Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 25

August 20, 2013

Why birds can fly: Brought to you by classical logic

By Gordon Rugg

You might already be familiar with the Monty Python scene where one of King Arthur’s knights uses logical reasoning to show why witches and ducks float. As with much of Monty Python, it’s fairly close to something that actually happened.

Here’s Vitruvius, the famous Roman engineer and architect, using the four elements theory (that all things are made of various mixtures of air, fire, water and earth) to explain why birds are able to fly.

Winged creatures have less of the earthy, less moisture, heat in moderation, air in large amount. Being made up, therefore, of the lighter elements, they can more readily soar away into the air.

(From his Ten Books on Architecture)

Disclaimer: If you try using this quote as justification for throwing an alleged witch into a pond, then you’re on your own – this post is tagged under “error”…

August 17, 2013

Is that handaxe Windows-compatible? The concept of “range of convenience”

By Gordon Rugg

A “Useful concept for the day” article

This is a replica handaxe that I made in my archaeology days. It’s turned out to be invaluable as a demonstration of assorted useful concepts, though I didn’t expect that when I made it.

What would your response be if someone asked you whether that handaxe is Windows-compatible? You’d probably be surprised by the question, because it’s meaningless. As for explaining why it’s meaningless, though, that’s not so immediately obvious.

This is where range of convenience comes in. It’s from George Kelley’s approach to psychology, namely Personal Construct Theory (PCT). It dates from the 1950s, but still has a strong following today because it offers a clean, systematic, rigorous way of modeling how people think. PCT has a rich, well-developed set of concepts for handling language and categorisation and ideas. Range of convenience is one of those concepts.

In brief, PCT argues that any word can only be meaningfully applied within a particular range of contexts, i.e. the range of convenience. Sometimes that range is narrow; for instance, the concept of Windows-compatible can only be used meaningfully when applied to computer equipment. Sometimes the range is broad; for instance, the adjective good can be applied to a huge range of things.

Some concepts have sharply-defined ranges of convenience, such as Windows-compatible. In general, either an item can definitely be categorised in terms of Windows compatibility, or it definitely can’t.

Other concepts, though, have a much more fuzzy boundary to their range of convenience, and that’s where problems can arise.

Some examples of disagreement about range of convenience that often lead to strong feelings of bafflement and/or rage:

The concept of wave and particle, if applied to electrons in physics

The concept of customer as opposed to patient or student in public policy

The responses that you have to choose between in almost any amateur questionnaire

Range of convenience is a useful concept, and it helps make sense of a lot of things that you know to be wrong, but without being able to put your finger on quite why you’re sure they’re wrong. Other useful concepts will follow in later posts.

Notes

Bannister & Fransella’s book Inquiring Man is a good introduction to Personal Construct theory; it’s very readable, short and clear:

http://www.amazon.com/Inquiring-Man-Theory-Personal-Constructs/dp/0415034604

Kelley’s book about Personal Construct Theory is clear and fascinating, but a book that you can’t easily read at one sitting, because there’s so much in it that you need to think through:

http://www.amazon.com/Theory-Personality-Psychology-Personal-Constructs/dp/0393001520

As a counterpoint, for anyone who is particularly interested in this topic, Osgood et al’s book on Semantic Differential includes an article famously asking whether a boulder is sweet or sour, and claiming to have found the answer, by extending concepts far, far outside their range of convenience:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Measurement-Meaning-Charles-Osgood/dp/0252745396

August 16, 2013

A very British mystery, part 5: Gavin Finds a Typo

By Gordon Rugg and Gavin Taylor

The story so far: This is a series of articles about the D’Agapeyeff Cipher, a short ciphertext that’s never been cracked. It first appeared in Alexander D’Agapeyeff’s 1939 book Codes and Ciphers. It’s a good testbed for codebreakers who have to deal with short texts. In the previous episodes, we’ve listed the codes described in the book, plus the worked examples that D’Agapeyeff used. In today’s gripping episode, we focus on a typo that Gavin found in Codes and Ciphers. It’s more exciting than it sounds, though admittedly that isn’t the most difficult challenge in the world…

Opening question: Does anyone apart from sad pedants really care about typos, and if they do, is that just a sign that they really ought to get a life?

In fact, a lot of people care a great deal about typos, in a lot of different fields, and for a lot of very good reasons, most of them involving money and the law. They’re also a serious issue if you’re applying for a job. A high proportion of organisations will reject a job application because of a single typo in the covering letter.

So why do people care so much about typos, and what does Gavin’s discovery mean for anyone interested in the D’Agapeyeff Cipher?

We’ll start with job applications and recruitment.

Here’s a quote from a career site, talking about job applications and covering letters:

A top complaint with every manager and HR person in our survey noted: “I stop reading when I find spelling mistakes.”

http://www.jobdig.com/articles/655/Resume_Mistakes_Can_Cost_You_The_Job.html

That’s a common finding in surveys in this area. Organisations take spelling mistakes and typos very seriously. There are two main reasons for this.

One practical reason involves logistics. Imagine that you’re a manager dealing with applicants for a job in your organisation. Processing job applications takes time, and you may be dealing with several hundred applications for a single job. So you want a fast, simple way of weeding out the non-starters, and typos in the application are one of those fast, simple ways. They have the added advantages of being objective (so you can’t be legally accused of subjective choices that can easily shade into prejudice) and of having a practical job-related justification. That’s where the second reason comes in, as the justification for using typos as a criterion for rejection.

Companies don’t like needlessly losing money, and typos can be a surprisingly effective way of losing money. Here’s a recent example.

A hotel offered a room in Venice for one euro cent instead of 150 euros. It was a misprint, but the company had to honour its offer. The cost to the company was estimated at 90,000 euros.

You might think that this was a one-off by some employee in a local hotel, but this sort of thing happens to major international organisations too. Here’s another example – pocket computers mistakenly on sale on Amazon for £7 each, instead of £192.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/2864461.stm

Neither of those broke the bank, though they weren’t exactly cheap, and the companies involved wouldn’t love the employee who made the mistake.

Here’s a more impressive example, where the error cost the company about $220 million:

The Japanese government has ordered an inquiry after stock market trading in a newly-listed company was thrown into chaos by a broker’s typing error.

Shares in J-Com fell to below their issue price after the broker at Mizuho Securities tried to sell 610,000 shares at 1 yen (0.47 pence; 0.8 cents) each.

They had meant to sell one share for 610,000 yen (£2,893; $5,065). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4512962.stm

So, there are very good reasons why organisations are wary about taking on employees who might be responsible for mistakes involving small but important typos. You might be wondering about the laws relating to discrimination with regard to conditions such as dyslexia; that’s a good point, which goes outside the scope of this article. Dyslexia is a complex issue, which Gordon discusses in some depth in his book Blind Spot. We’ll leave this topic for now, and return to the D’Agapeyeff Cipher.

The conclusions from the previous examples are that some typos are minor mistakes that don’t really change anything, but that other typos are significant. If you’re working with codes, then typos can be a very big issue. Some codes are fairly tolerant of errors, but with others, a single mistake in the process can mess up everything which follows, leaving the rest of the message unreadable.

There have been suspicions over the years that this might have happened with the D’Agapeyeff Cipher. D’Agapeyeff was an amateur cryptographer, not a professional. It’s plausible that he might have made a simple error part-way through the encoding of his cipher, and inadvertently turned it into gibberish.

In principle, this shouldn’t have happened in a professionally produced book, with copy editors and proof readers involved. (This is another reason that most organisations are twitchy about spelling mistakes and typos in applications; if you’re putting out corporate written material, then professional copy editors and proof readers will be involved, costing time and money; they don’t love people who send them copy with a lot of mistakes in it, since the expense of correcting those mistakes will cut into the profit margin.)

In the case of Blind Spot, for instance, the copy editor and proof reader checked everything, including the gibberish text that Gordon had produced to demonstrate a point about the Voynich Manuscript.

In practice, though, there’s one significant point about the D’Agapeyeff Cipher which makes it different from the text in the rest of the book where it’s printed. The Cipher was a set of numbers, and the job of copy editor and proof reader would be to check that the numbers printed in the book were exactly the numbers that D’Agapeyeff said they ought to be. Whether or not there was an error in the cipher behind those numbers was D’Agapeyeff’s problem.

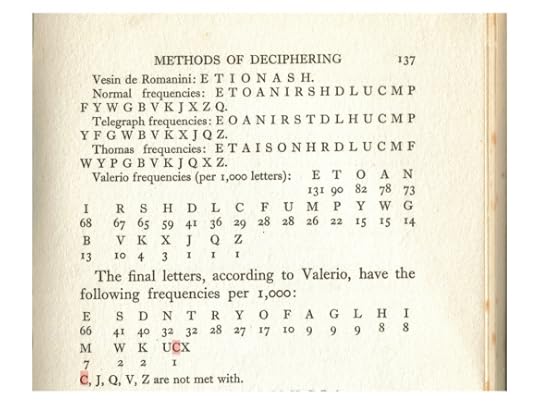

That’s where the typo that Gavin discovered comes into the story. It’s not a simple typesetter’s error or spelling mistake. It’s one that goes deeper than that. Here’s the relevant section of text.

It’s not the most immediately obvious of mistakes. However, it’s the sort of mistake that could mess up an encipherment.

In the image below, we’ve shown the error in red highlight.

The list of letters according to Valerio includes the final set of letters “UCX”. However, in the next line, D’Agapeyeff states that several letters are not met with in Valerio’s list, and includes “C” as one of the letters not in the list.

That’s inconsistent, and it’s the sort of inconsistency that could seriously mess up an encipherment if D’Agapeyeff made a similar mistake in the detail of his encoding.

So, in conclusion, this adds some weight to the suggestion that D’Agapeyeff may have made a mistake in encoding the D’Agapeyeff Cipher, and that the text in the Cipher may be hopelessly corrupt.

In the next episode we’ll discuss this possibility in more depth, and consider some suggestions about what the text of the Cipher might be.

Notes

Gordon’s book Blind Spot:

http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Spot-Solution-Right-Front/dp/0062097903

Previous episodes:

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/08/12/a-very-british-mystery-part-4-quiet-bodies/

August 12, 2013

A very British mystery, part 4: Quiet bodies

By Gordon Rugg and Gavin Taylor

The story so far: We’re working on the D’Agapeyeff Cipher, a short ciphertext that’s never been cracked. It’s a good testbed for codebreaking methods. In this series of articles, we’re collecting together resources about the Cipher for other researchers. In the previous episode, we looked at the methods that D’Agapeyeff described in the first edition of his book Codes and Ciphers, where the D’Agapyeff Cipher appeared. In this episode, we look at the solutions to the worked examples in the same book, to see what insights they might give.

When you’re trying to crack a code, you look for any clues that might possibly give you some insight into the content of the ciphertext. If you know what the text is about, then you can work backwards from that, and improve your chances of finding a solution. That’s why, for a while in World War II, one of the safest postings for a soldier on either side was in an Afrika Korps forward observation post in the Western Desert (hence the title for this episode).

A couple of years ago Gordon visited Bletchley Park with two leading codebreakers and a musician, as one does. Bletchley Park is where the British codebreakers were based in World War II, the codebreakers who cracked the German Enigma code. We ended up having dinner with the tour guide, a fascinating man who told a lot of stories that aren’t part of the standard tour.

One of those stories was about a German observation post during the North African campaign – Rommel and the Afrika Korps, Montgomery and the Desert Rats, the battle of El Alamein, and all the other legendary names from that struggle. This observation post was a story on a different scale, just a few men in an outpost in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by empty desert where every day was as quiet as the day before and the day after.

It would make a great movie, if it had the right scriptwriter, because there was a reason that those soldiers’ lives were so uneventful while they were in that post. The reason was that Allied troops were under strict orders to leave them completely alone. Why? Because the Bletchley Park codebreakers loved them, for the predictability of their reports. Every day, those soldiers dutifully sent in their reports to base, using the Enigma code system. And every day, they dutifully reported the same thing, that nothing was happening. Which meant that as long as those soldiers were left safely undisturbed, the Bletchley Park codebreakers knew what those daily reports would say, so whenever the Afrika Korps changed the settings on its Enigma machines, the Bletchley Park people could simply work backwards from the observation post’s reports, and crack the new settings.

Did those soldiers ever find out that their dutiful reports changed the course of history? How would they have felt about it if they had known the truth? We don’t know. For the right scriptwriter, it could make a deeply insightful movie about truth and war and a whole batch of other things. For us, it’s the motivation for collecting together the solutions to the worked examples in D’Agapeyeff’s book.

A body of text like this is known as a corpus, plural corpora. Corpora are typically useful for two reasons.

One is the words within the corpus. If you know what the individual words are in a corpus, then you can use those to work backwards towards possible solutions for a ciphertext. In the case of the German forward observation post, the Bletchley Park codebreakers knew that the daily reports would be along the lines of “All quiet, nothing to report”. There are only so many ways that you can phrase that message, and most of them will include the word “quiet” and/or the word “nothing”. In the more famous case of the German Kriegsmarine, the U-boats would routinely send in weather reports, where the Bletchley Park codebreakers would know what the weather was in the areas where the U-boats were operating, and could therefore work backwards from that.

Another use for a corpus is working out the relative frequencies of different letters within the corpus. This type of frequency analysis has been a standard method among codebreakers since it was first described by Al-Kindi in the 9th century. Al-Kindi isn’t exactly a household name today, but he’s been famous among codebreakers for centuries. For example, the sixteenth century polymath cryptographer Girolamo Cardano, who invented the Cardan grille cipher method, was familiar with the work of Al-Kindi, and thought he was one of the greatest intellects of the Middle Ages.

For ordinary English texts, the most commonly occurring letters are so well known that they have their own phrase, etaoin shrdlu. It’s occasionally used as an in-joke in publishing and related fields.

For some specialist areas, however, the letter frequencies are different, which has implications for codebreaking. Telegraphic English, for instance, typically leaves out a and the where possible, which affects the frequency distributions.

So, that’s the background to today’s article. The next section contains our current draft of the corpus of solutions that D’Agapeyeff used in the first edition of Codes and Ciphers. It’s a prefinal draft of a work in progress, so there may be some minor errors in it, but it gives a good general overview of the type of language he uses. His language is mainly military, and often telegraphic, with one or two excursions into famous historical examples. Some examples are incomplete or partially gibberish, for instance because they show a partial decipherment in progress. Here’s an example of that.

One interesting point about this example is that it uses plaintext in French. That’s perfectly reasonable in a book about codes – the reader needs to get used to cracking codes written in a foreign language. However, it raises the question of whether the plaintext for the D’Agapeyeff Cipher might be in a language other than English. We’ll return to that question in episode 6.

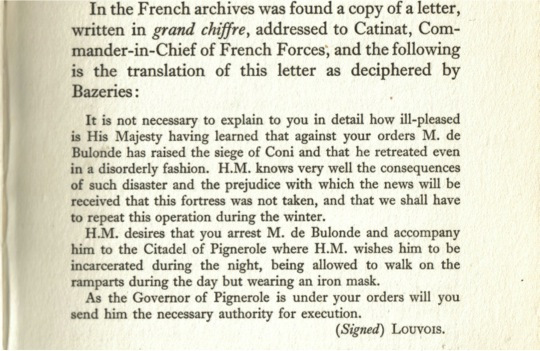

Another of his examples was originally written in French, and is famous in codebreaking circles; he shows it in English translation.

If you’re wondering about the mention of the man in the iron mask – this solution is from a real historical ciphertext, the Great Cipher, referring to events that really happened, and it has been suggested that de Bulonde was The Man in The Iron Mask. Similarly, D’Agapeyeff uses the phrase “the enemy” several times, which may be a deliberate allusion to the corresponding French phrase that the French codebreaker Bazeries used as the way in to crack the Great Cipher.

The Great Cipher quote is the longest text in the corpus, and D’Agapeyeff’s phrasing is different from the Wikipedia phrasing. Among other things, the D’Agapeyeff version has “Coni” where Wikipedia has “Cuneo”. These issues will re-surface in a later article in this series, with regard to possible insights into what text the D’Agapeyeff Cipher might contain, and whether it might be possible to work back from those possibilities.

Our strategy is to get the overall picture of our D’Agapeyeff work published soon in these blog articles, and then to put a collated final version onto the Hyde and Rugg website when we upgrade the website. For the corpus, we’re producing a properly annotated document that explains the context of each solution – for instance, the NKOY example below relates to African talking drums, and in the solution that refers to “aeroplane(s) defence” there’s a reference on the next page to the different phrasing “aerial defence”. Since D’Agapeyeff shows partial solutions and makes comments in the text of some solutions, producing a corpus of his solutions isn’t a simple case of typing in the words; the surrounding context needs to be included. However, the corpus below should be enough to give readers a reasonable idea of the types of text that D’Agapeyeff uses.

In next week’s thrilling episode, Gavin finds a significant typo. Who needs Indiana Jones movies when you can have real life?

The corpus (the page number is shown for each solution; some solutions occur across several pages during worked examples)

P28 Do not use bearer

P35 Food supplies running out

P43 Letter sent to the emperor giving full details

P47 It is not necessary to explain to you in detail how ill-pleased is His Majesty having learned that against your orders M. de Bulonde has raised the siege of Coni and that he retreated even in a disorderly fashion. H.M. knows very well the consequences of such disaster and the prejudice with which the news will be received that this fortress was not taken, and that we shall have to repeat this operation during the winter.

H.M. desires that you arrest M. de Bulonde and accompany him to the Citadel of Pignerole where H.M. wishes him to be incarcerated during the night, being allowed to walk on the ramparts during the day but wearing an iron mask.

As the Governor of Pignerole is under your orders will you send him the necessary authority for execution.

(Signed) LOUVOIS

P50 Re-union to-morrow at three p.m. Bring arms as we shall attempt to bomb the railway station. Chief

P63 NKOY

P68 King Henry the 8th was a Knave to his Queen

P86 GALLANTLY and FURIOUSLY he fought AGAINST the foe at WATERLOO.

IVY creeping along the ground suggests HUMILITY

The JURISDICTION of the NOBLE LEGISLATOR was offensive to the BARBARIAN.

A PHOTOGRAPHER saw SEVERAL KANGAROOS on the MOUNTAIN

I will arrange for (CC) XYKCD MQRAD GVK (CC) and after that (CC) XZALG MSAQW QAL (CC) Instructions requested.

PP111-112 I will arrange for (CCFI) 23301 89972 41 (CC) and after that (CCFI) 29330 61100 465 (CC) Instructions requested

P117 ENEMY ATTACKS AT DAWN

P118 ENEMY ATTACKS

P118 ENEMYATTACKSATDAWN

P121 Hold your brigade in readiness to move

P124 Advance brigade to-morrow

P126 Meeting brigade village cross roads

P134 ‘Le prisonier est mort – il n’a rien dit’ (‘The prisoner is dead; he has said nothing.’)

P138 -141 General ordered the second brigade to attack at 3.30 A.M. the third brigade one hour later the fourth keep in reserve

P145 The new plan of attack includes operations (EA) (BE) those (EA)o(AD) (EA) I s (DE)u(AB)ions over (BA)actor(BE) are(BE)a south west o? the river.

P146 No one here has deciphered the three latest dispatches, please discontinue these ciphers as the ones used hitherto were better.

P152 The third battery to take up north position

PP154-156 The reconnaissance of the route to the sea has revealed that the aeroplane(s) defence was over the town

Notes

Previous episodes:

For more about letter frequencies in codebreaking, the Wikipedia page is a good introduction:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etaoin_shrdlu

There’s more detail in Wikipedia here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_frequency

Wikipedia also has an article about Al-Kindi, who first described the frequency approach to codebreaking:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Kindi

For de Bulonde and the Iron Mask:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Cipher

August 9, 2013

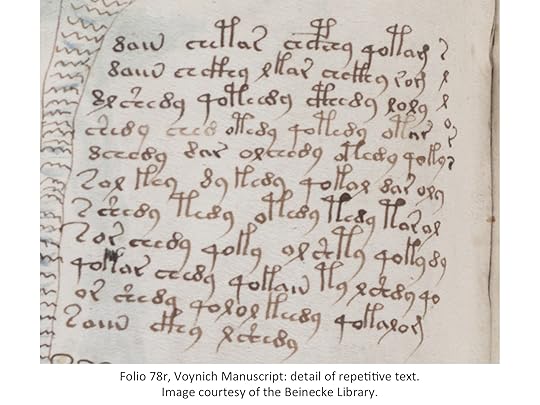

Hoaxing the Voynich Manuscript, part 3: The hurdle of expert linguist scrutiny

By Gordon Rugg

In this series of articles, we’re imagining that you’ve gone back in time, and that you want to produce the Voynich Manuscript as a hoax to make money.

The first article looked at why a mysterious manuscript would be a good choice of item to hoax. The second article looked at some of the problems involved in hoaxing a text that looked like an unknown language, from the linguistic viewpoint.

We’ll now look at a second set of linguistic problems that you’d face. These problems involve the standard ways that a linguist can try to make sense of an unknown language where there aren’t any related languages that can give any clues.

This is where the text of the Voynich Manuscript starts to look very much unlike any real human language.

This is one of those topics where you either need to go into huge detail and risk losing your readers, or where you need to do a short version and risk oversimplifying. I’ve gone for the short version for the time being. If there’s enough demand for more depth, I’ll revisit this in more detail later.

I’ll start by looking at how easy or difficult it would be to for a hoaxer to fool an expert in linguistics at the time when the manuscript appeared, in 1912, if the hoaxer was trying to make the Voynich Manuscript look like a genuine text in an unknown language. Then I’ll compare that with the situation in the 1580s (when Rudolph II bought the manuscript) and in the fifteenth century (the apparent date of the manuscript stylistically, and the date from the carbon testing)

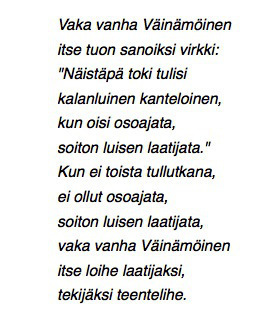

I’ll illustrate the process by using some text from a real language which will be unfamiliar to most readers, and by comparing and contrasting the linguist’s likely assessment of that text against their assessment of the text in the Voynich Manuscript.

How would a linguist in 1912 approach this, if they didn’t know the language? By 1912, linguistics (the scientific study of language) was being formalised as a new discipline; before that, there was over a century of solid work on historical linguistics and comparative linguistics, as we’ll see in the analysis below.

The 1912 linguist would immediately notice that it looks like a poem. It has short lines of roughly the same length; that’s a widespread convention in written poetry.

The reason I’ve used a poem as an example is that there have been occasional suggestions that the Voynich Manuscript might be a poem. That suggestion doesn’t stand up well to detailed examination, but there is one odd feature of the manuscript that’s relevant. In the Voynich Manuscript, the written line doesn’t behave like a simple division of the text to fit within the margins of the page; instead, the written line has some odd regularities. We’ll look at this issue again in more detail in later articles.

It would be clear to our 1912 linguist, though, that the Voynich manuscript wasn’t a poem in any traditional interpretation of the word. Its lines don’t end with pairs of the same syllables in end-rhyme (like “are” and “star” rhyming at the end of the first two lines of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star”). It doesn’t show systematic use of scansion, or metre, or of alliteration, or of a whole range of other features that are ubiquitous across different styles of poetry in different cultures. It’s not a poem.

Punctuation

Our linguist would notice that the text above has punctuation, whereas the Voynich Manuscript doesn’t. They’d decide, correctly, that this isn’t a big issue. Punctuation is a relatively modern concept; a lot of old texts don’t bother with it.

Accents and diacritics

Another obvious feature is that the text above has pairs of dots over some of the vowels, but no accent symbols or other diacritics. This implies that it probably isn’t a tone language. The Voynich Mansucript uses one type of possible diacritic, a swirling symbol like a large comma. It only occurs over the character transcribed as “ch” in the most widely used transcription of Voynichese.

If the Voynich Manuscript was written in some form of Chinese, as has occasionally been suggested, then we would expect to see a lot of indicators of tone, since Chinese is a tonal language. Here’s an example from Wikipedia of a Chinese tonal tongue-twister, showing the range of diacritics needed to show the different tones in Chinese.

Pinyin (Chinese): māma mà mǎ de má ma?

However, we don’t see any indication of that in the Voynich Manuscript.

Capitalisation and proper nouns

A third obvious feature is that some of the words in the text above start with an uppercase letter. One, Väinämöinen, is in the middle of a sentence, so it’s probably a proper noun – the name of a person or place or tribe, for instance. There’s another, Näistäpä, which comes after a colon, so the uppercase N might be just a convention of punctuation; however, like Väinämöinen it has a lot of pairs of dots over its vowels compared to all the other words in the text, so it might be another proper noun.

Linguists are very well aware that proper nouns often stay unchanged for a very long time indeed; for instance, the name “Alexander” is probably at least three thousand years old. There’s ancient Hittite royal correspondence that refers to someone called Alaksandus who might just be the same person as Helen of Troy’s lover in the Iliad (his usual name Paris was just his nickname; his real name was Alexandros). The result of this conservatisim is that proper nouns in a language are often linguistically different from ordinary common nouns in that same language. That might be what’s going on in this example.

This is relevant to a couple of features of the Voynich Manuscript. One is that the pages with pictures of plants each begin with a unique first word, as if it’s the name of the plant being shown on that page. These first words are different in structure from the other words on the page. This is consistent with what you’d see in a real language. It doesn’t prove that the manuscript is in a real language, though, since this feature is low-hanging fruit for a hoaxer.

The second feature involves some of the more flamboyant characters in the manuscript’s text. It’s been suggested that these are the equivalent of uppercase characters at the start of a proper noun or of a paragraph, in the same way that many illuminated manuscripts use elaborate illumination of the first letter in a page or paragraph. This is also consistent with what you’d see in a real language. It’s also consistent with what a sensible hoaxer would do, but that’s another story. We’ll return to this later.

Linguistic features

When our linguist looks at the words within a line of the text above, then they’d start seeing regularities; there’s a strong tendency for words within a line to start with the same consonant, particularly v, l and k.

This may be alliteration, which was a feature of early Germanic poetry. However, the language of this poem doesn’t look like Germanic, since it doesn’t contain any of the common words of Germanic, the equivalents of “the” and “a” and “he”.

Another regularity in the text is that within a word, there’s a tendency for the same vowels to occur across different syllables, as in vaka vanha. That may just be a poetic convention similar to the alliteration, but it may be a result of vowel harmony, which occurs in various languages scattered across the world.

By this stage a linguist in 1912 would be reasonably confident that they were dealing with a real language, and would have a shrewd suspicion of which language they were dealing with, even if they’d never encountered that language before. They wouldn’t be getting the same feeling about the Voynich manuscript text.

Word clusters

Our 1912 linguist would also be looking for examples of words repeatedly occurring together, as in vaka vanha. Those two occur together twice, both times before Väinämöinen. Since we’re dealing with poetry, there’s a fair chance that they’re a standard formulaic description of a person or place. Ancient epic poetry used these a lot – for instance, Diomedes is described as “Diomedes of the loud war-cry” and Hector is described as “Tamer of horses”.

These are not the only words to occur as a cluster; there’s also soiton luisen laatijata, where the same three words occur as a cluster in two separate lines.

That’s perfectly normal in human languages; you’ll routinely see phrases where the same two or three words occur together. In English, for instance, whenever you see the words on top together in the middle of a sentence, you’ll expect the next word to be of, since the phrase on top of is a standard phrase in English.

If you’re a linguist, this is starting to give you some clues towards the structure of the language. For instance, the text above has clearly separate words; not all languages do, since some will string together multiple syllables so that the distinction between traditional word, phrase and sentence is blurred. That’s one of the many things that linguistics students find strange on first encounter. There is something a bit like that effect in English, with words such as ungentlemanliness, which combines several elements together into a single word, including two words that can occur on their own (gentle and man).

This is one of many places where the text of the Voynich Manuscript diverges sharply from known human languages. It doesn’t contain this sort of clustering, where particular words tend to occur together with each other. Yes, there’s a tendency for some Voynichese words to be a bit more likely to occur on a page where a particular other Voynichese word occurs, but that’s an effect so weak that you need heavy-duty statistics to detect it; that’s nothing like the standard phrases you get in real human languages, where pairs or triplets of words routinely occur together. That absence is extremely odd.

Syllable structures

Picking up the theme of syllable structures, there are strong indications of regular syllable structures within the text, such as the pairs below.

virkki toki

kalanluinen kanteloinen

osoajata laatijata

laatijaksi tekijäksi

These might be indications of grammatical regularities, like Latin conjugations and declensions. They’re happening at the ends of the words, not at the start. Most Indo-European languages do that, but there are exceptions, such as the grammatical mutations in Celtic languages, which are why Irish spelling looks so eventful; it’s dealing with mutations in a way that’s perfectly sensible once you understand the grammar. By this stage, the linguist would have a pretty good idea of what the language of the poem is.

Again, the Voynich Manuscript’s text doesn’t show any clear regularities, even though it has a clear syllable structure. Voynichese words can contain any or all of three syllable types: prefix, root and suffix. That’s unusual. The reason it’s unusual is that Voynichese words can consist of a prefix and a suffix without any root between them – the equivalent of an English word like “uning” where “un” is a perfectly ordinary prefix, and “ing” is a perfectly ordinary suffix. There would be nothing very odd grammatically about a word like “unsee” or “seeing” where the prefix or suffix is combined with the root “see”. However, Voynichese has no such constraints. That’s very odd.

Small words

The poem above contains several small words – kun, ei and itse. Linguists like small words. The most common words in a language are usually small words, and they’re usually words like a or the or she or is. As a result, they can usually let you start making some educated guesses at the overall structure of what’s being said. It’s a bit like a crossword, where you’re guessing that a sentence says “something something is the something of the something”.

As you might have guessed by now, you don’t see this in Voynichese. It doesn’t have the pattern of very common, very short words between clusters of longer words.

The words themselves

Yet another area where the Voynich Manuscript is odd is in the words themselves. Usually a linguist looking at a decent-sized text can spot regular correspondences between some of the words in that text, and comparable words in a related language. For instance, there’s a regular pattern for Germanic languages to have an “f” at the start of a word where the corresponding Latin word has a “p”. If we take the Latin word pater and apply this pattern to it, we get fater, which is pretty close to German Vater and to English father. A key point here is that this is about large-scale regularities, not coincidental similarities between a few individual words. Again, there’s nothing like this in Voynichese.

Yet another issue with the words is that they don’t show the patterns you’d expect from text in a real language, especially text that bears some relationship to the illustrations on the same page. Here are a couple of examples of text from Culpeper’s Herbal.

Descrip. — This tree seldom groweth to any great bigness, but for the most part abideth like a hedge-bush, or a tree spreading its branches, the woods of the body being white, and a dark red cole or heart; the outward bark is of a blackish colour, with many whitish spots therein; but the inner bark next the wood is yellow, which being chewed, will turn the spittle near into a saffron colour. The leaves are somewhat like those of an ordinary alder-tree, or the female comet, or Dog-berry tree, called in Sussex dog-wood, but blacker, and not so long: the flowers are white, coming forth with the leaves at the joints, which turn into small round berries first green, afterwards red, but blackish when they are thoroughly ripe, divided as it were into two parts, wherein is contained two small round and flat seeds. The root runneth not deep into the ground, but spreads rather under the upper crust of the earth.

Descrip. — It being a garden flower, and well known to every one that keeps it,

I might forbear the description; yet, notwithstanding, because some desire it,

I shall give it. It runneth up with a stalk a cubit high, streaked, and somewhat

reddish towards the root, but very smooth, divided towards the top with small branches,

among which stand long broad leaves of a reddish green colour, slippery; the flowers

are not properly flowers, but tufts, very beautiful to behold, but of no smell, of

reddish colour ; it you bruise them, they yield juice of the same colour; being

gathered, they keep their beauty a long time: the seed is of a shining black colour.

From: http://archive.org/stream/culpeperscomplet00culpuoft/culpeperscomplet00culpuoft_djvu.txt

In both these sections, you see the same words occurring repeatedly: flower, divided, root, seeds. That’s just what you’d expect to see in a herbal, which by definition deals with plants and their parts, but you don’t see this pattern in the Voynich Manuscript pages with illustrations of plants. If the text in the manuscript really did relate to what was in the illustrations, you’d expect to see some words occurring frequently in the pages with illustrations of plants, but not as frequently in the pages with illustrations of zodiacs. You’d then expect to start spotting regularities within each page, like the way that the Culpeper descriptions mention size first and seeds last. But you don’t see any patterns like that in the Voynich Manuscript text. It’s yet another odd, major absence.

The 1912 summary

By this point, the 1912 linguist would have decided that the poem above is probably in Finnish or a related language. They’d be right; it’s a short extract from the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala.

They’d also have decided that Voynichese is very, very different from any known real language. They’d be right about that, even without the statistical evidence that shows other ways in which Voynichese is very different. Those differences aren’t just accidental differences that could be explained away as the result of Voynichese being a language from a very different language family. The short common words in particular are short for a reason; they get used a lot, and they get worn down like pebbles in a stream. You see the same effect of short common words across completely unrelated language families; it’s a product of cognitive economy, not of linguistic descent. For a real language not to show patterns like this would be extremely odd. Whatever we’re seeing in the Voynich Manuscript, it certainly doesn’t look like a language, and it doesn’t look like a language ought to look.

The 1580s summary

There wouldn’t be a linguist available to assess the text above or the Voynich Manuscript in the 1580s, since at that time linguistics as a discipline was far in the future. There would, though, be plenty of people who spoke more than one language, since intellectuals at the time would routinely learn Latin, and there would be a fair number of intellectuals who spoke a non-Indo-European language, either Hebrew or Arabic.

However, the tests they could apply to either the poem fragment above or to Voynichese would be very limited. They would be able to spot that the poem fragment was a poem, and in a language that probably used suffixes in much the same grammatical way that Latin does; they would spot that Voynichese was very different from any language that they knew. They wouldn’t know, however, just how odd Voynichese is.

Another potentially significant piece of context was that in the 1580s, the New World had been discovered, and the great voyages of exploration were taking place. The explorers were discovering civilisations and languages very different from anything previously suspected by Europeans. Against that backdrop, a book in an exotic language would be something that an educated would-be buyer would be mentally prepared for. Interestingly, though, the illustrations in the Voynich Manuscript are very un-exotic; there are no scenes of fabulous cities or flamboyantly-clothed kings and queens, no hint of influence from sources such as the Aztec books encountered by Spanish explorers and conquerors. The image below is from one of the handful of those books that escaped destruction by the Church; it’s known as the Dresden Codex, after the city where it is now kept.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dresden_codex,_page_2.jpg

The Voynich Manuscript, instead, has just odd plants, and strange scenes of naked women in weird baths, and slightly unusual zodiacal diagrams. Strange, yes, but looking overall like a European mediaeval book, not like a journal of some amazing journey to far-away exotic lands, or a book brought back from one of those lands.

The 1400s summary

The summary for the 1400s is similar to the one for the 1580s, except that the New World wasn’t discovered till 1492, very near the end of the century. That doesn’t mean, though, that the European scholarly world was insular and benighted. There had been long-distance trade for centuries; for instance, when William of Rubruck visited the Mongol Khan in 1253, he found that there were already several other European visitors there, as a quite routine feature of Mongol court life. Overall, though, the level of linguistic scrutiny at this time would be far lower than in 1912.

Conclusion

So, if you were a would-be hoaxer, and you were thinking of producing something that looked like a book in an unknown language, what sort of examination would you expect it to face at three key points in history?

The short answer is that the scrutiny in 1912 would be much better informed and much more searching than the scrutiny would be in either the 1580s or the 1400s. In consequence, producing a plausible hoax of an unknown language would be a lot more difficult and potentially expensive in 1912. That wouldn’t necessarily be a show-stopper. For someone hoaxing just to make money, the key question is the likely return on investment, not the initial cost of that investment. However, the harder scrutiny would increase the chance of the book failing to pass scrutiny by the would-be buyer’s assessors.

I think, therefore, that it’s plausible that a hoaxer in the 1400s or 1580s might try to make the Voynich Manuscript look like an unidentified language. I don’t think that a hoaxer around 1912 would try to do that, if they had any sense. Around 1912, it would be a much safer bet to make it look like an uncracked code.

Interestingly, Voynich almost immediately started working on the assumption that the Voynich Manuscript was a coded text by Roger Bacon, rather than an unidentified language. There’s just too much that’s strange about the text of the Voynich Manuscript for serious linguists to believe that it could be an unidentified language. The Voynich Manuscript could have masqueraded as an unknown language pretty easily in the 1400s or 1500s, but in Voynich’s time, the “unknown language” explanation was shot down almost immediately. That left the hoax explanation and the code explanation as the two main contenders, and at the time, nobody could see a way of hoaxing the strange regularities that occur throughout the manuscript, so the code explanation emerged as the leader by default.

In the next episodes, we’ll see some of the problems with hoaxing something that looks like an unknown code, and we’ll see how strange regularities can arise as unintended side-effects of a simple hoaxing mechanism.

Notes

Translation of the Kalevala fragment used in this article:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalevala

Background context: I’m posting this series of articles as a way of bringing together the various pieces of information about the hoax hypothesis, which are currently scattered across several sites.

Quick reassurance for readers with ethical qualms, about whether this will be a tutorial for fraudsters: I’ll only be talking about ways to tackle authenticity tests that were available before 1912, when the Voynich Manuscript appeared. Modern tests are much more difficult to beat, and I won’t be saying anything about them.

August 8, 2013

Tweet-sized thought for the day: Pattern matching, serial processing, politicians and word salad

Pattern matching is an easy way to check if a thing looks right. Serial processing is a hard way to check if it is right. A big difference. hydeandrugg.wordpress.com

There are two computational mechanisms for solving a problem, regardless of whether you’re a human or a computer. One of these mechanisms is parallel processing, where you carry out lots of tasks at the same time; this mechanism is very good for pattern matching, where you identify patterns (whether physical patterns, or underlying regularities in events, etc). The other mechanism is serial processing, where you do one task at a time; slow, but steady, and much better for catching errors in reasoning.

Humans are very good at pattern matching, which we find swift and easy, and very bad at serial processing, which most of us find slow and painful. So what? So this is why we appear to be an illogical species, and why demagogue politicians can get so far despite having policies that are little more than word salad.

Pattern matching is fast, easy for us to do, and lets us solve a lot of everyday problems (like crossing the road) that are extremely difficult to handle via serial processing.

That’s fine if you’re crossing the road, or recognising the person that you’ve just met. However, it’s not fine if you’re trying to follow a chain of reasoning, whether it’s a legal argument or the assembly instructions for something you’ve just bought. For the chain of reasoning, you need to use serial processing, which human beings find difficult, slow, and hard work.

So there’s a strong temptation to use pattern matching for tasks like assessing what a politician has just said, as a quick, easy approach – even if it gives the wrong result sometimes. Politicians learned this a long time ago, and populist politicians are very good at producing word salad, which doesn’t actually make any sense when you examine it via serial processing, but which has all the right ingredients to look good if you only examine it via pattern matching.

The same mechanisms occur across a huge swathe of human activity. The distinction between them is important. Once you start doing that right, then you can start dividing tasks up efficiently between humans and computers, since we and they have complementary strengths and weaknesses. The Search Visualizer software is one example of how that can work in practice – humans are slow readers in comparison to how fast they can scan patterns, so if you want to assess something quickly within a text, then it’s a good idea to translate that text into a format that you can handle via pattern matching.

There’s a more in-depth discussion of this in my book with Joe D’Agnese, Blind Spot: http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Spot-Solution-Right-Front/dp/0062097903

Some articles and links:

Notes

This is one of our series of Tweet sized thoughts. These are intended as a quick, effective way to publicise concepts that aren’t as widely known as they should be. We’re using this format rather than simply tweeting because it gives us a way to unpack the concepts in more detail, with examples, links and references if needed. We’re taking our usual approach of indicating useful related concepts in bold face where it’s easy to track down further information, and of only giving references where they’re not easy to find.

August 4, 2013

Tweet-sized thought for the day: Communicative and expressive behaviour

By Gordon Rugg

Expressive behaviour shows how you feel. Instrumental behaviour gets the job done. The balance matters. http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com

More detail

These two concepts are widely used in the social sciences.

Expressive behaviour shows how you feel.

Expressive behaviour is also known as communicative behaviour. Expressive behaviour shows people how you feel about something. Politicians use it a lot to signal that they care, and to show tribal allegiance. With expressive behaviour, the key point is to send out a signal about how you feel, regardless of whether you’re actually getting the original job done.

Instrumental behaviour gets the job done.

Instrumental behaviour is about getting the job done, regardless of whether anyone sees how you feel about it.

This isn’t an either/or choice. Sometimes a behaviour is highly expressive and also highly instrumental. A lot of legal test cases are highly expressive (the person bringing the case is signalling that they’re willing to risk huge legal fees or prison for their beliefs) and also highly instrumental (because if the person bringing the case wins it, then that will get the law changed in the direction that they want).

When you’re worn out and feeling miserable, it’s horribly easy to slip into expressive behaviour. That’s okay for some situations, but it’s not okay for others. A classic example is when you’re unable to find a new job, and you sink into a pit of misery. In this situation, you need to tackle the problem of job-finding via instrumental behaviour – for instance, by reading a book like What Color Is Your Parachute, to find other, more successful strategies.

The balance matters.

This doesn’t mean that instrumental behaviour is always better than expressive behaviour. It isn’t. They each have different purposes from the other. There are a lot of situations where expressive behaviour is far better than instrumental behaviour. Sometimes it’s more important to show the other person that you understand and that you care, rather than simply fixing the practical problem. A lot of tech support people hit problems with this, when they think that the key point is fixing the problem, but they’ve missed the importance of showing the customer that they care about how the customer feels. The concept of “It’s not about the nail” is highly relevant here. A lot of relationships hit avoidable problems because one partner wants expressive behaviour, and the other is offering instrumental behaviour.

So, getting the balance right between expressive and instrumental is a valuable skill. Once you’re aware of these concepts, you have a much better chance of getting that balance right, and getting a good outcome.

An example of this is What Color Is Your Parachute. It’s a book that changed my life. It’s about taking control of your life instrumentally by working out where you want to be, and finding the best way to get there. It’s also strongly ethical; it’s not about climbing to the top of the corporate ladder, but is instead about self-fulfilment and the route to where you really want to be. There’s a lot of Christian content which might irritate some readers, but that content is kept clearly separate from the instrumental material about jobs and careers.

One important feature is that this book is heavily based on evidence. That evidence is often surprising – for instance, the most common strategy for finding a job, namely looking in the job advertisements in the paper, is one of the least effective strategies.

This book comes out in regular updated editions, and is in most public libraries.

It’s available on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/What-Color-Your-Parachute-2013/dp/1607741474

There’s also a website supporting it: http://www.jobhuntersbible.com/

There’s a new book out by the same author: http://www.amazon.com/The-Job-Hunters-Survival-Guide-Rewarding/dp/158008026X

I haven’t read that yet, but if it’s as good as What Color, then it will be well worth getting.

Notes

This is one of our series of Tweet sized thoughts. These are intended as a quick, effective way to publicise concepts that aren’t as widely known as they should be. We’re using this format rather than simply tweeting because it gives us a way to unpack the concepts in more detail, with examples, links and references if needed. Please feel free to tweet these concepts if you wish.

We’re taking our usual approach of indicating useful related concepts in bold face where it’s easy to track down further information, and of only giving references where they’re not easy to find.

August 3, 2013

Design Rationale, part 1: A tale of reasons, raccoons and cat flaps

By Gordon Rugg

Often, a small example can give key insights into bigger, deeper questions. The saga of our cat flap is one of those cases. It’s an apparently trivial problem that leads swiftly into important, difficult questions like how to tackle design decisions, and how to identify design options that you might easily have overlooked, and how to spot design problems in the first place.

That’s how we ended up as one of the few the families in England to have a raccoon flap in their back door, rather than a cat flap. It’s an excellent example of design rationale – the reasoning behind a particular design decision. Like most problems involving design solutions to client requirements, it takes us into the difficult territory where human beings have trouble establishing just what they want and why they want it, and where designers are trying to find a way of tackling the problem that’s systematic but that can also capture the often messy requirements and constraints affecting a particular problem.

I’ll tell the cat flap story first, and then work through the insights that it gives about design rationale.

The saga begins with our two cats, Pom and Tiddles (names changed to protect the frequently guilty). They like to spend some time in the garden, and some time in the house, so we installed a cat flap to make life easier for everyone involved.

Design 1: The ordinary cat flap

For years, we had a simple, cheap, low-tech cat flap that worked perfectly well. Then trouble arrived, in the form of a tomcat nicknamed Burglar Cat that started coming in through the cat flap and causing trouble.

Design 2: The magnetic cat flap

The novelty of cleaning up after a visiting tomcat soon wears off, so we bought a more expensive new cat flap with a magnet sensor and a couple of magnetic collars for Tiddles and Pom. The magnetic cat flap had a deep entry tunnel. This caused problems. The hold for the cat flap was quite high off the ground. With the old cat flap, that hadn’t been an issue, because Tiddles and Pom could stand on their hind legs, got a hold on the cat flap, and climb up and in. With the magnetic cat flap, that didn’t work, because the entry tunnel was deep and slippery, without anything to hold on to. So we installed a cat step on the back door as an allegedly temporary fix.

The new magnetic cat flap worked for a while, until the tomcat found a way of getting through it, even though he didn’t have a magnetic collar. We suspected it was because the cat flap didn’t always close completely after Pom came through. We bought yet another cat flap.

Design 3: The microchip cat flap

This cat flap was more expensive and higher tech than the magnetic one. Fortunately, it had almost identical dimensions to the magnetic one, so we were able to install it without problems. Everything went well for a while, until Burglar Cat started breaking in again. We couldn’t work out how he was managing it. Eventually, we caught him in the act. The cat flap was extremely efficient at stopping cats from pushing forward into the house. It wasn’t quite so efficient at stopping cats from pulling the flap outward. Burglar Cat had found a way of hooking his claws under the flap and pulling it open. It took a lot of effort on his part, and he did a lot of angry growling in the process, but he managed to open it eventually.

We phoned the manufacturers, who were brilliant. They listened carefully, asked insightful questions, and said they would send us an even higher tech solution. It arrived a few days later. Here’s what it was.

Why a raccoon flap? With hindsight, it makes perfect sense. Manufacturers think about markets, and the North American market is big. The North American market has some requirements that the European market doesn’t have, such as being able to keep out raccoons, which have nimble fingers and are extremely good at breaking in to places where they’re unwelcome. Anything able to keep a raccoon out should also be able to keep a cat out. So, it makes sense that the manufacturers of high-spec pet flaps would produce a raccoon flap, and it makes sense that they would send us one to solve our Burglar Cat problem.

At time of writing, the raccoon flap is working perfectly, and everyone involved is happy, except for Burglar Cat. (Reassurance for any readers who are wondering if he’s a sad, hungry stray: Burglar Cat is a very well fed, well-groomed brute, who is clearly much loved by someone, and who probably gets a huge number of extra meals via his burglaries of homes with lower-tech cat flaps.)

So, that’s the story of why we’re probably the only family in Shropshire with a raccoon flap in the back door. What does it tell us about design rationale?

Design rationale: The key concepts

One important point to flag from the start is that there was nothing actually wrong about the first cat flap. It did its job perfectly well for years, until the situation changed.

That takes us into several concepts at the interface between consumer choice and design decisions.

Optimising and satisficing

This is a concept from the work of Herb Simon on decision making.

For some decisions, you’re looking for the best possible solution. That gets you into a complicated problem where you have to identify all the relevant potential solutions, and then identify all the relevant factors, and then decide how to attribute scores to all of the relevant potential solutions so you can work out which one is best. Simon called this process optimising. It’s usually difficult, and usually requires a lot of time and effort, and usually you can’t guarantee that the solution you find is truly optimal.

For other decisions, you’re looking for a solution that’s good enough, but that doesn’t have to be the best possible. Simon called this process satisficing (with a c – that isn’t a typo). With these decisions, you decide in advance what will be good enough, and then you choose the first option you meet that meets those criteria. There may be better solutions available, but for your purposes, that doesn’t matter. In cases of satisficing, you’re saving time and effort by choosing the first good-enough solution, and you’re making a conscious decision that those savings will more than outweigh the potential losses if there’s a better solution that you’ve missed.

For our first cat flap, we made a satisficing decision, and it worked well for years, until the situation changed. For satisficing decisions, you can use a range of methods from decision theory and from requirements engineering to identify the essential needs.

If you’re optimising rather than satisficing, then you need to think about how to compare the possible choices. That takes you into concepts like measurement theory, which I’ll probably cover in a later article, and Multi-Criterion Decision-Making, which is described below.

Multi-Criterion Decision-Making

This is a popular, simple and usually effective way of choosing the best solution out of several candidates. It’s useful not only to customers, but also to designers faced with several possible solutions.

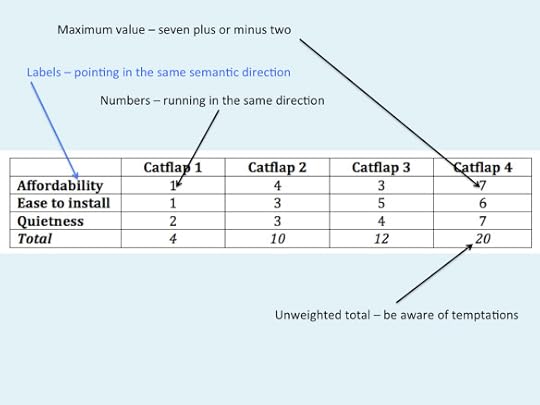

The usual way of doing it is to open a spreadsheet, and to give each candidate a column, and to give each relevant attribute a row. You then give a score for each candidate on each attribute, and total the scores for each candidate, then choose whichever gets the highest score. Here’s a mocked-up example. It shows pretty clearly that the first cat flap was the best choice when security wasn’t an issue, but when we were up against extreme cat proofing problems, then the fourth cat flap (i.e. the raccoon flap) was the best choice. (It’s usually a good idea to use neutral names for the items being compared, rather than manufacturers’ brand names that are designed to predispose you towards a good opinion of the product.)

I won’t go into much detail about this approach, since it’s widely known, but I’ll mention a few classic points of detail that can make the difference between using it well and using it badly. The diagram below shows the points in question.

The numbers in the cells should normally be on a scale from one to seven, plus or minus two. If you use ten point scales, then people’s ratings are less consistent than if you use a scale of about seven points. This is due to a classic limitation of human working memory, first described in Miller’s 1956 paper on the magical number seven, plus or minus two.

The names of the attributes should all be phrased in such a way that the meaning of a high score is consistent. For instance, the first attribute is currently affordability, so a high score is good. If that same attribute had been called cost, then there would be confusion about whether a high score meant high cost (because of the high number), or low cost (because a high score is good).

The numbers in the cells should all run in the same direction – usually low being bad, and high being good. Also, watch out for the risk of including numbers that aren’t ratings, such as the dollar price of an item; this would completely mess up the calculation of the total.

The totals in this example are from unweighted values. In this example, we’re simply adding the numbers together. Often, though, one attribute will be more important than the others, so you might want to give it a weighting – for instance, by doubling its raw score, so that a raw score of 5 is doubled to a score of 10 in the cell. This is perfectly legitimate if done honestly, but cynical users have been known to decide in advance which of the candidate solutions they want, and then to add weighting factors to the attributes until the spreadsheet produces the answer that they want.

That covers some of the background concepts; we’ll now start on the core concept of this article, namely design rationale itself.

Design rationale

Design rationale is about the reasons for a design choice. This leads into a lot of topics that look messy, but that can often be made cleaner by using the right methods. As usual, there are methods available that are widely known in some fields but almost unknown in others, so I’ve pulled together a range of useful concepts from different fields for this article. I’ll discuss some of them in more depth in future articles.

We can illustrate the concept via some design annotation. This is a simple but effective way of showing the rationale behind each design feature. Here’s an example; it’s our raccoon flap.

Design rationale is well established in many fields of design, but there’s variation in how formally it’s applied.

With the design annotation approach, it’s easy to identify most of the design points and to explain the reasoning behind the solution chosen, which can be very helpful when communicating with clients. It’s also possible, particularly if you’re using ego-free design, to use this to identify places where you don’t have a stated rationale for a decision. For instance, in the cat flap diagram, is there a rationale for the breadth, width and thickness of the cat shelf?

In most fields there are standard constraints that every professional knows and (in theory at least) remembers to include in design decisions. Building regulations and human factors guidelines are two examples of this.

However, when you’re dealing with a large number of possible constraints (as in building regulations) then it’s very easy to forget one. This is also a potential problem if you’re dealing with multifaceted constraints. For instance, in mechanical engineering for medical implants, you have to consider the mechanical strength of the possible materials, and the toxicity of those materials, and the risk of chemical interactions between those materials.

This is where there’s potential for using approaches from other fields to provide new ways of handling the assorted problems that you need to tackle in large-scale design rationale. The sections below give some tasters on ways of doing this.

Complementary approaches

One approach that helps make sense of large quantities of design constraints is facet theory. You can organise those constraints in terms of e.g. the mechanical properties facet and the toxicity facet and the chemical interaction facet. That doesn’t solve all the problems, but at least it tidies them up neatly.

Moving further into the detail, with design rationale, you’re getting triplets of statements, of the underlying form [I did X] [in order to] [do Y].

That’s easily modeled within graph theory, and fits very neatly with laddering.

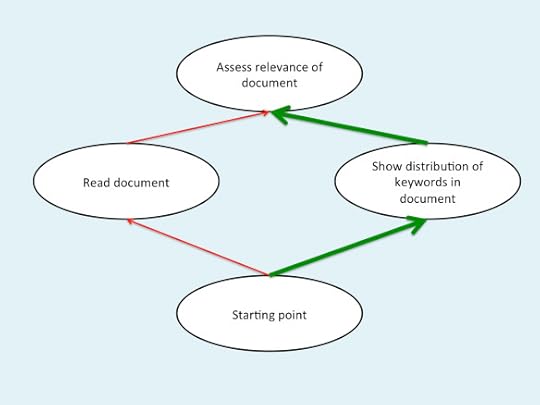

When you use this laddering in this context, you often get very interesting insights once you ladder up two steps. A typical pattern is that the first step looks sensible and obvious, but when you reach the second step, you discover that the client hasn’t thought about other paths that reach the same goal; instead, they’ve become fixated on that first step, and lost sight of the bigger picture. A good example of this is the Search Visualizer software. Clients wanted to read the documents as a step towards the higher level goal of assessing the relevance of the documents. However, they hadn’t realised that there was a much faster and easier way of assessing the relevance of the documents, by seeing the distributions of the keywords within each document.

The illustration below shows this diagramatically. The client’s usual route has a lot of disadvantages – it’s slow, and it’s difficult for users with dyslexia, and trying to use it on languages that you don’t speak will involve a huge amount of hassle even with automatic translation software. The Search Visualizer route has a lot of advantages in comparison.

What often happens in such cases is that the client is extremely pleased with the new approach, and immediately abandons the previous approach. This is where your development methodology makes a huge difference. With the traditional waterfall model of requirements handling, having the client drastically change their requirements in this way would cause chaos, even though it resulted in a much better solution. However, if you’re using an iterative approach, particularly one that starts with cheap, fast non-functional mockups, then this sort of change would probably occur within the first iteration, where you could easily and cheaply incorporate it into the next cycle of design, and acquire a happy client in the process.

In practical terms, you can catch a lot of these issues simply by asking “Why would you like that?” a couple of times to get the higher-level goal, and then asking “Can you tell me some other ways of achieving that goal?” once you’ve found what the higher level goal is. (Asking about “some other ways” is more likely to produce some ideas than asking about “any other ways” – sometimes apparently minor changes in the phrasing make a difference.)

This approach won’t always work – in the case of Search Visualizer, we worked out the other route ourselves – but it will catch a lot of cases. When the client doesn’t know an alternative route, then you can try other approaches yourself, such as constraint relaxation.

Constraint relaxation and creativity

Creativity is often treated as some sort of mystic impenetrable mystery, but it isn’t. In practice, it can be handled via two main routes, that correspond with the two computational processing routes of sequential processing and parallel processing.

That won’t mean much to most people, but you can get to the end point without needing to know the details of how the solutions work.

Constraint relaxation

One simple solution via sequential processing is to list all the constraints affecting a problem, one after the other. Here’s a hypothetical list.

Cat flap size constraints

Must be big enough to let any cat in

Must be small enough to keep out dogs

(etc)

What you now do is go through the list, one item at a time, asking yourself what would happen if you threw away that constraint.

Suppose, for instance, you throw away the constraint that the cat flap must be big enough to let any cat in. What happens then? Well, one thing you realise is that tomcats are usually bigger than female cats, so for some customers, like us, who have female cats and want to keep out a large tomcat, this might be a good solution. You could market a “small to medium sized” low tech cat flap where the size alone kept out the problem cat; this would let you solve the problem much more cheaply than by using electronics.

Deep structure pattern matching

Constraint relaxation works neatly and methodically, step by step. Deep structure pattern matching is very different. What you do in this approach is to let the human being do what human beings are very good at, namely seeing underlying patterns and similarities.

A simple and effective way of using this method is to tackle a problem by getting the team to look at lots of images of arbitrarily chosen objects and scenes – for instance, browsing a site like Pinterest.

What happens is that the designer’s subconscious eventually spots an underlying similarity between the image they’re viewing and the problem that they’re tackling. These similarities usually make sense in hindsight, but are very hard to predict in advance. With the Search Visualizer software, Ed de Quincey and I were discussing Roman magical word squares, such as the SATOR AREPO word square, when we realised the deep structure similarity between that and patterns of keywords in online search, that led us into inventing the Search Visualizer. That’s something of an extreme example, but it illustrates the underlying point.

Closing thoughts

That’s a brief introduction to the concept of design rationale. We’ll be returning to the theme of design repeatedly in later articles.

There are links below to a range of articles and sites that you may find useful.

Notes and links

Satisficing and optimising: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satisficing

Decision making approaches: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decision_making

Raccoons versus the raccoon flap: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjeoSqdKLto

Facet theory: http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/05/30/an-introduction-to-facet-theory/

Iterative design: http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/07/03/knowing-the-unknowable-revisited-why-clients-cant-know-their-requirements-and-some-ways-to-fix-the-problem/

Laddering: http://www.hydeandrugg.com/resources/laddering.pdf

The SATOR square: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sator_Square

The Search Visualizer (free online version): http://www.searchvisualizer.com/

The Search Visualizer blog: http://searchvisualizer.wordpress.com/

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers