Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 11

March 7, 2015

Problem solving skills: What are they?

By Gordon Rugg

There is a general consensus that problem solving skills are a Good Thing. There���s general consensus that the education system needs to encourage them.

So far, so good. The consensus doesn���t go much further, though. It rapidly bogs down in long-running arguments about what problem solving skills actually are, and about how to measure them, and how to teach them. Those arguments follow a familiar pattern, with disputes about the True Definition, and invocations of Great Thinkers such as Socrates and Plato and Wittgenstein. The fact that those arguments have been rumbling on inconclusively for decades is a strong hint that maybe they���ve been framed in the wrong way from the outset, and that framing them differently might be a good idea.

That���s what this article is about. It describes more productive ways of handling these concepts, with particular reference to definitions, education theory and educational practice. It���s based on what happened the field of Artificial Intelligence tried to produce software that would find creative solutions to real world problems. It���s a story of how re-framing the issue with subtly but profoundly different concepts gave a powerful, efficient set of solutions that changed the world. It���s a story that most people have never heard of. It���s also a story that should transform the way that we tackle this aspect of education.

���It���s really quite simple������ “Viejos mineros asturianos” by Jomafemag – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons (link at end of this article)

“Viejos mineros asturianos” by Jomafemag – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons (link at end of this article)

For generations of schoolchildren, the word ���problem��� is forever associated with an opening line about some number of men taking some number of days to dig a hole. The responses to this opening line fall into three groups:

���This is going to be a simple arithmetic problem���

���They might as well ask me how long it will take six beetles to walk across a barrel of tar wearing hobnailed boots on a Tuesday in Hanoi���

���Yes, but calculating how long it will take to dig the hole with a different number of men isn���t that simple, and anyway, why is it only men who dig holes in these problems?���

The traditional education system handled these groups of responses in simple, time-honoured ways.

The ���It���s simple arithmetic��� children produced the approved answers and received good marks.

The ���It might as well be beetles in hobnailed boots��� children produced guesses or no answers, and ended up with poor marks.

The ���It���s not that simple, and anyway��� children were told to pretend that life really was that simple, and were labelled as troublemakers.

This approach had a lot of problems, but it did have some sensible-looking foundations. There clearly were demonstrably correct solutions to the problems being posed, if you accepted the simplifying assumptions; the mathematics clearly worked. Those solutions were based on demonstrably correct logic and mathematics; they weren���t arbitrary social conventions. It was also clear that some people were better than others at solving this type of problem.

The implication was that skill in using logic to solve these small problems would transfer in some way into skill in solving bigger, real-world problems. In some cases, this was clearly true. A lot of civil and mechanical engineering, for instance, involves substantial amounts of mathematical calculation.

The situation was similar with regard to logical puzzles, such as the Tower of Hanoi. This is a game which requires the player to move hoops from one post to another via a limited set of permitted moves. Again, some people are much better at this than others.

The conventional wisdom was that these types of problems reflected some form of ���pure��� problem-solving ability that reflected a higher type of mental process. The meaning of ���higher��� in this context was never completely unpacked; it was part of a package of beliefs about civilisation, culture and intelligence that were widely accepted as self-evidently true, with the only debate being about details of the definitions.

These beliefs were increasingly challenged by radical freethinkers, from a sociological and political perspective. The ensuing culture wars have far-reaching implications for education policy, with heated debate raging about a wide variety of beliefs and assumptions.

Most people working in education are very much aware of those debates. However, very few people in education are aware of a different set of challenges to the traditional assumptions about problem-solving. Those challenges came from Artificial Intelligence (AI).

AI and problem solving

A key feature of AI is that it involves building software to do things. Building and doing things are both hard, unforgiving tests of a theory. They force you to think through everything involved, with no scope for slips of memory or unfounded assumptions. The results are often very unexpected.

A major case of unexpected results occurred in 1959, when Simon, Shaw and Newell tested their General Problem Solver software. It was intended to do what the name says, namely to solve problems in general, as opposed to specific problems such as the Tower of Hanoi. The core assumption was that using systematic, rigorous logic would allow the software to solve problems at least as well as humans could. That didn���t happen. The reasons gave AI researchers a powerful new set of insights into the nature of real, non-trivial problems, and into ways of tackling those problems. AI systems are now routinely used to handle a wide variety of real-world problems, ranging from assessing loan applications in banks to scheduling ship unloading in major ports.

With regard to problem solving, ironically, AI researchers found that formal logical problems such as the hole-digging problem and the Tower of Hanoi are actually computationally simple. The fact that most humans were bad at solving these problems wasn���t due to the problems being inherently difficult; those problems were actually inherently easy. They involved small numbers of entities, small numbers of rules, and small numbers of possibilities that the software needed to explore.

The large body of AI research since that early study has produced much the same type of findings, and has produced a much clearer understanding of the apparent paradox. Human beings are, ironically, pretty good at solving real-world problems, such as physically digging a hole in the ground with pick and shovel, which are extremely difficult computationally. Human beings are usually very bad at solving computationally simple “two men digging a hole” problems, probably because the human brain hardly ever encountered them during the course of its evolution, so it had no need to develop that specialist set of infrastructure.

The next section examines the differences between these two types of problem.

Constrained problems and real-world problems

In most respects, the constrained (i.e. limited and deliberately simple) problems used in maths exercises and in a lot of problem-solving workshops are diametrically opposite to real-world problems. Some of those differences are as follows.

Known, correct solution or not

Constrained problems typically have a single, known, correct solution. Most real-world problems don���t. Often, real-world problems have more than one solution, or have solutions that are good enough, as opposed to correct. With many real-world problems, it���s impossible to tell whether or not there is a solution.

Search space

When you���re dealing with constrained problems, it���s often possible to work out all of the possible outcomes, and to search through those for the route to the solution that you want. With real-world problems, though, the number of possible outcomes is often too vast to be worked out, so you can���t search through them all.

Algorithms versus heuristics

With constrained problems, there���s usually a method which is guaranteed to give you the answer, if you apply it consistently; this is known as an algorithm. With real-world problems, on the other hand, there usually isn���t an algorithm which is guaranteed to find the answer. Instead, you have to use rules of thumb (known as heuristics) which improve your chances of finding a solution if there is a solution to be found, but which don���t guarantee that you���ll find one.

Perfect, complete knowledge versus the real world

Most constrained problems involve a complete set of accurate and reliable set of starting information, such as how big a hole two men can dig in three days. Most real-world problems don���t have this luxury. Instead, you often have to deal with incomplete information, inaccurate information, probabilistic information and/or unreliable information.

Traditional formal logic isn���t much use when dealing with this sort of messy, horrible information; instead, you have to use heuristics and various forms of specialised logic which give you answers that have a specified likelihood of being correct, as opposed to being definitely correct.

Conclusion

So, where does that leave us?

The short version is that the term ���problem solving��� is being used to refer to two utterly different concepts, with most people being unaware of the profound differences between the two concepts.

This is a classic starting point for confusion, apparently contradictory evidence, and acrimony.

However, if we make this distinction explicit, and build it in to an education framework, then we can distinguish clearly between these two types of problem solving, and can make the correct choices about which type to teach in which places in a curriculum, and about how to assess the two types.

I hope that this article is helpful, and that it will help with the move towards a more evidence-based approach to education.

Notes and links

The painting in the left part of the banner is from Wikimedia Commons:

You���re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they���re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

February 27, 2015

Content analysis: An introduction

By Gordon Rugg

I have very mixed feelings about content analysis. At its best, it gives you a new understanding of the world around you. At its worst, which I see all too often, it���s little more than an attempt to salvage mangled fragments of something useful from the wreckage of a questionnaire perpetrated by some sinner who deserves to be locked in a cell for a while with the assorted works of Barbara Cartland being read aloud over the intercom. Accompanied by accordion music.

So what is content analysis, and why do I have such strongly mixed feelings about it? In essence, it���s about analysing the content of texts. The texts may be questionnaire answers or interview answers, or magazine articles, or books, or online forum debates, or just about anything else that���s spoken or written.

Content analysis is usually something that you ���grapple with��� rather than ���do��� because it���s a messy, nasty problem. The core dilemna is that the further you get from the original words in the text, the more you risk distorting their meaning; however, the nearer you get to the original words, the less sense you can make of what those words are telling you.

There are various ways of tackling this problem, but none of them provide a perfect solution. The result is that there are numerous types of content analysis, which vary widely in their assumptions, methods, strengths and weaknesses. This article describes a ���vanilla flavour��� type of content analysis, which is enough for the needs of many students. I���ll look at other types in future articles.

Vanilla flavour: Counting and categorising significant terms

One widely used form of content analysis, which I���ve described for convenience as vanilla flavour, involves counting how often particular terms occur in the text.

The text may take various forms.

Questionnaire and interview answers

Content analysis is often used on the answers to open questions in questionnaires and interviews, where the participants are asked to answer in their own words, rather than choosing from a specified set of possible answers.

This is one of the many points where the perpetrators of badly designed questionnaires discover that questionnaire design isn���t as easy as it looks, and that questionnaires really do have significant limitations. If you���re designing a questionnaire, it���s highly advisable to do some trial runs with it, including analysis of the data from the trial runs, before starting the main data collection. Analysing the trial data will probably identify a lot of places where re-wording the original questions will produce richer, clearer results that are much less likely to be mangled in the analysis.

Transcripts and recordings

Sometimes the text is a transcript, such as a transcript of a think-aloud session or of an interview or of evidence given in court. Transcripts are invaluable because they provide machine-readable text which is easier to analyse, but they also have various limitations. A low-level problem is that the original wording may be inaudible in places. Another is that if you get someone else to do the transcribing for you, they often ���tidy it up��� by changing the original wording to make it ���more grammatical��� or to remove swearwords. Those are often the most useful parts, which is why “tidying them up” by removing them or changing them is a very bad idea. It���s a good policy to do your own transcribing, but that���s a slow process; the usual rule of thumb is that it takes ten hours of transcription per hour of audio recording. If you���re going to deal with substantial amounts of material, it���s a good idea to teach yourself to do touch typing (i.e. ten finger rather than two finger typing).

It���s also possible to do the content analysis directly off the recording, without transcribing it. This is faster, but has various limitations ��� for instance, there are types of analysis that you can do on a written transcript that you can���t do on the original audio recording, such as the Search Visualiser analyses described below.

Pre-existing documents

A lot of research in media studies and sociology involves analysis of existing documents such as books, magazine articles, film scripts and Internet sources. Often, this analysis looks for significant absences, such as the non-occurrence of minority social groups as protagonists in action movies. The issue of absences is an important one, to which I return later in this article.

The process

The usual core process within vanilla flavour content analysis is to identify key phrases or text fragments, and then to count how often each of them occurs.

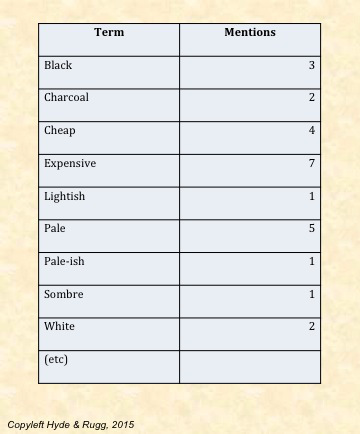

For instance, if you���re researching people���s perceptions of some products, you might list the adjectives and adjectival phrases that people use to describe them, and record how often each descriptive term is mentioned. The result is a list looking something like this. I���ve kept it short for clarity. In practice, the list is usually much longer, and the sheer length of the list can cause a lot of practical problems.

Alphabetical list of terms mentioned

Listing the terms alphabetically has the advantage that it���s easy to do in a spreadsheet such as Excel. Also, you can then easily add together the number of times each term is mentioned.

However, this doesn���t give you much idea of what���s going on within the data in terms of broader categories. To make more sense of it, you need to do further analysis.

One thing you can do, by way of further analysis, is to clump those terms into bigger groups. For instance, ���pale��� and ���pale-ish��� could be combined together in some way. You can do this yourself, or you can ask someone else to do it, to reduce the risk of subconsciously biasing the analysis in the direction that you would like. This person is usually known as an independent judge. In student projects, this is often a friend who does this as a favour, often in exchange for you helping with their project in some way.

The problem with combining terms together is that it can end up as a very messy process; just how do you decide which terms should be combined together, and how many levels of grouping should you use?

Here���s one way of doing the grouping more systematically. It���s the way that Marian Petre and I describe in our book on research methods; it���s based on a standard approach within the card sorts literature.

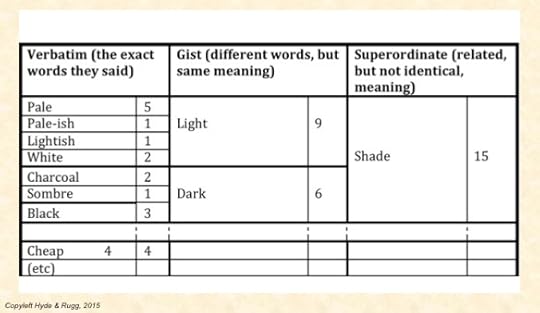

First step: You start by listing and counting the exact words that the participants used. This is the verbatim (i.e. precise words) column in the table below.

It���s important to be strict about only counting identical phrasings together. Note that, for instance, ���pale��� and ���pale-ish��� are listed separately from each other in the list above. This is important because in many fields there are technical terms that look very similar, but that have very different meanings (e.g. ���sulphide��� and ���sulphite��� in chemistry). For this first stage, you shouldn���t make any assumptions about which words might mean the same thing as each other. In fact, it���s perfectly possible that different participants mean different things by the same word, so even the verbatim lumping needs to be viewed with caution.

Second step: You can now lump some of those words together into broader categories, if they mean roughly the same thing. For instance, ���pale��� and ���lightish��� usually mean pretty much the same thing. This is the gist (i.e. same meaning) column below. For the gist column, you total together the numbers from the verbatim words that are being aggregated together within the category (so 5 mentions of ���pale��� plus 1 mention each of ���pale-ish��� and ���lightish��� plus 2 of ���white��� make a total of 9).

We now have 9 gist mentions of ���light��� and 6 gist mentions of ���dark���.

The terms ���light��� and ���dark��� have opposite meanings, but they���re related, in that they both relate to shade. What we can now do is to aggregate these two gist terms together in the superordinate category of ���shade��� and sum their numbers, giving us a total of 15.

We can now go on to do the same for other things that were mentioned, such as cost.

How do you decide which gist and superordinate categories to use? There are various ways, including:

What you think they should be

What an independent judge thinks they should be

What a thesaurus says they should be

Categories used in the previous literature

That���s a swift overview of one version of vanilla flavour content analysis.

So what?

At the end of all this, you may be wondering what the point was. You have a batch of numbers, but what do they actually tell you?

It���s a fair question. For a lot of badly-designed questionnaires, the answer is that the numbers tell you nothing that���s of any use to anyone. This is why my heart sinks whenever a student tells me that they���re planning to do a questionnaire. Good questionnaires are invaluable, but they���re rare; most questionnaires are hacked together by people who are either unaware of the complexities involved in good questionnaire design, or who don���t care about getting it right.

However, when the data collection is done reasonably well, you can do some interesting, useful things with the numbers that you get from content analysis.

For instance, various researchers have pointed out that many of the heroes in adventure stories across various media don���t have mothers. Here���s an example.

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/07/why-are-all-the-cartoon-mothers-dead/372270/

Content analysis lets you see whether this is a real effect or just someone cherry-picking a handful of unrepresentative examples.

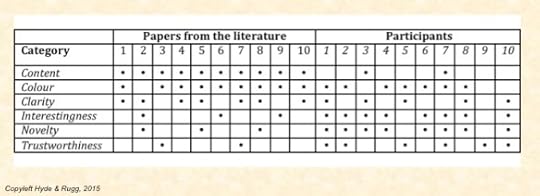

One common recipe for making use of the data is to compare the numbers from the published literature with the numbers from your own data collection. Here���s a hypothetical example, involving perceptions of the key features of a good website.

The first batch of ten columns are papers from the literature, and the second ten columns are your ten research participants; each row represents one of the categories that you used in your content analysis. (I���ve kept the numbers low for clarity and brevity; in reality, you���d be using more papers and/or more participants.) I���ve shown participant numbers in italics, for clarity of explanation.

A black circle in a cell shows that the category in question is mentioned by the relevant paper or participant. This is the simplest form of notation, a binary ���mentioned/not mentioned��� division; you can show other things in the cells instead, such as how often each category is mentioned. I���ve used the binary version for simplicity of explanation.

This format lets you see at a glance how well the literature corresponds with what you found.

For instance, all the papers from the literature in this sample mentioned content, but only two of the participants mentioned content. That���s an interesting difference. Conversely, most of the participants mentioned interestingness, novelty and trustworthiness, but only a few of the papers from the literature mentioned these categories. Overall, this table suggests that there���s a considerable mis-match between what the literature is mentioning and what the participants are mentioning.

We can see other patterns within this table. For instance, among the human participants, every participant who mentioned interestingness also mentioned novelty. Does this mean that the participants are treating the two concepts as synonyms, or do they think that one of those concepts always involves the other? That would be a clear candidate for some follow-up research. Another striking feature is participant 9, who only mentions trustworthiness; was this someone who just didn���t give many answers, or was this someone who had a very different (and potentially very interesting) way of thinking about this topic? Again, follow-up research would be needed to find the answer.

This is a particularly powerful approach when your participants are from a group that hasn���t featured much in the published literature. The vast majority of studies published in journal articles use Western university students as participants, so if you gather data from participants who aren���t Western university students, then you can do a neat, simple compare-and-contrast between your findings and the findings from previous studies.

That still leaves the question of what any differences and similarities mean, which you���d need to explore in a further study, probably using a different method from questionnaires (e.g. observation to find out what���s actually happening, or laddering to find out about values and beliefs). However, the content analysis has provided a solid batch of evidence that can be used as a foundation for that further research, which is a good start.

Advantages

This way of doing content analysis is clear, tidy, simple and completely traceable; the reader can see exactly how you arrived at the numbers you did, at each step of the way. If you���re doing content analysis for your student project, it���s a solid, sensible approach.

Limitations

Content analysis has assorted limitations, which have been the subject of numerous heated debates in the research communities involved. I���ve given a brief summary of various limitations below. Most of these apply to content analysis in general, with different types of content analysis being better in terms of some limitations, but usually at the price of being worse in terms of other limitations.

Practical issues

If you���re working from transcripts, then the sheer time taken to do the transcription can be a problem. Also, getting accurate transcripts is far from easy. If you get someone else to do the transcription, there���s a real risk that they���ll mis-hear or mis-spell crucial words (e.g. specialist or slang terms that they don���t know), and a real risk that they���ll reword the text to make it more grammatical, or to remove swearwords.

Another practical problem is that spoken interactions often involve two or more people talking at once. For some research questions, this can be a key part of the data ��� for instance, if you���re looking at power relations between the speakers, and at who interrupts whom. Transcripts are normally linear, like the written dialogue in a novel, and representing multiple simultaneous speakers is a non-trivial problem. It can be done, but it means that you need to read up on best practice for handling this issue.

Absences

A major issue in content analysis is the things that aren���t mentioned in the text. You���ll need to decide which things to treat as significant absences and which to treat as non-significant absences.

Some absences are because of Taken For Granted (TFG) or Not Worth Mentioning (NWM) assumptions; the person has assumed that those points were so obvious that there was no need to mention them (for instance, the assumption that a product shouldn���t kill a user).

Other absences are because of taboos; for instance, if you did a content analysis of classic 1950s Westerns, you���d find few or no mentions of people going to the toilet.

Some absences are just because of chance; for instance, you happen to select a batch of texts which happen not to include mentions of a topic, although that topic is mentioned in other texts outside your sample. This is particularly likely to happen with topics that are relatively rare; you need to be sure that your sampling process will be able to detect whether mentions of that topic are at about the level that would be expected by chance.

This leads into the deeper, important issues of framing and choice of topics for research. One of the points made by sociologists of science and some of the more constructive postmodernists is that research tends to focus on some areas and to keep clear of others, usually for reasons that involve social norms, politics and religion.

Interpretation and implications

What do the numbers actually mean anyway, and what will you do as a result of knowing them?

This is a key question for any type of research, and it���s one where a proper research design will think about the implications of possible findings right from the start, before the data collection has even begun. There���s not much point in spending a lot of time and effort collecting data if you���re not going to make any use of the answers. For instance, if you���ve used a questionnaire which asks participants whether they���re male or female, are you going to compare and contrast the male and the female results? What will you do if you find that the male results are different from the female results? What will you do if you find that the male results aren���t different from the female results? How much difference counts as ���different��� anyway? If you haven���t worked this out before you start, then there���s a pretty good chance that you���ll end up with a set of findings and with no idea what to do with them. That���s not a good place to be.

In a good research design, you work out in advance what the possible findings could be, and then work out what you will do in response to each of those findings. This is a well established part of standard good practice in research design, but it���s something that amateur questionnaire designers tend to overlook until too late. (Bottom line: If you���re seriously planning to use a questionnaire to collect data, then read up thoroughly on how to do data analysis and research design before you start reading up on questionnaire design. It could save you a lot of time and grief.)

Other types of content analysis

That was a short overview of a widely used, vanilla flavour type of content analysis. It���s far from the only type.

There���s a methodological debate about most things relating to content analysis, which has been running for the best part of a century, and which doesn���t look likely to end any time soon. There are, in consequence, numerous different types of content analysis, and many approaches to content analysis. The following sections give a very brief description of some of those other types. I���m planning to write in more detail about them at some point, when there���s nothing more exciting to do���

Grounded theory is an approach which involves trying to have full traceability from each level of categorisation back to the original data.

This has similarities to laddering, which I prefer for a variety of reasons. If there���s a choice, I prefer to gather information directly via laddering, rather than indirectly via grounded theory analysis of texts.

Laddering is cleaner than grounded theory, with a simple but powerful underlying structure that maps well onto graph theory. Laddering can be used to find out people���s mental categorisation, including how a person���s subjective definitions map on to physical reality.

Cognitive causal maps involve using a subset of graph theory to produce diagrams of the networks of reasoning and evidence used within a text. The classic book by Axelrod and his colleagues contains some excellent examples of how this can be applied to significant areas such as reasoning about international politics by politicians, and of how the results from this approach can be used to predict the future actions of individual decision-makers.

Search Visualizer lets you see thematic structures within a text, such as where and how often women are mentioned as opposed to men, or where hesitation words on an aircraft flight recorder are an indication of a problem arising.

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/06/08/gendered-language-in-shakespeare/

There are more examples on the Search Visualizer blog.

Discourse analysis involves looking at the dynamic aspects of two or more people verbally interacting (whether in a conversation, or a group meeting, or in an email exchange, or in some other medium). This approach can give useful insights into e.g. power structures among the people involved, such as who interrupts whom, and who is able to change the subject being discussed.

Graphs, maps, trees is the title of a fascinating book by Moretti. This brings together a variety of ways of analysing texts, such as showing the spatial distribution of the places mentioned within a novel, or the number of books published within a particular genre over time.

Statistical approaches, including lexicostatistics are useful for fine-grained analysis, and for answering questions such as who might be the author of a particular anonymous work.

Story grammars are powerful formalisms for analysing the plot structures of stories, including books and film scripts. The classic early work was done by Vladimir Propp; his approach is still highly relevant today.

Closing thoughts

Some common criticisms of content analysis are that it:

Involves a lot of effort without much to show for it

Often doesn���t produce anything new or unexpected

Is open to accusations of being subjective

Doesn���t stand up well to ���so what?��� questions

All these criticisms can be true, particularly when the content analysis is being performed on a bad set of data (e.g. the woeful outputs from a poorly designed questionnaire).

Done well, though, content analysis can be very useful. A result that you were expecting may be completely unexpected to other people. For instance, the finding about protagonists who don���t have mothers wouldn���t be much of a surprise to gender theorists, but would probably come as a surprise to most people, and is the sort of unexpected pattern that can make people start thinking about their implicit assumptions about the world.

On which note, I���ll end.

Notes and links

You���re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they���re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There���s more about content analysis and related concepts in my book with Marian Petre on research methods:

Rugg & Petre, A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

February 23, 2015

Life at Uni: Will the world end if I fail my exams?

By Gordon Rugg

The short answer, in case you were in any doubt, is ���No���.

The world won���t end if you fail your exams.

At one level, you already knew that. The planet won���t be destroyed if you don���t get the exam grades you wanted. However, there���s another version of the question that bothers a lot of students. It���s about whether their personal world is going to be destroyed by exam results.

Again, the answer is ���No���. This article is about the reasons for that answer. It���s another gentle, supportive article with practical advice. To set the mood, here���s a picture of a sweet little kitten.

“Wikipedians cat” by Remedios44 – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wikipedians_cat.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Wikipedians_cat.jpg

First, some practical administration: As usual, I���m writing this with my personal hat on, not in my capacity as a Keele member of staff. With that clarified, I���ll return to the topic of this article.

So, there you are, facing exam results in a state of dread. You may have worked yourself to exhaustion, and fallen asleep at the keyboard like the kitten in the picture above, or you may have not worked anywhere near as hard as you think you ought to have worked, or you may have worked sensible hours and still have that feeling of anxiety and fear. You may be trying to ignore that official-looking letter or email with the exam results, or you may be thinking about the looming exams. It���s not a great feeling.

So what can you do to make your life better? There are two main types of things you can do about the immediate situation:

Nuts and bolts solutions (fixing the practical problems)

Chicken soup solutions (helping how you feel)

It���s a good idea to use both nuts and bolts solutions and chicken soup solutions in combination, so that you are improving the situation while also improving how you feel.

Nuts and bolts solutions are about practical steps. They might feel a bit impersonal sometimes, but they improve the situation that you���re in. Here are some examples. I���ve started with things that will give the most immediate help, and moved from there towards longer-term solutions.

Contact the student support services. The staff in student support are usually wise and knowledgeable, and can tell you about practical solutions that you might never have heard of, or never have thought of.

Talk to your tutor. If you don���t want to talk to your tutor for whatever reason, then try a wise, approachable member of staff. They���ll know a lot about options available within your chosen field (for instance, career routes that don���t depend on having a particular class of degree).

Find the support service for exam nerves and anxiety, and sign up. Decide in advance which treats you will reward yourself with after you find the support and after you sign up, and line those treats up in advance so that you get good, positive reinforcement for taking those first steps.

Learn about exam technique. Sometimes a few simple concepts can make a big difference. This is a particularly good idea if you can���t see why you���re not getting better marks; maybe there���s some simple thing that nobody���s ever explained to you. Student support services and/or a friendly member of staff can point you towards your university���s support in this area.

Have a Plan B. It���s a good idea in life always to have an alternative plan, preferably a plan that you can enjoy, as opposed to a dismal ���better than nothing��� plan. This means that you don���t end up with all-or-nothing gambles at key points in your life; instead, you have branch points where both routes are good. That���s a much better situation to be in.

Gather information. Usually there are answers to your questions if you find the right places to look. The student support services and friendly members of staff can usually tell you some good places to start looking. The information may be about exam stress, or exam technique, or about what you can do with your life, or a combination of all of those. I���ll return to this issue later in this article.

Chicken soup solutions are about how you���re feeling, and about ways of helping you emotionally. They might not always fix the underlying problem, but they do help you to feel better. Here are some examples.

Talk to student support services. They���re usually good at helping you get emotional support, as well as practical support. Academic staff will usually encourage you in this direction, so that you can get support from people with training and experience in the specialist area of emotional support.

Set yourself small, manageable goals, with a treat after each goal. This both helps you to feel more in control, and gets you moving again. At the start, ���small��� can be very small; it might be ���getting a small box of chocolates that I can use as rewards���. Take it at a pace that you can manage.

Try the BANJO approach. This works for a lot of people, and it���s well worth a try. It stands for Bang Another Nasty Job Out. It involves doing something unpleasant as your first job of the day, or the afternoon, or whatever time works for you. After that, you don���t set yourself any particularly unpleasant tasks for the rest of the day, as a reward for having done the one you weren���t looking forward to. Remember to choose a job that has a clear end point, so that the rest of your day will be okay.

Have a plan. When you have a plan, temporary obstacles are less intimidating. It doesn���t need to be a great plan, or a plan of what you���ll do for the rest of your life. It might be as simple as ���I���m going to find a reasonably well paid job that involves working outdoors some of the time, and making the world a better place���. That plan doesn���t depend on passing any exams; there are lots of routes to that destination which aren���t affected by exam results. As always, having a Plan B is a useful part of this strategy.

Find and read supportive material. There���s plenty of it around; for instance, books like Feel the fear and do it anyway are excellent both for support and for inspiration.

What next?

Returning to the starting point of this article: Your exam results won���t destroy your personal world. You���ll still have your friends and your family and your health and everything else.

Your exam results can affect your personal plans, but that���s very different from destroying your personal world.

What���s scary about having your plans affected is not knowing what other possibilities are open to you. It���s like the way that horror movies don���t show you the monster in the cupboard, and let your imagination work overtime coming up with all sorts of shapeless dread. The reason they do this is that the reality is nowhere near as scary as what you���re imagining; it���s just someone in a rubber suit, or a segment of computer generated imagery.

It���s the same with life plans. If you re-think the original question as ���How will my plans be affected if I fail my exams?��� then it���s a lot less threatening, and you can start tackling it more effectively. Here���s an example.

Suppose that your plans are based on getting a particular job that requires a 2:I or above, but you get a 2:II. What can you do instead? Some options are:

Go for other jobs that you like and that don���t require a 2:I

Go for a lower-grade entry point in the same career, and work your way up

Do an MSc and then apply for the job you originally wanted

All of these are perfectly feasible, and all of them offer some advantages over the direct 2:I route.

There are a lot of really interesting jobs and careers that most people have never heard of; a few hours spent finding out about them could be the best investment of time that you ever make.

Working your way up within a career can give you a lot more knowledge and credibility than entering higher up, and can display initiative and commitment when you apply for promotion or other jobs.

A lot of MSc courses will accept applicants with a 2:II; getting an MSc might let you apply for the job you originally wanted, and will make you eligible for jobs that weren���t feasible for you previously.

If you fail your exams completely, you probably won���t feel good about it, but again, it���s not the end of your personal world. There are plenty of inspiring, amazing things you can do with your life that don���t need a qualification. The work that I���ve most enjoyed on a day to day level was my time on excavations in archaeology, which didn���t need any qualifications at all.

So, in summary, the main underlying issue is the unknown. Once you start gathering information and making even the most sketchy of plans, everything starts feeling better. Also, the combination of more information and feeling better can create a virtuous cycle, by improving your prospects of getting the results that you wanted in the first place.

I���ll end with another image of a cat sleeping at a keyboard; this time, it���s a cat that���s chosen to sleep beside the keyboard, rather than a cat that���s fallen asleep at the keyboard. It���s an image that has a whole world of positive sub-texts. I hope that it brightens your life, and that it helps you move forward with gentle, happy thoughts.

“Animal testing 1″ by Penyulap. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Animal_testing_1.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Animal_testing_1.jpg

Notes

There���s more about university life in my books with Marian Petre:

The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Unwritten-Rules-Research-Study-Skills/dp/0335237029/ref=dp_ob_image_bk

Rugg & Petre, A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

Related articles that you might find useful:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/18/life-at-uni-after-uni/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/05/life-at-uni-exams/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/12/11/misperceptions-of-failure/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/12/26/why-is-scientific-writing-so-boring/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/06/20/are-writing-skills-transferable/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/07/whats-it-like-at-uni-the-people/

There are a lot of other articles on this site about academic life and education, including topics that students often have trouble with, such as the differences between academic writing and other types of writing. They���re tagged under ���education��� and/or ���craft skills���. You can find others by searching within the site for words like ���writing���. We hope you���ll find them useful; if you���d like to see more on some particular topic, let us know via the comments section, and we���ll see what we can do.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

February 15, 2015

How much is too much?

By Gordon Rugg

There are various well-established answers to the question of how much is too much. (Though being well-established doesn���t necessarily mean that they���re true���)

In this article, I���ll look briefly at four types of answer:

Moral outrage

An unforeseen price

To infinity and beyond

The statistics of uncanny valleys

I���ll look at the statistical type in most detail, because it���s received least attention in the past, and because it has some fascinating implications for fashion, the media, and inter-group relations.

This is a story that goes in some improbable-sounding directions. It starts with mediaeval pointy shoes, lust-crazed beetles, and beer bottles.

Images from Wikipedia; full details and acknowledgements at the end of this article

Images from Wikipedia; full details and acknowledgements at the end of this article

Moral outrage

Traditional answers tend to be based on the opinion of someone with status. Those opinions may be decorated with lengthy philosophical or moral arguments, but in the end, they���re just an opinion, and often they give the impression that the person involved was a grumpy old man who was fed up with seeing anyone else having fun.

Here are some examples of sumptuary laws, i.e. laws that specify how much is too much, just in case you���re wondering whether I���m exaggerating.

���No free woman should be allowed any more than one maid to follow her, unless she was drunk.��� From Wikipedia.

���Only the highest nobility (those of the gong and hou ranks) and the officials of the top three ranks were allowed to have a memorial stele installed on top of a stone tortoise.��� From Wikipedia.

���The length of … the points on mens’ shoes was strictly regulated to distinguish between nobility and common men- 2 �� times the length of the foot for dukes, 1 �� times for nights, and �� the length for common men.��� From digitalbard.

���Peasants ��� could only own one pair of leather boots.��� From digitalbard.

It���s easy to make fun of sumptuary laws, but if you look at the context in which they arose, then you soon spot regularities. One common reason for sumptuary laws is to keep clear boundaries between social classes. The ethics of this are debatable, but the rationale is clear; the laws weren���t simply reactionary attempts to stop people having fun. Instead, they were part of a bigger set of issues.

Another reason involves economics. In classical Roman society, there were serious concerns at one point about the amount of silver leaving the Roman economy to pay for luxury silks from the East. That silver could have been used to pay for things which would help the Roman economy, such as public works, rather than paying for ephemeral display. Elizabethan sumptuary laws had similar reasons behind them; Elizabeth was very much aware of just how little spare money was available within the economy of her country.

This leads on to the next way of judging how much is too much, namely the implications that arise from having something.

An unforeseen price

Advertisements about the good life are usually set in luxurious surroundings, such as gorgeous mansions. One of the clich��s about winning the lottery is being able to buy a mansion or a castle.

That���s understandable; some of those buildings are gorgeous by just about anyone���s standards. Here���s an example of an English country house. A lot of people would view it as a dream home.

Cropped from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Compton_Place,_Eastbourne_%28Geograph_Image_1278100%29.jpg

Cropped from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Compton_Place,_Eastbourne_%28Geograph_Image_1278100%29.jpg

As you might suspect, though, the reality is somewhat different.

One useful way of working out what you really want from life is to imagine that you have what you initially want, and then to think through the consequences. Some exaggeration can help to identify the key issues. Here���s an example.

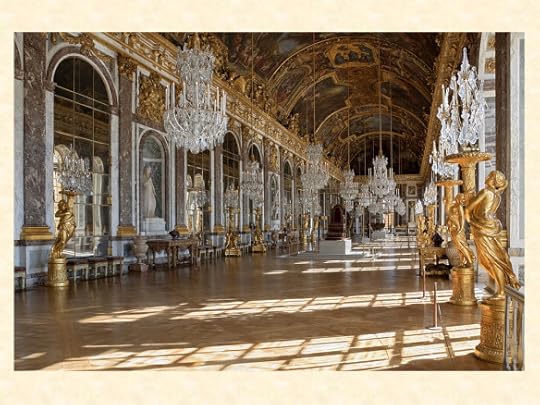

Imagine that you have a chateau in France, with stunning rooms like this one. As a statement of wealth, power and taste, it takes some beating.

“Chateau Versailles Galerie des Glaces” by Photo: Myrabella / Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chateau_Versailles_Galerie_des_Glaces.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Chateau_Versailles_Galerie_des_Glaces.jpg

“Chateau Versailles Galerie des Glaces” by Photo: Myrabella / Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chateau_Versailles_Galerie_des_Glaces.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Chateau_Versailles_Galerie_des_Glaces.jpg

When you stop and think through the practical implications, though, you start to realise that maybe you wouldn���t be so keen on owning it after all. For instance, how would you make sure that the mirrors and chandeliers stay shiny and glittering? There aren���t enough hours in the day for one person to do the upkeep on that room. To maintain that room, and the building, and the grounds, you���d need a substantial number of cleaning, maintenance and gardening staff. Finding and managing staff isn���t exactly a restful pastime; just ask anyone who���s ever dealt with personnel. When you think of it from this perspective, there���s a lot to be said for a home that���s comfortably within the scope of what you can look after yourself.

So, sometimes a good thing comes with a hidden price tag that you wouldn���t want to pay.

To infinity and beyond

Sometimes, though, there isn���t a hidden price tag, and then you can try a very different view of excess, namely that you can never have too much of a good thing. A classic example is the advice that you can never be too rich, or too thin, or have too much chocolate.

There���s a literature on this, in the field of animal behaviour. That literature contains numerous examples of animals favouring objects of desire that are unnaturally exaggerated. These objects are variously known as supernormal stimuli or superstimuli.

An example of superstimuli that appeared in the news recently was a study of mating behaviour in a particular species of jewel beetle. The females of this species are brown and shiny. When male beetles of this species discovered discarded beer bottles which were brown and shiny, and massively larger than the female beetles, they viewed the bottles as the epitome of sexual attractiveness, and proceeded to mate vigorously with them in preference to the female beetles.

The researchers who carried out this study won an Ignobel Prize (a humorous award for research that cannot, or should not, be replicated) and received a lot of humorous attention in the media.

Behind this study, though, there���s a serious point. With superstimuli, there doesn���t seem to be an obvious upper limit. In the case of the male jewel beetles, the beer bottles were several times longer than the female beetles, and hundreds of times bigger in volume than the females. The males didn���t treat this as evidence that the bottles might not be females; instead, they persisted in mating with the bottles until they died of exhaustion.

In an earlier article, I described a very interesting paper about aesthetics by Ramachandran and Hirstein. That paper implied that there wasn���t an upper limit to superstimuli. However, there are indications scattered through the research into aesthetics that there may be another factor involved. This takes us into a finer-grained and more nuanced set of issues.

The statistics of uncanny valleys

I���ll start with a well-established phenomenon that���s entered popular culture in recent years, namely the uncanny valley.

The Japanese robotics researcher Masahiro Mori noticed that if you make a robot more human-like, then people tend to like it more, but only up to a certain point. At that point, people start to find the robot creepy, because it���s moved into an unsettling zone where it���s neither definitely a robot nor definitely a human. Once it���s moved beyond that zone, the robot should start to become more attractive again (for instance, the cyborg Seven of Nine in Star Trek Voyager and the replicants in Blade Runner).

Images from Wikipedia; full details and acknowledgements in the notes at the end of this article

Images from Wikipedia; full details and acknowledgements in the notes at the end of this article

Conversely, human beings can stray into the uncanny valley by routes such as plastic surgery, cosmetics and PhotoShop, which make the person look too smooth-skinned and blemish-free to be clearly human.

Mori argued persuasively that many of the things we find unsettling and scary are in that uncanny valley, neither definitely human nor definitely non-human; for instance, dead bodies, badly injured people, and assorted monsters from fiction such as zombies, vampires and werewolves.

It���s a plausible argument. It also ties in with other features of human cognition. I���ve argued in this blog and in my book Blind Spot that the uncanny valley is likely to be related to broader issues, such as Necker shifts between two or more different interpretations of a scene.

The uncanny valley phenomenon raises questions about whether human aesthetic preferences are invariably a simple ���more is better��� effect, or whether something else might be going on in at least some places.

When you start digging around in the literature, you find some interesting evidence pointing towards the existence of an upper limit to ���more is better���.

One example is height. There���s a solid body of research showing that height in males is positively correlated with assorted measures of social status and success, including salary. However, this tendency only works up to a certain point. In studies conducted in North America, that point is a height of somewhere between six feet and six feet two inches. Up to that height, the taller you are, the higher your salary is. Beyond that height, the effect fades away, except for a handful of cases such as basketball players where greater height has functional advantages.

There���s a similar effect for the ratio between leg length and body length in women, where longer legs relative to overall body length are perceived as more attractive, but only up to a point. There appears to be a similar effect for bust size in women, where women with very large, cosmetically enlarged busts tend to be portrayed in the media as freaks, rather than as hyper-attractive because of a superstimulus effect.

This is a difficult area to research rigorously because of a wide range of confounded variables, including a whole tangle of gender issues associated with the majority of studies (for instance, the tendency to focus on sexual attractiveness of women to heterosexual men). However, it looks as if there���s a regularity within those studies which find that more isn���t always better.

The regularity seems to be that the ���up to a point��� figure is between one and two standard deviations from the mean average. What this translates to in lay language is that if you rank a hundred randomly selected people from shortest to tallest, then the tallest five or thereabouts will be perceived as having the greatest status, but the very tallest person will probably be perceived as being ���too tall��� or ���freakishly tall���. The same would go for leg to body length ratio, and so on. In non-mathematical terms, it means that ���tall��� is attractive, but ���very tall��� is not attractive.

The obvious assumption is that very tall people are moving into an uncanny valley, and starting to be perceived less favourably as a result. A further implication from these studies is that increasing height will move those people deeper and deeper into the uncanny valley, with no prospect of emerging from it at the other side. In this case, a better metaphor might be the uncanny cave.

Discussion

So what, if anything, is going on here, and what are the implications?

To start with, there���s a widespread dynamic in nature that involves having more of a desirable attribute. There���s a solid literature about this, covering topics such as competition for mates and for resources.

That literature also describes another widespread effect, namely that having more of an attribute may be good in one way, but may bring a cost in another way. A common pattern is that being physically bigger is better in terms of being more attractive to potential mates, but also more risky because it also increases the risk of attracting hungry predators.

From the literature on superstimuli, it appears that generally there doesn���t seem to be a point at which ���more��� becomes ���too much��� for aesthetic reasons (as opposed to becoming e.g. ���too risky��� because of a separate set of reasons, and also as opposed to addiction, which is a complex, separate issue).

From the literature on human aesthetic preferences, however, it looks as if there is sometimes a point at which ���more��� does become ���too much���. There���s some evidence that this point is about one or two standard deviations from the average value (e.g. ���tall��� is attractive as opposed to ���very tall��� which is starting to move into the uncanny valley).

I think that this aspect of the statistics of aesthetic preferences could be a rich field to investigate, because it ties in with a well-established body of research in psychophysics. That body of work dates back over a century, and it has done an impressive job of uncovering how human perception maps onto the physical properties of stimuli.

One example of this is the concept of the Just Noticeable Difference (JND). If you ask people to judge which of two weights is heavier, for instance, then you can start plotting regularities in which differences people can or can���t perceive, across a wide range of absolute values.

When Fechner investigated this in the nineteenth century, he found that there was a non-linear relationship between perceived differences and actual measured differences in stimuli. It���s a big, fascinating area with a lot of far-reaching practical implications.

A further speculation is that the ���distance from the average��� model provides a possible explanation for something that sales people know all too well. It���s the customer who spends ages trying to choose something very tightly defined (e.g. ���I want to buy a traditional nineteenth century town house with period features���) and who then buys something completely different, such as an ultramodern apartment.

Sometimes this happens because the client is initially window-shopping for their fantasy purchase (e.g. the glossy sports car) but then settles down to the mundane business of buying what they actually need (e.g. the sensible family saloon). Other times, though, window-shopping clearly isn���t the explanation; the client is explicitly looking for their dream purchase, and is able to afford it.

What might be happening in such cases is that the client is looking for something that���s a particular distance from the average in one direction and then, when they can���t find anything suitable there, they look the same distance in the opposite direction from the average, and find something at that point.

It���s a speculation, but it makes sense, and it ties in with a lot of established findings from various fields.

Conclusions and further thoughts

It���s obvious that different people have different world views in terms of what they desire.

Some people want as much of something as possible; ultra-rich traders, for instance, who keep amassing more money even when they already have billions.

Often, though, people have limits to their desires. Often, the reasons for those limits are practical ones (the ���who will clean the mirrors?��� factor). However, there���s also evidence suggesting that some of those limits form a statistical pattern, one or two standard deviations from the average.

This issue has a lot of practical implications for any sector which involves trends in customer preferences. That description covers a huge number of sectors, from music and the media to houses, cars and fashion.

A common phenomenon within those fields is what���s known in game theory as an arms race, where manufacturers compete on one feature, such as the number of features on a mobile phone. Usually what happens is that the feature ends up being increasingly exaggerated until it becomes silly, at which point everyone stops bothering about that feature, and the competition shifts to a new type of feature. A classic example is the big American classic car with huge tail fins, which was suddenly abandoned in favour of small, sensible town cars packed with neat design features.

This sort of arms race may look silly from the outside, but it���s deadly serious to the manufacturers, who have to stay in the game, but who can���t be sure about when the bubble will burst, and leave them stranded with a product that���s become outdated overnight.

When you start looking at these competitions in terms of psychophysics and of statistical distance from the average prototypical schema for a product, though, you have a way of looking for regularities in when the bubbles burst. Will there actually be regularities that manufacturers can use? I don���t know, but it would be fairly easy to find out, and it would make life a lot more manageable for everyone involved.

Finally, thinking about how much is too much is useful for working out what you really want out of life.

The question about who will do the cleaning might sound like a way of dampening someone���s dreams, but in fact it can be liberating. If you realise that what you want is the experience of living in a castle, as opposed to owning a castle, then your dream becomes much more likely to happen. Many castles have been turned into hotels. Staying for a while in a castle-turned-hotel involves far less cost than buying a castle, so you could spend many happy years fulfilling your dreams by holidaying in castles around the world.

On which inspirational note, I���ll end for now. I���ll revisit the issues above, and a variety of related issues, in later articles.

Notes

Banner image sources:

“Arsen 5104 f14 detail2″ by http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/ARTH/arth214_folder/burgundy_intro.html. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arsen_5104_f14_detail2.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Arsen_5104_f14_detail2.jpg

“Buprestidae – Julodimorpha bakewelli” by Hectonichus – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buprestidae_-_Julodimorpha_bakewelli.JPG#mediaviewer/File:Buprestidae_-_Julodimorpha_bakewelli.JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beer_bottle#Stubby_and_steinie

“VB-stubbie”. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VB-stubbie.jpg#mediaviewer/File:VB-stubbie.jpg

Uncanny valley image sources:

“Borg Queen 2372″. Via Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Borg_Queen_2372.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Borg_Queen_2372.jpg

“SevenofNine” by Source (WP:NFCC#4). Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SevenofNine.jpg#mediaviewer/File:SevenofNine.jpg

“Tears In Rain Roy” by Source. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tears_In_Rain_Roy.png#mediaviewer/File:Tears_In_Rain_Roy.png

February 8, 2015

A cheering tale: The Gimli Glider

I like the story of the Gimli Glider. It���s a feel-good true story, for days when a person needs a feel-good true story; it���s invaluable as a case study for my students; it���s also good for putting problems into perspective on a hard day.

If the name gives you surreal images of a Middle-Earth dwarf wielding an axe in a sailplane, you might be relieved to learn that the reality is very different, though equally surreal in some ways.

It���s the true story of an airliner that ran out of fuel at 41,000 feet, because of a misunderstanding about whether it had been fuelled in litres or in pounds of fuel. At that point, it became the world���s largest glider. The co-pilot recommended an emergency landing at Gimli airfield, which he knew from his days in the Royal Canadian Air Force. The pilot landed successfully, largely because he happened to know a lot about flying gliders. Nobody died; everyone walked away, with feelings of disbelief and massive relief. Even by the standards of movies about fictional aircraft in jeopardy, it���s quite a story.

Images from Wikipedia; details with attributions at the end of this article

Images from Wikipedia; details with attributions at the end of this article

So how do you manage to run out of fuel at 41,000 feet? It���s a classic example of what���s known as a normal accident. In 1983, when this happened, transition from Imperial to metric units was a live issue. To anyone familiar with complex systems and human factors, it was a disaster waiting to happen. Sooner or later, someone would use the wrong units, and something would go horribly wrong. That doesn���t mean that the decision to make the change was wrong; usually in life, there isn���t a completely risk-free option, which is why professionals in the field think in terms of risk management and risk reduction rather than risk elimination.

Refuelling an aircraft is a very different proposition from refuelling a car. One big difference is that you deliberately don���t fill the fuel tanks up completely unless you really have to. This is because fuel is heavy, and you don���t want to haul more weight through the sky than you have to. When you���re refuelling an aircraft, you work out how much fuel you���ll need for your flight, and then put in that much plus a bit extra as a safety margin, to keep the weight down. That process has quite a lot of room for error, which is why there are numerous checkpoints in the procedure to reduce the risk of those errors. When Air Canada Flight 143 was being refuelled, the procedures for refuelling had recently been changed. On top of that, there were some mechanical problems with the fuel monitoring system, and to round things off, one of the people involved was distracted part-way through the procedure. The pilots double-checked the figures, but because some of the numbers they had been given were inaccurate, the double-checked results were wrong. So, in summary, nobody was silly, everybody was conscientious and sensible, but a whole batch of individually minor problems all happened at the same time, so the error slipped through.

The odds of that string of events happening are pretty slim, but when you���re looking at a field like aviation, where there are very large numbers of flights every day, then slim odds come up more often than anyone would like.

The Wikipedia article gives a good description of the events. There���s also a feel-good movie which is worth watching, plus at least one documentary.

In brief, the engines ran out of fuel about half-way through the flight. The First Officer, Maurice Quintal, suggested that they land at the Gimli airfield in Manitoba. Captain Bob Pearson managed to land the plane safely, despite the fact that the runway involved had been decommissioned and was being used for a sports car race at the time of the landing. The two pilots were initially reprimanded and punished, on the grounds that running out of fuel in mid air wasn���t something that aviation authorities approve of. Soon afterwards, when several other crews had tried to pull off the same landing in flight simulators and had all crashed, Pearson and Quintal were given medals, on the grounds that landing safely was something that aviation authorities strongly approve of. The full story is even more colourful and improbable (including the part about the three children on bicycles at the end of the runway who were unaware that they were being followed by a landing airliner, because it wasn���t producing any engine noise).

The feel-good aspect of the Gimli Glider story is easy to describe. Human beings face a life or death challenge, and rise to that challenge; everyone plays their part, and the story ends happily for everyone involved. One of the striking features of the movie based on this story is that there���s only one token obnoxious passenger, and you get the impression that he was inserted by the scriptwriters because they didn���t think that anyone would believe the script otherwise. (On the other hand, it was an Air Canada flight, so maybe audiences would have happily accepted that the passengers would feel culturally obliged to be quietly, politely heroic and can-do���)

In terms of a case study, it has a lot going for it.

For starters, there���s the consideration that nobody died or was seriously injured. That���s a huge plus. Most case studies about safety-critical systems involve something going bang, followed by people dying. There���s a lot of human tragedy in safety-critical systems studies. You don���t want to traumatise students by getting into the grisly details of cases where people died horribly, so a case where everyone walked safely away is very welcome.

Another issue is that if you���re going to work in that field, with the aim of preventing future tragedies, then you need a coping strategy so that you remain able to function. Two common strategies are to develop a dark sense of humour, and to treat the cases as intellectual challenges. Both these strategies can fend off burnout and emotional breakdown for quite a while, but they can both be seriously misunderstood by people outside the field, since they can both look like not caring or not taking human life seriously. Again, the Gimli Glider works well as a case study, since there are quite a few moments of dark humour in the story, but because there’s a happy ending, this is easier for people to handle. The humour in this case isn���t a coincidence. This leads into another reason that I like to use this as a case study.

As I���ve mentioned in a previous article, a major feature of humour is that the same situation can be explained in two very different ways. That���s what happened with the refuelling of the Gimli Glider. There was a sequence of misunderstandings, all of which made complete sense in relation to one key assumption (that the aircraft fuel measurements were in kilos). Unfortunately, the refuelling sequence was also a perfect fit with a different key assumption (that the aircraft fuel measurements were in pounds).

The punch line is the place where the audience realise that they���ve been using the wrong mental model for what���s happening, and that they need to switch to a very different model. That���s just what happens when the pilots of the Gimli Glider, and the students hearing the story, realise that the plane had been filled up in Imperial rather than in metric.

If this new model leads to death and injury for real people, then we���re looking at a tragedy in the classical sense. However, this also has the same structure as a joke. Dark humour involves recognising the humour as well as the tragedy, and this can lead to a lot of mental unease among the audience. In the case of the Gimli Glider, there isn���t any death or serious injury, so the students can see the underlying misunderstandings and alternative explanations without the complication of mental unease about the consequences.

There���s a lot more in this case study, about organisational behaviour and systems theory and human factors and numerous other issues. I won���t go into detail here; instead, I���ll move on to the third main reason that I like this story.

The Gimli Glider story is great for putting most worries into perspective. Imagine that you���re on that flight, on your way home, fretting about how to tell your parents that your exam results weren���t what you wanted. How would you and your parents feel about those exam results as you walked away from the aircraft, with the rest of your life ahead of you, and inspirational music bringing in the closing credits?

On which positive note, I���ll end.

Notes and links

Sources of images used in this article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gimli_%28Middle-earth%29

“K21 glider” by Paul Haliday – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:K21_glider.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:K21_glider.jpg#mediaviewer/File:K21_glider.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gimli_Glider#mediaviewer/File:Gimli_glider.JPG

(Used under fair use terms, as part of an article about the research context of the flight.)

January 23, 2015

Exam season mood lifters

By Gordon Rugg

It���s exam season. Academics are feeling blue because they have to do piles of marking. Students are feeling blue because they���re dreading the results of that marking.

It���s a good time for a mood lifter.

Still from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amCeqrpYzes used under fair use principles, as a low-resolution still used for humorous purposes.

Here���s something that should brighten your day without demanding too much mental effort. It���s Japanese idols singing Dschinghis Khan. The song is indeed about the Mongolian leader Genghis Khan, whose name has an impressive number of variant spellings. It had its origins in Eurovision, in 1979, where it was performed by the band Dschingis Khan. I’ll draw a discreet veil over that experience. Anyway, here’s the Japanese idols version.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtFSCvLLluw

If your humour tends towards surrealism, then the Leningrad Cowboys cover of the same song is well worth trying, and has the added bonus of the subtitled lyrics in German (although they aren’t singing in German or their native Finnish, because that would be too easy):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amCeqrpYzes

If your musical tastes tend towards the macabre, then you might like the Leningrad cowboys doing country and western:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CI5erjH1ErA

Yes, this is indeed a Finnish band singing in English with Spanish subtitles.

If this is your first encounter with the Leningrad Cowboys and you���d like to see more, then you might like the film that started them on their way, Leningrad Cowboys go America:

http://www.amazon.com/Leningrad-Cowboys-Go-America/dp/B000026B2G

I hope this has brightened your day.

January 18, 2015

Life at Uni: After uni

By Gordon Rugg

If you���re trying not to think about life after university because it all feels too scary and depressing, then you���re in good company. Most students feel that way sooner or later.

This article is about other ways of looking at life after university, particularly if you���re scared and/or depressed and/or have no idea what to do next. It���s a gentle article. Here���s a picture of some kittens to set the mood.

“4 Kittens” by Pieter Lanser from The Netherlands – IMG_9051Uploaded by oxyman. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:4_Kittens.jpg#mediaviewer/File:4_Kittens.jpg

“4 Kittens” by Pieter Lanser from The Netherlands – IMG_9051Uploaded by oxyman. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:4_Kittens.jpg#mediaviewer/File:4_Kittens.jpg

The kittens in the picture are probably feeling just like you, if you���re a final year student thinking about the future, and wondering just how scary it could be. Anyone who has lived with kittens, or worked with students, knows that look very well.

In the case of kittens, that look will be followed by some cautious exploration, which is usually completely endearing, soon followed by joyful rampaging, with the initial fears long forgotten. It���s much the same with students, except that there���s less likelihood of someone having to retrieve them from the top of the highest bookcase or from inside the sofa.

So, if you���re feeling uneasy about the future, hold on to your mental image of those kittens, and think about how much fun they���ll have when they discover how many things in a house can be used as kitten toys.

That should make you feel a bit better, which is a good start. However, it doesn���t answer any of the questions that are probably niggling away at you in the small hours when you can���t sleep. The next sections deal with some common questions.

What if I can���t find a job?

A useful rule of thumb with difficult questions is to flip them round. One way to flip this question round is to rephrase it as: ���What if I can���t find my dream job as soon as I leave university?���

When you phrase it this way, it gives you a much more manageable perspective. Nobody in their senses would expect to go straight into their dream job from university. Before you get to your dream job, you need to build up the experience and skills to make you ready for it, which means getting jobs that aren���t perfect, but that are good enough as steps along the way.

So, when you think in terms of getting a job as a starting place, that���s a much more manageable prospect. This leads into the next question���

What if I don���t like my job?

One obvious, and usually sensible, option is to move to another job. There are good ways of doing this, and bad ways of doing it.

The underlying theme in the bad ways of changing jobs is being negative. A classic question at job interviews is: ���Why did you leave your last job?��� If your reply is a string of complaints about it, then you can give the impression of being a chronic complainer who will be no fun to work with. The standard guidelines for job interviews contain plenty of more positive phrasings.

The underlying theme in the good ways of changing jobs is that you get as many positive things as possible out of each job while you���re in it. This includes learning new skills, and taking time to figure out what you���re getting from the job. From this viewpoint, time spent in a hard, demanding job can actually be a very strong point. It improves your chances of getting a less demanding job, because it gives you credibility; it also improves your self-esteem, because you know that you’ve done something hard and emerged successful at the other end.