M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 15

September 27, 2023

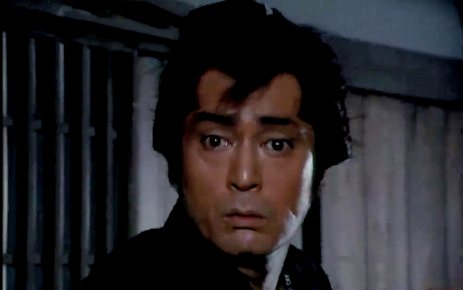

A Night to Remember / その夜は忘れない / Sono yoru wa wasurenai (1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #79

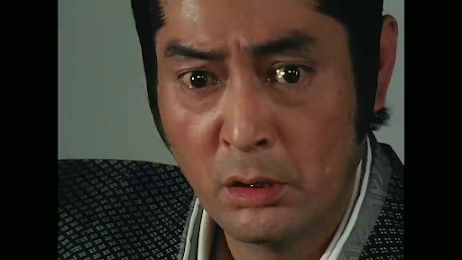

This Daiei production stars Jiro Tamiya as Kyosuke, a Tokyo journalist who is also something of a playboy. He’s sent on assignment to Hiroshima to cover the memorial ceremony for the 17th anniversary of the dropping of the bomb. He begins by visiting the museum, where he’s disturbed by the grisly artefacts on display and seems to hear the voices of the dead whispering to him. He also interviews some A-bomb survivors; one, a young woman with a disfigured face, is disconcertingly cheerful and has long accepted her condition, but Kyosuke nevertheless feels uncomfortable in her presence and has trouble looking her in the face. In fact, he’s so affected by what he sees and hears that, when a carefree young Japanese couple speed past him on a motorbike, he finds himself glaring at them resentfully.

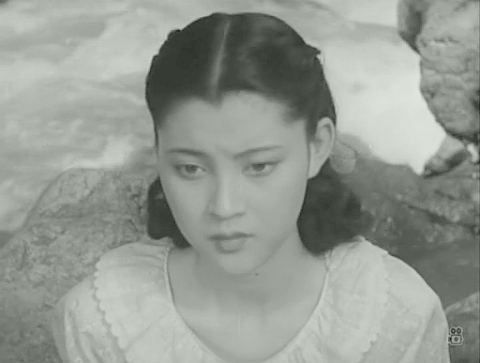

Hoping to take his mind off the bomb, Kyosuke meets up with an old friend, Kikuta (Keizo Kawasaki), who takes him to a bar, where he is introduced to the manageress, Akiko (Ayako Wakao). Kyosuke and Akiko are attracted to each other, but she seems uncommonly keen to avoid the topic of the bomb…

Kozaburo Yoshimura (1911-2000) was a highly respected director of serious dramas and literary adaptations (his 1951 version of The Tale of Genji is especially good). Here, he’s working from an original screenplay by Yoko Mizuki, Kosei Shirai and Tokuhei Wakao (no relation to Ayako as far as I’m aware). One of the film’s strengths is that it’s mostly shot on location, and veteran cinematographer Joji Ohara makes it look great. The fact that Yoshimura used several real-life A-bomb survivors in the cast also lends authenticity.

What really carries the film, however, is the performances of the two leads. In my view, among male Japanese film stars of the ‘60s, Jiro Tamiya was one of the best actors, and he puts across the conflicted feelings of Kyosuke very well here. Ayako Wakao has less screen time despite being top-billed, and first appears 24 minutes in; of course, when she finally arrives, she delivers her usual flawless performance.

The film has its flaws – Ikuma Dan’s music is often intrusive and unsubtle, while the story relies far too much on coincidence (Kyosuke has chance meetings with people that he knows on no less than three occasions!). However, the sensitive acting of Tamiya and Wakao makes this a genuinely moving experience.

September 25, 2023

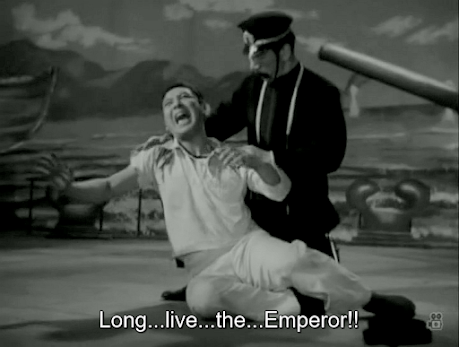

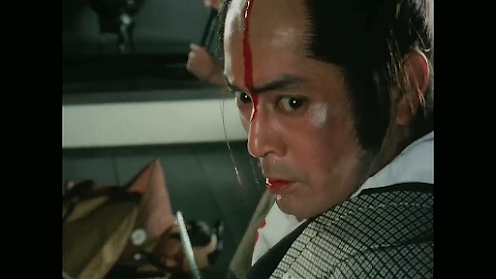

Get ‘em All / みな殺しの歌より 拳銃よさらば! / ‘Minagoroshi no uta' yori kenju-yo saraba! (From the ‘Song of Annihilation’-Farewell, Gun!) (1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #78

Hiroshi Mizuhara and Akemi Kita

Hiroshi Mizuhara and Akemi Kita

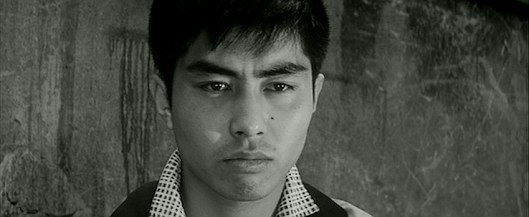

This Toho crime flickwas a vehicle for Hiroshi Mizuhara* (1935-78), a pop singer who had just becomehugely popular at the time. He plays Kyosuke, a young man fresh out of prison,who goes to stay with his brother, Kozo (Akihiko Hirata), and his wife, Mamiko(Yukiko Shimazaki). However, it’s not long before Kozo is killed in asuspicious hit-and-run – something which fails to make much impression onMamiko, who observes that she ‘can’t dance the mambo with a dead man’ andassumes she will simply switch brothers. Kyosuke, though, has other ideas, andbegins investigating his brother’s death.

First, he pays a visitto Kozo’s best friend, Tsubota (Tatsuya Nakadai), a crippled ex-boxer. Notwanting to shatter Kyosuke’s illusions, Tsubota decides not to tell him thatKozo was involved in a bank robbery with himself and five other men and thatthe loot has gone missing. Kyosuke leaves, still under the impression that Kozowas an honest citizen, but then he finds a coin locker key in his brother’swallet. When he opens the locker, he’s surprised to find a revolver inside;later, he gets in a fight with his ex-girlfriend’s new boyfriend, Namioka(Jerry Fujio). During the scuffle, his jacket falls open, revealing the gun,and Namioka immediately backs down. Realising his new-found power, Kyosukeorders Namioka to get down on all fours and ‘squeal like a pig.’ He's delighted when Namioka does just that, and the power of the pistol goes to Kyosuke’s head as he sets about gettingrevenge on the men who murdered his brother.

The director of thisfilm, Eizo Sugawa, had directed Tatsuya Nakadai in the excellent The Beast MustDie the previous year and had also written the script for A Dangerous Hero(1957) featuring Nakadai. I couldn’t help feeling it a pity that this third andfinal collaboration should be this, rather than a sequel to Beast – a film whichintroduced a fascinating Ripley-like antihero to Japanese cinema and leftthings wide open for a part two. Having said that, Get ‘em All is a well-made,entertaining and stylish noir.

In my opinion, Mizuharagives a good performance but doesn’t quite cut it as a film star. He appearedin around 20 movies (not always in the lead) but his career was harmed by hisalcoholism and gambling addiction. It’s a little strange to see him in thestarring role instead of Nakadai (who receives special billing), but Nakadaialways relished these slightly odd parts; in fact, it’s one of a number of ‘badleg’ roles he would play throughout his career. However, perhaps the role hadanother attraction for him as he had actually flirted with boxing beforebecoming an actor, but decided he didn’t like being punched in the face andgave it up. There’s a scene here in which he really goes at it with a punchingbag and it certainly looks like he had some moves; indeed, he later got into ascrap with Kinnosuke Nakamura in real life, and I think it was Tetsuro Tanbawho said that Nakadai was the best at fighting. Talking of Tanba, he’s alsogood here as the toughest of the gang members.

Also notable among thecast are Kurosawa favourite Seiji Miyaguchi in one of his trademark downtrodden-loserroles, and Kyoko Kishida (the Woman in the Dunes) as the girlfriend of anothergang member.

Get ‘em All was basedon the novel Minagoroshi no uta by Haruhiko Oyabu, who had also written TheBeast Must Die. In the original, the criminal gang are not bank robbers, butare involved in a black market morphine racket. While the loose adaptation hereis nothing special in terms of story, director Sugawa and his screenwriter,Shuji Terayama – later an art-house director known for films such as Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets– inject it with some nice touches of black humour, and emphasize the veryobvious Freudian symbolism of the pistol. Indeed, there’s an implication herethat Japanese men had been, in a sense, emasculated after the war by the occupying Americans;this is made most explicit when Kyosuke is nearly shot by a kid dressed as acowboy who has got hold of his gun and claims to be… ‘Burt Lancaster’!

* not 'Mizuwara'

September 9, 2023

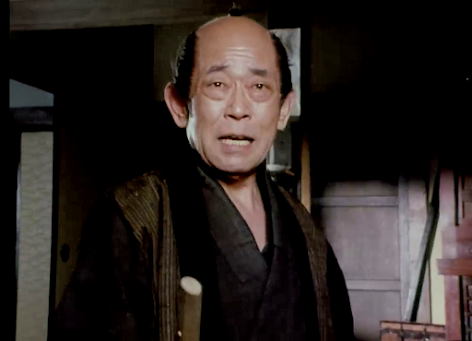

The Law of Hell / 地獄の掟 / Jigoku no okite (1982)

Obscure Japanese Film #76

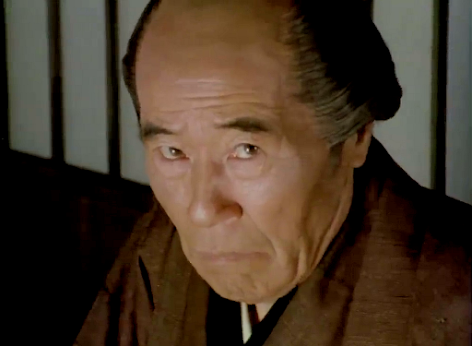

This TV remake of the 1971 film known in English as Inn of Evil, which also starred Tatsuya Nakadai, was very much a family affair for the actor. Based on a Shugoro Yamamoto story entitled ‘Fukagawa Anrakutei’, the scripts for both were written by Nakadai’s wife, Yasuko Miyazaki, under her pen name of Tomoe Ryu. The other important personal connection for Nakadai is that most of the cast were students from his acting school, Mumeijuku (a notable exception is Hideo Murota, who plays the mysterious drunk portrayed by Shintaro Katsu in the earlier film).

Nakadai was approaching 50 by the time of this remake, which is presumably why this time round he chose to play Ikuzo, the owner of the Anrakutei inn on a tiny island in Fukagawa (hence the title of Yamamoto’s story), rather than repeat his earlier part of Sadashichi the Indifferent, played effectively here by his student, the late Daisuke Ryu.

One issue I have with Yamamoto’s story is that it rather wants to have its cake and eat it in the way we are expected to accept that a gang of hardened criminals turn into a bunch of sentimental softies as a result of hearing one hard-luck story. However, if you can swallow that and make allowances for the fact that this is not a 2-hour Masaki Kobayashi movie, but a 90-minute TV drama, this is a pretty decent effort. Having watched a few of Nakadai’s early ‘80s made-for-TV movies now, I’ve been quite impressed by how well-lit, shot and staged they are in comparison to the often visually drab television drama served up during this period in the West. The director for many of these was Akira Inoue (1928-2022), who had been a feature film director in the 1960s, making pictures such as Zatoichi’s Revenge (1965), but who worked mostly in television from the 1970s on. Nakadai is of course excellent as the philosophical father figure here, giving a mostly restrained performance until things heat up in the climax, when he even gets to engage in a little swordplay.

Yasuko Miyazaki later adapted the story once more, this time for the theatre. It was first staged in 1997, a year after her death, with Nakadai again playing Izuko, and Nakadai has revived it several times since.

Thanks to Samurai Vs Ninja for making this available on YouTube here.

September 3, 2023

Evening Stream / 夜の流れ / Yoru no nagare (aka The Lovelorn Geisha, 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #75

Isuzu Yamada

Isuzu YamadaSonoda (TakashiShimura) is a wealthy businessman who owns a restaurant run by Aya (IsuzuYamada), whom he has repeatedly tried and failed to seduce. She’s actuallyhaving an affair with the cook, Igarashi (Tatsuya Mihashi), who has a foot injuryas a result of being forced to work barefoot when he was a prisoner-of-war inSiberia. Aya’s daughter, Miyako (Yoko Tsukasa), is also in love with Igarashibut unaware of her mother’s affair. The restaurant has several geisha whoentertain the guests. These include Kintaro (Yaeko Mizutani), who tends to getdrunk a lot and is eventually raped in a car while intoxicated; Beniko (EtsukoIchihara), who regularly attempts suicide for obscure reasons; and Masae(Mitsuko Kusabue), who has been left by her husband, Nozaki (Kazuo Kitamura), andis now in a relationship with a salesman (Akira Takarada), although Nizakikeeps turning up to sponge off her.

Takashi Shimura

Takashi ShimuraThis Toho production is unusual in being a collaboration between two directors – Mikio Naruse and Yuzo Kawashima – and it seems to have come about as a result of Kawashima’s admiration for his senior colleague. Reportedly, Naruse directed most of the interiors in the studio, while Kawashima handled the scenes shot on location, and it certainly looks that way. As might be expected from this approach, there is a certain unevenness of tone. Kawashima’s opening scene set at a swimming pool suggests we’re in for a moronic sex comedy, but the film becomes more serious and interesting as it progresses.

Tatsuya Mihashi

Tatsuya MihashiThe geisha portrayed here are not the high-class prostitutes of period dramas, but simply female companions and entertainers for hire, which is what geisha had become by the time this film was made (it’s set in what was then the present day). Nevertheless, it’s surprising to see geisha emulating westerners on their days off. They ride around in American sports cars, go to jazz bars and drink highballs, and it’s made clear that their shamisen skills are somewhat lacking compared to the geisha of the past. In fact, their materialism, pursuit of pleasure and lack of spirituality are almost akin to the ‘sun tribe’ youths seen in films such as Crazed Fruit (1956). However, although these women seem pretty vacuous at first, they do become more sympathetic as the various sub-plots unfold, and Kintaro’s rebellion is gratifying when it comes.

Kazuo Kitamura and Akira Takarada

Kazuo Kitamura and Akira TakaradaThe film was based on an original screenplay by frequent Naruse collaborator Toshiro Ide, and Zenzo Matsuyama, soon to become a director himself. It seems that Ide wrote the Naruse portions, while Matsuyama wrote Kawashima’s scenes. Each director also worked with a different cinematographer. I suspect that Naruse might have had an undeveloped, set-bound script by Ide on his hands and suggested that Kawashima add some exteriors showing what the women get up to on their days off (though this is pure speculation on my part). In any case, I felt that the Naruse scenes were stronger, though this might be partly due to the fact that he directed all the sections featuring Isuzu Yamada, who is exceptional. I don’t think I’ve ever seen another actor burst into real tears as suddenly as she does here. Yoko Tsukasa is equally convincing as her daughter, while Yaeko Mizutani proves herself the master of the drunk scene. The music score by Ichiro Saito features jazz guitar quite prominently and has not dated well, but on the whole this often maligned film rewards the patient viewer and is by no means the failure its reputation suggests.

Yoko Tsukasa

Yoko Tsukasa Isuzu Yamada

Isuzu Yamada Yaeko Mizutani

Yaeko MizutaniAugust 20, 2023

Dancing Girl / 舞姫 / Maihime (1951)

Obscure Japanese Film #74

Namiko (Mieko Takamine) is a ballet teacher married to university prof Yagi (So Yamamura). They have two grown children – Shinako (Mariko Okada), who aspires to be a ballet dancer like her mother, and her brother Takao (Akihiko Katayama). However, the marriage was an arranged one, and Namiko still has feelings for former sweetheart Takehara (Hiroshi Nihonyanagi), whom she still sees regularly, although their relationship is platonic. This puts an increasing strain on the marriage while Shinako and Takao look on uneasily. Meanwhile, Shinako’s disillusionment deepens when she finds herself powerless to help either Kayama – her former ballet teacher whose career has ended due to a war wound (Heihachiro Okawa) – or Tomoko (Reiko Otani), a fellow student reduced to working as a stripper in an effort to help her sick lover.

Mieko Takamine and Hiroshi Nihonyanagi

Mieko Takamine and Hiroshi Nihonyanagi

This Toho production is based on a novel published the same year by Yasunari Kawabata, who in 1968 became the first Japanese writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. The novel is not regarded as one of his major works and has yet to be translated into English (although there have been translations in German and Spanish) and it should be noted that Kawabata also wrote a famous story entitled The Dancing Girl of Izu, which is entirely unrelated to this one. The screenplay was written by Kaneto Shindo, who may be the most prolific screenwriter of all time with over 200 credits, but is best known as the director of Onibaba, Kuroneko and The Naked Island. He appears to have made a few changes to the original, some of which may be explained by the fact that films still had to be approved by the occupying Americans in 1951 (presumably not too difficult in this case as Dancing Girl promotes Western culture while also including some anti-war dialogue). The platonic nature of the relationship between Namiko and Takehara appears to have been the same in the original, but the Buddhist theme of the novel is largely absent and there is no mention of Takao’s flirtation with communism or Takehara being married. Unfortunately, Shindo chose to write a new scene in which Shinako visits her former ballet teacher on his deathbed – this scene is incredibly corny and easily the worst bit in the film.

So Yamamura and Mieko Takamine

So Yamamura and Mieko TakamineThis sequence aside, director Mikio Naruse does a fine job, appropriately staging many scenes so that his characters have their backs to each other, which serves to emphasize their emotional distance. Ichiro Saito’s Western-style, string-laden score should perhaps have been used more sparingly, although it could be argued that it matches the maudlin tone of the film. The cast are solid across the board and it’s interesting to see Mariko Okada in her film debut even if she was obviously doubled for most of the ballet sequences. Okada would go on to rival Ayako Wakao as one of Japan’s top film actresses and, although her performance here may not quite have the subtlety of her later ones, she acquits herself pretty well in a major role that must have been daunting for an 18-year-old who had been signed as a ‘Toho New Face’ just 20 days before this film went into production.

August 13, 2023

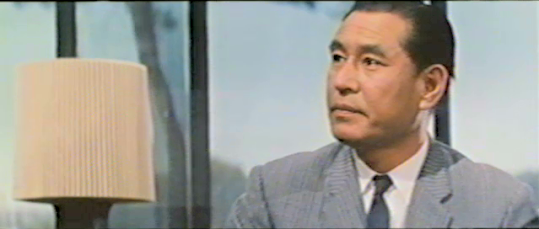

The Hunting Rifle / 猟銃 / Ryoju (1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #73

Mariko Okada

Mariko OkadaSaiko (Fujiko Yamamoto), the wife of Kadota, a young doctor (Keiji Sada), receives an unexpected visit one day from Hamako (Nobuko Otowa), an emotionally unstable woman accompanied by a 5-year-old girl she claims to be Kadota’s daughter. Hamako dumps the girl, Shoko, on her, saying she is no longer able to raise her by herself and Shoko is Kadota’s responsibility. Shortly after leaving, Hamako commits suicide. Feeling sorry for Shoko, Saiko decides to raise her as her own, but cannot forgive her husband his infidelity and insists on a divorce.

Fujiko Yamamoto

Fujiko YamamotoSometime later, Saiko goes to visit her newly-married cousin, the 20-year-old Midori (Mariko Okada), and meets her much older, pottery-fancying husband, Misugi (Shin Saburi), for the first time. Misugi tricks Saiko into going for a walk alone with him, which leads to a long-running affair. Eight years passes, and Misugi and Saiko still have no idea that Midori has known they’ve been cheating on her almost from the beginning but has chosen to remain silent…

Keiji Sada

Keiji SadaThis Shochiku production is quite a free adaptation of Yasushi Inoue’s highbrow 60-page novella first published in 1949. The original story is introduced by a narrator who has been contacted out of the blue by a hunter (Misugi) after the latter realised that he must have been the inspiration for a man portrayed by the poet in one of his works. Misugi sends him a letter from each of the three women in his life, and it is these letters through which the rest of the story unfolds. Such a literary device was obviously not going to work for the cinema, so it was understandably dropped by screenwriter Toshio Yasumi, who had already collaborated on half a dozen other films with this film’s director, Heinosuke Gosho (and would go on to write a terrific screenplay for Shiro Toyoda’s Portrait of Hell). However, despite the fact that several scenes are replicated faithfully, much of the character motivation evident in the novella is not put across well here.

Shin Saburi upstaged by a lamp

Shin Saburi upstaged by a lampIndeed, The Hunting Rifle features perhaps the most implausible seduction scene in cinema history when Misugi, having known Saiko for what seems like five minutes, poses the question, ‘Being obsessed with Joseon white porcelain is alright, so why shouldn’t I be obsessed by you?’, which is apparently all it takes for her to melt into his arms. In the book, this is not really a ‘scene’ at all, and so is not an issue, especially as Saiko goes on to explain her motivation. Another clumsy moment occurs in the film when Misugi gives Shoko (now played by Haruko Wanibuchi) a book for her 16th birthday, explaining that the contents are all about love. This comes across as inappropriate and creepy here, but not so in the book, in which there is no explanation from Misugi. The filmmakers also neglect to make use of a memorable visual image that occurs in the original when Saiko visits a university and is disturbed by some snake specimens she sees preserved in jars. This leads Misugi to observe that ‘Everyone’s got a snake in him,’ a sentence which haunts Saiko, who comes to believe herself at the mercy of a persistent self-destructive urge which she visualises as a snake coiled in her belly. In the film, we don’t get the scene with the specimens, so the talk of snakes seems merely whimsical. Furthermore, the symbol of The Hunting Rifle itself goes for very little in the film, whereas in the story it is made quite clear that it represents man’s essential loneliness.

Nobuko Otowa

Nobuko OtowaAnother problem with Gosho’s film is the casting, especially that of Shin Saburi. In his hands, Misugi is not only physically unattractive but completely uncharismatic, making Saiko’s helpless attraction for him baffling. Fujiko Yamamoto is a fine actress, but does not seem at all the sort to stab her cousin in the back, and her somewhat mask-like features are perhaps not the best at expressing complex emotions. It’s the more expressive Mariko Okada who takes the acting honours here – when the story jumps forward by eight years, Midori has changed from a rather naïve, gauche young thing to a sophisticated woman with considerable poise, and Okada not only handles this transformation very well, but is great at revealing the hidden thoughts of her character with a subtle look. The other notable names in the cast – Nobuko Otowa and Keiji Sada – are featured surprisingly little considering their status, but do their usual good work. But the casting of Sada also works against the film – imagine a woman leaving Keiji Sada because he had an affair and then rushing off to have an affair of her own with Shin Saburi!

I found this a real disappointment from director Heinosuke Gosho, whose films are generally good to excellent (I’d especially recommend An Inn at Osaka and An Innocent Witch). Although Inoue’s novella was unsuited to the screen in the first place, that certainly does not excuse all the poor choices here, which also include the truly awful string-laden music score complete with repeated harp glissando that heavily underlines every emotional moment. This is reminiscent of Hollywood at its corniest, and something I found especially grating as I watch Japanese films of this period partly to get away from all that. The culprit, Yasushi Akutagawa, has done good scores too, and I’ve noticed that the work of many Japanese film composers in particular seems to vary a great deal in quality, though I’m unsure why. Anyway, combined with the ham-fisted adaptation and ill-advised casting, the music makes The Hunting Rifle an almost total misfire for me, with only Mariko Okada hitting the target.

August 6, 2023

Magistrate of the Floating World / 着ながし奉行 / Kinagashi bugyo (‘The Magistrate who Dresses Informally’, 1981)

Obscure Japanese Film #72

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya NakadaiThis Fuji TV movie is a period comedy-drama directed by none other than Kihachi Okamoto and starring his frequent leading actor Tatsuya Nakadai. Koheita Mochizuki (Nakadai) is the new magistrate appointed to clean up Horisoto, a town district on a small island connected to the rest of the town by a single footbridge. Criminals operate freely there, and the town has lost three magistrates in the space of a year due to their inability to deal with the situation. Mochizuki is an eccentric character who takes a radically new approach and decides it is better to be underestimated. Before his arrival, he has somebody spread a rumour that he is better at cavorting with women than he is at martial arts. In fact, although he is a womaniser, he is also a martial arts expert. The staff are awaiting his arrival at the magistrate’s office, but he arrives incognito, avoids the office and begins making friends with the criminals…

If the idea of a crime-riddled island sounds familiar from Inn of Evil, this is no coincidence as Magistrate of the Floating World is also based on a story by Shugoro Yamamoto (‘Machi bugyo nikki’, or ‘Town Samurai Diary’). There’s a clever narrative device in use in this version, which has the main action interspersed with scenes featuring a dialogue between two scribes awaiting the arrival of Mochizuki at the office. Functioning almost like a Greek chorus, these two characters discuss the situation throughout and provide useful exposition.

Kihachi Okamoto also co-wrote the script (with Toshiaki Matsushima), but this was apparently a troubled production as he treated it like a feature film and became so fed up with constantly being told he could not do certain things due to budgetary constraints that at one point he threatened to quit. Considering this, the final result turned out pretty well and I feel that it’s not only better than most of Okamoto’s post-1960s work, but also superior to Dora-heita (2000), Kon Ichikawa’s lacklustre later version based on a screenplay by himself, Keisuke Kinoshita and Akira Kurosawa (written around three decades before the film was finally made). It’s not always as funny as Okamoto seems to think, but it’s dynamic and fast-moving enough that the weaker comic moments are soon forgotten.

Nakadai is clearly enjoying himself here in a rare comic role, while other notables among the cast include Eitaro Ozawa and Taiji Tonoyama, the latter as the sidekick constantly reminding Mochizuki to wash his hands. Also featured are several students from Nakadai’s acting school, including Koji Yakusho, who later starred as Mochizuki in Dora-heita. Other adaptations of Yamamoto’s story include Kenji Misumi’s 1959 version starring Shintaro Katsu and Eiichi Kudo’s 1987 film with Ken Watanabe.

Thanks to Samurai Vs Ninja for making this available on YouTube here.

July 29, 2023

The Way of Drama / 芝居道 / Shibaido (1944)

Obscure Japanese Film #71

Kazuo Hasegawa

Kazuo HasegawaSet during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, this Toho production stars Kazuo Hasegawa as Shinzo, a young stage actor in Osaka whose newfound popularity playing military heroes has gone to his head. He has a sweetheart, Hanaryu (Isuzu Yamada), a shamisen player he is planning to marry, but his master, Heikichi (Roppa Furukawa), thinks he has become too arrogant and will never succeed in the long-term if he allows himself to be distracted by marriage. Heikichi decides to ask Hanaryu to break off the relationship for Shinzo’s own good…

In his film The Song Lantern from the previous year, director Mikio Naruse had managed to avoid making military propaganda, but by this point it was a case of either spread the message the authorities wanted to put across or don’t make a movie. The Way of Drama was adapted by the prolific Toshio Yasumi based on a novel by Koen Hasegawa (1904-77). It’s unclear whether the propaganda aspect was present in the original, but the film certainly contains a rather obvious message about the importance of self-sacrifice. The character of Heikichi, the theatre director, is portrayed as a very noble man because he puts on plays about heroic soldiers and keeps ticket prices low so that as many people as possible will learn that the goal of destroying the enemy is far more important than one’s own paltry little life. Of course, this is unlikely to strike a chord with many viewers nowadays, but if we can ignore this aspect of the film, there are some pleasures to be found in the fine performances of Hasegawa and Yamada. Incidentally, the one scene in which Hasegawa is really bad is the opening scene in the theatre, where he plays a mortally wounded soldier delivering his patriotic last words as he expires – could Hasegawa and Naruse have been subtly taking the rise out of the military here?

The supporting cast is also strong and features Takashi Shimura as a rival theatre director, Ranko Hanai as Heikichi’s cheerful daughter and Eitaro Shindo as a seasoned elder thespian. Directed by Naruse, it goes without saying that The Way of Drama is well-made, although working under the constraints and with the limited resources that he was at the time, it is obviously not one of his best.

July 22, 2023

Woman Walks the Earth Alone / 女ひとり大地を行く / Onna hitori daichi o yuku (1953)

Obscure Japanese Film #70

The story begins in 1932. Sayo (Isuzu Yamada) and Kisaku (Jukichi Uno) are a married couple with two young children living in Akita Prefecture. Times are hard and they are struggling to make ends meet. Kisaku decides that the only thing for it is to go off to Hokkaido and work in the coal mines. He very quickly realises his mistake when he witnesses a co-worker being tortured to death by a supervisor. Kisaku decides to run away, but on the day of his escape there’s an explosion at the mine and he is presumed to be among the fatalities.

Hearing nothing from her husband, Sayo travels to Hokkaido with her children, where she is informed of his death. She decides to stay on and work as a miner herself. Eventually, she becomes involved with a male co-worker, Kaneko (Isao Numasaki), but he is drafted into the army and killed in World War 2. After the war, the harsh military regime rapidly collapses and conditions at the mine improve a little, enabling Sayo to get an easier job sorting the coal away from the mine. Her eldest son, Kiichi (Jinkichi Orimoto), hates the life of a coal miner and runs off with a nurse, Fumiko (Yoshiko Sakurai), while her younger son, Kiyoji (Taketoshi Naito), joins the union and starts going out with Takako (Hatae Kishi), but becomes involved in a conflict with her father, who has been collaborating with the bosses.

Given the subject matter and the fact that one of the screenwriters is Kaneto Shindo, it will be no surprise to learn that this is a very left-wing film. Like some of Satsuo Yamamoto’s similarly-oriented films of the same period, it was made outside the studio system with money raised from thousands of union members each making a small contribution. The production company responsible, Kinuta Productions, had been established with funds paid by Toho Studios to the Japan Film and Theatre Workers’ Union in settlement of a legal dispute. Kinuta Productions had already made Haha nareba onna nareba (something like ‘A Mother is also a Woman’) the previous year, also starring Isuzu Yamada and directed by Fumio Kamei (1908-87). Kamei was a radical who had studied in the Soviet Union and subsequently worked at Toho before the content of his work had angered the Japanese authorities, who actually put him in prison for some time as a result. He also made documentaries, but the fact that he had to work outside the studio system due to his politics seems to have restricted his output more than it did that of his friend Satsuo Yamamoto, partly because Woman Walks the Earth Alone was a commercial failure.

As the film was shot on location, the cast and crew stayed with local coal mining families, lending authenticity, but perhaps partially explaining the lack of well-known names among the cast. Aside from Isuzu Yamada and Jukichi Uno, the most familiar faces are probably Kon Ichikawa favourites Tanie Kitabayashi (as a friend of Sayo’s) and Jun Hamamura, the latter in an uncharacteristic role as a bullying supervisor. Although Yamada is the ostensible star, the film spends a lot of time with its other characters and her role is not one of her most memorable. One reason the film is not better known may simply be because, as a non- studio picture, it has fallen through the cracks somewhat, but it would also be difficult to claim this as a forgotten masterpiece. Some of the characters are too one-dimensional, the ending is sentimental, and it occasionally lapses into melodrama, with the brutality of the supervisors particularly being overdone and straight out of the playbook of Soviet propaganda cinema.

Originally, the film ran at 164 minutes, but an organisation known as the Film Ethics Committee (or ‘Eirin’ for short) objected to the references to the Korean War, and this was apparently the reason why it was cut to 132 minutes (the pressure to increase coal production that leads to the miners’ protest towards the end of the film was originally attributed to aiding the U.S. military in the Korean War, in regard to which Japan was officially neutral). The shorter version is the one I have seen and I feel that it would probably have more impact in the longer cut (which, happily, still survives, although is yet to be released on home video).

July 15, 2023

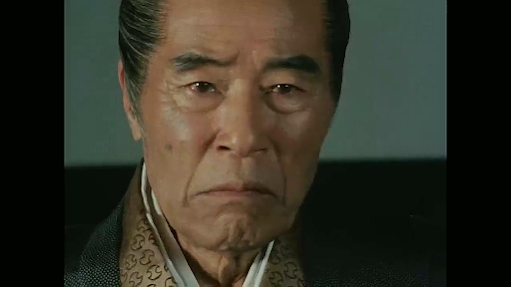

The Fir Tree Remains /樅ノ木は残った / Momino ki ha nokotta (1983)

Obscure Japanese Film #69

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya NakadaiIn this Fuji TV movie, Tatsuya Nakadai stars as Kai Harada (1619-71), a samurai magistrate involved in the Daté Uproar (aka the Kanbun Incident), a factional squabble which erupted into violence when the young head of the Daté clan, Tsunamune Daté, was exiled as a punishment for debauchery and replaced by a 2-year-old. It was rumoured that Tsunamune’s punishment was a ruse by the shogunate, who wanted to weaken the power of the feudal lords.

The Fir Tree Remains is based on an untranslated novel of the same name by Shugoro Yamamoto, a favourite writer of Akira Kurosawa, whose films Sanjuro, Red Beard and Dodes’ka-den were all based on Yamamoto stories. Yamamoto was also a favourite of Yasuko Miyazaki, the former actress who married Tatsuya Nakadai and later became a screenwriter under the name of Tomoe Ryu. Her first script had been a television adaptation of Yamamoto’s Tsuri shinobu back in 1966, while her screenplay for Masaki Kobayashi’s Inn of Evil was based on another of his novels, which she re-adapted for television in 1982 as Jigoku no okite and later as a stage play.

Here we have a complex story to tell in 90 minutes and one that I can’t say I found terribly engaging, although it’s certainly got a few things going for it. One of several period dramas Nakadai made for television under the direction of Akira Inoue around this time, for a 1983 TV movie, it’s surprisingly well-lit and photographed. The acting is also pretty decent on the whole, with Nakadai’s confident restraint being especially effective as the unflappable Kai Harada, who – like the fir tree in his garden – keeps his own counsel while those around him are (literally) losing their heads. According to Japanese Wikipedia, Harada had usually been depicted as a scheming villain prior to Yamamoto’s story; here, he’s portrayed as a sympathetic character with pure motives.

Also popping up among the cast are Eitaro Ozawa, one of Nakadai’s acting teachers from his student days, and a young Koji Yakusho, one of his students from his teaching days.

Some of the music’s a bit clichéd and the subtitles are sometimes a bit odd (“I am sorry about this ruckus. Go away please.”), but on the whole I’d say this is worth a look for Nakadai fans.

Yamamoto’s novel had previously been filmed for the cinema in 1962 by Kenji Misumi under the title Aobajo no oni (Aoba Castle Demon) in a version starring Kazuo Hasegawa, while other television adaptations were made in 1964, 1970 (with Mikijiro Hira), 1990 and 2010.

Thanks to Samurai vs. Ninja for making this available on YouTube here.