Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 10

May 26, 2015

People in architectural drawings, part 6; conclusion

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the last in a short series about finding out what people really want. I’ve explored that topic via discussion of idealised dream buildings, to see what regularities emerge and what insights they provide into people’s dreams and desires.

In today’s article, I’ll pull together strands from those discussions, and see what patterns emerge.

Detail from: “Neuschwanstein Castle above the clouds” by Arto Teräs – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neuschwanstein_Castle_above_the_clouds.jpg#/media/File:Neuschwanstein_Castle_above_the_clouds.jpg

Surface appearances

Idealised buildings tend to be tall, gleaming and elegant. They’re pretty to look at.

Beneath this apparently simple observation, there’s a deeper set of regularities in what people like, and what people want.

One set involves life scripts, in the Transactional Analysis (TA) sense. These take forms such as “bigger than yours” or “look how humble I am” or “blending in with the crowd”. These scripts have big implications for sustainability, because some of them by their very nature produce systems pressures in a particular direction. An architectural example is the competition among architects and developers to produce ever taller skyscrapers, regardless of whether there is any real need for anything over half a kilometre tall. At a humbler level, there’s the familiar script of “being one up on the Joneses” producing a pressure for bigger and more expensive houses, cars, etc.

It’s important to note that life scripts don’t all produce systems pressures in the same direction. There are scripts such as “blending in with the crowd” and “keeping it simple” which produce pressures towards stability, or towards downsizing.

This is where social institutions, such as tax systems and planning regulations, can weight the payoffs from different life scripts into different directions, and channel competitive life scripts in ways that are less likely to cause collateral damage to society at large. For instance, if there was a high-prestige award for most accessible building or for most family-friendly building, there would probably be significant changes in the focus of architectural design, towards more human-centred features.

A related issue involving outward appearance is the perception of buildings as 3D sculptures versus buildings as functional artefacts.

This takes us into the mathematics of desire; the regularities underlying many of human aesthetic preferences. I’ve blogged about this previously, with particular reference to a fascinating article on the topic by Ramachandran and Hirstein. This is also the topic of an entire chapter in my book Blind Spot, where I pick up on some of the possible implications. For instance, people tend to prefer symmetry where possible, with balance as a second preference if symmetry isn’t possible.

This shows up strongly in the design of buildings, but also in other areas, such as justice (e.g. the idea that the punishment should mirror the crime) and in beliefs about history (e.g. the idea that major events should have major causes, as opposed to the “butterfly’s wing” concept that a small cause may lead to major effects).

Surface appearance versus deeper reality is another problem with far-reaching implications, if people are treating buildings as giant sculptures.

Human beings are very good at processing visual information and seeing patterns within it. However, human beings are really bad at working through things step by step. In more technical terms, people are very good at parallel processing and pattern matching, but not very good at serial processing. I’ve written about this crucial distinction previously here.

In the case of buildings and of life dreams, these characteristics mean that humans are likely to be seduced by the outward appearance of a visually beautiful building or lifestyle, and likely to fail dismally at thinking through the implications. A lot of wonderful dreams crash in a heap when they hit brutal questions such as “Who would clean it?”

This doesn’t mean that all beautiful designs and beautiful dreams are built of candyfloss on a foundation of clouds. On the contrary, a lot of designs and dreams are beautiful because they have a brilliant design, where form and function mesh seamlessly. This is where brutal questions and careful task analysis can help, by quickly separating the superficially attractive from the deep-down attractive.

Keeping it too simple

A lot of dream houses and dream lifestyles are simple, without the messy clutter that occurs everywhere in the real world.

There’s a strong argument that this type of simplicity is attractive to people because it reduces cognitive load. Human beings have to spend a lot of time working out solutions to messy, minor, problems that are too big to be ignored, but too small to give any feeling of satisfaction when you solve them. In a dream world, such as the ones portrayed in most architectural designs, life is free of such mundane trivia, so clean-limbed, strong-jawed heroes and heroines can stride purposefully towards their noble goals without having to worry about whether the next paving slab is loose, or whether the next door is pushchair-friendly.

Unfortunately, that isn’t how the real world works. Designs need to be grounded in the realities of the world, not in a set of fantasies.

This leads us into the next theme, which is about human perceptions of reality.

Construing, fantasy and reality

At one level, there’s a well-established distinction in western society between reality and fantasy. A particularly useful concept is that of suspension of disbelief, where the person knows that something is fantasy, but is choosing to treat it as real for the purpose of entertainment.

At another level, though, the distinction isn’t always so clear. Again, this brings us back to human weakness in sequential logic.

People are fairly good at seeing what might happen from a given situation. They’re far less good at assessing how likely a possible outcome is.

One useful way of describing these strengths and weaknesses is via the concept of possibility spaces. For instance, buying a lottery ticket opens up the possibility space of winning a fortune on the lottery. Winning a fortune on the lottery then opens up the possibility space of buying a mansion. Does this mean that you’re likely to win a fortune on the lottery? That’s a whole different question. At one level, winning the lottery and buying a mansion is a fantasy, because it’s not realistically likely to happen to the person buying a particular lottery ticket. At another level, though, it’s a real possibility; someone is going to win the lottery, and that person will be one of the people who bought a ticket, not one of the non-buyers.

This leads in to classic optimism bias, which is also more complex than it appears at first sight. More than one error researcher has pointed out that optimism bias is what keeps humanity going as a species. If we all made “rational” decisions not to find partners, have children, apply for jobs or try anything new, on the grounds that statistically most of those attempts would fail, then humanity would die out pretty rapidly. On the other hand, if you’re having to wrestle with a building design that causes you a lot of hassle because the designer was optimistic about how the design would work out, then you’re likely to take a dim view of this particular bias…

Closing thoughts

So, what can we conclude about people’s dreams and desires from looking at idealised dream buildings?

Life scripts are important

Some life scripts introduce competition and instability; others don’t

People are disproportionately influenced by surface appearance

There are regularities in what people like in surface appearances

People aren’t usually good at thinking through implications

The line between fantasy and reality isn’t clear cut

One particularly important theme that’s been in the background throughout this set of articles is a deceptively simple-looking concept: People can’t know what they don’t know.

For life goals and dreams, people can’t know the full range of what’s possible. This has huge, far-reaching implications for areas such as politics. How can you make decisions about public policy if the voting public can’t know what they don’t know, and if they’re therefore limited and biased in what they ask for and vote for?

This is pretty much the same question that’s at the heart of finding out what a client’s requirements are. Fortunately, there are well-established methods that let you tackle the problem swiftly and efficiently. I’ve written about this in various earlier articles on this blog, both from the viewpoint of requirements gathering and from the viewpoint of design. The section on elicitation in this article gives an overview, and contains links to those articles.

There’s been a fair amount of research into using similar approaches to investigate people’s dreams and goals. Some of it has been in market research, such as Gutman & Reynold’s use of laddering to unpack goals and values. Some of it has been in clinical psychology and related fields, such as work in the Personal Construct Theory tradition that used repertory grids and laddering for very similar purposes.

As far as I know, there hasn’t been much research into systematically using the more recent work from requirements acquisition to investigate people’s desires and dreams. It’s a topic that I’m getting into, via various strands of research, in spare moments when I’m not dealing with messy, minor, problems that are too big to be ignored, but too small to give any feeling of satisfaction when I solve them…

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/05/15/mapping-smiles-and-stumbles/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/05/12/observation-stumbles-and-smiles/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/03/20/peoples-dream-buildings-part-1/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

May 15, 2015

Mapping smiles and stumbles

By Gordon Rugg

In a previous article, I looked at ways of systematically recording indicators of problems and successes with a design. In that article, I focused on the indicators, with only a brief description of how you could record them.

Today’s article gives a more detailed description of ways of recording those indicators, using the worked example of a building entrance.

The worked example is, ironically, the Humanitarian Building. Here’s the Wikipedia image for its entrance.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MSU_III_Humanitarian_Building_Entrance.jpg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MSU_III_Humanitarian_Building_Entrance.jpg

When you look at it from a task analysis viewpoint, you soon spot potential trouble. Here’s a close-up that shows one source of possible complications.

The ground outside the building slopes slightly. The entrance design tackles this by having a flat surface immediately outside the entrance, and then having a small step (indicated by the red arrows) between that flat surface and the sloping approach routes.

The phrase “small step” is usually a synonym for “stumbles and swearwords waiting to happen”. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the designer got it wrong. The easiest alternative would be to handle this problem via a change of slope, but the phrase “change of slope” is also usually a synonym for “stumbles and swearwords waiting to happen”. Another option would be some significant re-working of ground levels, which would probably entail a whole batch of new problems. It’s a non-trivial design problem, without a single perfect solution.

If you superimpose likely pedestrian flight paths over this image, plus the door footprint for when the door opens, you get something like this.

I’ve shown three flight paths that are particularly likely to be used, and omitted the others, for clarity. One flight path goes to the left, along the path to the left. Another goes to the main pavement, heading left, and cutting as close as possible to the flower bed; the third goes to the main pavement, heading right, and again cutting as close as possible to a flower bed. There’s also a significant flight path along the path to the right, but I haven’t shown that in the image above, to avoid visual clutter.

All three of these flight paths either go over the small step, or go next to it. It’s a pretty fair bet that this will end in tears before long. Either someone will not notice the step and will stumble over it, or someone will avoid the step, but will have a collision with someone who has missed it and has stumbled.

That’s what is likely to happen. As for what actually happens, you can record that systematically with a variant of the task analysis method I described in the previous article.

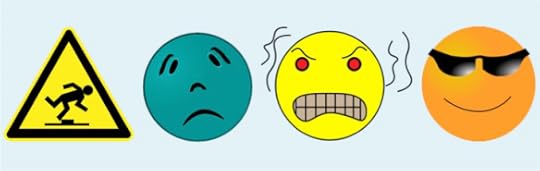

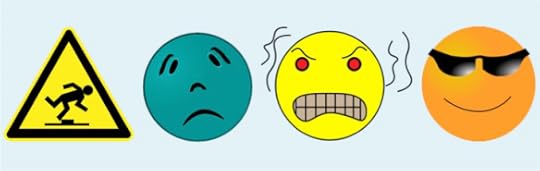

I’ll use the same icons that I used in the previous article, for simplicity. Here are the icons.

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article.

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article.

One simple way of using them is to observe the place in question, and to record what happens by drawing the relevant icons on a photo of the place. This is classic “observation with a clip board and pen” and involves the usual points about getting ethical clearance if you’re a student, getting permission from the relevant authorities about being on the premises, letting Security know what you’re doing so you don’t get arrested for loitering suspiciously, etc. If you’re not familiar with these issues, it’s wise to pick the brains of someone knowledgeable.

Here’s a hypothetical example of what you might get from this approach, showing only the “stumble” yellow triangles, for clarity. I’ve copied and pasted the icon; if you were doing this with a clipboard and photo, you could just draw triangles with a pen or highlighter, or you could use small sticky labels; whatever works well for you.

This hypothetical image shows several clusters of triangles, where each triangle represents a stumble or a change of gait from walking smoothly. If you need quantitative as well as qualitative data, you can count the triangles, and/or count the triangles in each cluster.

The image below shows how these map on to the predicted flight paths. This time, I’ve included the flight path towards the footpath to the right, for completeness.

The clusters and the flight paths map onto each other as neatly as you might expect from a hypothetical example. (Ironic smile…) However, there’s plenty of empirical evidence from fields such as architecture to show that this type of identification of trouble spots is practical, useful, and able to produce unexpected insights. There’s been a lot of research, for instance, into pedestrian traffic flow in built environments, with particular regard to preventing bottlenecks and other hazards that can lead to crowd crushes in emergency evacuations of a building.

In this example, I’ve only shown records of stumbles. You can do exactly the same with the other icons. If your recording sheet starts to get cluttered, then you can record the time when you stop using it, and start using a new recording sheet; you can collate the results from the various sheets afterwards, when you’re back in the office.

Here’s another hypothetical example, showing multiple icons – stumbles, puzzled scowls where someone is deciding which route to take, and swearwords after stumbling. I’ve used bigger icons in this image, for clarity.

Finally, on a note of sympathy for the designer faced by a tricky problem, here’s an image showing the positive side of this solution. Whatever its other limitations, at least this design includes a route to the entrance for people with wheelchairs, child buggies, and other forms of wheels. If you search for images of building entrances, you’ll probably be surprised by how many entrances are at the top of a set of steps, with no provision for wheeled access. So, as a token of appreciation, here are some smiling icons as a positive closing note.

Notes and links

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of icon images:

https://openclipart.org/detail/14453/trip-hazard-warning-sign

https://openclipart.org/detail/190668/frown

https://openclipart.org/detail/215785/yellow-angry-head

https://openclipart.org/detail/22035/smiley-cool

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

May 12, 2015

Observation, stumbles and smiles

By Gordon Rugg

If you’re designing something that’s going to be used, as opposed to something decorative, then it’s a really good idea to make it fit for its purpose.

How can you do that? Observing the users is a good start.

“Observing” is a broad term that includes various specialised forms of observation and analysis. In this article, I’ll describe a simple way of doing basic observation of users, which involves watching out for four key alliteratively-named actions:

stumbles

scowls

swearwords

smiles

It’s simple, but it’s powerful, and it usually catches most of the main problems, and it gives you a good start towards designing something that the users will like.

Not great art, but useful: Four things to watch for in task analysis

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article

Observing

“Observing”at the most basic level is what it sounds like; you observe what someone does. I’ve blogged about various forms of observation previously, including a general overview, structured observation of the environment (STROBE), and ways of recording what you observe, such as timelines and tally sheets.

You can gather a fair amount of useful information just by watching and looking for regularities in what happens. However, that simple approach only gets you some of the way.

One problem with the simple approach is that you’ll probably overlook a lot of important regularities precisely because they’re so familiar that you take them for granted, or view them as not worth mentioning.

Another problem with the simple approach is that it doesn’t give you any numbers that you can use for purposes such as assessing which regularities are most important or most common.

One simple, practical way of recording your observations more systematically is to use a timeline chart, such as the one below, from one of our previous articles.

Copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2015

This particular chart is designed to let you track the sequence of actions performed by one person, action by action. Each column is a time slice, starting at the left. In this example, the person starts by reading something (shown by the tick in the first column) and then hesitates (the tick in the second column), then clicks on an option, puts in text, and then swears.

This type of chart is useful for identifying where things go wrong; you can work back from the swearword and see what came before it.

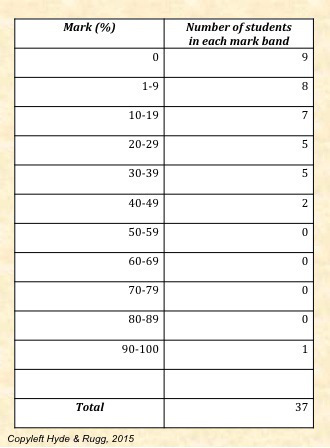

This basic design of chart can easily be adapted to record other aspects of observation. For instance, suppose that you want to record what people do once they walk through the door of a medical practice or hospital. It would be useful to know how many people hesitate, as opposed to walking straight on towards their destination; it would be useful to know how many people read instructions and signage. You can record this by using a tally chart, where you tick the relevant row every time someone performs a particular action, as in the example below. You then count the ticks in each row, once you’ve finished collecting the data.

Copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2015

This raises the question of how you know which actions you should record. There are various answers.

One answer is to get the actions from a critical review of the relevant literature. That can be very useful if you’re looking for actions whose significance you might have missed otherwise; previous researchers may well have spotted that significance.

Another answer is to look for any departure from “not committing a breach of the peace”. It’s a well-established joke in Britain that almost anything can be construed as a breach of the peace by a suspicious police officer. A cynical legal commentator once commented that walking in silence while breathing through the nose and looking only at the route ahead was probably just about okay; anything else could be construed negatively.

The way that this translates into observation is that you can treat “walking in silence while looking only at the route ahead” as the default activity. You can then notice when someone departs from that activity in any way; for instance, by making eye contact with someone, or by slowing down, or by saying something. Any of these departures might be a suitable action to include in your recording; you’ll need to use your judgment.

Some of those other activities are clearly planned and intended. Others, however, aren’t. Those are the topics of today’s article. Three of them are indicators that something has gone wrong (so you know that something needs to be fixed). One of them is usually an indicator that something has gone well (in which case, something needs to be kept in).

The next section goes through each of these in turn.

Stumbles

I’m using the word “stumble” here in a broad sense, to describe any sudden break in a previously smooth pattern of actions. Examples include:

a sudden change from walking smoothly to walking irregularly, or tripping

a sudden change from using a computer interface swiftly and confidently to hesitating or stopping and reading instructions

a sudden change from talking fluently to talking in broken phrases, using hesitation noises, or silence

I’ve blogged previously about how you can use this approach to identify significant points in a transcript, when the speakers suddenly realise that something unexpected has happened that they don’t understand.

In a lot of cases of stumbles, what is involved is a switch from a compiled skill to deliberate reasoning. Compiled skills are known in different fields under different names, such as “muscle memory”. They are skills that are so well practised that the person can perform them without the need for conscious thought.

Not needing conscious thought is a great advantage of compiled skills, since they free the brain up for doing other tasks at the same time – for instance, talking while doing routine driving. This is one reason why walking in a busy street is usually much more tiring than walking the same distance in a quiet street; in the busy street, you’re constantly having to switch out of walking as a compiled skill because you need to adjust pace to avoid bumping into the person in front of you.

If you’re designing a product, whether it’s a computer interface or a toaster or a building, it’s a good idea to design it so that the user can work with it smoothly, without stumbles.

This is at the heart of the concept of the transparent interface for software; it’s an interface so easy to use that it doesn’t require conscious thought, and the user doesn’t even notice it.

When you start looking for stumbles, you soon notice how common they are. Automatic doors are a good example. A lot of them only start opening when you’re very close to them, so you have to change your walking pace to avoid colliding with them.

People don’t usually like having to switch from a compiled skill into having to use deliberate thought, so when this happens, you often observe one of the next two actions.

Scowls

I’m using “scowl” in a broad sense, to include expressions of puzzlement as well as annoyance. A common pattern is a frown, followed by looking more closely at whatever caused the problem.

This is often the point where people read the instructions, such as “pull” on a door that they have just tried to push. Reading instructions is another example of deliberate thought, and people usually only use deliberate thought (and reading) as a fallback strategy, not as a first choice.

Swearwords

Swearwords are invaluable to anyone designing a product or a system, because they tell you clearly and audibly that a problem is significant. Problems that regularly cause swearing are problems that go high on the “to fix” stack.

If you’re working with data collected by someone else, swearwords are something to check for. If there aren’t any swearwords in a transcript, or the swearwords are only mild ones, then you need to wonder whether the transcriber has edited them out or toned them down. If so, you need to wonder what else the transcriber might have got up to.

If you hear angry swearwords when you’re observing someone who’s trying out a product that you helped design, there’s a strong temptation to try to defend or explain the product to them. It’s a temptation that you need to resist. If that product is rolled out commercially to tens of thousands of users, you won’t be sitting there next to each of them to explain it. The product has to be good without your explanation.

What you need to do instead is to practise putting yourself into the tester’s position, and seeing things through their eyes, and working out where the product didn’t behave in the way that they wanted or expected. Then you can start working out how to make it behave in a way that they will like, which leads us on to the next type of response.

Smiles

When you get a design really right, you know about it in two main ways.

One is an invisible compliment; the product or service works so smoothly that people don’t notice it.

The other is much more immediately gratifying. You see users smiling, or you see a metaphorical light bulb switch on above their head as they realise what they can do with the thing that you’ve designed, or you hear them saying “wow” or good swearwords. It’s a very, very satisfying moment.

Which is a good note on which to end.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of images in the banner:

https://openclipart.org/detail/14453/trip-hazard-warning-sign

https://openclipart.org/detail/190668/frown

https://openclipart.org/detail/215785/yellow-angry-head

https://openclipart.org/detail/22035/smiley-cool

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

May 1, 2015

People in architectural drawings, part 5; common requirements

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the fifth in a short series about finding out what people would really like in life, using architectural drawings and fantasy buildings as a starting point.

The first article discussed how this gives you insights that you wouldn���t get from an interview or questionnaire. The next articles looked at regularities in people���s preferences; at changes in preferences over time and at obsolescence; and at complicating factors that you need to keep in mind when using this approach.

In today���s article, I���ll look at ways of identifying common user activities and requirements that should be incorporated into the design process, and that can be handled cheaply and simply, producing significantly better designs as a result.

This article gives a brief overview. I���ll re-visit this topic in some later articles, which will work through some specific cases in detail.

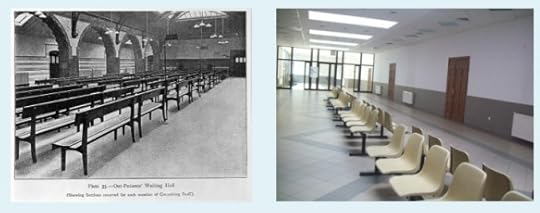

A thing of beauty is a joy forever: Waiting rooms, however, usually aren���t… Sources of original images are given at the end of this article

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article

For today���s article, I���ll use the underlying theme of a visit to the doctor, focusing on two particular activities.

If you watch what happens when people go to visit the doctor, you see two stages in the process that are familiar to pretty much everyone. One stage is checking in, to let the medical practice know that you���ve arrived; the other is waiting for the doctor to call you through.

Different practices have different ways of handling these stages.

Arrival

One common arrangement is that when you arrive, you let one of the reception staff know that you���ve arrived. That���s a perfectly sensible arrangement. However, if you start thinking about the details of how this is handled within a given medical practice, you soon start noticing potential problems.

Within the compass rose approach to requirements gathering, one thing you need to look for is the worst cases. In the case of anything medical, one of the worst cases is having to talk about your private medical issues in front of people who shouldn���t know about them.

An obvious way of handling this worst case is to make sure that the reception area is out of earshot of other patients. Some practices handle this by having different rooms for the waiting room and the reception area. Others don���t.

A related issue is waiting in a queue to report to the receptionist. Queues are a much richer, deeper topic than most people realise; there���s an entire body of maths called queueing theory, which deals with the best ways of managing queues not just of people, but also of things such as internet traffic.

One deceptively simple-looking part of managing human queues is how someone in the queue can tell whether or not it���s their turn to go forward. The railway station at Stoke-on-Trent is an example of getting it right. There���s a queueing line outside the ticket office; there���s a glass wall between the queue and the ticket office, so people in the queue can see when one of the ticket staff is free. This arrangement is simple and effective, and ironically gives more privacy to ticket purchases than patients get in most medical reception areas.

A less obvious problem with knowing when it���s your turn involves people with sensory issues, such as visual impairment. If you have visual impairments, you���ll probably have difficulty telling whether or not a receptionist is trying to catch your eye to tell you that they���ve finished the paperwork from the previous patient and are now ready to see you. If you have hearing impairments as well, you���ll quite possibly have problems hearing the receptionist telling you that they���re ready for you now.

One response to this is to ask how often this particular combination of problems is likely to occur. A lot of design, both of buildings and of software, is carried out by healthy young males, who are used to dealing with healthy people in their workplace. Workplaces are a very different proposition from places such as medical centres, which by their very nature will deal with a high proportion of people who have assorted impairments.

With hindsight, issues like these are fairly obvious. With foresight, though, they are easily missed.

This is where there are advantages in using a systematic framework to tackle the requirements gathering, so that you can identify key types of requirements. Within the compass rose model, for instance, one key type of requirement involves very common activities, where design should usually focus on making those activities as smooth and problem-free as possible. That may sound obvious, but a lot of common activities are easily overlooked precisely because they are so familiar.

An example is ���landing zone��� activity within a building; when people come in from outside, they often pause or stop just inside the building to close umbrellas, undo coats, work out where to go next, etc. When you start watching out for this activity, you see it everywhere; however, most people are unaware of it until it���s pointed out to them. I’ve blogged about this previously in more detail.

For a very readable and fascinatingly insightful detailed discussion of this topic, Paco Underhill���s book Why We Buy is well worth reading. It���s about his work as an anthropologist studying what people do when shopping. The ���landing zone��� is one of the things he noticed and described.

There are numerous approaches to systematic observation, ranging from very broad scale observation of how crowds behave, down to extremely detailed observation of how people perform small physical and mental tasks. I’ve blogged about this previously, describing how you can systematically observe and record activities using task analysis and timeline recording.

When you combine these approaches with representations such as schema theory and script theory, you soon start to identify long-term regularities in requirements at different levels of detail.

For instance, one common requirement for buildings such as medical centres involves transport. At a coarse grained level, there���s a requirement for somewhere to park visitors��� private vehicles. This requirement has been around since at least Roman times, and across a wide range of cultures. At a finer-grained level, however, there have been changes over time, with the schema for private vehicle changing from various types of coach or cart to various types of car. Many parts of the schema, though, have remained largely unchanged despite the changes in technology, such as the amount of space required for each vehicle, and the need to have the parking area close to the building.

I���ll return to this theme in more detail in a later article. Now, though, I���ll focus on another recurrent theme in requirements, namely sensory issues.

Waiting

The design of waiting rooms is another fine, rich area in terms of opportunities for getting it right or getting it hopelessly wrong.

I���ll focus on one issue involving a common task that interacts with sensory issues which tend to be overlooked in the design of waiting rooms. That issue is knowing when it���s your turn to see the doctor.

One obvious way of doing this is to use a visual method, such as a screen which announces that doctor X is ready to see patient Y, or a ticketing system. That works well if you happen to have reasonable eyesight, and you happen to be looking at the screen when the announcement is flashed up. Those are big assumptions, though, especially in a medical waiting room. A lot of the patients will by definition be in poor health, often with poor eyesight. A fair number of patients will be young children, so the parent or carer with them will have to divide their attention between keeping an eye on the child and keeping an eye on the screen to see if it���s the child���s turn.

Overall, this is a regular source of stress, especially if patients don���t know what happens if they miss their name being announced ��� will they miss their appointment completely, and have to come back on another day? The medical practice staff will know the answer to that question, but very few patients know it.

Another obvious way of letting patients know when it���s their turn is to use an auditory method, such as an intercom announcement that doctor X is ready to see patient Y. Again, this assumes that you have reasonable hearing, which by definition will often not be the case, and it assumes that you���re within earshot, which you might not be if you���ve had to go to the toilet (again, quite likely among patients needing to see a doctor). There���s often a lot of background noise as a further problem ��� for instance, other patients talking to each other, or children crying or playing, and muzak or a permanently-on TV.

A lot of these problems can be reduced via the design of the rooms and the choice of technology.

For instance, architects are fond of atria and light wells, which look dramatic, but which often play hell with acoustics. Architects are also fond of big open spaces, which again look dramatic, and which are often cheaper than spaces containing dividing walls, but which cause a lot of problems with noise levels. These also often cause problems in terms of the distance between a patient and the announcements screen.

Architects and medical practices are usually fond of smooth surfaces which can be easily cleaned ��� a big issue in a medical context ��� but again, these are often a problem in terms of noise, because they tend to reflect sounds rather than absorb them.

The other senses can also be a significant issue in a medical context. Some children on the autistic spectrum, for instance, are highly sensitive to smells; so are some pregnant women.

Sensory issues have been a constant feature of requirements for a long, long time; a good example is Classical Greek and Roman theatres, whose design deliberately incorporated very sophisticated acoustics. A lot of sensory-related requirements have remained pretty much unchanged for thousands of years, so it���s unfortunate that the designs of many modern buildings don���t make significant allowance for them.

Closing thoughts

In later articles, I���ll work through some cases in detail, showing how a building���s requirements can be handled cleanly and systematically. (I���d originally planned to do that in this article, but doing it in detail will require a fairly lengthy article, so I���ve concentrated on the overview this time.)

The take home message from this article is that if you use a combination of the compass rose model and of systematic requirements gathering via the methods described on this blog, you can quickly identify key requirements that are likely to remain unchanged for the expected lifetime of the building, even if other requirements change. A lot of those long-duration requirements involve clusters of activities that are so common that people don���t give them a second thought; however, it���s precisely because they���re so common that it���s important to incorporate them as smoothly as possible into the design.

In terms of sensory issues, I���ve focused in this article on the senses of the people using the building. However, it���s very tempting to speculate about sensory issues and architects. A lot of architecture looks more like monumental sculpture than like a construction designed to facilitate human activities. Many skyscrapers are more like machines for looking at than machines for living in or for working in, to rehash a famous architectural quote. There���s a strong visual element in those designs, to the exclusion of other important senses, and to the exclusion of many aspects of functionality.

I have no objection to buildings looking striking and beautiful; quite the contrary. However, I have strong opinions about buildings that impose needless difficulties on the users because an architect wanted to build a really big sculpture.

In the next article in this series, I���ll pull together the various themes so far, and consider what we can infer about people���s dream lives, and what we can do about any knowledge we gain from this.

Notes and links

Sources of images in the banner:

“Out-patients’ Waiting hall. Western Infirmary. Wellcome L0000310″ by http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obf_images/9b/b9/363a1088d7d0b30228dcea2e7a10.jpgGallery: http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0000310.html. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Out-patients%27_Waiting_hall._Western_Infirmary._Wellcome_L0000310.jpg#/media/File:Out-patients%27_Waiting_hall._Western_Infirmary._Wellcome_L0000310.jpg

“DworzecPKP Miedzylesie wnetrze” by Krystian Kuchta – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DworzecPKP_Miedzylesie_wnetrze.jpg#/media/File:DworzecPKP_Miedzylesie_wnetrze.jpg

There���s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D���Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

April 11, 2015

People in architectural drawings, part 4; complicating factors

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the fourth in a short series about finding out what people would really like in life, using architectural drawings and fantasy buildings as a starting point.

The first article discussed how if you show people a range of possibilities, including possibilities that they would probably never have thought of, then their preferences can change dramatically from what they would initially have told you in an interview or questionnaire.

The second article looked at regularities in people���s preferences; the mathematics of desire, applied to buildings.

The third article examined changes in preferences and in fashions over time; it also examined the issue of practicality, and how practicality could change over time as a particular technology becomes obsolescent.

In today���s article, I���ll look at some complicating factors which need to be kept in mind when examining this area. For instance, why does the sun always shine in architects��� drawings? There are sensible reasons, and they aren���t just about optimism���

Sunshine and rain: Two scenes from Japan

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article; first image slightly cropped to fit.

Sources of original images are given at the end of this article; first image slightly cropped to fit.

Visibility

One good reason for showing scenes in sunshine is visibility. This is particularly important if you���re using the image to convey practical information, as opposed to producing a work of art. The brighter the lighting, the easier it is for the viewer to see what���s going on.

The same principle applies in the opposite direction in reconstructions of archaeological scenes. Many of those scenes are chiaroscuro, i.e. a mixture of brightness and shadow. This is because conscientious artists don���t want to include anything in the image which is just guesswork, rather than evidence-based, so they obscure any uncertain parts of the scene with strategically placed shadows, smoke and clouds.

Resolution and options on the imaging software

As usual with any technology, the software and hardware you���re using to produce an image of a building will at best nudge you in directions you might not want, and at worst will actively get in your way.

Software is likely to make surfaces, including grass, look very homogenous and very clean, without any of the blemishes brought by time and weather and wear and tear. This is particularly noticeable in real buildings where surfaces that were once gleaming white are now stained and dingy.

Software will also nudge the user towards including a few standard images of people in the scene, from near the top of the menu of standard images. Those images probably won���t include children running around, or people in wheelchairs, or skateboarders, or people selling copies of the Big Issue. Including diversity will probably take a little more effort, and will probably be an early casualty of tight deadlines and budgets.

This isn���t just an issue of social inclusion. A building needs to work for the range of likely users and activities it���s intended to support. Different groups of users, such as people in wheelchairs, will each have their own requirements and preferences; omitting them from the illustrations makes it that bit more likely that they���ll be forgotten in the general design process.

Time taken to think through the detail

When you���re producing a working model or a working diagram, you���re often working against a deadline and/or a budget. The more detail you put in, the longer the artwork will take, and the more it will cost. This will nudge you towards producing a model or image that shows the main features, but doesn���t include what you consider to be the minor details.

One problem is that your idea of what constitutes a minor detail may be very different from the client���s opinion and/or the end user���s opinion, not to mention other the opinions of other stakeholders such as the health and safety people.

Sometimes those details will be a matter of aesthetics and personal preferences; sometimes, though, they���ll be very functional and practical. The risk for the designer is that the client will view this detail as symptomatic; if you���ve got this detail wrong, what else have you got wrong as well?

The averaged faces principle

Another side effect of images that don���t show fine detail is that they may be perceived as more attractive because of the lack of blemishes. An obvious example of this principle is images of celebrities whose skin blemishes have been smoothed out with Photoshop.

This has been widely assumed to be because younger faces tend to have smoother skin, and because youthful appearance is perceived as more attractive than older appearance. However, there may be another effect involved as well, or even instead.

There���s been a fair amount of research over the years into perceptions of faces. One strand of this research involves averaged faces, where several photos are superimposed on each other to produce an average face.

The title of one paper from this research sums up one key finding elegantly: Averaged faces are attractive, but very attractive faces are not average. (Alley & Cunningham, 1991)

Why are averaged faces attractive? Nobody really knows. One possible explanation is that averaged faces look familiar, and familiar objects tend to be perceived as more attractive, if other things are equal. Another possible explanation is that they have fewer distinctive features, because those features have been diluted away in the averaging process. This could make them more attractive because they require less mental processing than more detailed images.

There���s a sporting chance that the same principle applies to images of buildings, where slightly fuzzy images without much fine-grained detail could be perceived as more attractive because they require less mental processing.

Closing thoughts

People who produce images of building designs are nudged by technology towards producing images which look like a cross between a tourism brochure and something from the Stepford Wives. The images they produce will tend to omit detail, and will tend to be bright and clean.

That���s a problem, for various reasons. One reason is that the image is subtly misleading, in the direction of optimism rather than realistic identification of key issues, and away from the direction of social inclusion. Another is that the image shows the best case for that building; it doesn���t show how the building���s design will work in rain or snow or gales, for instance.

In the next article in this series, I���ll look at ways of identifying common user activities and requirements that should be incorporated into the design process, and that can be handled cheaply and simply, producing significantly better designs as a result.

Notes and links

Sources of images in the banner:

“Kinkaku3402CB”. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kinkaku3402CB.jpg#/media/File:Kinkaku3402CB.jpg

There���s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D���Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

April 3, 2015

People in architectural drawings, part 3; requirements, obsolescence and fashions

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the third in a short series about finding out what people would really like in life, by looking at images of dream buildings.

In the first article, I looked at why the obvious approach doesn���t work very well. If you just ask people what they want, you tend to get either no answer, because people don���t know, or to get low-aspiration responses, for various reasons that are well known in requirements acquisition research. If, however, you instead show people a range of possibilities, including possibilities that they would probably never have thought of, then their preferences can change dramatically.

So, in this series I���m looking at fantasy and concept art images of buildings, which explore as broad a range of possibilities as the artists and architects can imagine. I���m looking at them to see what regularities emerge within those dream buildings; what sort of world do the creators of those images, and the people who like those images, desire?

In the second article, I looked at how human biases affect our aesthetic preferences. I concluded that a lot of people like really, really big buildings. Those buildings look awe-inspiring, but when you stop to think about details like how anyone is going to clean the windows, you start to realise that maybe those buildings aren���t terribly practical. However, how can you tell what will be practical within the lifetime of a building, when the available technology and the functions of the building are likely to change? There���s the related risk that tastes will change, and that today���s beautiful building will become tomorrow���s eyesore.

In this article, the third in the series, I���ll look at the issue of practicality versus obsolescence, and at changes in fashion.

Thinking big, in fantasy and reality

Thomas Cole, the Titan���s Goblet, and a Vauban fortification; full image credits at the end of this article

I���ll start with an extended quote from Vitruvius, the classical Roman architect, which neatly illustrates two major issues in architecture and lifestyle.

The quote starts with a classical Greek architect meeting Alexander the Great.

His strange appearance made the people turn round, and this led Alexander to look at him. In astonishment he gave orders to make way for him to draw near, and asked who he was. “Dinocrates,” quoth he, “a Macedonian architect, who brings thee ideas and designs worthy of thy renown. I have made a design for the shaping of Mount Athos into the statue of a man, in whose left hand I have represented a very spacious fortified city, and in his right a bowl to receive the water of all the streams which are in that mountain, so that it may pour from the bowl into the sea.”

Alexander, delighted with the idea of his design, immediately inquired whether there were any fields in the neighbourhood that could maintain the city in corn. On finding that this was impossible without transport from beyond the sea, “Dinocrates,” quoth he, “I appreciate your design as excellent in composition, and I am delighted with it, but I apprehend that anybody who should found a city in that spot would be censured for bad judgement. For as a newborn babe cannot be nourished without the nurse’s milk, nor conducted to the approaches that lead to growth in life, so a city cannot thrive without fields and the fruits thereof pouring into its walls, nor have a large population without plenty of food, nor maintain its population without a supply of it.���

Vitruvius, The Ten Books On Architecture, Harvard University Press edition, 1914; Translation by M.H. Morgan (from Project Gutenberg).

This story may well have been the inspiration for the first image in the banner, Cole���s painting ���The Titan���s Goblet���. The goblet is huge ��� it has boats sailing on its waters, and a temple on its rim. It���s also a bit limited as regards the practical side of life.

The second image in the banner also shows a huge construction, although its sheer size isn���t obvious until you start looking closely, and realise that the woods in the bottom left of the picture are also part of the structure. It���s a classic fortification by Vauban, the leading military architect of the eighteenth century. It���s designed rigorously and thoroughly, with every feature serving a carefully designed purpose. The triangular motif repeated throughout the design is used to make sure that every inch of the approaches to the central fort is covered by at least one cannon. There���s nowhere that attackers can take cover.

Building for the future: The problem of unexpected obsolescence

So, how well did these two approaches stand up to the test of time? Alexander���s very practical points about infrastructure are still valid today. Vauban���s equally practical points about military design were soon made obsolete by changes in military technology.

Architects are well aware that today���s brilliant design may be tomorrow���s quaint historical curiosity, so they���re understandably wary about getting too far involved in designing buildings for specific purposes. It���s not just massive military designs that can become outmoded overnight. At a humbler level, a good example is the threshing barn. This was a key feature of farms for centuries; it���s a barn with a pair of huge doorways opposite each other, to allow a through breeze. Farm workers would thresh the grain in that breeze, safe from rain that would spoil the grain, with the through breeze blowing away the chaff from the grain during the threshing. Then, in the nineteenth century, new inventions in agricultural machinery made the threshing barn pretty much obsolete.

However, ���pretty much obsolete��� is a very different proposition from ���obsolete���. It���s a crucial distinction, which I���ll explore in the next section.

Obsolescence, survival and building for the future

When you start looking closely at changes in technology, you notice that old technologies can keep going for a surprisingly long time. It���s not just because of die-hard traditionalists keeping something going for its own sake. Often, what happens is that a new technology takes over most of the roles once occupied by the old technology, but not all of those roles.

For example, the invention of the escalator didn���t mean that architects stopped using stairs, and the invention of email didn���t mean the end of the telephone. A lot of the features of a modern office are pretty much the same as those in an office from Roman times: desks and chairs and lights and document storage. The modern features may look a bit different from their Roman equivalents, but their functions are very similar.

Similarly, in architecture, a lot of the features of buildings have remained more or less constant across time. If you���re planning a large public building, for instance, then access and exit routes and times are important; you want people to get in and out with the minimum of delay. The Roman Coliseum compares favourably to the best modern stadia in this respect.

So, although an individual building may be used for different purposes across time, and some of those purposes will entail different requirements, that doesn���t mean that we need to give up and say that there���s no point in looking at user requirements for a building. A lot of requirements will remain the same across a wide range of new uses; also, anyone with any sense will check that the proposed new use for a building fits reasonably well with the features already built into it. Old threshing barns usually weren���t torn down; instead, they continued to be used. The ends of the threshing barn were originally used for storage; they could still be used for that purpose after the change in threshing technology. There were plenty of other ways that the central area between the two doors could be used. The ���threshing��� part of the building���s role may have become obsolete, but the building as a whole was very much fit for most of its other original purposes, and the two huge doorways offered a lot of affordances for new uses.

I���ve already written about regularities in how people use space, such as the ���landing zone��� within a building entrance when people come in from the street. Exactly the same approach can be used to identify and design for other regularities in human behaviour, so that a building���s form mirrors the function and makes life easier for the humans using it.

What about the argument that fashions and tastes change unpredictably? That holds some truth, but again, there are longer-term regularities if you know where to look for them.

Society and technology

Fashions and tastes have been studied extensively by sociologists and sociolinguists and social anthropologists, among others. What they���ve found repeatedly is that power and access to limited resources are both deeply involved in most manifestations of fashion and ���good taste���.

One very visible example: In most societies up till very recently, having a suntan was an indicator of doing a manual, low-prestige job; the elite were careful to keep their skins as pale as possible, to demonstrate that they did not have to do physical work.

That changed with the Industrial Revolution, when large populations of urban manual workers had indoor jobs, out of the sun, so the elite acquired suntans to show that they didn���t need to work indoors.

There���s a similar dynamic about the accents and dialects of the different groups. When society consists of rural peasants and urban elites, then the rural accents are usually perceived by the elite as rough and ugly. When society consists of rural peasants, urban factory workers and elites, then the urban factory workers��� accents are perceived as ugly, and the peasants��� accents are perceived as quaint and unspoilt.

You get much the same with perceptions of nature. Until the Industrial Revolution, nature was generally viewed in terms of threatening wilderness and wasteland. After the Industrial Revolution got under way, nature started to be viewed as something beautiful and idyllic. There���s a fascinating account of this in Man and the Natural World, which looks at changing attitudes towards nature across the years 1500-1800.

Closing thoughts

So, if you know what to look for, you can identify a fair number of practical requirements that are likely to remain unchanged for a long time ahead, and a have a fair shot at predicting what changes in people���s tastes are likely to occur.

In a later article in this series, I���ll look at how you can identify those long-lasting requirements. First, though, I���ll look at potential pitfalls in trying to identify people���s dream lifestyles from their preferences in pictures of fantasy houses and fantasy worlds; that will be the topic of the next article in this series.

Notes and links

There���s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D���Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of images in the banner:

“Neuf-Brisach 007 850″ by Luftfahrer at the German language Wikipedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neuf-Brisach_007_850.jpg#/media/File:Neuf-Brisach_007_850.jpg

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

March 28, 2015

People in architectural drawings, part 2; the mathematics of desire

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the second in a short series about finding out what people would really like in life.

The obvious approach doesn���t work very well. If you just ask people what they want, you tend to get either no answer, because people don���t know, or to get low-aspiration responses, for various reasons that are well known in requirements acquisition research.

If, however, you instead show people a range of possibilities, including possibilities that they would probably never have thought of, then their preferences can change dramatically.

This series is about showing people a range of possibilities via images of buildings, which are intimately linked with a lot of other lifestyle choices.

In the first article, I looked at artistic representations of future and fantasy buildings, to see what trends emerged there, and what they could tell us about people���s desires. One trend that emerged strongly was for those buildings to be awe-inspiring, with lofty towers and huge portals.

This, however, raises one of those issues which are so familiar that we seldom think about them. Why are lofty towers and huge portals awe-inspiring in the first place, given that they can be wildly impractical?

Part of the explanation involves human cognitive biases and human preferences, which are the subject of this article.

In this article, I���ll look at those topics, and look at their implications for competition and change, with particular reference to concepts and literatures that give deeper insights into what���s going on.

From humility to hubris: Doors and desires

The mathematics of desire

I���ve written previously about regularities in what people tend to like. In some cases, more is better, with no upper limit. This is the superstimulus effect, which occurs throughout the animal kingdom.

In some cases, though, there people appear to prefer things that are a particular distance from the statistical mean average. For example, there���s a solid body of evidence that being tall brings more status and wealth, but that being very tall doesn���t. Translating that into statistical terms, the optimal height for status and wealth is somewhere between one and two standard deviations from the mean. There are similar figures for features such as the preferred ratio of leg length to torso length.

So which types of preference occur where? In the tables below, I���ve listed some common patterns in people���s preferences. I���ve given these patterns names from popular culture which make the underlying point clearly.

The first set of preferences are based primarily on social factors, rather than on the products involved (e.g. buildings or cars or whatever).

Social factors

The list below shows some common social factors in preferences:

“There can only be one”

“In with the in crowd”

“Bigger than yours”

“Blending in with the crowd”

“Humble”

���There can only be one��� involves having something that is in some way better than what everyone else has; for instance, the biggest house in the street, or the most expensive car. This is a recipe for competition; in the case of buildings, there is competition among architects to build the tallest skyscraper. The significance of this should become clear later in this article.

���In with the in crowd��� involves having something that marks membership of a prestigious group; for instance, having a house with over a million, or owning a Rolls-Royce. This is different from ���there can only be one��� since the prestigious group will usually have multiple members, whereas by definition the ���there can only be one��� set can only contain one member.

���Bigger than yours��� is what you might expect; it���s a purely comparative assessment, relative to the other person involved. This is another recipe for competition.

���Blending in with the crowd��� is a common strategy. It involves appearing average, and not being a ���tall poppy���.

���Humble��� is a strategy that can occur for various reasons. Sometimes it involves choosing to be below average on one criterion in order to be above average on another criterion (for instance, ascetics who have as few possessions as possible, in order to have as much spiritual purity as possible). Sometimes, the reason is an extension of ���blending in with the crowd���. In many parts of the world, for instance, house owners deliberately let the exterior of their house look shabby and dilapidated, because this will reduce the risk of criminals or tax inspectors deciding that their house is worth closer investigation.

That���s one way of looking at preferences. Here���s another, this time centred on the products themselves, rather than on what other people are doing.

Product-centred preferences

The list below shows some common product-centred preferences.

“As much as possible”

“Criterion-based”

“Two SDs above the product mean”

“Average”

“Minimalist”

���As much as possible��� is what it sounds like; for instance, the fastest car that can be bought. This approach is different from ���there can only be one��� because the focus is on the product itself, not on whether anyone else has that product.

���Criterion-based��� can take various forms. One example is brand-based preference; for instance, buying Apple products. Another example is the trophy, where there is a clear objective criterion for what constitutes a trophy (e.g. the weight of the fish in angling, or the height of a mountain in Munro-bagging, which involves climbing Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet tall.)

���Two SDs above the product mean��� is the equivalent of ���a fast car, but not a very fast car���.

���Average��� is what it sounds like (with the usual statistical caveat about there being three different ways of defining ���average���).

���Minimalist��� is what it sounds like.

There���s also a third way of categorising preferences, which is based on how to choose the product.

Methods for choice

There���s a classic distinction here, from Herb Simon���s work on decision theory. It���s between optimising and satisficing (sic; probably a combination of satisfying and sufficing).

Optimising involves finding the best product (or process, or whatever) for the task in question. Usually, this concept is used when there are two or more criteria for defining what is ���best��� and you have to juggle one criterion against the others (for instance, balancing cost against quality). Although this looks like the obvious best approach to use, reality isn���t that simple. Often, there aren���t any solid objective ways of deciding which criteria really matter, so your choices end up being quite subjective. Another problem is that gathering all the information you need can take a lot of time and effort.

Satisficing also involves juggling two or more criteria, but instead of trying to find the best solution, satisficing involves finding a good-enough solution. Usually you decide in advance what you will consider to be good enough. The great advantage of satisficing is that it���s quick; you simply choose the first product you find that meets your criteria.

Discussion

So, what are the implications for trying to identify and to build people���s dream lifestyle?

Social factors in people���s preferences have far-reaching implications. Several of the preferences, such as ���bigger than yours��� make the issue inherently unstable. No matter how big or expensive the average house is, for instance, ���bigger than yours��� players will always want their house to be bigger and more expensive than the next person���s.

This doesn���t necessarily mean that sustainable lifestyles are inherently impossible because of human competition. There are various ways of handling the inherent instability, as outlined below.

One useful literature in this context is game theory, which I���ve described in a previous article. A related literature deals with systems theory, which I���ve also described in a previous article. The two approaches complement each other neatly, and they provide a rigorous, powerful set of methods for understanding competition and the ripple effects from the competition.

Another useful approach is Transactional Analysis (TA), developed by Eric Berne, and described in fascinating, very readable books such as ���Games People Play���. The ���games��� in the title are actually strategies, such as the ���bigger than yours��� strategy described above. TA looks at these strategies in depth, including analysis of what happens when a strategy becomes pathological and of what can be done about it.

In addition, laws are an effective way of fixing the limits to competition; for instance, planning regulations. If there are fixed limits to how big a house can be, then ���bigger than yours��� players can either limit themselves to buying a bigger house from within the existing housing stock, or can shift their competition to some other topic of comparison.

Product-centred and choice-centred factors have a very different set of implications from social factors. They take us into topics such as client requirements and task analysis, which will be the topic of a later article in this series.

Both of those topics have an uneasy role within architecture. They are clearly important, and they play a part in some of the legislation and regulations within which architects have to work. However, architects are well aware that within the planned lifetime of a building, technology and tastes may change dramatically. A classic example is nineteenth century architecture designed with horses and carriages in mind. Architects understandably don���t want to spend a lot of time and effort on finding ways to fit within constraints that might no longer be relevant within a few years.

It���s an understandable feeling, but it���s a simplification. In the next article, I���ll look at design constraints and at changing tastes. They are fine, rich topics, that will take us into areas such as classic military architecture, categorisation of barns, and the role of pointy sticks in modern life.

Notes and links

You���re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they���re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There���s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D���Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Allusions within strategy names:

���There can only be one:

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091203/

���In with the in crowd���:

http://www.amazon.com/Another-Time-Place-BRYAN-FERRY/dp/B00002DEBB

���Hard to be humble���:

Related articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/05/03/the-compass-rose-model-for-requirements-gathering/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/finding-out-what-people-want-in-a-nutshell/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/09/05/client-requirements-the-shape-of-the-elephant-part-1/

Overviews of the articles on this blog:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/the-knowledge-modelling-book/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/150-posts-and-counting/

March 20, 2015

People’s dream buildings, part 1

By Gordon Rugg

This article is the first in a short series about what people would like their dream world to be like. Finding out what people would really like isn’t a simple matter of asking them. Most people only know about a limited number of possibilities, so their dreams tend to be correspondingly limited. When you introduce them to new possibilities, their dreams usually change dramatically, in scope and nature and aspiration. That’s what I’m exploring in this series of articles.

One way of introducing people to what’s possible is to show them pictures. The pictures don’t need to be of real scenes; often, the most interesting possibilities are the ones that are completely feasible, but that haven’t been built yet. So, one place to start is with images of imaginary scenes, in the form of fantasy landscapes and of architect’s drawings. In this article, I’ll look at common features in those scenes, to see what they tell us about those dream worlds. Some of the answers are surprising.

I envy the people in architect’s drawings and in the happier type of fantasy world (I’ll look at dystopias some other time). Their world is sunny and pleasant, full of contented people walking and standing elegantly in broad, inspiring plazas, in front of tall, impressive buildings that are clearly destined to win architectural awards. It’s a world where nobody gets caught in the rain, a world without graffiti or grime or the hassles of trying to negotiate a buggy and two small children through a narrow shop doorway in a crowded street.

It would be easy, and unkind, to write a humorous article on this theme. The full story is a lot more interesting, and has deep implications for how we think about the design both of buildings and of the human systems within which those buildings are located. It’s a story of the mathematics of desire, and of physical constraints, and of why we can’t know what we really want until we see it, and of what we can do about building this knowledge into the design process.

The easy targets

I’ll start with fantasy cities. Fantasy cities were not designed with bicycles in mind. Most sword and sorcery cities appear to have been designed by someone who saw a near-vertical hillside and thought: “Now that’s what I call a place to build a city”. Most high-tech ones feature superhighways and/or aircraft flying between the kilometre-high skyscrapers. Either way, if you’re on a bicycle, you’re not going to have a good day. The same goes for anyone with a wheelchair, or with a buggy plus a child or two, or with dodgy knees.

The buildings within those cities aren’t usually much better, when you start to think about the logistics of getting the shopping home, or doing the school run, or getting up the stairs with the shopping. They’re seriously big buildings. There’s an entire fascinating genre of fantasy paintings involving enormous doorways as the main feature, where the size of the building that goes with the doorway doesn’t bear thinking about.

Here’s an example. I’ve taken an arbitrary example of a doorway from that genre, and superimposed some indicators of scale over the doorway’s octagonal outline. (I got the approximate scale from some people in the foreground of the original painting; I’ve included a human silhouette of the same size in the bottom right of the doorway.)

It’s quite a doorway. You could set up Cleopatra’s Needle in it, with the Temple of Hephaistos alongside, and still have room for people to pass by. If you felt so inclined, you could fly a Learjet through it. Quite why you’d need a doorway that size is another question, but clearly there’s a good reason, since you see numerous similar-sized doorways, complete with doors to fit them, both in low-tech and high-tech fantasy worlds. As for the practicalities of repainting those doors when they get a bit tatty, or polishing the doorknob, or what happens when you lose the key, the mind starts to boggle.

In case you’re wondering about real-world doorways and gateways that were designed to impress, yes, there are some pretty impressive ones around, but when you look at them closely, you notice that most of the architecture acts as a big frame for a quite modestly sized space. How modest? Well, when Pompey the Great decided to have an elephant pull his chariot during his triumphal procession through ancient Rome, his plan went wrong because the elephant wouldn’t fit through the gateway into the city, much to the amusement of his political rivals. That’s the main triumphal gateway into the biggest city of the Western world at the time.

When you stop and think about it, having manageable-sized doors and gates makes a lot of sense from a practical viewpoint.