce highly-skilled, highly-valued output).

As I’ve settled more into life as a professor, I’ve been increasingly fascinated with value productivity. It’s not that task productivity lacks importance — it has saved me much stress — but I think the value variety is what will rule in an increasingly competitive knowledge economy.

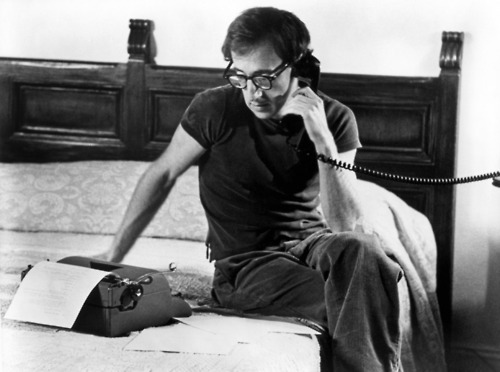

It is with this fascination in mind that I spent some time recently re-watching Robert Weide’s deep diving documentary on the life and habits of Woody Allen. When it comes to value productivity, Allen is an unquestionably good place to start. He’s written and directed 44 movies in 44 years, earning 23 Academy Award nominations along the way.

By watching the documentary with an ear for work habits, I picked up the following three ideas that help explain Allen’s astonishingly high level of value productivity…

Idea #1: Don’t Break the Chain

One of Allen’s best known habits is that he writes every day for a fixed amount of time. As he explained: “If you work only three to five hours a day you become very productive. It’s the steadiness of it that counts. Getting to the typewriter every day is what makes productivity.”

The flip side of this commitment is that he feels no guilt relaxing once he hits his daily quota.

Seinfeld calls this the “don’t break the chain” strategy — and it has a large following. In the past, I’ve been skeptical of such rigidity. Allen, however, might be converting me to this point of view; at least, for certain types of work, namely non-urgent, high value projects.

Here’s why: It’s easy to convince yourself that these projects have a high priority in your life while at the same time you commit a shockingly small amount of time toward their completion. This is a recipe for self-delusion or self-despisal (when you realize how little is getting done).

Allen’s approach solves both problems.

Idea #2: Be Bold in Conception, But Pragmatic in Execution

Allen is often bold in conceiving a project. Once he starts executing, however, his focus turns to doing whatever it takes to ship a finished product on budget and on time.

“You always set out trying to make Citizen Kane,” he famously quipped. “By the time you get to the editing room, you try just not to be humiliated.”

(This reminds me a lot of the publishing process. My books are always ground breaking. Then I have to write them.)

Allen’s balance is critical because it’s easy to fall too far to one side or the other. If you just ship for the sake of shipping, for example, you’re likely to end up producing an ever-growing mountain of mediocrity. You must, in other words, push yourself to do something better. At the same time, if you become too entangled in your own hype, you’re likely to fall into perfectionism — letting years worth of opportunities pass as you ponder your masterpiece.

Idea #3: Focus on High Return Activities, Not Twitter

Early in his career, Allen identified what activities generated the highest returns, and then focused relentlessly on these behaviors to the exclusion of most other distractions.

He writes scripts, for example, freehand in a home office on yellow notepads. Once the idea begins to gel he types a polished version on an Olympia SM-3 manual typewriter — the same machine he bought as a teenager when he first began writing gag lines for newspaper columnists.

By stripping down his work hours to the core elements, and removing from his life the often insidious question of “what should I do next?”, he’s able to extract a huge amount of value from the limited hours he spends each day writing.

But what about social media you ask? Certainly an entertainment personality needs a following online! Allen (and his 23 Academy Award nominations) disagrees. Forget Twitter, he’s never owned a computer.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers