M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 18

March 4, 2023

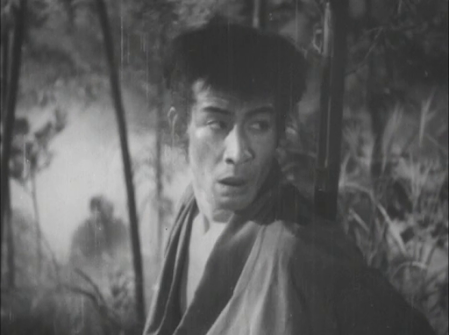

Hirate Miki / 平手造酒 (1951)

Obscure Japanese Film #49

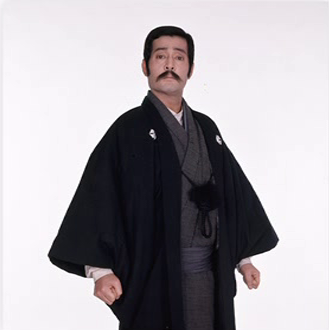

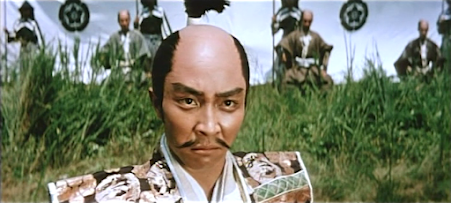

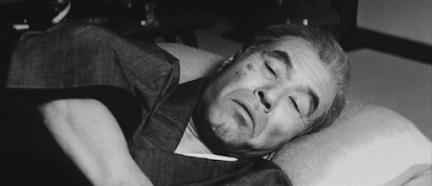

Ranko Hanai

Ranko Hanai

Hirate Miki (c.1814-1844) was a swordsman who became a bodyguard for a yakuza boss and died in a fight with a rival gang. There were numerous films about him throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, but these abruptly ceased at the time that Japan entered WW2, presumably because Miki was killed at a young age and his story would have been seen as defeatist. His first reappearance in a movie after the war was as a supporting character in Shintoho’s Tenpo suiko-den: Otone no yogiri (1950), in which he had also been played by So Yamamura, the star of this film.

Hirate Miki is reminiscent of Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata(1943) in that the heroes of both are martial arts experts who undergo a spiritual crisis which causes them to stray from the path of righteousness before they finally redeem themselves. Aside from the choice of martial art and the lighter ending of Kurosawa’s film, the main point of difference between the two works is that Miki, as played by Yamamura, is an unlikeable and charmless character; ‘He must have quit smiling in the womb!’, one character aptly comments. Yamamura seems an odd choice as he was already 41 when this was made and is clearly too old for the role.

Miki starts out as an idealistic young man whose skill sees him move quickly up the ranks. However, he is frustrated in his romantic ambitions and becomes bitter about the importance of money and status. One night, he gets drunk, trashes a restaurant and loses a lucrative new position as a result. Admonished by the head of his dojo, he nevertheless continues to be insufferable, frequently beating the crap out of his poor students with his bamboo practise sword. Eventually, he runs off with a geisha, Masuji (Ranko Hanai from Kurosawa's Sanshiro Sugata). She is another disappointed idealist, having worked hard for years to become a top shamisen player only to find that her male clients have little interest in that particular skill. Meanwhile, Miki falls ill with tuberculosis and ends up working for a yakuza boss. There’s a splendidly ironic moment when Miki begins coughing up blood after slaying a bunch of rival gang members; his friend, standing amid the corpses, finally decides the moment has come to shout for a doctor.

The narrative of the film is rather choppy to say the least – hardly surprising as the version I saw ran 64 minutes, and it seems there was originally a longer 107-minute version. With 43 minutes missing, it’s not really possible to judge this film fairly in my opinion, but what remains is certainly worth a look for the fine cinematography (by Kikuzo Kawasaki) and a number of nice touches, such as the paper crane made by Masuji which finally softens the heart of old misery-guts Miki.

Further Kurosawa connections include a cameo by eccentric geriatric-specialist Bokuzen Hidari as a priest and the fact that this was the second script by the great screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto to be filmed (Rashomonbeing the first). Director Kyotaro Namiki does fine work here but is remembered, if at all, for a couple of horror films he made towards the end of his career, The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty (1957) and Vampire Bride (1960).

February 24, 2023

Sanshiro Sugata / 姿三四郎 (1977)

Obscure Japanese Film #48

Tomokazu Miura and Kumiko Akiyoshi

Tomokazu Miura and Kumiko Akiyoshi

Sanshiro Sugata (1943) was, of course, the directorial debut of a certain Akira Kurosawa, who had persuaded Toho Studios to buy the rights to Tsuneo Tomita’s just-published novel of the same name. Sugata is a fictional character based on Shiro Saigo (1866-1922), an early practitioner of judo who became one of the masters of the art. Tomita himself was the son of another judo champ, Tsunejiro Tomita, who had been an associate of Saigo’s. Kurosawa’s commercial instincts had proven sound on that occasion – so much so, in fact, that the studio pressured him into making a sequel, which was released just as the war was coming to an end. Between that film and this 1977 version, there had been a further four remakes, including a 1965 film produced by Kurosawa himself. This was apparently a scene-for-scene remake of the first two films, but it was not well-received by the critics and seems to have all but destroyed the career of its young director, Seiichiro Uchikawa, whose previous film (Samurai from Nowhere) had shown definite promise.

Kihachi Okamoto (right) on set

Kihachi Okamoto (right) on set

Kihachi Okamoto was an eccentric and often brilliant director whose work suffered a sharp decline in quality as the ‘60s ended and the ‘70s began. The reasons for this are debatable, but in my opinion none of his films from 1970 onwards really work, and his talent became less and less evident as time went on. This is a pity, because his mid-period movies such as Sword of Doom, Oh Bomb! and The Human Bullet are stunning. Unfortunately, his remake of Sanshiro Sugata (newly released on DVD in Japan) proves not to have been a return to form. In fact, it copies a great deal from the Kurosawa original, from the blurry point-of-view shot seen through the eyes of a nearly knocked-out opponent to the climactic fight on the windswept hill. There is one scene in which Okamoto subverts our expectations – in the original, Sugata had thrown away his geta (wooden sandals) when volunteering to drive judo master Shogoro Yano’s rickshaw; Kurosawa had used this to create a striking montage sequence in which we see what happens to one of the geta with the passage of time. In Okamoto’s version, he is about to throw them away, but thinks better of it and ties them to the rickshaw handle. Some of the fight scenes could be said to be an improvement on Kurosawa’s, but the shot of an opponent flying through the air worked in 1943 because it was so brief, whereas Okamoto makes it completely absurd by extending the shot and adding a ridiculous sound effect. Indeed, this Sanshiro Sugata, with its pop song theme tune, jaunty score and broad performances suggests that the intended audience was 10-year-old boys. Incidentally, the lame music is by none other than Masaru Sato, who had once given us one of the great film scores of all time for Kurosawa’s Yojimbo.

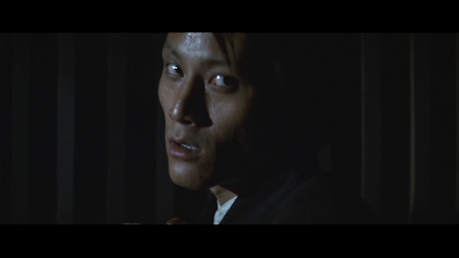

That Okamoto assembled an all-star cast mostly goes for very little. Tatsuya Nakadai is fine as Sugata’s teacher, Shogoro Yano (played by Toshiro Mifune in 1965), but it’s hardly one of his better roles. Nevertheless, he clearly did some of his own stunts and looks more convincingly formidable than Denjiro Okochi did in the 1943 film. We also get Kumiko Akiyoshi as the love interest, Tomisaburo ‘Lone Wolf’ Wakayama as her father (Takashi Shimura in the original), Kyoko ‘Woman in the Dunes’ Kishida as an older woman who tries to seduce Sanshiro, Atsuo Nakamura as Gennosuke Higaki (the main villain of the piece), Kunie Tanaka as Sanshiro’s best friend and Tetsuro Tanba in an especially thankless role as a senior member of Yano’s school.

Nakadai’s real-life acting student Daisuke Ryu also makes his film debut as one of the attackers whom Nakadai hurls into the canal. The lead is played by the boyish Tomokazu Miura, a teen heartthrob type who could act a bit; he’s adequate, but never really convinces as a man of the 19th-century and I prefer Susumu Fujita in the original.

Kunie Tanaka, Akiyoshi and Miura

Kunie Tanaka, Akiyoshi and Miura

The film was mostly shot with a handheld camera long before it became de rigeur, but I can’t say it adds much and it’s really only the fact that it’s in Panavision that prevents this looking like a TV drama. The screenplay was co-written by Okamoto and Nakadai’s wife, Yasuko Miyazaki. The first hour and 40 minutes follow the first Kurosawa film, while the final 40 minutes feature the karate-schooled brothers of Gennosuke Higaki who are out for vengeance and appeared in Kurosawa's 1945 sequel. The role of the heroine has been greatly expanded (the character was little more than a cipher in Kurosawa’s films) and the new character of Sanshiro’s best friend is given quite a few scenes, in one of which he is brutally attacked by Gennosuke Higaki and left with a permanently twisted arm. No longer able to fight, he later turns up with a gun! One wonders if this role was created especially for Kunie Tanaka, who must have been double-jointed as his broken limb is so convincing and is, in fact, the highlight of this otherwise disappointing movie.

Watched without subtitles.

February 15, 2023

Kemono no tawamure / 獣の戯れ/ The Frolic of the Beasts (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #47

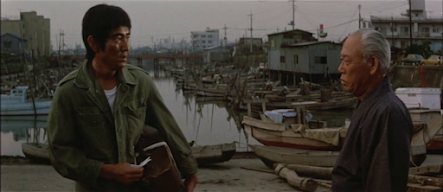

Koji (Takao Ito) is a student working at a ceramics shop in Tokyo owned and run by middle-aged author Ippei, a writer of highbrow literature (Seizaburo Kawazu). Despite having a beautiful younger wife, Yuko (Ayako Wakao), Ippei is also a philanderer who condescendingly boasts of his affairs to Koji. However, the shoe is soon on the other foot when Koji begins an affair with his boss’s wife…

One evening, Koji escorts Yuko home only to discover that Ippei is there in bed with a stripper. When Yuko protests, Ippei slaps her around, causing Koji to lose his temper. He pulls out a wrench he happened to have in his pocket and attacks Ippei with it. Ippei survives, albeit in a brain-damaged state, while Koji goes to prison.

Meanwhile, Yuko breaks with convention and becomes Koji’s sponsor, enabling him to be released into her care after serving two years. She is now living with the disabled Ippei in a coastal village on the Izu Peninsula, running a flower farm where Koji will work. This strange triangle results in an emotional hothouse which can only end in tragedy.

This brief synopsis simplifies the non-linear narrative of both the film and the book it is based on, a short 1961 novel by Yukio Mishima which finally appeared in English translation in 2018. Screenwriter Kazuo Funahashi (1919-2006) also wrote the screenplays for Listen to the Voices of the Sea (1950), The Temple of Wild Geese (1962) and another Mishima adaptation, Sword (aka Ken, 1964). His adaptation is pretty faithful to the book, although some of the subtle psychological nuances are inevitably lost, resulting in a slightly more conventional melodrama than the original. For example, when Koji finds the wrench, he conceals it from Yuko in the book, but not in the film as, without the insight into Koji’s mind that the text provides, this would have made it appear that his attack on Ippei was premeditated. According to translator Andrew Clare, Mishima’s original is also filled with references to the Noh theatre, but whether this would have been apparent to the average reader or viewer even in Japan is questionable.

The other main departure from the novel is the ending. This is more surprising given that the story originally ended with Yuko, but for some inscrutable reason the filmmakers chose not to give the final scene to their star. Incidentally, Ayako Wakao had acted opposite Mishima in Yasuzo Masumura’s Afraid to Die a few years earlier and was an actress that the author – an avid moviegoer – greatly admired. She later appeared in both stage (1970) and film (2005) versions of his novel Spring Snow.

Aside from Wakao, the most familiar member of the cast is Masao Mishima, who pops up as a much more benevolent priest than the one he played in The Temple of Wild Geese. However, Seizaburo Kawazu (1908-83), who plays Ippei, had a long career in the movies stretching back to 1928 and appeared in Yojimboas the gang boss Seibei. In what was probably one of his best later roles, he’s very good here playing a character who undergoes a dramatic change.

The subtle music is the third and final film score by avant-garde composer Yoshiro Irino (1921-80), whose contribution to the picture is tastefully sparse and restrained, while the director, Sokichi Tomimoto (1927-89), is about as obscure as it gets. He was a Daiei contract director forced into TV work a few years after this and few of his films are accessible. On this evidence, he certainly had some talent at least as the film is well-staged and shot throughout even if there is little evidence of a particularly individual style. The following year, he worked with Wakao again on a Seicho Matsumoto adaptation, Forest without Flowers, which I for one would love to see.

Watched without subtitles.

February 6, 2023

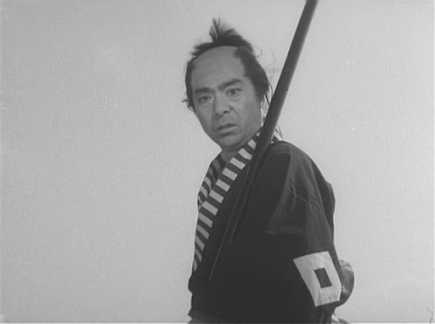

Gero no kubi /下郎の首 /'Gero's Head' (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #46

Michiko Saga and Jun Tazaki

Michiko Saga and Jun TazakiWriter-director Daisuke Ito’s remake of his own 1927 film Gero(since lost) is a period drama (or jidaigeki) made for Shintoho.Jun Tazaki stars as Geru, a manservant whose master (Minoru Takada) is killed as a result of an argument during a game of go. Geru was fishing with the master’s adult son, Shintaro (Akihiko Katayama), at the time of the incident. By the time they return, the unnamed killer (Eitaro Ozawa) has fled the scene, but they learn that he has nine moles on his face. Geru and Shintaro set off on a quest to find the murderer, but Shintaro falls ill and Geru is forced to become a busker, performing spear dances to support them both.

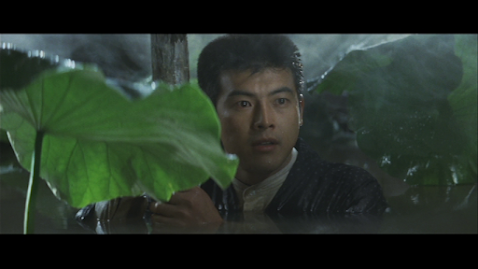

One day, sheltering from the rain outside a house, Geru is lent an umbrella by the inhabitant, Oichi (Michiko Saga, daughter of Isuzu Yamada and star of The Mad Fox), and a friendship develops when he comes to return it. Geru learns that Oichi is the concubine of a man named Sudo. During a later visit, Sudo unexpectedly returns and Geru is shocked to discover that he’s the man with nine moles on his face…

In Japanese cinema history, Daisuke Ito – who made his first film in 1920 – is known as the father of the period drama, and there is no doubt that he was an innovative and hugely influential filmmaker. One of his few surviving silent films, Jirokichi the Rat (1931) remains impressive today. Geru no kubi is an extremely well-directed film in the way Ito stages his scenes, co-ordinates the actors, focuses on surprising details and uses dynamic crane and dolly shots combined with strong compositions and depth of field. Ito can be amazingly bold, too; in one scene during a voiceover, he fills the screen with a shot of a blank piece of paper and holds the shot for over two minutes!

On the basis of this film and the other Ito works I’ve seen, in my opinion Ito’s weakness is that he sometimes either allows or encourages his actors to go over the top. There’s a running ‘gag’ here in which Gero’s legs go dead every time he has to kneel for a while, meaning that he’s unable to walk properly when he gets up. This clumsy slapstick is unfortunate in a film which is otherwise pretty sober in tone even if it lacks the depth to make it a true classic. However, the un-Hollywood like preference in Japanese cinema for a tragic ending is certainly well-catered to and comes after a grand climax in which we finally get a generous helping of chanbara (sword-fighting) action, albeit of the (presumably deliberately) clumsy variety.

Also among the cast are the scene-stealing Koji Mitsui in a Lon Chaney-like role as a fake paraplegic beggar and Tetsuro Tanba as a passing samurai Geru and Shintaro manage to offend. The impressive cinematography is by Yoshimi Hirano, who also shot The Life of Oharu (1951). Jun Tazaki is decent enough in the lead, but a little lacking in star quality. However, the film's qualities far outweigh its flaws and Gero no kubi is a good example of why Daisuke Ito's work should be much better known than it is today.

Watched without subtitles.

The original was based on a story by one Tokichi Nakamura, who is for some reason uncredited on this version.

January 30, 2023

The Lost Alibi aka The Black Book: An Employee’s Confession/ 黒い画集 あるサラリーマンの証言 / Kuroi gashu: Aru sarariman no shogen (1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #45

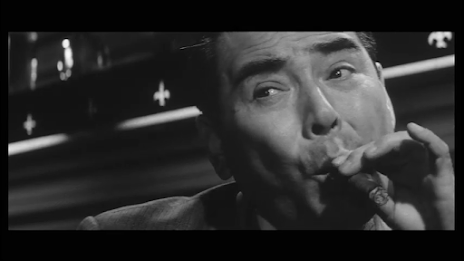

Keiju Kobayashi

Keiju Kobayashi

Based on a 1958 Seicho Matsumoto short story entitled Shogen(‘Testimony’) published as part of his ‘Black Art Book’ (Kuroigashu) series, this crime drama stars Keiju Kobayashi as Ishino, a procurement manager for a fabric company. The film spends the first 8 minutes showing us how uninteresting the life of this faceless executive and family man is before revealing his secret – not only does he have a mistress, but the pretty young female in question is an employee who works under him. Chieko (Chisako Hara), is a bubble-headed good-time girl living in a love nest paid for by Ishino. Given the fact that Ishino has a sweet-tempered and still-attractive wife (Chieko Nakakita) as well as two children, he really has no justification for his behaviour, but he seems to have no qualms as long as he’s able to keep it secret and avoid losing face. Leaving Chieko’s apartment after one of his evening visits, he bumps into a neighbour, Sugiyama (Masao Oda), who works as a door-to-door salesman. When Sugiyama becomes a murder suspect, his only alibi is the chance meeting with Ishino, who is extremely reluctant to admit having seen him as he believes it may expose his philandering…

The story takes some ingenious twists and turns which are all the more effective for being quite plausible. The excellent script is by Shinobu Hashimoto, who collaborated with Kurosawa on numerous occasions, wrote the screenplay for Hara-Kiri (1962) and skilfully adapted the work of Satsuo Matsumoto for a number of films directed by Yoshitaro Nomura.

The cast is uniformly good, and also features Ko Nishimura as the detective on the case and Kin Sugai as Sugiyama’s wife. A specialist in downtrodden characters, in one scene she breaks down and begs Ishino for help in an exhibition of raw emotion so powerful it’s uncomfortable for the viewer as well.

The star of the film, Keiju Kobayashi, was best-known in Japan at the time for salaryman comedies, so his casting here is interesting in the way it subverts his usual image, as would Kihachi Okamoto’s Elegant Life of Mr Everyman (1963) in a rather different way. He was also an excellent dramatic actor whose other notable performances include Happiness of Us Alone (1961), in which he and Hideko Takamine portrayed a deaf-mute couple with admirable sensitivity, and his cameo as the samurai locked in the cupboard in Sanjuro. Kobayashi had already scored a hit for this film’s director, Hiromichi Horikawa, in The Naked General (1958), for which Kobayashi had won a Best Actor Award. The two would go on to collaborate on a number of further occasions, including on Shiro to kuro (1963), a film not dissimilar to this one and which involved many of the same people. Horikawa described Kobayashi as ‘an irreplaceable actor whose extraordinary performances burst out from an extremely ordinary person.’ Horikawa himself was highly rated by Akira Kurosawa, for whom he had often worked as an assistant director and, on the basis of The Lost Alibi and Shiro to kuro, Horikawa is the Japanese director whose work I would most like to be able to see more of.

The Lost Alibi appears to have been pretty successful and spawned several TV remakes, including a 1965 version starring Rentaro Mikuni. In the case of Horikawa’s version, there is more to it than just a clever crime drama. While not explicitly discussed, Japan’s post-war trauma is evident throughout, the characters embodying the moral vacuum the country seemed in danger of becoming after the seismic cultural shock of defeat, the atom bomb and the American occupation, all of which challenged the people’s long-held values and in some cases led them to embrace materialism or lead lives of hedonistic excess. In this example, the character of Ishino is so far gone that it is made quite explicit at the end of the film that he merely considers himself to have been unfortunate and has learned precisely nothing – a discomfiting ending, to say the least.

January 24, 2023

The Threat / 脅迫 おどし / Odoshi (1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #44

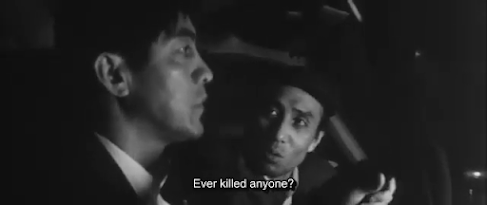

Rentaro Mikuni and Ko Nishimura

Rentaro Mikuni and Ko Nishimura

This Toei production begins with a wedding scene reminiscent of the one which opens The Bad Sleep Well. Misawa (Rentaro Mikuni), a sales manager, has arranged a sham marriage between his boss’s mistress and an employee in order to cover up said boss’s philandering. During his speech, Misawa lays it on a bit thick singing the praises of the newlyweds. On the face of it, this beginning has nothing to do with the rest of the movie. However, it is significant in that it reveals an important aspect of Misawa’s character – he is by nature a collaborator, a man only too willing to be used.

Hideo Murota and Ko Nishimura

Hideo Murota and Ko Nishimura

Soon after the wedding, Misawa finds his home invaded by two escaped convicts who have kidnapped a baby and need a place to hide out for a night or two until they can collect the ransom and flee Japan by boat. The two men are the small but cunning Kawanishi (Ko Nishimura) and his dim sidekick, Sabu (Hideo Murota). Both Misawa and Kawanishi were soldiers during the war but, unlike Kawanishi, Misawa has no experience of killing, so Kawanishi considers him a coward for keeping his hands clean and enjoys tormenting him for this reason. At one point, he snorts contemptuously, ‘You’ve probably never even raped a woman!’ When coerced into helping Kawanishi collect the ransom money, Misawa seems only too keen to oblige and does more than he is asked, apparently out of cowardice. These scenes are made even more pitiful to watch due to the disparity in size between these two terrific actors – it’s like seeing a German Shepherd being bullied by a Chihuahua. The suspense in the film mainly comes from waiting to see whether Misawa will finally grow a pair and stand up to the intruders.

I remember once reading somebody describe Tatsuya Nakadai as the Japanese Brando. Personally, I don’t consider that a very accurate comparison as Nakadai is no method actor and his style seems quite different to me. But you could certainly make a case for Mikuni as the Japanese Brando – his approach was far more method than Nakadai’s and, like Brando, he never bothered to try and court the audience’s sympathy. In this film, he takes a beating to rival the one dished out to Brando in The Chase. In another scene, he lays into his wife. As Mikuni was famous for taking realism to extremes, it may have been difficult to cast the female lead here, which is well played by the slightly dumpy Masumi Harukawa (star of Shohei Imamura’s Intentions of Murder). In fact, the cast is rock solid all round and it’s also nice to see Kunie Tanaka pop up as a dopey policeman.

Kunie Tanaka and Masumi Harukawa

Kunie Tanaka and Masumi HarukawaDirector Kinji Fukasaku went on to enjoy a long and successful career, of course, and on this evidence it’s not hard to see why as it's all very well staged and shot, especially the action scenes. He also co-wrote the screenplay and it’s the attention to psychology which really makes this film a cut above the average thriller.

At the time of writing, the film can be viewed on YouTube here.Mikuni had actually attempted to evade the draft during the war. Though unsuccessful, he served as a soldier without ever firing his gun. Nishimura, on the other hand, had been a kamikaze pilot but survived after his mission was cancelled.

December 11, 2022

Beast Alley / けものみち / Kemono michi (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #43

Junko Ikeuchi

Junko Ikeuchi Based on a novel by prolific social realist crime writer Seicho Matsumoto, Beast Alleyis a Toho production directed by Eizo Sugawa, who also made the excellent Tatsuya Nakadai vehicle The Beast Must Die (1959). An impressive array of talent is on display in other departments, too – the music score is by Japan’s foremost film composer, Toru Takemitsu, while the cast is littered with excellent actors, many of whom will be familiar from the films of Akira Kurosawa.

Ryo Ikebe

Ryo IkebeGiving a flawless performance in a role which was probably the highlight of her career, Junko Ikeuchi stars as Tamiko, a young woman working as a maid to support her older, bedridden husband, Kanji (Satoshi Morizuka), a man with bad teeth and a foot fetish who, despite his condition, is carrying on with another woman. When Tamiko comes home one day and catches him in the act, the other woman flees and a disgusted Tamiko has to fight off the advances of the frustrated Kanji.

Yunosuke Ito and Junko Ikeuchi

Yunosuke Ito and Junko Ikeuchi

At the inn where she works, Tamiko has attracted the attention of a wealthy customer, Kotaki (a typically wooden Ryo Ikebe). She becomes his favourite and he offers her the chance of a better life, putting a dangerous idea into her head – in order to take full advantage of her new opportunity, she decides to get rid of her troublesome husband permanently. Kotaki introduces her to Hadano (Yunosuke Ito), a dodgy lawyer who finds her a new position looking after the rich and powerful Kito (Eitaro Ozawa), who keeps a gruesome statute of the fearsome Buddhist deity Fudo Myo-o in his bedroom. In a cruel twist of ironic fate, it turns out that Kito is another randy, bedridden monster with bad teeth, and she is forced to become his mistress while continuing her relationship with Kotaki.

Eitaro Ozawa

Eitaro Ozawa

Meanwhile, the death of Kanji is being investigated by a police detective, Hisatsune (Keiju Kobayashi). Becoming convinced that Tamiko murdered her husband, he tries to use the information to pressure her into having sex with him. Hisatsune has also uncovered some information about the murky pasts of Kito and Hadano; as a result, strings are pulled behind the scenes and he is fired from the police force. His attempt to get revenge by giving the story to a newspaper backfires, and soon nobody involved is safe…

Keiju Kobayashi

Keiju KobayashiThe shocking denouement of Beast Alley features a further cruel irony for Tamiko and provides an appropriate ending to a misanthropic movie in which everyone turns out to be a scumbag. Takemitsu’s music is typically subtle and there is fine high-contrast black and white ‘scope photography throughout by Yasumichi Fukuzawa (who has oddly few credits but also worked for Kurosawa and Mikio Naruse). Also notable among the cast are Kurosawa favourite Noriko Sengoku as a scene-stealing maid and Tatsuya Nakadai’s mentor, Koreya Senda, in a tiny but significant non-speaking part.

Noriko Sengoku

Noriko SengokuHowever, the film’s most impressive asset is the remarkable lead performance by Junko Ikeuchi, who has to play just about every emotion in the book and is never less than entirely convincing. In 1966, she travelled to Argentina, where the picture had been nominated for Best Film at the Mar del Plata Film Festival. Unfortunately, it lost out to Czechoslovakia’s entry, Long Live the Republic! Although she never enjoyed such a good role again in the cinema, Ikeuchi went on to become one of the most successful actresses in Japanese television drama. A heavy smoker, she died of lung cancer in 2010 at the age of 76.

Watched without subtitles.

Fudo Myo-o

Fudo Myo-oNovember 14, 2022

Honno-ji in Flames / 敵は本能寺にあり / Teki wa Honnoji ni ari (‘The Enemy is at Honno-ji’, 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #42

The presence of Chikage Awashima and Keiko Kishi among the cast of this jidaigeki (period drama) made me think it might be a cut above the average, and so it is – at least to some extent…

The late 16th-century: Akechi Mitsuhide (Hakuo Matsumoto) is a daimyoand military commander continually bullied into doing things he doesn’t want to by his lord, Oda Nobunaga (Takahiro Tamura). He’s been forced to break his word to two brothers fighting on the opposing side that he would spare their lives if they surrendered, he’s been manipulated into agreeing to a marriage for his daughter, Tama (Keiko Kishi), against her wishes, and there seems to be no respite. Notions of feudal fealty dictate that Mitsuhide go along with all this without complaint – it’s a classic example of the conflict in Japanese drama between giri (obligation) and ninjo (inclination). One day, Mitsuhide raises his voice in objection to a command from his lord and Nobunaga beats him over the head in front of his peers, leaving a permanent scar. This proves to be one humiliation too far for Mitsuhide, and the worm finally turns…

The basic premise is not dissimilar to that of the later Samurai Rebellion (1967), although kabuki actor Hakuo Matsumoto (1910-82) does not quite have the charisma of Toshiro Mifune (who does?) and receives few opportunities to show what he can do with a sword as this is no chanbara. However, the few short battle scenes are well-staged and Matsumoto certainly looks the part. As an actor, he was apparently keen to push the boundaries and even played Othello on stage the same year.

Honno-ji in Flames is quite a lavish Shochiku production directed by veteran Tatsuo Osone (1904-63), who also made the previously-reviewed contemporary crime thriller, Kao, but was more in his element here. This is a well-made film with good camerawork courtesy of Osone’s frequent collaborator Hideo Ishimoto and a decent if unremarkable score by Mitsuo Kato. The screenplay is an original work co-written by the historical novelist Shotaro Ikenami (1923-1990), author of the books on which the Hideo Gosha films Kumokiri Nizaemon (1978) and Hunter in the Dark (1979) were based. In this case, he used the true story of Akechi Mitsuhide and filled in the gaps (Mitsuhide did indeed rebel against his lord, Oda Nobunaga, at Honno-ji temple in Kyoto in 1582).

Michiko Saga and Takahiro Tamura

Michiko Saga and Takahiro Tamura

What the film lacks is characters of more than one dimension – a shame, as a bit more depth in this department might have made it a classic. It does, however, have a downbeat ending I found highly effective and some nice touches, such as the scene in which Nobunaga’s wife (Michiko Saga from The Mad Fox) actively participates in a battle by supplying arrows to her husband instead of running away to hide as the women so often do in these films. Overall, it’s an impressive effort well worth a look for fans of this genre.

Confusingly, Hakuo Matsumoto was also known as Koshiro Matsumoto VIII, and the filmography for ‘Koshiro Matsumoto’ on IMDb contains entries not only for him, but for his son, Koshiro Matsumoto IX (1942-) and grandson, Koshiro Matsumoto X (1973-), while there’s also a separate page for ‘Hakuo Matsumoto.’

November 3, 2022

Patience Has an End / ごろつき無宿 / Gorotsuki mushuku (‘Rogue Wanderer’) 1971

Obscure Japanese Film #41

Ken Takakura and Takashi Shimura

Ken Takakura and Takashi Shimura

Isamu (Ken Takakura) works in a coal mine in Kyushi with his father (Yoshi Kato), who is fatally injured in a cave-in. On his deathbed, his dad’s last wish is that Isamu quit the mines to escape suffering a similar fate. Soon after, Isamu heads for Tokyo. On the train, he meets Yuki (Etsuko Nami), who is also on her way to begin a new life as a professional volleyball player in the big city (where they will keep running into each other). Once in Tokyo, Isamu finds work at Toei Chemicals, where his first job is to help expand their territory and build a fence which cuts off an important access route for the local fishermen, one of whom is killed as a result. Isamu soon realises he is basically a hired stooge for a company run by ruthless yakuza, so he quits. However, he has impressed Asakawa (Takashi Shimura), an ex-yakuza gone straight who now runs a street-vending business. Asakawa hires Isamu as a candy floss salesman (!), but he becomes involved in an ongoing conflict between Asakawa’s people and the same yakuza gang associated with Toei Chemicals. Meanwhile, Isamu pursues his dream of graduating from selling candy floss to running a banana stall, as that’s where the real money lies.,,

What I like about this Toei production is that, while not quite an out-and-out comedy, it has a real sense of its own absurdity and provides quite a few laughs along the way. For example, there’s a scene in which Takakura pokes fun at his own famously unsmiling screen persona; his vain efforts to practise smiling in the hope it will help increase his sales are hilarious. He also spends a great deal of time struggling to learn a sales pitch filled with innuendos about bananas. Toshiaki Minami and Haruo Tanaka are amusing too as fellow vendors – the latter’s face when forcing himself to eat Isamu’s mother’s inedible home-made mochi being especially priceless.

Takakura trying to smile

Takakura trying to smile

Yoko Hayama and Haruo Tanaka

Yoko Hayama and Haruo Tanaka

Toshiaki Minami far right

Toshiaki Minami far rightAfter the mainly comic middle section, the film turns into a straight yakuza film for the well-staged and bloody climax in which Isamu finally loses his patience and goes after the bad guys with a samurai sword. The main villains are played by yakuza movie regulars Fumio Watanabe and Akira Shioji rounding out a strong cast. While Kurosawa favourite Takashi Shimura’s role is nothing special, it’s always great to see this actor and he even gets to kick some butt himself at one point.

Fumio Watanabe and Akira Shioji

Fumio Watanabe and Akira Shioji

Patience Has an End is not a film to be taken very seriously, but it’s fast-moving and entertaining all the way, with a strong music score courtesy of Takeo Watanabe, who seems under the influence of Ennio Morricone’s spaghetti westerns in his use of trumpets. Director Yasuo Furuhata (1934-2019) is not well-known abroad, but he enjoyed a long-lasting association with star Ken Takakura and enjoyed a very successful career in Japan. He originally wanted to make more serious films, but at this stage was stuck making yakuza fare for Toei. In later years, he had the opportunity to break away from the genre and scored a big hit with Railroad Man(also starring Takakura), for which he won a number of awards.

October 27, 2022

Mother Country / 山河あり/ Sanga ari (‘There are Mountains and Rivers’) 1962

Obscure Japanese Film #40

In 1955, Japan’s top screen actress Hideko Takamine married screenwriter Zenzo Matsuyama in a match arranged by director Keisuke Kinoshita, for whom both had worked – Matsuyama had been assistant director on Kinoshita’s two Carmenfilms and written The Tattered Wings(in all of which his future wife starred), while Takamine had also played the lead in Kinoshita’s Twenty-Four Eyes. By the time of Mother Tongue, she had made a further four films for Kinoshita and was said to be his favourite actress. This 1962 production for Shochiku was very much a family affair, then – Matsuyama co-wrote and directed it, Takamine headed the cast and Kinoshita received a credit for ‘planning’ (a credit common in Japanese films at the time, but one seldom used in the West, where similar duties are usually covered by a ‘producer’ credit). Prior to this, Matsuyama had worked as a screenwriter for Masaki Kobayashi on a number of films including The Human Condition trilogy and made his first feature film as director the previous year with The Happiness of Us Alone, in which Takamine played a deaf-mute, a performance for which she won a number of awards. Her co-star from that film, Keiju Kobayashi, also appears here; in the West, he’s most familiar for his comic performance as the samurai who gets locked in the cupboard in Akira Kurosawa’s Sanjuro, but he was a major name in Japan.

Hideko Takamine receives another plum role courtesy of her husband in this film. She plays Kishimo, a young woman who emigrates to Hawaii with her husband, Yoshio (Takahiro Tamura), around 1918. They have been ‘chased out of Japan’ for rather vague reasons which seem to be something to do with her husband engaging in a relationship with her before she was married and while he was a teacher. On the ship, they become friends with a couple in a similar position, Kyuhei (Keiju Kobayashi) and Sumi (Yoshiko Kuga, another major star). Arriving in Hawaii, they begin work as farmers and find themselves treated little better than slaves. However, when both women fall pregnant, their husbands are motivated to work as hard as possible to lift themselves out of poverty and build a future for their children. 10 years pass. Yoshio has become a teacher and Kyuhei a shopkeeper. Their children know some Japanese but prefer to talk English. A further seven years go by – the parents are by this point fairly well-off and their now grown-up children are able to live the sort of carefree life their parents never experienced, but are disturbed by reports of Japan’s increasing aggression and begin to feel embarrassed about their background. Then the Japanese air force bomb Pearl Harbour and the families find themselves torn between two cultures, both of which now regard them as the enemy.

The only other film I know of about the plight of Japanese-Americans during World War 2 is Alan Parker’s Come See the Paradise (1990), so Matsuyama deserves credit for tackling a thorny subject more usually swept under the carpet. Working from an original screenplay co-written with Kurosawa collaborator Eijiro Hisaita, mostly shot on location in Hawaii (I think) and covering a span of 30 years or so, it’s certainly an ambitious production. Unfortunately, it has a tendency to lapse into sentimentality, a quality often underlined by Chuji Kinoshita’s alternately string-laden and Hawaiian score. Despite a few scenes which hit home, the overall result is a well-produced melodramatic weepie topped off by a superb performance from the great Takamine, who also receives a credit for ‘costume supervision’ and even gets to perform a traditional Hawaiian song in one scene. Another bonus is the presence of splendidly acerbic character actor Koji Mitsui as the forthright elder of the Japanese immigrant community.

Koji Mitsui

Koji Mitsui