Patrick Kelly's Blog: PATRICK KELLY—AUTHOR BLOG, page 9

March 24, 2014

Demon of the Week 014

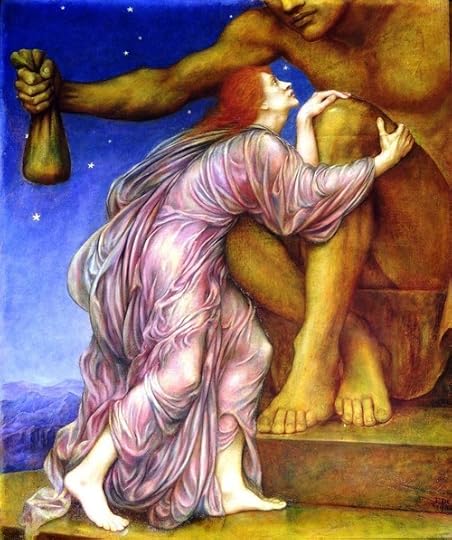

Mammon is commonly personified as material wealth, greed, gluttony, and injustice. He is often described as a deity, or as one of the seven princes of Hell.

Evelyn De Morgan, The Worship of Mammon, 1909.

Riches are called by the name of a devil, namely Mammon, for Mammon is the name of a devil, by which name riches are called according to the Syrian tongue.

— Peter Lombard, 12th century scholastic theologian

March 21, 2014

Image of the Week 013

In the painting, butterflies are a symbol of the volatility of thought, while the rainbow behind the interior canvas denotes the evanescence of ideas. Jupiter, the painter within the piece, alludes to the idea that every ordering principle needs a source of inspiration from the realm of ideas. Behind him, Mercury raises his finger, ordering silence; this is a metaphor for the quiet that precedes spiritual, natural, or artistic creation.

Dosso Dossi, Jupiter, Mercury and Virtue, ca. 1523-24.

March 20, 2014

Myth of the Week 013

Read about the Wendigo here.

The Wendigo was gaunt to the point of emaciation, its desiccated skin pulled tautly over its bones. With its bones pushing out against its skin, its complexion the ash gray of death, and its eyes pushed back deep into their sockets, the Wendigo looked like a gaunt skeleton recently disinterred from the grave. What lips it had were tattered and bloody [....] Unclean and suffering from suppurations of the flesh, the Wendigo gave off a strange and eerie odor of decay and decomposition, of death and corruption.

— Basil H. Johnston, Ojibwe teacher and scholar from Ontario, Canada

Also of note is the cult horror film Wendigo, based on the folklore. Directed by the great Larry Fessenden and starring the incredible Patricia Clarkson, the film was panned but remains an effective, atmospheric creep-fest, IMHO.

March 19, 2014

Note of the Week 013

Thanks to all 855 people who entered the Taking Jezebel giveaway! Wow, I could not have guessed so many folks would be interested in my humble tale. I so appreciate your desire to share in my odd world, full of freaks and dastardly creatures.

Heartfelt congratulations are due to Robert, Kat, and Alex, who've each won a signed paperback copy of the novel through Goodreads.

That's all for giveaways (for now), but don't hesitate to browse some reviews and give the book a try. I look forward to hearing your thoughts. Don't hesitate to reach out with any questions. I'm always happy to discuss your book, mine, or anyone else's.

March 18, 2014

Novel of the Week 013

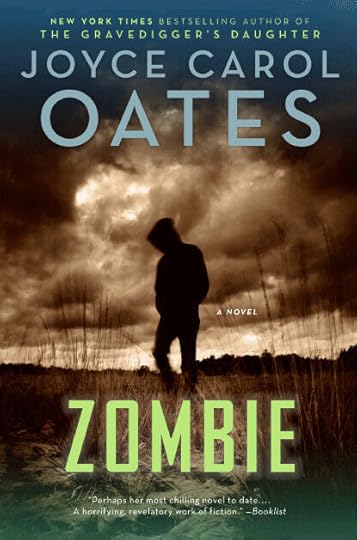

Zombie is not the JCO I remember.

Meet Quentin: a violent serial-rapist/killer and pedophile. Oates places the reader inside the mind of a social deviant, but succeeds only insofar as she shocks. These moments are daring enough to outweigh sudden, dramatic shifts in tone and style, which the narrative occasionally suffers from—switching from pedantic, broken English to deep, allegorical, highly poetic aphorism. The latter would feel more compelling (and authentic) if it didn't arrive at such odds with the rest of the slim volume's sparse, reflexive style of writing.

Altogether chilling, with a daringly auspicious ending...

March 17, 2014

Demon of the Week 013

Read about Marchosias here.

Marchosias as depicted in Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal, 1863.

March 14, 2014

Image of the Week 012

Whose midnight revels by a forest side

Or fountain some belated peasant sees,

Or dreams he sees, while over head the moon

Sits arbitress, and nearer to the earth

Wheels her pale course, they on their mirth and dance

Intent, with jocund music charm his ear;

At once with joy and fear his heart rebounds.

— John Milton, Paradise Lost

Henry Fuseli, The Shepherd's Dream, 1793.

March 13, 2014

Myth of the Week 012

Of the mythical Crocotta, a deadly dog-wolf hybrid, Pliny wrote:

...among the shepherds’s homesteads it simulates human speech, and picks up the name of one of them so as to call him to come out of doors and tear him to pieces, and also that it imitates a person being sick, to attract the dogs so that it may attack them; that this animal alone digs up corpses; that a female is seldom caught; that its eyes have a thousand variations of color; moreover that when its shadow falls on dogs they are struck dumb; and that it has certain magic arts by which it causes every animal at which it gazes three times to stand rooted to the spot. When crossed with this race of animals the Ethiopian lioness gives birth to the corocotta, that mimics the voices of men and cattle in a similar way. It has a unbroken ridge of bone in each jaw, forming a continuous tooth without any gum.

— Pliny, in his Natural History, c. AD 77-79

The Crocotta, as depicted in the 12th-century Aberdeen Bestiary, an illuminated manuscript bestiary.

March 12, 2014

Note of the Week 012

Here's a short excerpt from Taking Jezebel:

“All right,” the warden said disinterestedly, “let’s go. It’s a long walk from here.”

“No car?” Orson asked, half-joking but half-hoping there was one, rubbing his neck again, lips quivering.

“No car.”

Orson still pictured the faces of his sniggering, bumptious classmates, wondering if he should leave after all. And he couldn’t shake the embarrassment he’d faced, being held up by the warden like that.

The moon hung long and low above them as they darted over the crests of dunes, skipping over snake holes en route for what Orson hoped would be an experience as titillating as the Big Man had promised.

They made their way deeper, into the engulfing blackness of the desert, the ranger mumbling indistinctly to himself in a singsongy pulse, using words Orson couldn’t quite hear over the roar of the dry winds buffeting his eardrums, hardening his joints with their harsh chill. Their trek drew into an enduring blur of unabating, cruelly sloped drifts. They measured their slow progress by the point of the moon in the sky, though it wasn’t moving much.

Orson’s legs ached and his lips had long chapped over, but he pressed on, following closely in tow of the warden’s winking shadow, mirroring the pathway the giant carved and rejoicing at the occasions when his leader’s back provided him with a momentary shield against the wind, against the flecks of sand filling in the creases of his eyelids and the flaps of his ears.

Face my ownmost self, Orson thought. Yeah, right. If we ever get out of this mess.

The wind picked up, beating more violently against his naked cheeks, chaffing them into two rosy mounds as arid and swollen as the environs through which they traversed. This was the closest thing to a sandstorm he’d ever seen. The spineless extremities of those harsh currents whipped into Orson like a cat-o-nine-tails, cutting through his skin like butter. But just when he was ready to give up, to call it quits, to tell the warden to pick him up like a helpless infant and head back toward the banal, unremarkable world—just before saying, “Um, excuse me, but I think I made a mistake in coming here, might we please go back?”—the warden mumbled some words Orson finally did comprehend, and they were welcome words, soothing as watermelon juice is to a fiercely burning hangover.

The warden said, “We’re almost there. It’s just past the next crest. Look out for the shape of the monument.”

“Okay,” Orson said. He tried to check on the camera peeking oh-so-subtly from under the front flap of his backpack, to confirm that its little eye was still squinting imperceptibly from behind a carefully punched-in silver grommet—recording their every move—but the warden kept turning toward him, his big hands urging them forward.

Orson was almost certain he’d powered it up when he parked the beat-up rental. He could remember the feel of the little plastic ridges on the side of the power switch, the feeling of his thumb sliding against it as it made a soundless shift to the right, toward the position labeled ON.

But he wasn’t sure—just almost certain.

Ahead of Orson, the warden was mumbling again.

The moment was close—just around the corner, he said, so close at hand, one drift of sand away.

At last, it rose over the next dune like a golem’s stony hand—its fingers separated and protruding from the pebbly ground. The monument swelled before them; it was made up of giant and sturdy, forbidding pillars connected together by moss-covered cactus arms, like some deity’s barren canopy. It was an outcropping that evoked all the wonder of Stonehenge, but with an unequivocally violent undertone, as though whoever or whatever created the structure had been born with a seething madness which was so visible, so palpable in the form of the stones.

“There it is,” the Big Man said. “There’s the monument.”

“I see it,” Orson said, but almost wished he hadn’t.

March 11, 2014

Novel of the Week 012

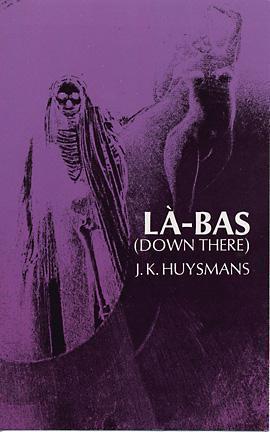

Là-Bas (English: Down There or The Damned) is a novel by the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans, first published in 1891. Là-Bas deals with the subject of Satanism in contemporary France, and the novel stirred controversy when it first appeared. It's the first of Huysmans's books to feature the famous character Durtal, inspired by the author himself, who would go on to be the protagonist of all of Huysmans's subsequent novels.

The plot of Là-Bas concerns the novelist Durtal, who is disgusted by the emptiness and vulgarity of the modern world. He seeks relief by turning to the study of the Middle Ages and begins to research the life of the notorious 15th-century child-murderer Gilles de Rais (who was also the inspiration for Bluebeard, the famous fairy tale character). Through his contacts in Paris, Durtal finds out that Satanism is alive and well in fin de siècle France. He embarks on an investigation of the occult underworld with the help of his lover, Madame Chantelouve. The novel culminates with the detailed description of a black mass.

As is usual for the work of Huysmans, decadent descriptions and deep pessimism punctuate much of Là-Bas, and the work shines as an enduring example of Huysmans's timeless erudition and wit, even amidst the novel's ominous goings-on.