Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 23

October 10, 2013

Yoda in tech support

By Gordon Rugg

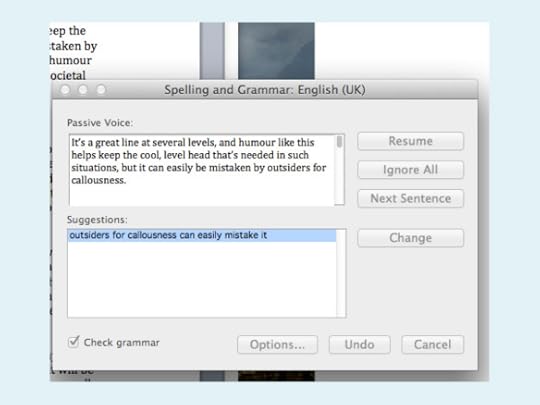

Ever wondered why Yoda speaks backwards?

It was because he once worked for Microsoft on the spelling and grammar checker development team…

Here’s what happened when I was spell-checking an earlier article for this blog.

October 5, 2013

Gordon’s Art Exhibition: Visualisations, women and epics

By Gordon Rugg

I have an art exhibition opening next week in Keele University, which will feature some of the topics that we’ve blogged on here.

The official opening is on the evening of Wednesday 9th October, starting at 6.00, with a talk about the exhibition starting around 6.30. Refreshments will be provided. The exhibition will run from Monday 9th October to Friday 25 October.

Entry is free.

There’s more information about the event here:

http://www.keele.ac.uk/artskeele/visualart/title,97521,en.php

If you’re planning to come, it would be helpful if you could click on the booking link to say that you’re coming, so we can get the catering numbers right, but it isn’t essential. The exhibition will be in the central part of the Chancellor’s Building at Keele University, near the Student Union Car Park. Keele is near Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stoke-on-Trent, a couple of miles from Junction 15 or 16 on the M6 motorway (depending on whether you’re coming from the north or south).

The exhibition will look at depictions of gender in texts across time, using Search Visualizer and visualisations of category theory to examine some of the issues involved.

I’ll write an update on how it goes.

We’ve blogged about using Search Visualizer to look at gender in Shakespeare, here:

http://searchvisualizer.wordpress.com/2012/07/13/gendered-language-in-shakespeare/

We’ve also looked at ways of representing different types of categorisation visually, here:

The exhibition and lecture will bring these themes together, and will look at some other related themes, including biases in human aesthetics.

These themes are also explored in my book Blind Spot:

http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Spot-Solution-Right-Front/dp/0062097903

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

September 24, 2013

Client requirements: Why clients change their minds, and what you can do about it

By Gordon Rugg

This article is one in a series about the problem of identifying and clarifying client requirements. This episode looks at why clients often appear to change their minds dramatically, and how you can handle that problem within your development process.

Readers who like the extended metaphor of the client requiring an image of an elephant might like to know that we’re continuing with it in this article. Readers for whom the novelty of that metaphor has worn thin might like to know that we won’t be using it much.

So, why do clients appear to change their minds radically? It’s often because of a very simple reason that is easy to handle.

Often a client will be clear, firm and decisive about one of their requirements, even if the other requirements are fuzzy and/or negotiable. It’s tempting to assume that the clear, firm requirement is the one you should treat as a fixed starting point. However, that isn’t necessarily the case. Sometimes, in fact, it’s the worst place to start, since those firm, clear requirements are often a real pain, like the client who insists on using an elephant as the product logo, or who wants the building to have a thatched roof which is going to be a nightmare to instal, or the client who wants the software to include a feature that will cause a lot of upgrade problems.

I often have to deal with a very similar issue when I’m helping students to choose the topic for their final year or MSc project. I have strong feelings about this, since a little support at this point can help students to achieve far more on their projects than they ever thought possible. I’ve known undergraduates who liaised with leading figures from forensics and Hollywood as part of their projects, for instance.

The usual script I use for the conversation is to ask the student what their dream outcome would be, and then to craft a project topic that’s a stepping stone toward it. One thing I learned long ago is that the conversation shouldn’t take that dream outcome as the final goal. Here’s why.

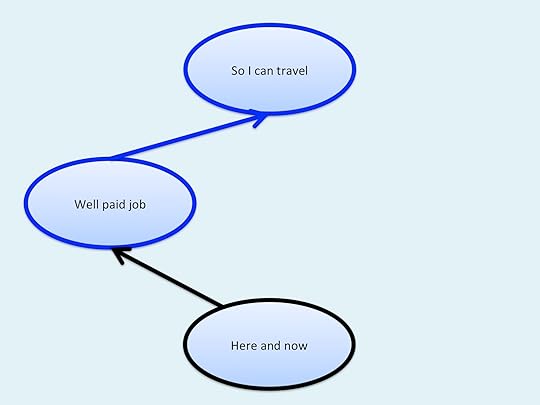

A common answer about the dream outcome is getting a well paid job. It might look as that is the end point, but you often get very interesting replies if you ask why they would like a well paid job. Here’s one common answer.

A lot of students want a well paid job so that they will have enough money to travel. The “dream outcome” is actually just a sub-goal, on the way to the real dream outcome, which is to travel.

Once you know what the real dream outcome is, then you can start to think about other ways of getting there. Here’s a classic alternative route, in green.

If you get the right sort of job in the travel industry, you can be paid to travel. When the student looks at this option, they often swiftly decide that this makes a lot more sense than doing a boring well paid job and then spending their own money for a limited amount of travel a few days per year. So, you end up with this situation.

It looks as if the student’s requirements have changed dramatically. In fact, the top level goal has remained unchanged; it simply hadn’t been mentioned in the initial conversation. All that’s changed is the route to that goal.

It was a similar story when we developed the Search Visualizer software. The top level goal was helping people find relevant documents. Most other people were trying to do this using words, by showing text from each document. We realised that a much more efficient solution was to show where the user’s keywords occurred. This was a completely different route to the same top-level goal. It also had some useful bonus side-effects, like letting users identify documents in other languages that were worth getting translated, or helping users to find relevant sections in very long texts.

The approach we use to find out higher level goals is technically known as upward laddering. In practice, it looks to the client like a simple question about what they’d love to have as a dream outcome.

Often, you can also do downward laddering from that dream outcome, by asking the client whether they can suggest any other ways of getting to that outcome. This usually makes the client happy, and might produce some sensible ideas. If the client can’t come up with other suggestions, then you can use idea generation techniques such as Idea Writing or constraint relaxation to come up with some possible routes that would be more suitable than the client’s original one.

In the next article, we’ll look in more depth at ways of achieving goals, and at ways of establishing whether those goals have been met.

Notes

As usual, I’ve used bold italic for technical terms where it’s easy to find further reading. I’ve listed some specialist links below.

Our previous article about Idea Writing is here:

There’s a tutorial article about laddering on the main Hyde & Rugg site here:

http://www.hydeandrugg.com/resources/laddering.pdf

The Search Visualizer site is here:

http://www.searchvisualizer.com/

The Search Visualizer blog is here:

http://searchvisualizer.wordpress.com/

September 21, 2013

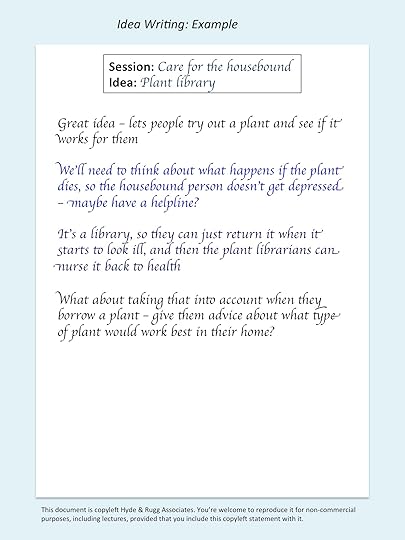

Idea Writing: Generating practical ideas quickly and efficiently

By Gordon Rugg

Generating ideas in groups is difficult. Dominant personalities can take over, or arguments can start between factions. Even for the most constructive and positive groups, most group-based methods involve only one person speaking or writing at a time, while the others sit and wait their turn.

This article is about Idea Writing. It’s a simple, efficient way of generating and developing ideas. The core concept is that each idea gets its own sheet of paper and that everyone writes their comments about the idea on each sheet. They also comment on what other people have written.

Working in this way means that everyone is active simultaneously, without having to wait their turn. It also avoids problems with arguments and dominant personalities. It has the further advantage that you don’t need someone acting as scribe for the session.

It’s a useful method to have in your kit. This article gives an overview with a worked example.

September 19, 2013

Client requirements: Finding boundaries, constraints, and the shape of the elephant

By Gordon Rugg

This article is one in a series about the problem of identifying and clarifying client requirements, using the ongoing semi-humorous example of a client’s requirement for an image of an elephant. This episode looks at ways of establishing the key issues in the client’s requirements when you’re trying to trade off costs against risks.

Finding and clarifying the client’s requirements takes time and costs money, which could be spent instead on development. However, if you make a mistake in the requirements, then correcting that mistake will cost you time and money – often more time and money than it would have cost to get the requirements right in the first place. Often, but not always. So you end up having to balance the certainty of requirements costs against the risk of greater costs further on if you get it wrong. How can you improve the odds in your favour?

One important question involves whether you’re developing a completely novel product, or just a version of an already-established product.

With completely novel products, the client by definition won’t have seen anything similar before, so the requirements process is very much about discovery and exploration and negotiation, with a lot of uncertainty, and often with rapid extreme changes in requirements, particularly in the early stages. One key challenge is identifying the boundaries for the product, particularly as regards requirements involving legal issues or health and safety issues.

With versions of already-established products, on the other hand, the client and you will both have a clear idea of the issues and options and boundaries, and the requirements process is more about choosing what the client wants from within a well-understood set of possibilities.

However, even when you’re developing what looks like a new version of a well established product, you often encounter unwelcome surprises. A clear idea isn’t always the same as a correct idea. I’ll illustrate this using a scenario where the client tells you that they want a picture of a side view of an elephant. That sounds comfortingly familiar, so you ask how big elephant should look in the picture, and the client sketches in the air and says “About this high”.

What could possibly go wrong?

The thirteenth month of the year

So, you produce a picture like the one below, and show it to the client. I’ve left in the “about this high” bar to show that it fits that requirement.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephant_side-view_Kruger.jpg

And the client tells you that this is completely wrong, because the elephant needs to be facing the other way, because of a key requirement that they completely forgot to mention.

If you’re just producing a picture for the client, this news is irritating, but not a huge problem. If, on the other hand, you’re an architect designing a building for the client, this news could be a major problem.

Clients often forget to mention key requirements because those requirements are so familiar to them that they assume the requirements are equally familiar to everyone else. There are plenty of examples of requirements and constraints that make sense once you know the full story, but that you’d have little chance of predicting in advance. One example is organisations that run on a 13 month year, rather than a 12 month year. That’s surprisingly common; I once had two students in a group of thirty who had each worked in different companies that used a 13 month year.

If you’re producing novel software, then you’re on the lookout for these unexpected requirements from the outset. If you’re producing a new version of a familiar type of software, you’re more likely to be caught off guard.

One quick way of getting an overview of the requirements is to do some quick mockups and show them to the client. The mockups don’t always need to be sophisticated. I use whiteboards a lot for quick mockups. My office at Keele has a whiteboard with a basket of whiteboard pens beneath it, so that everyone in a meeting can sketch what they mean on the board. It’s also possible to do quick and dirty mockups on PowerPoint, especially if you’re designing software. You can mock up a series of screens as separate slides, and then show them as a slideshow to simulate moving through the software. A great advantage of visual mockups is that they involve much less risk of misunderstandings than verbal descriptions. With verbal descriptions, you often end up with each party having a clear, sensible and completely incorrect belief about what the other party has just said.

Rapid mockups help, but they won’t catch everything. They probably won’t catch rare events, or legal constraints, for example. For those, you need to find the boundary requirements – the edges of the elephant.

Here’s an illustration of what that might look like with the elephant example. You’ve flipped the image round, and done some in-depth probing about the initial requirement for height, and you’ve found where the client wants the back of the elephant to be, and that’s all fairly close to your expectations. I’ve used a light green overlay to show the requirements that you’ve confirmed, superimposed over what you’re expecting the rest of the image to look like, give or take a bit. It’s a fairly close fit so far.

Pushing the elephant analogy a little, you can establish one set of boundaries for the requirements by looking backwards, at cases in the past, which have become precedents for what’s required today. In many fields, there were landmark legal cases in the past which established legal requirements that have been in force ever since.

You can get at these backward-looking requirements using various methods, such as critical incident technique. This technique was developed by Flanagan in the middle of the last century, and is a well-established way of picking out the lessons to learn from key events in the past. Often, these events are accidents or near-accidents, and often there are official inquiries into them, and often those inquiries produce official reports that then become part of best practice and/or legal requirements. A classic example is the Therac-25 disaster, which was dissected in detail by Nancy Leveson. If the requirements involve sensitive topics, such as bad practice within the client’s organisation, then you might use some of the methods described in the previous article in this series, such as projective techniques.

Looking backward helps with one set of requirements. That’s not the whole story, though; you also need to get at forward-looking requirements, about where the client wants to be, and about possible future problems that the client wants to avoid. Continuing with the elephant analogy, you might interview the client about this, and discover that your image of the requirements now looks like this.

This doesn’t look right. The latest set of requirements looks like a head, but it’s nothing like a fit.

With both forward-looking and backward-looking requirements, there’s a high chance of the client mentally overestimating or underestimating the size of an issue. It’s fairly easy to catch this with backward-looking requirements, if you can get access to data about previous cases. It’s more difficult with forward-looking requirements.

This is a major issue if you’re developing a safety-critical system, where system failure can cause injuries or death. People aren’t very good at predicting what might go wrong, or how likely it is to go wrong. There’s been a fair amount of work into this general area. Here’s an example. If you produce a fault tree for the ways that a system or product can go wrong, and then add a wrong branch to that tree, then people are pretty good at spotting the error (for instance, if you add an error about propeller failure to a fault tree for jet engines). However, if you remove correct branches, instead of adding incorrect ones, then it’s surprising how many branches you can remove before people spot that there are branches missing. People are usually better at spotting active errors of commission rather than negative errors of omission. Human memory is also liable to numerous types of distortion and error; the work of Elizabeth Loftus has shed considerable light on this topic.

There are ways of tackling these problems. You can start by using some cradle to grave scenarios, where you begin at the start of whatever the system does, and work through to the end of whatever the system does, noting any points along the way where the scenario could go off in more than one direction. A classic everyday example is an online shopping system, where the scenario would probably start at the point where the shopper logs onto the site, and end at the point where the shopper logs off.

If you’re building a safety-critical system, then you’ll probably be considering methods such as THERP, which is a technique for human error rate prediction (hence the acronym). There are also numerous methods for predicting and assessing risks; it’s a topic that we’ll return to in later articles.

Humans tend to think about three separate but overlapping concepts when they’re dealing with risk. One is probability – how likely is it that the event will happen? Another is severity – how bad will the outcome be if it happens? The third is dread – how scary is the outcome? All of these make sense, but they have very different implications for estimation and management.

When you’re dealing with requirements, you often have to tease apart issues that such as these, where the client might be conflating issues that are logically separate, or, conversely, might be making a specialist distinction between issues that are clearly separate in the client’s field, but that are usually conflated elsewhere. For instance, some fields make a very clear distinction between elapsed time and time on task; others don’t.

Pushing the elephant analogy one last time, this issue of requirements disambiguation can help make sense of situations like the one in this image.

Here, one image chunk is pretty similar to what you were expecting, apart from the trunk pointing in a different direction, but there’s another image chunk that’s unexpected.

It’s now becoming clear that the image the client has in mind is more complex than the original description. When you dig further into the requirements, you discover that the client was actually thinking of something like this.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephants_at_Hagenbeck.JPG

It’s mainly a picture of an elephant in side view, as originally stated, but there’s a lot more going on in addition. Requirements have a habit of being like that…

The bigger picture

We’ve seen enough elephant images and laboured analogies for one article. What other issues are there that still need to be considered when you’re doing requirements?

One issue is “upwards” requirements: Why does the client want this particular set of requirements, and what are the implications for how changeable those requirements might be, and for the choice of design solution?

Another issue is “downwards” requirements: How can you unpack the client’s requirements and turn them into specific, objective statements that let you properly assess the implications for design and production?

A third issue is measurement: What do you and the client need to measure to make complete sense of the requirements, and how do you set about measuring those things?

These will be the topics of the next three posts in this series. That should take us to the end of the elephant theme. In case you’re wondering, there’s a reason that I’ve used the theme of elephants, rather than examples from, say, software development. I’m trying to show the similarities in underlying issues across a wide range of design and development fields, and I’ve found in the past that if you use worked examples from one field, then people from the other fields tend to switch off mentally because they think those examples are unrelated to their field. Using completely different examples such as the elephant theme reduces this problem, but it can also lead to readers wondering what elephants have to do with anything. There’s probably a better way of handling this issue, but if so, I haven’t found it yet; constructive suggestions would be welcome.

I’ll be posting again about design and requirements in later articles; however, I’ll probably feel less tempted to try using an extended analogy in them…

Notes

As usual, I’ve used bold italic for technical terms where it’s easy to find further reading. I’ve listed some specialist links below.

The Therac-25 case is described on Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therac-25

There’s a copy of the Leveson paper here:

http://sunnyday.mit.edu/papers/therac.pdf

THERP is described on Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technique_for_Human_Error_Rate_Prediction

September 13, 2013

Requirements that clients don’t talk about: The elephant in the room

By Gordon Rugg

He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision,–he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath–

“‘The horror! The horror!’

This article is one in a series about the problem of identifying and clarifying client requirements, using the ongoing semi-humorous example of a client’s requirement for an image of an elephant. The previous episodes have looked at some bad ways of tackling the problem. This episode looks at methods for tackling difficult areas of requirements gathering, where people are for various reasons reluctant to talk about a particular topic. It also looks at the underlying reasons for that reluctance.

That takes us into some uncomfortable and morally ambiguous territory, which is why I’ve opened with a quote from Heart of Darkness. If you’re trying to fix real problems, then you need to know how to find out the realities, and that isn’t always fun.

Some parts of reality you’ll know about via personal experience. Other parts, though, are trickier. How do you find out what people actually do behind closed doors, or when they think nobody is watching? Here are some methods.

Shadowing is simple and effective. It is what it sounds like; you get someone’s permission to follow them round for a while, and you see what happens when you follow them. That can give some surprising insights. One of my students shadowed some IT managers. She also interviewed them, and used a couple of other methods to find out about what they did. It was only when she shadowed them that she discovered that they often worked straight through the day without a lunch break. For them, that was something so familiar that they hadn’t thought of mentioning it.

Shadowing can be particularly useful for spotting apparently minor points that are much more significant than they look. For example, if you shadow a parent who has a child in a pushchair, you’ll quite likely find that they use the disabled toilets, because those have much easier access and more space. They also avoid problems that would otherwise be awkward, such as what a father does if he has a small daughter with him who needs to go to the toilet – he can’t go into the women’s toilet, but taking her into the men’s toilets wouldn’t be a great option either. There are other groups who also routinely use the disabled toilets because of the extra space, such as older shoppers with wheeled shopping baskets. In fact, with regard to toilet provision, there are now effectively three genders, namely male, female and people needing extra space.

Once you start thinking that way, then you can start thinking about ways of adding other design features to help those categories of users. For instance, should you include more coat hooks than usual in disabled toilets, to accommodate children’s coats and parents’ coats?

Shadowing is also effective for spotting hassle points, where a feature is causing irritating problems that are individually minor, but that are affecting large numbers of people every day. Pushchairs and wheeled shopping baskets are again classic examples, as regards awkward provision of steps and stairs, or cramped access points. A little effort redesigning those points can make a big overall difference to the usability of a public space, and reduce the number of accidents and consequent lawsuits.

If you’re planning to use shadowing, it’s a good idea to do a couple of pilot sessions first, and to try analysing the data from those pilot sessions before you start your main work. That will identify the key low-level issues that you’ll need to get right – for instance, what the best method for recording your observations is, and how to measure what you’re observing. A useful tip is to treat swearwords as your best friend; whenever the person you’re shadowing swears, or causes someone else to swear, then you’ve found a problem that needs to be treated as a high priority. Another useful indicator is if the person you’re shadowing suddenly stops talking – to you, or the child in their pushchair – because they’re having to concentrate on something that they find risky or difficult.

Projective approaches can also be very effective. When I was working with some colleagues on the problem of why mature students dropped out of higher education courses, we knew why the students said that they dropped out. Far and away the most frequent stated reason was money problems. That was what they were saying, and that was what surveys across the country were reporting, but we suspected that it wasn’t the full story. So we used a projective questionnaire.

The first half of the questionnaire asked the respondents to list the five main reasons that they thought most mature students would give for dropping out of a course. The second part asked the respondents a very similar question, but with one key twist. It asked the respondents to list the five main reasons for mature students actually dropping out of courses that those students would be unwilling to mention. The questionnaire was projective because the respondents were answering as if they were someone else, not themselves. As we expected, that made a big difference to the results we obtained.

The results from the first half of the questionnaire were in close agreement with the results from previous surveys. That was a useful calibration result for our findings.

The results from the projective second half were very different, and included all sorts of things that people hadn’t been mentioning in the previous surveys, such as sex, drink, drugs and jealous partners.

Our questionnaire also asked the respondents to rate how serious they thought each of the issues really was. The ratings suggested that the “not talked about” reasons were not significantly more serious than the reasons that people were willing to talk about.

That doesn’t prove that those previously-unmentioned issues really were the causes of students dropping out. With projective techniques, there’s always a risk of tapping into urban legends. However, the results gave us some very interesting pointers about topics for follow-up research using other techniques such as indirect observation.

Indirect observation

In brief, indirect observation involves making inferences from things that you can observe about things that you can’t observe directly. Here’s an example that brings together several key points, continuing the elephant theme. It’s a picture of a baboon picking out undigested seeds from elephant dung and eating them. Reality isn’t always pleasant, but if you want to improve a situation, then you need to understand the reality.

So what can you infer from this image via indirect observation? For a start, you can tell that an elephant has been here. You can actually tell a lot more from the elephant dung, if you know what to look for; you can tell what the elephant has been feeding on, and when it dropped the dung. You can tell other things as well, with much deeper significance. Why is the baboon foraging for seeds in elephant dung rather than gathering seeds directly off plants? Combined with the dry, bare ground, that behaviour suggests that this photo was taken in a hard season, with little food available.

That’s what you get if you look beyond any initial squeamishness you might feel. Once you get into the habit of looking for indirect evidence, and looking past any initial squeamishness, you soon start spotting sense in things that had previously looked random or unimportant. Often, getting past the squeamishness is a key point, since it lets you see the underlying patterns in reality much more clearly and completely.

Consultants who deal with organisations can tell a lot from indirect observation. Usually, they’ll have a pretty good idea of the state an organisation’s in before they even reach the client’s office door, as a result of knowing what tell-tale signs to look for.

The next sections look at underlying causes for people being reluctant to tell you the reality; there are several main reasons, each with different implications.

Unofficial working practices

The German sociologist Max Weber lived at a time when Prussian bureaucracy was in full flower, and he made full use of that opportunity to study organisational behaviour at its most elaborate.

One of the many interesting patterns he described involved the importance of unofficial working practices. These are practices that bend, break or ignore the official procedures, often for the simple reason that the official procedures just don’t work in the real world.

Here’s an example. Back in the old days, if you were on a building site and you uncovered a section of metal pipe, the official working practice was to call all the relevant organisations – the gas board, the electricity board, and the water board – and asked them if it was one of their pipes, and if so, whether it was live. What quite often happened was that they all denied responsibility for it, which left you with a problem. The unofficial working practice was then to give some luckless individual a hacksaw and a box of matches. If water came out, then the unofficial procedure was to grab the pipe tightly to keep the leakage to a minimum, and call the water board again. If no water came out and cables were visible, then the unofficial procedure was to stop sawing immediately, and call the electricity board again. If gas came out, the unofficial procedure was to strike a match immediately and light the gas; as long as you were fast, you were okay, because you’d just get a long jet of flame while you waited for the gas board to arrive, rather than an explosion.

That’s perhaps an extreme example. Every organisation has huge numbers of unofficial practices that are easier on the nerves than that one, but that people will still be reluctant to admit to. Many of those procedures are unofficial simply because the official ones are poorly designed. A classic case is when people are forced into unofficial practices so they can work around limitations in the computerised record system, where some software designer has either not known or not cared about how the system should be structured to meet the realities of the client’s needs.

Espoused theories versus theories in use

People usually know when they’re using unofficial working practices; they may not like being put into the position of having to use those practices, but they are aware that they’re using them.

Sometimes, though, people aren’t fully aware of what they’re really doing. There’s a useful distinction, introduced by Argyris, between how an organisation thinks that it behaves (the espoused theory) and how it actually behaves (the theory in use).

A classic example was a timber company where the management genuinely believed that it had a tough, no-nonsense, macho management style. In fact, when researchers studied it via shadowing, the management style involved a lot of informal bonding between management and staff, in contexts like barbecues and drinking together. The reality was that the management were paying a lot more attention to social bonds and communication than the management of most city offices.

Front and back versions

Unofficial practices usually involve people deliberately doing things that they’re not supposed to do; espoused theories often involve people doing things without realising that they do them. There’s another major reason for people not telling you about what actually happens; this one often involves professional pride.

The sociologist Erving Goffman used the analogy of theatre performances to illustrate an important regularity in everyday life. With theatre, there’s the performance that’s shown to the audience, and there’s the very different reality that happens backstage at each performance, with costume changes and scene changes and the fixing of numerous minor last-minute crises.

Goffman pointed out that we see the same in everyday life. For example, doctors and airline pilots present a professional persona to the public – calm, in control, knowing just what they’re doing – regardless of whether they’re actually panicked and without a clue about what to do next.

Goffman called the professional persona the front version, and the behind-the-scenes reality the back version. It’s a very useful distinction.

One interesting thing about back versions is that they’re often very different from what you might expect. A good example is the sociologist who was shadowing a couple of American cops who took a call from a woman who claimed her dog had been abducted by aliens from space. When the cops had finished taking her statement and returned to their car, the sociologist was surprised to see that they then completed all the paperwork as if it was a perfectly normal case. He’d been expecting them to use an unofficial working practice of just ignoring it.

Their decision rationale made complete sense of why the back version here was the same as the front version of how to handle the case. They explained that if they didn’t log the case in the official paperwork and the woman called the station later to ask how the case was going, then they would end up being dragged through procedural audits, which would be unpleasant and very time-consuming. From their point of view, it was much quicker and easier simply to log it like any other case, and then leave it to be someone else’s problem.

As an outsider, you’ll usually be given the front version when you meet people, whether as a designer or a researcher or a consultant or in some other capacity. If you’re aware of this, and aware of how it differs from espoused theories and from unofficial working practices, then you’re at least part-way towards finding out the information that you actually need to know.

Closing thoughts

The previous sections have contained a lot of discussion about unpleasant realities that we have to understand properly if we want to produce something better. It’s often ambivalent territory.

This article opened with a well-known quote from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. I’ll close with the less famous ending of the book, which illustrates brilliantly just why people might face deep moral ambivalence about whether to tell the truth or to conceal it. The context is that Marlow, the narrator, has returned from his journey to find Kurtz, and is meeting Kurtz’s fiancée. She is utterly unaware of the horrors that Kurtz saw and the horrors that Kurtz perpetrated. Marlow is torn between the truth, and sparing her needless grief.

“I pulled myself together and spoke slowly.

“‘The last word he pronounced was–your name.’

“I heard a light sigh, and then my heart stood still, stopped dead short by an exulting and terrible cry, by the cry of inconceivable triumph and of unspeakable pain. ‘I knew it–I was sure!’ . . . She knew. She was sure. I heard her weeping; she had hidden her face in her hands. It seemed to me that the house would collapse before I could escape, that the heavens would fall upon my head. But nothing happened. The heavens do not fall for such a trifle. Would they have fallen, I wonder, if I had rendered Kurtz that justice which was his due? Hadn’t he said he wanted only justice? But I couldn’t. I could not tell her. It would have been too dark–too dark altogether. . . .”

Marlow ceased, and sat apart, indistinct and silent, in the pose of a meditating Buddha. Nobody moved for a time. “We have lost the first of the ebb,” said the Director, suddenly. I raised my head. The offing was barred by a black bank of clouds, and the tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth flowed somber under an overcast sky–seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness.

Conrad, “Heart of Darkness”

Notes

The baboon image is from here:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baboon_eating_elephant_dung.jpg

September 9, 2013

The Voynich Manuscript and the Unexplained Files

By Gordon Rugg

I’ve just watched the feature about the Voynich Manuscript on “The Unexplained Files”.

Sigh.

If you’ve just encountered the Voynich Manuscript for the first time via that feature, here’s a quick overview of how most Voynich researchers actuallly view the evidence.

Between 1912 and around 2004 the general consensus was that the text of the manuscript was too bizarre to be a language, and too complex to be a hoax, leaving a code as the only remaining plausible explanation. However, ninety years of work by the world’s best cryptographers found no sign of a code.

I showed that in fact it was possible to produce a meaningless hoax as complex as the text in the manuscript, and showing many of the same statistical properties as accidental side-effects, using very simple technology – basically a card with three holes cut in it, and a big table of gibberish syllables. This made a hoax a simple, feasible explanation; there was no need to look for a super-code so sophisticated that the world’s greatest codebreakers had failed to find it, let alone crack it. Many Voynich researchers still think that there’s a code in there somewhere, and are continuing to look for it. I think that a code is by no means impossible, but not very likely; I think that a hoax is a simpler and more probable explanation.

The documentary mentioned the carbon dates, but those are not terribly helpful; it’s perfectly feasible that a hoaxer would use already-old vellum to make a hoax look more plausible, and old vellum was available in antiquity. (It’s also logically possible that the manuscript contains older text re-copied onto vellum made around 1420, but I don’t think anyone seriously believes that.)

The story has also been complicated by a recent paper by Montemurro & Zanette, which contains numerous unfortunate and serious errors and misunderstandings, which I’ve discussed at length in other articles on this site. I’ve included links to reviews by professionals in other relevant fields, who have been scathing.

So, the documentary didn’t exactly give a clear insight into current research, but its suggestion of an alien code was … interesting…. and it featured some nice photography.

Sigh.

Client requirements: The shape of the elephant, part 4

By Gordon Rugg

This article is about the problem of identifying and clarifying client requirements. It uses the humorous example of a client’s requirement for an image of an elephant, and follows on from the two previous posts about ways of getting the requirement wrong.

The next article in this series will be about ways of getting the requirements right, but for the time being, we’ll continue with examples of wrongness above and beyond the call of duty, starting with a forgotten icon from history, in the form of cartoon character Horton the Elephant.

Bad solution 7: Cartoons always amuse people.

Client’s response: Wrong.

The limitations of this solution are similar to those of the “witty dialogue with the environment” solution and of the “here’s some clip-art” solution; I won’t dwell on those.

What’s more interesting to me is why cartoons are so popular. They’re a simplified, exaggerated model of reality, and the core of how they work is fairly simple. There’s caricature-drawing software that does a good job of producing caricatures from photos by comparing the photo to a schema of a typical face, and then exaggerating the differences between the photo and the typical face. Cartoons draw on similarly simple underlying processes, such as exaggeratedly child-like proportions.

Although people like the familiar and the average, they tend to like the non-average more, in a fairly predictable way. Typically, people prefer faces, features and items that are between one and two standard deviations from the average in statistical terms – for instance, tall people tend to be viewed as more attractive, provided that they’re not too tall (as defined by that statistical percentage). This applies to preferences for a broad range of consumer products, and it can lead to a gradual creep in the norm until some inherent limit is hit (for instance, phone keys getting smaller until they hit the limit set by finger size). This is a separate mechanism from simple competitiveness, but it can easily combine with competitiveness as a further motivating force for fashion wars.

Bad solution 8: I’m an artist; I know better than you; here’s what you should have.

Client’s response: I’m a client; here’s what you should have, if we were in Texas.

There’s a well-worn trope about designers viewing a commission as an excuse to create the work of art that’s been on their personal wish-list for years, and another about architects viewing the building that they’re designing as just an enormous sculpture, with humans involved only as an awestruck audience or as indicators of scale.

A problem with the “design as pure art” view is that it tends to ignore design rationale. Clients often have important reasons for wanting a particular feature in a design; ironically, the most important ones are also usually among the easiest ones to miss, because of Taken For Granted Knowledge. This concept comes from Grice’s work on communication. He pointed out that we don’t say anything that we can reasonably assume our audience to know already – for instance, we don’t bother to mention that our aunt is a woman, because we can reasonably assume that the audience will know that aunts are women. However, people who have been working in a particular field for years tend to be surrounded by other people who share the same specialist knowledge as themselves, and so they mis-judge which knowledge they can safely take for granted in a designer, leading to them omitting to mention the most important requirements.

A different complaint that often occurs in relation to artists involves symmetry. Symmetry is very popular in the animal kingdom; even insects prefer symmetry to asymmetry. Unfortunately, artists often rotate images horizontally to increase the symmetry and balance of a composition, without first checking whether this will cause problems for the client. A classic example in archaeology is illustrations of cave paintings, where the orientation of a painting is a potential clue to the handedness of whoever painted it (and therefore important evidence). However, a lot of published illustrations of these paintings have been rotated by book illustrators to face in the opposite direction to the original, for the sake of artistic composition. This tends not to be well received by the clients…

Bad solution 9: I need to bear witness to my beliefs.

Client’s response: So do I, and I sincerely believe you need to be fired.

This topic is the source of much well-informed debate over on Freethought Blogs and numerous politics-related and religion-related sites, so I won’t discuss it here, for much the same reasons that I didn’t try to headbutt the wasp nest that appeared on our garden shed one summer. You are entitled to have beliefs, but the client and the law might have opinions about the right times and places to express them.

Instead, I’ll tactfully change the subject to laddering. This can be invaluable for finding out about clients’ beliefs, though it obviously needs to be done with sensitivity as regards potential ethical issues. When you ladder up from even the most mundane choices, such as whether to drink coffee out of a cup or a mug, you very rapidly get into core values and beliefs. In one study, we found that most respondents preferred the same product, but for two separate sets of reasons. One set related to expressive behaviour (covered in a previous article here) – the respondents preferred the product because it was a fashion statement. The other set related to instrumental behaviour – the product provided the respondents with more functionality. These two sets of values had very different implications in terms of marketing and design. This is particularly useful when the client wants to make some sort of statement in the finished article; laddering can help clarify what the client wants to say, and can also help clarify which design features will be perceived by the client as sending the desired signal.

What next?

The next articles will look in depth at ways of getting better insights into client requirements. Coming soon: Requirements, elephants and toilets…

Notes

There’s a chapter about the mathematics of desire in Blind Spot; there’s also a fair amount about handedness and symmetry.

http://www.amazon.com/Blind-Spot-Solution-Right-Front/dp/0062097903

The elephant images above are from Wikipedia and wikimedia.

September 6, 2013

Client requirements: The shape of the elephant, part 3

By Gordon Rugg

This article is part of a series about identifying and clarifying client requirements. Handling client requirements isn’t always easy. However, that isn’t the same as “impossible” or “not worth trying”. The previous article covered three ways of getting it wrong, and various ways of getting it right; this article follows on from that point.

As a running theme through this series, we’re imagining that you’re dealing with a client who has asked you to produce an image of an elephant. Here’s another inadvisable solution.

Bad solution 4: My design is in a witty dialogue with its environment

Client’s response: Very funny, go get a job at the circus.

There’s a classic Calvin and Hobbes cartoon which shows Calvin being thrown unceremoniously out of the front door. He’s protesting angrily that if a novelty song is funny the first time, it’s funny the sixteenth time as well.

Humour comes from an unexpected juxtaposition of things that are very different. So does horror. A juxtaposition isn’t unexpected if you see it every day, which is what happens with buildings – there’s a whole genre of buildings that are intended to be visual jokes, rather than places that are good to use, or that bring visual pleasure to as many people as possible, and visual displeasure to as few as possible. Arguing that everyone’s tastes are different isn’t a strong position; yes, at one level, they are, but at another level, there’s enough broad agreement about taste to make some consumer products best sellers while others are very much a minority market, and others again rapidly vanish into well-deserved oblivion.

There are numerous methods for evaluating designs, both in terms of functional requirements, non-functional requirements (a misleading name that should never have been allowed to escape into the world) and subjective opinions with regard to the features relevant to the intended users and/or market. These are well established in some disciplines, and scarcely known in others.

In brief, functional requirements are ones where you can point to the place where that requirement is met (e.g. “This fire escape meets the requirement that the building must have a way for people to get out in the event of a fire”). Non-functional requirements are ones where you can’t do that, because the requirement isn’t met in one single place, but rather via two or more parts of the system (for instance, the requirement that an aircraft can be evacuated within a specified time). Ironically, non-functional requirements are often much more important and practical than functional requirements, since a lot of non-functional requirements involve safety management, as in the example of aircraft evacuation.

Subjective opinions can be handled via techniques such as card sorts, laddering and think-aloud technique, which are all good ways of finding out which features are important to people. There are articles about all these techniques on this site and on the Hyde & Rugg website. Evaluation is a topic to which we’ll return repeatedly.

Bad solution 5: Sex sells.

Client’s response: Not to this client.

What’s the implicit subtext of this approach? It’s basically saying that the sex in the image is a better selling point than the quality of the product. That’s not exactly flattering to the client or to the intended market.

Also, at a deeper level, the world’s changing. There’s a fine line between sensuality and insidious sexism, and there are a lot of more people now calling out anyone who crosses that line. Those people include clients and the intended market. It’s better to treat them properly, and to design something that’s good on its own terms, not because it has a sultry elephant draped across it…

Bad solution 6: I found some clip art that’s a pretty close match.

Client’s response: Would any jury convict me?

Yes, some people actually use this approach. Yes, there are probably some situations where it’s appropriate. No, I can’t think of any at the moment.

This approach is a recipe for trouble on two fronts. One is that it shows the client no skill beyond the ability to use a search engine. That doesn’t exactly strengthen a portfolio, or the likelihood of repeat trade with that client. The other is that images in a professional context are often being used to demonstrate important indicators of quality involving apparently minor features that actually send out a strong signal to the intended audience. There’s an entire genre of humour among professionals based on cases where designers haven’t done their homework, and have produced something that’s hilariously wrong to anyone who knows the field.

There’s an easy solution that involves three simple steps. First, ask the client about any key features that need to be included. Second, show a quick and dirty mockup to the client. The client will now notice all sorts of things that they didn’t mention first time round, because of Taken For Granted knowledge (described in previous articles). Third, produce a revised mockup and show that to the client for feedback. You might still need to tweak the design, but usually it’s only a minor tweak, and you’re now ready to move on to the full-scale proper design. This initial check doesn’t take long or cost much, but it can make things go a lot more smoothly downstream.

This approach works best in combination with user centred design and ego-free design. Learning these approaches can be a bit of a challenge if you’re used to the idea of designer as temperamental and egotistical, but if you do learn them, they have a lot going for them; they also make design and development much more productive, high quality and fun.

Notes

The elephant images above are from wikimedia and Wikipedia, and are used here under the creative commons licence.

September 5, 2013

Client requirements: The shape of the elephant, part 2

By Gordon Rugg

Identifying and clarifying client requirements isn’t always easy. However, that isn’t the same as “impossible” or “not worth trying”. The better your understanding of the requirements, the better the outcome is likely to be. This article is about three bad responses to client requirements, and about better ways of tackling the problem.

As a running theme through this series, we’re imagining that you’re dealing with a client who has asked you to produce an image of an elephant. Here’s one bad solution from the past.

Bad solution 1: Sod it, this will do, they don’t know any better.

Client’s response: You’re wrong about that, and you’re fired.

So how does this situation arise, and what can you do about it?

A key concept in this example is the distinction between satisficing and optimising. These are concepts from the work of economist and decision theorist Herb Simon. A satisficing solution is a good-enough solution; an optimising solution is a best-possible solution.

It often makes sense to go for a satisficing solution, because that usually saves you time as well as money. The trouble with an optimising solution is that usually you can’t know when to stop looking for a better solution, because you have no way of knowing what’s still out there that you haven’t found yet.

If you’re going to use a satisficing solution, then you need to be clear about that with the client, and to get the client’s agreement about what they and you will consider to be a good enough solution. That takes you into territory like metrics and measures, which are well-established concepts in some disciplines, and not so well known in others.

We use laddering a lot for identifying and unpacking the relevant measures. There’s a tutorial article about this on the Hyde & Rugg web site. It’s a cheap, simple, clean and powerful method that only requires pen and paper.

http://hydeandrugg.com/resources/laddering.pdf

We also use laddering to unpack why the client wants a particular requirement. This is an important issue, that we’ll return to at the end of this series.

Bad solution 2: Red is the new black

Client’s response: Then go work for Prada. You’re fired.

As with the previous example, sometimes this is actually the correct way to tackle the problem. One key issue is whether you’re dealing with the design of a novel product or a new version of a well-established product.

This is one of those cases where English doesn’t have exactly the word that’s needed. A novel product is one that “breaks the mould”. Another way of phrasing this is to say that it is based on a new schema. A schema is a mental template for something; for instance, the first Graphical User Interface was a new schema, very different from the previous interfaces based on the old schema of command lines.

If you’re designing a truly novel product, then you’ll usually want to be very different from current fashions and conventions, so you don’t get pigeonholed as being still in the same old schema that you’re trying to replace. Also, the current fashions and conventions might actively get in the way of your new design. We had this issue when designing the Search Visualizer software, where we deliberately made the interface and menu structure very different from those in previous search engines based on the old schema.

http://www.searchvisualizer.com/

If, on the other hand, you’re just designing a product which is a new variation on a well-established theme, then you’ll need to be sensitive to current trends and best practice, so you don’t look outdated.

This is a common cause of problems in design and development. The key skill sets for designing and developing a truly novel product are very different from those required for designing and developing a new variation within a well-established schema. It’s not a case of one approach being inherently better than the other; it’s just that they’re very different. It’s a good idea to check for which of these you’re dealing with as early as possible in the process.

Bad solution 3: Here’s one I found on the Internet.

Client’s response: You can find a new client there while you’re about it.

Again, this is sometimes an appropriate solution. This is particularly relevant in the case of software development, where there’s a lot of good open-source software available that can significantly reduce development costs both in time and in cash.

Often, though, it’s a problem. In the case of open-source software, that software may not do exactly what you want to do, in which case you need to spend time and effort modifying it. Modifying someone else’s code isn’t a lot of fun, and doesn’t always end well. Most programmers at some point in their working lives will have an experience with their own code where they leave a particular chunk of code alone, because it works in its current form, and it breaks if they alter it, for reasons that they’ve never been able to understand.

Another issue involves the signals that you’re sending out to the client. If you’re downloading someone else’s solution from the Internet, what does that say about your own skills, or rather, about your implied lack of skills?

Also, it raises questions about whether you’re aware of potential legal issues involving copyright and fair use. For instance, there are honeypot websites, full of gorgeous innocuous-looking images of things like freshly-baked cakes or beautiful views, that can be used in a wide range of settings. The honeypot site’s owners then use image-search software to trawl the web, finding websites that have downloaded and used the honeypot images without permission, and send a legal letter demanding a huge fee for using the image. The unauthorised users don’t have a legal leg to stand on.

If you decide to go down the route of using material from the Internet, it’s a good idea to talk the client through your decision rationale, to set their mind at rest about this aspect of the project.

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/08/27/decision-rationale-the-why-and-the-wherefore/

Summary

In all three cases above, the problems involve mis-application of principles that can actually be sensible or even best practice in a different context. The solutions in all three cases are cheap and simple, once you know what they are. There are articles on this blog site and on the Hyde & Rugg website that cover these issues. We hope you find them useful.

Notes

The elephant images above are from wikimedia and Wikipedia, and are used here under the creative commons licence.

I’ve followed our usual convention of showing in bold italic useful terms where it’s easy to find further information, and of only including links where it’s difficult to find further information, or where a specific site is involved, to reduce link clutter.

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers