Patrick Kelly's Blog: PATRICK KELLY—AUTHOR BLOG, page 7

April 22, 2014

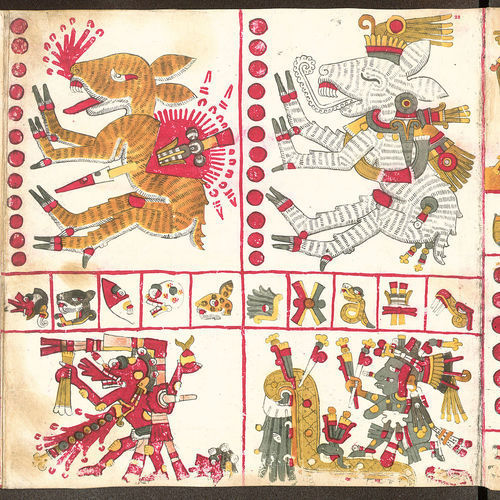

Demon of the Week 018

"Kasha" from the Gazu Hyakki Yagyō by Toriyama Sekien, ca. 1781.

This comes a day late. Sorry for the delay.

The kasha (火車, translates literally to "burning chariot" or 化車, "changed wheel") is a Japanese yōkai that "steals" corpses from cemeteries, especially targeting those who died as a result of an over-accumulation of evil deeds.

In many cases the kasha's true identity is actually a cat yōkai, and it is also said that cats that grow old may turn into kasha. There are tales of the kasha in many Japanese classics (the Kiizō Danshū, the Shin Chomonjū, and others).

As a method of protecting corpses against kasha, in Fujikawaguchiko—at a temple that a kasha is said to live near—a funeral is often performed twice, and it is said that by putting a rock inside the coffin for the first funeral, this protects the corpse from being stolen away by a kasha. Also, in Ehime prefecture, it is said that leaving a razor on top of the deceased's coffin can prevent the kasha from stealing the interred corpse.

April 18, 2014

Image of the Week 017

In this oil painting of the Tower of Babel—one of three such works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder—we see the building's construction. The structure was believed to be filled with magic and symbolic powers; its name meant "God's door." Its extraordinary height was meant to be a link between the divine, heavenly dimensions above and the human, earthly one below. At the top of the tower, astrologers and magicians looked for astral signs and channeled to earth the spiritual energies of the stars. Each floor of the tower corresponded to a planetary sphere or zodiacal sign.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563.

April 17, 2014

Myth of the Week 017

In Mesoamerican folk religion, a Nagual or Nahual (both pronounced na'wal) is a human being who has the ability to magically turn into an animal—typically a donkey, turkey, or dog, but sometimes more powerful animals such as a jaguar or puma.

Naguals may use their powers for good or evil, according to his or her personality. The general concept of nagualism is pan-Mesoamerican, and is linked with pre-Columbian shamanistic practices. The system is also tied to the Mesoamerican calendar system, for divination rituals. Also, the birth date of a person can determine whether he or she will be a Nagual. Mesoamerican belief in tonalism, wherein all humans have an animal counterpart to which their life force is linked (think spirit animal, à la Fight Club), is also part of the definition of nagualism. In English, the word is often translated as "transforming witch," though translations without the negative connotations of the word can be found, such as "transforming trickster" or "shape shifter."

The Threat (Animorphs #21) by K.A. Applegate

Also see Animorphs. Okay, so I'm mostly kidding, but the similarities are there.

April 16, 2014

Note of the Week 017

The following excerpt is from Taking Jezebel, Chapter VI.

Peter made for the pier, which stuck out into the Pacific like the continent’s own corroded protuberance. It seemed to bob in place alongside the ferris wheel, which stood on stilts and swayed in pace with its ligneous neighbor. Both seemed to hang by their last fragile threads, ready to collapse at any moment. Along the way he spotted two young women holding hands. One had a mohawk, dyed blue, and a piercing shaped like a bone struck horizontally—and stiffly—through her nostrils. The other was morbidly obese and wore too-tight clothes, her love handles rolling over the sides of her dirty black jeans.

When Peter passed them, they glowered toward him. The fat one raised her plump hand to expose her middle finger, and she grimaced like a feral cat, her fulvous teeth bared.

He hurried along. As he made his way farther out along the wharf, he ran his hands across the rope suspended at its edge. He let its coarseness grate against his palms and stopped to reflect on the scene, plopping into a seated position with his legs dangling over the edge of the construction, suspended ten feet above the billowing ocean below. Bits of salt water picked up in the sea breeze and sprayed against his calves. He stared up at the big, lifeless ring of the Circular Serpent above him. It floated in place, and its little cabs swayed indistinctly. What looked like a girl in one of the lower compartments peered down at him, met his gaze, and matched his insouciance. It was only a doll.

While he swung his sandaled feet above the eddies, a stranger passed along the pier behind him, quiet as a breath.

Peter rose to leave—to find a less macabre stretch of beach—and saw the newcomer. The man waltzed unhurriedly toward the far end of the pier with his back turned to Peter. He was wearing unremarkable gray track pants, which floated around his slim form, and a black hoodie pulled up over his head. The man approached the very tip of the walkway and turned sideways, revealing his profile: a fat lip, bulged and purple. His nose dribbled gouts of green fluid. The one eye that was visible looked swollen shut, its shape bloated, tumescent with bruising.

Peter walked toward the man and shouted, “Hey! You okay?”

The stranger’s lower jaw unclenched and shot downward, releasing a flow of spittle that stained the boards between his sneakered feet. His mouth clicked back and forth, unhinged and shut with force, while his tongue rolled loosely around the repository of his mouth. When he turned to face Peter, the man released a grating, clicking sound—something akin to the noise of an electric can opener. His malformed face, now fully exposed, showed a neck swollen outward to meet the slope of his chin; there was no difference in width between the bulged shape of his face and throat. His lips were fleshed out by the bloating of his tongue, which lolled freely about its moistened home due to a shortage of teeth (the ones that were present had browned and rotted, hollowed out with infection like the small cavities of a crow’s wet, staring gaze). The skin of his lips crackled with a milky, pus-hardened casing between rows of open sores. His left cheek was pocked with small holes, like burning shrapnel had shredded out fresh, hot openings in the side of his face, to reveal his shining gums and jagged, crushed molars. His left nostril was stamped closed by a thin overgrowth of some slick membrane. The right nostril hung open, receptive. There, tiny foramen interlaced together—writhing, stringy fibers deep inside of him, attached to the cartilage like parasitic worms. When the mangled orifice of his nose dilated with respiration, those white organic threads swelled, brimmed, and then shrank down again. His ears and brow were shrouded by his hoodie, smudged with effluent or worse, but those eyes—even in the shadow of his browned jersey—were crammed with blood and emotion, like the hate of a rabid wolf. The sockets were tumefied by an overgrowth of fatty tissue, and puffy blood vessels framed his barbarous gaze like a throbbing, biotic trellis.

April 15, 2014

Novel of the Week 017

The Book of the New Sun is a Dying Earth series by fantasy author Gene Wolfe. It is comprised of four novels—The Shadow of the Torturer, The Claw of the Conciliator, The Sword of the Lictor, and The Citadel of the Autarch. The tetralogy follow the rise of Severian from apprentice at the Guild of Torturers to his ultimate fate, a battle with the dreaded Autarch.

The novels have won numerous awards, and are considered by some to be the apotheosis of "science-fantasy" fiction.

April 14, 2014

Demon of the Week 017

In Akkadian and Sumerian mythology, Alû is a vengeful spirit of the Utukku that goes down to the underworld Kur. The demon has no mouth, lips or ears. It roams at night and terrifies people while they sleep. Spirit possession by Alû results in unconsciousness and coma. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Alû is the celestial Bull.

April 11, 2014

Image of the Week 016

In Titian's Allegory of Prudence, the artist's face represents the past and old age; that of the son, the present, and maturity; the grandson, the future, and youth.

Titian, Allegory of Prudence, 1566.

April 10, 2014

Myth of the Week 016

A will-o'-the-wisp or ignis fatuus (in Latin, "foolish fire") is an atmospheric ghost light seen by travelers at night, especially over bogs, swamps, or marshes. It resembles a flickering lamp or lantern and is said to recede if it is approached, drawing travelers away from safe trails or pathways. The phenomenon is known by a variety of names, including jack-o'-lantern, friar's lantern, hinkypunk, and hobby lantern.

Arnold Böcklin, Will-o'-the-Wisp, 1862-1882.

In modern science, it is generally accepted that most ignis fatuus are caused by the oxidation of phosphine (PH3), diphosphane (P2H4), and methane (CH4), or by the bioluminescence of fireflies, glowworms, et al.

April 9, 2014

Note of the Week 016

How great does this look? From the incredible Lukas Moodysson.

April 8, 2014

Novel of the Week 016

Originally posted to Goodreads.

The Secret History—a tough one to review.

At its onset—and truly, throughout—this is very much a novel about spoiled, snotty kids. Initially, the characters' pretentious attitudes kept me from enjoying much of Tartt's gorgeous prose, but—surprisingly, as if by some arcane enchantment—my distaste for the likes of Charles, Camilla, Henry, and Francis transformed into something altogether different. Suddenly, all these characters' stuffy, self-absorbed mannerisms, their self-serving actions, served as proof of their pitted, existential quest. Their drinking, coke-sniffing, and their plotting: all were precisely apposite to Tartt's premise.

Something magical started to happen: in all the haughty, decadent exposition, a flicker of meaning appeared here and there, one that might offer the story's narrator an out from the dark world he's entered. Alas, that wouldn't provide for much of a story, would it?

No, it wouldn't; so Tartt throws a bacchanal and some murder into the mix—along with some other sordid goings-on, incest to boot. In theory, it sounds stagy, deliberate, and heavy-handed, but in practice it never comes across as such; brilliantly, it all works. Every simple statement, every minor detail, is wholly swathed in degeneracy and intrigue, which creates an uncomfortable, edgy feeling while reading (which, don't misunderstand, is strangely enjoyable). As Richard walks drunkenly down the streets of Hampden, I half-expected a specter to appear. Questions bounded 'round my skull with urgency: Was Bunny truly gone? Were the others plotting against Richard? Was Julian in on it?

When the answers to these questions weren't forthcoming, I realized something else: it was perhaps more pleasing to idle in the beauty of Tartt's prose than to solve the great mysteries; perhaps even better to languish (as her characters do) in the simultaneously desperate and beautiful afterglow of the violent deeds occurring in this chaotic, yet deceptively dulcet, world.

So much beauty is buried in this odd, secret universe of Tartt's that it's tough to sum up the final, raw feeling I was left with. Throughout my reading, I found that there were moments of outright pastiche, of genre tropes, but all this was superseded by those flickers of magic, of mystery. This is one tale I won't soon forget.