Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 6

September 9, 2016

Teacher Humour: Why spelling matters

By Gordon Rugg

If one of your students ever complains that you’re making too much fuss about correct spelling…

https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/573223858803590270/

(Image used under fair use terms, as a humorous low-resolution copy of an image already widely circulated)

If you want a more detailed explanation, this previous article goes into more depth (but is less artistically striking…)

September 5, 2016

Why Hollywood gets it wrong, part 2

By Gordon Rugg

The first article in this short series looked at one reason for movies presenting a distorted version of reality, namely conflict between conventions.

Today’s article looks at a reason for movies presenting a simplified version of reality. It involves reducing cognitive load for the audience, and it was studied in detail by Grice, in his work on the principles of communication. It can be summed up in one short principle: Say all of, but only, what is relevant and necessary.

At first sight, this appears self-evident. There will be obvious problems if you don’t give the other person all of the information they need, or if you throw in irrelevant and unnecessary information.

In reality, though, it’s not always easy to assess whether you’ve followed this principle correctly. A particularly common pitfall is assuming that the other person already knows something, and in consequence not bothering to mention it. Other pitfalls are subtler, and have far-reaching implications for fields as varied as politics, research methods, and setting exams. I’ll start by examining a classic concept from the detective genre, namely the red herring.

Herring image by Lupo – Self-made, based on Image:Herring2.jpg by User:Uwe kils, which is licensed {{GFDL}}, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2610685

Herring image by Lupo – Self-made, based on Image:Herring2.jpg by User:Uwe kils, which is licensed {{GFDL}}, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2610685

In detective stories, a red herring is a misleading clue that causes the reader and/or characters in the story to think that the plot is going in one direction, when in reality it’s going in a different direction.

The key feature of the red herring is that it’s unconnected to the core plot. Plots normally have twists and turns, but these are usually woven in to the core plot in some way. One common example is the Necker shift, when the audience realises that there’s a completely different way of interpreting the situation. The genre of comedy of errors is based on this type of re-interpretation; conversely, a key moment in many horror movies is when the protagonists realise that the situation is very different from what they had thought. I’ve blogged about this topic before in this article.

Red herrings, in contrast, don’t contribute to the main plot, or show the audience significant new information about a character; instead, they’re like a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that’s designed to be easily misunderstood, adding to the intellectual challenge of the game.

Normal scripts

In normal scripts, every part of the script is intended to be there for a reason. It might be moving the action forward, or it might be giving the audience key information, or it might be showing the audience key features of a character’s personality.

A classic example is the scene in Casablanca where Captain Renault shoots the Nazi Major Strasser, then tells his policemen that Major Strasser has been shot, and instructs them to round up the usual suspects. In a few seconds of screen time, the scriptwriter has shown a major plot event, and given the audience a crucial revelation about where Renault’s sympathies lie, while remaining consistent in its depiction of Renault’s cheerfully corrupt character.

When performed by a skilled scriptwriter, this is an elegant art form that produces memorable one-liners and dialogues. However, this elegance comes at a price.

The price is departure from reality. The real world isn’t an elegant and minimalist environment. Instead, it’s a cluttered, untidy place full of red herrings. That’s one of the reasons that fiction is popular. Fiction tidies up the world, so that we can suspend our disbelief for a while, and enter a world where things make sense, and are consistent with our world view.

That would be fine if there was a clear dividing line between fiction and reality. In practice, though, the situation isn’t that simple.

Fiction makes heavy use of schemata, i.e. mental templates, such as the schema of the comedy of errors, or the schema of the villain being thwarted and punished. Some schemata, however, are much better than others in terms of suitability for fiction.

Here’s an example. A common schema in real world disasters is the normal accident. Many accidents occur because two or more individually minor issues happen to occur together, and interact with each other in a way that leads to disaster. A famous example in aviation is the Gimli Glider, an airliner that ran out of fuel in mid air. This wasn’t caused by catastrophic negligence or by a major malfunction; instead, several small things all went wrong.

This schema is often used in movies to create the lead-in to the main plot. The camera shows the small events that will lead to the major plot challenge, such as the aircraft’s engines failing. From that point on, though, the plot focuses on the immediate challenge, such as getting the aircraft safely to the ground.

Crucially, the plot usually ends once the immediate challenge is over. That’s understandable, from the viewpoint of a film studio wanting to produce a high-suspense movie that will attract large numbers of paying customers. There’s not much likelihood of major box office revenue from a movie about safety researchers in an office systematically producing checklists of best practice so as to reduce the likelihood of disasters happening.

It’s an understandable choice, but it has unfortunate side-effects. When films focus on protagonists wrestling with the immediate problem, they reinforce the stereotype of problems being solved by heroic individual action (usually involving skill in driving, shooting, and unarmed combat).

This can easily reinforce simplistic world views that reduce the world to bad things caused by bad people, and good things caused by good people, with easy and swift fixes for problems.

The world, however, isn’t that simple. Many bad things arise from the way that physical or organisational systems are structured. Often, those bad things are accidental side-effects of the system, or even the opposite of what the system was intended to produce. Fixing such problems is usually complicated, and slow, because of the complexity of the system. This is a major issue in politics, which we’ll examine below.

Implications for education and research

Movies aren’t the only environment affected by the communication principle of saying all of, and only, what is relevant and necessary.

This principle is a significant problem for anyone trying to compose exam questions that involve scenarios or case studies. The candidates will often assume that everything mentioned in the scenario/case study is there for a deeply significant reason. This makes it difficult to include extraneous information in the scenario/case study, which in turn means that students will tend to encounter scenarios and case studies which are unrealistically clean and simple, and therefore poor preparation for the messy complications of reality.

There are similar implications for experimental design if human participants are involved. Participants are likely to look for deeper significance in the wording of the experimental instructions than were intended by the researcher.

This is why it’s a good idea to gather in-depth feedback from pilot studies before firming up the materials for the main study, using methods such as laddering, think-aloud, and projective approaches that are good at eliciting the various types of semi-tacit knowledge that are likely to be involved.

For both these fields, there is also the issue of what isn’t being mentioned, which can be heavily politically charged; we’ll discuss this in more detail below.

Wider implications

The bias towards simple explanations without cluttering detail has implications for history and for politics that are well recognised by professionals familiar with the research in those fields.

Historians, for instance, have long recognised the “great man” model of history, in which key events are brought about by the actions of a few (usually male) individuals. This tends to produce a more exciting view of history than models that focus on technological developments or social movements, but more exciting isn’t necessarily the same as accurate.

This issue is also well recognised in politics, where demagogues can do very well for themselves by claiming that there are simple solutions to complex problems. Those claims often produce memorable one-liners that make effective campaign slogans, but usually those one-liners are memorable precisely because they’re detached from reality.

So, film-makers are pulled in one direction by the need to tell a clean, clear story, and are pulled in the opposite direction by social responsibility. Where does the balance lie? There’s no easy answer. Film-makers sometimes set out to make a deliberate political point. A classic example is High Noon, which was made as a critique of right-wing American political witch hunts.

More often, though, the political stance of a movie comes from the genre and tropes within which it is located. This is well understood in media studies, and is a regular topic in criticisms of the movie, TV and games industries. For instance, the widely-used trope from thrillers that protagonists can extract key information from villains by using torture has come in for considerable critical attention recently, with critics pointing out that the factual, legal and moral problems associated with it.

Similarly, and more subtly, movies can take a political stance via significant absences in what they show. A classic example is the movie of Gone with the Wind. It’s a huge, sweeping, story of a beautiful heroine in love and war. It has some brilliant dialogue, and stunning special effects. And it somehow doesn’t get round to mentioning slavery, or what life would have been like for the slaves on the O’Hara plantation, or how they would have felt about gaining their freedom. Instead, we are shown a tragic portrayal of the heroine having to do her own washing and cooking because she has lost her main source of income as a result of war and emancipation.

In summary, then, there’s no easy answer. However, that doesn’t mean that the media can wash their hands of social or political responsibility for the messages that they are explicitly or implicitly conveying in their story lines and dialogue.

In future articles in this series, we’ll look at other reasons for movies presenting inaccurate versions of reality; we will then suggest some ways forward.

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

July 25, 2016

Will the world end if I don’t get a job soon?

By Gordon Rugg

The short, reassuring answer is no, the world probably won’t end if you don’t get a job soon.

However, if you’re trying to find a job and haven’t found one yet, it can easily feel as if your personal world is closing in around you and about to collapse. This article is about some ways of handling that feeling and of handling the situation so that you get something good and positive out of it.

To set a good, positive mood as a starting point, here’s a picture of a hammock on a tropical beach.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

One key concept is that if you can tell a good, true story in your job applications, you’re halfway there. That’s going to be the main focus of this article. It’s a concept that sounds obvious, until you start to think through just what a good story looks like, as opposed to a bad one or a neutral one or a mixed one. So what makes a good story, and why?

Having a narrative spine is a core feature of a good story. The narrative spine is the plot, or the underlying narrative thread, of the story.

For instance, the plot of your story could be about how you spent a couple of years trying different jobs until you were sure what you wanted to do with your life. That makes sense to potential employers, and it implies that you’re likely to take a positive, committed approach when you get the job that you’re applying for. That’s a good start. The interviewers may have their private suspicions that those three months working on a sloth sanctuary in Central America were just an excuse for an exotic holiday, but they’ll probably not make a big issue of it if the rest of your CV fits reasonably well with that story.

Taking control in this way should also significantly help your morale. It takes some of the time pressure off you, and it gives you a reasonable way of weaving short-term jobs into something more ambitious when you’re ready.

At a practical level, this strategy is also a good way of getting experience, and learning what you love, so that your life and career are something to enjoy, rather than something to endure.

Looking at your applications from the interviewers’ point of view is another core component. This is something that you can weave into your life with little extra effort, but where that little bit of effort can make a huge difference later.

Imagine that an interviewer is trying to choose between four candidates who all have pretty much the same school and degree results. That can happen all too easily with jobs for new graduates. The interviewers need some objective reason for choosing one candidate over the others, if only so that the unsuccessful candidates can’t complain that they were rejected because the interviewers were biased against them.

In this context, any sign of initiative or extra skills can be that key objective reason. Using the sloth sanctuary example, that initiative might involve using your art skills to paint better signage, or your IT skills to improve their website, or your language skills to produce more material for visitors in other languages. If you’re an artist or an IT graduate or a language graduate, those things might only feel like minimal effort on your part, but from the point of view of an interview panel, they’re solid evidence of something useful that you’ve done on your own initiative and that the other candidates haven’t done.

A particularly useful tip about world view when you’re job hunting is to view rejection letters as calibration. You should be aiming to get invited to interview in some, but not all, of your applications. I use 25% as a rough rule of thumb, but you can use a different figure if you prefer. The reason for this tip is that if you’re not being invited to interview in any of your applications, you’re aiming too high; conversely, if you’re being invited to interview in all of your applications, you’re aiming too low.

An added bonus of this approach is that it transforms your perception of the “no interview” letters from a negative emotional response into a practical assessment of whether your pitches are roughly at the right level. That can make a huge difference to your self-esteem, as well as to your job hunting.

A closing practical note

An invaluable resource for any job hunter is the book What Color is Your Parachute?

It’s heavily evidence-based, and contains a huge amount of practical information and guidance. The author is a Christian, but does a good job of keeping his personal faith separate from the evidence. Also, he interprets his faith in terms of following your dreams, and making the most of your talents, which are key features of finding a life path that you truly enjoy.

The book has a supporting website, which is well worth visiting.

On which positive note, I’ll end. There are some links below which you might find useful; I hope that this article has helped you.

Notes and links

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/02/23/life-at-uni-will-the-world-end-if-i-fail-my-exams/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/11/22/life-at-uni-what-do-i-do-with-the-rest-of-my-life/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/18/life-at-uni-after-uni/

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

July 8, 2016

Catastrophic success

By Gordon Rugg

Sometimes, you know a concept, but don’t know a name for it. I’m grateful to Colin Rigby for introducing me to a name for this article’s topic, namely catastrophic success.

It’s a concept that’s been around for a long time, in fields as varied as business planning and the original Conan the Barbarian movie. It’s simple, so this will be a short article, but it’s a very powerful concept, and well worth knowing about.

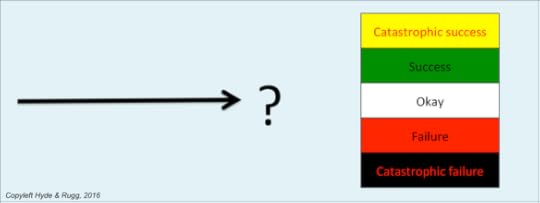

The image above shows a classic project route. The project has been progressing along the line indicated by the arrow, moving towards an “okay” outcome. It has now reached the point where the actual outcome is about to emerge.

Most people have at least an adequate plan for an “okay” outcome in any significant projects that they’re undertaking. People and organisations are often less good at planning for success and failure that fall within normal bounds (i.e. that aren’t game-changing); a common strategy is to play success and failure by ear, because both of them can be hard and/or costly to plan for, since they can take many forms. People and organisations are usually very bad at planning for catastrophic, game-changing outcomes, except in a few fields which have been forced to confront them.

Catastrophic failure has been a key concept in safety-critical fields for centuries; for instance, a bridge collapses while it’s being constructed, or an aircraft engine explodes. A lot of work goes into preventing this type of failure, for good and obvious reasons.

Catastrophic success is not so well known. It involves success on such a scale that it changes the game in a direction that you’re not prepared for. In business, a classic case is a new product being wildly successful, outstripping the company’s ability to keep up with demand, and leading to consumer anger and backlash. Winning the lottery is another well recognised form.

This concept overlaps with the saying Be careful what you wish for; you might get it. The two aren’t identical, though. The saying often involves a moralistic sub-text about greed being punished, and a story line that involves a subtly different parsing of the precise wording in the wish. Catastrophic success doesn’t have that undertone. It can happen to good people and bad people alike.

So, what can you do about it?

One simple strategy is to make sure that you’ve at least thought about how to handle all five of the outcomes listed above. Even a basic, sketchy advance plan is better than no plan, if you’re suddenly hit by catastrophic success and you’re too mentally overloaded to improvise a plan.

What if you plan for catastrophic success and it doesn’t happen? Often, you can re-use that plan within other projects, or as a basis for more ambitious future projects. Also, you may well be able to use it if you’re unexpectedly hit by catastrophic success in another area.

That’s a brief description of the concept; I hope you find it useful.

Notes and links

There’s a name for the phenomenon of knowing a concept but not having a name for it; this is known in Personal Construct Theory as preverbal construing. We treat it as another form of semi-tacit knowledge.

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 17, 2016

Some myths about PhDs

By Gordon Rugg

This article covers three myths about PhDs that seem to be popular at the moment.

First myth: You have to find a PhD topic by looking for advertised PhD studentships

Second myth: You have to have a 2:1 or a distinction to get onto a PhD

Third myth: You have to start in September, or you’ve missed your chance till the next year

All three beliefs contain enough truth to look discouraging to many people who might be thinking of doing a PhD, but who don’t fit the criteria set out in the myths. However, that doesn’t mean that those myths tell the full story. The full story is longer and more complex (which may be why it isn’t as widely known as it should be) and is also more hopeful for anyone who isn’t able to follow the usual PhD route.

Before we get into the details, here’s an encouraging pair of classical pictures to put you in an appropriate mood, showing the transformation from solitary uncertainty in the wilderness to public adulation and success…

One key point before getting into the myths is that British universities are proudly independent, each with their own particular ways of doing things. This has advantages and disadvantages. From the point of view of someone wanting to do a PhD, it has the advantage that there’s probably a university somewhere whose regulations make it possible for you to do what you want via one of the routes below. From the point of view of someone writing about the myths, it has the disadvantage of making general statements practically impossible. That’s why you’ll see repeated mentions below of “some universities” and “usually” rather than simple straightforward assertions.

With that point made, I’ll move on to the myths.

First myth: You have to find a PhD topic by looking for advertised PhD studentships

You can do it this way, but you don’t have to.

One of the key problems with doing a full time PhD is getting the funding to live on while you do the PhD. There are three main ways of doing this:

Applying for an advertised funded PhD studentship on a specified topic with a specified supervisor

Applying for an advertised funded PhD studentship where the topic is left open

Finding a supervisor for the topic of your choice, and then finding funding

As you might suspect, there are pros and cons for each of these.

The first option has the advantage of being a known quantity, if your application is successful. However, you’re stuck with a specified topic and supervisor. There may be a bit of room for negotiation about the topic, but usually there’s not much room. There’s usually no room for negotiation about the supervisor. This option typically occurs when a researcher gets a grant to fund a piece of research, so there is the advantage that the researcher (who will usually be the supervisor) already has a good track record of work in this area.

The second option is highly desirable, because it combines the best of both worlds, but has the disadvantage of usually being fiercely competitive.

The third option gets you the topic of your choice, and the supervisor of your choice, but offers no guarantee of when, or even whether, you will get the funding for the PhD.

Second myth: You have to have a 2:1 or a distinction to get onto a PhD

This is the usual requirement, but it’s not an absolute barrier.

One alternative route involves doing a taught postgraduate degree. Most universities will let you onto a PhD if you have an MSc, MA, or other taught postgraduate degree. Many universities will let you onto an MSc, MA, or other taught postgraduate degree if you have a 2:2, and some will let you on if you have a Third. This route takes another year of study and expense before you can get onto a PhD, but it’s reasonably straightforward, with the only significant risk being the risk of failing the taught postgraduate degree (in which case, you need to ask how well you would have done on a PhD anyway).

Another alternative route is that most universities have a line somewhere in their admission criteria to the effect of “or other suitable evidence”. This allows the university admissions people to use their judgment in the case of applicants who don’t meet the usual criteria, but who have a strong case for admission on other grounds.

An example of other grounds for admission is publishing a peer-reviewed paper. This sounds like (and is) a pretty high hill to climb, but if you manage it, then it is a strong argument that you have what it takes for completing a PhD successfully. The disadvantages of this route include the time involved and the uncertainty involved in getting a paper accepted for publication; the advantages include being able to try this route even if you don’t have a first degree. This particular approach is not advisable if you’re working alone, because of the learning curve. However, it’s a route that some supervisors will support some prospective students on, if they’re reasonably confident that the student has what it takes.

This isn’t the same as a PhD by publication, which is a completely different thing that involves you pulling together a batch of your peer-reviewed publications into a dissertation. Some universities do PhDs by publication; others don’t.

“Other suitable evidence” can take a wide range of forms; if you’re thinking of trying this route, it’s advisable to make some enquiries first, before launching into a formal application.

Third myth: You have to start in September, or you’ve missed your chance till the next year

The answer to this one is short and simple, which is a welcome change. Most universities prefer you to start in September, because that makes the administration easier for them (and for you), but that’s usually a preference, not a necessity.

Other thoughts

I’ve repeatedly mentioned the issues of finding a supervisor and finding a topic. These are both extremely important, but getting this right involves the sort of skills that you don’t usually have until well after you finish a PhD. The irony of this is not lost on PhD supervisors.

Unpacking the full reasons for this would take several articles; fortunately, you can find an in-depth discussion of these and many other issues in The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research, by myself and Marian Petre, which is in most university libraries (usually in the short term loan section). As the title suggests, this book tells you a lot of things that you won’t find in the other books about PhDs.

I hope that this article helps you, if you’re thinking about doing a PhD.

Notes and links

Attributions for images in the banner:

By Thomas Cole – Explore Thomas Cole, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=182985

By Thomas Cole – Exlore Thomas Cole, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=183030

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Related articles:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

June 10, 2016

Research ethics

By Gordon Rugg

I have done questionable things….

Note: I’ve written this article, like all the other Hyde & Rugg blog articles, in my capacity as a private individual, not as a member of Keele University.

This article intended as an explanation of why researchers need to pay serious attention to research ethics. It’s not intended as a complete overview of all the issues that ethics committees have to consider, which would require a much longer article. For example, I don’t discuss the issue of informed consent, although this is a very important topic. Similarly, I don’t discuss whether ethical review could lead to a chilling effect on research. Instead, I’ve focused on the underlying issue of why a researcher’s own opinion about ethics isn’t enough.

Research ethics committees are interesting places. The ethics committees I attend are the only committee meetings that I actively look forward to. This is partly because everybody is focused on doing a good, professional job as quickly and efficiently as possible, and then getting back to our other work. It’s also partly because the cases that we deal with are often fascinating.

Most research students view ethics committees as an obstacle to be passed, taking precious time and effort. The reality is very different. If you’re a researcher, whether a novice or an expert, the ethics committee is a valuable friend, and can help you avoid all sorts of risks that might otherwise cause you serious grief.

In this article, I’ll discuss some ways that ethics committees help you, and some things that could go wrong in ways that you might not expect. Some of those risks are seriously scary. I’ve avoided going into detail about triggering topics wherever possible, but some of the things that go wrong with ethics might trigger some readers. By way of a gentle start, here’s a restful image of a tropical beach.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

Ethics committees are like health and safety committees in many ways. Both types of committee deal with situations where something goes wrong, and people suffer or die. Both types of committee know that these situations happen a lot more often than people realise. Also, both types of committee know that most of those situations arose when the people involved thought that they were behaving in a perfectly reasonable way, and following common sense.

I’ve spent a while working in the field of safety-critical systems. In a safety-critical system, if something goes wrong, people get injured or die. There’s been a lot of research in this area. If I had to sum up the main finding from that field in one sentence, it would be something like this:

Argument by authority, personal opinion and “common sense” tend to end badly, when safety-critical systems are involved

Most disasters involve at least one key decision where someone thought that their common sense provided the answer, or where someone thought that because they were important, they knew the answer, or where someone thought that their personal opinion was more likely to be right than the standard procedures or the professional opinions of relevant experts. Those beliefs have killed a lot of people, so the safety-critical world does not like seeing them.

The same is true of research ethics. Most of the worst abuses in research ethics over the last century were carried out by people who genuinely believed that what they were doing was self-evidently right.

If you claim that your work should not have to go through ethical review because you think it’s obviously ethical, or because you think you’re very important, or because you think that everything will be okay, then the committee won’t be impressed.

So what can ethics committees do for you?

Ethics committees can’t prevent every risk, but they can help you to avoid a lot of risks that you haven’t thought of, and to minimise a lot of risks that can’t be prevented.

The support that they provide includes support to you, but also includes support to other people who may not be immediately obvious. This support falls into four main groups:

Protecting you

Protecting your participants

Protecting third parties

Protecting your university/institution

Protecting you

When you’re focused on getting your research done, it’s easy to lose sight of the broader perspective. It’s easy to focus on your research question, and to forget about what might go wrong.

Some of the risks involve your physical safety. Those are usually fairly easy to identify, once you think about them. Usually, but not always. Having some other people look out for risks is a good idea, which is where the ethics committee is your friend.

Other risks involve legal issues, which are often difficult to spot unless you’re experienced. A classic example is that while you are collecting data, you find evidence of a participant breaking the law. What are your legal obligations in this situation? It’s a good idea to know the answer in advance, and to be legally covered, rather than discovering too late that you’re in the wrong and that you don’t have any legal protection.

Some risks are potentially life-threatening, but very difficult to spot. They’re where an ethics committee could save you from a very unpleasant or fatal situation.

Here’s an example. Imagine that you’re looking at land inheritance, and its implications; for instance, if the pattern is for the eldest son to inherit all the parents’ land, what does this do to the other children’s perceptions of the eldest son?

It’s an interesting question, and it would be particularly interesting if you could compare results across different cultures. So, you decide to set up a study that will involve data collection in two different countries. So far, it sounds pretty harmless. However, what happens if one of those countries was involved in a war a few decades ago? What often happens is that in the chaos of war, someone kills a farmer and grabs their land. How is that person going to react if you show up, investigating land ownership? In some post-conflict settings, there’s a fair chance that you’ll end up disappearing, or turning up dead in a ditch.

Yes, that’s an extreme case, and yes, that particular example is unlikely to affect the research that you are doing. However, there are a lot of other rare scenarios, and there’s a fair chance that one of them will be relevant to your research. If that does happen, you will probably be very grateful to anyone who spots the risk and gives you advance warning.

Protecting your participants

It’s also important to protect your participants. In social science research, this often involves protecting their identity. For instance, if you’re investigating anything to do with sex, religion and/or politics, your participants might be at risk if their identities are revealed. In some cases, those risks might include imprisonment and death.

Protecting identities isn’t a simple case of not stating your participants’ names. Supposed, for instance, that you describe a participant as 57 years old, male, and a senior lecturer in Politics at a leading university in a named country. How difficult would it be to identify that participant? Not very difficult at all.

It’s surprisingly easy to identify individuals from apparently trivial pieces of information, such as their likes in film and music. There was a case a few years ago where one of the major online film distributors had to cancel a competition to predict people’s viewing habits from anonymised data, because it turned out to be possible to identify many of the individuals in the anonymised data.

You also need to think about whether the task you ask them to do will be distressing to them. It may be legal, and it may not distress you, but it might easily distress someone else. This goes beyond obvious cultural issues into less obvious ones, such as phobias. If you want your participants to evaluate your website about common British spiders or about poisonous snakes, for instance, then you are likely to have several severely distressed participants to deal with before long, and several formal complaints about your behaviour to deal with after that.

There are other, less obvious risks, particularly if you’re collecting data in a culture with which you are not familiar. This is a topic that goes well beyond what can fit into this blog article; the short message is that if the ethics committee raises objections about something relating to your participants, you should pay serious attention to those objections, rather than treating them as just another annoying obstacle to your plans.

Protecting third parties

In addition to protecting your participants, you also need to protect third parties.

A fairly obvious example involves discovering that one of your participants is doing something that could cause physical damage to other people.

A less obvious but classic case is when one your participants give information about someone else that could cause distress or risk to that other person, if their identity was revealed. The information may not be about anything illegal or immoral; the key point is whether it could cause distress or risk. This can be a particular risk when you’re doing cross-cultural research, where something that isn’t viewed as an issue in one culture is viewed as profoundly shameful in another.

Protecting your university/institution

The issue of damage to reputation also affects you and your university. Some research topics and research findings are particularly likely to be mis-represented in the media and on social media. If your research is likely to end up in this situation, then being prepared can make a lot of difference.

Conclusion and further thoughts

The examples above give a brief taste of why research ethics are important, and why having a committee look at your plan is a good idea. At a practical level, they’re likely to spot potential problems that you have missed. At a sordidly self-interested level, there’s also the consideration that if something does go horribly wrong with your research, but that you have had ethical clearance for it, then you are much less likely to end up getting blamed for everything.

So far, I’ve used examples involving human participants. It’s also possible, however, for ethical issues to arise even when you’re working purely from published literature. What happens, for instance, if a historian wants to hire a research assistant to work on documents from survivors of Nazi concentration camps? Some of the stories in those documents are likely to be traumatic to whoever reads them. Does the historian need to get ethical clearance before advertising the job?

I don’t know the answer to that one, or to a huge number of other ethical questions that can affect research. Nobody else does, either. This is a field that is evolving fast in an increasing range of disciplines, including fields where ethics are a well-established issue, such as medicine. Things that were considered perfectly acceptable fifty years ago may now be considered astonishingly unethical. The world changes. We do the best we can, by reading about best practice, and by working through the implications of each case.

So, in summary: Ethics committees are your friend, particularly when they save you from risks that you haven’t spotted. They’re not perfect; no institution is. But they are staffed by fellow researchers, so they know what it’s like going through ethical review (they have to do it themselves, with their own research), and they’re on the side of good.

On which inspiring note, I’ll end.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Related articles:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

April 30, 2016

Patents, pensions, and printing

By Gordon Rugg

The Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution are often portrayed as a flowering of bright new ways of thinking about the world, shaking off the dull orthodoxy of previous centuries. Well, in some ways that’s true, but there’s also a fair amount of unglamorous practical underpinning that usually receives less attention.

This article is about those underpinnings.

One of the striking things about technological developments before the Renaissance is how many of them spread slowly, if at all. Why was that?

If you look at the question from the viewpoint of a mediaeval inventor who has just come up with a bright new idea, then you start seeing the importance of various factors that don’t get much attention in popular history.

Unglamorous and glamorous views of how inventions happen

One unglamorous question is how you plan to provide for yourself in old age. Post-retirement pensions are pretty much taken for granted now in industrialised societies. That wasn’t always the case; they’re an innovation that happened within living memory.

What happened before that? You had to fend for yourself. There were various widely-used strategies.

One was to view your children as your pension, with the expectation that they would look after you in your old age. That was fine if the children were okay with that idea, and if they had enough resources to look after you, and if you had children in the first place. With mortality rates the way that they were in the past, there were obvious risks associated with this idea.

Another was to make a lot of money, save it, and live off those savings. That was fine in principle, but if you were an inventor in the past, you rapidly hit a major problem. How could you stop people from stealing your brilliant new invention, and leaving you with nothing? In the days before patents, your options were limited.

One widely used option was to keep the key parts of your invention secret. This had obvious advantages for the inventor, but obvious disadvantages for the people who would have benefitted from your invention being more widely used.

A classic example is obstetric forceps, used by doctors and midwives in difficult cases of childbirth. These were invented in the 1600s, by the Chamberlen family. They kept the invention secret for over a century; they achieved this by requiring the room where the childbirth was occurring to be cleared of witnesses, and the mother to be blindfold, so that nobody could see the methods and tools that they were using.

The advantages for the Chamberlens were obvious, and the disadvantages to society at large were equally obvious, since the Chamberlens could only deal with a very small number of cases.

This is a classic example of how a patent system can change the world. With a reliably enforced patent system, inventors do not have to choose between the risk of poverty in old age and the well-being of millions of people; instead, they can reap the financial rewards of their invention, while society reaps the societal and medical rewards.

So, when did patents start to be used? As you may have guessed by now, they first appeared in roughly their current form in the 1450s, in Italy, at the heart of the Renaissance. Their spread was a bit uneven, and they overlapped with an often-abused system of royal monopolies in various countries, but they spread steadily, and are a key feature of modern technological society.

This story is well known to historians of technology and innovation, though it doesn’t get as much attention as it might in popular histories.

There’s another twist to the tale, though, which also deserves more attention. It’s about the low level practical issues involved in handling patents.

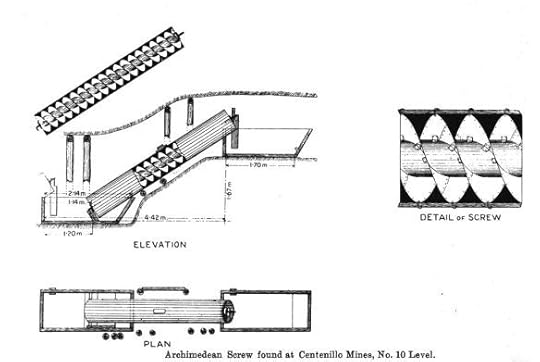

A key feature of most patents is the use of technical diagrams, to illustrate just what the invention was and how it worked. Technical diagrams are something that we take for granted now. But, if you stop and think about how they are produced, you realise that they’re critically dependent on printing technology.

Here’s an example.

By Peterlewis at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Teratornis using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7977869

By Peterlewis at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Teratornis using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7977869

This is quite a simple technical diagram. Imagine trying to copy it by hand, with quill and ink, the way it would have had to be copied before printing was invented. Now imagine trying to produce copies of a patent diagram that involves something significantly more complex. With mechanical printing, you only had to produce the master print once, and then you could run off hundreds of copies with minimal effort. This had huge implications not only for patents, but also for technical manuals and for textbooks for engineering courses. Without this technology, the Industrial Revolution would have hit some serious problems.

So, that’s how pensions and patents and printing fit together. It may not be as glamorous as the popular story of the benighted Middle Ages being eclipsed by the sheer unfettered genius of dazzling Renaissance geniuses, but it helps make more sense of how apparently unglamorous issues can have major impacts on the world.

Notes and links

Sources for banner images:

By Killian 1842 – Obstetric Forceps, Kedarnath DAS, 1929, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12969407

By Michelangelo, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15461165

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

You might also find our website useful:

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

April 17, 2016

Grand Unified Theories

By Gordon Rugg

If you’re a researcher, there’s a strong temptation to find a Grand Unified Theory for whatever you’re studying, whether you’re a geologist or a physicist or psychologist or from some other field.

That temptation is understandable. There’s the intellectual satisfaction of making sense of something that had previously been formless chaos; there’s the moral satisfaction of giving new insights into long-established problems; for the less lofty-minded, there’s the prospect of having a law or theory named after oneself.

Just because it’s understandable, however, doesn’t mean that it’s always a good idea. For every Grand Unified Theory that tidies up some part of the natural world, there’s at least one screwed-up bad idea that will waste other people’s time, and quite possibly increase chaos and unpleasantness.

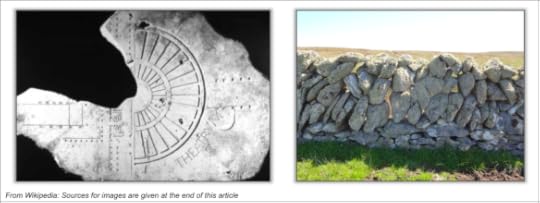

This article explores some of the issues involved. As worked examples, I’ll start with an ancient stone map of Rome, and move on later to a Galloway dyke, illustrated below.

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

In a museum in Rome, there’s a collection of marble slabs like the one in the photo on the left above. This slab has an inscribed image that looks like a classical theatre; next to the image is the word “THEATRUM”. It doesn’t take much genius to guess that this might be part of a map. They’re from an ancient map of Rome, known as the Forma Urbis Romae, that used to cover a wall of the Temple of Peace.

Once you’ve realised that the slabs form a map, you can then start working out how they should fit together to form that map, with every slab having its own unique place. Only about ten per cent of the original map has been found, but in principle, whenever a new slab fragment is found, there should be a single location in the map where that slab belongs.

That’s the beauty of a grand unified theory: A good one will correctly predict where future discoveries will fit. For example, when Mendeleyev created the Periodic Table for chemistry, it predicted the existence of numerous elements that had not yet been discovered, and more importantly, it predicted what the properties of each element would be.

So far, so good.

However, not all great unifying discoveries are the same. The periodic table predicted a range of properties for each undiscovered element. Newton’s theory of gravitation, in contrast, only deals with one property, namely gravity, and only works up to a point (which is where Einstein’s work takes over). Hooke’s law deals only with tension in springs, but does describe all springs; would that count as a grand unified theory? Pushing the issue to an extreme point, all animals could be described as land, water or air living, or as mixtures of all three; would that count as a grand unified theory?

When you look at questions like this, you realise that although the idea of a Grand Unified Theory is a nice one, it isn’t actually much use. A more useful way of looking at theories is in terms of a range of attributes. Some examples are:

Prediction versus description

Range of applicability

Universality (does it apply without exceptions, or it it just a rule of thumb?)

These are all issues that have been discussed in depth in the theory and philosophy of science, so I won’t go into them in more detail here.

What I’ll look at instead is ways in which the search for a Grand Unified Theory can cause problems.

As mentioned at the start of this article, there are strong professional temptations towards looking for Grand Unified Theories. On top of that, there are strong psychological biases that push human beings in the same direction.

One well known bias is pareidolia, i.e. seeing illusory patterns, such as faces in clouds. It’s very easy to see what looks like a pattern in a batch of data, such as recurrent clinical features in a set of patients, when in fact there is nothing more than a random cluster. This overlaps with confirmation bias, where we tend to remember the cases that fit into the pattern we created via pareidolia, and to forget the cases that don’t fit.

Another bias is towards seeing agency in actions. We tend to think that things happen because of deliberate actions by someone or something. This is a long-running problem in public understanding of how evolution works. There’s a recurrent tendency for people to talk in terms of e.g. giraffes evolving long necks in order to reach leaves in trees, as if the giraffes made a conscious decision to evolve that way.

When it goes wrong

One common outcome of the biases above is conspiracy theories. Here’s an example. You’ll sometimes see images on the Internet like the one below, described as human-made metal spheres, found in rocks millions of years old.

Moqui marbles: By Paul Heinrich – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3691420

In fact, they’re natural concretions, but because they can take such strikingly regular forms, they’re often assumed to be the product of intelligent design and of human manufacture. A wide range of conspiracy theories are based on the belief that regularities in outcomes are caused by intelligent planned action.

Medical theories

Another possible outcome of these biases involves medical diagnosis, particularly involving syndromes. It’s tempting to see clustering of diagnostic symptoms as the indicator of a single underlying disease. However, there’s a significant risk that the cluster is either purely a coincidence, or is the result of one symptom causing another.

One example that has been debated in some depth in the literature is Gerstmann Syndrome, which claims that an unusual set of symptoms are manifestations of a single underlying syndrome; sceptical researchers, however, have questioned whether the syndrome involves anything more than some patients happening to have that set of symptoms by simple chance.

Similar questions have been asked about conditions such as schizophrenia, where there have been repeated suggestions that the label “schizophrenia” is nothing more than a reification that brings together a semi-arbitrary loose collection of symptoms in a way that gives no significant useful insights into what is actually going on in the patient.

World views

One obvious type of grand unified theory featuring agency in actions is religion. Religions typically include creation myths, which explain the creation of the world in terms of a deliberate planned action by an animate agent. They disagree about whether the plan is a complete master plan like the Forma Urbis Romae, or more like a Galloway dyke, where there’s an overall concept, but most of the detail isn’t planned in advance, and can take different forms depending on chance. This disagreement is also a major issue in philosophy, particularly the philosophy of ethics. If everything is pre-determined, then there’s no obvious way for people to have free will and to make meaningful choices, in which case, concepts such as blame and crime are meaningless.

There are similar debates within other disciplines. Physics is an obvious example, but there are plenty of others. In biology, there’s a long-running discussion about whether features such as the emergence of complex multicellular life are pretty much inevitable, or whether they’re the result of sheer chance. A classic example is what would have happened if the Chicxulub asteroid and/or the Deccan Traps hadn’t wiped out the dinosaurs; would the world now be dominated by intelligent dinosaurs filling much the same niche that humans now occupy? In sociology and history, there’s been a similar discussion about the way that societies have developed; how much of this has been driven by random chance, and how much by underlying system pressures that would cumulatively push history in a particular direction?

Those are big, overarching, systematic attempts at grand unified theories. At a less formal level, there are a lot of specific beliefs that offer a far-reaching explanation of some individual features of the world. For example, there’s the just world hypothesis; the belief that overall, justice is done, and that if someone undergoes a bad experience, it will be balanced out later on by something good happening (and vice versa). Another common belief is that humans have a soul which survives after the body dies. Beliefs such as these often fit together fairly well on a small scale; for instance, the just world belief often co-occurs with the soul belief, resulting in concepts such as karma, or judgment of the soul after death, to decide whether it will be rewarded or punished in its afterlife. They don’t usually fit together very well on a bigger scale, because they create at least as many new questions as they answer (for instance, the question of where souls come from), but at a day to day level, they can provide a comforting illusion of explanation.

Closing thoughts

Grand unified theories are a tempting goal. However, that doesn’t mean that they always work.

This is a lesson that many disciplines have learned the hard way. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in particular is an area where many attempts at grand unified theories have perished ignominiously. The usual pattern is that AI forces you to work through all the details of your theory, and that the details are where the theory unravels spectacularly. Usually, you end up discovering that the problem you’re tackling has to be handled by a messy, low-level, brute force approach involving a large number of specific facts, rather than by a clean, elegant principle.

That’s not the most inspiring of conclusions. However, there’s an interesting implication that arises from it. Often, a limited-scope principle provides powerful new ways of looking at long-established fields. This happened in evolutionary ecology, when John Maynard Smith introduced the use of game theory, which provided major new insights. The same happened in politics, where concepts such as zero-sum versus non-zero-sum games gave new ways of looking at decision making.

I’ll return in a later article to the topic of widespread individual beliefs about the world, since these have far-reaching implications for the human world – in particular, for politics and religion.

Notes and links

Sources for original banner images:

Roman map image: By Ulysses K. Vestal – http://www.theaterofpompey.com/auditorium/imagines/maps/modernfur1.shtml, Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=906511

Drystone wall image: By RobertSimons – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27057613

Related articles:

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

April 1, 2016

Why are we being examined on this?

By Gordon Rugg

It’s a fair question, if it’s being asked as a question, rather than as a complaint about the cosmic unfairness of having to study a topic that you don’t see the point of. Sometimes, it’s easy to answer. For instance, if someone wants to be a doctor, then checking their knowledge of medicine is a pretty good idea.

Other times, though, the answer takes you into deep waters that you’d really rather not get into, especially if there’s a chance of some student recording your answer and posting it onto social media…

Why do some answers take you into deep waters? That’s the topic of this article. It takes us into history, politics, proxies, and the glass bead game.

Political issues

As history teachers know all too well, history is inextricably intertwined with politics. Often, there’s one version of events phrased in terms of peaceful expansion of our glorious culture and another version of the same events phrased in terms of brutal aggression and subjugation by the invaders. Which version goes into the syllabus? That’s often a political decision, rather than a decision made by historians or educators. The “teach the controversy” option is also usually political, as a way of claiming legitimacy for versions of events which don’t bear much relation to the evidence. Similarly, the “the truth lies somewhere in the middle” approach is an invitation for opposing camps to stake out increasingly extreme views, to drag “the middle” in their direction.

This issue is well recognised. Its converse, the significant absence of a topic, is also well recognised. Often, topics don’t feature in a history syllabus because society would prefer not to talk about those topics.

It’s easy to see how this principle applies to history. It also applies to other topics, though not always as obviously. In English literature, there’s a whole set of value judgments about which authors should or should not feature in the syllabus. In English language, there are similar value judgments about which dialect of English is being treated as the norm. In maths, there are decisions to make about the balance between pure and applied maths, which tie in with the expectations about the types of work for which the education system is preparing the students.

Which leads on to a different issue in education, namely proxies for future achievement.

Proxies, predictors and the glass bead game

Sometimes, students are assessed in terms of something which is a proxy and/or a predictor. A classic example is SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test) scores. The original idea behind these was that they could be used to predict how well a student would do in higher stages of the education system. So far, so good. Assessing someone’s aptitude for a particular vocation or topic has obvious and real uses.

Assessment of aptitude, however, isn’t always easy or straightforward. Often, there are very real problems in trying to measure the relevant skills directly. For instance, if you are an airline trying to assess how well potential pilots would respond to a mid-air emergency, you probably wouldn’t want to put each candidate into a real aircraft and then generate a real mid-air emergency and see what happened. Instead, you would probably use proxies, i.e. you would assess their performance in relation to things that are reasonable stand-in substitutes for that situation.

The trouble with proxies is that they can all too easily take on a life of their own. I’ll use shoe size as an example which pushes the principle to its logical, scary conclusion.

There’s a solid literature showing that height in humans correlates with social status and with salary. Leaving aside the issue of how fair that is, we can push this correlation a stage further. Since foot size correlates with height, we can predict that foot size at a given age will be a predictor of salary. Foot size, in turn correlates with shoe size. Future salary isn’t something that a school can measure directly, but shoe size is something that can easily be measured. So far, so good, more or less. So, let’s suppose that the education system decides to use students’ shoe sizes as a proxy for their future salary levels, and as a performance indicator for schools. What happens next?

What will happen next, with tragi-comic inevitability, is that schools will be strongly tempted to provide their students with bigger shoes, to improve their performance in the league tables which include shoe sizes as a measure. The bigger shoes won’t in themselves help the students’ achievement, and will probably lead to a lot of accidents and general misery. However, the schools that go down this route will do better in the league tables, and thereby get more resources from the education system, which will ironically probably help the long-suffering students to achieve more.

This particular example is intended as a satirical demonstration of a principle (though there’s the uneasy feeling that someone in central government might view it as a brilliant, cost-effective new approach to education performance indicators…)

In other cases, though, the suitability of a proxy is harder to assess. In principle, a proxy should usually be a dependent variable, where there’s only a one-way relationship between the proxy and the thing that it’s standing in for. In principle, if you change the value of the proxy, that shouldn’t have any effect on the value of the thing that it’s standing in for. Conversely, however, if you change the value of the thing that it’s standing in for, then this should change the value of the proxy. So, for instance, greyness in adult hair is a proxy for age. Dyeing someone’s hair much more grey won’t make them much more old; however, becoming much more old will usually lead to much more grey hair.

In practice, however, clear one-way causation is rare, because so many things are causally linked with each other. Finding good proxies is difficult, which produces an inherent system pressure towards using less good proxies, and towards behaviours which are geared towards those proxies, rather than the things that the proxies are supposed to be standing in for.

Which takes us to the glass bead game. In the Hermann Hesse novel of that name, the game is used in the selection and training of intellectuals. Hesse’s vision of the game is that it is based on identifying deep structure connections that help the intellectuals achieve a more powerful understanding of the world.

That’s a plausible starting point. What, though, if the game was more like Go, which is very far removed from any practical understanding of the world? If we further imagine that skill in this abstract version of the glass bead game is an excellent predictor of ability in government and administration, then performance in the game would have huge implications for an individual’s future.

Where would this lead? Because of the systems pressures explored above, schools would start teaching the glass bead game. This would create a demand for experts in the glass bead game to teach the teachers, and for courses in the glass bead game. This in turn would create a niche for university and college departments of glass bead game studies, and for conferences and journals. All of this would happen for perfectly understandable reasons, despite the initial key point that the game we’re postulating is inherently useless, with no direct applicability to the real world.

So, returning to the question that started this article, sometimes students end up being examined in something which is actually useless in its own right, for reasons which can vary between solidly sensible and cynical manipulation of the system.

As for which particular topics fall into this category of “being examined for understandable reasons although it’s actually useless”: That’s an issue outside the scope of this article…

Links and notes

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

You might also find our website useful for an overview of our work.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

March 18, 2016

What happens when you get what you wish for?

By Gordon Rugg

A favourite plot device involves someone getting what they wish for, but in a way that leaves them either back where they started, or worse off than when they started.

That plot device ties in with a couple of widespread beliefs about the world.

One is known as the just world hypothesis. As the name implies, this belief holds that there’s an underlying pattern of justice in the world, so that what you get is balanced against what you deserve. Good events, such as winning the lottery, are either a reward for previous good actions, or are counterbalanced by later disaster, to set the balance straight.

This is a comforting belief, because it implies that we don’t need to worry too much about bad things happening to us; in this belief system, we’ll get what we deserve, so if we behave well, things will be fine. There’s the added bonus that we don’t need to feel guilty about other people’s suffering, since that will also balance out one way or another.

Another widespread belief is that hubris – excessive pride or ambition – will be punished by Fate. This is very similar to the tall poppies effect, where a social group disapproves of group members aspiring to or achieving significantly more than the rest of the group.

Both of these beliefs have far-reaching implications; the beliefs and their implications have been studied in some depth, and are well worth reading about.

They’re beliefs, though. What about reality? What actually happens when people get what they wish for?

The short answer is: Usually, not much.

Lottery tickets, ancient and modern

Images from Wikipedia; sources at the end of this article

There have been several studies of people whose lives have unexpectedly and dramatically changed, whether via good events or bad. In this article, I’ll focus on what happens when you suddenly get more money.

One common finding involves hygiene factors. More money does tend to bring more happiness, up to a point. However, it’s a surprisingly low point (equivalent to having a salary a bit above the national average). It’s enough to fix the active problems in your life, which usually doesn’t take an enormous amount of money. After that, happiness levels don’t improve significantly with increased wealth.

With more dramatic changes in wealth, one consistent finding is that the those increases in wealth usually make surprisingly little long-term difference to the person’s overall level of happiness. The first year or so after a lottery win is usually turbulent, but after that, the person usually stabilises at about the same overall level of happiness that they had before the event. As you might expect, there are exceptions to this generalisation, but on the whole, unhappy people tend to stay unhappy even after becoming wealthy.

Another common finding is that people’s lifestyles often don’t undergo much long-term change after becoming suddenly wealthy.

One frequent pattern is to spend some of the money buying gifts for family and friends (for instance, a new house for the winner’s parents) and buying a new house and/or car, but then continuing to work in the same day job as before, with few changes to overall lifestyle.

Another common pattern is to spend extravagantly until all the money is gone, and then return to the same lifestyle as before.

In short, winning the lottery is not a guaranteed recipe for becoming blissfully content in a very different long-term lifestyle.

So, what’s going on?

In brief, I think that it comes back to script theory.

A script, in this sense, is a mental guideline for how to behave in a particular situation, such as how to behave when eating in a sushi restaurant. Not having an adequate script for a situation can lead to considerable embarrassment at a social level, and to disaster at a practical level if you don’t know how to handle a physical problem, so this is an important issue.

There’s a whole industry of wealth advisors, for people who have inherited or won a large amount of money, and who don’t have an appropriate mental script. This might sound like a straightforward solution to the problem of not knowing what to do, but the full story is more complex. What often happens is that the script for how to handle a large amount of money in a way that makes good financial sense clashes with the lottery winner’s long-established scripts for how I spend my money and how I spend my life.

This leads into a couple of other related concepts, namely instrumental behaviour and expressive behaviour. Instrumental behaviour is about getting something done; expressive behaviour is about showing people what sort of person you are.

So, if you’re using a life script which involves showing people what a happy-go-lucky person you are, then gambling and playing the lottery are expressive behaviours which fit well with that script. However, if you then win a fortune on the lottery, what do you do, in terms of life script? Changing life script means changing a large part of who you are, in terms of values and goals and behaviours, so most people are understandably reluctant to make that change. Even if the happy-go-lucky gambler did try making that change, they would quite likely find their new life intolerably dull, and not the “real me”. So, instead of changing to the script of sensible financial strategies, that person will probably continue as before, and will therefore have roughly the same level of life satisfaction.

When you look at the issue from this point of view, the findings about lottery winners start making a lot more sense. There’s an old truism in some areas of counselling to the effect that if people have a choice between what they’re used to, and being happy, most people choose what they’re used to.

The dynamic is very different with someone who is playing the lottery instrumentally, as a means to an end. Their response to a lottery win is still going to be hard to predict, though, because of the problem that you can’t know what you don’t know. If you reach your goal, you may find that it’s not as great as you expected it to be.

A more positive ending

Winning the lottery doesn’t guarantee happiness. However, it doesn’t guarantee unhappiness, either.

Lives can and do change for the better. This is something that can happen via quite a few different paths. One thing that you often see in biographies, for instance, is the account of how someone discovered a place or an interest or a career that they fell in love with, and that they went on loving till the end of their life.

Quite what is happening in those cases is a fascinating question. I suspect it’s something related both to script theory and to sensory diet: The person finds a lifestyle which fits both their life script and their preferred sensory diet. That’s something that I’m planning to research some day, when I have the time and the money; perhaps via winning the lottery…

On which cheering note, I’ll end.

Links and notes

Banner image sources:

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16170643

By Magnus D from London, United Kingdom – Håll tummarna!, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15810291

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

You might also find our website useful for an overview of our work.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers