M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 21

May 8, 2022

Stolen Pleasure / 爛 / Tadare (1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #21

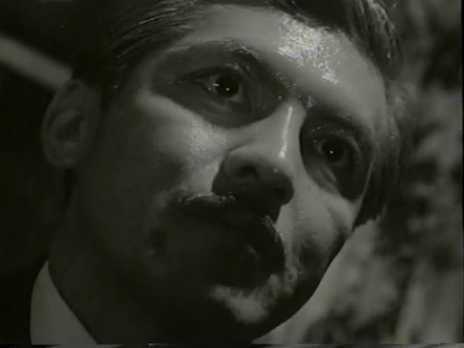

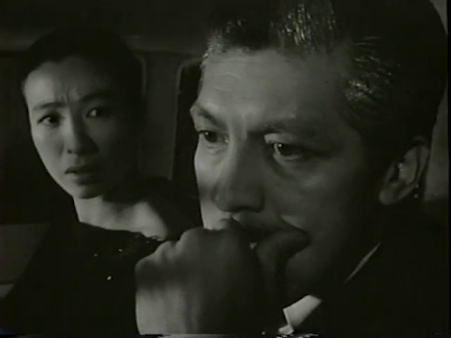

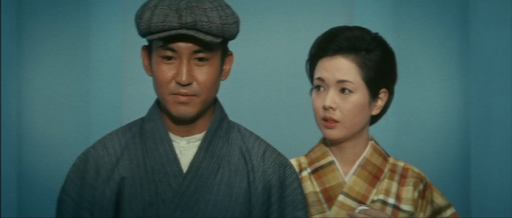

In the tenth of her 20 films for Yasuzo Masumura, Ayako Wakao plays Masuko, the 25-year-old mistress of garage owner Asai (Jiro Tamiya, best known for his portrayal of ambitious and ruthless types in films such as The Great White Tower and Black Test Car). Unbeknownst to Masuko, Asai is married to a fragile and highly-strung woman (Reiko Fujiwara). When the two women finally find out about each other, Masuko is angry but continues the affair, while Asai’s wife has a complete breakdown. Asai decides to get a divorce and move in with Masuko, but when the latter’s attractive young cousin Eiko (Yaeko Mizutani) comes to stay, it looks to be a case of what goes around comes around…

Screenwriter Kaneto Shindo adapted a 1913 novel by Shusei Tokuda (1872-1943) and gave it a contemporary setting. In Japan, Tokuda is apparently regarded as a pioneer of naturalism in literature. The only one of his novels to have been translated into English is Arakure (1915), published by the University of Hawaii Press in 2001 as Rough Living, and the basis for the Mikio Naruse film known in English as Untamed Woman (1957). The title ‘Tadare’ does not translate easily into English, but according to the blurb for a book entitled The Fiction of Tokuda Shusei by Richard Torrance, it means ‘Festering.’ As you can hardly call a movie ‘Festering’, Stolen Pleasureseems a reasonable substitute.

If looks could kill... Wakao's revenge.

If looks could kill... Wakao's revenge.

The film is a very well-made and -acted adult drama with a slightly eccentric and whimsical avant-garde jazz score I took to be the work of Toshiro Mayuzumi, but which was actually composed by Sei Ikeno, who did a number of other films for Masumura, including Red Angel. The cinematography by Masumura regular Setsuo Kobayashi (also a favourite of Kon Ichikawa) is first rate, with the widescreen frame used to full advantage and the range of compositions endlessly inventive. Masumura’s characteristically tight editing is also much in evidence, especially during a lengthy and apparently chaotic fight sequence. Indeed, almost all involved are at the top of their game here and in my opinion this is one of Masumura’s best films. Jiro Tamiya and Reiko Fujiwaraare perfect in their roles, while Wakao was so obviously an acting genius by this stage in her career that Masumura entrusts her with delivering the film’s ending through facial expression alone.

Jiro Tamiya and Reiko Fujiwara

Jiro Tamiya and Reiko Fujiwara

Despite its many fine qualities, Stolen Pleasure seems unlikely to be everyone’s cup of green tea – the characters are all unpleasant and treat each other shabbily, so there is no-one really to root for. Although it would be possible to see the film as a moralising tale about the price of infidelity, I felt it went deeper than that and was more a study of how so-called civilised people are in reality at the mercy of their primal instincts.

Reiko Fijiwara (1932-2002) was briefly married to Tomisaburo Wakayama; she retired from acting in 1966.

May 3, 2022

Policeman's Diary / 警察日記 / Keisatsu nikki (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #20

Rentaro Mikuni and Kaneko Iwasaki

Rentaro Mikuni and Kaneko Iwasaki

Rentaro Mikuni, star of my previous post’s film, appears here on the other side of the law, but in a smaller role, as this Nikkatsu production is an ensemble piece featuring a cast of well-known actors, each of whom has limited screen time. Here, Mikuni is a naïve country policeman who falls for a young woman (Kaneko Iwasaki) he rescues from the clutches of a people trafficker played by Haruko Sugimura.

Masao Mishima plays Mikuni’s boss, while Taiji Tonoyama and Hisaya Morishige appear as his colleagues. In this world, a long way from the yakuza and seedy bars of Tokyo, the cops are all good-natured types who prefer to help people rather than lock them up. The strand which receives the most attention focuses on Police Sergeant Yoshii (Morishige); lumbered with a young girl and her baby brother who have been abandoned on a train by their mother, he finds a temporary home for the baby and takes the girl into his own house as he already has five kids and figures one more will make no difference.

Taiji Tonoyama, Hisaya Morishige, Terumi Niki and Joe Shishido

Taiji Tonoyama, Hisaya Morishige, Terumi Niki and Joe Shishido

A number of familiar faces pop up in Policeman’s Diary, many of whom will be recognisable from the films of Kurosawa...

Bokuzen Hidari (centre)

Bokuzen Hidari (centre) Miki Odagiri and Yunosuke Ito (centre)

Miki Odagiri and Yunosuke Ito (centre)

Noriko Sengoku portrays a woman abandoned by her husband who resorts to shoplifting in order to feed her children. Bokuzen Hidari plays a poor farmer, while Yunosuke Ito is an equally poor cart-puller who has been dumped by his fiancé but finds he is loved by barmaid Miki Odagiri (the cheerful young colleague of Takashi Shimura in Ikiru). Eijiro Tono, the tavern-keeper in Yojimbo, here plays a primary school teacher who lost his mind when his children were killed during the war, which he believes is still in progress. The little girl taken in by Sergeant Yoshii is played by Terumi Niki, making her official film debut at the tender age of 6, although she had appeared briefly in Seven Samurai at the age of 3. She continued acting throughout her childhood, adolescence and adulthood, appearing most memorably as the traumatised young patient who repeatedly refuses the medicine offered by Toshiro Mifune in Redbeard. Another notable actor making a debut here is Joe Shishido, who appears as a young policeman but is not immediately recognisable as this was prior to his bizarre cheek-expansion surgery.

Based on an untranslated 1952 novel by Einosuke Ito and adapted by Mikio Naruse’s regular collaborator, Toshiro Ide, Policeman’s Diary is well-directed by Seiji Hisamatsu (1912-1990), a prolific filmmaker who seems to be entirely unknown in the West. He directed his first film in 1934 for Shinko Kinema, with whom he remained until the war, during which Shinko was swallowed up in a merger, becoming part of Daiei. Hisamatsu then worked at Daiei before going freelance in 1954, when he was mainly employed by Nikkatsu, Toho and Tokyo Eiga. Like many Japanese directors, he ended his career in television after film work dried up in the late ‘60s. His filmography is full of quality dramas featuring the top actors of the day, so why this is the only film accessible outside Japan of the 101 that he directed remains a mystery. Given that his 1954 picture Onna no koyomi (Women’s Calendar) was screened in competition at Cannes, he won the Japanese Art Award in 1956 and his 1961 film Chi no hate ni ikiru mono (aka The Angry Sea) was nominated for Best Film at the Mar del Plata Film Festival in Argentina, Hisamatsu was clearly no hack.

Despite all the Kurosawa regulars among the cast, Policeman’s Diary is more reminiscent of the films of Keisuke Kinoshita, partly due to its setting in a rural community. I found it to be a charming, bittersweet comic drama from a more innocent age, and it was clearly popular as Nikkatsu produced a sequel the following year.

April 22, 2022

Crossroads of Death / 死の十字路 / Shi no jujiro (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #19

Rentaro Mikuni

Rentaro Mikuni

This Nikkatsu production is based on an untranslated 1955 novel credited to the famous mystery author Edogawa Ranpo (1894-1965) and published simply as Jujiro(‘Crossroads’). However, the novel was apparently based on a draft by one Kenji Watanabe, who was also responsible for this film’s screenplay, so one wonders how much Ranpo – whose health was failing and output dwindling at the time – really had to do with it. In any case, the plot has plenty of bizarre twists to keep mystery fans happy – although it should be said that there are also some serious plausibility issues, as we shall see!

Michiyo Aratama and Mikuni

Michiyo Aratama and Mikuni

The story concerns successful businessman Shogo (Rentaro Mikuni), who has become estranged from his wife Tomoko (Hisano Yamaoka) due to her conversion to a new religion, to which she has become wholly devoted. Shogo has found solace in the arms of his secretary, Harumi (Michiyo Aratama), now his mistress. One night, when Shogo is at Harumi’s apartment, his wife suddenly bursts in brandishing a knife and attacks Harumi, who is taking a bath. Trying to protect his mistress, Shogo is horrified to discover that he has accidentally killed Tomoko in the struggle. He carries her body to the boot of his car in order to secretly dispose of it in a disused well.

While this is happening, Yukihiko (Ko Mishima) gets into a fight at a bar when he asks Ryosuke (Shiro Osaka), the drunken brother of his girlfriend Yoshie (Izumi Ashikawa), if he will consent to their marriage. During the fight, Ryosuke falls and hits his head on a washbasin. After a few minutes he seems to be alright and staggers out into the street. Yukihiko goes after him but takes a wrong turn and loses him. Meanwhile, Shogo has been involved in a traffic accident on his way to the well. While dealing with the police, he fails to notice Ryosuke crawl into the back seat of his car, perhaps mistaking it for a cab, where he expires. Shogo manages to get away from the police and continues his grim journey, only to discover he now has a random extra corpse to deal with (!). Finally arriving at his destination, he simply throws two bodies down the well instead of one and goes home.

Shiro Osaka and Mikuni

Shiro Osaka and Mikuni

A day or two later, Yoshie is standing in front of a shop window looking at a portrait of herself painted by Ryosuke when she is approached by Minami, a man who looks remarkably like her missing brother (and is also played by Shiro Osaka). He turns out to be a private detective and offers to help look for Ryosuke. However, when he uncovers the truth, he decides to blackmail Shogo. Things end badly for everyone involved.

Izumi Ashikawa and Shiro Osaka in a shot which seems to be a homage to Fritz Lang's The Woman in the Window

Izumi Ashikawa and Shiro Osaka in a shot which seems to be a homage to Fritz Lang's The Woman in the Window

This is an enjoyable film with a fine performance by Rentaro Mikuni playing 15-20 years older than he actually was (33) as the largely sympathetic Shogo, a character who becomes a criminal purely through force of circumstance. On this occasion, Mikuni never overplays the role and it’s as if we can read Shogo’s every thought and feeling expressed in the actor’s face without his ever resorting to broad gestures. Mikuni is not always so effective, but in Crossroads of Death, he’s at the top of his game. Michiyo Aratama (who played the wife of Tatsuya Nakadai’s Kaji in The Human Condition) seems a little too wholesome to be anybody’s mistress, but is otherwise fine, while Shiro Osaka is memorably oily as the blackmailing detective.

Shiro Osaka and Mikuni

Shiro Osaka and MikuniI’ve seen two other films by director Umetsugu Inoue: Black Lizard (Kurotokage, 1962), also based on a Ranpo novel, a weird and wonderful movie starring Machiko Kyo as a whip-cracking, cross-dressing super-villain, and The Third Shadow Warrior (Daisan no kagemusha), a real gem which deserves to be much better known and is a fascinating antecedent of Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha. Inoue’s direction of Crossroads of Death is not especially distinguished on the whole but the opening murder and the night-time disposal of the two bodies are very well-executed and memorable sequences.

Watched without subtitles.

Crossroads of Death can be streamed on Amazon Japan here.

April 12, 2022

Kao (Face) / 顔 (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #18

The Seicho Matsumoto short story on which this film is loosely based appeared in English in a collection entitled The Voice and Other Stories (now out of print). The protagonist is an ambitious theatre actor whose ‘nihilistic’ face attracts the attention of a top film director, but whose big break in movies may cost him his freedom – he murdered his pregnant girlfriend some years before to evade his responsibilities and knows that a witness who saw him shortly before the crime is likely to identify him if he becomes a film star. Naturally, he decides that a second murder is the answer to his problems and, equally naturally, things fail to go as planned.

Mariko Okada and Akira Yamanouchi

Mariko Okada and Akira Yamanouchi

This Shochiku production bears little resemblance to the original. Here, the protagonist is Akiko (Mariko Okada), a fashion model who has an argument on a train with a backstreet abortionist (Akira Yamanouchi) she had been to for help (and possibly had a relationship with). A struggle ensues in which he falls from the train (with the help of a well-timed shove from Akiko). When he later dies in hospital, Akiko sends some flowers anonymously, a gesture which attracts the attention of a mild-mannered local detective (Ozu favourite Chishu Ryu). Not long after the incident, Akiko gets a break at work and finds she is to be promoted as a top model, but her plans are spoilt when Ishioka (Minoru Oki), a seedy character who had seen her arguing with the abortionist on the train, begins stirring things up.

Chishu Ryu

Chishu Ryu

Eitaro Ozawa

Eitaro Ozawa Noriko Sengoku and Mariko Okada

Noriko Sengoku and Mariko Okada

Although Eitaro Ozawa pops up as a fashion bigwig who sexually harasses Akiko and Kurosawa favourite Noriko Sengoku is memorable as her down-to-earth best friend, this is Okada’s movie all the way. As Akiko, an opportunist raised in poverty, she uses her large, wonderfully expressive eyes to considerable effect and is far more sympathetic than the one-dimensional cold-blooded murderer of Matsumoto’s original.

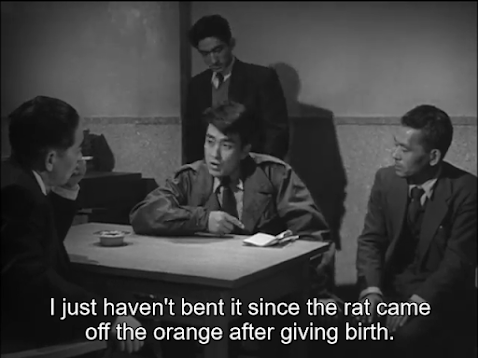

The surreal joys of auto-translate.

The surreal joys of auto-translate.

The musical saw on the soundtrack means that the music can only be the work of the prolific Toshiro Mayuzumi, an avant-garde composer of great talent whose passion for experimentation sometimes led him to make whimsical choices when scoring films. Indeed, shortly before working on Kao he had been criticised for his eccentric use of a musical saw on Kenji Mizoguchi’s Akasen chitai (puritanically retitled Street of Shame in the West). Nevertheless, he became Shohei Imamura’s composer of choice and, when John Huston was struggling to find a composer he felt could provide what he wanted for The Bible (1966), it was to Mayuzumi that he turned, re-employing him the following year for Reflections of a Golden Eye.

Director Tatsuo Osone (1904-63) seems to have been a journeyman who worked mainly on historical dramas; here, he does a competent if mostly unremarkable job, while his camera movements suggest the influence of Hollywood. In fact, there are moments that recall Hitchcock even if the film never reaches that standard.

Kao is must-see for fans of Mariko Okada and is also likely to be appreciated by those who enjoy films based on the works of crime writer Seichi Matsumoto, of which there have been many good ones, especially those directed by Yoshitaro Nomura. Matsumoto’s popularity seems never to have waned in Japan, and the original story would go on to be filmed umpteen times for television there. As far as I can tell, Kao has never been screened abroad.

The film is available on DVD (without subtitles) here.

March 30, 2022

Blackboard / ブラックボード (1986)

Obscure Japanese Film #17

Takeshi (Terutake Tsuji, centre left) and his minions dish it out.

Takeshi (Terutake Tsuji, centre left) and his minions dish it out.

One of two films by the incredibly prolific Kaneto Shindo released in 1986, Blackboardbegins with a credit sequence featuring enigmatic images of a young man in sports gear running towards the camera. A jaunty musical theme courtesy of frequent collaborator Hikaru Hayashi suggests we are about to watch a comedy. Wrong. The opening scene concerns the discovery of the body of a 15-year-old male who has obviously not died of natural causes, suggesting the film is actually going to be a murder mystery. Wrong again. The murder is soon solved – two of the boy’s classmates did it – and, as the story unfolds in flashback, we come to realise that this is actually a work of social realism examining the problem of bullying.

Takeshi's mother (Nobuko Otawa) says goodbye to her son for what turns out to be the last time.

Takeshi's mother (Nobuko Otawa) says goodbye to her son for what turns out to be the last time.

Although the tone is a little earnest and the script threatens to become didactic at times, Shindo maintains the interest well for the most part, but appears to run out of steam towards the end, ultimately offering no solutions to the all-too-common problem presented and leaving himself with nowhere to go. On the plus side, the scenes of bullying are mostly well-staged and often discomfiting to watch. However, while the headmaster of the school is portrayed as a largely decent man genuinely concerned with the wellbeing of his pupils, his apparent surprise at the existence of the problem seems a bit much after Shindo has spent so much time depicting the school as almost entirely populated by nasty little sadists.

Nobuko Otawa suffering for her art.

Nobuko Otawa suffering for her art.

Giving his long-time mistress and eventual wife Nobuko Otawa an even less glamorous role than usual, here Shindo casts her as the mother of the murdered boy; she’s a single parent who works as a cleaner, and there’s a detailed sequence of her scrubbing toilets to prove it. At least she has a couple of good dramatic scenes, unlike the great Hisashi Igawa, who has little to do except huff and puff as the Deputy Headmaster, although Shindo favourite Taiji Tonoyama is put to amusing use as a distinguished ornithologist (!) who happened to witness the murder while bird-watching.

Taiji Tonoyama demonstrates his skill with a telescope.

Taiji Tonoyama demonstrates his skill with a telescope.

Though less familiar, most of the other actors in the cast give appropriately naturalistic performances, with Terutake Tsuji making a strong film debut as Takeshi, the bully-turned-murder-victim.If the crusading journalist played by Shin Takuma never quite convinces, the fault is in the script not the acting. Overall, I felt that Blackboard is no overlooked masterpiece, but certainly contains enough good work to be worth seeing.

His subsequent film appearances have been few and most of his work has been on stage and TV.

March 14, 2022

Bridge of Japan / 日本橋 / Nihonbashi (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #16

Chikage Awashima

Chikage AwashimaKon Ichikawa’s first film in colour stars three of Japan’s most popular actresses of the era as a trio of suffering geisha during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Okoh (Chikage Awashima) is being pestered by the obsessive Igarashi (Eijiro Yanagi), a former seafood seller from Hokkaido who is nicknamed ‘Red Bear’ as he constantly wears a disgusting bear skin. Having spent all his money on his hopeless love for Okoh, he finds a cheap source of food in the grubs he finds wriggling around in his bizarre garment.

Eijiro Yanagi as 'Red Bear'

Eijiro Yanagi as 'Red Bear'Okoh’s rival is Kiyoha (Fujiko Yamamoto), who has a less revolting suitor in the well-dressed and educated Katsuragi (Ryuji Shinagawa), although he states rather disconcertingly that he yearns to marry her because she reminds him of his missing sister. Unfortunately, Kiyoha has a ‘sponsor’ with whom she has an illicit child, so she’s in no position to marry.

Fujiko Yamamoto and Ryuji Shinagawa

Fujiko Yamamoto and Ryuji ShinagawaDespite being a humourless, self-pitying dullard with a sister fetish, Katsuragi attracts the attention of Okoh while he’s surreptitiously throwing some clams and sea snails off a bridge for incomprehensible reasons; naturally, she falls instantly in love with him. Meanwhile, Okoh’s naïve young friend and colleague Ochise (Ayako Wakao) is bullied in the street by a gang of boys before being rescued by a mysterious monk.

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoIchikawa had just received a bashing from the press after his previous film, Punishment Room, had caused a Clockwork Orange-type controversy when it was blamed for inspiring a spate of crimes in which women had been drugged and raped. His choice of Bridge of Japan for his next project suggests that he had no wish to court such controversy and wanted to play it safe. The source is a 1914 novel by Kyoka Izumi,who adapted it into a play the following year. A 1929 silent version by Kenji Mizoguchi is now lost. In complete contrast to Punishment Room, Bridge of Japan is a sentimental melodrama which must have seemed somewhat old-fashioned even at the time, and it may well be the case that Ichikawa was more concerned with the visual aspects of his first colour film than the content. However, it does look beautiful and is, of course, very well-made and well-acted, with enough quirky elements to maintain interest.

In terms of acting, the female stars all acquit themselves admirably; although Ayako Wakao has the more minor of the three roles, her skill is evident in a scene in which she chats with her grandfather while cooking a meal and doing all sorts of complicated things with the props. Perhaps this unusual adeptness caught the attention of the Assistant Director – Yasuzo Masumura, who would soon go on to become an important director himself and cast Wakao in leading roles in no less than 20 of his films. The picture really belongs to Chikage Awashima, though. I’ve seen her in quite a few films, but often in supporting roles; she really rises to the occasion here, giving a memorable portrait of a fragile and emotionally-needy woman doomed to attract the wrong kind of man.

Izumi was also responsible for the originals on which Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Downfall of Osen (1934), Masahiro Shinoda’s and Takashi Miike’s versions of Demon Pond (1979 and 2005) and Seijun Suzuki’s Kagero-za (1981) were based. Nihonbashiremains untranslated, but the University of Hawaii Press have published two collections of his stories in English.

The play starred male actor Shotaro Hanayagi in the leading female part. Hanayagi made a handful of movies in later years, most notably playing the lead in Mizoguchi’s The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums.

March 5, 2022

Bonchi (The Son) / ぼんち (1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #15

Ayako Wakao and Raizo Ichikawa

Ayako Wakao and Raizo Ichikawa

Set in Osaka, Bonchi stars Raizo Ichikawa as Kikuji, a young womaniser who inherits his father’s tabibusiness and has affairs with a number of women (including Ayako Wakao as an 18-year-old geisha with a taste for gaudy jewellery and Machiko Kyo as a teahouse hostess). His mother (Isuzu Yamada) and grandmother (Kikue Mori) are a couple of old connivers obsessed with appearances and tradition. For some reason I was unable to fathom, they kick his first wife (Tamao Nakamura) out when she gives birth to a baby boy. (According to other commentators, the two older women will only accept a female heir in order to maintain their tradition of matriarchal power; this may well be the case, but was unclear to me despite watching with good quality English subtitles). Anyway, their continual interference in Kikuji’s life prevents him from marrying again, and he eventually has a second son by Ponta (Wakao) out of wedlock. The story is told in flashback by a grey-haired Kikuji to a friend (Ganjiro Nakamura).

Around two years prior to the production of Bonchi, Raizo Ichikawa had escaped his regular jidaigekiassignments to play the stuttering trainee monk turned arsonist in Conflagration, an adaptation of Yukio Mishima’s The Temple of the Golden Pavilion directed by Kon Ichikawa (no relation). Although the producers at Daiei had taken some convincing that he had been right for the part, the collaboration had been a happy one and the casting a success. Bonchi was a project based on a then recently-published novel and initiated by Raizo Ichikawa, who took it to Kon Ichikawa and asked him to direct. He agreed and asked his wife and regular screenwriter Natto Wada to adapt Toyoko Yamasaki’s book.

Ayako Wakao and Raizo Ichikawa

Ayako Wakao and Raizo Ichikawa

The story is set mainly during the early Showa period (late 1920s), but Wada contributed the flashback structure and expanded the post-war scenes. This incurred the wrath of Yamasaki, who reportedly tried to stop production after filming had already begun. She subsequently became known for her studies of corruption in institutions in a number of novels which director Satsuo Yamamoto turned into successful films: The Great White Tower, The Family and The Barren Zone. (I wrote about the latter two in my Tatsuya Nakadai biography as he appeared in both. I also read the abridged English translation of The Barren Zone; the style suggested that Yamasaki was a writer of best-sellers rather than highbrow literature. An English translation of Bonchiappeared in the 1980s through various publishers).

Bonchiseems to me to be a comedy rather than a drama, and the tone is light throughout, with a contemporary jazz score providing an ironic counterpoint to the proceedings. The film has a twist ending, but I have to say it’s a twist I completely failed to see the point in. Bonchiwas not selected for release in the West at the time, and it’s not difficult to see why – some Japanese films are perhaps simply too Japanese to travel well. I would say this is a case in point as the story revolves around etiquette and traditions involving concubinage, etc, which I for one found somewhat baffling. Still, it’s a pleasure to watch such a great cast in a well-made film. The character was clearly close to Raizo Ichikawa’s heart, as he also played the role on stage the year the film was released. However, for me, the best performance is by Isuzu Yamada, who here vacillates between domineering malice and childlike sentimentality most convincingly.

Japanese socks which divide the big toe from the other four.

February 24, 2022

Lake of Tears / 湖の琴 / Umi no koto (1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #14

Katsuo Nakamura and Yoshiko Sakuma

Katsuo Nakamura and Yoshiko Sakuma

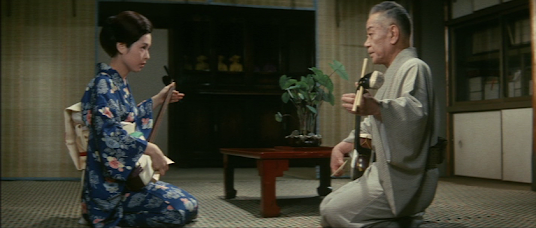

Saku (Yoshiko Sakuma) is a teenage girl who comes to work at a silk farm situated between Lake Biwa and its much smaller neighbour, Lake Yogo, the ‘Lake of Tears’ of the English-language title. This particular silk farm specialises in the making of shamisen strings from silk. The day after her arrival, a young male apprentice named Ukichi (Katsuo Nakamura) arrives and the two soon fall in love. When Ukichi is called up for military service, he stops eating and drinks large quantities of soya sauce in the hope that he will fail the medical and be able to stay with Saku; his scheme fails, but Saku promises to wait for him. In his absence, Monzaemon, a famous shamisen master, pays a visit and takes a shine to her; she is persuaded to leave the silk farm and study the shamisen with him in Kyoto. As the master musician is played by Ganjiro Nakamura – the dirty old man from Odd Obsession and others – it’s no surprise that his interest in Saku is not entirely altruistic, and we’re all set for a tale which seems engineered to fulfil the tragic promise of its title.

Yoshiko Sakuma and Ganjiro Nakamura

Yoshiko Sakuma and Ganjiro Nakamura

Donald Richie once said that the conflict between giri (obligation) and ninjo (inclination) provides the basis of all Japanese drama. ‘All’ might be going a bit far, but Lake of Tears is certainly a prime example of this – the young couple’s plans are ruined due to Ukichi’s obligation to his country and Saku’s obligation to Monzaemon, which puts her in a very difficult position, especially when she incurs the wrath of his jealous mistress (Michiyo Kogure).

Set in the mid-1920s, Lake of Tears is one for those with an interest in the traditional side of Japan, and it’s probably this emphasis which led to it being selected as Japan’s submission for Best Foreign Film at the Oscars that year. Considerable attention is given to details of silk production and the string-making process, while there’s much playing of the shamisen when the story moves to Kyoto.

The film was based on a then newly-published novel written by Tsutomu Minakami, whose stories The Temple of the Wild Geese and Bamboo Dolls of Echizen had already been filmed in Japan and would later be translated into English and published by The Dalkey Archive. In the novel, Saku apparently becomes pregnant by Monzaemon, while in the film it’s merely implied that he has forced himself on her, making her final actions rather baffling. The screenplay is by Naoyuki Suzuki, who had also adapted Minakami’s A House in the Quarter for the same director (Tomotaka Tasaka) in 1963, as well as his Straits of Hunger for Tomu Uchida’s excellent film known in the West as A Fugitive from the Past(1965).

Yoshiko Sakuma (the female lead in Samurai Banners) is ideal as the unfortunate Saku, while Katsuo Nakamura is decent enough in a rather one-dimensional role, but it’s difficult to understand why he won two Best Supporting Actor awards in Japan for his efforts. He was a brother of Kinnosuke Nakamura and is best known abroad as Hoichi the Earless in Kwaidan. The cast also features Kihachi Okamoto favourite Kunie Tanaka and a young Kirin Kikki as fellow silk spinners. Late in her career, Kikki became a favourite of Hirokazu Koreeda and her talent is already evident here from the way she reacts so well to her fellow actors.

Katsuo Nakamura and Kirin Kikki

Katsuo Nakamura and Kirin Kikki

Director Tomotaka Tasaka indulges in some interesting flourishes, at times showing us what his characters are imagining. The most striking example of this is an all-yellow sequence illustrating a fantasy playing out in Monzaemon’s head, while when he improvises a song inspired by Saku, Tasaka cuts to an elaborate montage of flowers and silk-spinning.

Ganjiro Nakamura and Yoshiko Sakuma

Ganjiro Nakamura and Yoshiko Sakuma

I’ve seen two other films by this director (Five Scouts and A Slope in the Sun) and it’s difficult to think of anything they have in common. One interesting fact I managed to uncover is that he was in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing, but was saved from death due to a timely trip to the toilet (although he suffered health issues on and off for the rest of his life as a result of exposure to radiation). Anyway, I would say it is his creativity – along with the excellent colour ‘scope photography of Masahiko Iimura – which makes Lake of Tearsworth seeing despite a sentimental, drawn-out and predictable story.

Confusingly, the Japanese title, Umi no koto, refers to a type of Japanese harp known as a koto.

February 8, 2022

The Hunter's Diary / 猟人日記 / Ryojin nikki (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #13

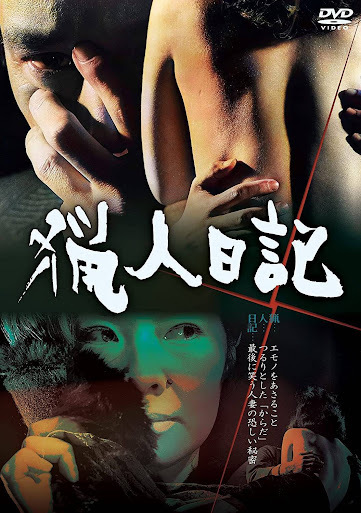

Cover of the Japanese DVD release (no English subtitles)

Cover of the Japanese DVD release (no English subtitles)

This crime mystery from Nikkatsu Studios concerns Ichiro Honda (Noboru Nakaya), a businessman who takes advantage of the travelling necessitated by his job to repeatedly cheat on his wife, Taneko (Masako Togawa), with a series of women he picks up for one night stands. He regards these women as his ‘prey’ and records the details of each conquest in his ‘hunter’s diary’, but when two of these women are murdered, he begins to wonder whether this could really be a coincidence or if somebody’s out to frame him.

Noboru Nakaya as Honda finds his next 'prey'

Noboru Nakaya as Honda finds his next 'prey'

The film begins in documentary style with a lecture on how different blood types can be used to identify criminals, but it ends – surprisingly – with a song, and I found that this unexpected contrast gave the ending an emotional power it would otherwise have lacked. The director, Ko Nakahira, is only familiar in the West for his debut, Crazed Fruit, which saw him labelled as a member of the ‘new wave’ and helped to create the ‘sun tribe’ genre discussed in my last review (for Season of the Sun). He had previously worked as an assistant for Akira Kurosawa on Scandal (1949) and The Idiot (1951); the two filmmakers reportedly enjoyed a good relationship which continued for many years. Aside from Crazed Fruit, I have seen one other Nakahira film, the terrific Mikkai aka The Assignation / Secret Rendezvous (1959), a drama of infidelity with a truly shocking denouement. In The Hunter’s Diary, he uses a combination of real locations and studio work to have fun with a clever but implausible mystery. In 1967, Nakahira began travelling to Hong Kong to make films for the Shaw Brothers, including a remake of The Hunter’s Diary under the title Lie ren (aka Diary of a Ladykiller). He was dismissed from Nikkatsu in 1968 for drinking on the job while directing The Spiders’ Great Advance, a vehicle for Japanese Beatles clones The Spiders. Forced to go independent, his output dwindled and he managed to complete only six films in the 1970s before his premature death from cancer in 1978.

Honda appears to have been a rare starring role for actor Noboru Nakaya, although he played a couple of other leads for Nakahira around this time. Nakaya was married to Kyoko Kishida (star of The Woman in the Dunes), but in the film his character’s wife – an artist who paints bizarre pictures in the style of Dali – is played by Masako Togawa in her only major film role. Togawa was the author of the novel upon which the film was based and was also a well-known singer. She gives a strong performance in the film while Nakaya, though an able enough actor, is perhaps a little nondescript. Also notable among the cast are Shohei Imamura favourite Kazuo Kitamura as a genial lawyer and Yukiyo Toake, who is wonderfully expressive as his naïve assistant.

Kazuo Kitamura and Yukiyo Toake

Kazuo Kitamura and Yukiyo Toake

There is much to enjoy here, so let’s hope that the film gains a wider audience and more of Ko Nakahira’s work surfaces outside Japan.

Seen in a 35mm print with English subtitles at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, on 6 February 2022.

February 3, 2022

Season of the Sun / 太陽の季節 / Taiyo no kisetsu (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #12

Yoko Minamida and Hiroyuki Nagato

Yoko Minamida and Hiroyuki Nagato

A bit of background may be useful here, so please bear with me before we get to the actual film…

Shintaro Ishihara, who died at the age of 89 two days before I write this, was a far-right politician who served as Governor of Tokyo from 1999-2012. He was also a writer who had won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize whilst still a student in 1956 for his short story Season of the Sun. This was a controversial choice and the prize jury themselves had been divided over the selection.

Having just read the English translation published by Tuttle in 1966 under the new title Season of Violence, I personally felt the story to be devoid of literary merit and found it more akin to a hastily-written first draft of a synopsis than a finished work of literature. If it has any value, it’s in the portrayal of a certain type of post-war Japanese teenager which became known as the ‘sun tribe’. These were the sons and daughters from well-to-do families who approached life with little concern for morality, living only to indulge their own hedonistic impulses. While Ishihara does not necessarily glamorise these characters, he certainly refuses to take a disapproving stance in regard to their casual cruelty and promiscuity. It was this that led Ishihara’s work to find favour with another right-wing writer with similar thematic concerns (the more talented Yukio Mishima), but also raised the hackles of the older generation, and there is some evidence to suggest that a certain amount of young Japanese at the time saw the ‘sun tribe’ life as something to aspire to. The controversy was, of course, great publicity for Ishihara, and the film rights to his story were immediately snapped up by Nikkatsu, who wasted no time in producing their adaptation.

With the exception of one notorious sexual scene which had to be omitted, the film is faithful to the story and even adds a little flesh to the bones. Tatsuya is a student who abandons basketball in favour of boxing. Despite his young age, he’s already a womaniser, but meets his match when he becomes involved with Eiko, a young woman who claims she’s unable to fall in love. They have an on-again, off-again relationship, which at one point sees Tatsuya (without Eiko’s knowledge) taking 5,000 yen from his brother, Michihisa, in exchange for leaving the two alone so that Michihisa can attempt to seduce her. The story is apparently based on gossip related to Ishihara by his brother, Yujiro.

Tatsuya is played by Hiroyuki Nagato, best-known in the West as the lead in Shohei Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships, a film in which his co-star, Yoko Minamida, also appeared. Season of the Sun was their first picture together, but far from their last – they became a couple and went on to co-star in around 25 films. Fortunately, they were also more faithful than their on-screen counterparts; they married in 1961, remaining so until Minamida’s passing in 2009.

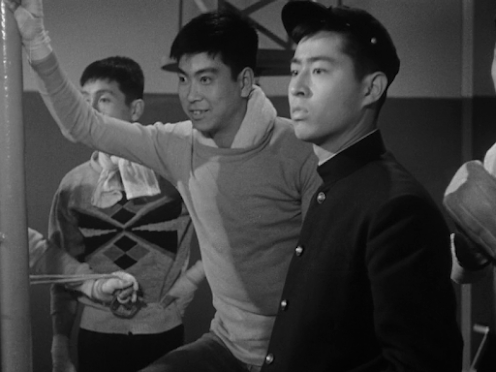

Tatsuya is played by Hiroyuki Nagato, best-known in the West as the lead in Shohei Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships, a film in which his co-star, Yoko Minamida, also appeared. Season of the Sun was their first picture together, but far from their last – they became a couple and went on to co-star in around 25 films. Fortunately, they were also more faithful than their on-screen counterparts; they married in 1961, remaining so until Minamida’s passing in 2009.  Yujiro Ishihara (centre) in his film debut.

Yujiro Ishihara (centre) in his film debut.

Season of the Sun is also notable for marking the film debut of Yujiro Ishihara, the brother of Shintaro, who appears in a small role as a fellow member of the boxing team, while Shintaro himself is briefly seen as a footballer. When Shintaro’s story Crazed Fruit was to be filmed the same year, he insisted that Yujiro be cast in the lead. The studio agreed and Yujiro Ishihara rapidly became one of Japan’s biggest movie stars as a result. Meanwhile, Shintaro Ishihara also played the lead in a couple of films, but was a good deal less successful – the response to his performance in A Dangerous Hero(Kiken na eiyu, 1957) was so poor that it effectively ended his film career.

Shintaro Ishihara in his cameo as the footballer.

Shintaro Ishihara in his cameo as the footballer.

The director of Season, Takumi Furukawa, enjoys little in the way of reputation, although his later picture Cruel Gun Story(Kenju zankoku monogatari, 1964) popped up in Criterion’s Nikkatsu Noir box set some years ago. However, he makes good use of some still-life shots while staging all scenes effectively. Even if it’s not as strong a piece of work as Ko Nakahira’s Ishihara adaptation (the aforementioned Crazed Fruit), the film certainly impressed me more than the original story. Another plus is Masaru Sato’s restrained Spanish guitar score, which makes a nice change from the typical orchestrated movie music and may have begun the vogue for Spanish guitar in Japanese films of this period. Although the characters in the film seem shallow and unlikeable at first, the strong performances from the two leads lend them some much-needed depth and suggest an emotional vulnerability and confusion bubbling away beneath the surface.