Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 8

October 19, 2015

How does marking work?

By Gordon Rugg

Humour alert and disclaimer: This article is humorous, with the occasional flash of sensible content. It is not intended to be a guide to exam or coursework technique, so if you try appealing your mark by blaming this article for leading you astray, then you have even less chance of succeeding than with the excuse of only having burnt down the cathedral because you thought the archibishop was inside at the time…

I’ll start with a marking criterion that everybody knows, namely that markers don’t like Wikipedia very much. Here’s one example of why we feel that way.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/509751251548026285/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/509751251548026285/

(Used under fair use terms, as a humorous academic article.)

In case you’re wondering whether that’s just a neat bit of Photoshop, I’ve seen equally interesting claims on Wikipedia, such as an article stating that an ancient Roman politician was married to Marilyn Manson.

So, markers have reasons for mistrusting Wikipedia. What else is going through their minds, and why?

I’ll start with the legends about how marking worked in the old days. There’s a cynical view that we threw the courseworks up the stairs, and gave the highest marks to the ones that went furthest, on the grounds that they were heavier and therefore had more content. This is a gross travesty. We know as well as anyone that a lot of heavy courseworks consist of content-free padding…

There’s a more plausible legend that marking worked was based on the following half-dozen principles.

Zero to just failed: Could have been written by a passer-by who has never studied the subject.

Just failed to 2:2: A few technical terms from the lecture handouts.

2:2: Has worked diligently.

2:1: Either bright or hard-working.

Distinction: Bright and hard-working.

High distinction: Some of the concepts in this work are going to surface in the marker’s own publications at some point…

Again, this is inaccurate. Some of the more memorable fails could only have been produced by someone who had studied the subject, and who had long ago given up any pretence of caring…

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/311311392966059346/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/311311392966059346/

(Used under fair use terms, as a humorous academic article.)

However, there are some grains of truth in that apocryphal marking scheme. I’ll focus on one that offers particular scope for many students to improve their marks significantly without much effort. It’s the one about marks that are in the failing range because the assessed work could have been written by a passer-by who has never taken the course.

That’s a surprisingly common reason for low marks. Sometimes, it’s because the student never did study the subject, for whatever reason, but often it’s either because the student’s mind has gone blank due to exam nerves, or because the student has become utterly focused on telling the marker The Truth, as opposed to showing the marker their knowledge.

If you have exam nerves, then it’s well worth investigating your university’s support services. They’re usually good at helping with exam nerves; there are many effective ways of handling nerves, in a gentle, manageable way. I’ll blog about this in more depth in a later article.

Today, though, I’ll concentrate on the other reason for failing marks, namely not showing the marker your knowledge because you are instead telling them at great length about your personal convictions on the topic. This often happens, paradoxically, because the student is keen and knowledgeable about the topic.

The typical pattern goes something like this. I set an exam question which gives students the opportunity to show knowledge of individual facts, of “big picture” understanding of how those facts fit together, and of understanding the practical implications.

The phrasing about “giving students the opportunity to show knowledge” is important; that’s the purpose of the exam.

So far, so good.

Where it sometimes goes horribly wrong, though, is when the question mentions something that the student is passionately keen on, and the student focuses on telling us everything they know about it to the exclusion of everything else in the question (and in the rest of the world, come to that). The resulting answer may be the product of passion and knowledge, but if it doesn’t answer the question that’s being asked, then all that passion and knowledge is going to be wasted.

A related issue is that often these enthusiasts’ answers are phrased as if they were writing a helpful email to a friend, instead of writing a piece of assessed work. What they write may be true, but often it contains no evidence of knowledge from the course, as opposed to the knowledge that would be expected from an amateur hobbyist.

So what can you do to improve your chances?

One obvious good strategy is to make sure that you’re answering the question that’s being asked. The details of how to do that will vary between disciplines, levels, and departments.

Another good strategy that you can use in addition is to make sure that you’re showing your knowledge from the course, as opposed to what you learned on the Internet in your capacity as a dedicated fan. There’s a simple way to do that. It involves using an imaginary highlighter.

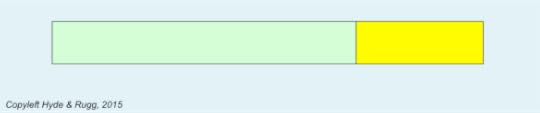

The example below shows how you do this. You go through the text, highlighting the parts that could only have been written by someone who had been on the module or course that’s being assessed. Here’s what the sample text looks like at the start. It’s from one of our other articles; the part in italics is a hypothetical sentence with fictitious references.

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/10/30/finding-the-right-references-part-3-breadth-depth-and-the-t-model/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/10/30/finding-the-right-references-part-3-breadth-depth-and-the-t-model/

Here’s the same text after the highlighting.

The parts in highlighter are evidence of knowledge that should get you marks (assuming that those parts are relevant, true, etc…)

The sentence in italics is not exactly exciting prose, but it’s densely packed with knowledge-rich content.

The linked article above explains this concept in more depth. It’s not the whole story of how marking works; there’s also professional judgment about relevance, insight, coherence, etc. However, it’s a reassuringly simple and effective start.

On which cheering note, I’ll end.

Notes and links:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

October 10, 2015

Doomsday predictions as expressive behaviour

By Gordon Rugg

There was a classic article on Pharyngula recently about a group who donned bright yellow t-shirts to announce the imminent end of the world. It’s far from the first time that this announcement has been made; it’s probably not going to be the last.

So why do people keep making this announcement? Do they really believe that this time is going to be different, or is there something deeper going on?

As you might have guessed, usually there’s something deeper going on. The same underlying principle crops up in a wide range of forms, and is particularly prominent in politics, where it can cause a lot of problems.

The explanation begins with a topic that we discussed recently on this blog, namely expressive behaviour. It then moves on to systems theory, luxury, sex and power. The end of the world is a fine, rich topic…

http://freethoughtblogs.com/pharyngula/2015/10/07/they-had-t-shirts-made/

Originally posted on: http://www.rifuture.org/world-ends-today-see-you-tomorrow.html

(Image used under fair use terms, as part of an academic article about background theory.)

Expressive behaviour is about showing people what sort of person you are. That’s very different from instrumental behaviour, which is about getting something done. Sometimes, expressive behaviour happens to align with instrumental behaviour; often, though, the two go in very different directions.

So, in the case of wearing a bright yellow t-shirt while announcing to the public that the world is going to end, you’re engaging in highly visible expressive behaviour. Whether or not the world actually does end is a completely different issue. (In case you’re wondering, there’s a literature on what doomsday believers do when the scheduled date comes and goes without the world ending. In brief, the believers reduce their cognitive dissonance by re-interpreting reality so that their self-image continues to make sense, to themselves even if to nobody else.)

However, this raises the question of why people should engage in this particular form of expressive behaviour as opposed to any of the other forms they could choose; it also raises the question of what happens when the world doesn’t end. That takes us into the concepts of subsystem optimisation versus system optimisation, of in-groups versus out-groups, and of sex, luxury and power. It also takes us into the concepts of sensory homeostasis and of optimising cognitive load, but they aren’t as glamorous as sex, luxury and power, which might be why they’ve received less attention over the years.

Expressive behaviour, subsystem optimisation and groups

Sometimes, expressive behaviour is intended as a signal for the whole world. Often, though, it isn’t. Often, it’s a signal aimed at the in-group i.e. the group with which the person identifies.

When you look at the end of the world t-shirts and placards from this viewpoint, then everything starts making a different type of sense. Standing in a public place wearing highly visible clothing and carrying a highly visible placard is a very visible signal to the in-group of fellow believers.

What do you get from signalling to your in-group in this way? For a start, you get the standard perks of belonging to a group, such as social capital – having a reputation and a set of contacts that you can draw on if you encounter difficult times, such as needing a babysitter at short notice, or going through bereavement. Group leaders usually get more. A common feature of self-isolated groups is a cult of personality around a male leader, which often ends up with the leader having sex with female followers under one pretext or another. At a more socially respectable level, prominent evangelical figures in the USA are often multi-millionaires, as a result of donations from members of their evangelical group.

So, the individual can gain a lot by sending out expressive signals to other group members. Just because it’s good for the individual, though, doesn’t mean that it’s good for society in general.

This takes us on to the concept of sub-system optimisation (e.g. making things better for a group within society) not necessarily leading to system optimisation (e.g. making things better for society as a whole). Often, what works well within a group is disastrous when applied across different groups.

A classic example involves political strategies within a democracy. Usually, politicians can gain more support from within their own party by espousing views that show them as a True Believer in the most “pure” form of the party’s ideology. However, those same views will be a liability when campaigning at a national level, because they will be viewed by members of other parties as a sign of dangerous extremism. This is why, for instance, political wisdom in the USA presidential campaigns is to play to the extreme (= “pure”) wing when campaigning for party nomination, and then to veer to the middle after gaining the nomination, when you have to play to the country as a whole.

Expressive behaviour is a prominent feature of this type of within-party posturing; there are plenty of examples of politicians making extreme claims that will go down well with their supporters, even though those claims have no chance of ever being turned into instrumental actions like passing actual legislation.

Sometimes, though, the expressive behaviour does get turned into actions, which is where it can be a real problem; again, there are plenty of examples where laws have been passed purely because politicians were pandering to the most extreme members of their own support base, even though the overwhelming majority of the country were deeply opposed to the laws in question.

Sensory homeostasis versus sensory diet

A standard feature of supervillains in the movies is that they crave the good life and power. This is usually portrayed either from a moral viewpoint (that indulgence and seeking power are bad things) or from a taken-for-granted viewpoint that any sensible person would want the good life and power.

From both the moral and the taken-for-granted viewpoint, the story stops there. However, if you ask why people would want those things, then some interesting regularities emerge.

The first regularity involves the “good life”. When you strip away the surface features (e.g. fine wines and gourmet food) then the recurrent theme is sensory loading. The “good life” involves being able to adjust your sensory input to whatever level you want. If you start looking systematically across the whole range of human senses, including proprioception etc, then this regularity makes a lot of sense of a wide spread of human behaviour, ranging from music to sexual fetishes to drug use to sport and film.

In sport, for example, one regular feature is a desire for perceived speed. The phrasing here is important. If you want actual speed, then the easiest way to get high speed is via air travel, where passenger airliners routinely travel at hundreds of miles per hour. However, you don’t see any sporting tournaments involving competitors sitting on passenger airliners. What you see instead is competitors on motorbikes or in sports cars travelling in a way that looks fast, even if it’s much slower than an airliner. With a motor race, there’s a lot of sensory load; with an airliner, there’s no perception of speed worth mentioning once you’re at cruising altitude. So, it’s all about sensory input, and about achieving particular levels of sensory input.

One obvious, but inaccurate, analogy for this is the thermostat, which regulates the heating around a preferred average. It’s not a very good analogy, because thermostats usually try to keep the temperature as close as possible to the preferred average. This concept is known as homeostasis; it’s about a system regulating itself to stay around a particular value.

However, what’s going on with sensory loading is subtly but significantly different. People don’t usually aim to stay close to a particular sensory loading. Instead, they prefer variety, within a comparatively broad range around a preferred central point.

Sensory loading appears to be better described in terms of the “sensory diet”. The core concept here is that each individual will want to include a variety of items within their “diet” rather than staying as close as possible to one standard meal. One common pattern, for instance, is a working week which is low in sensory loading, interspersed with weekends of high sensory loading.

Cognitive load

The second regularity is the desire for power. Power makes sense in terms of giving more predictable access to sources of sensory loading such as food, drink, sex and excitement; it’s a useful means to that end.

However, there appears to be something more going on with power. The perception of control is a recurrent feature in a wide range of human behaviour that doesn’t involve access to sources of sensory loading. Examples include learned helplessness (where people fail so often that they eventually stop trying, even though they could now succeed) and risk-related behaviour (where being helpless makes a risk seem much more threatening than it would if you had some control, even though the amount of damage is the same in both cases). It’s also clear that a lot of people get substantial pleasure from being in control of other people and of situations.

Here, I think that a key issue is cognitive load. Having control means that you know what will happen next; knowing what will happen next means that you have less to think about, meaning less cognitive load.

As with sensory diet, it appears that people prefer to have a diet of cognitive load, rather than simple homeostasis. Again, this makes senses of a broad range of phenomena which would otherwise look disconnected. Crosswords and Sudoku, for instance, are ways of increasing cognitive load; familiar music and meditation are ways of reducing cognitive load.

When you start thinking about human behaviour from this viewpoint, it gives you a whole new way of assessing what’s going on across a broad range of phenomena, and of seeing the underlying regularities. We’ll return to this topic repeatedly in future articles.

Assuming that the world doesn’t end before then…

Notes and links:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

October 5, 2015

Why do people treat spelling and punctuation as such a big deal?

By Gordon Rugg

This one has a nice, easy answer: Legal implications. Spelling and punctuation can have huge legal implications that in turn can have huge financial implications.

That, however, raises the question of just what those legal implications are. Again, there’s a nice, clear answer, but unpacking it will involve a couple of examples; one for spelling, and one for punctuation. Here are those examples.

Attributions for images are given at the end of this article

Attributions for images are given at the end of this article

Spelling

The first image shows the familiar yo-yo. Or should that be Yo-Yo? Nowadays, it’s yo-yo, but this wasn’t always the case, and the difference was worth millions of dollars.

Yo-yos have been around for thousands of years, as illustrated in the classical Greek image above. The name Yo-Yo (with uppercase “Y”s) was trademarked in 1932 by an American entrepreneur called Donald F. Duncan. That name was significant, because it meant that only the Yo-Yos from his company could legally be advertised with that name. This is one of the huge advantages of having a trademark; if the trademark name becomes synonymous with the produce, then it’s excellent free marketing and brand identity (e.g. Biro and Hoover). This is one reason that any company with a trademark and any shred of business sense will defend that trademark very vigorously indeed.

So what did Duncan do with his trademark? He quite frequently referred to his product in writing as a “yo-yo” (with lowercase “y”s). This was a significant issue when a competitor started describing their own product as a “yo-yo” (lowercase). Duncan lost the subsequent copyright case, because the judge ruled that he had, in effect, thrown away the protected version of the name by repeatedly treating the name as a common noun rather than a proper noun. The loss in revenue and related costs ran into the millions.

That’s an example of spelling causing problems. What about punctuation? It, too, is a rich source of woe.

Punctuation

The second image above shows Venice, a classic destination for romantic holidays.

How much does it cost to holiday there? For a very brief period, you could get a hotel room in Venice for under two euros. As you might suspect, that price wasn’t what the hotel actually intended, but when the room was advertised for 1.50 euros instead of 150 euros, the hotel had to honour the advertised price. As you might also suspect, quite a few people took them up on that offer; the estimated cost to the hotel was 90,000 euros.

It’s a more glamorous case than most, but it’s far from unique. Here’s a more impressive example, where the error cost the company about $220 million:

The Japanese government has ordered an inquiry after stock market trading in a newly-listed company was thrown into chaos by a broker’s typing error.

Shares in J-Com fell to below their issue price after the broker at Mizuho Securities tried to sell 610,000 shares at 1 yen (0.47 pence; 0.8 cents) each.

They had meant to sell one share for 610,000 yen (£2,893; $5,065). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4512962.stm

Is this fair?

The financial implications of spelling and punctuation errors can be huge. However, there are broader questions.

One obvious question involves dyslexia. A lot of people have various forms of problem with reading, writing, spelling and related issues. Is it fair to discriminate against them in employment?

A less obvious, but equally far-reaching, question involves cultural conventions. Different cultures have different conventions for indicating decimals, dates, etc. In the UK and the USA, for instance, the convention is that commas separate thousands, and a full stop (period) is used to show where the decimals begin. Is this the only convention? As you might guess, there’s a whole, rich world of different conventions, and a whole, rich world of misunderstandings arising from these differences.

So, I don’t think it’s particularly fair. The education system and the law have made some attempts to handle the situation, for instance by allowing students to use proof readers in some situations, and by making explicit allowances for dyslexia in marking assessed work. Quite what else to do about it is another question, and I don’t have a brilliant answer. However, I hope that this article will make more sense of why employers treat spelling and punctuation as such a big deal, and that it will spark some useful thoughts about how to handle this issue.

Notes, sources and links

“Yo-yo player Antikensammlung Berlin F2549” by User:Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2008. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yo-yo_player_Antikensammlung_Berlin_F2549.jpg#/media/File:Yo-yo_player_Antikensammlung_Berlin_F2549.jpg

“Canal Grande Chiesa della Salute e Dogana dal ponte dell Accademia” by This Photo was taken by Wolfgang Moroder.Feel free to use my photos, but please mention me as the author and send me a message. – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canal_Grande_Chiesa_della_Salute_e_Dogana_dal_ponte_dell_Accademia.jpg#/media/File:Canal_Grande_Chiesa_della_Salute_e_Dogana_dal_ponte_dell_Accademia.jpg

September 24, 2015

Life at uni, revisited

By Gordon Rugg

If you’re about to start your first year at university, and you’re feeling unsure and nervous, then you’ve got plenty of company. Most new students feel that way, though not all of them show it. This is a re-post of the first in a short series of articles for people in your situation, about key information that should make your life easier.

This article is about roles at university. The American cartoon below summarises them pretty accurately.

Image from Twitter

So what are the roles other than “Elmo the undergrad” and how are they likely to affect you?

Grad students: In Britain, these are usually “PhD students” or “teaching assistants” or “demonstrators” in practical classes. They’re usually cynical and stressed because of their PhDs. They usually know the university system well, and they’re very, very useful people to have as friends. (Really bad idea: Complaining to the university that they’re not real, proper teachers.)

Post-docs are next up the food chain. They already have their PhD, and they’re working on a research project until they can land a job further up the food chain. You might see post-docs around the department, but you probably won’t have much direct contact with them.

Assistant professor: In Britain, these are lecturers and Senior Lecturers and Readers and (in some universities) Principal Lecturers. These are the people who will deliver most of your lectures. Lecturing is just one of the things they do; they also do research, and income generation, and university admin, and a pile of other things. (Classic embarrassing newbie mistake: Calling them “teachers”.)

Tenured professor: The image says it all; lofty, often scary figures who give the strong impression of wisdom beyond mortal imagining. That impression is often true.

Professor emeritus: Again, the image is all too accurate. Emeritus professors often have ideas so strange that ordinary humans wonder whether they’re brilliant or completely divorced from reality. I make no comment on this.

The other articles in this series cover the main sources of confusion for students, including useful information that would be easy to miss otherwise, but that can make your life much better. I hope you find them useful.

Other articles in this series that you might find useful:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/23/life-at-uni-lectures-versus-lessons/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/27/life-at-uni-why-is-my-timetable-a-mess/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/11/06/life-at-uni-cookery-concepts-101/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/05/life-at-uni-exams/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/18/life-at-uni-after-uni/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/02/23/life-at-uni-will-the-world-end-if-i-fail-my-exams/

A couple of other articles on this blog that you might find useful as starting points:

September 18, 2015

Logos, emblems, symbolism, and really bad ideas

By Gordon Rugg

I’ve been working on logo design recently. It’s a neat example of how concepts that we’ve blogged about fit together. There are no prizes for guessing what the topic of this article will be…

Symbolism and reality; some examples Images from Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons; full attributions at the end of this article

Images from Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons; full attributions at the end of this article

Logos and related concepts, such as heraldic symbolism, have been around for a very long time. They’re a good example of something that can be both highly expressive and highly instrumental (i.e. good at sending out social signals and good at handling some functional task).

The classic example is military flags. These showed which side you belonged to, which had both high expressive value and high instrumental value.

One of the most famous flags is the Great Garrison Flag that inspired the song “The Star Spangled Banner”. It flew over the Fort McHenry garrison during the American War of Independence. At an expressive level, it had obvious symbolism. At an instrumental level, it showed who was in control of the fort, which had highly practical implications. Its instrumental function involved being clearly visible from as far away as possible, so it was huge; it was originally 42 feet by 30 feet.

In case you’re wondering whether the visibility of a flag was really such a big deal, here’s an example that changed the course of history.

One of the key battles in the English Wars of the Roses was the Battle of Barnet, in 1471. The Yorkist side was led by Edward IV. One of his opponents on the Lancastrian side was the Earl of Oxford. At a key point in the battle, Oxford’s troops emerged from the fog behind their Lancastrian allies, ready to give their support. It should have been a decisive moment. It actually was a decisive moment, but for the wrong reason.

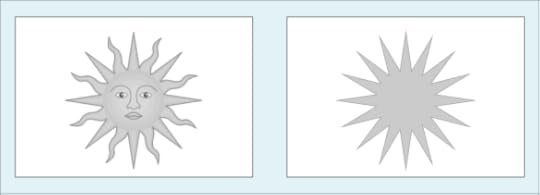

The symbol on Edward’s flag was the sun in splendour. The symbol on Oxford’s flag was the star with rays. In the fog, they looked something like this.

Opposing flags in the fog: What could possibly go wrong…? Sun in splendour image on the left from Wikipedia; attribution at the end of this article

Sun in splendour image on the left from Wikipedia; attribution at the end of this article

The Lancastrian army thought that they were being attacked from the rear by Edward’s forces, and started shooting at Oxford’s army. Oxford’s army didn’t see the funny side of the situation, and started shooting back. Both the Lancastrian army and Oxford’s army thought that they had been betrayed. Chaos ensued. Edward won a decisive victory, which turned the course of the war, leading to his eventual victory.

So, logos and symbols can have very real instrumental uses. What about their expressive uses?

Symbolism, and big fierce scary animals

The underlying regularities in choice of mascots, emblems, etc have been studied in depth by a range of disciplines, so I won’t go into this subject in depth.

As you might expect, one regular favourite is the big, fierce, scary-looking animal. Perception is more important than reality in this respect.

For instance, if you’re assessing animals in terms of how dangerous they are to humans, male lions have been a favourite element in heraldry and symbolism for millennia, but in reality they’re less dangerous to humans than hippos. Hippos kill thousands of people each year; lions kill a few hundred people each year, but you don’t see many hippos in heraldry anywhere outside Ankh-Morpork.

Similarly, if you’re assessing animals in terms of their success as a species, then beetles have been around a lot longer than lions, and will probably be around long after lions are gone, but not many sports teams would be persuaded into adopting a beetle as mascot by that reasoning.

Outward visibility of signals is also a big issue in this respect. Male lions have impressive-looking manes, which send out a strong signal of masculinity (also a favourite theme in traditional heraldry and related fields). Again, reality takes second place to outward impression; lionesses make a lot more kills than male lions, but that doesn’t count for much in traditional choice of symbols.

Game theory: is it worth the effort?

Another way of looking at logos and symbols also relates to animals, but in a very different way. Game theory provides an elegant and powerful way of assessing the strategies being used in a given situation, with particular reference to costs and gains.

One example of this involves the Red Queen Effect. Most organisations want to have a logo which will stand out and be memorable. The disadvantage of this desire becomes obvious if you try looking at the bookmark list in your browser. Because most of the sites on that list will have chosen striking, colourful designs, the result looks like a kaleidoscope that’s been on a bad acid trip. If everyone is trying to find a design that stands out from the rest, then you end up with a non-stop race for every more striking designs. Even if you just want to have a moderate, middle-of-the-road logo, you’ll still have to make your logo more striking, because if you don’t, you’ll be left behind. This effect is named after the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland, where people have to run continually in order to stay in the same place.

A sideways sidebar: Striking logos

This issue highlights one advantage of using a “timeless” design and/or an unusual design, rather than a fashionable one; by definition, fashions change fast, making this year’s fashionable design become a dated relic next year, whereas style has a much lower rate of change.

Another advantage of focusing on style involves a concept from evolutionary ecology, namely costly honest signalling.

As the name implies, this involves signals that are honest, and that involve a significant cost; the cost is usually a major factor in ensuring that the signal is honest.

There are numerous example of this principle in the animal world. A classic case is the Irish elk. The stags of this species had antlers with a span of up to 12 feet, which imposed a huge cost on their bodies. However, huge antlers were an honest signal to females that the stag was in prime condition, since an unhealthy stag wouldn’t be able to grow such large antlers. Another classic example is the peacock; yet another is the mane of the male lion, bringing us full circle back to the starting point of this article.

Costly, honest, male signals Images from Wikipedia; full attributions at the end of this article

Images from Wikipedia; full attributions at the end of this article

Honest costly signalling is very much a feature of human life. In the case of design, for instance, you can build features into the design that show its cost in terms of materials, or of time and effort, or of skill. Here’s an example. You couldn’t fake something like this; it’s an honest signal that you have a great deal of wealth and power. Whether creating it in the first place is a good idea is another question…

A really costly honest signal “BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02” by Johannes Böckh & Thomas Mirtsch – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02.JPG#/media/File:BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02.JPG

“BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02” by Johannes Böckh & Thomas Mirtsch – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02.JPG#/media/File:BasilikaOttobeurenHauptschiff02.JPG

To round off this article, I’ll return to one of the images in the banner. It’s the image of two snakes twined around a winged staff, like the image on the left below.

Count the snakes… Images from Wikimedia Commons; full attributions at the end of this article

Images from Wikimedia Commons; full attributions at the end of this article

I’m returning to it because it’s an elegant example of a risk involved in using symbolism, namely the risk of accidentally sending out a completely unintended signal. This has long been a rich source of ironic amusement to those of us who view pedantry and obscure knowledge as valuable contributions to civilisation. In the case of the winged staff with the snakes, technically known as a caduceus, there’s a widespread belief that it’s a classical symbol of medicine. In fact, in classical antiquity it was the traditional staff of Mercury, neatly described in Wikipedia as: “the messenger of the gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves”. This isn’t exactly the ideal set of associations if you’re in a medical profession; instead, the classical symbol of medicine is the Staff of Asclepius, which has one snake twining round a stick. The caduceus is traditionally the symbol of commerce and negotiation. I will refrain from comment…

Notes, sources and links

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sun_of_York.svg

“Lion waiting in Namibia” by Kevin Pluck – Flickr: The King.. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lion_waiting_in_Namibia.jpg#/media/File:Lion_waiting_in_Namibia.jpg

“Goliath beetle”. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goliath_beetle.jpg#/media/File:Goliath_beetle.jpg

“Caduceus large” by Rama – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caduceus_large.jpg#/media/File:Caduceus_large.jpg

“Okonjima Lioness” by Falense – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Okonjima_Lioness.jpg#/media/File:Okonjima_Lioness.jpg

“Giant deer” by Bazonka – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giant_deer.JPG#/media/File:Giant_deer.JPG

“Paonroue” by Jebulon – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paonroue.JPG#/media/File:Paonroue.JPG

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caduceus_Detail_Of_Giuseppe_Morettis_1922_Bronze_Hygeia_Memorial_To_World_War_Medical_Personnel_Pittsburgh_PA.jpg“Aeskulapstab 5779” by Andreas Schwarzkopf – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons –

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aeskulapstab_5779.jpg#/media/File:Aeskulapstab_5779.jpg

Book:

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

September 12, 2015

Beyond the 80:20 Principle

By Gordon Rugg, Jennifer Skillen & Colin Rigby

There’s a widely used concept called the 80:20 Principle, or the Pareto Principle, named after the decision theorist who invented it. It’s extremely useful.

In brief, across a wide range of fields, about 80% of one thing will usually come from 20% of another.

In business, for example, 80% of your revenue will come from 20% of your customers. In any sector, getting the first 80% of the job done will usually take about 20% of the resources involved; getting the last 20% of the job done will usually be much harder, and will take up 80% of the resources. The figure won’t always be exactly 80%, but it’s usually in that area. Good managers are very well aware of this issue, and keep a wary eye out for it when planning.

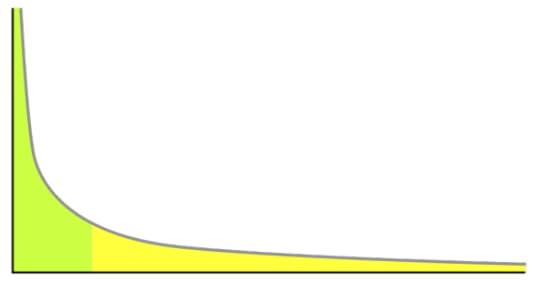

Here’s a diagram showing the principle. It’s pretty simple, but very powerful. However, that doesn’t mean that it’s perfect. It can actually be developed into something richer and more powerful, which is what we’ll describe in this article.

A more powerful version

The 80:20 Principle divides the world into two categories. However, the world isn’t usually that simple. Usually, there are more than two common categories that you need to be able to handle. The number usually isn’t enormous; it’s usually only a handful of categories, but that’s still more than two. So, is there a neat way of extending the 80:20 Principle to include those other common cases?

One logical next step is to ask whether the 20% itself follows the 80:20 principle, with a small sub-minority within it. The answer is that usually it does. And, to answer the follow-up question, yes, that small sub-minority will usually itself contain an even smaller minority. Here’s an illustration showing those layers of minorities.

So, a large majority of cases fall in the light green category on the left. A fair-sized minority fall in the yellow category. A noticeable but smaller minority fall in the beige category, and a very small minority fall in the red category at the right.

The proportions that we’ve used above are 70:20:9:1.

These proportions aren’t completely arbitrary. We’ve chosen them via a combination of real-world examples and of statistical principles, which we’ve unpacked in the notes at the end of this article. The actual distributions that you’ll probably see in real life will probably not be exactly the same as this, but they’ll usually follow the same overall pattern. (So, don’t get hung up on the precise figures; the key point is the general principle.)

In brief, there’s usually one very common category, then a fairly common second category, and then a few less common categories, followed by an assortment of rare or very rare categories. This type of distribution has been extensively studied in statistics and related fields, via concepts such as normal distributions and power laws, which we briefly describe in the notes at the end of this article.

So what?

Here’s an example of this principle in everyday life. It involves people’s surnames.

Very common: Surnames look straightforward at first glance. You ask someone for their surname; they answer with a single word like “Smith” or “Patel”. Most of the time, it’s straightforward.

Fairly common: Quite often, though, it’s not so straightforward. A common case is married women who use their married name for everyday purposes, but who continue to use their maiden name for professional purposes. Similarly, a lot of authors, actors, etc use a pen name, or stage name, etc.

Less common: There are also other cases which are not so common, but which are still far from rare. A classic example involves patronymics, such as de Vere, or ap Rhys, or ní Gabháin. Unlike “Smith” or “Jones” these names each consist of more than one word.

Rare: Some answers to the name question will be along the lines of: “Sorry, it’s not that simple”. For example, a lot of Indonesian names consist of a single word, rather than the more familiar “personal name plus family name” combination. Sometimes, the answer will be “Don’t know”. This can happen when relief agencies are trying to deal with a young, lost, child. It can also happen when the emergency services are dealing with someone unconscious who isn’t carrying any identification.

This issue has very real practical implications. One example is passport control when you’re traveling; if some of your identification uses one version of your name, and the rest uses another version, you’ll probably have to spend a lot of time trying to explain this to sceptical immigration officials. Another example is official records, such as bank and health records, where similar problems can easily arise.

If you’re dealing with customer or client records, then you’ll also encounter very similar complications with just about every other data field you have to deal with. The less common the complication, the longer it will usually take to sort out, and the greater the potential for chaos, if different people in the organisation are making different judgment calls about similar cases. In a worst case, this can lead to lawsuits because you’re treating people inconsistently, or to death if confusion with medical records leads to doctors being unaware of critical information about a patient.

So what can you do about this?

You can reduce this problem significantly by using a simple model. We’ve named it the SALT model, for:

S Standard process, for the standard, very common, cases

A Alternate approach, for the fairly common alternatives

L List of the less common alternatives

T Trained professional judgement, applied to the rare cases

From the viewpoint of someone handling a customer query, for the sake of example, it would work like this.

Standard process: A customer asks a common, straightforward question, and you tell them the standard answer, swiftly and easily, from memory.

Alternate approach: Your organisation trains you in how to handle the handful of fairly common alternatives to the standard process. You will encounter these cases often enough to keep your memory fresh as regards the correct way to handle them.

List: Your organisation provides a list of the less common alternatives, with the policy of handling each one. When you encounter a case you haven’t been trained in, you look for it on the list.

Trained professional judgment: If you encounter a case that you haven’t been trained in, and you can’t find it on the list, you hand the case over to a trained professional. Where possible, they will add their decision about the case to the list, so that future cases are handled in the same way. Where this is not possible, the organisation has a standard legal disclaimer saying, in effect: “We’re treating you as a one-off special case, without any legal implication that the way we treat you can count as a precedent in future cases”.

Further thoughts

This approach can easily be integrated with some other useful concepts.

One is optimising the standard process, by making it as efficient as possible. When you’re dealing with large numbers of cases, which is what the standard process does, then even a small improvement in efficiency soon mounts up. This type of optimisation is a key part of Total Quality Management in the best manufacturing processes, and also in software design for systems that need to handle a very large number of transactions. Shaving a second off the time for an average online process can make a very big difference when spread across a large system.

Another is systematically deciding when to base your processes on knowledge in the head as opposed to knowledge in the world. Training a member of staff in a given procedure costs time and money. However, if the staff member can then handle that procedure efficiently from memory (knowledge in the head), they can work faster and better than if they had to look up the relevant information online or in a handbook (knowledge in the world).

The “list” approach overlaps with the issue of information representation, which has featured repeatedly in previous articles on this blog. The list needs to be formatted in such a way that it can be used swiftly and easily by staff. This is a well recognised problem in software design, because there is no single best way of structuring a list. For instance, if you structure a list alphabetically, you hit the problem of different names for the same concept; if you structure it from most common to least common cases, then the user won’t know where to look for the case that they’re dealing with, and will have to work through the entire list item by item.

A fourth significant point about this approach is that it reconciles the apparent conflict between procedures and professional judgment. This is a long-standing problem in professions such as medicine and academia, where professional judgment is a crucial element, but can conflict with the drive towards standardisation that is a central feature of successful bureaucracies.

Implications

This approach has some major implications for best practice in public policy, as well as for individual organisations.

A key implication is that any new policy should include an explicit statement of how the policy should handle the first three categories (standard, alternate, and list). A related implication is that any new policy should explicitly say what should go into the standard approach, the alternate approach, and the list.

For instance, many government initiatives in recent years have implicitly been based on the assumption that everyone is literate, and that everyone has a bank account, with only a tiny minority of people not fitting those descriptions. The reality is quite different, and the gulf between assumptions and realities has often meant that policies were unworkable from the start. Governments have to govern for everyone, not just for the most common categories; the way that a nation treats its marginal minorities says a lot about how civilised it really is.

Simply having to list the less common cases as part of the policy creation, preferably with some reality-based research into how common each of those cases was, would have avoided quite a few policy fiascos, and a lot of human tragedy for the people caught in the chaos of botched systems.

Another, less obvious, implication was pointed out by our colleague Steve Linkman, in Computing at Keele. The people in the less common and rare categories will usually have experienced a lifetime of problems with systems that don’t have a neat, simple way of handling them. Vegans have had years of explaining that they’re not the same as vegetarians; people with surnames like “ní Gabháin” have had years of seeing their name mangled by systems that were designed for names like “Smith”; people with food intolerances have had years of being treated as just fussy eaters.

That sort of experience is likely to leave people tetchy when they encounter yet another case of a system causing them problems. That can in turn easily lead to confrontations between the individual and the organisation that is deploying the system – for instance, long-suffering receptionists and front office staff.

One simple way of addressing this is to include awareness training as part of the training for alternate cases, so that staff don’t make ill-advised jokes or comments to people in unusual categories. A little effort here could go a long way, in terms of helping improve people’s experiences and people’s lives.

On which cheering note we’ll end.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

The statistical background

The numbers we’ve used are inspired by the figures for statistical normal distributions. If something is distributed on a normal distribution, then most cases are near the middle, with fewer cases occurring as you move further away from the middle. For instance, most people are about average height; quite a few are a bit above or a bit below average height; a few are very tall or very short; and a very few people are extremely tall or extremely short.

If you want to translate concepts like “quite a few” into actual numbers, then there are elegant statistical ways of doing so. This is extremely useful for all sorts of purposes, such as predicting what proportion of your customers will want a particular size of a product.

In statistical terms, if the distribution follows a normal curve, then about 70% of the cases will be within one standard deviation of the mean (a 70:30 distribution). Of the remaining cases, most will be between one and two standard deviations from the mean, dropping off to about 1% of cases being more than one standard deviation from the mean.

We haven’t tried to follow the normal distribution exactly; this article is about a rough approximation that is fairly easy to remember, and about ways of handling that distribution of cases, not about precise prediction or statistical detail.

You also see a very similar distribution in a form of statistics known as Principal Component Analysis (PCA). When you examine the relative effects of multiple causes of a phenomenon, you usually find that the first few causes account for the vast majority of the effects, with the other causes only contributing very minor effects.

Another concept which shows similar principles is a power law. Power laws crop up in areas as different as city sizes and earthquake severity.

In power law distributions, you usually see one category that’s much more common than the others (the one at the left of the diagram) followed by a few categories that drop steeply from quite common to moderately common, and then a long tail of categories that range from uncommon to very rare.

“Long tail” by User:Husky – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Long_tail.svg#/media/File:Long_tail.svg

“Long tail” by User:Husky – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Long_tail.svg#/media/File:Long_tail.svg

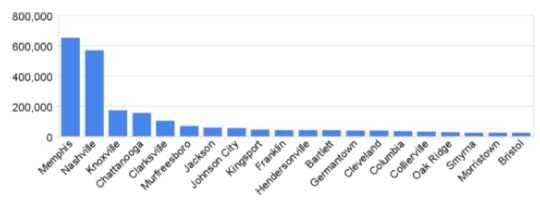

Here’s a real world example.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tennessee_cities_by_population.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tennessee_cities_by_population.png

The diagram shows the sizes of cities in Tennessee. The first two are large (more than 500,000 inhabitants), but after them, the size drops off rapidly, with the majority being well below 100,000

So, in summary, the overall principle we’re describing is very widespread, and the SALT approach gives a richer, more powerful way of handling it than the 80:20 principle.

September 3, 2015

Instrumental and expressive behaviour

By Gordon Rugg

There are a lot of very useful concepts which are nowhere near as widely known as they should be.

One of these is the concept of instrumental versus expressive behaviour. It makes sense of a broad range of human behaviour which would otherwise look baffling. It explains a lot of the things that politicians do, and a lot of the ways that people act in stressful situations, for instance.

This article gives a short overview of the traditional version of the concept, and describes how a richer form of knowledge representation can make the concept even more useful.

Humans being expressive and instrumental

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

The concept of instrumental versus expressive behaviour (also known as communicative behaviour) has been part of sociology and social psychology for a long time, and tends to be taken for granted in those and related fields.

Instrumental behaviour is about getting something done. For instance, eating a meal because you’re hungry is instrumental behaviour.

Expressive behaviour is about sending out social signals. For instance, a politician eating a meal with supporters despite not being hungry is sending out a social signal, showing their allegiance with those supporters.

So far, so good. However, a lot of things can, and do, go wrong when these concepts play out in the world.

One example is bedside manner in the medical world. The medical staff are, understandably, primarily focused on instrumental behaviour that will keep the patient alive and help the patient recover. However, this can often come across to the patient as a significant absence of expressive behaviour; the patient therefore perceives the medical staff as uncaring.

Another example is politicians engaging in expressive behaviour that is apparently useless in practical terms, such as voting for a particular policy that has no chance of ever being enacted, to send out a signal to their supporters. This overlaps strongly with the concept of sub-system optimisation not necessarily leading to system optimisation; what’s good for one politician, or for one political party, may be disastrous for the country or the world as a whole.

If you deal with people at times of stress, such as students around exam time, you see another crossover between instrumental and expressive behaviour. When people can’t solve a problem via instrumental behaviour, they often try using communicative behaviour instead, to signal that they care about the issue and are trying hard. This can easily be misconstrued, and perceived as a sign of incompetent cluelessness, because they’re not doing the practical things that would solve the problem.

That’s a swift overview of instrumental behaviour, expressive behaviour, and how they can make sense of much apparently irrational behaviour.

It’s a useful distinction, but it has problems. For instance, if a politician is deliberately engaging in an expressive behaviour in order to achieve the practical goal of being voted into power, does that mean that the expressive behaviour is itself instrumental?

The answer is yes, this behaviour is both expressive and instrumental. This doesn’t need to be a contradiction. One simple way of showing these concepts in a more powerful way is to treat them as two axes on a graph, where a given behaviour can range from low to high in how expressive it is, and from low to high in how instrumental it is.

Here’s an example.

It’s the same formalism that we’ve used previously for various other topics, such as false dichotomies in education theory, handedness, and gender theory.

This simple transformation gives another dimension to an already powerful concept.

This raises the question of just how many other useful concepts could be made even more powerful by using a richer representation. We don’t know the answer yet, but we’re working on it; it looks like being a big number….

Notes, sources and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

Sources of images in the banner

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medical_X-Ray_imaging_PTL06_nevit.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:People_hugging_in_the_beach.jpg

“20090105 PelolsiMeeting-3234” by Pete Souza – Obama-Biden Transition project from flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20090105_PelolsiMeeting-3234.jpg#/media/File:20090105_PelolsiMeeting-3234.jpg

Links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

August 27, 2015

The band with the tractor drum kit

By Gordon Rugg

If you’ve ever wanted to see a band with a tractor drum kit, accompanied by the Red Army Choir and Russian dancers in full national costume, performing “Delilah,” then here’s your chance…

The inimitable Leningrad Cowboys, poker faced as ever (unlike the dancers, who are clearly having the time of their lives, and who are also clearly trying very hard not to laugh).

August 20, 2015

The Myth of Business Efficiency

By Gordon Rugg

There’s a widespread belief that the public sector has much to learn from business, in terms of efficiency. There’s also a widespread belief that Bigfoot exists. One of these beliefs has some correspondence with reality, and has a fair chance of making the world a better place; it’s not the one about business efficiency…

Images from Wikipedia; full credits at the end of this article.

Survival skills in a competitive world

Businesses exist in a competitive world; this might be taken to imply that they know a lot about survival.

When you look at the numbers, though, businesses look like raw amateurs in the survival game. For starters, only about 50% of businesses survive their first few years. That doesn’t inspire confidence.

A plausible counter-argument is that the high attrition rate among new start-ups just reflects amateurs being weeded out, and that real businesses survive much better, once they’re past the critical first few years. That’s plausible, but how does it match up to reality?

If you look at a list of the oldest businesses in the world, it looks pretty impressive at first sight. There are about sixty businesses that date back to before 1300. However, when you examine that figure more closely, it looks much less impressive. The vast majority of those businesses are small family firms, and are inns, hotels, breweries, vineyards, and/or specialist suppliers of religious goods, such as makers of temple bells. There are just a handful that are decent-sized commercial operations.

A counter-argument is that surviving from before 1300 is pretty impressive regardless. Again, though, when you look at the broader context, that argument doesn’t stand up for long. There are about a dozen universities that have been continually in operation since before 1300, and there are schools in the UK that have been operating continuously since the seventh century; the King’s School at Canterbury has been open since 597. When it comes to long-term survival, academia knows a thing or two.

The same is true of local government. For instance, if you’ve ever wondered why a lot of English towns have the word “market” in their name, it’s because of 13th century government policies, which regulated official markets. Some examples: Market Drayton received a royal charter in 1295, authorising it to hold a market each Wednesday. It still holds a market every Wednesday. Market Deeping has had a regular market since at least 1220. Market Harborough has had a market every Tuesday since 1221.

That’s just the official markets. The towns themselves have been around for much longer. The vast majority of the towns listed in the Domesday Book of 1077 are still in existence, and were long established at the time of Domesday, with many of them going back well into Saxon times. Each of those towns would have a continuous management system of mayors, councils, etc, that also went back to Saxon times. So, local government has a pretty impressive track record in terms of survival skills, both in terms of survival rates and in terms of longevity.

Overall, then, businesses don’t have an especially impressive record in terms of long-term survival skills. Perhaps, though, they’re more impressive in other ways?

Nature red in tooth and claw

A common belief is that the business environment is driven by the survival of the fittest. This is a phrase that tends to drive evolutionary ecologists, who know about competition in nature, to rage or melancholy.

In 19th century English, the phrase “survival of the fittest” was ambiguous. It could mean either “survival of the best fitting” (i.e. best fitting to the environment) or “survival of the most physically fit”. The first meaning more closely reflects how evolution actually works. Unfortunately, the second interpretation, which is a mangled half-truth, has become very widespread. That’s understandable; it’s much more flattering for a chief executive to imagine themselves as a strong, athletic top predator than just as someone who happened to fit well with the environment.

Again, if you look at the numbers, you soon find that the popular image of “survival of the most physically fit” doesn’t hold up very well to the evidence.

For instance, cheetahs are the fastest land animal, and are often cited as examples of nature producing perfection.

In reality, though, cheetahs haven’t done too well in evolutionary terms. The surviving species went through a population bottleneck a few thousand years ago, with just a tiny number managing to survive; this has left them with very little genetic diversity. The American cheetahs became extinct around the same time.

Being a fast, athletic predator isn’t a guarantee of evolutionary success; slow, unathletic, inoffensive species such as the brown-throated sloth and the nine-banded armadillo are doing a lot better than cheetahs. If you’re looking at widespread, long-term survival as an indicator of evolutionary success, then the real success stories are much less glamorous; for instance, cockroaches have been around since the time of the dinosaurs, and barnacles have been doing very nicely for themselves since about 500 million years ago.

Overall, then, the idea that competition leads to the selection of lean, muscular, physically fit champions is a long way from reality.

Organisational efficiency

So, business can’t teach a lot about how to survive in the long term, and the “competition leads to fitness” claim is seriously misleading. It can be argued that these are both missing the point of what business is really about, namely organisational efficiency.

Unfortunately, this argument also falls apart fairly swiftly.

Within every organisation there are roles and people; within the overall system of the organisation, these roles and people are subsystems. It would be nice to think that what’s good for the subsystems is also good for the system, and vice versa. However, that’s not actually the case.

Often, what’s good for the individual within an organisation is often bad for the organisation, and vice versa. A classic example is economic crashes caused by personal bonus systems that encourage individual staff members to engage in behaviour that rewards them well, but that is disastrous for the bank or finance company that they work for. Often, there’s no long-term cost to those staff members when the organisation collapses; by that point, many of them will have made enough money to live comfortably for the rest of their lives.

Even when a business is demonstrably efficient in terms of its internal processes, this often comes at a cost to someone else. These often take the form of externalities, i.e. costs such as pollution costs that are borne by other parts of society.

Another form of broader cost comes from business monopolies, which are efficient from the viewpoint of the monopoly holder, but are bad news for everyone else if the monopoly holder uses that power to inflate prices.

A third form of broader cost from efficient businesses is gaps in coverage. A classic example is “orphan diseases”. These are diseases which don’t affect enough people to create a financially viable market for a pharmaceutical company. This may make financial sense for a business, but it’s not much of a prospect for the people suffering from those diseases.

If you’re a business, you usually have the option of deciding on your market. If you’re in the public sector, you don’t have that luxury. Local government has to provide services for everyone; public healthcare has to provide treatment for everyone. This means having to deal with a significant proportion of difficult cases that require a lot of time and resource, and this often means creating processes and procedures specifically to handle those difficult cases.

From the outside, those processes and provisions can look like bureaucratic inefficiency; from the viewpoint of the people on the inside, they look a lot more like having a sensible, thought-through set of strategies in place, so that the system can get the job done when the rare cases come along.

Closing thoughts

One piece of advice that I give my students about efficiency is this: If you ever find yourself in an organisation that prides itself on its efficiency, then start looking for a job somewhere else as soon as possible.

The reason is that “efficiency” is a much misused word. Efficiency is usually viewed as a self-evidently good thing. That isn’t always the case.

With organisations that pride themselves on their efficiency, for instance, “efficiency” often takes the form of not having any superfluous staff. That’s fine while everything is going well, but what happens when winter flu does its rounds, and staff call in sick? What happens is that there’s nobody who can cover for them, because everyone’s already fully occupied with their own work.

This is why sensible organisations that want to stay in existence for a reasonable length of time will have some slack in their system, either by deliberate design, or by letting entropy and human creative laziness take their toll. In the short term this slack is inefficient; in the long term, it’s vital.

So, “efficiency” is a concept to be treated with caution. As a rough rule of thumb, if you can’t explain the difference between system optimisation and subsystem optimisation, you should be wary of the term “efficiency”.

Where does this leave us in terms of the original idea about the public sector having much to learn from business? In brief, it’s an idea that’s fractally wrong; the more you examine it at multiple levels, the more you find wrong with it. However, it sounds good, and it sounds truthy, and it flatters the egos of rich people in industry who make donations to political parties, so it’s currently fashionable.

That’s not the most encouraging of notes on which to end, so here’s a nice, comforting picture of two sea otters holding hands, so they don’t drift apart in their sleep. Sometimes the survival of the fittest produces outcomes that leave you with a good feeling…

Images from Wikipedia; full credits at the end of this article.

Notes and links

Bigfoot:

No, I don’t think that Bigfoot exists, but I do think that a large wild bipedal non-human ape is ecologically plausible, and that some of the footprint evidence initially looked plausible. The debate about Bigfoot has also got at least some people thinking about how we should treat non-human primates, which I count as a good thing.

Picture credits:

“Cheetah Kruger” by Mukul2u – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cheetah_Kruger.jpg#/media/File:Cheetah_Kruger.jpg

“Bradypus variegatus” by Christian Mehlführer, User:Chmehl – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bradypus_variegatus.jpg#/media/File:Bradypus_variegatus.jpg

“Sea otters holding hands, cropped” by Joe Robertson from Austin, Texas, USA; cropped version by Penyulap. – Cropped from File:Sea otters holding hands.jpg.. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sea_otters_holding_hands,_cropped.jpg#/media/File:Sea_otters_holding_hands,_cropped.jpg

Background context:

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

August 14, 2015

Academic Publishing: understanding the options

Guest Post by Daniel O’Neill

Publishing research can be puzzling for beginners. This article looks at academic publishing from the point of view of a PhD researcher.

Publishing for the Researcher

I undertake research in construction and surveying. I wouldn’t describe myself as a veteran publisher of research. I knew nothing about publishing five years ago, and what I now know is limited in comparison to more seasoned researchers. I am currently writing my fourth paper from my PhD. I have written many magazine articles outside of my academic writing. The magazine articles were easy to write. I find it easy to write in an active and informal style. Articles are relatively easy to publish as websites and magazines seek and need free, mediocre to good material for publications. The researcher wants to attract attention to what they know, or what they are researching, and the website or magazine wants free content, or in some cases a fee is paid. The serious, formal, academic papers are more difficult to publish.

Options: Journals and Conferences

There are two options in publishing research papers, firstly publishing in a journal, secondly publishing at a conference. The journal route offers you a chance to present your research in an international journal. If you are interested in the process of publishing in academic journals, Abby Day’s book “How to Get Research Published in Journals” is a great read for beginners and experienced researchers alike. Generally, top publishers do not let the public free access to the online journals, but they will allow restricted access and some free samples. The publishers sell papers online: per issue or per paper. The price varies depending on publication, and popularity. To purchase one paper online can cost around €25 to €32 (approximation).

There is normally a long lead-in time for publishing in a journal. This is due to the number of papers being submitted. Journals publish a number of issues a year: annuals (common in esoteric areas), four, five, six or even ten issues. Depending on the reviewers’ requests for changes and corrections it is common to wait over a year to get published; however, there are calls for papers, when an issue with a specific theme is being published. The journals retain the rights to your material allowing the publisher to publish in an issue; unless you purchase the rights in which case it is openly available online. Publishers may also allow you to publish your own pre-publication version online. See the publishers’ copyright rules online for more detailed information. You will possibly read about ‘Green Access’ and ‘Gold Access’.

The process is not as basic as I have previously described and Day’s book goes into the process in detail. The publisher wants the journal to make money. The author wants their research exposed to the audience. The readers want to obtain information, more precisely cutting-edge research in their field, or they are looking at moving into another field of research and they are looking for samples. There are a number of players on the publisher’s side: the editor of the journal, assistant editors, the reviewers, and publishing support staff. The journal has to earn a profit, and be deemed a high quality publication in order for the reader to desire its information and purchase it, and for writers to want to publish in it. The idea of this is reasonable. Everybody gets something from the first viewing, the writer, the reader, the publisher. The top journals in my disciplines (construction and surveying) have a lot of papers sent to them, there is strong supply, and those not deemed suitable are rejected, and the authors go to another journal, possibly a lesser known publication. However some authors aim for a specific journal due to its readership – maybe experts and professionals in a specific field.

Conferences are great platforms to get “live” feedback from your research findings. When you present at a conference, you generally showcase what you have done in front of other researchers. The crowd can be as small as twenty and as big as a few thousand. Conferences are held all over the world. Journals are generally cheaper than conferences when it comes to publishing your research. Regarding conferences, this cost does not take into account travel to the location, accommodation and food. Lots of conferences have a conference dinner. This is usually lavish, with a three or four course meal, and after dinner entertainment; not forgetting other minor meals and drinks. This extravagance adds significantly to the cost. Conferences give people a chance to interact with each other, network with possible future employers and discuss the research being presented.

I have been thinking of the process of publishing material recently, as I have papers I would like to publish. The cheapest and most effortless answer is to publish it on an online platform for no direct cost (unreasonable/bad idea); however this would not get my research to the general public (researchers and professionals in construction and surveying) that have interest in it, as very few people would specifically search online for my research, but would go to a specified location such as a conference or journal website for such research. This is the card conference organisers and journals have that make them required – they offer you a platform, an outlet, at a significant financial cost in the case of conferences to you the author! The main reason an author would want to go to a conference is to get their research published; some want the extravagant dinner, and the entertainment also, and that’s fine too!

The ‘Reality’

There are people however, who just want to get their research published on a familiar and popular platform. As I have stated journals and conferences can be expensive, specifically for a postgraduate student with a lot of material to publish. The cost of £650 plus, if you have to travel and stay, for a conference might not be much to an established university professor, with a good income, and one paper to publish. However, it may be a considerable sum for a researcher on a scholarship or those self-funded, with four to six papers to publish. I think there should be a recognised alternative. I have been reading a lot about open access and other alternatives, and the models behind them, but I have not found a replacement for the traditional options. It is a time of great discussion in the academic world with regards the best model for publishing. It is difficult to say what would be best for the authors, academic readers, the general public, publishers. There are many sub-areas in this article which could be developed into more detailed articles. I have briefly discussed the traditional options here. The books below cover academic publishing in greater detail. Links are given below to articles on publishing. Do some further reading before deciding where to publish your research.

Daniel O’Neill is a PhD graduate, with academic research interests in construction. His PhD was on the retrofit of local authority housing.

Links and references

Read more about publishing in academic journals in Abby Day’s:

How to Get Research Published in Journals:

There’s more about the realities of a PhD in this by book by Gordon Rugg & Marian Petre:

The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Unwritten-Rules-Research-Study-Skills/dp/0335237029/ref=dp_ob_image_bk

Recommended articles:

http://www.publishingtechnology.com/2015/01/five-predictions-for-academic-publishing-in-2015/

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers