Hoaxing the Voynich Manuscript, part 3: The hurdle of expert linguist scrutiny

By Gordon Rugg

In this series of articles, we’re imagining that you’ve gone back in time, and that you want to produce the Voynich Manuscript as a hoax to make money.

The first article looked at why a mysterious manuscript would be a good choice of item to hoax. The second article looked at some of the problems involved in hoaxing a text that looked like an unknown language, from the linguistic viewpoint.

We’ll now look at a second set of linguistic problems that you’d face. These problems involve the standard ways that a linguist can try to make sense of an unknown language where there aren’t any related languages that can give any clues.

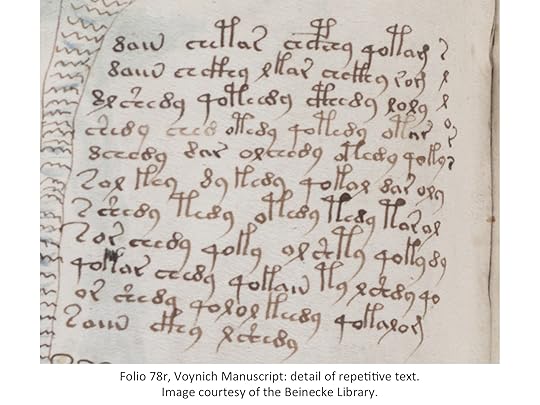

This is where the text of the Voynich Manuscript starts to look very much unlike any real human language.

This is one of those topics where you either need to go into huge detail and risk losing your readers, or where you need to do a short version and risk oversimplifying. I’ve gone for the short version for the time being. If there’s enough demand for more depth, I’ll revisit this in more detail later.

I’ll start by looking at how easy or difficult it would be to for a hoaxer to fool an expert in linguistics at the time when the manuscript appeared, in 1912, if the hoaxer was trying to make the Voynich Manuscript look like a genuine text in an unknown language. Then I’ll compare that with the situation in the 1580s (when Rudolph II bought the manuscript) and in the fifteenth century (the apparent date of the manuscript stylistically, and the date from the carbon testing)

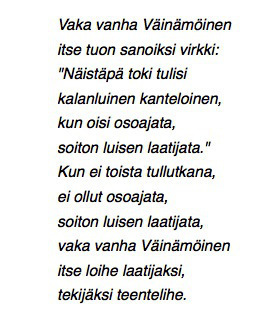

I’ll illustrate the process by using some text from a real language which will be unfamiliar to most readers, and by comparing and contrasting the linguist’s likely assessment of that text against their assessment of the text in the Voynich Manuscript.

How would a linguist in 1912 approach this, if they didn’t know the language? By 1912, linguistics (the scientific study of language) was being formalised as a new discipline; before that, there was over a century of solid work on historical linguistics and comparative linguistics, as we’ll see in the analysis below.

The 1912 linguist would immediately notice that it looks like a poem. It has short lines of roughly the same length; that’s a widespread convention in written poetry.

The reason I’ve used a poem as an example is that there have been occasional suggestions that the Voynich Manuscript might be a poem. That suggestion doesn’t stand up well to detailed examination, but there is one odd feature of the manuscript that’s relevant. In the Voynich Manuscript, the written line doesn’t behave like a simple division of the text to fit within the margins of the page; instead, the written line has some odd regularities. We’ll look at this issue again in more detail in later articles.

It would be clear to our 1912 linguist, though, that the Voynich manuscript wasn’t a poem in any traditional interpretation of the word. Its lines don’t end with pairs of the same syllables in end-rhyme (like “are” and “star” rhyming at the end of the first two lines of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star”). It doesn’t show systematic use of scansion, or metre, or of alliteration, or of a whole range of other features that are ubiquitous across different styles of poetry in different cultures. It’s not a poem.

Punctuation

Our linguist would notice that the text above has punctuation, whereas the Voynich Manuscript doesn’t. They’d decide, correctly, that this isn’t a big issue. Punctuation is a relatively modern concept; a lot of old texts don’t bother with it.

Accents and diacritics

Another obvious feature is that the text above has pairs of dots over some of the vowels, but no accent symbols or other diacritics. This implies that it probably isn’t a tone language. The Voynich Mansucript uses one type of possible diacritic, a swirling symbol like a large comma. It only occurs over the character transcribed as “ch” in the most widely used transcription of Voynichese.

If the Voynich Manuscript was written in some form of Chinese, as has occasionally been suggested, then we would expect to see a lot of indicators of tone, since Chinese is a tonal language. Here’s an example from Wikipedia of a Chinese tonal tongue-twister, showing the range of diacritics needed to show the different tones in Chinese.

Pinyin (Chinese): māma mà mǎ de má ma?

However, we don’t see any indication of that in the Voynich Manuscript.

Capitalisation and proper nouns

A third obvious feature is that some of the words in the text above start with an uppercase letter. One, Väinämöinen, is in the middle of a sentence, so it’s probably a proper noun – the name of a person or place or tribe, for instance. There’s another, Näistäpä, which comes after a colon, so the uppercase N might be just a convention of punctuation; however, like Väinämöinen it has a lot of pairs of dots over its vowels compared to all the other words in the text, so it might be another proper noun.

Linguists are very well aware that proper nouns often stay unchanged for a very long time indeed; for instance, the name “Alexander” is probably at least three thousand years old. There’s ancient Hittite royal correspondence that refers to someone called Alaksandus who might just be the same person as Helen of Troy’s lover in the Iliad (his usual name Paris was just his nickname; his real name was Alexandros). The result of this conservatisim is that proper nouns in a language are often linguistically different from ordinary common nouns in that same language. That might be what’s going on in this example.

This is relevant to a couple of features of the Voynich Manuscript. One is that the pages with pictures of plants each begin with a unique first word, as if it’s the name of the plant being shown on that page. These first words are different in structure from the other words on the page. This is consistent with what you’d see in a real language. It doesn’t prove that the manuscript is in a real language, though, since this feature is low-hanging fruit for a hoaxer.

The second feature involves some of the more flamboyant characters in the manuscript’s text. It’s been suggested that these are the equivalent of uppercase characters at the start of a proper noun or of a paragraph, in the same way that many illuminated manuscripts use elaborate illumination of the first letter in a page or paragraph. This is also consistent with what you’d see in a real language. It’s also consistent with what a sensible hoaxer would do, but that’s another story. We’ll return to this later.

Linguistic features

When our linguist looks at the words within a line of the text above, then they’d start seeing regularities; there’s a strong tendency for words within a line to start with the same consonant, particularly v, l and k.

This may be alliteration, which was a feature of early Germanic poetry. However, the language of this poem doesn’t look like Germanic, since it doesn’t contain any of the common words of Germanic, the equivalents of “the” and “a” and “he”.

Another regularity in the text is that within a word, there’s a tendency for the same vowels to occur across different syllables, as in vaka vanha. That may just be a poetic convention similar to the alliteration, but it may be a result of vowel harmony, which occurs in various languages scattered across the world.

By this stage a linguist in 1912 would be reasonably confident that they were dealing with a real language, and would have a shrewd suspicion of which language they were dealing with, even if they’d never encountered that language before. They wouldn’t be getting the same feeling about the Voynich manuscript text.

Word clusters

Our 1912 linguist would also be looking for examples of words repeatedly occurring together, as in vaka vanha. Those two occur together twice, both times before Väinämöinen. Since we’re dealing with poetry, there’s a fair chance that they’re a standard formulaic description of a person or place. Ancient epic poetry used these a lot – for instance, Diomedes is described as “Diomedes of the loud war-cry” and Hector is described as “Tamer of horses”.

These are not the only words to occur as a cluster; there’s also soiton luisen laatijata, where the same three words occur as a cluster in two separate lines.

That’s perfectly normal in human languages; you’ll routinely see phrases where the same two or three words occur together. In English, for instance, whenever you see the words on top together in the middle of a sentence, you’ll expect the next word to be of, since the phrase on top of is a standard phrase in English.

If you’re a linguist, this is starting to give you some clues towards the structure of the language. For instance, the text above has clearly separate words; not all languages do, since some will string together multiple syllables so that the distinction between traditional word, phrase and sentence is blurred. That’s one of the many things that linguistics students find strange on first encounter. There is something a bit like that effect in English, with words such as ungentlemanliness, which combines several elements together into a single word, including two words that can occur on their own (gentle and man).

This is one of many places where the text of the Voynich Manuscript diverges sharply from known human languages. It doesn’t contain this sort of clustering, where particular words tend to occur together with each other. Yes, there’s a tendency for some Voynichese words to be a bit more likely to occur on a page where a particular other Voynichese word occurs, but that’s an effect so weak that you need heavy-duty statistics to detect it; that’s nothing like the standard phrases you get in real human languages, where pairs or triplets of words routinely occur together. That absence is extremely odd.

Syllable structures

Picking up the theme of syllable structures, there are strong indications of regular syllable structures within the text, such as the pairs below.

virkki toki

kalanluinen kanteloinen

osoajata laatijata

laatijaksi tekijäksi

These might be indications of grammatical regularities, like Latin conjugations and declensions. They’re happening at the ends of the words, not at the start. Most Indo-European languages do that, but there are exceptions, such as the grammatical mutations in Celtic languages, which are why Irish spelling looks so eventful; it’s dealing with mutations in a way that’s perfectly sensible once you understand the grammar. By this stage, the linguist would have a pretty good idea of what the language of the poem is.

Again, the Voynich Manuscript’s text doesn’t show any clear regularities, even though it has a clear syllable structure. Voynichese words can contain any or all of three syllable types: prefix, root and suffix. That’s unusual. The reason it’s unusual is that Voynichese words can consist of a prefix and a suffix without any root between them – the equivalent of an English word like “uning” where “un” is a perfectly ordinary prefix, and “ing” is a perfectly ordinary suffix. There would be nothing very odd grammatically about a word like “unsee” or “seeing” where the prefix or suffix is combined with the root “see”. However, Voynichese has no such constraints. That’s very odd.

Small words

The poem above contains several small words – kun, ei and itse. Linguists like small words. The most common words in a language are usually small words, and they’re usually words like a or the or she or is. As a result, they can usually let you start making some educated guesses at the overall structure of what’s being said. It’s a bit like a crossword, where you’re guessing that a sentence says “something something is the something of the something”.

As you might have guessed by now, you don’t see this in Voynichese. It doesn’t have the pattern of very common, very short words between clusters of longer words.

The words themselves

Yet another area where the Voynich Manuscript is odd is in the words themselves. Usually a linguist looking at a decent-sized text can spot regular correspondences between some of the words in that text, and comparable words in a related language. For instance, there’s a regular pattern for Germanic languages to have an “f” at the start of a word where the corresponding Latin word has a “p”. If we take the Latin word pater and apply this pattern to it, we get fater, which is pretty close to German Vater and to English father. A key point here is that this is about large-scale regularities, not coincidental similarities between a few individual words. Again, there’s nothing like this in Voynichese.

Yet another issue with the words is that they don’t show the patterns you’d expect from text in a real language, especially text that bears some relationship to the illustrations on the same page. Here are a couple of examples of text from Culpeper’s Herbal.

Descrip. — This tree seldom groweth to any great bigness, but for the most part abideth like a hedge-bush, or a tree spreading its branches, the woods of the body being white, and a dark red cole or heart; the outward bark is of a blackish colour, with many whitish spots therein; but the inner bark next the wood is yellow, which being chewed, will turn the spittle near into a saffron colour. The leaves are somewhat like those of an ordinary alder-tree, or the female comet, or Dog-berry tree, called in Sussex dog-wood, but blacker, and not so long: the flowers are white, coming forth with the leaves at the joints, which turn into small round berries first green, afterwards red, but blackish when they are thoroughly ripe, divided as it were into two parts, wherein is contained two small round and flat seeds. The root runneth not deep into the ground, but spreads rather under the upper crust of the earth.

Descrip. — It being a garden flower, and well known to every one that keeps it,

I might forbear the description; yet, notwithstanding, because some desire it,

I shall give it. It runneth up with a stalk a cubit high, streaked, and somewhat

reddish towards the root, but very smooth, divided towards the top with small branches,

among which stand long broad leaves of a reddish green colour, slippery; the flowers

are not properly flowers, but tufts, very beautiful to behold, but of no smell, of

reddish colour ; it you bruise them, they yield juice of the same colour; being

gathered, they keep their beauty a long time: the seed is of a shining black colour.

From: http://archive.org/stream/culpeperscomplet00culpuoft/culpeperscomplet00culpuoft_djvu.txt

In both these sections, you see the same words occurring repeatedly: flower, divided, root, seeds. That’s just what you’d expect to see in a herbal, which by definition deals with plants and their parts, but you don’t see this pattern in the Voynich Manuscript pages with illustrations of plants. If the text in the manuscript really did relate to what was in the illustrations, you’d expect to see some words occurring frequently in the pages with illustrations of plants, but not as frequently in the pages with illustrations of zodiacs. You’d then expect to start spotting regularities within each page, like the way that the Culpeper descriptions mention size first and seeds last. But you don’t see any patterns like that in the Voynich Manuscript text. It’s yet another odd, major absence.

The 1912 summary

By this point, the 1912 linguist would have decided that the poem above is probably in Finnish or a related language. They’d be right; it’s a short extract from the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala.

They’d also have decided that Voynichese is very, very different from any known real language. They’d be right about that, even without the statistical evidence that shows other ways in which Voynichese is very different. Those differences aren’t just accidental differences that could be explained away as the result of Voynichese being a language from a very different language family. The short common words in particular are short for a reason; they get used a lot, and they get worn down like pebbles in a stream. You see the same effect of short common words across completely unrelated language families; it’s a product of cognitive economy, not of linguistic descent. For a real language not to show patterns like this would be extremely odd. Whatever we’re seeing in the Voynich Manuscript, it certainly doesn’t look like a language, and it doesn’t look like a language ought to look.

The 1580s summary

There wouldn’t be a linguist available to assess the text above or the Voynich Manuscript in the 1580s, since at that time linguistics as a discipline was far in the future. There would, though, be plenty of people who spoke more than one language, since intellectuals at the time would routinely learn Latin, and there would be a fair number of intellectuals who spoke a non-Indo-European language, either Hebrew or Arabic.

However, the tests they could apply to either the poem fragment above or to Voynichese would be very limited. They would be able to spot that the poem fragment was a poem, and in a language that probably used suffixes in much the same grammatical way that Latin does; they would spot that Voynichese was very different from any language that they knew. They wouldn’t know, however, just how odd Voynichese is.

Another potentially significant piece of context was that in the 1580s, the New World had been discovered, and the great voyages of exploration were taking place. The explorers were discovering civilisations and languages very different from anything previously suspected by Europeans. Against that backdrop, a book in an exotic language would be something that an educated would-be buyer would be mentally prepared for. Interestingly, though, the illustrations in the Voynich Manuscript are very un-exotic; there are no scenes of fabulous cities or flamboyantly-clothed kings and queens, no hint of influence from sources such as the Aztec books encountered by Spanish explorers and conquerors. The image below is from one of the handful of those books that escaped destruction by the Church; it’s known as the Dresden Codex, after the city where it is now kept.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dresden_codex,_page_2.jpg

The Voynich Manuscript, instead, has just odd plants, and strange scenes of naked women in weird baths, and slightly unusual zodiacal diagrams. Strange, yes, but looking overall like a European mediaeval book, not like a journal of some amazing journey to far-away exotic lands, or a book brought back from one of those lands.

The 1400s summary

The summary for the 1400s is similar to the one for the 1580s, except that the New World wasn’t discovered till 1492, very near the end of the century. That doesn’t mean, though, that the European scholarly world was insular and benighted. There had been long-distance trade for centuries; for instance, when William of Rubruck visited the Mongol Khan in 1253, he found that there were already several other European visitors there, as a quite routine feature of Mongol court life. Overall, though, the level of linguistic scrutiny at this time would be far lower than in 1912.

Conclusion

So, if you were a would-be hoaxer, and you were thinking of producing something that looked like a book in an unknown language, what sort of examination would you expect it to face at three key points in history?

The short answer is that the scrutiny in 1912 would be much better informed and much more searching than the scrutiny would be in either the 1580s or the 1400s. In consequence, producing a plausible hoax of an unknown language would be a lot more difficult and potentially expensive in 1912. That wouldn’t necessarily be a show-stopper. For someone hoaxing just to make money, the key question is the likely return on investment, not the initial cost of that investment. However, the harder scrutiny would increase the chance of the book failing to pass scrutiny by the would-be buyer’s assessors.

I think, therefore, that it’s plausible that a hoaxer in the 1400s or 1580s might try to make the Voynich Manuscript look like an unidentified language. I don’t think that a hoaxer around 1912 would try to do that, if they had any sense. Around 1912, it would be a much safer bet to make it look like an uncracked code.

Interestingly, Voynich almost immediately started working on the assumption that the Voynich Manuscript was a coded text by Roger Bacon, rather than an unidentified language. There’s just too much that’s strange about the text of the Voynich Manuscript for serious linguists to believe that it could be an unidentified language. The Voynich Manuscript could have masqueraded as an unknown language pretty easily in the 1400s or 1500s, but in Voynich’s time, the “unknown language” explanation was shot down almost immediately. That left the hoax explanation and the code explanation as the two main contenders, and at the time, nobody could see a way of hoaxing the strange regularities that occur throughout the manuscript, so the code explanation emerged as the leader by default.

In the next episodes, we’ll see some of the problems with hoaxing something that looks like an unknown code, and we’ll see how strange regularities can arise as unintended side-effects of a simple hoaxing mechanism.

Notes

Translation of the Kalevala fragment used in this article:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalevala

Background context: I’m posting this series of articles as a way of bringing together the various pieces of information about the hoax hypothesis, which are currently scattered across several sites.

Quick reassurance for readers with ethical qualms, about whether this will be a tutorial for fraudsters: I’ll only be talking about ways to tackle authenticity tests that were available before 1912, when the Voynich Manuscript appeared. Modern tests are much more difficult to beat, and I won’t be saying anything about them.

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers