M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 17

May 21, 2023

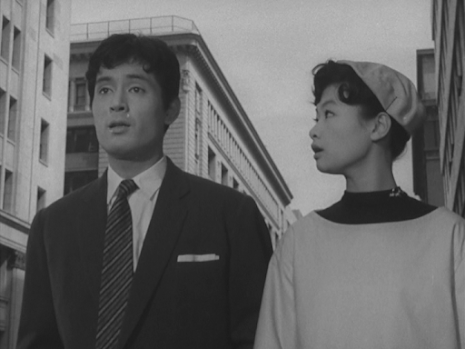

Women of Tokyo / 東京の女性 / Tokyo no josei (1939)

Obscure Japanese Film #59

Setsuko Hara

Setsuko HaraWomen of Tokyo stars Setsuko Hara as the conveniently-named Setsuko, who works as a typist for an automobile company. She has eyes for Kohata (Akira Tatematsu), a salesman for the same company, but is put off when she sees him get into a fist-fight with another salesman, Takayama (Taizo Fukami), who has accused Kohata of stealing a contract from him then begged for it back on the grounds that he needs the money for his sick wife and children. However, when Kohata explains to Setsuko that he knows for a fact that Takayama’s wife is not sick and he’s just an unscrupulous character who will say anything to get a contract, they become friends again.

Akira Tatematsu

Akira TatematsuWhen Setsuko’s father (Kinji Fujiwa) falls ill, the family need money for his hospital bills, so Setsuko asks Kohata to help her join the sales department and become the company’s first female salesperson. Kohata is reluctant to do so and warns her of the unpleasantness she is likely to face from his aggressively competitive colleagues, but she is undeterred and he relents. After a slow start, she begins to have success in her new career, but her burgeoning self-confidence makes Kohata uneasy and he becomes interested in her cute younger sister Mizuyo (Kazuko Enami) instead…

Kazuko Enami

Kazuko EnamiThis Toho production was tailor-made as a vehicle for their 19-year-old star Setsuko Hara who, despite her youth, was already something of a veteran, having made 26 films before this one. Hara is seen in a rather implausible range of attractive outfits for a character supposedly in desperate financial straits for most of the running time, but fortunately her performance is quite natural and convincing.

Based on a novel published the same year and said to have been written for Hara by the prolific Fumio Niwa (a male), this has a surprisingly strong feminist perspective for its time. Indeed, there may be even be a hint of lesbianism in Setsuko's relationship with her best friend, Takiko (Reiko Mizukami), and the rather mannish they both sometimes dress.

Reiko Minakami

Reiko MinakamiThe film also criticises the culture of unchecked capitalism in which the salespeople become little better than hungry wolves fighting over a scrap of meat, while another interesting aspect is the ending, which plays with audience expectations in quite a clever way.

I was also struck by the way director Osamu Fushimizu filmed two scenes in particular. The dialogue between Kohata and Mizuyo shot through the window of a moving car must have been difficult to achieve in 1939, and even 20 years later such scenes were usually filmed in a studio with unconvincing back projection. The other scene which stood out for me was the one in which Setsuko is assaulted in the street by the villain of the piece, Takayama – a sequence which Fushimizu makes more threatening through his use of background noise and the odd reflections on Takayama’s face.

As much of the film is less remarkable, it’s difficult to assess the extent of Fushimizu’s talent on this picture alone, but he has an intriguing Kurosawa connection, having employed Kurosawa as an assistant director on his 1936 film Tokyo Rhapsody and later made Current of Youth (1942) from a Kurosawa script. Fushimizu made 15 films before his death at the premature age of 31 in 1942 (the cause is not known to me, but I would be interested to hear it if anyone knows). Another ill-fated contributor to this film was actress Kazuko Enami, who succumbed to tuberculosis in 1947 and was the mother of Kyoko ‘Woman Gambler’ Enami. Women of Tokyo was remade in 1960 by Shigeo Tanaka with Fujiko Yamamoto starring.

Thanks to Japana Kino for making Women of Tokyo available with English subtitles on YouTube here.

May 13, 2023

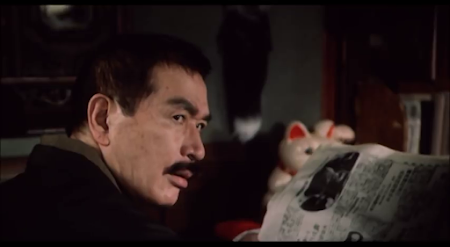

Wild Detective / Outlaw Cop / やさぐれ刑事 / Yasagure keiji (1976)

Obscure Japanese Film #58

Based on a 1975 novel of the same name by Giichi Fujimoto (1933-2012), this Shochiku production stars an impressively-sideburned Yoshio Harada as Nishino, a police detective based in Hokkaido’s capital, Sapporo. When he learns that members of an Osaka-based yakuza gang, the Jumonji-gumi, are flying in to organise a drug-trafficking network with the local mob, he goes to the airport to check them out and discovers that their leader is none other than Sugitani (Etsushi Takahashi), a criminal he had arrested and sent to prison seven years earlier. Naturally, there’s no love lost between these two and Nishino also wants to prevent the gang establishing themselves on his turf, so he and his colleagues begin harassing them at every opportunity. Sugitani decides he’s not going to take this lying down, so he poses as a car salesman and seduces Nishino’s wife, Maho (Naoko Otani). This proves to be easy as Nishino is so wrapped up in his job that he pays her little attention. Sugitani even talks her into running away with him and, by the time she learns his true identity and motivation, they’re already on a boat speeding away from Hokkaido to Honshu and there’s no going back. When Nishino learns about this, he’s so incensed that he decks a colleague, quits the force and goes after Sugitano, tracking him first to Aomori, where he discovers that Maho has been forced into prostitution. Maho becomes her husband’s spy, feeding him information about Sugitano’s movements, but Nishino will have to pursue his enemy to the other end of the country before he finally catches up with him.

Yusuke Watanabe was a prolific director and screenwriter who directed 64 films and numerous television dramas between 1957 and his death in 1985 at the age of 58. He led a rather schizophrenic career, pioneering Toei’s early ventures into eroticism as a means to compete with TV with films like Two Bitches (1964), later making a series of movie vehicles for pop band The Drifters as well as comedies, dramas and seemingly just about everything else, including episodes of Monkey (1978-80). Wild Detective appears to be the only one of his films to be accessible outside Japan, at least with subtitles, but he has done a good job here on the whole and keeps things moving at a relentlessly fast pace. The film is also well-shot, mostly on location, by Keiji Maruyama, and features an effective music score by Hajime Kaburagi.

Watanabe’s film has one of the longest pre-credits sequences I’ve ever seen – it’s not until 18 minutes in, after Nishino quits the force, that the main title suddenly pops up on the screen. Wild Detective also features one of the most unsympathetic ‘heroes’ I can recall in a film – Nishino treats his nice wife like a doormat and, although the fact that she leaves him is entirely his own fault, the first thing he does when they are reunited is to slap her around. In fact, there’s really nothing he does in the whole film which elicits any sympathy, so if you’re looking for a film with someone to root for, look elsewhere!

Although Ken Takakura is listed among the cast credits on IMDb, he’s not in it. However, it was nice to see Hideji Otaki appear briefly as a shadowy Mr Big, as he also did for director Kei Kumai in both A Chain of Islands (1965) and Wilful Murder (1981).

May 10, 2023

Darkness at Noon /真昼の暗黒 / Mahiru no ankoku

Obscure Japanese Film #57

Perhaps the first thing to note about this independent production is that it has nothing whatever to do with the famous Arthur Koestler novel of the same name, although it does have certain themes in common – namely, incarceration and interrogation. However, the techniques employed by the interrogators in this film are considerably less subtle than the more psychological methods detailed in Koestler’s book.

In a brief pre-credits sequence, we see the bodies of an elderly couple being discovered by the police. The man has been killed with an axe, while the woman is found hanging in the doorway, but this is no whodunit – once the credits roll, the cops waste no time tracking down the murderer and soon arrest Kojima (Teruo Matsuyama), a juvenile delinquent. He cracks easily and confesses that he had sneaked into the couple’s house to steal money to pay off his debts. When the old man woke up, he panicked and killed him, then decided to murder the wife as well, hoping that the police would think she had done her husband in, then committed suicide in a fit of remorse. Unfortunately, the police don’t believe the crime could be the work of one person, so they put pressure on Kojima to name his accomplices, telling him that he’s sure to get the death penalty if he insists he acted alone. Kojima tells them what they want to hear, saying there were four others involved and the whole thing was masterminded by Uemura (Kojiro Kusanagi). The police arrest Uemura, dragging him away from his fiancee (Sachiko Hidari), and proceed to beat the living crap out of him in the hope of extracting a confession…

Shinobu Hashimoto’s screenplay is based on a best-selling non-fiction book by former lawyer Masaki Hiroshi (1896-1975) which told the story of a case known as the Hakkai Incident (although Hashimoto apparently made little use of the book and conducted his own research). The original crime took place in 1951, and the events which followed were widely reported in the press and stirred up a great deal of public interest. As the film was released while the first Supreme Court appeal was pending, Hashimoto had to change the names of the accused men, but otherwise appears to have stuck to the facts as far as possible. Like Satsuo Yamamoto, director Tadashi Imai was a left-wing filmmaker who specialised in making pictures dealing with social issues – in this case how a miscarriage of justice is brought about as a direct result of police brutality. This theme seems rather old hat now, but it was one of the first Japanese films to tackle such a subject and was viewed as an important picture at the time, scoring a hit at the box office and winning a number of awards.

It’s debatable how much of an influence the film had on the fates of those wrongly convicted as the real case was to drag on for many more years. After a series of U-turns, a third Supreme Court appeal finally decided that ‘Kojima’ had acted alone, and acquitted the others, most of whom had already spent many years in prison by then. ‘Kojima’ himself was released on parole in 1971 after having served 20 years, but was arrested 5 years later on suspicion of a new murder. He died of natural causes while the trial was in progress.

Darkness at Noon has no real ‘stars’ as such – the producers probably felt that the publicity already generated by the case would be enough to put bums on seats, and proved to be right, while Imai deliberately cast an unknown, Teruo Matsuyama, in the central role of Kojima. Matsuyama's film career never really took off, but he went on to enjoy a long career on stage and television, popping up in the occasional movie along the way. The best-known cast member is probably Sachiko ‘Insect Woman’ Hidari; it has been said that this was the role which led to her being taken seriously as a dramatic actor. However, in this case she’s really just part of an ensemble which includes such familiar faces as Tanie Kitabayashi, Taiji Tonoyama and So Yamamura.

On the whole, it’s a fairly interesting, well-made film, but one that’s not quite distinguished enough in its treatment to hold up as a forgotten classic. The choral singing on the soundtrack at the end in particular has not dated well and the relevance of the picture has inevitably faded.

May 4, 2023

The Song Lantern / 歌行燈 / Uta andon (1943)

Obscure Japanese Film #56

This film adaptation of a Japanese literary classic tells the story of Kitahachi (Shotaro Hanayagi), the son of a famous Noh actor, Genzaburo Onchi (Ichijiro Oya). Kitahachi is angered by stories of 'So-zan' (Masao Murata), a provincial amateur who has been bragging that he can perform Noh songs better than 'those guys in Tokyo.' He decides to pay a visit to So-zan to find out how good he really is. So-zan is a blind masseur turned restaurant owner said to be keeping three concubines, the thought of which Kitahachi finds distasteful and only angers him further. Unimpressed by So-zan's singing, he takes him down a peg or two, humiliating the braggart by beating out the correct rhythm to the song, causing So-zan to falter in his performance and lose face. Kitahachi follows this victory by openly insulting him, then walks out. So-zan sends O-Sode (Isuzu Yamada) – the young woman who had ushered him in to see So-zan and whom Kitahachi takes to be one of the concubines – to go after Kitahachi and bring him back, but he rebuffs her. The following day, he learns that So-zan has committed suicide. When Kitahachi's father hears what has transpired, he is furious and disowns Kitahachi, who is soon reduced to becoming a wandering samisen player. One day, he encounters O-Sode, whom he has by this time learned was actually So-zan's daughter. (This is significant as he would never have been so harsh towards her father had he known this at the time.) She is now working as a geisha but is in danger of losing her job as she's unable to play the shamisen despite having made a great effort to learn the instrument. Stricken by guilt, Kitahachi sees a way of making amends and decides to help her. As she clearly has no talent for the shamisen, he teaches her a Noh dance instead…

The Song Lantern was based on a 1910 novella by Kyoka Izumi (1873-1939). Izumi was held in high esteem by a number of more famous Japanese writers, including Yukio Mishima, Junichiro Tanizaki and Yasunari Kawabata, while his work has formed the basis of films by directors such as Kenji Mizoguchi, Masahiro Shinoda and Kon Ichikawa. The original, which has been published in English as ‘A Song by Lantern Light’, is regarded as one of its author’s masterworks. Unravelling in a clever flashback structure which flits between the past and present in a way that is ahead of its time, and containing some nice humour mixed in with the tragedy, it stands up very well indeed. This film version uses a more conventional narrative structure but otherwise remains remarkably faithful for the most part, although the ending is less enigmatic and more upbeat. Another difference is that So-zan reappears as a ghost in the film – though, like the ghost of Banquo in Macbeth, it’s left ambiguous as to whether this is a ‘real’ ghost or, a hallucination brought on by a guilty conscience. Many of Izumi’s stories do feature ghosts, but not ‘A Song by Lantern Light’.

The screenplay was written by Mantaro Kubota (1889-1963), a writer of novels, plays and haiku with four screenplay credits, three of which are for adaptations of Izumi stories. His screenplay for The Song Lantern was apparently finished in 1940, but when production of the film was delayed, it was instead staged at Tokyo’s Meijiza theatre in July of that year with Shotaro Hanayagi (star of the film version) in the lead. Hanayagi (1894-1965), who somewhat resembles Kazuo Hasegawa, was a kabuki actor specialising in female roles who had starred in a stage version of Izumi’s novel Nihonbashi (Bridge of Japan) back in 1915. He only made a handful of films, most notable of which was his leading role for Kenji Mizoguchi in The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), but he went on to be awarded the title of ‘Living National Treasure’.

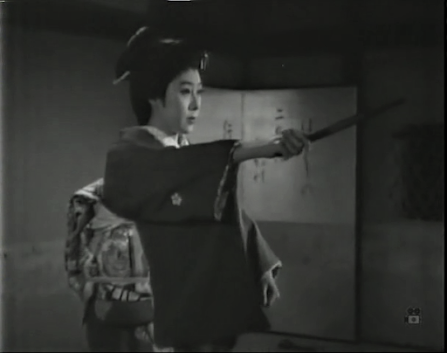

Isuzu Yamada

Isuzu Yamada

Another cast member with an affinity for the work of Kyoka Izumi is Isuzu Yamada, a striking, skilful and versatile actress who will always be remembered for her ‘Lady Macbeth’ in Throne of Blood, but deserves to be remembered for lot more. She had also starred in Mizoguchi’s The Downfall of Osen (1934), and Masahiro Makino’s two-part Onna Keizu (1942), all of which were based on Izumi stories.

13 years into his directorial career at this point, Mikio Naruse was not yet considered one of the grand masters of Japanese cinema, but certainly had an excellent reputation as a maker of intelligent, sensitive, literary dramas. As this film was made during the war years, Naruse would have been working with limited resources and interference from the authorities, so it is to his credit that he managed to avoid making military propaganda and was able to produce such a high quality film under these circumstances. In my opinion, this is one Naruse film which deserves a little more love. Although some lengthy scenes of Noh performance may stretch the patience of some viewers, it has a strong story which draws you in, fine performances and some notably well-shot sequences, such as the ones in which Kitahachi teaches O-Mie the Noh dance in the forest. As far as I can tell, the film is only available in a rather faded VHS transfer – a pity, as it’s certainly worthy of restoration.

The Song Lantern was remade in 1960 by Teinosuke Kinugasa (working from a new script), who cast Raizo Ichikawa and Fujiko Yamamoto in the leads.

The original story can be found in In Light of Shadows: More Gothic Tales by Izumi Kyoka translated by Charles Shiro Inouye (University of Hawaii Press, 2005)

April 25, 2023

The Hole / 穴 / Ana (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #55

Intheir first film together, a comedy thriller made for the Daiei company, directorKon Ichikawa gives star Machiko Kyo one of her best roles as a resourcefulheroine who outsmarts all the scheming men surrounding her. She plays Nagako, areporter who is fired from her job after writing an article exposing policecorruption.

Her flatmate, Suga (old lady specialist Tanie Kitabayashi lookingyoung for a change), inspired by stories of people mysteriously going missingin Japan, suggests an idea she can pitch to a magazine: Nagako will ‘go missing’herself for a month while the magazine offers a 500,000 yen reward to anyreader who can find her.

However, when the magazine editor refuses to give heran advance, Nagako approaches dodgy bank manager Shirasu (So Yamamura) for aloan to cover her expenses, but he conspires with a senior clerk, Chigi (EijiFunakoshi), to win the prize money for himself, after which things becomeincreasingly complicated to the point of (clearly intentional) absurdity.

MachikoKyo, appearing in a number of guises and showing a real flair for comedy here,is in almost every scene and provides reason enough for watching.

Feminists willenjoy watching her run rings around the men, and one also has to admire herwillingness to look entirely unglamorous in a number of scenes. Although it’sKyo who carries the film, The Hole isalso a fast-paced and fun movie with a strong supporting cast packed withIchikawa regulars, including the wonderful Jun Hamamura as an eccentric cabdriver.

The director even throws in a self-mocking cameo from Shintaro Ishihara,who says at one point, ‘I found novel writing boring. I sing now.’ (Ishihara,who began as a writer, was known for dabbling in acting and various otherpursuits; he later became a right-wing politician and was Governer of Tokyofrom 1999-2012).

Thescreenplay was written by Ichikawa and his wife Natto Wada under theirpseudonym ‘Kurisutei’, a nod to Agatha Christie. However, they failed to creditWilliam Pearson, the American author upon whose 1954 novel The Beautiful Frame the central idea was lifted. Having said that,it should be noted that the novel featured a male protagonist and seems to havebeen a fairly straight piece of pulp fiction which Ichikawa and Wada turnedinto something far more original.

April 18, 2023

Mikkokusha /密告者 (‘The Informer’) 1965

Obscure Japanese Film #54

This Daiei thriller stars Jiro Tamiya as Segawa, a bankrupt stockbroker now reduced to working as a salesman. He has a huge debt to pay off, but unfortunately he’s been unable to sell a single one of the ‘electric massagers’ he’s supposed to be flogging, so he decides to ask his boss, Sawai (Yusuke Takita), if he can try selling something else instead. Sawai confesses that the massagers are just a front for an industrial espionage agency he’s running, then offers Segawa some well-paid work spying on a pharmaceutical company run by Ogino (Akira Natsuki), also confessing that this was the real reason he had recruited Segawa in the first place and that he has been waiting for the right moment to tell him. Sawai knows that Segawa used to be engaged to Ogino’s wife, Eiko (Kaoru Izumi), and hopes that this connection will give Segawa a valuable ‘in’ through which he can begin gathering information. Segawa finds the task easier than expected and soon begins getting results, but it all goes wrong when he finds himself the prime suspect in a murder case. However, Eiko’s sister, Toshiko (Shiho Fujimura) seems convinced of his innocence and willing to do anything she can to help him…

Mikkokusha sees Jiro Tamiya in a typical role as an ambitious womaniser who’s not too big in the morals department – see also Black Test Car, Stolen Pleasure and, most notably, The Great White Tower (among others). Tamiya excelled at playing such characters, and was also an athletic type and proficient in karate – a useful skill when called upon to perform in action scenes, of which this film has a number of good ones in the second half. Unfortunately, his film career would soon go off the rails. In 1968, he complained to the bosses at Daiei studios about having been relegated to fourth billing on the posters for Tadashi Imai’s Fushin no toki (1968) below Ayako Wakao, Mariko Kaga and Mariko Okada despite having the lead role. Daiei changed the billing but fired him. Due to an arrangement between the five big film companies in Japan, this meant that none of the other studios would sign him and he had to make do with TV work and roles in occasional independent films (something similar had happened to Fujiko Yamamoto in 1963). In the following years, Tamiya embarked on a number of unsuccessful business ventures and suffered from health issues culminating in depression and a mental breakdown. He committed suicide with a hunting rifle in 1978 aged just 43.

Director Shigeo Tanaka (1907-1992) is generally regarded as a journeyman, but it’s an indication of the quality of Japanese cinema during this period that even the so-called hacks were, at the least, highly competent. Tanaka enjoyed a long career, making his first film in 1931, and his last in 1980. He’s probably best remembered for the ‘Woman Gambler’ series starring Kyoko Enami (who apparently replaced Ayako Wakao when the latter had to pull out for health reasons). Enami also appears here as Segawa’s girlfriend, but the plum female role goes to Shiho Fujimura, who is especially effective in her final scene. Yusuke Takita is also memorable as the suave and slippery Sawai.

The industrial espionage thriller became a subgenre of its own in 1960s Japanese cinema, although Mikkokusha focuses mainly on the murder mystery aspect of the plot. This is quite convoluted but pretty clever, and overall the film has a lot going for it, including some fine black-and-white ‘scope photography by Fujio Morita, who went on to shoot many of Hideo Gosha’s films.

The screenplay by Hajime Takaiwa was based on a just-published novel of the same name by Akimitsu Takagi later published in English translation by Soho Press in 2001 as The Informer.

Thanks to Coralsundy for the English subtitles, which can be found here.

April 10, 2023

All My Children / みんなわが子 / Minna waga ko (1963)

Obscure Japanese Film #53

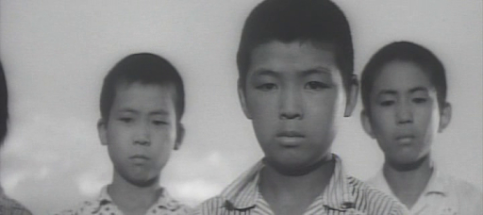

Director Miyoji Ieki(1911-76) made something of a speciality out of films focusing on children; thisfilm, along with Stepbrothers (1957)and The Wayside Pebble (1964),certainly suggests that he had a genuine affinity for the subject and isanother sensitive portrayal of the trials and tribulations experienced by thosein their formative years. In this case, the children are evacuees sufferingfrom homesickness and hunger in the final days of the war.

Like fellow directorSatsuo Yamamoto, Ieki was fired by a major studio in the late 1940s due to hisleft-wing sympathies and subsequently forced to rely on a combination ofindependent production and freelancing in order to continue his career. All My Children is an example of theformer, which may be one reason for the lack of big names among the cast.However, Hitomi Nakahara (b.1936) was a star who had been under contract toToei since her debut in 1954 and was here appearing in one of her final filmroles for many years before switching to TV in 1964. As the children’s teacher,she has a doe-eyed, Audrey Hepburn-like quality that’s quite appealing. She’sthe closest thing to a main character in the film – really it’s an ensemblepiece with no plot to speak of. Instead, we have an episodic narrative whichencompasses everything from a double suicide to a desperate second evacuationto a mountain village, but it holds the interest throughout thanks to Ieki’s excellentstaging and attention to detail.

I suspect that thisfilm provides a pretty accurate portrayal of what it must have been like forsuch children and their teachers at the time, especially as the screenplay by former Kurosawa collaborator Keinosuke Uekasa (One Wonderful Sunday, Drunken Angel) was ‘based on theGekkohara Elementary School volume of ARecord of School Children Evacuations’.Indeed, several moments called tomind Tatsuya Nakadai’s description of his wartime childhood, such as the factthat the children were so hungry that they resorted to eating toothpaste while,early on in the film, we see them being trained how to kill American soldierswith bamboo spears. All My Childrenprovides a sobering spectacle in showing us the extent to which the right-wingmilitary had gained control of the country and been largely successful in brainwashingthe citizens, costing countless innocent lives and almost destroying thecountry in the process. The film avoids cheap sentimentality for the most partand, just when it threatens to end on a maudlin note, Ieki deftly subverts our expectationswith a final scene in which the resilience of the children provides a lessonfor their teachers.

Finally, the music: Sei Ikeno’sharpsichord soundtrack may be an odd choice, but it works better than you mightexpect.

April 1, 2023

The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty /憲兵とバラバラ死美人 / Kenpei to barabara shibijin (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #52

Set in Manchuria in 1937, The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty opens with a Japanese soldier (whose face is concealed) having a secret liaison with a young Japanese woman (Akiko Mie). We then jump to a scene in which the (thankfully unseen) rotting torso of a pregnant woman is discovered in a well at a Japanese military barracks. The corpse has contaminated the army’s water; some rookies are forced to eat rice cooked in it by their seniors, but the latter also soon find themselves forced to eat the dodgy gohan, in their case by an indignant officer – karma in action!

Just another day at the office for the Japanese Military Police

Just another day at the office for the Japanese Military Police

A military policeman, Tokusuke Kosaka (Shoji Nakayama), is sent from Tokyo to investigate the murder, but he meets with opposition from the local MPs. Despite having no evidence, they decide to pin the crime on the cook, Sergeant Tsuneyoshi (Shigeru Amachi), so they hang him upside down and try to whip a confession out of him. However, Kosaka begins to have visions of the dead woman which lead him to important clues and, eventually, the real murderer.

I have a feeling I’ve just made this film sound more interesting than it actually it is – the story has potential, but the execution here is strictly routine and the cast unremarkable. The screenplay by Akira Sugimoto was based on a 1957 book by Keisuke Kosaka (1900-1972) entitled The Military Police Squirm: 68 Days of Headless Torso Investigation (Notautsu kenpei: Kubi nashi dōtai sōsa 68-nichi), which appears to have been based on a true story. Kosaka, who had himself served as a military policeman in Manchuria and was the model for the character Kosaka in the film, has a pretty interesting bio – according to Japanese Wikipedia, he helped to save the life of the Prime Minister during the attempted military coup of 26 February 1936 and later received a death sentence as a war criminal due to his involvement in the execution of an American airman. However, he ultimately got away with serving a few years in prison before turning to writing after his release. One wonders how much we should trust such a person’s version of events – certainly, the film portrays Kosaka as the good guy and most of the other Japanese soldiers as brutes.

More of a murder mystery than a horror film despite its title, The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty, is a modest B-movie unlikely to get pulses racing these days. However, it was enough of a hit at the time that the same studio (Shintoho) produced The Military Policeman and the Ghost (Kenpei to yurei) from an original screenplay the following year, again starring Shoji Nakayama in a similar role. For his part, director Kyotaro Namiki does a competent if uninspired job – his earlier Hirate Miki (1951) was a more impressive piece of work.

Watched without subtitles.

March 26, 2023

All About Marriage / 結婚のすべて / Kekkon no subete (1958)

Obscure Japanese Film #51

Michiyo Aratama and Izumi Yukimura

Michiyo Aratama and Izumi YukimuraKihachi Okamoto’s directorial debut is a light comedy which begins with a shot of a young couple kissing in a boat on a beach before the camera pulls back to reveal it’s merely a scene being shot for a movie. For the next few minutes, the film continues in faux-documentary style with some narration by an uncredited Keiju Kobayashi before settling down to focus on the main story. It’s a tale of two contrasting sisters – Yasuko (Izumi Yukimura), a very modern young woman who has fully embraced the new Westernised culture of post-war Japan, and Keiko (Michiyo Aratama), her older sister, who is always seen in Japanese dress and represents more traditional and conservative values. However, Michiyo is married to Saburo (Ken Uehara), a staid university professor who takes her somewhat for granted, as a result of which she indulges in a flirtation with Koga (Tatsuya Mihashi), the editor of a woman’s magazine. Meanwhile, Yasuko falls for a student, Hiroshi (Shinji Yamada), before discovering that he’s two-timing her with carefree young hedonist Mariko (Reiko Dan). Disillusioned, she finally takes up instead with Akira (Tatsuya Nakadai), a young man who works for her father’s company and of whom her father approves as a potential future husband.

Although handed such routine material for his first assignment as director, Okamoto invests it with considerable wit and invention along the way and certainly puts his unique stamp upon it, filling out the supporting cast with a variety of eccentric characters, several of whom verge on caricature. At times, he seems to intend a satire of a consumerist society in thrall to America and embracing everything from chewing gum to bad Elvis pastiches. In any case, his film is not only an enjoyable entertainment, but an interesting cultural artefact and I’d love to see it again with subtitles (there’s a lot of dialogue).

Toshiro Mifune

Toshiro Mifune

Tatsuya Nakadai and Izumi Yukimura

Tatsuya Nakadai and Izumi Yukimura Reiko Dan

Reiko Dan Watched without subtitles. You may also enjoy reading Robin Gatto’s review.

March 17, 2023

Under the Northern Lights / Pod severnym siyaniyem / オーロラの下で (1990)

Obscure Japanese Film #50

Koji Yakusho

Koji Yakusho

This Japanese-Russian co-production stands very much in the shadow of Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala (1975), the Russian film which had rescued the great director from a 5-year dry spell and returned him to international success with an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Like Dersu Uzala, Under the Northern Lights is another wilderness adventure set in the early years of the 20th-century.

Junko Sakurada

Junko SakuradaThe leading role is played perfectly by Koji Yakusho, a student of Tatsuya Nakadai’s who would go on to international success himself a few years later as the star of Shall We Dance?(1996) and The Eel (1997). Here, he is Genzo, a hunter and fur trapper who slips across to eastern Siberia in the hope of collecting enough hides to buy back his fiancée (Junko Sakurada) from the geisha house into which she has been sold by her poverty-stricken family. When some locals rob him, he is helped by a Russian, Arseniy (Andrei Boltnev), with whom he forms an unlikely friendship. Arseniy lives with his widowed sister Anna (Marina Zudina) and her child, and Genzo develops a bond with them too. However, the difficulties he faces mean that it takes him a long time to raise the money necessary to fulfil his dream.

Tetsuro Tanba

Tetsuro TanbaReturning to Japan after an absence of 5 years, he discovers that, believing Genzo to be dead, his former fiancée has married and had a child. In the meantime, the Russian Revolution breaks out and the Japanese government is concerned about the possibility of it spreading to Japan. Genzo, having learned to speak Russian, finds himself heading back to Siberia after being recruited as a spy by a government official (Tetsuro Tanba). On his return, he checks in on Arseniy, who turns out to be so ill that he is confined to his bed. Genzo attempts to nurse him back to health, but Arseniy dies. Genzo then has to fulfil his friend’s last wish – to deliver a vital serum to combat an epidemic in the remote rural community where Anna and her daughter are now living. In order to get there, Genzo has to travel by dog-sled and finds himself battling for survival in the harsh Siberian winter. Along the way, he receives some unlikely help in the shape of Buran, a dog which is half-wolf and which he had previously tried to kill for bounty.

If the serum part sounds familiar, it’s probably because the producers incorporated elements of a true story which occurred in Alaska in 1925 involving a Siberian Husky that later served as the basis for the animated American film Balto (1995). This part was not in the 1971 children’s book by Yukio Togawa upon which Under the Northern Lights is based, and I felt that the producers were over-egging the pudding a little by adding it.

Maksim Munzuk (Dersu Uzala) in a cameo

Maksim Munzuk (Dersu Uzala) in a cameoFor some reason, IMDb credits three directors on this film, although the film’s own credits list only Toshio Goto as director. I suspect that Sergey Vronski, a cinematographer, shot some second unit footage and Petras Abukiavicus, who co-wrote the screenplay, directed the Russian actors. In any case, Goto had experience with this challenging type of movie, having made The Old Bear Hunter (1982) and Born Wild, Run Free (1987), two films also mostly shot in remote locations and featuring wild animals. Animal welfare did not seem especially high on his agenda, though, and Under the Northern Lights features numerous scenes of animals attacking each other – it’s certainly not a film that could convincingly claim that ‘no animals were harmed in the making.’ These scenes may have prevented the film from being passed by the censor in some countries and may well be the reason why it seems to have had little or no release in the English-speaking world.

As one would expect from a Russian-Japanese co-production shot in Siberia with a half-dog, half-wolf as one of the main actors, the film had an immensely troubled and protracted shoot. While it certainly has its impressive aspects – most notably, the photography of the Siberian wilderness – the story is all over the place, and the music (full of cymbal crashes and swelling strings) strains too hard for emotion. Worth seeing, then, but certainly not on a par with Dersu Uzala.

Watched with subtitles I auto-translated from Serbian (they didn’t come out well). The Japanese dialogue had Russian narration over the top.