Gordon Rugg's Blog, page 13

October 16, 2014

Finding the right references, part 1

By Gordon Rugg

The best questions are often short.

In a comment on a recent article here, Mosaic of Minds asked which authors I’d recommend for further reading about Likert scales. It’s a fair, sensible question, which lifts the lid on a whole boxful of issues about academic references. Many of those issues are important, but not as widely known as they should be.

This article is the first in an informal series about academic references, online search, and the ways that evidence is used in research. In this article, I’ll be looking at two concepts that provide some useful structure for understanding this general area, namely craft skills versus formalised knowledge, and back versions versus front versions. I’ll start with an overview of these concepts, and then look at the insights they give into different sources of information, including academic references.

Craft skills

Craft skills in the traditional sense are what they sound like; practical, hands-on skills that operate where knowledge meets physical reality. Traditionally, academia had a somewhat snobbish attitude towards craft skills, viewing them as low-level sordid practicalia, very different from the high-status, highly abstract knowledge of Great Thinkers. (Even Great Thinkers, however, had to admit that craft skills were a good thing if the plumbing needed to be sorted out, or the roof was leaking.)

This divide was reflected in the structure of many education systems, which contained a major division between “practical” education and “academic” education. This distinction goes back a long, long time. Craft skills were taught via one set of institutions, such as apprenticeships or the old polytechnics in Britain; formalised academic knowledge was learnt at universities. Different countries used different names for the institutions, but the underlying distinction was widespread.

There was some overlap in content between the two sets of institutions, but the conceptual distinction was deep rooted, as anyone who has worked in a polytechnic turned university will know. The two have very different cultures, values and mindsets.

In more recent decades, researchers have started to realise that the world of formal academic research contains its own craft skills. Once you start investigating this concept as a researcher, you start seeing your own world in a fascinating new way. You get a fresh understanding of a lot of issues that have often been long established for good reasons, but where nobody ever explained to you what those reasons were. A lot of my work with Marian Petre about academic writing and academic reading comes from this approach.

More recently, I’ve been looking at ways of modelling knowledge systematically, tracing it from the most abstract concepts right down to where the ripple of connected concepts bumps into reality. I’ve blogged about it in previous articles:

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/02/27/what-are-craft-skills-a-brief-overview/

https://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/06/20/are-writing-skills-transferable

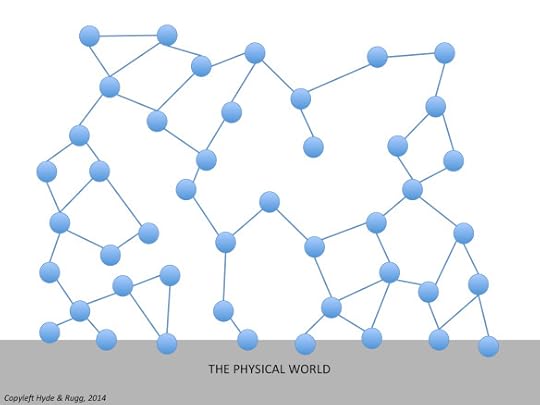

This work has produced some interesting ways of viewing the old distinction between craft skills and formalised knowledge. Here’s a pair of images showing the core idea schematically.

In the first image, above, the circles and lines are assertions, along the lines of “X is a type of Y” and “Y causes Z” and “A has attribute B”. At the bottom of the diagram, there are assertions that are linked directly to the physical world, such as “sulphur is usually yellow”. If someone asks what you mean by “sulphur” or “yellow” you can point at some physical examples; those examples are real and observable, even if the labels that we use to categorise the examples are intangible social constructs.

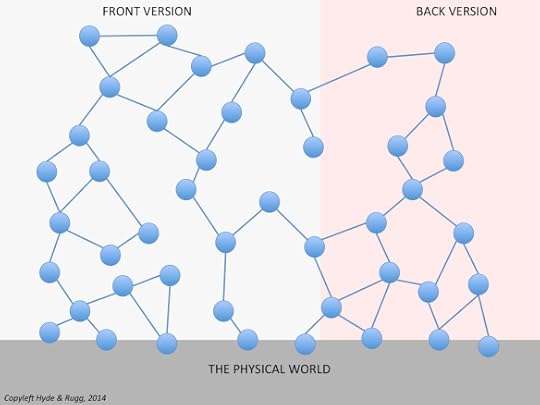

If you now represent this schematically, to show the distinction between craft skills and formalised academic knowledge, you get something like the second image, below.

The lowest level assertions are now in the category of “craft skills” and the highest level ones are in the category of “formalised knowledge”.

This visualisation shows the arbitrary nature of the distinction between the two categories. I’ve written before about craft skills, and about how the distinction is not a very helpful one; I argue that it’s more useful to think in terms of how solid the links are between an assertion and observable reality, and in terms of how many links there are between an assertion and observable reality.

When you look at formal academic disciplines from this viewpoint, you soon realise that some involve a great deal of knowledge that links directly to the real world. The physical sciences often involve a lot of field work which is as real as it gets; music and art can also involve a great deal of very specific hands-on knowledge about instruments and materials and processes. That’s very different from a field such as literary studies, where it’s possible to get a degree in the subject without learning anything about the physical process of producing a book or a newspaper.

That’s why I think that the concept of “craft skills” can have some use as a convenient shorthand term, but doesn’t hold together very well if you try to use it more rigorously. For more rigorous use, I prefer to use a representation like the first image, where I can see how many points of contact there are with the physical world within a discipline, and can see which concepts are covered within a particular module or course.

That’s a swift overview of craft skills; I’ll return to the topic later in this article.

Front and back versions

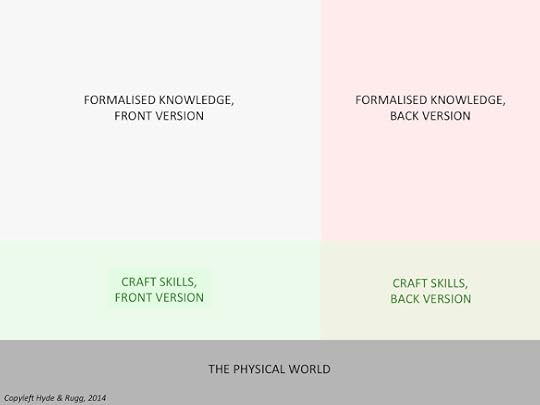

The next diagram shows the concept of front and back versions, applied to the same schematic set of knowledge.

A front version is the version that members a group will show to outsiders; the back version is the behind-the-scenes version that is only shown to group members. It’s a concept introduced by Goffman, who used the analogy of a theatre performance, where there’s the version that’s shown to the audience (the front version) and the backstage reality of performers rushing round changing costume, which is kept hidden from the audience. It’s a useful analogy because it makes the point that the back version isn’t necessarily being kept hidden because it’s shameful or illegal.

As with craft skills and formalised knowledge, this isn’t a clear-cut binary distinction; group membership often involves grey areas and degrees of membership.

That’s an overview of the two sets of concepts at the heart of this article.

What happens when we put them together, and see what light they throw on academic publications?

Applying these concepts to publications

We can represent these concepts as a two by two matrix, as in the image above. This immediately gives us a neat slot for formal academic articles, textbooks, etc; they contain front versions of formalised knowledge, explicitly intended to be available to anyone who wants to read them. It also gives us a neat slot in the bottom left of the matrix for practical manuals, which explain craft skills to anyone who wants to read them.

Those two are easy. What about the other two cells in the matrix, though? That’s where things start to get really interesting.

Like any other field, academia has front versions and back versions. Some back versions, such as the discussions in exam boards, are kept private for good legal reasons involving student confidentiality. Other back versions involve issues such as acceptable versus unacceptable shortcuts in research methodology, which are more about conventions and norms. Still other back versions involve scandals, potential scandals, and suspicions, ranging from mild personal disapproval to reports of criminal misbehaviour.

So how do these appear in publications, if at all?

There have been several high-profile cases over the years where high profile classic research findings have been called publicly into question. Examples include Burt’s work on IQ and Meade’s work on teenage sexual behaviour in Samoa. A common pattern is that there are suspicions in a research field about a particular set of findings for years, followed by published claims that there is evidence showing that the original data behind those findings shouldn’t be trusted. In some cases, there’s evidence that some or all of the original data had been fabricated; in others, there’s evidence of sloppiness or data manipulation by the researcher and/or by the research assistants carrying out the data collection; in others again, there’s evidence that the human participants gave misleading information to the researcher, either maliciously or as a joke or because of cultural norms about it being polite to tell people what they want to hear.

Some of these cases involve formalised academic knowledge (e.g. in cases of deliberate fraud); others involve craft skills in data collection and/or data analysis. That aspect of the two by two matrix holds up reasonably well.

The matrix doesn’t hold up so well in regard to that throwaway statement about “published claims”. If a claim is published in a journal or book that’s available for anyone to read, then it should count as a front version. That’s how a lot of re-assessments of debatable claims start out, as published academic articles, in the public domain. However, it can take years before those claims reach the non-specialist world.

In reality, there’s a huge difference between something being available for anyone to read, and anyone being able to read and understand it. Academic technical language is often effectively incomprehensible to outsiders because it’s dealing with concepts and terms that take years to learn. This means that we need to make a distinction between front versions that are actually understandable by non-specialists, and front versions that aren’t understandable by non-specialists.

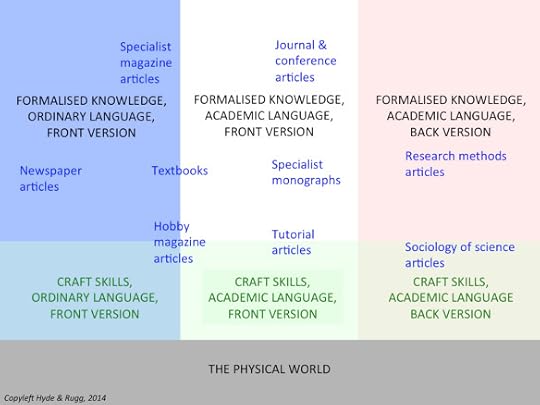

A three way model

This gives us a matrix with six cells. There’s one row for formalised knowledge and one row for craft skills. There’s one column for “plain English” front versions, plus a second column for “specialist English” front versions and a third column for back versions.

When we plot various types of publication on this matrix, it gives some useful insights.

This diagram looks complicated, but it’s actually quite simple if we go through it step by step.

Plain English front versions

On the left, we have the “plain English” front versions.

Some of these are completely accessible to non-specialists (e.g. newspaper articles). Some are quite specialist and deal with abstract knowledge, but are still intended for the general educated reader (e.g. popular science magazines). Some are quite specialist and focus on craft skills (e.g. specialist hobby magazines).

Academic language front versions

In the middle, we have the front versions that are written in specialist language. Specialist language ranges from fairly accessible to practically incomprehensible to non-specialists. Textbooks are usually on the “fairly accessible” side, whereas journal and conference articles are usually on the “practically incomprehensible” side.

I’ve included tutorial articles in this column, at the area of overlap between craft skills and formalised knowledge. Tutorial articles are invaluable if you’re trying to learn a new method to use in your research. They are what they sound like, namely articles that give you a tutorial on how to use a particular method. Although tutorial articles are invaluable, most students and new researchers have never heard of them.

I’ve also included specialist monographs in this column. These are similar to journal articles in that they’re intended for a readership of specialist researchers, but different from journal articles in that they’re a single publication. Usually, but not always, they’re a book. (For brevity, I won’t go into detail about the fine points of this.) Some are classic texts that every specialist in the relevant field will know well, and probably own; others will only ever be read by a handful of people (but might still be classic texts to that handful of people).

Academic language back versions

I’ve treated this column differently from the other two. The types of publication I’ve cited are publications about the back version of research, rather than publications that are the back version of research. I’ve done this because most readers of this article will find those publications more useful and/or thought provoking than the others. (If you’re wondering about what would count as publications that are the back version of research, then examples include original field notes and personal notebooks, which are often legally required to be kept confidential.)

There’s been a quiet growth over recent decades in research into how research is actually conducted. The sociology of science and the history of science are both well-established research fields, and are usually involved in heated debates about assorted topics. Some of these debates are about highly formalised meta-knowledge; examples range from postmodernism to the debate between frequentist and probabilist models in statistics. Others go deep into the craft skills level, such as debates about the role of local interpreters and guides in what anthropologists get to hear from local people.

If you’re considering a career in research, or you’re a new researcher, it’s well worth dipping into these literatures; they give a useful grounding in the realities on which research is based, and on the questions that arise from those realities.

Concluding thoughts

Returning to the question at the beginning of this article, if you’re looking for references on a topic, then the answer to a “what would you recommend?” question is: “It depends”.

That might sound unhelpful, but it’s actually helping the person asking the question to refine their understanding, and to plan their reading more efficiently.

For instance, if you’re completely new to the concept of Likert scales, then the best place to start will be at the left of the diagram above, with plain English versions. The advice that I usually give students in this situation is to find a textbook that has a writing style they’re comfortable with, and that has a chapter on the topic. The reasoning behind this is that textbooks are usually a fairly trustworthy source for an overview, and that a chapter will usually be short and simple enough to be easily understandable; an entire textbook on Likert scales will probably drown the average reader in detail.

If you’re writing about previous good examples of using Likert scales, then you’ll want to track down some classic journal articles on the topic (I’ll be writing about how to do this in a separate article).

If you want some tips on the low-level practical issues involved in using Likert scales, then a tutorial article is a good place to start.

If you’re wanting to pick up some marks for showing a deeper critical understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of Likert scales, then you’ll need to go into the literature in the rightmost column, including the theoretical literature on research methods (e.g. issues involving psychophysics and measurement theory in relation to Likert scales) and the craft skills literature on research realities (e.g. whether some cultures believe that it’s polite to respond in a particular way to Likert scales).

So, in conclusion, a good, clear, short question led into a long answer. So it goes, sometimes. I hope that you’ve found this useful; I’ll be writing about other aspects of literature, references and search in later articles.

Notes

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book, Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

My books with Marian Petre:

A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Unwritten-Rules-Research-Study-Skills/dp/0335237029/ref=dp_ob_image_bk

October 9, 2014

Likert scales and questionnaires

By Gordon Rugg

I really, really, really hate badly designed questionnaires.

That’s an issue, because most questionnaires are badly designed. The bad design makes them worse than useless. At least if something is useless, it isn’t making the situation actively worse. Badly designed questionnaires, however, can make a situation significantly worse, by adding disinformation into the story, so that a problem takes longer to solve.

This is even more of an issue because questionnaires are so widely used. Any idiot can design a bad questionnaire, and many idiots do, with a variety of excuses, such as:

Every other idiot is doing this, so I want to get in on the act

Nobody ever got fired for using a questionnaire

It’ll all come right in the end anyway, even if I do it badly

Who cares?

None of these arguments inspire much confidence or respect with regard to the person using them.

In this article, I’ll make a start on the issues affecting questionnaires. They’re big issues, that have deep roots and broad implications, so discussing them in full will take a number of articles. For now, I’ll focus on a single topic, namely how Likert scales can be used within questionnaires.

Likert scales, and Likert-style scales, are widely used (and widely misused) in questionnaires. In this article, I’ll look at some of the key concepts involved, and at some of the issues involved in using this approach properly.

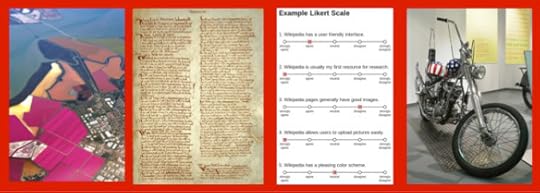

Images from Wikipedia; sources at the end of this article

I’ll start by giving some background context about problems with questionnaires.

Questionnaires have been in use since at least the days of the ancient Romans. If someone’s using a questionnaire today, you might expect that they’ll be at least as professional about it as someone working before electricity was discovered or Columbus encountered America. The reality, though, is very different.

Here’s an example of getting it right. It’s from the Domesday Book, compiled in 1086.

There is situated there, in addition, one berewick, as the manor of Heuseda. In the time of king Edward, 1 carucate of land; then and afterwards 7 villains, now 5. At all times 12 bordars, and 3 serfs, and 40 acres of meadow; 1 mill. Woods for 16 swine and 1 salt pond and a half.

http://www.fordham.edu/Halsall/source/domesday1.asp

A key point about this particular entry is that it records the ownership of one and a half salt ponds.

How can someone own one and a half ponds? When you stop and think about it, you realise that it’s perfectly reasonable; the second pond can be jointly owned by two people.

The team that compiled the Domesday Book got this right, over nine centuries ago. Most present-day questionnaires don’t get it right.

I use this example regularly with my long-suffering students. One common response is along the lines of “Okay, but how often is that going to happen?”

It’s a fair question, and the first part of the answer is that I don’t know. The second, and much more important, part of the answer, is that the person giving that response doesn’t know either. We might guess that it’s a rare issue, but the key point is that we would both be guessing. That’s not a good strategy, especially when the whole point of your questionnaire is to find out how often something actually occurs.

There are a couple of similar questions where I do know the answers, and where the answers show why this issue is really important. One is the question of how many motorbikes you own; the other is the question of whether a new-born baby is male or female. In both cases, the answer “not sure” occurs about 1% of the time.

In the case of motorbike ownership, there are numerous possible reasons for not being sure whether or not you own a motorbike. As with the half-pond, you might own one jointly with someone else; does that count as owning it? Another possible situation is where you are buying it in instalments, but haven’t completely paid it off yet. Another is that you own an engine-supplemented pushbike; does that count as a motorbike or not?

The figure for motorbike ownership comes from a newspaper report that I saw years ago. The precise figure doesn’t particularly matter; the more important issue is that this illustrates how an apparently simple question can have multiple possible answers that are only obvious with hindsight.

The figure for baby gender similarly varies depending on the definition that you use. Most of the numbers that I’ve seen are in that general area. A lot of babies are born with ambiguous or unclear gender. One per cent may not sound a lot when expressed as a percentage, but when you work it out as a percentage of the population, then you realise that the hospital system for the UK will be dealing with about ten thousand cases a year, as a back-of-envelope figure. That’s a lot of cases, and all of them are going to involve major human issues, as the parents grapple with decisions that will have huge implications for the child’s life, and that they have probably never thought about before, and where building some compassion and support into the medical system can make an enormous difference to everyone involved.

So, it’s really important to find out the frequency of the answers that aren’t immediately obvious. Even if they’re only 1% of the population, in some situations that can translate into a major issue. Sometimes, conversely, you find that something is much more widespread than you had imagined. The early surveys into human sexual behaviour turned up quite a few answers that hardly anyone had been expecting, and that changed the landscape for debate about which sexual behaviours should be decriminalised.

All the examples above involve things that are solid and tangible; there’s not much doubt about whether or not a motorbike exists when it’s right in front of you, or about whether a salt pond exists if you’re standing in it. However, even with those items, there’s a surprising amount of uncertainty; for instance, is that machine in front of you actually a motorbike as opposed to a scooter, or is the water you’re standing in really a salt pond as opposed to a lagoon?

If the situation is that messy with relation to motorbikes and ponds, then you’d expect things to be even worse with relation to subjective issues such as emotions and opinions. That’s where Likert scales enter the story.

Likert scales

Likert scales are named after Rensis Likert, who invented them in the early 1930s.

They turn up in most questionnaires, usually in the form of response options such as:

Strongly agree

Weakly agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Weakly disagree

Strongly disagree

That’s a really useful format for handling responses about subjective, intangible topics.

So far, so good.

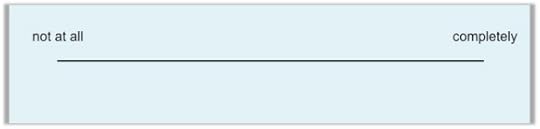

Another variant is the visual analogue Likert-style scale. This occurs in various forms. Here’s one form, from Wikipedia:

Here’s another form, where the participant draws a vertical line through the horizontal scale line at the point of their choice.

The initial line has a label at each end, like this.

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

The participant now draws a vertical line (shown below in blue) at the appropriate point on the horizontal line.

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

The researcher measures the distance along the horizontal line to where the vertical line is placed; that gives a score. In the example below, that score would be 78.

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

Usually these scales are 100 mm long, so the researcher can get a value anywhere from 0 to 100, meaning that the researcher can use much more powerful statistics on the data (and use much smaller sample sizes) than would be the case with a five point scale like the one in the Wikipedia example above.

I’ve written about this approach in more depth here:

Analysis

Likert scales and Likert-style scales look straightforward, and at one level they are, right up to the point where you start to analyse the results. At that point, the grim reaper of Statistics winnows out the wheat of virtuous research from the chaff of clueless, uninformed amateurism. It’s not a pretty sight.

If you’re doing your analysis right, you’ll be able to give confident, well-informed answers to questions such as:

What’s the difference between a Likert scale and a Likert item?

Are you assuming that your data are on an interval scale or some other scale?

What allowance have you made for acquiescence bias?

How have you checked for external validity in your data?

What allowance have you made for Miller’s findings on cognitive limitations in your choice of number of response options?

What level of skewness is present in your data?

What level of kurtosis is present in your data?

Which statistical test will you use to check for statistical significance in your data?

Which policies will you change in which direction if you find which results in your data?

There are plenty of other, similar, questions where those came from. If you don’t know the answer to them before you start deploying your questionnaire, then you’re proceeding without any solid underpinnings. A large number of amateur questionnaire-designers simply don’t want to know; they proceed in the hope that these issues don’t really matter, and that the truth will shine through despite the flaws in their methodology.

“I don’t know the answer” or “I don’t care” are not strong positions to take…

A more positive note

One thing that my long-suffering students often don’t immediately realise is that I have no objection to properly used questionnaires, or to properly used Likert scales and Likert-style scales. Used properly, they’re extremely useful.

As an example of how you can get fascinating new insights with very practical implications by using these approaches properly, here’s a short account of what one of my former students did.

Zoe was looking at how strongly university department home pages encouraged or discouraged potential students. The obvious approach was to use a scale running from “discourage” at one end to “encourage” at the other end.

Zoe didn’t do that. Instead, she used two scales. One scale ran from “not at all encouraging” at one end to “completely encouraging” at the other end. The other ran from “not at all discouraging” at one end to “completely discouraging” at the other end.

You might thing that the answer on one scale would logically have to be the opposite of the answer on the other scale, give or take some human error. Most of the time, that’s what happened.

Quite often, though, something different happened.

One fairly common response was that a home page was given a low score both for encouragement and for discouragement. When you stop and think about it (or when you ask the research participants about it afterward) there’s an obvious answer: the home page was just boring, with nothing very bad about it, but nothing very good, either. Those pages needed to have something positive added.

Another response that was less common, but still very much present, was that a home page was given a high score on both encouragement and discouragement. Again, that makes sense with hindsight; these were departments that had some very good points, but also had some very bad points. Those pages needed to have something negative removed; they were the opposite of the boring pages that needed to have something positive added.

This has far-reaching implications for any survey of attitudes, preferences and opinions, but very few such surveys use this approach, even though it’s cheap and simple to implement.

Concluding thoughts

When used correctly, these approaches can be powerful, clean and useful.

If you want to be on the side of light and virtue, then you need to read the relevant literature before using these approaches; general knowledge and common sense are nowhere near enough.

As is often the case, Wikipedia is a good place to start, but a bad place to stop. The Wikipedia articles on Likert scales and visual analogue scales provide a reasonable start, but they don’t have as much coverage as I would like of issues such as the limitations of human working memory (e.g. The magical number seven, plus or minus two, and subsequent work).

It’s also highly advisable to think long and hard about what use you will make of the data you get. If you don’t know what you’ll do with the data, then you’ll have a real problem when you have boxfuls of it (or, as is more often the case with questionnaires, when you have a response rate of 9%, and you’re trying desperately to dredge something believable out of the thirteen responses that have come back in the post/via email).

On which encouraging note, I’ll end.

Notes, links and sources:

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources for images:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domesday_Book#mediaviewer/File:Domesday_Book_-_Warwickshire.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Likert_scale#mediaviewer/File:Example_Likert_Scale.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harley-Davidson#mediaviewer/File:ZweiRadMuseumNSU_EasyRider.JPG

October 2, 2014

Timelines, task analysis and activity sequences

By Gordon Rugg

This article is a re-blog of part of a previous article about assessing whether or not you’ve met a client’s goals in a product design.

I’ve re-blogged it to form a free-standing article, for anyone interested in systematic approaches to recording and analysing people’s activities. I’ve lightly edited it for clarity.

The examples I’ve used below relate to product evaluation, but the same principles can be applied to other human activities, such as how people make decisions when shopping, or how people find their way around in an unfamiliar place.

Activities, tasks, and usability

There are various ways of measuring how easy it is to use a product. Some common measures are:

Time taken to perform a given task

Number of separate actions required to perform a task

Number of times a user makes a mistake when performing a given task

Number of times a user hesitates or goes to the help pages

Number of times a user mutters or swears

Number of times a user smiles or says something positive

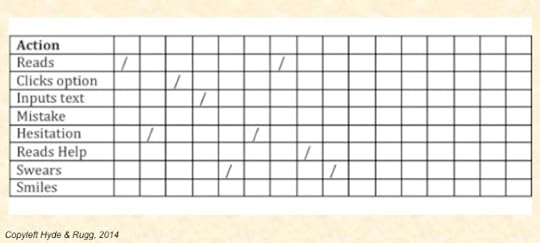

It can be useful to have a tally sheet for recording how often each of these things happen. Other useful aids include a timeline sheet and Therblig-style notations.

Tally sheets

A tally sheet is for recording how often each thing happens. It can take various forms – we advise using whatever works best for you.

Here’s an example.

Timelines

A timeline sheet is different from a tally sheet in that it records the sequence in which actions occur. There are various ways of doing this; for instance, each column might just represent the next activity, regardless of how long each activity lasts, or each column might instead represent a specified length of time, such as five seconds. Timeline sheets can be useful for spotting patterns and sequences of activities.

Here’s an example.

This timeline tells a story that would be missed by a tally sheet.

The user has begun by reading the screen (first column), but they’ve then hesitated (second column), which tells you that maybe the on-screen text isn’t easy enough to understand.

Next, they click on an option and they input text, followed by swearing, which suggests that the software didn’t do what they were expecting. They hesitate, read what’s on the screen, and then go to the Help option. This tells you that the text on screen didn’t give them the information they needed; you’ll need to fix that. After reading the Help option, they swear again. This is telling you a clear, vivid story about what’s going wrong, and what needs to be fixed in the next version.

Hint: When you’re trying to keep track of how long someone is spending on each activity, it’s usually not practical to use a watch or a mobile phone to measure the time, because you’re having to look at too many things at once. It’s usually much easier to count the seconds in your head as “One second, two seconds, three seconds” etc.

Another hint: Swearing is your friend. It tells you where significant problems are occurring, that you need to fix. A surprising number of people don’t transcribe swearwords when they’re recording sessions like the one above, on the grounds that “swearwords are rude”. This is a major mistake, because swearwords are one of the best indicators of where problems are occurring.

Timelines overlap with Therbligs, which are a well-established notation for activities.

Therbligs

Therbligs were originally devised as a pictographic notation for recording sequences of physical actions in manual tasks, such as assembly-line work in factories. There’s a core set of commonly used notations for activities such as “pick up” and “visually inspect” which are shown below.

There’s an explicit expectation in this approach that you’ll need to add some new notations to fit whatever topic you’re working on, such as a notation for “press Return key” or “press back arrow” if you’re using this approach to record what people do when using some new software.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Therblig_%28English%29.svg

Therbligs have been around for a long time, and they’re still useful today.

In a later article, I’ll go into more depth about Likert-style scales and questionnaires.

Notes and links

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the underlying theory in my latest book, Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

There’s more about data collection methods in my book with Marian Petre, A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

Rugg & Petre, A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

There’s a reasonable Wikipedia article about Therbligs here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therblig

September 27, 2014

Life at Uni: Why is my timetable a mess?

By Gordon Rugg

Every year, huge numbers of new students start university, and are surprised to discover that their timetable is very much a work in progress (and sometimes, a work of fiction). Every year, understandably, huge numbers of new students react to this discovery by wondering why universities crammed with alleged geniuses can’t sort out something as simple as a timetable. It’s not an encouraging start. This article is about the reasons for this state of affairs.

The main reason is that timetabling actually isn’t simple. In reality, it’s hideously complex. The timetable for a single university has to handle thousands of students, hundreds of modules, hundreds of academic staff, and hundreds of rooms. Very few of those students want lectures first thing in the morning or last thing in the afternoon, or on a Monday or Friday, so some slots are much more in demand than others.

Reconciling all of these issues is a huge, messy problem, but it could in principle be resolved by using smart software; some universities already use cutting-edge software that can perform impressively well, if other things are equal.

Unfortunately, the big spanner in the works is that other things usually aren’t equal. Here’s a classic example of why timetables are often fluid until well after the first week.

Suppose that you’re in a practical computing class of twenty students, and that you’re timetabled in a room that has twenty computers. That’s nice and straightforward.

Now suppose that one more student decides to sign up for the module. This means that you can no longer fit everyone into the room; even apart from the issue of not having enough machines, there’s the more significant issue that Health and Safety regulations take a hard line on room capacity, and quite right too.

So what happens? What happens is that either the session needs to be moved to a bigger room, or if that isn’t feasible, we now need to schedule two separate sessions in the same room. Either way, we’re looking at a timetable change. That change will probably have all sorts of ripple effects, and it’s a change that nobody could have predicted in advance.

If it was just a case of one or two students changing their modules, we could probably work round it by always booking rooms with some spare capacity. In practice, the numbers on some modules can be wildly unpredictable, for all sorts of reasons.

So, in conclusion, timetables are usually works in progress, and usually the reasons are because of the way the world is put together, rather than a reflection on the competence of the university.

That’s maybe not the most encouraging message ever, so here’s a nice picture of some contented kittens as a soothing final note. The next article in this series will be about something positive and encouraging.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitten#mediaviewer/File:Laitche-P013.jpg

Notes

There’s more about university life in my books with Marian Petre:

The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Unwritten-Rules-Research-Study-Skills/dp/0335237029/ref=dp_ob_image_bk

Rugg & Petre, A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

Related articles:

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/23/life-at-uni-lectures-versus-lessons/

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/07/whats-it-like-at-uni-the-people/

There are a lot of other articles on this site about academic life and education, including topics that students often have trouble with, such as the differences between academic writing and other types of writing. They’re tagged under “education” and/or “craft skills”. We hope you’ll find them useful; if you’d like to see more on some particular topic, let us know via the comments section, and we’ll see what we can do.

September 26, 2014

Why Hollywood gets it wrong: Conflicting conventions

By Gordon Rugg

Movies wilfully ignore and distort facts and truth for a wide range of reasons, most of them all too familiar. The usual suspects include:

Cost

Ignorance/not caring

Going for even bigger special effects than the last movie

Soul-less studio executives over-riding the director and/or scriptwriter

Going for the perceived lowest common denominator/broadest audience

In this article, I’ll resist the temptation to rant at length about those reasons, and will instead look at a less obvious problem which has some interesting underlying theory. It takes us on a journey across thousands of years of art, via some detours into geometry. It’s a variant on the problem of social perspective clashing with linear perspective (which might possibly be why it hasn’t received much attention in the past). Anyway, here’s an image that incorporates some key examples, after which I’ll unpack the concepts involved, and briefly outline some of their implications for cinema and for the wider world.

This article was inspired by a well-informed YouTube post by scholagladiatoria on the shortcomings of a classic swordfight scene in the 1977 movie The Duellists.

The post was mainly about the positions adopted by the two duellists, where the swords were held high, rather than with the hilts around waist height. (I’m using the still image below under “fair use” policy, as a low-resolution single image being discussed for academic purposes.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2KWTEhyVX8

As is often the case with obscure technical details, there are arguments for and against the original post; the comments section on the article contains detailed and courteous discussions of whether or not that particular high demi-quarte engaging guard was common in the Napoleonic period.

As is also often the case, one of the points in the original post sparked a memory of something from a very different field that gives a new possible perspective. That “something” is the problem that artists faced when trying to handle two conflicting conventions in paintings. Although this problem sounds about as esoteric as a problem can be, it’s just one manifestation of a problem that occurs in a wide range of fields. I’ll discuss the art case first, and then look at the broader implications.

Size, images and art

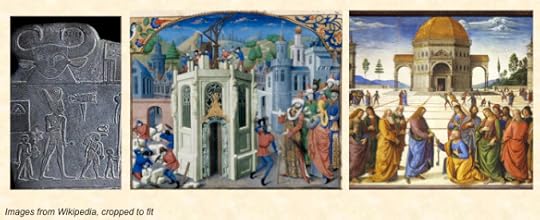

The problem looks simple. If there are two or more people in an image, and the people are shown as different sizes, what do the different sizes mean? Here’s an example (original image cropped to show detail).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narmer_Palette#mediaviewer/File:Narmer_Palette.jpg

It’s a detail from one of the earliest major works of Ancient Egyptian art, the Narmer Palette. The tall figure to the left of the picture is a pharaoh, wearing the distinctive double crown. The other figures come in at least two sizes. What do the sizes mean? There are several possibilities, including the following:

The figures accurately show people who are at least three sizes – perhaps the pharaoh as an adult, some teenagers, and some young children

The figures show people at three different distances – near, medium and distant

The figures are showing something else

In this case, the answer is “something else”. The artist is using social perspective, where the size of a figure is used to show how important the figure is. The pharaoh is of greater importance than any other person in Ancient Egypt, so he’s shown as tallest. People of moderate importance are shown as moderate in height, and people of negligible importance are shown as small.

This convention made a lot of sense in a status-conscious ancient world that wasn’t too bothered about literal accuracy in images. Throughout most of history, the artist’s job was to depict whoever was paying them in as flattering a way as possible. There were some exceptions, such as Amarna style in the reign of Akhnaten, and classical Roman portrait busts, but on the whole, any artist who knew what was good for them would keep well clear of being too accurate in their portrayals of powerful patrons.

This was still the case in the late Middle Ages. Here’s an example. On the left side of the picture, the figures of the masons are shown fairly accurately in terms of proportions relative to the building. On the right side of the picture, the artist has reverted to social perspective. The results are amusing to modern eyes.

The reason that it’s amusing is our old friend, ambiguous parsing of a non-threatening image.

This image is using one convention for what size means (i.e. social status of the person depicted) on one side of the picture, and a different convention for what size means (i.e. relative physical sizes of people and objects being depicted) in the other. The two conventions are incompatible, unless the artist does some very careful juggling of the composition, such as having the most important people in the foreground and the less important people in the background, at distances proportional to their importance.

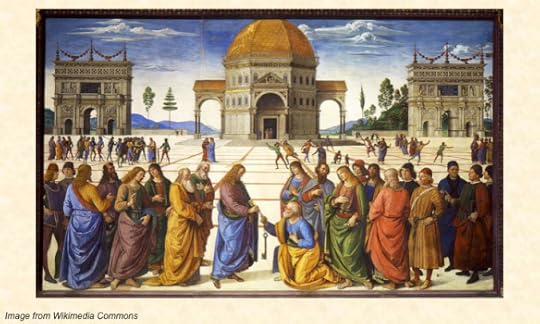

The next image shows what happened after a Renaissance genius called Filippo Brunelleschi tidied up the underlying theory of what’s now known as linear perspective. It’s a set of geometric principles that tell you how big a given object will appear at a given distance, if you’re portraying it realistically. These principles were enthusiastically adopted by the major artists of the time, as in the image by Perugino below.

If ever a picture sent a message of an artist having fun with a brand new toy, in the form of a new set of rules for handling perspective, then this picture is it.

Linear perspective is now the dominant convention in Western art, and has been since the principles were formalised back in the Renaissance.

So, that’s a brief overview of perspective and relative proportions in art. What does this have to do with movie realism?

Back to movie conventions

The thing that struck me when viewing the YouTube post about The Duellists was that the film’s director would quite possibly have been faced by a very similar problem to the ancient artists, in terms of trying to juggle two mutually contradictory sets of conventions.

One set involves historical and physical realism. Ridley Scott paid a lot of attention to this in the movie, and was much praised for it.

The other set involves cinematic conventions for depicting emotion. For instance, a low angle shot of the protagonist outlined against the sky is a cinematic convention for showing that character as heroic; conversely, a high angle shot from above and at a distance shows the same character as relatively insignificant. Directors also use close-ups of the protagonist’s face, or sometimes hands, so the audience can see the emotions (e.g. a twitch of the eye, or a nervous tremble of the hand); long shots hide that information.

So what happens when you want to show the audience the emotion that a major character is feeling in a duel? You’ll probably want to show close-ups of their face, and quite possibly of their hands as well, if you can. So far, so good.

What happens, though, if historical accuracy means that the main swordplay in the duel occurs at a level that distracts the audience’s attention away from the character’s face? A lot of the attacks in real sword fights were aimed at the legs; a lot of stances involved holding the hilt of the sword around waist height, so the tip of the sword would be in front of the fighter’s face in a way that might be distracting to the audience.

In these situations, there’s a strong temptation to have the character use comparatively rare moves that work better for the camera. It’s not telling a lie, but nor is it the complete truth.

In the case of The Duellists, having the actors use this high guard position means that all the physical and emotional action is happening in a single line of sight, rather than being distributed across the screen. It’s a neat solution, though at the price of pushing the boundaries of historical realism.

The bigger picture

Conflicting conventions in art and film are usually little more than an annoyance to some of the audience.

In other areas, though, such as design, they can have much more serious consequences.

At least two aircraft crashes were caused by designers having to choose between two conventions for instrument layouts which were both perfectly sensible, but which were mutually incompatible. When pilots trained on one layout switched to an aircraft that used the other layout, it was only a question of time before something went wrong.

At a less traumatic level, this issue crops up every time you have to write the date on a form. There are at least half a dozen possible conventions for the order and format of the date, month and year, and most of them seem to be in active use somewhere or other. Again, they’re logical and sensible (well, most of them at least) but they’re mutually contradictory.

There often isn’t a brilliant solution to this problem of mutually conflicting conventions, but being aware of the problem improves the chances of finding a solution if there is one. This is another theme to which we’ll return in later articles.

Notes, links and sources:

The Duellists is a beautifully made film, with an intelligent script and excellent performances, as well as considerable attention to detail. It’s well worth watching.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0075968/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Duellists

The film is based on a short story by Joseph Conrad, based on the true story of two French Napoleonic officers who fought thirty duels against each other over the course of almost two decades.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Fournier-Sarlov%C3%A8ze

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Dupont_de_l%27%C3tang

Related previous articles:

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/02/18/parsing-landscapes-and-art-some-speculations/

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/02/11/parsing-designs-and-making-designs-interesting/

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/05/the-uncanny-valley-proust-segways-and-the-living-dead/

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/02/01/making-designs-interesting/

Sources for images:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narmer_Palette#mediaviewer/File:Narmer_Palette.jpg

September 23, 2014

Life at Uni: Lectures versus lessons

By Gordon Rugg

A lot of things at university look very similar to things in school, but are actually very different. Lectures look like lessons to a lot of new students at university, but they’re very different beneath the surface.

One major difference is this:

In a lesson, the teacher is someone who knows the textbooks.

In a lecture, the lecturer is often the person who wrote the textbooks.

It’s a rule of thumb – some teachers write textbooks, and many lecturers don’t write textbooks, for various reasons – but it brings out a key underlying point. Lecturers do a lot of things in addition to delivering lectures, and a lot of lecturers are world class experts in their fields.

Student reactions to this vary.

Some students view this as an opportunity.

Some students view this as intimidating.

Most students either don’t know this, or haven’t thought about the implications.

Image from Twitter

I’ll return to this theme in later articles; it’s an important positive point about being at university. Teaching is the central focus of what a school teacher does; lecturing is only one part of what a university lecturer does, and in many cases it’s a minor part of the lecturer’s role compared to research or other activities.

Another “part of the bigger picture” difference is that lessons tend to be more self-contained coverage of a topic, whereas lectures are often just one part of the coverage of a topic at university; the lecture is often complemented by tutorials and/or seminars and/or lab and/or practical sessions where you discuss and/or practise the topics that were described in the lectures. I’ll be writing about tutorials etc in later articles.

Some points you might find useful in lectures:

Lecturers vary enormously in their approaches to lecturing, making generalisations difficult. Having said that, the suggestions below are usually useful.

Turn up on time if you can, because the first five minutes are usually where the lecturer gives an overview of the key points in the lecture, making it easier for you to get your head round the topics.

Don’t assume that more handouts means better student support; as you progress through university, you’ll move from a fair amount of support towards more independence, and more being expected to think and learn for yourself.

Don’t ask whether something that the lecturer has just mentioned will be in the exam; this usually comes across as shorthand for “I’m lazy, and want to do the minimum possible”. This isn’t a good signal, especially if you might some day want to ask that lecturer to write you a job reference.

Listen actively; try to work out what the key points are that the lecturer is making.

Remember that you get marks for showing your knowledge of content from the module that the average person on the street doesn’t know. For some topics, you’ll already have a “person on the street” or a “well-informed amateur” knowledge. The best mark you can expect from that knowledge on its own is a low pass; you get marks from knowing the more advanced stuff. So, if the lecture’s about something like how to make software user-friendly, don’t skip it on the grounds that you already have lots of opinions about this topic; opinions don’t get you marks.

Take active notes; this helps you understand and remember. “Taking active notes” doesn’t mean “writing every word the lecturer says”. It means something more like “note the key points and concepts that the lecturer mentions” and like “note the ways that you can easily show sophisticated knowledge about this when it’s assessment time”. I’ll be writing more about that in later articles.

If you’re lost and puzzled, try looking lost and puzzled. Most lecturers are experienced in reading the audience; if we see that the students are suddenly looking baffled, then we’ll usually re-wind and try a different way of explaining the topic that caused the problem.

If you’re still lost and puzzled, try asking the lecturer about it at a suitable time. Immediately after the lecture isn’t usually the best time for long explanations, but you could catch the lecturer then, and ask if you could book a short meeting to go over the topic in more detail.

Don’t be a snotty little brat. A lot of lecturers will do things to brighten up lectures and/or to illustrate a point more vividly and/or to give you “off the record” information that is likely to be invaluable to you in later life. If one student decides to complain to The System because they think that this isn’t proper lecturing, then the lecturer is likely to revert to the “death by PowerPoint” delivery style for the rest of the module delivery. (Yes, we do get students who think that they should have the deciding opinion on what constitutes “proper” lectures.)

Don’t be a dick. Most lecturers clamp down hard on people speaking while someone else is speaking (whether the lecturer, or a student asking a question) for the simple reason that this makes it difficult for other students to hear. If you find a lecture boring, and you choose to give up on it, then do something silent like watching cat videos on the Internet, rather than distracting students who do want to learn.

Treat the lecture as a shared experience. If you and others are finding a topic difficult, then a polite, constructive meeting with the lecturer can often work wonders. Most lecturers want lectures and courses to go well, too. Cynical lecturers want this to keep The System off their back; nice lecturers want it because they’re nice.

Other thoughts

Your university will almost certainly have large amounts of learning support available if you want to learn more about learning. Surprisingly few students take advantage of the resources which are available, and which can greatly reduce hassle and stress if you’re finding it difficult to cope with a course or a particular topic.

In later articles in this series, I’ll be looking in more depth at the opportunities that universities offer. A lot of students are unaware of those opportunities, or mistakenly believe that the opportunities involve a lot of extra work, and/or are only available to a handful of supergenius students. In reality, if you understand how those opportunities work, you have a good chance of achieving things that you never dreamed of, while having a lot more fun along the way.

On which positive note, I’ll end this article.

Notes

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about university life in my books with Marian Petre:

The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Unwritten-Rules-Research-Study-Skills/dp/0335237029/ref=dp_ob_image_bk

A Gentle Guide to Research Methods:

http://www.amazon.com/A-Gentle-Guide-Research-Methods/dp/0335219276

Related articles:

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/09/07/whats-it-like-at-uni-the-people/

There are a lot of other articles on this site about academic life and education, including topics that students often have trouble with, such as the differences between academic writing and other types of writing. They’re tagged under “education” and/or “craft skills”. We hope you’ll find them useful; if you’d like to see more on some particular topic, let us know via the comments section, and we’ll see what we can do.

September 19, 2014

150 posts and counting

By Gordon Rugg

This article is an overview of our blog articles so far, and of what is coming next.

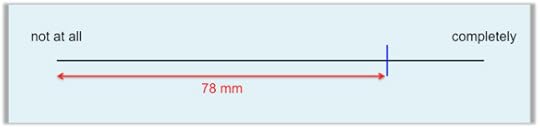

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

Image copyleft Hyde & Rugg, 2014

The knowledge cycle diagram above shows how the main themes of our work fit together.

We’ve now blogged about all of these themes, and about how they fit together. For some themes, such as elicitation, we’ve covered the main points fairly thoroughly. For others, we’ve only sketched out the key points so far; we’ll be covering those themes in more detail in later articles.

This article gives an overview of what we’ve covered so far, with links to some key articles. The links aren’t an exhaustive list, but they give a reasonable sample of the type of work we’ve been doing.

There are four main themes in the knowledge cycle, as follows.

One theme is elicitation: getting knowledge out of people. We’re particularly interested in knowledge that people find difficult to put into words, where questionnaires and interviews simply can’t tackle the problem. A lot of our work involves eliciting and clarifying requirements for products and services; we’re also interested in the mirror image of this, namely design of products and services that meet user’s requirements.

Some articles about elicitation and requirements:

Finding out what people want, in a nutshell

A unified model of requirements gathering

Why clients change their minds, and what to do about it

How to tell if you’ve met a client’s goals

Are client requirements infinite and unknowable?

A set of articles about client requirements, in eight parts: Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

A tutorial article on card sorts

A tutorial article on think-aloud technique

A tutorial article on self-report and related techniques

A tutorial article on structured observation of the environment

Some articles about design:

Making designs interesting

Parsing designs

Skeuomorphs – when a product is designed to look like something else

Designing for efficient use of space

An introduction to user-centred design

A worked example of design rationale

Our future articles on this theme will mainly be more detailed examinations of topics that we’ve already touched on.

A second major theme is representing knowledge – how best to visualise and categorise it. The Search Visualizer software is an example of how this can provide new ways of handling long-running problems. We’ve also looked at categorisation and classification, applied to a range of areas that include gender categorisation and use of space.

Some articles about representing knowledge:

Schema theory

Graph theory

Binary categorisation

Facet theory

Visualising categorisations of gender

Game theory

Systems theory

We still have quite a lot to write about this theme, both at the level of broad organising principles and of detailed nuts-and-bolts articles.

The third main theme is testing knowledge. There are large and well-established literatures on human error, logic, etc, that we’ve treated as foundational for our work – we haven’t tried to re-invent the wheel.

Our work in this area has concentrated on case studies where we’ve applied the Verifier framework to long-standing problems, such as the Voynich Manuscript and the literature on autism. In both those cases, we’ve published articles in the top relevant journals, as a way of checking that our findings provide solid new insights.

Some articles about modelling and testing knowledge, and about human error:

Practical issues for anyone trying to hoax something like the Voynich Manuscript, in eight parts: Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

A series with Gavin Taylor about the D’Agapeyeff Cipher, in five parts: Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Game theory

Systems theory

The mathematics of desire

Worldviews, and what people really want

Cherry-picking and use of evidence

Education and concepts of “natural”

Our future articles in this area will mainly be about unifying principles, about what people desire, and about how those desires skew our perceptions and judgments.

The fourth major theme is getting knowledge in to the human brain, thereby completing the knowledge cycle. Our work here has so far focused on filling gaps in the existing education literature, principally in two areas. The first of these is types of memory, knowledge, skill, etc, with particular reference to semi-tacit and tacit knowledge, and to the implications of these for delivery and learning methods. The second is the crucial distinction between serial processing and parallel processing/pattern matching, which has enormous implications for teaching and learning, but which appears to have received little attention in the education literature.

Some articles about education:

Life at university, part 1

Passive ignorance, active ignorance, and why students don’t learn

Connectionism, neural networks and mental processing

Models of knowledge with relation to teaching

Evidence-based approaches and education

“Natural” and “artificial” learning

Are writing skills transferable?

How complex should models of education be?

The limits to literacy

An education framework based on knowledge modelling

We’ll be blogging about this in the future both at the level of detailed articles on specific topics and at the level of big-picture overviews.

Future articles

Some articles due to appear over the next few weeks:

A series of articles on the realities of life at university, for students

A guest article by Gavin Taylor about visualising teaching plans

Non-verbal wayfinding and signage

More about design

More about how people’s views of the world are structured

In addition, as usual, we’ll be blogging about a wide range of interesting concepts that we’ve encountered in the byways of research.

Notes

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the underlying theory in my latest book, Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

September 12, 2014

Things people think

By Gordon Rugg

There’s a wryly humorous summary of models of humanity that floats around in academia. It appears in various forms; the one below has an astute punch line that highlights the amount of implicit assumption in the early models.

Models of humankind:

Man the fallen creation (the Bible)

Man the thinker (the Enlightenment)

Heroic man (Nietzsche)

Economic man (Marx)

Man the rat (Skinner)

Man the woman (feminism)

It’s humorous, but it cuts to the heart of the matter. The models that shape our lives – political models, religious models, economic models – are based on underlying assumptions about how people think and what people want. As is often the case with models, these assumptions are often demonstrably wrong.

In this article, I’ll examine some common assumptions, and I’ll discuss some other ways of thinking about what people are really like.

Images from Wikipedia and Wikimedia; details at the end of this article

Reason, unreason and emotion: The traditional view

As usual, the Ancient Greeks got into the story early, and as usual, they came up with a very plausible argument that dragged everyone off in the wrong direction for the next couple of millennia.

At the heart of that argument is a distinction between logic (viewed as cool, correct, ordered, but impersonal) and emotion (viewed as hot, often wrong, messy, but natural). The classical terms were Apollonian and Dionysian respectively; the Enlightenment version was Classical versus Romantic; the modern(ish) version is Spock versus Kirk.

It’s a plausible model, and it appears to correspond well with what people experience. The same, however, is true of expert practical jokes and confidence tricks; plausibility and correspondence with everyday experience aren’t guarantees of success.

An implicit assumption at the heart of this distinction is that “logic” is correct, and that therefore anything which is not “logical” will either be incorrect, or will only be correct by accident. (There’s a reason for the quotation marks, which I’ll unpack below.) This is a particularly important point because some of the most influential economic and political theories are based on a core assumption that consumers make rational choices.

So what happens when “logic” gives one answer, and “emotion/nature” gives a different answer?

In the Apollonian/Classicist/Spock view, “logic” trumps “emotion/nature”.

In the Dionysian/Romantic/Kirk view, “emotion/nature” trumps “logic.

There’s a third traditional way of viewing this question, which is to view it as a difficult balancing act. A lot of great drama is about the tension between these two choices.

The debate has been going on for over two thousand years. That’s usually a sign that there’s something wrong, or something missing. Those things started to become apparent once researchers started trying to produce rigorous, testable models of how to make decisions in the real world.

Algorithms, heuristics, serial processing and parallel processing

The first computers performed brilliantly at calculations within a traditional logical framework, dealing with clearly defined data. An obvious next step was to try using computers to tackle other types of problems where human experts were demonstrably fallible, such as medicine. The hope was that Spock-like rationality would produce better results. The reality was that computerised consistency often out-performed inconsistent humans. Logic, however, was another matter.

Formal classical logic is fine if you’re dealing with complete and correct information. Most real-world problems, however, don’t have that luxury; usually, real world problems involve messy, incomplete, unreliable information. It’s possible to handle many of these problems with a reasonable success rate, but the way that you have to handle them is very different from traditional classical logic. Instead of using algorithms – procedures which guarantee a correct solution if you follow them properly – you usually have to use heuristics, which are rules of thumb that give you a better-than-random-chance likelihood of a working solution.(There are also numerous different types of formal logic, designed for use with different types of input, which is why I’ve used quotation marks around previous mentions of “logic” which implied that only one type existed.)

Another issue about traditional classical logic is that it involves serial processing, i.e. a set of steps performed one after the other. However, most real-world activities require identifying objects and patterns, which serial processing can’t handle. For identifying objects and for pattern-matching, you need parallel processing, which is a very different beast. I’ve written about this distinction and its implications here, here and here.

The implication is that framing human thought, desires and behaviour in terms of logic versus emotion is the wrong starting point. To make better sense of these issues, you need a different starting point, and different framings. The following sections describe some more powerful framings. They’re speculations, but they’re speculations that are grounded in a broad range of theory and evidence, and that provide some interesting new insights and ways of thinking about human behaviour.

Sensory regulation, stimming and chilling, and unpredictability within a frame

One recurrent theme in human behaviour is sensory self-regulation. We use a range of activities to regulate our levels of sensory load, and to keep those levels within a preferred range. Some activities increase sensory stimulation; others reduce it. Sports and the entertainment media are typically about stimulation; many hobbies are about reducing sensory arousal. Some activities, such as music, occur in a range of forms, some of which provide sensory stimulation, and others of which are calming.

This framing makes sense of phenomena in a range of areas. In autism research, for instance, a commonly reported phenomenon is stimming, which involves sensory self-stimulation such as hand-flapping. Conversely, a common problem among children diagnosed with autism is sensory overload, leading to the child closing their eyes and putting their hands over their ears to reduce their sensory load down to manageable levels.

One key variable is whether something is perceived as threatening or not. I’ve blogged previously about how this relates to humour, horror, shock and other phenomena.

This issue makes sense of sports and games, and of genres within fiction (e.g. action movies and horror movies). All of these involve clearly established frameworks of rules and regularities, providing a safe surrounding context, within which there is uncertainty and novelty. In terms of sensory self-regulation, this provides a comfortable combination of safe predictability (the rules and conventions) and unpredictability (what the outcome of the game or movie will be, within those rules and conventions).

Power

This framing doesn’t at first sight appear to handle another important aspect of human behaviour, namely competition for status and power. There’s been a lot of research into this area, with some classic analyses by Weber and by Nietzsche, as well as a host of social anthropologists and sociologists. It’s clearly an important issue.

However, if we ask why competition occurs for status and power, then we get some interesting possible answers that take us back to the themes we’ve been examining earlier.

One set of answers relate to resources; the more status and power you have, the more resources you can control. The more resources you can control, the more ways you have of handling sensory regulation.

Another set of answers relate to control per se; the more status and power you have, the more you are able to control the people and the world around you. In both cases, you’re reducing possible threat, and you’re also increasing your ability to regulate your sensory input via increased access to sources of stimulation and sources of relaxation.

One obvious counter-argument is that many people don’t want power in the traditional sense of the word. I think that this point, however, doesn’t use a sufficiently nuanced interpretation of “power”. Power doesn’t need to involve giving orders to other people; as Weber pointed out, power and authority can take various forms. In the next section, I’ll look at power in the sense of perceived control of the surrounding world, including perceived control of interactions with other humans.

Script theory and Transactional Analysis

An important part of power is being able to reduce uncertainty. The more you know about what’s going to happen next, the less mental effort you need to put into contingency planning and into revising plans to handle new events.

This takes us back to pattern-matching; in this case, trying to identify regular patterns of behaviour in the human world and elsewhere.

Script theory and Transactional Analysis are two approaches that deal with regularities in human behaviour. At the heart of both approaches is the idea of the script, i.e. a regular series of actions, often with optional branches. The classic example is the script for eating in a restaurant, where the actions include being greeted by a waiter, being shown to a table, and hanging up coats. Scripts can include sub-scripts, and can also include provision for doing X if the script encounters event A, or doing Y if the script encounters event B. It’s a powerful model, that can model considerable complexity using a small number of basic concepts.

A lot of human behaviour involves scripts of this sort. They’re usually so familiar that we don’t notice them until we encounter a similar situation that requires a very different script, such as dining in a Chinese restaurant for the first time.

Scripts provide predictable regularities in our interactions with other people and with the world. One branch of popular psychology, namely Transactional Analysis, has attempted to describe a large number of scripts in plain English. This approach is particularly interesting because it provides explanations for why many people appear to want to end up in unpleasant situations. (Whether those explanations are correct is another question, but the underlying concept is interesting.)

An example is the Transactional Analysis script of “Mine’s bigger than yours” compared to the script of “General Motors”. These go in very different directions from the same starting point. Imagine a conversation that starts with the observation: “So you’re driving a Mondeo”.

The “Mine’s bigger than yours” script player will steer the conversation towards a claim that their car is better than the other person’s. The “General Motors” script player will steer the conversation towards a discussion of the pros and cons of different types of car. The first conversation is competitive and confrontational; the second is non-competitive and non-confrontational.

A central belief in Transactional Analysis is that every individual will actively attempt to manipulate interactions with other people in a direction that validates the individual’s beliefs about what the world is like. In the example above, someone who believes that the world is a competitive place will use the “Mine’s bigger than yours” script in conversations with other people. Someone who believes that the world is a co-operative place where people are happy to share knowledge will tend to use the “General Motors” script. Both of them will usually decide that the resulting conversation provides evidence that their world view is correct.

This principle can lead to counter-intuitive consequences, such as people attempting to validate their view that the world is a gloomy, lonely place by behaving in a way that makes their world gloomy and lonely. Paradoxically, that validation tells them that their model of the world is correct and that therefore they have as much control over their world as anyone can reasonably expect to have.

This issue has clear parallels with political and religious belief systems, which provide a framework that claims to give the individual a clear place in a predictable world. Any facts that challenge an individual’s framework are usually very unwelcome, because without that framework, the individual usually has only fragments of explanation to cling on to when trying to make sense of the world, rather than a coherent big picture.

This phenomemon might explain why believers in some frameworks occasionally flip from one set of extreme beliefs and behaviours straight to the apparent opposite. If your belief system contains detailed scripts telling you how “Our Group” behaves, and equally detailed scripts telling you how “The Hated Others” behaves, then if you abandon your original group, you have a ready-made detailed knowledge of an alternative framework that you can use.

Closing thoughts

This article is largely speculative. However, the speculations come from solid bodies of evidence and theory, and they provide interesting, often counter-intuitive, and often testable explanations for why people behave in some of the ways that they do.

In later articles, I’ll explore some of these issues in more detail.

Notes

You’re welcome to use Hyde & Rugg copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book: Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Sources of images (some cropped to fit):

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dionysos_panther_Louvre_K240.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Apollo#mediaviewer/File:Chryselephantine_Delphi_ver2.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_T._Kirk#mediaviewer/File:Star_Trek_William_Shatner.JPG

September 7, 2014

What’s it like at Uni? The people…

By Gordon Rugg

If you’re about to start your first year at university, and you’re feeling unsure and nervous, then you’ve got plenty of company. Most new students feel that way, though not all of them show it. This is the first in a short series of articles for people in your situation, about key information that should make your life easier.

This article is about roles at university. The American cartoon below summarises them pretty accurately.

So what are the roles other than “Elmo the undergrad” and how are they likely to affect you?

Grad students: In Britain, these are usually “PhD students” or “teaching assistants” or “demonstrators” in practical classes. They’re usually cynical and stressed because of their PhDs. They usually know the university system well, and they’re very, very useful people to have as friends. (Really bad idea: Complaining to the university that they’re not real, proper teachers.)