Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 7

February 26, 2016

Intrinsic, extrinsic, and the magic of association

By Gordon Rugg

As regular readers of this blog will know, I have an awed respect for the ability of Ancient Greek philosophers to spot a really important point, and to then produce an extremely plausible but only partially correct explanation, sending everyone else off in the wrong direction for the next couple of thousand years.

Today’s article is about one of those points, where the Ancient Greeks didn’t actually get anything wrong, but where they laid out a concept that’s only part of the story. It involves a concept that can be very useful for making sense of consumer preferences and life choices, namely the difference between intrinsic properties in the broad sense, and extrinsic properties in the broad sense.

Here’s an example. The image below shows a pair of Zippo lighters. One of them is worth a few dollars; the other is worth tens of thousands of dollars, even though it’s physically indistinguishable from the first one. Why the difference? The answer is below…

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zippo-Lighter_Gold-Dust_w_brass-insert.jpg

In Philip K. Dick’s alternate history novel The Man in the High Castle, Nazi Germany has won World War II. One of the characters in the novel wonders whether history might have taken a different route if Roosevelt hadn’t been assassinated in 1933. He’s prompted to wonder this by the proposed sale of the Zippo lighter that was in Roosevelt’s pocket at the time of the assassination. That lighter is a unique item, worth a small fortune; the character muses about the fact that a physically indistinguishable lighter without that association would be worth only a few dollars.

There’s a useful concept in the card sorts community that handles this issue. It involves distinguishing the observable features that are part of an object from the features that are associated with the object in some way, but are not part of it.

This distinction is very useful if you’re working on the design or requirements for something. It lets you separate the features over which you have some control (e.g. the materials that you use) from the features over which you don’t have any control (e.g. a customer’s past experiences). You can go through the list of features that you’ve elicited from your market research respondents, or whoever is involved, and partition the features fairly cleanly into two sets, then focus on the set of features that you can do something about.

So far, so good.

One obvious question is what to call these two sets. This is where things start to go downhill.

In the card sorts community, the usual terms are intrinsic (for the observable features that are part of the object itself) and extrinsic (for features that are external to the object, and are not part of it in any way that can be observed in the object itself). Intrinsic is a fairly familiar term, and extrinsic is an obvious corresponding concept, even if it’s less familiar to most people.

Unfortunately, those terms have already been taken, by the Ancient Greeks, who used them in subtly different ways. There’s nothing wrong with those subtly different ways; on the contrary, they’re very useful. However, they only handle part of the issue. The ancient distinction is, in brief, between the properties of the material from which something is made, which are the intrinsic properties in this definition, and the properties of an object which was made using that material (the extrinsic properties, in this definition). It’s a useful distinction, but it doesn’t cover the same ground as the distinction made by the card sorts community.

So, there’s a need for a new pair of terms, and I’d be very grateful to anyone who could suggest suitable terms that haven’t already been used in some subtly but profoundly different way. (In case you’re wondering, the term inherent has already been taken by philosophers, again with a sensible meaning that isn’t the same as what I’m talking about here. So it goes, sometimes…)

That’s the background about this pair of concepts, by whatever name you call them. I’ll stick with the card sorts definition for the rest of this article.

Which takes us back to one of the early questions. Why should the extrinsic properties of an object be worth hugely more than the intrinsic properties, even when it’s physically impossible to tell from the object itself what its extrinsic properties are, as in the case of the Zippo lighter that was in Roosevelt’s pocket?

The magic touch…

The answer is probably to be found in the concepts of mana and of magical contagion. These are important concepts in anthropology, and central concepts in marketing, media and politics.

In brief, mana is a Polynesian concept for a sort of spiritual power. It’s not just applied to people; inanimate objects can have it. The concept is widely used in anthropology and in popular culture, and is often applied to non-Polynesian objects. For instance, objects that belonged to famous people can be described as having a lot of mana, as a result of their association with those people.

Magical contagion is a widespread concept, found in various forms around the world. The core concept is that mana can be transferred, so that a person can acquire some mana from ownership of an object. In some belief systems, simply touching the object can transfer mana; in others, mana is transferred via rightful ownership.

It’s tempting to think of these concepts as irrational and superstitious, but they’re another example of identifying a real, important phenomenon, and then coming up with a plausible but horribly misleading explanation.

A lot of the features traditionally associated with mana and with contagion magic make a lot more sense if you re-frame them in terms of concepts such as honest signalling. This is a concept from evolutionary ecology, and it describes ways of sending out signals that cannot easily be faked. Honest costly signals are widely used among animals in situations such as competition for mates, where an honest signal can help you to avoid a potentially disastrous fight against an opponent who is likely to beat you.

How do you know that a signal is actually honest? One common approach is to use costly signals, which cannot easily be faked. Yes, they’re expensive, but that’s the point; they show that you’re in a league where you can afford that expense, and they’re still cheaper than the alternative risk. Peacock tails are a classic example.

Among humans, signals can relate to a range of social currencies, as well as to financial currency. A common social currency is affiliation with a powerful person or group. If a powerful person gives you an object which is a visible signal of their trust or affection, then it’s a signal that you have powerful social support. This is why the giving of rare, high-status objects is a big deal in societies around the world. The objects themselves may be useless in practical terms (for instance, a polar bear as a royal gift is striking to look at, but not a lot of use for anything around the house). In social terms, though, they are very useful, because they’re an honest, costly signal of your status, and of your access to goods and resources that most people don’t have.

So, in summary, extrinsic features such as who gave you an object can have very real practical implications. Often, though, they are easy to fake, which is why having a solidly-established body of evidence for the provenance of the object is a huge deal in the world of antiques and collectables.

On which note, I’ll end.

Links and notes

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

You might also find our website useful for an overview of our work.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

January 24, 2016

Things, concepts and words

By Gordon Rugg

There’s a useful three way distinction in linguistics between things, concepts and words.

This article is a gentle examination of the distinction, with some thoughts about implications for human error.

Unicorns and non-unicorns Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

I have a deep, quiet love for linguistics. When I encountered the subject as an undergraduate, it was the first time that I really grasped what science was about. It was clean and elegant and it mapped on to reality in a way that opened up a whole new way of looking at the world.

One of the first things you learned on a linguistics course back in the day was the distinction between things, concepts and words. It’s simple, but it’s powerful.

Things means what you might expect; real, solid, tangible objects such as horses, or colours, such as grey, or observable actions, such as grazing.

Words are also what you might expect; names, or labels.

Concepts are more complex. They’re abstract mental entities, which don’t necessarily need to correspond with a thing.

Here’s an example.

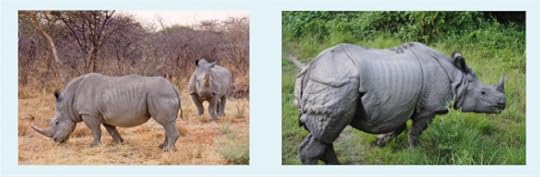

The first image in the banner above is of a thing, which has a corresponding concept and word, namely rhinoceros.

So far, so straightforward. Where this three-way distinction starts to become interesting is when we look at cases like the two below.

Two concepts or one? Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Both these images are of things. Both of them map onto the concept and word rhinoceros. However, there’s no inherent necessity for that to happen. The two animals in the photos are similar in some ways, but very different in others. In English, they are treated as sub-categories of the same core concept. I’ll come back onto the issue of sub-categories at the end of this article.

To clarify the issue involved, here’s another set of images. For most native speakers of English, the three things in the images below map onto three different concepts and words, namely horse, donkey and pony. However, the three things are biologically more similar to each other than the animals lumped together under the single concept rhinoceros – horses, ponies and donkeys are similar enough to be able to inter-breed. Treating them as three different concepts is very much a human, social distinction.

Horse, donkey, pony: Three different concepts Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

In summary, things exist regardless of human preferences; concepts and names, in contrast, are human inventions.

This leads to some interesting situations, such as when a concept and a corresponding word exist, even though no corresponding thing exists. The classic example is the unicorn, where the concept and the word exist, but not, alas, actual unicorns (despite what Caesar had to say on the subject).

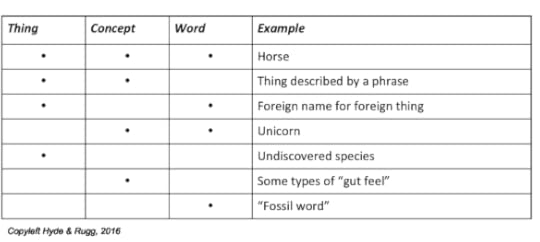

Here’s a table that spells out the permutations, with an example of each.

The first row is straightforward; there’s a tangible object, with a corresponding concept and word.

The second row involves cases where something exists, and you have a concept for it, but you don’t have a simple name for it; usually, instead, you describe it with a phrase, such as “That feeling you get when X happens”.

The third row is all too familiar to anyone trying to learn a language by direct instruction in that language. Someone shows you an object, and tells you what it’s called, but you have no idea what the concept is.

Here’s an example.

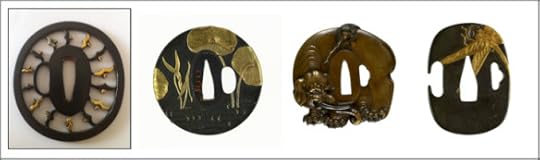

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

Sources for images are given at the end of this article

The object on the left, with the radiating spokes around the central hole, is a tsuba. You now know the thing, and the word. What about the other three objects next to it? Are they tsubas, or not? They look similar in some ways, but very different in others; do they belong within the same concept in the culture where they originate, or are they something very different that just happens to look superficially similar?

Returning to the table: The fourth row is interesting, in terms of the error of reification; there’s a concept and a word, but there’s no corresponding tangible object. A classic example is the unicorn, where the concept is well defined in western culture, and the word is well established. However, that doesn’t, unfortunately, mean that unicorns exist. There’s been a lot of debate about various medical concepts in this regard; just because there’s a concept and a name, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they reflect an actual medical condition (e.g. the medical debate about whether Gerstmann syndrome really exists as a thing in its own right).

The fifth row maps onto, for instance, a newly discovered species that hasn’t yet been named.

The sixth row describes “gut feel” concepts that we can’t put into words, and that don’t actually correspond with reality.

The final row describes something that quite often turns up in historical linguistics, where we can read a word in an ancient text, but we have no idea what the word means, often because it only occurs in one place. This is a significant problem for biblical translators; for example, the biblical story of Noah’s ark says that the ark was made of “gopher wood”. This has nothing to do with the animal called a gopher; instead, it’s a transliteration of a word (“gopher”) which only occurs in that one place, and whose actual meaning has been lost. It’s some kind of wood, or adjective applied to wood, but nobody knows what it means.

Closing thoughts

Although the core distinction between things, concepts and words is simple, it leads into a lot of interesting issues. This article has skimmed the surface of some of those issues. For instance, there’s the question of how to handle cases where we’re not sure whether or not something exists. This was the case for the unicorn in the middle ages, where distinctive spiral ivory horns definitely existed, and helped to differentiate the concept of the unicorn from the concept of the rhinoceros, but where the source of those horns wasn’t definitely known for quite a while.

As for concepts such as the soul, or consciousness, much can be said, and already has been, about whether or not these are concepts and words without any corresponding thing.

There are also related literatures that I’ve left for a later article. I haven’t, for instance, gone into the issue of folk taxonomies, where there’s been some very interesting work by people like Rosch on the “core” levels at which people categorise, as opposed to the sub-type distinctions that are made using modifiers, such as “Javan rhinoceros” as opposed to “black rhinoceros”. Similarly, there’s a large and fascinating body of research into the way that language reflects what a culture cares about.

I’ll be returning to this theme in another later article, looking at how languages handle numbers, and at the implications for how most people handle estimates of probability.

Notes and links

Sources of images:

“Waterberg Nashorn2” by Ikiwaner – Own work. Licensed under GFDL 1.2 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waterberg_Nashorn2.jpg#/media/File:Waterberg_Nashorn2.jpg

“Oftheunicorn” by Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries – http://digital.lib.uh.edu/u?/p15195coll18,33. Licensed under CC0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oftheunicorn.jpg#/media/File:Oftheunicorn.jpg

“Narwhals breach” by Glenn Williams – National Institute of Standards and Technology. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Narwhals_breach.jpg#/media/File:Narwhals_breach.jpg

“One horned Rhino” by Krish Dulal – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:One_horned_Rhino.jpg#/media/File:One_horned_Rhino.jpg

“Grey Icelandic horse” by Soffía Snæland from Njarðvík, Iceland – Hestur. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grey_Icelandic_horse.jpg#/media/File:Grey_Icelandic_horse.jpg

“Alboxmonachilmotril 039” by No machine-readable author provided. Iván Salvía assumed (based on copyright claims). – No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims).. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alboxmonachilmotril_039.jpg#/media/File:Alboxmonachilmotril_039.jpg

“CanadianRusticPony” by SriMesh – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CanadianRusticPony.png#/media/File:CanadianRusticPony.png

“Shakudo Tsuba” by Grizan – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shakudo_Tsuba.jpg#/media/File:Shakudo_Tsuba.jpg

“Japanese – Tsuba with a Frog in a Lotus Pond – Walters 51177 – Back” by Anonymous (Japan) – Walters Art Museum: Home page Info about artwork. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_-_Tsuba_with_a_Frog_in_a_Lotus_Pond_-_Walters_51177_-_Back.jpg#/media/File:Japanese_-_Tsuba_with_a_Frog_in_a_Lotus_Pond_-_Walters_51177_-_Back.jpg

“Tamagawa Masaharu – Tsuba with a Monkey Teasing an Elephant with a Stick – Walters 51281” by Tamagawa Masaharu – Walters Art Museum: Home page Info about artwork. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamagawa_Masaharu_-_Tsuba_with_a_Monkey_Teasing_an_Elephant_with_a_Stick_-_Walters_51281.jpg#/media/File:Tamagawa_Masaharu_-_Tsuba_with_a_Monkey_Teasing_an_Elephant_with_a_Stick_-_Walters_51281.jpg

“Japanese – Tsuba with a Dragonfly – Walters 51254” by Anonymous (Japan) – Walters Art Museum: Home page Info about artwork. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_-_Tsuba_with_a_Dragonfly_-_Walters_51254.jpg#/media/File:Japanese_-_Tsuba_with_a_Dragonfly_-_Walters_51254.jpg

Other notes:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

December 21, 2015

Discovering what you actually want in life

By Gordon Rugg

In a previous article, I looked at some ways of discovering what you want in life.

Those ways are a good start, but they often leave a lingering feeling that there’s something more that you actually want.

This article is about a quick, simple way of taking that next step.

Sources for the original images are given at the end of this article.

When I’m helping people to work out what they want their life to be like, one effective tactic is to ask them which of two arbitrarily chosen jobs they would prefer, and why. For instance, one job might be office manager while another might be office worker.

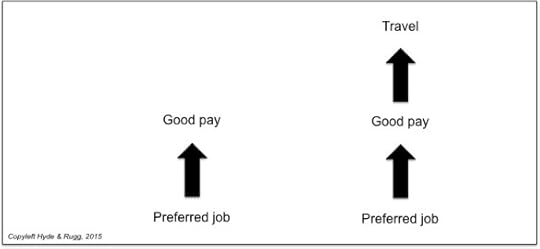

A common response is to prefer office manager, on the grounds that it would have good pay. I’ve shown this in the diagram below. It’s a perfectly reasonable response, but it’s a starting point, not an end point.

The next step is to ask a follow-up question, namely “Why would you prefer a job with good pay?”

It’s a simple question, but it usually produces unexpected and powerful new insights. The diagram below shows one common response to that follow-up question, namely that good pay would let the person travel.

Any readers who are familiar with laddering can guess what happens next. It’s the approach of two steps up, and one step down. Now that we’ve identified the higher-level goal of travel, we can look at ways of achieving that goal. One way of doing that is to ask: “What are some other ways of traveling, apart from having a job with good pay?”

I usually suggest a couple of answers, as a starting point; for instance, one way is to live abroad, and another is to be paid to travel – for example, as a travel writer.

This usually gets things moving. A typical pattern is that the person leaves with a thoughtful expression, and comes back a couple of days later with a keen expression and a batch of new insights about what they would love to do with their life. Quite often, those new insights are very different from the original preferred job, because of identifying much better ways of getting to that higher level goal.

It’s a good idea to pair this approach with some guidance about the practicalities of getting to higher level goals, since otherwise there’s a risk of people identifying a high level goal, and then becoming dispirited because they can’t see how to get there.

I usually do this by giving some examples that I’ve been personally involved with, such as students who have gone on to Hollywood consultancy, where I can go into detail about just how they got there, and how manageable the steps were along the way.

I usually combine this with pointing the person towards some of the classic resources for for the practicalities of achieving your dreams, such as What Color is Your Parachute? and its accompanying website (ignore the unflattering photo of its author – the book and site are both brilliant) and Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway.

I’ll return to the these themes in later articles. For now, though, I hope that you’ve found this article a useful step towards realising your dreams.

Notes and attributions for images

In case you’re wondering about the bonsai image in the banner: It was intended as an allusion to the concept of going up a couple of steps, and then branching out downwards. Some allusions work better than others…

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you retain the copyleft statement that goes with the image.

Banner image sources:

Hammock image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

Bonsai image: Slightly cropped version of:

“Bonsai IMG 6405”. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bonsai_IMG_6405.jpg#/media/File:Bonsai_IMG_6405.jpg

December 16, 2015

New cultural experiences

By Gordon Rugg

As regular readers of this blog will know, I’m interested in striking music. As regular readers of this blog will also know, I have a sense of humour that occasionally wanders into areas of unhallowed eldritch horror that would probably have been better left alone.

Today’s post includes both themes.

The link below is to some Tuvan throat singing, accompanied by a range of instruments; it’s striking and elegant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbxGP6fBma8

The next link is to a crossover between classic blues and Tuvan singing and music; some listeners (including myself) think that it’s brilliant, but others vehemently disagree.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U327iCwt_9k

The last link is to a crossover that was not such a good idea, namely throat singing combined with rap music. Much though I would like to describe it, like the famous quote about Wagner’s music, as not being as bad as it sounds, honesty compels me to remain silent…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuVLjAhsw-w

I hope that at least one of these experiences brightens your day.

December 5, 2015

New Hyde and Rugg website

By Gordon Rugg

The new version of the Hyde & Rugg website is now live, here:

Among other things, it contains a resource section which pulls together our articles on a range of topics, including academic craft skills for students, elicitation methods, requirements, design, and education theory.

There’s also a section about our research, plus a section on the codes we’ve worked on. Again, these pull together our previous blog articles into a structured framework.

Over the next few months, we’ll be adding more material, particularly in the sections on academic craft skills and on our research.

We hope that you’ll find the site a useful complement to this blog.

November 26, 2015

Genghiz Khan meets modern music

By Gordon Rugg

Regular readers of this blog will know that my tastes include an occasional penchant for dark humour. In that spirit, today’s article is about Genghiz Khan in popular Western culture.

For some reason, he inspired not only a film so bad that it’s now a much-cherished classic (until you’ve seen John Wayne playing Genghiz Khan, you haven’t savoured the true depths of bad movies) but also a song which is legendary for its kitschiness even by Eurovision standards. That song is the topic of this article, though I’ve detoured slightly into a mention of Barbara Cartland towards the end. If you wish to read more, you know what sort of unhallowed ground you will be entering…

Sources for the original images are given at the end of this article

Sources for the original images are given at the end of this article

So, here are the links. First, the Eurovision classic: The West German Eurovision Song Contest entry for 1979.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeXG9-wyzw0

If that isn’t enough to satisfy your taste for eldritch rhythmns that the human ear was never intended to experience, you can try the link below to Japanese girl band Berryz-Kobo’s cover of the same song. It’s quite memorable, though not necessarily in a sense that you might like.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtFSCvLLluw

Finally, as the closing experience, here’s Bauhaus performing their classic Bela Lugosi’s Dead. Unlike the two previous tracks, this is a classic for all the right reasons. It’s great music in its own right. It’s also the opening track to The Hunger, a brilliant,classic vampire movie that includes stunning performances by Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon. So why is it included here?

This version comes with the lyrics. If you want to push dark sensations to the limit, you might like to know that you can substitute “Barbara Cartland” for “Bela Lugosi” throughout, without interfering with the scansion, and you can also substitute “pink” for all of the colours in the lyrics while still maintaining the scansion. That’s what real horror is all about…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1U1SiIWuZeE

There’s no need to thank me for this; sometimes virtue is its own reward.

Or something like that.

Banner image credits:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan#/media/File:YuanEmperorAlbumGenghisPortrait.jpg

“Bela Lugosi as Dracula, anonymous photograph from 1931, Universal Studios” by unknown – Universal Studios. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bela_Lugosi_as_Dracula,_anonymous_photograph_from_1931,_Universal_Studios.jpg#/media/File:Bela_Lugosi_as_Dracula,_anonymous_photograph_from_1931,_Universal_Studios.jpg

“Dame Barbara Cartland Allan Warren” by Allan warren – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dame_Barbara_Cartland_Allan_Warren.jpg#/media/File:Dame_Barbara_Cartland_Allan_Warren.jpg

November 22, 2015

Life at uni: What do I do with the rest of my life?

By Gordon Rugg

It’s that time of year when final year students are uncomfortably aware that the rest of their lives will soon be starting, and that they don’t have a clue what they want to do with their lives, although everyone else seems to be reasonably sorted out and under control.

If you’re feeling like that, you’re not the only one. It’s an understandable feeling. This article is about non-threatening ways of moving towards finding out, and achieving, what you really want in life, particularly if you don’t even know what you actually want. It’s a story of hammocks and exotic sunny beaches and carnival masks. I’ll start with the masks.

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article.

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article.

First, masks.

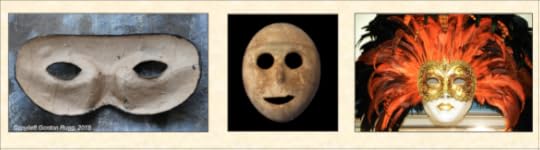

Most people suffer from low self-esteem to at least some extent, and this tends to lower their expectations about what they can achieve from life.

It’s an understandable feeling at one level; we see other people looking glamorous and successful, and we think that we are just ordinary. The reality, though, is different. Life is like a carnival where everyone wears masks. We see the outside of other people’s masks, looking like the gorgeous feathered and gilded creation below. However, we can only see the inside of our own masks, and masks on the inside usually look rough and ugly, like the one on the left below. That doesn’t help much with self-esteem. So, a useful starting point is to stop worrying about what the outward appearance of your mask may or may not be, and to start thinking about what you like and dislike in life.

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

One issue is that you can’t know what you don’t know; a related issue is that you can’t know how much you’ll enjoy something until you’ve given it a fair try. Both those points are true, but they’re easy to get past.

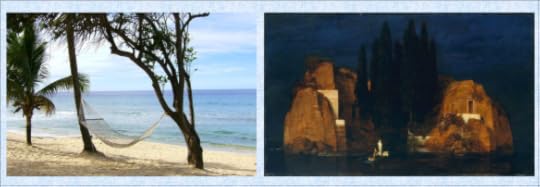

The pair of images below illustrate a couple of ways of starting to clarify what you really want to do with your life.

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

Sources for original images are given at the end of this article

The hammock is a nice, gentle place to start. Imagine that you’re in that hammock, looking back on a happy, fulfilling life, thinking how glad you are that you did X and Y and Z. What would X and Y and Z be? Don’t worry about whether you think they’re possible or not; in your ideal world, what would those things be that you look back on fondly?

If you’re more used to the grim daily grind, and you can’t face the thought of nice things, then you can use the flip side of the same process. Imagine that you’re looking at some contented soul in a hammock on a tropical beach, or that you’re being ferried to the Island of the Dead; what would you regret never having done or tried in your life?

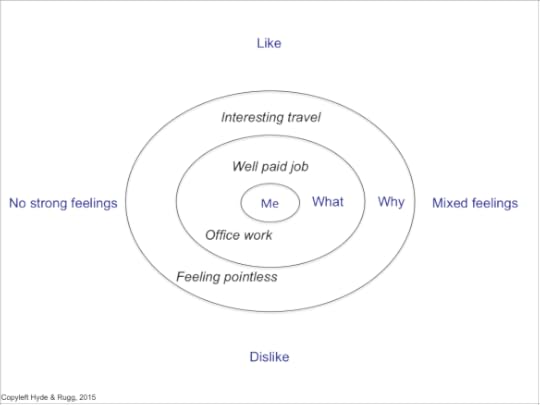

These two methods between them give you a list of concepts to start with. You can now plug them into the diagram below.

The “Me” at the centre is you, where you are now.

The first oval around you is about specific things that you like or dislike. For instance, you might like the prospect of a well-paid job, but dislike the prospect of office work.

The outer oval is about the reasons why you like or dislike something – your goals, values and motivations.

Some of the items on your list from the hammock/ferry session will belong in the inner oval, and some will belong in the outer oval.

You now go through each item in the inner oval, and work out why you feel as you do about that item. For instance, you might like the idea of a well-paid job because it would let you do interesting travel. You might dislike the idea of office work because of it feeling pointless to you.

The next stage is to stop for a while, and to sleep on it. You’ll probably find that your subconscious will produce a lot of good insights while you’re asleep, so you have a far clearer idea of what you really like and dislike in life.

You’ll now have a list of likes and dislikes. That’s a good start. How, you might be wondering, do you get from there to a good ending?

There are several ways.

One useful point to remember is that you don’t have to commit yourself forever to one path at this stage. It’s okay to decide that you’re going to take two or three years to try out some of the options that interest you, but that you’ve never experienced at first hand.

Another is to remember that there are usually many different ways of getting to any destination. For instance, there’s a standard set of requirements for getting onto a PhD, if that’s what you really want to do, but if you don’t meet those standard requirements, there are other ways of demonstrating that you’re suitably qualified.

This is where professional networking comes into the story. It’s emphatically not the same as favouritism, preferential treatment, corruption, or any of those other vices. It’s about asking people for the professional courtesy of giving you advice. If you’re polite and professional about it, people tend to be very helpful about this.

For students, the lecturing staff are a good place to start. You can book a meeting with an approachable member of staff, then tell them about your likes and dislikes, and ask their advice about career paths that might suit you. Often, they’ll know about possibilities that you’ve never heard of. Often, they’ll be able to put you in touch with someone who can help you along that path, by giving advice and information.

Another invaluable resource is the book What color is your parachute? This is solidly evidence-based; the advice in it is based on extensive sets of data. It’s an excellent guide to finding what you want to do with your life, and to making that happen. The website for the book is also excellent (though with a very unflattering photo of its author…)

Closing thoughts

This article was a quick introduction to the topic of working out what you really want in life. We’ll return to this topic in later articles, where we’ll look at approaches such as using card sorts to clarify your job and career preferences, and using laddering to work out your higher-level goals plus different ways of achieving them.

I hope that you’ve found this article a helpful starting point on the journey towards your own personal hammock on the beach…

Notes and links:

Banner images:

Hammock image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

“Venice Carnival – Masked Lovers (2010)” by Frank Kovalchek from Anchorage, Alaska, USA – Couple in love at the 2010 Carnevale in Venice (IMG_9534a). Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Venice_Carnival_-_Masked_Lovers_(2010).jpg#/media/File:Venice_Carnival_-_Masked_Lovers_(2010).jpg

Masks images:

Image of back of mask: Copyleft Gordon Rugg. You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you retain the statement that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

“Musee de la bible et Terre Sainte 001” by Gryffindor – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Musee_de_la_bible_et_Terre_Sainte_001.JPG#/media/File:Musee_de_la_bible_et_Terre_Sainte_001.JPG

“Venetian Carnival Mask – Maschera di Carnevale – Venice Italy – Creative Commons by gnuckx (4701305147)” by gnuckx – Venetian Carnival Mask – Maschera di Carnevale – Venice Italy – Creative Commons by gnuckxUploaded by russavia. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Venetian_Carnival_Mask_-_Maschera_di_Carnevale_-_Venice_Italy_-_Creative_Commons_by_gnuckx_(4701305147).jpg#/media/File:Venetian_Carnival_Mask_-_Maschera_di_Carnevale_-_Venice_Italy_-_Creative_Commons_by_gnuckx_(4701305147).jpg

“What and why” images:

Hammock image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HammockonBeach.jpg

“Arnold Böcklin – Die Toteninsel II (Metropolitan Museum of Art)” by Arnold Böcklin – 1. The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.2. Metropolitan Museum of Art, online collection. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arnold_B%C3%B6cklin_-_Die_Toteninsel_II_(Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art).jpg#/media/File:Arnold_B%C3%B6cklin_-_Die_Toteninsel_II_(Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art).jpg

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

November 14, 2015

Kites

By Gordon Rugg

Kites are an awesome invention. I’d originally thought of doing an article about concepts that they illustrate, such as why an anvil-shaped kite is amusing, but it’s a grim day in November, so I’ll just post some pictures of kites, as a reminder that life contains good things as well as bad.

A yellow kite against a blue sky “Festival of the Winds Bondi Beach (6136049188)” by Eva Rinaldi Celebrity and Live Music Photographer – Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Festival_of_the_Winds_Bondi_Beach_(6136049188).jpg#/media/File:Festival_of_the_Winds_Bondi_Beach_(6136049188).jpg

“Festival of the Winds Bondi Beach (6136049188)” by Eva Rinaldi Celebrity and Live Music Photographer – Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Festival_of_the_Winds_Bondi_Beach_(6136049188).jpg#/media/File:Festival_of_the_Winds_Bondi_Beach_(6136049188).jpg

A flying anvil “Catch The Wind 16” by Immanuel Giel – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catch_The_Wind_16.jpg#/media/File:Catch_The_Wind_16.jpg

“Catch The Wind 16” by Immanuel Giel – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catch_The_Wind_16.jpg#/media/File:Catch_The_Wind_16.jpg

An octopus kite “Catch The Wind 11” by Immanuel Giel – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catch_The_Wind_11.jpg#/media/File:Catch_The_Wind_11.jpg

“Catch The Wind 11” by Immanuel Giel – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catch_The_Wind_11.jpg#/media/File:Catch_The_Wind_11.jpg

Flower kites “Kites on the beach (5931155304)” by Mark Winterbourne from Leeds. West Yorkshire, United Kingdom – Kites on the beachUploaded by russavia. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kites_on_the_beach_(5931155304).jpg#/media/File:Kites_on_the_beach_(5931155304).jpg

“Kites on the beach (5931155304)” by Mark Winterbourne from Leeds. West Yorkshire, United Kingdom – Kites on the beachUploaded by russavia. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kites_on_the_beach_(5931155304).jpg#/media/File:Kites_on_the_beach_(5931155304).jpg

Kite seen through pines “A kite seen through the pine branches. Honshu Island. Japan” by Mstyslav Chernov/Unframe/unframe.com – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_kite_seen_through_the_pine_branches._Honshu_Island._Japan.jpg#/media/File:A_kite_seen_through_the_pine_branches._Honshu_Island._Japan.jpg

“A kite seen through the pine branches. Honshu Island. Japan” by Mstyslav Chernov/Unframe/unframe.com – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_kite_seen_through_the_pine_branches._Honshu_Island._Japan.jpg#/media/File:A_kite_seen_through_the_pine_branches._Honshu_Island._Japan.jpg

A jellyfish kite

“Jelly kites nach fabris02” by Sergio Fabris – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jelly_kites_nach_fabris02.jpg#/media/File:Jelly_kites_nach_fabris02.jpg

A dragon kite https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dragon_chinois_-_Dieppe_-_dsdm05111.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dragon_chinois_-_Dieppe_-_dsdm05111.jpg

Whales https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Festival_of_the_Winds,_XXXI_-_Festival_of_the_Winds_2013.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Festival_of_the_Winds,_XXXI_-_Festival_of_the_Winds_2013.jpg

A crane “Cerf-volant cigogne – Fanø – dsdm04773” by Pmau – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cerf-volant_cigogne_-_Fan%C3%B8_-_dsdm04773.jpg#/media/File:Cerf-volant_cigogne_-_Fan%C3%B8_-_dsdm04773.jpg

“Cerf-volant cigogne – Fanø – dsdm04773” by Pmau – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cerf-volant_cigogne_-_Fan%C3%B8_-_dsdm04773.jpg#/media/File:Cerf-volant_cigogne_-_Fan%C3%B8_-_dsdm04773.jpg

Green kites “Kites at Jeevan kite festival” by Subhrajit – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kites_at_Jeevan_kite_festival.JPG#/media/File:Kites_at_Jeevan_kite_festival.JPG

“Kites at Jeevan kite festival” by Subhrajit – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kites_at_Jeevan_kite_festival.JPG#/media/File:Kites_at_Jeevan_kite_festival.JPG

Anime figures “Kite festival Vung Tau 2009, 07” by Dream Phan – originally posted to Flickr as IMG_0068. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_07.jpg#/media/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_07.jpg

“Kite festival Vung Tau 2009, 07” by Dream Phan – originally posted to Flickr as IMG_0068. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_07.jpg#/media/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_07.jpg

Marine life: A ray, a shark and a whale

“Kite festival Vung Tau 2009, 08” by Dream Phan – originally posted to Flickr as Fishes. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_08.jpg#/media/File:Kite_festival_Vung_Tau_2009,_08.jpg

A Japanese-style carp kite “Heiligenhaus – kite festival 2007 22 ies” by Frank Vincentz – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heiligenhaus_-_kite_festival_2007_22_ies.jpg#/media/File:Heiligenhaus_-_kite_festival_2007_22_ies.jpg

“Heiligenhaus – kite festival 2007 22 ies” by Frank Vincentz – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heiligenhaus_-_kite_festival_2007_22_ies.jpg#/media/File:Heiligenhaus_-_kite_festival_2007_22_ies.jpg

I hope these have brightened your day.

November 2, 2015

Making the most of bad bibliographic references

By Gordon Rugg

Sometimes, you have to make the best of what you have, even if it isn’t great.

In the case of cookery, there’s a legend that Chicken Marengo was created when Napoleon’s cook had to produce a meal out of whatever he had been able to scavenge in the aftermath of the battle of that name; the result is one of the few recipes that combines chicken with crayfish.

In the case of academic life, there’s an all-too-common reality where you are trying to write something, and all you have in the way of references for one section is a stub from Wikipedia, plus an article from a newspaper which claimed in the same issue that Elvis had been sighted piloting a UFO in Spokane.

So, what can you do when you’re faced with this situation? Is there any way of salvaging something from the debris?

The answer is that you can indeed salvage something, and even emerge in a position of strength, provided that you handle it the right way, and that you don’t push your luck.

How you do that is the topic of today’s article.

A dish fit for a future emperor (ingredients not to scale, and without the parsley…) Sources for original images are at the end of this article.

Sources for original images are at the end of this article.

First, the bad news. If you don’t have any decent references at all, then you’ve got little option; you’ll need to go out and get some decent references. This article is about what to do if you’re short of good references for just one section.

Now, the good news. If it’s just one section that’s problematic, then you can probably fix it with a few carefully chosen words. The word “probably” is in there because this approach doesn’t guarantee success, any more than having the recipe for a masterpiece of French cuisine will guarantee that the meal you produce will be fit to eat; however, with a bit of luck, and some attention to detail, it greatly improves your chances.

In brief, what you do is the academic equivalent of holding your nose with one hand, while holding the offending horrible reference at arm’s length with the other hand, and thereby demonstrating that you are a proper academic who is showing professional disdain for work that falls far short of your exacting standards.

It’s a long-established approach. Here’s Thucydides the historian, using it two and a half thousand years ago.

For instance, there is the notion that the Lacedaemonian kings have two votes each, the fact being that they have only one; and that there is a company of Pitane, there being simply no such thing. So little pains do the vulgar take in the investigation of truth, accepting readily the first story that comes to hand.

The History of the Peloponnesian War, by Thucydides; translated by Richard Crawley.

http://classics.mit.edu//Thucydides/pelopwar.html

The classic way of using this approach is as follows.

First, demonstrate clearly to the reader that you’re a heavyweight professional. It’s a good idea to demonstrate this as early as possible, so that you get the halo effect working in your favour.

You can do this by, for example, including some references to the advanced critical literature; we’ve blogged about how to do that here.

Then, when you come to the section where you don’t have strong references, you can cite your horrible references by using introductory phrasing such as: “There is a popular belief that…” or: “There have been claims that…”

Ideally, you would then follow this up with a proper, respectable reference by way of contrast, to distance yourself further from the vulgar, erroneous version of events. However, if you don’t have a decent reference, you can simply move on fast to the next section, where you return to respectable references that will get you decent marks.

In case you’re wondering whether the advice above is about cynically manipulating the reader, the answer is that you won’t get away with using this approach unless you have good references to use in juxtaposition with the bad ones.

It’s also a useful approach for some situations that can affect even the best professionals.

Sometimes, for instance, a key fact is so well established that there isn’t a good reference for it, or it’s so well established that citing a reference for it would give the impression that you didn’t know the difference between assertions needing a reference and assertions not needing a reference. If you’re an archaeologist, for instance, you probably wouldn’t want to use a reference saying that the Egyptian pyramids were built by ancient Egyptians (because that would be so obvious that people would wonder why you were saying it) but you might disdainfully quote an ancient aliens claim as a way of visibly distancing yourself from people with interesting hair and even more interesting beliefs…

A related situation is where there are two or more concepts that could easily be confused with each other. For instance, the acronym “NLP” is widely used in academic computing to refer to “Natural Language Processing” but is widely used outside academia to refer to the very different concept of “Neuro-Linguistic Programming”. It’s a courtesy to your readers to make them aware of this type of ambiguity, to avoid confusion; it’s also a good way of salvaging some credibility if you belatedly discover that you’ve been diligently reading papers from the wrong literature.

An example of handling this would be “… X (Smith & Jones, 1976). This is not to be confused with the popular concept of Y (e.g. Dreck & Grot, 2015)”.

So, in summary, you can make good use of a small number of horribly low-quality references by citing them, and showing the reader just how much disdain you have for them. You still have to do the hard work elsewhere in what you’re writing, but this approach can help you when you’re up against a hard deadline and making the best of what you’ve got, or when there’s not much point in trying to track down a solid reference that might not even exist yet.

Notes and links

Banner image original sources:

“Female pair” by Andrei Niemimäki from Turku, Finland – Friends. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_pair.jpg#/media/File:Female_pair.jpg

“Italian garlic PDO” by Pivari – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Italian_garlic_PDO.JPG#/media/File:Italian_garlic_PDO.JPG

“Bright red tomato and cross section02” by Taken byfir0002 | flagstaffotos.com.auCanon 20D + Sigma 150mm f/2.8 – Own work. Licensed under GFDL 1.2 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bright_red_tomato_and_cross_section02.jpg#/media/File:Bright_red_tomato_and_cross_section02.jpg

“Flickr – cyclonebill – Vagtel-spejlæg” by cyclonebill – Vagtel-spejlæg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_cyclonebill_-_Vagtel-spejl%C3%A6g.jpg#/media/File:Flickr_-_cyclonebill_-_Vagtel-spejl%C3%A6g.jpg

“Austropotamobius pallipes” by David Gerke – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Austropotamobius_pallipes.jpg#/media/File:Austropotamobius_pallipes.jpg

Notes:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

We’ve written more about academic insults here:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/31/the-studied-subtexts-of-academic-insults/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

October 26, 2015

Creativity and idea generation

By Gordon Rugg

So what is creativity, and how can you generate more and better ideas?

There’s pretty general agreement that:

Creativity is a Good Thing

Thinking outside the box is a Good Thing

Thinking laterally is a Good Thing

That’s a good start.

However, when you start asking about how creativity works, or just how you’re supposed to think outside the box, or think laterally, an element of vagueness starts to roll in, like a dense bank of fog off the Atlantic at the start of a horror movie…

You start hearing stories of people and organisations that thought successfully and laterally outside the box, in a way that solved their problems with designing better elevators. You encounter puzzles involving people and items being found in improbable situations, such as stabbed to death with no weapon visible, in the middle of a field of unsullied snow. It’s all very edifying and interesting, but it doesn’t get to grips with what creativity really is, or how to do anything systematic about creating new ideas.

This article gives a brief overview of a systematic framework for making sense of creativity, and for choosing appropriate methods for generating new ideas.

The framework in this article is based on a distinction between three levels of knowledge, namely explicit, semi-tacit and tacit.

We use this distinction a lot in our work; it’s invaluable for making sense of what would otherwise appear to be a tangled mess. Each of these three levels can be divided into sub-types, as described in a previous article, but I’ll stick with three levels for simplicity and clarity.

Mapping creativity methods onto knowledge types: Explicit knowledge

Explicit knowledge is what most people think of as ordinary, straightforward knowledge; it’s things like your name, or the number of days in June, or the capital city of France.

Explicit knowledge often involves serial processing, i.e. step by step reasoning with “facts”.

If you now start looking for idea generation techniques that work with explicit knowledge and serial processing, you soon discover methods such as systematic constraint relaxation. This is a method which is serial (as in the “systematic” part of the name) and explicit (as in the “constraint relaxation” part of the name).

In systematic constraint relaxation, you start by producing a written list of constraints that limit you when tackling a problem. For instance, if you’re an architect designing a skyscraper, then the constraints for lifts (“elevators” in the USA) might include:

Must hold at least seven people

Must hold at most 25 people

Must be on the inside of the building

Must be fully enclosed

The next step is to throw away each constraint in turn, and see which new ideas emerge.

For instance, if you throw away the constraint of must hold at least seven people, then you might have the idea of one-person lifts. These would have some strong advantages, such as increased speed (because the lift wouldn’t stop at any intermediate floors between starting point and destination) and increased security (because the user wouldn’t need to worry about potential criminals getting into the lift with them). They would also have disadvantages, but that isn’t the point; the key point is that you only need to generate one really good idea to make the session worth doing, so you concentrate on generating the ideas first, and then thinking through the details later.

Here’s a real life example of what happens when you throw away one of those constraints. Just in case you’re wondering, yes, the yellow blob is an elevator, and yes, it’s on the outside of the building, with a very long, very visible drop beneath it. It’s very popular with some users, but not with others…

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

You can use different ways of deciding which constraints to throw away – for instance, you might only throw one away at a time, or you might throw away more than one at a time, or you might rank them in terms of current cost of the constraint, or some other criterion.

You can also combine this approach with other methods, such as scenarios to get a richer understanding of problems with the current constraints, or Multi-Criterion Decision-Making to assess the ideas that you generate.

This is a useful method for dealing with explicit knowledge and serial processing. However, that only applies to some problems. More often, you’re dealing with semi-tacit or tacit knowledge, and with parallel processing and pattern matching.

Mapping creativity methods onto knowledge types: Semi-tacit knowledge

Semi-tacit knowledge is knowledge that can be accessed using some techniques, but not all techniques. (Interviews, focus groups and questionnaires are usually between bad and useless for dealing with semi-tacit knowledge; questionnaires in particular can be worse than useless if they produce impressive-looking statistics that are actively misleading.)

In the case of lift design, for instance, a lot of women don’t like using lifts late at night because of the risk of being assaulted while inside, with no way of escaping. However, they might not be keen on saying so in as many words, particularly if they’re being interviewed by a clueless male engineer.

Another classic problem is that people will recognise something as being highly relevant when they see it, but won’t think of it otherwise.

These examples demonstrate a couple of sub-types of semi-tacit knowledge; there are numerous others.

One effective way of taking semi-tacit knowledge into account when generating ideas is to use Idea Writing. We’ve written about it in a previous article, here. In brief, it involves writing a group of people sitting round a table. They start by each writing ideas at the top of sheets of blank paper, one idea per sheet; they pile the sheets in the middle of the table, and then pull out a sheet at random, and write a constructive comment on it, then return it to the pile. The illustration below shows a fictitious example.

This method involves everyone working at the same time (so you don’t get people having to wait for their turn) and working in silence (so the group doesn’t get dominated by aggressive or long-winded individuals). It’s also fairly anonymous, if the group aren’t familiar with each other’s handwriting. This combination of features helps you to access sensitive topics that might otherwise not be mentioned (a common form of semi-tacit knowledge).

The format also means that people can recognise interesting ideas in the previous comments, which will be likely to spark off further ideas in their own mind, tapping into another form of semi-tacit knowledge.

A practical advantage of this method is that it’s self-documenting; you don’t need a scribe to record what people say, and you can simply photocopy or scan the sheets at the end of the session, then circulate them to everyone who wants them.

Mapping creativity methods onto knowledge types: Tacit knowledge

Tacit knowledge is defined in different ways by different disciplines. We use the term in a strict sense, to describe real knowledge or skill that the individual can’t validly introspect into. When you deal with experts, you often see them demonstrating impressive skills, but you often find that they can’t put those skills into words. You also often find that when the experts do try describing their skills in words, their descriptions don’t actually correspond very well with reality.

Tacit knowledge often involves “gut feel” and “intuition” and other concepts that are usually treated as semi-mystical black boxes.

In this article we’ll focus on one aspect of tacit knowledge that can be fairly easily explained without using mystical terms. It’s deep structure pattern recognition.

Deep structure is a concept that crops up in a wide range of places, from linguistics to film theory and bridge design. It’s about the underlying regularities that you see when you strip away the surface detail. In story telling, for example, there’s a common deep structure ending in which the protagonist defeats the villain. The surface features may vary; for instance, this deep structure may take the form of Ripley kills the alien queen, or Arnie shoots the bad guy, but it’s the same deep structure underneath the different surface forms.

Pattern recognition is what it sounds like; you recognise a pattern. This is something that humans do extremely well. It’s only when you try writing pattern recognition software for computers that you realise just how ubiquitous pattern matching is in everyday human life, and just how different it is from step by step sequential thinking.

There are various forms of pattern matching; for instance, one form is recognising the face of someone that you know.

In this article I’ll focus on pattern matching in which you see a deep structure that matches what you’re looking for.

The classic example is an engineer looking at a reconstructed dinosaur, such as the one below, and seeing that the deep structure of the dinosaur’s body structure is the same as the deep structure of a cantilever bridge, such as the one below. This is a genuine mechanical deep structure match, not just a coincidental resemblance, and it’s given a lot of useful insights to palaeontologists about how dinosaur anatomy worked.

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

(Picture credits at the end of this article)

You can apply this principle to creativity by simply showing people arbitrary images, and letting the people look for deep structure pattern matches within those images, for instance via a PowerPoint slide show. Most of the images won’t spark any recognition, but some probably will, either immediately, or via stirring subconscious associations that will bubble to the surface much later.

There’s a temptation when using this approach to choose images that you think ought to be relevant, but that temptation should be avoided. The key point of this approach is that you’re using it because the obvious approaches (such as looking for solutions in places that ought to be relevant) haven’t worked, so you need to look somewhere else.

Because the pattern recognition process is non-verbal, the result is often an “aha” experience that occurs instantly, with no conscious reasoning involved, making the process hard to put into words, which is why it is often viewed in semi-mystical terms.

A key advantage of this method is that it deliberately bypasses the need for words, and lets the participants focus on the pattern recognition that is at the heart of the method.

Closing thoughts

This article described a swift overview of a way of approaching creativity and idea generation in a way that is systematic, and that is based on the underlying mechanisms involved in creativity and idea generation.

We’ll return to these themes in later articles; we’ll also return to deep structure and surface structure.

Attributions, notes and links

“AmpelosaurusDB” by ДиБгд at Russian Wikipedia – Transferred from ru.wikipedia to Commons.. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AmpelosaurusDB.jpg#/media/File:AmpelosaurusDB.jpg

“Pierre Pflimlin UC AdjAndCrop” by Image Adjustment by User:Leonard G. – See below. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre_Pflimlin_UC_AdjAndCrop.jpg#/media/File:Pierre_Pflimlin_UC_AdjAndCrop.jpg

“Niagara falls fallsview 04.07.2012 15-25-48” by Dirk Ingo Franke – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Niagara_falls_fallsview_04.07.2012_15-25-48.jpg#/media/File:Niagara_falls_fallsview_04.07.2012_15-25-48.jpg

Notes and links:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/200-posts-and-counting/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers