Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 9

August 9, 2015

Truthiness, scienciness, and product success

By Gordon Rugg

This is a Tempest Prognosticator.

“Tempest Prognosticator” by Badobadop – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tempest_Prognosticator.jpg#/media/File:Tempest_Prognosticator.jpg

“Tempest Prognosticator” by Badobadop – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tempest_Prognosticator.jpg#/media/File:Tempest_Prognosticator.jpg

It’s a splendid example of nineteenth century ingenuity, right down to the name. What does it do? It’s intended to let you know if a storm is approaching. The way it does this is as wonderfully nineteenth century as the name. The Prognosticator is operated by twelve leeches, each of which lives in a bottle. When storms are approaching, the leeches become agitated, and climb out of the bottle. When they climb out, they disturb a piece of whalebone, which activates a bell. The more serious the risk of storm, the more leeches climb out, and the more bells ring.

When it was invented, in the 1850s, the British government were looking for better systems of weather forecasting. They were particularly interested in predicting storms, which were a major threat to sail-powered ships.

So, did they adopt the Tempest Prognosticator as their preferred solution to this problem? As you might have guessed, they didn’t. Instead, they opted for the FitzRoy’s Storm Glass.

“Storm Glass FitzRoy Sturmglas” by ReneBNRW – Own work<<https://commons.wikimedia.o/wiki/File:Storm_Glass_FitzRoy_Sturmglas.JPG#/media/File:Storm_Glass_FitzRoy_Sturmglas.JPG

“Storm Glass FitzRoy Sturmglas” by ReneBNRW – Own work<<https://commons.wikimedia.o/wiki/File:Storm_Glass_FitzRoy_Sturmglas.JPG#/media/File:Storm_Glass_FitzRoy_Sturmglas.JPG

The Storm Glass also had a wonderfully nineteenth century name, but it worked on a very different principle. (In fairness, almost anything would work on a different principle from leech power…)

The Storm Glass was a glass that contained liquid, with chemicals dissolved in the liquid. Different versions of the glass used different ingredients, but the core concept was the same. The contents of the glass were sensitive to weather conditions, and showed different levels of crystal formation within the glass, depending on the weather.

The British government adopted this device as the preferred form of storm warning, and distributed storm glasses to a number of coastal towns in 1859, when there was a spate of violent storms.

And there the story would end, if you were just looking for examples of Victorian eccentricity. If, however, you’re looking for the underlying factors in designing successful new products, there’s a lot more story to tell, and the full version of the story has some powerful implications.

The bottom line

For a start, there’s the awkward consideration that the Storm Glass didn’t actually perform at above chance levels in predicting storms. The crystallisation rates correlated with temperature, but not with impending storms. In short, it didn’t work.

Nobody knows for sure whether or not the Tempest Prognosticator actually could predict storms, but its underlying assumption is far from silly; various types of animal are sensitive to weather conditions. The Tempest Prognosticator might quite possibly have worked.

What was going on?

It might seem reasonable to assume that when lives are at stake, people will check whether or not the relevant technology actually works. Reasonable, yes. True, no. Surprisingly often, technologies are widely adopted even though they either don’t work at all, or make things worse.

In an ideal world, people would check the relevant evidence thoroughly and systematically. However, it’s not an ideal world. One simple, powerful issue is lack of time. There isn’t enough time to check all the evidence that relates to every decision that you make.

Instead, human beings use a lot of heuristics – rules of thumb that don’t always work, but that work often enough and swiftly enough to let you make reasonably good decisions reasonably often.

That was probably a major factor in the British government’s decision to adopt the FitzRoy Storm Glass. FitzRoy wasn’t just anybody; he was Vice Admiral Robert FitzRoy, RN. He was the FitzRoy who commanded the Beagle during Darwin’s famous journey; he was the FitzRoy who set up the first incarnation of the Meteorological Office in 1854; he was the FitzRoy who was Governor of New Zealand from 1843 to 1845.

That’s a pretty strong portfolio.

In contrast, the Tempest Prognosticator’s inventor, Dr Merryweather, was honorary curator of the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society’s Museum. That doesn’t inspire so much confidence. Also, his invention was inspired by a couple of lines of poetry about a leech rising in his prison; again, this isn’t the strongest of arguments for adopting his technology.

When you look at the bigger picture, you soon discover that FitzRoy’s poor performance with the Storm Glass was an exception, rather than a rule. Other devices that he invented or improved, such as various forms of barometer, were a lot more successful, and many of his innovations are still in use today. So, overall, the heuristic of choosing the candidate with the stronger relevant track record actually performed reasonably well in the broader context, and just came off the rails with the one example of the Storm Glass.

Truthiness, scienciness and covering your back

Looking at track records is one heuristic for swiftly getting a rough idea of how much to trust an idea.

Another heuristic is to look at the language being used to describe it. This is rich ground for charlatans, many of whom play to this heuristic by describing their wares using words that look scientific, and stories that appear to have the ring of truth. The terms “scienciness” and “truthiness” were invented to describe this phenomenon. It’s depressingly widespread.

Another factor that is probably at play in the story of the Tempest Prognosticator is the simple principle of covering your back if you’re a bureaucrat making a decision. There used to be a saying that nobody ever got fired for buying IBM. Similarly, a civil servant probably wouldn’t get fired for selecting a Storm Glass invented by Vice Admiral Robert FitzRoy, RN, Meteorological Statist to the Board of Trade. Selecting a leech-powered device invented by a museum curator, inspired by two lines of poetry, wouldn’t be such a good career decision.

So, at one level, this story makes good sense.

At another level, though, there’s the nagging question of whether the Tempest Prognosticator actually worked.

I’m fascinated by the faulty assumptions made at key decision points in science. When the Tempest Prognosticator was pitted against the Storm Glass, science was making huge progress in chemistry. The Storm Glass fitted comfortably within the schema of chemistry being the way of the future. The Tempest Prognosticator, in contrast, was based on leeches, which had associations with an older, unscientific world. The Tempest Prognosticator was on weak ground with regard to the heuristic of “Modern is better than old”.

As far as I know, the Tempest Prognosticator was never systematically evaluated in terms of how well it actually worked. Instead, it appears to have been rejected on the basis of heuristics. The history of science is littered with tantalising examples of innovations which were ignored for decades or centuries because of similar decisions, but which turned out to have been right all along.

Having said which, honesty compels me to admit that I don’t have any plans to acquire a Tempest Prognosticator in the foreseeable future. Sometimes, heuristics end up with a sensible conclusion, even if the way they got there was a bit dodgy…

July 24, 2015

200 posts and counting

By Gordon Rugg

Our earliest posts included a lot of tutorial articles about specific concepts and methods, such as graph theory and card sorts.

Our more recent posts have increasingly often featured broader overviews, and demonstrations of how concepts and methods can be combined. This has included a fair amount of material on academic craft skills, where we’ve looked systematically at how to turn abstract academic concepts such as “good writing” into specific detail.

We’re planning to continue this move towards the bigger picture in our posts over the coming year. We’ll look at how formalisms from knowledge modelling can make sense of a range of features of society, including belief systems and organisational systems.

On a more prosaic level, we’ll continue our tradition of offbeat humorous articles.

In that tradition, the closing part of today’s article is this inimitable quote; we hope it brightens your day.

“I don’t play a lot of tuba anymore. It’s not the most common or useful instrument. There’s a reason there’s not a lot of tuba in a heavy rock and roll band. I’m just glad I was able to use it to help people,” he says.

“At the end of the day, I was just at the right place at the right time with a sousaphone.”

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/07/22/meet-the-man-who-beat-the-kkk-with-a-tuba.html

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this blog in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

July 17, 2015

Death, Tarot, Rorschach, scripts, and why economies crash

By Gordon Rugg

The best examples of powerful principles often come from unexpected places.

Today’s article is one of those cases. It’s about why it often makes excellent sense to use a particular method, even when you’re fully aware that the method doesn’t work as advertised on the box, or doesn’t work at all.

It’s a story that starts with one of the most widely misunderstood cards in the Tarot pack. The story also features some old friends, in the form of game theory, pattern matching and script theory. It ends, I hope, with a richer understanding of why human behaviour often makes much more sense when you look at the deep underlying regularities, rather than at the surface appearances.

So, we’ll start with Tarot cards. A surprisingly high proportion of people who use Tarot packs will cheerfully tell you that the cards have no mystical powers. Why would anyone use Tarot cards if they don’t have those powers? There are actually some very good reasons.

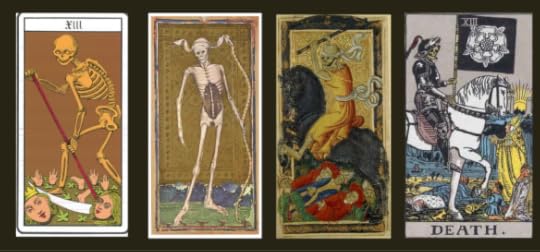

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

One major reason for using the Tarot even if you don’t believe it has any supernatural powers is that it can be a very good way of helping people to re-assess their lives, and how they are handling the issues in their lives. (Standard disclaimer: There are numerous different views of the Tarot, and I’m giving a short, simple version in the interest of keeping this article to a manageable length.)

The Death card is a good starting place. It’s a usual suspect in B movies, as an omen of very bad things about to happen. Its appearance is usually the cue for some extreme over-acting and some very loud dramatic music, with perhaps a thunderclap thrown in for good measure. In most Tarot readings, though, it’s treated very differently. Terry Pratchett did an excellent job of illustrating this issue via his much-loved character Death in the Discworld novels. In both traditional Tarot and the Discworld, Death isn’t the end of everything; instead, Death is a change. Sometimes that change is for the worse, but often, it’s a change for the better, the loss of dead wood so that new shoots can grow.

This perception can be extremely useful for people who are going through stressful times, and who have been focusing only on what they might lose, as if it were the end of the world. In this situation, the Tarot card can be a useful way of reminding people that there’s more than one way of interpreting what’s happening, and of breaking them out of the obsessive fearful focus on potential loss. It can do that perfectly well without any need for invoking mystical powers, which is why so many users of the Tarot don’t believe that there is anything supernatural involved, but still find it useful.

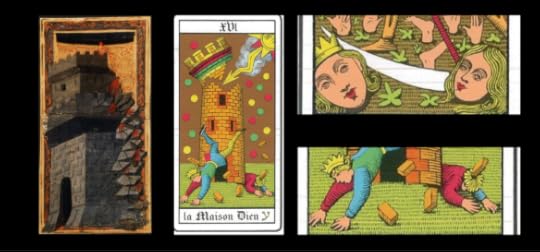

Here’s an example of how that insight is designed into the cards. The two cards on the left show the Tower, which symbolises destruction and loss. The two cropped images on the right show details of the faces in the Death card (upper image) and the Tower card (lower image). The faces from the Death card look calm and unconcerned; the faces from the Tower card don’t. The symbolism extends further; Death is usually shown carrying a scythe, a tool normally used for harvesting, as part of the timeless cycle of death and re-growth.

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

This explains why the Tarot’s depiction of Death can help people to re-perceive their situation more constructively. However, it raises a new question, namely how the image of nihilistic destruction in the Tower can help people.

Again, the answer lies in broadening the context. The Tarot card is traditionally divided into two sets, known as the Major Arcana and the Minor Arcana. The Minor Arcana is very similar to everyday playing cards, with four suits (Clubs, Coins, Swords and Staves) each of ten numbered cards plus four court or face cards (King, Queen, Knight and Jack/Knave). The Major Arcana usually consists of 22 cards, which are each unique (i.e. they don’t belong to suits).

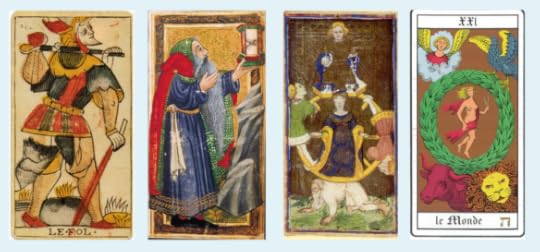

One traditional use of the Major Arcana is to symbolise life as a whole. The cards below show four classic examples of this.

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

The first card in this image is the Fool, setting off on life’s journey. The second is the Hermit, on a lonely journey through the wilderness in search of understanding. The third is the Wheel of Fortune, showing how fate can cast down a king, and raise up a beggar. The fourth is the World, which contains repeated symbolism about underlying unity beneath surface appearances.

In this broader context, the Tower is part of a much bigger whole. It may not bring re-growth and better things in its wake, but it’s not the end of the world, and it is part of gaining a deeper and richer understanding of the world.

What’s going on under the bonnet/hood?

That’s a brief description of how the Tarot can be useful for gaining broader and deeper insights into the situation that you’re going through. There’s a fairly consistent body of anecdotal evidence that it works reasonably well for this purpose. That raises the question of just how it works.

Rorschach and pattern recognition

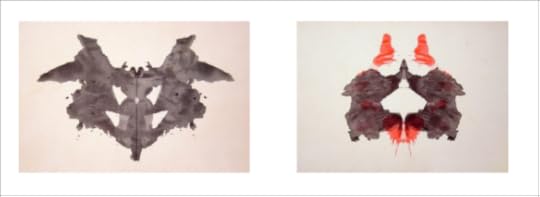

There’s a plausible argument that the Tarot pack can function as a form of Rorschach test, where people’s personal interpretations of an image give insights into how they view the world. This can be a useful starting point for understanding someone as part of a process of counselling.

Rorschach ink blots: Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Rorschach ink blots: Sources for images are given at the end of this article

In terms of processing mechanisms in the brain, it’s a classic example of pattern matching, which is a usual suspect when making sense of how people interpret objects and situations.

Script theory

This leads on to script theory and schema theory, which deal with people’s mental templates for actions and for organising their knowledge. Much of what is popularly lumped together as “wisdom” involves having a bigger mental toolbox of scripts and schemata than most people, so that you can draw on more possible ways of handling a given situation, or of making sense of a situation.

A classic example of how this can help is the advice to aim for a 75% rejection rate in your job interviews. At first glance, this looks like a really bad idea. When you look under the surface appearance, though, this schema makes excellent sense. If you’re getting a 100% success rate in terms of job offers, you’re aiming too low, and you could be applying for better jobs with a good chance of success. Conversely, if you’re getting a 100% rejection rate, you’re either aiming too high or you’re doing something wrong, so you need to change your aim and/or your application package.

That explanation makes sense as it stands. It makes even more sense when you dig deeper. The figure of 75% isn’t completely arbitrary. The classic recruitment process often ends up with a shortlist of about four candidates being interviewed, all of whom are appointable. Often, there’s hardly anything to choose between them, and the final choice hinges on some comparatively minor point. So, if you’re applying for jobs where you’re appointable, then by sheer chance you’re going to be offered the job about a quarter of the time, and not offered it about 75% of the time.

There’s another advantage to this schema. Psychologically, it turns a letter saying that you haven’t got the job from being a “rejection letter” into a data point that you will use to check that you’re broadly on track with your application process. That can be a huge boost to your morale, and to your feeling of control over your life. Instead of thinking in terms of a rejection letter being like the Tower in the Tarot pack, symbolising external forces causing pointless destruction and tragedy, you’re thinking of it as being part of a bigger, healthier whole, like Death being part of the cycle of change.

Game theory and graphology: When what’s bad for the system is good for the sub-system

So far, I’ve focused on how something that doesn’t work in one way can work very well in a different way. In a perfect world, I would stop at that point, with some nice, fluffy thoughts about kittens and trees and sunshine.

However, the world is not a perfect place, and most methods are open to abuse of one sort or another. In the case of Tarot, techniques such as cold reading and Barnum statements can be used by unscrupulous practitioners to give the impression of psychic powers, as a step towards bilking the unfortunate client out of money for promised services.

That form of abuse is fairly easy to spot, and to understand. A different form of abuse involves a subtler set of mechanisms, where something that looks irrational actually makes perfect sense when you unpack what’s really going on. It’s the cause of a lot of organisational problems, up to and including the various banking collapses and economic crises of the last few decades. It involves game theory and systems theory; the example that I’ll use to illustrate it involves graphology.

Back in the days of big hair and shoulder pads and companies with money to spare, quite a few companies used graphologists as part of the hiring process. Job applicants would be processed in the usual way, but the company would also pay a graphologist to study the handwriting of the applicants, and give opinions on each applicant’s character, as allegedly revealed in their handwriting.

Psychologists as a profession were not very amused by this, since the documented evidence showed pretty clearly that graphology was at best only slightly better than chance in assessing people’s characters; even back then, it was generally viewed by researchers as a pseudo-science. However, companies kept on using graphologists regardless. What was going on?

The answer, ironically, came from organisational psychology. Imagine that you’re one of the people hiring a new member of staff. You choose someone, and six months later they flee to the Bahamas with a large amount of loot pilfered from the company’s accounts. What does this say about your abilities to judge character, and about your prospects for promotion? Nothing good…

Now let’s imagine that you’re in the identical recruitment process, only this time you pay a graphologist to give their assessment of each candidate. The graphologist doesn’t say anything alarming about any of the candidates. You go ahead and hire someone, and six months later they do the “Bahamas with the loot” routine.

What happens now? What happens is that you immediately fire the graphologist, and hire one with a better reputation. The buck no longer stops with you; instead, it stops with the graphologist. From your point of view, this is a good strategy, and worth every penny that you pay the graphologists. From the company’s point of view, that money is going straight down the drain, but that’s not your problem, and if the company folds, you can always apply for jobs in another company.

In formal terms, this is a classic example of the principle from systems theory that subsystem optimisation does not necessarily lead to system optimisation. In terms of game theory, the payoffs to the employee from following the graphology approach are at the expense of the company.

This issue has been at the heart of various banking and economic disasters. When there are incentives for individual employees to work in a way that is bad for the organisation, there is going to be trouble. Often, those incentives aren’t intended by the organisation’s managers, but that’s not the point. The point is that the incentives are driving in a direction that is counter to what’s good for the organisation as a whole.

That’s bad enough when it’s just an individual bank involved. When it’s an entire sector, such as banking, or an entire economy, then words such as “catastrophe” and “disaster” come into their own.

Closing thoughts

In conclusion, sometimes things work for reasons different from the advertised reasons. This can be a good thing, or a bad thing, or a mixture.

In the case of Tarot, where this article started, the results can be useful in terms of helping people develop a richer and broader set of strategies for handling situations. The underlying philosophy of most schools of Tarot thought is very much about the bigger picture of morality; going beyond ignorance and selfishness into a deeper understanding of the world as a whole, and of our part in it.

In the case of incentives within banking and economics, the conceptual tools for fixing the problem have been available for decades. As for how to get those tools deployed by people with an incentive for making them work, though, that’s a separate question, for some future article…

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

There’s a reasonable overview of the Tarot here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarot

Banner images:

“13 – La Mort” by Oswald Wirth – Le Tarot. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:13_-_La_Mort.jpg#/media/File:13_-_La_Mort.jpg

“Visconti-Sforza tarot deck. Death” by Anonymous – Visconti-Sforza tarot deck. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Visconti-Sforza_tarot_deck._Death.jpg#/media/File:Visconti-Sforza_tarot_deck._Death.jpg

“Death tarot charles6″ by Unknown – http://expositions.bnf.fr/renais/arret/3/index.htm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Death_tarot_charles6.jpeg#/media/File:Death_tarot_charles6.jpeg

“RWS Tarot 13 Death” by Pamela Coleman Smith – a 1909 card scanned by Holly Voley (http://home.comcast.net/~vilex/) for the public domain, and retrieved from http://www.sacred-texts.com/tarot (see note on that page regarding source of images).. Via Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:RWS_Tarot_13_Death.jpg#/media/File:RWS_Tarot_13_Death.jpg

Tower images:

“Maison-Dieu tarot charles6″ by Unknown – http://expositions.bnf.fr/renais/arret/3/index.htm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maison-Dieu_tarot_charles6.jpg#/media/File:Maison-Dieu_tarot_charles6.jpg

“16 – La Maison de Dieu” by Oswald Wirth – Le Tarot. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:16_-_La_Maison_de_Dieu.jpg#/media/File:16_-_La_Maison_de_Dieu.jpg

Life journey images:

“Hermit tarot charles6″ by Unknown – http://expositions.bnf.fr/renais/arret/3/index.htm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hermit_tarot_charles6.jpg#/media/File:Hermit_tarot_charles6.jpg

“Sforzawheel” by B.Bembo? – http://www.tarothistory.com/viscontisforza.html. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sforzawheel.jpg#/media/File:Sforzawheel.jpg

“21 – Le Monde” by Oswald Wirth – Le Tarot. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:21_-_Le_Monde.jpg#/media/File:21_-_Le_Monde.jpg

“Jean Dodal Tarot trump Fool” by Original uploader was Fuzzypeg at en.wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Jerome Charles Potts using CommonsHelper.. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_Dodal_Tarot_trump_Fool.jpg#/media/File:Jean_Dodal_Tarot_trump_Fool.jpg

Rorschach images:

“Rorschach blot 01″ by Hermann Rorschach (died 1922) – http://www.pasarelrorschach.com/en/inkblots.htm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rorschach_blot_01.jpg#/media/File:Rorschach_blot_01.jpg

“Rorschach blot 02″ by “Hermann Rorschach” (died 1922) – http://www.pasarelrorschach.com/en/inkblots.htm. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rorschach_blot_02.jpg#/media/File:Rorschach_blot_02.jpg

July 9, 2015

The 28 versions of the Golden Age

By Gordon Rugg

The idea of a Golden Age has been around for a while, in one form or another.

How many forms? There’s a good argument for there being 28 forms.

Why 28? That’s what this article is about. I’ll look not only at the idea of the Golden Age, but also at some of the related issues which ripple out from it, including archetypal plots in fiction, history and politics.

Gold, silver and bronze from the Classical Age

Details of the image sources are given at the end of this article

Details of the image sources are given at the end of this article

As usual, the story involves Ancient Greek philosophers getting things partially right, and causing confusion that lasted for millennia. It also includes mystical German philosophers contributing their particular type of chaos to the mix. Fortunately, and with a neat symmetry, it also includes Ancient Greek historians and rationalist German philosophers taking a much more insightful and useful view of the issues.

Plato is a prominent figure in the early stages of the story. He subscribed to the view that there was an early Golden Age, when everything was quite wonderful, and that subsequent ages involved a steady decline, which is set to continue for the future. It’s essentially the “When I were a lad” view of life, dressed up in impressive words.

Hegel, and various other philosophers, on the other hand, took the view that things were getting steadily better, from rough and bad early days towards a mystically ideal future. It’s essentially the “Every day, in every way, we are getting better and better” view of life, dressed up in words so vague and impressive-sounding that he made a good career out of them.

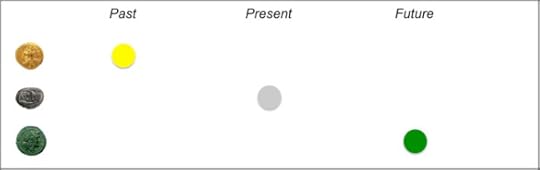

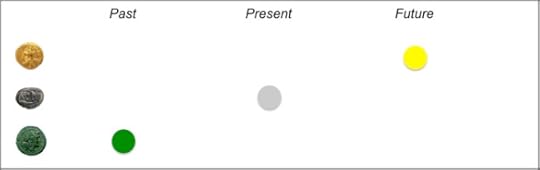

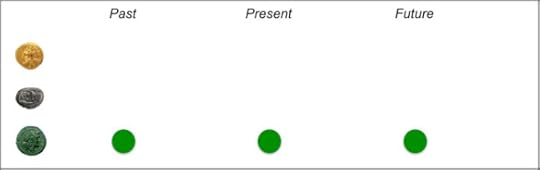

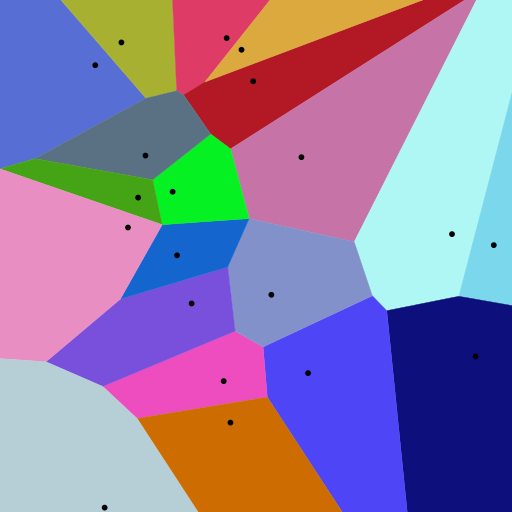

When you start looking at these views in terms of how they could be represented visually, you realise that they can be shown neatly as a timeline with three times (past, present and future) and three values (Gold, Silver and Bronze). [Note: Classically educated readers will probably spot that I’ve simplified Hesiod’s Ages of Man model, and have used Bronze where the original model used Iron, to make the underlying principle more clear.]

This gives you three possible values for the past, each of which can then go to each of three possible values for the present, and then to each of three possible values for the future. That gives you 3 x 3 x 3 possible combinations, making a total of 27.

In the next section, I’ll work through some of those 27 combinations. I’ll deal with the 28th view in the final section.

The 27 combinations

Here’s Plato’s view, shown as a diagram. I’ve used yellow circles to represent the Golden Age, grey circles to represent the Silver Age, and green circles to represent the Age of Bronze.

In Plato’s version of events, things start off well, then decline to the present day, and will keep declining in the future.

Here, in contrast, is Hegel’s view. Things start off crude and bad, but get steadily better, and will some day attain a mystical wonderful ideal.

Here’s a different view, in which everything was, is, and will be wonderful. It’s the sort of view favoured by Dr Pangloss, in Voltaire’s Candide.

Here, in contrast, is the Eeyore view, of gloom, more gloom, and yet more gloom.

Those examples all involved views of history and/or life.

However, you can also apply exactly the same approach to stories, which have an initial state, a middle, and an end state.

The image below shows a classic story structure, involving fall and rise, with an ending happier than the beginning. In terms of story grammars, it starts with an awareness of a lack, then goes through various challenges, and ends with a resolution, which fills the lack.

It’s the structure of Emma, and of every romantic tale by Dame Barbara Cartland, where the heroine starts off with a life that requires only a husband to bring complete happiness; after tribulations along the way, the story ends with marriage and bliss.

Here, in contrast, is a classic Greek tragedy structure, involving rise and precipitous fall, with a body count at the end. It’s also a view of history that has been widespread from Ancient Greece to the present day: A particular person or a nation rises for a while, but will eventually fall.

I won’t go through all the other possible combinations, because that would take too long, but the principle should be clear by now.

This approach gives a clean, simple model for categorising views of history and fiction. The same principles apply to politics, which are closely intertwined with beliefs about history and about underlying principles in human events.

The 28th view

All the models above are based on the underlying assumption that a particular point in time can be meaningfully described with a single value judgment, as either Gold or Silver or Bronze.

Reality, however, tends not to work that way. That’s the core of the 28th view, which can be summarised as the “Do you really think it’s that simple?” view.

Often, in history, one nation’s Golden Age is golden at the expense of its neighbours. There’s a wry classical-era remark about a Roman provincial governor which sums it up: “He came to our rich province a poor man, and left our poor province a rich man”. It’s the same within nations, where an age that was golden for one part of the population was often very different for other parts.

So, as is often the case with philosophers, there’s an interesting phenomenon going on, but some of their explanations for it have nudged much of history and philosophy and politics into a direction which isn’t very helpful.

Thucydides the historian was well aware of these issues before Plato became famous, and had few illusions about the realities. The philosopher Karl Popper was also very well aware of just how dodgy Plato’s arguments were, and wrote scathingly and at length on the subject. He was equally scathing about Hegel’s writings about progress.

It’s an important issue, because beliefs about society and history have a profound effect on politics, and on what happens in our world. Simplistic beliefs aren’t likely to have a good effect.

This doesn’t mean that the concept of progress, or the concept of decay, should be abandoned. When they’re applied on a smaller scale, to topics such as medical knowledge or urban sanitation systems, then those concepts are much more useful.

So, how could we tackle these concepts in a more useful way?

In technical terms, they need to be used only within their range of convenience, i.e. in contexts where they can be applied meaningfully.

Also in technical terms, they need to be properly operationalised, i.e. translated into specific terms that can be measured reasonably accurately.

They should also be used in combination with game theory and systems theory, which were created to model exactly the sorts of competition for resources that make these concepts meaningless when applied at the scale of nations or periods of history.

I’ll close with a chicken joke about Hegel. It isn’t the best joke ever, but it gives an idea of what his philosophy is like, and besides, you don’t get a chance to tell a joke involving Hegel and a chicken every day.

Q: Why did the chicken cross the road?

Hegel: To realise the reason in history.

As I said, not the best joke ever; it’s probably a good place to end…

Notes and links

Sources of original images:

“Stater Lampsacus 360-340BC obverse CdM Paris” by Unknown – Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2008-04-13. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stater_Lampsacus_360-340BC_obverse_CdM_Paris.jpg#/media/File:Stater_Lampsacus_360-340BC_obverse_CdM_Paris.jpg

“Silver croeseid protomes CdM” by Jastrow – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_croeseid_protomes_CdM.jpg#/media/File:Silver_croeseid_protomes_CdM.jpg

Cropped from: “Petelia Æ 14 mm 610084″ by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Petelia_%C3_14_mm_610084.jpg#/media/File:Petelia_%C3_14_mm_610084.jpg

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

July 2, 2015

Getting an overview of the literature via review articles

By Gordon Rugg

Review articles are an extremely useful resource when you’re starting a literature review, and when you’re about to start some new research. However, most students have never heard of them.

In today’s article, I’ll describe what they are, how to find them, and why they’re so useful.

I’ve written briefly about review articles in a previous article. Here’s what I said there.

You should also get useful information about professional consensus from review articles , whose purpose is to give an overview of key research developments in a field over recent years (usually about the last ten to twenty years). These are an invaluable resource for new researchers, since they give a synoptic overview of the field, and they’re usually written by major figures within the field. You may not agree with the opinions of the person writing the review article, but you can usually be fairly confident that they will have identified the most significant concepts, findings and publications.

So just what does that mean, when you unpack its rather terse phrasing?

Telling you what the key points are

For a start, it means that a good review article will tell you what the really important things are that you need to know about, and that you probably need to mention in your own literature review (the “key research developments” phrasing above).

Sometimes you’ll need to use your judgment, and decide that one of those topics may be important in other parts of the field, but isn’t important in the part that you’re writing about. If you do that, then the smart tactic is to mention the topic in question, with a reference to the review article, and to explain briefly why you’re not going to explore it in detail. That way, you reassure your readers that yes, you know about the topic, and yes, you’ve made a deliberate decision not to go into detail about it.

This is a particularly useful tactic if you’re writing your PhD thesis, since it shows the examiners that you know about the topics that you ought to know about. If you simply omitted any mention of the topic in question, then the examiners would assume that you did so because you’d never heard of it, which is not a signal that you want to send out.

Telling you what the key publications are and who the key players are

Knowing about the key topics is important. However, it’s also important to know what the key publications are which describe and discuss those topics. Review articles not only tell you what the key topics are; they also tell you what the key publications are that relate to those topics, so you can add those publications to your to-read list, with an inward sigh of relief that you won’t have to track them down for yourself.

That’s an obvious advantage of review articles. A less obvious advantage is that they also tell you who the key players are in a given field. This is very useful for various reasons. One is for planning your networking and career plans. Once you know who the main players are in your area, you can start doing your homework about them, and deciding which of them you would really like to work with. You can then start building up your profile in a way that improves your chances of getting to work with them.

Another reason that this knowledge is useful is that it helps you in your searches for more recent relevant publications that date from after the publication of the review article. If you know that Smith & Green are key players in your field, then you can search for their names in the relevant bibliographic database, or look at the “publications” part of their home pages on the Web, and see what they’ve published recently, so you’re up to date.

Giving you a coherent overview

One of the problems with wading through the literature article by article is that you often have trouble working out what the big picture is. Often, it’s because there are two or more rival approaches making contradictory claims. Sometimes, it’s because researchers are using two or more very similar-looking terms in a way that causes confusion (for instance, the two very different interpretations of the acronym NLP).

A significant advantage of review articles is that they provide you with a clear, coherent overview. Also, the overview is likely to give a reasonably fair and balanced overview, since otherwise it wouldn’t have got past the reviewers and into print.

You don’t have to agree with that overview, but the key point is that the overview will probably be reasonably coherent and clear, which is a good start.

Telling you about gaps, problems and opportunities

Review articles don’t just tell you what’s been written about a particular topic. They also usually tell you explicitly about what hasn’t been written.

For aspiring researchers, this feature of review articles is a gold mine. You can read through review articles, spotting for gaps that they’ve identified, and that someone such as yourself could usefully investigate, with a good chance of publication at the end of the research (since your research would be plugging an established gap in the literature).

This leads on to another good feature of review articles.

Giving you someone else to blame

Suppose that you have a wild hunch which came to you in a dream; suppose further that you spend a couple of years doing some expensive research to find out whether the hunch is right. Suppose that you discover that the hunch was totally wrong.

What can you salvage from that wreckage? Probably, nothing. Usually if your hunch is wrong, you’re sunk, because the absence of what the hunch predicted is not a significant absence.

It’s a very different story if you test out one of the claims made in a review article, and discover that the claim was wrong. In that case, the absence of a result will almost certainly be a significant absence, so you can write about the significant implications of this outcome, secure in the knowledge that you can blame the mistaken claim on the writer of the review article.

(Note for readers who aren’t strong on irony: Yes, I was partly joking there, and no, you don’t phrase it that way in the write-up; what you do is to explain the reasons for expecting the result predicted in the review article, with due reference to the literature, so that you’re explaining the significance of the absence with regard to previous research findings, not saying that the eminent writer of the article was wrong, which would be tacky, and also very unwise…)

How to find them

One easy way of finding review articles is to go onto the appropriate bibliographic database, or Google Scholar if appropriate, and type in the search string “review article” in inverted commas, followed by the term that you’re interested in.

The image below shows a Google Scholar search for review articles about stakeholder analysis. I’ve put “stakeholder analysis” in inverted commas so that the search doesn’t produce millions of false positives from records that include mention of analysis but not of stakeholders.

Here’s a close-up from the search above, showing the type of result that you can get with this sort of search.

This particular example illustrates another neat feature of review articles. Usually, they include references to previous review articles, so once you’ve found one, you can use it to find a chain of others, which will in turn lead you to others, giving you a good guide to key reading for the last few decades. If you really get the hang of this, then a few hours of focused work can identify a batch of review articles that contain all the key concepts and references that you need for a substantial piece of research. (You’ll still need to find and read those other key articles that appear in the references of the review articles, but at least this way you’ll be focusing your reading on relevant articles, not wasting a lot of time reading things that turn out to be irrelevant).

The broader context

A closing thought for new researchers: Review articles aren’t “objective” or “unbiased”. Nothing is. Nothing can be. If you use those terms in something that you write, experienced researchers will probably view it as a sign of naivety. Good research takes account of this, and factors out a specified subset of potential problems via good research design.

Here’s a brief example. Suppose you’re interested in gender stereotypes about risk. That topic is itself located within a framework of assumptions and world views, about what is worth researching and what isn’t, and about which values we can take for granted versus which beliefs are socially unacceptable. In that sense, it can’t be objective or unbiased.

I’ve written about this, with particular reference to the concept of “objective facts” in a previous article; I’ll doubtless return to it in future articles.

For the moment, though, I’ll focus on how research design interacts with social framing of research questions.

There are a lot of obvious sources of potential distortion in the data that you might collect when investigating this topic. For instance, you’d probably get differences depending on whether the data collection was carried out by males or females, etc.

However, you can neatly sidestep a lot of those issues by using the approach that one of my former students did for her undergraduate project. She gave participants a single sheet of paper which outlined a one-paragraph scenario. In the scenario, Chris had the choice between a safe investment which would probably produce a modest return, and a risky investment which might produce a high return, but which might be a complete loss.

The neat part was the closing sentence. For half the participants, the closing sentence was: “What advice would you give him?” For the other half, the closing sentence was: “What advice would you give her?”

Everything else was identical for all the participants; only the perceived gender of Chris in the scenario was different, so any differences in results could only come from random chance or from the two wordings. Statistics allow you to work out how likely the “random chance” explanation is, giving you a nice, clean answer. And yes, in case you’re wondering, the advice that people gave male Chris was to go for the high risk investment, and the advice that people gave female Chris was to go for the nice, safe option.

So, that’s how you can use review articles to get a swift, high-level overview of a field, including significant gaps and problems in that field which you can treat as opportunities. That’s also how you can reconcile human agendas in those reviews with research findings that are robust and more than just a matter of opinion.

On which note, I’ll end. The next article in this mini-series will be about how to know when you can scale down your literature review.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/07/25/literature-reviews/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/06/25/the-quick-and-dirty-approach-to-meta-analysis/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/10/16/finding-the-right-references-part-1/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/21/academic-writing-and-fairy-tales/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 25, 2015

Critically reviewing the literature, the quick and dirty way

By Gordon Rugg

I’ve blogged previously about literature reviews, and about the significant difference between a literature review and a literature report. There are links to relevant previous posts at the end of this article.

Literature reviews are an important part of research. They’re how you find out what’s been tried before, and what happened when those previous approaches were tried. They’re a good way of identifying potential problems that you might encounter in your own research, and a good way of identifying gaps in previous research, which might be your chance to achieve fame and fortune by filling one of those gaps with a brilliant new solution.

This article is about one key aspect of literature reviews, which is that literature reviews involve critical analysis of the key issues. That raises the question of just how you set about starting a critical analysis.

In case you’re wondering whether this really is a big deal, then there’s one very practical consideration that can make a difference to the outcome of your time at university. One of the criteria for getting distinction-level marks on most taught university courses is showing that you’ve done critical independent reading. This is also a major criterion for getting through a PhD viva, so all in all, it’s a big deal.

But just what is a critical review of the literature anyway, as opposed to a non-critical one, and how can you possibly do a critical review of a literature that may include tens of thousands of journal articles and thousands of books? It’s not physically possible to read all of that literature in the three years of a typical undergraduate degree or PhD, let alone a one-year MSc or MA.

This blog article is about one quick and dirty way of making a good start on a critical literature review.

If you’re doing the literature review properly, you’ll be searching the relevant specialist bibliographic databases for your field.

If you’re a fairly typical student, feeling lost and bewildered by discovering this new world of advanced assessment of a huge literature, then it’s quite possible that you’ve never heard of specialist bibliographic databases. I’ll leave those to the side for the time being, and instead use Google Scholar as a familiar, friendly place to start.

Let’s suppose that you’re doing a literature review about software build projects. You know about the waterfall model, where the project team gather the requirements at the start, then plan the project, and then build the software and show the completed product to the client for sign-off. You’ve never heard about any other models, and you don’t know the strengths and weaknesses of the waterfall model.

So, how do you start?

The method I’m describing today involves going onto Google Scholar, and typing in the word critique followed by the phrase “waterfall model” in inverted commas. The inverted commas are important, because otherwise you’ll get a lot of false positives (i.e. records that aren’t relevant, which were found because they include the word “model” somewhere or the word “waterfall” somewhere but which aren’t about the waterfall model).

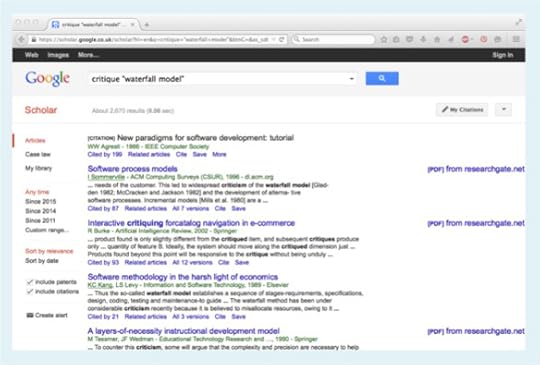

What you get from that search will look something like this.

A search for critique “waterfall model”

Here’s a close-up of the relevant part.

This is the first page of results from your search, and already you’ve found articles that describe problems with the waterfall model. If you’re going to do a software build, then you need to know what those problems were, and what the alternative approaches might be. The Sommerville article and the Kang & Levy article both describe widespread criticisms of the waterfall model, and the Somerville article explicitly mentions other, different, software development methods that were likely to avoid those problems.

That’s a pretty good start. You already have two articles that you can read and cite in your literature review, which are both critical of the waterfall model. These articles showing the person reading your literature review that you’re going out and finding relevant critical literature on your own.

If you’re of a cynical nature, you might have noticed that both those articles are from the 1980s, and you might be wondering if that’s a problem.

If you’re of a cynical nature, you might be pleased to learn that it isn’t necessarily a problem. If you’re cynical and lazy, you can simply write in your literature review something along the lines of: “The limitations of the waterfall model were identified as early as the 1980s” and then move swiftly on. If you’re more conscientious (and also more careful about whether those old problems might have been fixed by now) then you’ll be well advised to look for some more modern articles, to see what the situation is now.

What you often find is that there’s a lot of literature about a problem when it’s first identified, and that the literature about it diminishes as consensus is reached in the field. After that point, the topic will usually just be mentioned in passing as a throwaway sentence in the introductions of articles, or it might not be mentioned at all. (For instance, you won’t see many recent physics articles that say much about the problems with the concept of phlogiston, or many recent medical articles that say much about the problems with the “four humours” model of medicine.)

Where do you go next? One sensible next step is to start a list of the other methods that are being mentioned, and to repeat the same type of search, only with the word critique combined with the name of each other method. That will give you a quick and dirty overview of the main issues relating to software build methods. There’s still a lot more work to do before your literature review is finished, but this approach will give you a fast overview of the key points, so that you’re not drowning in a huge sea of detail.

Once you have that overview of the key points, you should know the main arguments in the field being covered, which makes it much easier for you to start critically reviewing the strengths and weaknesses of those arguments in your literature review.

One quick practical point before I close. You might be wondering why I’ve recommended the word critique rather than more familiar plain English terms like criticism. There’s a reason for this.

The word critique tends to be used mainly in the context of high-level academic criticisms, whereas the word criticism is used in a broader range of contexts. This means that a search using critique will usually return a higher proportion of relevant records. However, this doesn’t mean that you should ignore the word criticism. A search using criticism will return a slightly different set of records, some of which will be relevant records that you wouldn’t have found using critique. It’s therefore usually a good idea to do several versions of your search, using words such as critique, criticism and critiques and criticisms in the plural. These may or may not return different results from each other, depending on which search engine you’re using, and which bibliographic database you’re searching. (I never said that doing the whole of the literature review would be easy; I only said that this was a good way of making a quick and dirty start…)

So, that’s one way of approaching a critical literature review. I’ll blog about others in later articles.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/07/25/literature-reviews/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/06/25/the-quick-and-dirty-approach-to-meta-analysis/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/10/16/finding-the-right-references-part-1/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/21/academic-writing-and-fairy-tales/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 18, 2015

Bad questionnaires, gender and ethnicity: When researchers achieve profundity by mistake

By Gordon Rugg

My usual response to badly assembled questionnaires involves a rant, followed by a dissection of the methodological issues involved and of various relevant bodies of theory.

Sometimes, though, a questionnaire manages to achieve a level of badness so extreme that it transcends its own awfulness.

Today’s example is one of those. It’s a question from an unidentified questionnaire. It’s asking about sexuality. It offers one option which you don’t usually see in this context. Admittedly, it’s probably the result of a copy and paste error, but that’s a minor detail. (Yes, I’m being ironic there…)

Anyway, here it is, in all its blighted majesty…

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/426716133415869162/

Beneath the humour, there are actually some deep and interesting questions about how and why humans categorise themselves and each other. Some of those questions have been in the public eye recently because of the case of Rachel Dolezal. Just how do we decide about ethnicity and gender and a pile of other categories that can have major effects on people’s lives?

I’ll blog about this topic in later articles. For now, though, I’ll quietly enjoy the experience of a bad questionnaire providing some fairly harmless entertainment, and raising some (probably unintended) thought-provoking questions.

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

I’ve blogged about categorisation and gender here:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/10/24/gordons-art-exhibition-part-2/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 11, 2015

Significant absences

By Gordon Rugg

In a previous article, I looked at the concept of infinity, symbolised by the circular Buddhist enso symbols in the banner below.

In today’s article, I’ll look at the concept of absence, symbolised by the Victorian racehorse in the banner below.

It’s an interesting concept, and a very useful part of the researcher’s toolkit, either as an elegant method of first choice for demonstrating sophisticated methodological mastery, or as a desperate last resort that might just manage to drag victory from out of the jaws of looming defeat.

Infinity and absence: A tale of ensos, zeroes, racehorses and unsleeping dogs…

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article

There are plenty of excellent books and articles about the concept of zero, and its enormous significance for mathematics, so I won’t go into that topic.

Absence has had less attention. It’s different from zero, although there are quite a few areas of overlap.

I’ll use two examples to demonstrate some advantages of using the concept of absence systematically.

The first, broader, example is the concept of significant absence.

This concept is well established in some disciplines; it’s a familiar friend in archaeology, for instance.

The most famous example is the Sherlock Holmes story Silver Blaze, which is the one with the dog that didn’t bark in the night. Holmes correctly spots that the absence of the reaction from the dog is significant, and is an indicator that the crime was an inside job.

Some absences are not significant; for instance, if the dog in the story had been a quiet, friendly animal that didn’t often bark, then the absence of a bark in the night wouldn’t have told Holmes anything about who the criminal might be. Since, however, the dog was a distrustful watchdog, the absence of a bark in the night told Holmes that the criminal was someone that the dog knew well, which was why the dog didn’t bark.

In archaeology, the absence of finds is often important; it tells us about what was going on at a particular place. Some of the biggest prehistoric sites, for instance, such as Stonehenge and Pueblo Bonito, have a significant absence of ordinary domestic finds around them. The absence tells us that the sites didn’t have people living in or near them. Instead, the sites were special places that people travelled to from a distance, and where people might stay for a short time, presumably for religious and/or ceremonial reasons.

In research design, you can get some very interesting insights from what is significantly absent in your results. You might, for instance, have every reason to expect that you will find a particular result, based on the previous literature, but then you find that the result is significantly absent from your data. That can be a very good thing indeed, for an academic researcher. Sometimes this happens through design, where the researcher has a shrewd idea of what to expect; sometimes it happens by accident.

The classic example was the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887. In brief, the researchers set out to measure the speed at which the earth moved through luminiferous ether. They found a significant absence of any evidence of movement (or of luminiferous ether). This was a complete surprise, and sparked a massive flowering of new ideas in physics, the most prominent of which was Einstein’s theory of relativity.

On a less noble note, if you’re into dirty academic in-fighting, a classic way of undermining an approach that you despise is to demonstrate that there’s a significant absence of improvement from using that approach.

For instance, cynics and unkind people quite often claim that there is a significant absence of measurable benefit from going through a teacher training course, or going to business school, in terms of professional performance afterwards.

On the social and political front, there are numerous significant absences in the media, in literature, in history books, and in most forms of high culture. Minority groups, for instance, are usually significantly absent in most of these places.

The same principle extends to research, where there are numerous significant absences in what is researched, often because of social taboos. For instance, sex is a significant feature of human life, but there’s a significant absence of departments of sexual studies in the vast majority of universities.

This absence has not gone un-noticed, and is one of the better points made by postmodernists and by sociologists of science.

The second, more specific, example I’ll use is the concept of silence ownership.

This concept comes from the field of discourse analysis. As the name implies, this field involves analysing discourse, including conversations between people.

One of the things that you find when you analyse conversations systematically is that people have the concept of taking turns in a conversation. This in itself is no great surprise. However, the turn-taking includes some less obvious conventions about what happens during a silence. Some silences are treated as pauses, where the person who has been speaking is temporarily silent; other silences are treated as endings, when the speaker has finished speaking. If you start talking during a pause, that’s generally perceived as rude, whereas if you start talking after an ending, that’s acceptable. So, the silence during a pause belongs to the person who has been speaking.

It’s a neat example of how there can be different types of silence, and different types of absence. Like the concept of zero, the concept of absence is powerful, in ways that aren’t immediately obvious, but that make a huge difference to the world.

On which edifying note, I’ll end, and wonder whether I should have included the quote from A Man for All Seasons about types of silence, or whether its absence is not significant.

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of banner images:

“Enso” by Kendrick Shaw – Own work. Licensed under CC0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enso.svg#/media/File:Enso.svg

“The Adventure of Silver Blaze 09″ by Sidney Paget (1860-1908) – http://www.sshf.com/encyclopedia/index.php/The_Adventure_of_Silver_Blaze. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Adventure_of_Silver_Blaze_09.jpg#/media/File:The_Adventure_of_Silver_Blaze_09.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/66/ENSOLOGO2013.jpeg

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 5, 2015

Strange places

By Gordon Rugg

There’s a scene in the movie Byzantium where a vampire hesitates at a threshold, waiting for her intended victim to invite her inside. The setting is a run-down seaside town, out of season. It’s a scene that combines several types of unsettling strangeness, which makes it a good starting point for today’s article about strange places.

Two boundary spaces: Image credits are at the end of this article.

Two boundary spaces: Image credits are at the end of this article.

Thresholds

If you’ve ever wondered just why vampires have such a problem with thresholds, then you may be reassured to know that you’re not alone. There’s been a lot of work by social anthropologists and folklore researchers on this and related questions.

What they’ve found is, among other things, that vampires don’t just have a problem with thresholds. Vampires also have problems with crossroads in many stories. Crossroads, in turn, are not just an issue for vampires. In a lot of stories, crossroads are a place for meeting the devil, and in a lot of cultures, they’re a place for executing criminals and for burying social outcasts.

The common theme that emerges from research in this area is that most societies have a problem with places which involve significant transitions. A lot of those places are viewed as sacred, such as temples. Usually those spaces are kept separate from the ordinary world by physical boundaries, such as ditches and walls. The banner image shows the boundary ditch for Avebury, an enormous henge monument that makes Stonhenge look like small stuff. That boundary ditch was originally over eleven metres deep and over twenty metres wide. A ditch that size is making a significant statement about just how important the boundary is between the outside world and the space enclosed within the ditch.

Usually, people have a problem with the place where you move between the ordinary world and the non-ordinary one. That boundary place is neither one thing nor the other, and people tend to find this uncomfortable. One common result is the use of a special transition space. In many British churches, this takes the form of the lych gate, such as the example below.

“St Michael’s Manafon lych gate” by John Firth. Full link and details at the end of this article.

Transitional places such as these are known in social anthropology and related fields as liminal zones, from the Latin limen, meaning “threshold”. Most societies have strong conventions about how you behave when you enter a liminal zone; a common example both for sacred places and for ordinary homes is taking off your shoes in the liminal zone.

The concept of liminal zones can also be applied to time, usually in the form of life events, such as the transition between childhood and adulthood. The Wikipedia article on liminal zones gives a good initial overview of this concept. I’m not going into the time issue in this article, for reasons of brevity, but it’s a fascinating topic.

Returning to physical liminal zones: These take various forms. Usually, they’re the boundary between two types of space, but sometimes an entire space may be liminal. Hotels are a classic example. They’re neither completely a public building, because you use them for private activities such as sleeping, not completely a private building, because they’re available for anyone to stay in.

The setting of a hotel in an out-of-season seaside resort has been used repeatedly in horror stories, including at least one classic. Seaside resorts are themselves liminal spaces, at the boundary between land and sea; out of season, they’re neither places of entertainment nor normal towns. There’s a subculture of people who enjoy that experience; there’s something deeply unsettling and evocative about knowing that nobody else is staying in the huge, run-down old hotel where you are spending the night, especially when you hear creaking noises in the corridors in the small hours of the morning…

Moving rapidly on from that disquieting thought: Seaside towns are also boundary places in other ways. This takes us into the world of social geography and economics.

Social geography, economics and liminal zones

One of the neat concepts of social geography is Thiessen polygons. They’re a subset of what is known mathematically as Voronoi diagrams. The core idea is that if you plot the mid way spaces between towns, then you can see regular polygons around each town. This effect appears particularly clearly in homogeneous landscapes, such as the Dutch countryside, where there aren’t distortions in the polygon distributions due to mountains, moorland, etc.

Here’s a hypothetical example, from Wikipedia.

“Euclidean Voronoi diagram” by Balu Ertl – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euclidean_Voronoi_diagram.svg#/media/File:Euclidean_Voronoi_diagram.svg

In this diagram, each black dot can represent a town, with the coloured area around each dot representing what’s known as the hinterland of the town. The hinterland provides most of the resources used by the town, such as food, people to staff the town’s essential services, etc. Often, the size of the hinterland corresponds to critical distances in antiquity, such as the maximum feasible distance for traveling to a market and returning the same day without having to stay overnight in the town.

Seaside towns have only half as much terrestrial hinterland as inland towns. This isn’t a huge problem when a seaside town is successful; in those times, the sea provides access to a “virtual hinterland” in the form of trade from other ports and of harvests from fishing, etc. However, this becomes a significant problem when a seaside town isn’t successful.

The problem is compounded because seaside towns will often get less passing traffic than inland towns; there may be coastal traffic, but that seldom compares in volume with the traffic that passes through an inland hub.

So, there are practical reasons for some liminal zones being different. However, that doesn’t explain why liminal zones are such a big issue in religion and mythology.

I think that the explanation for religious and mythological liminal zones being so important involves a couple of usual suspects, namely human categorisation, and human problems with Necker shifts.

Necker shifts, categorisation and the uncanny valley

In a previous article, I discussed the problems that arise when you encounter an ambiguous situation, where one possible explanation is harmless, but the other possible explanation is threatening.

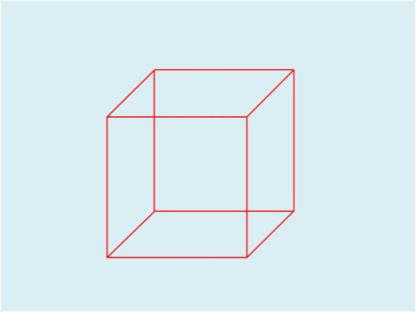

I linked the underlying cognitive mechanism back to the concept of the Necker cube, a visual illusion where a wireframe drawing can be perceived in two mutually exclusive ways. Here’s the wireframe drawing.

Here are the two ways in which the drawing can be perceived, either with the front of the cube at the bottom left, or with the front of the cube at the top right.

I think that this is probably what’s going on with liminal spaces. You don’t know which category a liminal space falls into; whether it’s part of the safe, ordinary world, or part of the scary non-ordinary world.

I think that a similar effect underlies the phenomenon of the uncanny valley, a phenomenon named by the Japanese robotics researcher Masahiro Mori. He found that the more human-like a robot is, the more people like it, up to a point where suddenly people aren’t immediately sure whether they’re dealing with a machine or a human. Most people find that ambiguity deeply unsettling. This concept has been picked up by researchers interested in human perceptions of human-ness. For instance, corpses and most of the monsters in horror movies are in the uncanny valley between definitely human and definitely not human.

Here’s the classic picture of an uncanny valley robot.

Repliee Q2 (detail); full link and credits at the end of this article

This concept has attracted a lot of attention, both in academic research and in popular culture; it’s generated some very thought-provoking ideas.

Closing thoughts

So, in conclusion, liminal spaces are probably one example of a much wider phenomenon, namely that most human beings dislike ambiguity, particularly when one of the possible interpretations is threatening.

The movie scene that I started with, from Byzantium, piles one threatening ambiguity on another. The vampire waiting at the threshold is neither truly human nor truly non-human; the threshold is neither completely inside the house (which should be a place of safety) nor completely outside it; the seaside town is neither completely of the land nor of the sea; the town is a resort, out of season, so neither properly a place of entertainment nor properly a normal town.

That’s the dark side of ambiguity; is there a light side? The answer is that yes, there can be a light side, as described below.

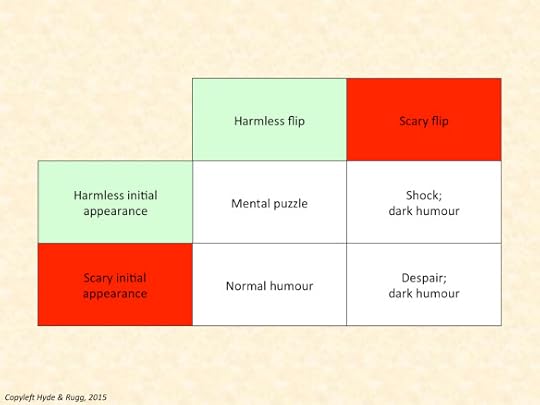

You can show the possible resolutions of ambiguity as a matrix, like this.

Most people enjoy ambiguity when the possible interpretations are non-threatening; examples include mental puzzles, abstract art and “visual jokes” such as images that can be parsed in two different ways. I’ve blogged about this here. Mental puzzles such as crosswords and riddles probably also fit into this category.

Almost everyone enjoys ambiguity where the initial appearance is threatening, but the actual resolution is very different, and non-threatening; this is the basis of humour, which I’ve blogged about here.

What about situations where the actual resolution involves bad news for someone or something? The short answer is that I’m not sure. There’s been a lot of good work on the physiological mechanisms of response to threatening situations, but that’s different from what I’m talking about here. There’s also a lot of interesting work on the tropes in horror movies and related media, but again, that’s a different issue. There may well be a literature on this aspect of the cognitive mechanisms that I’m looking at in this article, but I haven’t bumped into it yet. What follows next is therefore speculative.

If the switch is from harmless appearance to sudden realisation that the situation is actually scary, the usual reaction is visceral shock. Some people find that situation genuinely funny, particularly if they’re observing it happening to someone else, but that perception is generally viewed as sadistic “sick humour” in current society.

If the switch is from initial apparent scariness to a realisation that the situation is actually scary in a different way, then a common response is despairing horror; this is a classic plot device in horror movies, either as a bleak ending, or as the low point from which the protagonist fights back. Again, some people might find this genuinely funny, but this perception is not the norm.

So where does dark humour fit in?

I think that a key feature of dark humour is that it arises from empathy for the individual in the scary situation, whereas sick humour does not show any empathy for that individual. Dark humour is common among people who have chosen to work in a role that involves helping people in scary situations, often at personal risk. But if they care, why do they make jokes about it?

I think that dark humour takes us back to the same mechanism that drives some people’s attraction to scary things and scary places. I suspect that what’s going on is a desire to master the scariness. Ghost stories and horror movies provide a mechanism for mastering the scariness via fiction, through becoming familiar with the object of fear and learning about its limitations and about ways of handling it. Dark humour probably falls into the same category. It gives you a coping strategy that lets you see the situation in a different way.

There are also ways of mastering the scariness via physical actions. Extreme sports confront the object of fear within set boundaries – for instance, climbing or bungee jumping. “Prepping” is another form, that involves making physical and organisational preparations for societal breakdown.

Rituals are another classic mechanism for dealing with frightening unknowns, taking us back to the starting point of this article. In the past, rituals often involved negotiation with the scary entity. Iron Age Celtic societies, for instance, offered gifts to the deities of the underworld. Some of the most spectacular remaining pieces of Celtic art were such gifts, offered in places where the Celts believed that our world joined the underworld – frightening, liminal places, such as swamps, that were neither land nor water. Here are some examples.

Links and credits at the end of this article

A lot of other interesting things happened in Iron Age bogs, but that’s a topic for another article, some other time…

So, in summary: I think that liminal places are perceived as scary because of human problems with categorisation.

On which prosaic note, I’ll end.

Notes, links and sources of images

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of banner images:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_ditch_at_Avebury_henge_-_geograph.org.uk_-_401970.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arnold_Boecklin_-_Island_of_the_Dead,_Third_Version.JPG

Sources of other images:

“St Michael’s Manafon lych gate” by John Firth. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Michael%27s_Manafon_lych_gate.jpg#/media/File:St_Michael%27s_Manafon_lych_gate.jpg

“Repliee Q2″ by BradBeattie at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Repliee_Q2.jpg#/media/File:Repliee_Q2.jpg

Sources of composite image of votive offerings: