M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 20

July 28, 2022

With My Husband's Consent / 『女の小箱』光文社 / Otto ga mita 'Onna no kobako' yori (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #30

By 1964, Ayako Wakao was around halfway through her 20 films for director Yasuzo Masumura. She had graduated to more serious, mature roles two collaborations earlier with Masumura’s A Wife Confesses (1961), saying goodbye to the cheerful young ingénues she had played in their first films together.

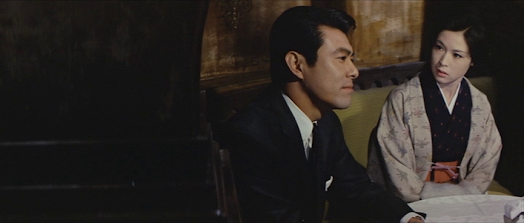

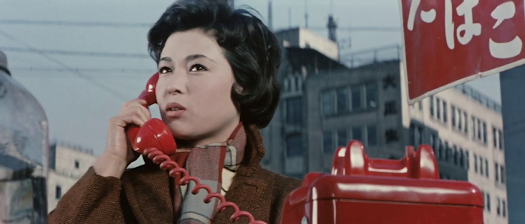

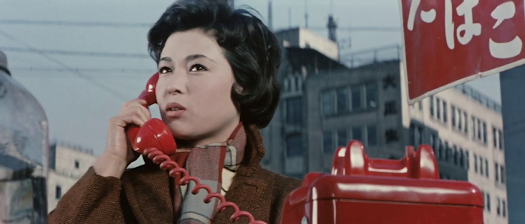

In With My Husband’s Consent, Wakao plays Namiko, the unhappy wife of salaryman Seizo Kawashiro (Keizo Kawasaki), who is seldom at home due to the demands of his job. Kawashiro has been instructed by his boss to prevent the company from being taken over by an outsider buying up shares. Bored and frustrated, Namiko goes out to a bar with a friend one night and attracts the attention of the wealthy owner, Kenichiro Ishizuka (Jiro Tamiya), unaware that he wants to use her to gain information about her husband’s company. Ishizuka is an unscrupulous man who is also having an affair with the bar manageress, Yoko (Kyoko Kishida).

Ironically, Kawashiro is also trying to gain information about Ishizuka by starting an affair with Ishizuka’s secretary, Emi (Kyoko Enami). Ishizuka gets wind of this and informs Namiko of her husband’s infidelity, giving her the address of a hotel where he can be found with his mistress. Namiko goes there and catches Kawashiro in bed with Emi. Later, Kawashiro comes home and tries to excuse his behaviour by saying that he was only doing it for work reasons, but Namiko refuses to accept this, so he slaps her around. When Emi is found murdered at the hotel, Namiko takes revenge by informing the police that her husband had been with Emi on the night of the murder. Although the police do not arrest him, Kawashiro’s job comes under threat when his boss hears he is a suspect. Meanwhile, Ishizuka’s interest in Namiko has become more serious and he proposes that she leave her husband and marry him.

On her return home, Namiko is confronted by her husband, who has discovered that she told the police about him, and he rapes her. Later, he is repentant and begs her to use her relationship with Ishizuka to persuade him to abandon his plans to take over the company. Namiko agrees to this but also decides to leave her husband and accept Ishizuka’s offer of marriage, but finds that Yoko is not inclined to give up her lover so easily.

Based on a then recently-published novel by Jugo Kuroiwa (1924-2003) entitled On'na no kobako (A Woman's Casket / Box), this is another misanthropic drama of infidelity and betrayal in the vein of Masumura’s earlier films Hanran and Stolen Pleasure, although in this case we do have at least one almost entirely sympathetic character in Namiko. As the film is in no way a crime thriller, the murder of Emi seems rather out of place, while the choice of music is unusual – Tadashi Yamauchi’s melancholy strings lend an air of detachment and inevitability to the unfolding tragedy and are almost only heard when Wakao is on screen. This initially works well but, by the end of the film, I felt that the effect had become repetitive and overused. Tomohiro Akino’s cinematography also takes quite a stylised approach, with walls and items of furniture often taking up nearly half of the widescreen frame, suggesting that Masumura wanted to give the impression of having his characters squashed uncomfortably together.

Although some Japanese films notoriously feature actors slapping each other for real, the slapping in this film is rather poorly done – it’s obvious there’s no contact, yet we’re treated to a sound effect that sounds like a whiplash on sheet metal. It’s nice to know that nobody slapped Ayako Wakao though. I suspect a body double was also used for some of her scenes here.

Wakao with Kyoko Kishida

Wakao with Kyoko KishidaJiro Tamiya is an actor I think I have only ever seen playing ruthless types in films such as Satsuo Yamamto’s The Great White Tower and, for Masumura, Black Test Car and Stolen Pleasure, and it’s business as usual for him here. Despite her good looks, Kyoko ‘Woman in the Dunes’ Kishida somehow has a great face for playing slightly mad characters and she also lives up to expectations in this case. She was quickly reteamed with Wakao and Masumura for Manji (also 1964). However, Masumura regular Keizo Kawasaki seemed a little over the top to me, especially in comparison to the admirably restrained Wakao, but on the other hand I hated his character so much it could equally be argued that he is highly effective!

Overall, I would say that With My Husband’s Consent is not top-rank Masumura, but it’s certainly a strong second-tier effort. Watched without subtitles. DVD at Amazon JapanIt’s unclear from the film which meaning is intended.

July 19, 2022

Beauty is Guilty / 美貌に罪あり / Bibo ni tsumi ari (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #29

Ayako Wakao’s fourth film for director Yasuzo Masumura is the sort of soapy drama that would soon disappear from cinema screens in Japan and be produced for TV instead. Nevertheless, it has a very strong cast and some depths which may not be immediately apparent.

Haruko Sugimura

Haruko SugimuraFusa (Haruko Sugimura) is a widow who owns an orchid farm near Tokyo which has been the family business for 150 years but is now struggling financially. Another difficulty is the fact that her two grown daughters have other ideas about what they want to do with their lives. The eldest, Kikue (Fujiko Yamamoto), wants to be a dancer. She is the protégé of dancer and teacher Kanzo (Shintaro Katsu), and the two become romantically involved with the result that Kanzo’s patroness and former mistress, restaurant owner Okume (Chieko Murata), throws them out in a jealous rage. The two are forced to move into a small apartment and dance at parties to make ends meet.  Fujiko Yamamoto

Fujiko Yamamoto

Meanwhile, Kikue’s younger half-sister Keiko (Ayako Wakao) becomes an air stewardess and abandons her childhood sweetheart Tadao (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), who is employed on her mother’s farm. Keiko begins running with a more sophisticated, urban crowd but narrowly escapes being raped by a smooth-talking embezzler she meets at a party.  Hiroshi Kawaguchi

Hiroshi Kawaguchi

Tadao’s younger sister, Kaoru (Hitomi Nozoe), is a deaf-mute who also works on the farm and is treated by Fusa as a third daughter. She has a crush on orchid expert Shusaku (Keizo Kawasaki), but unfortunately he is in love with Kikue (and unaware she is already in a relationship with Kanzo).

Hitomi Nozoe

Hitomi NozoeBeauty is Guilty is about coming to terms with a changing world. Kikue, played by an actress said to have embodied the ideal of Japanese beauty, studies and performs classical Japanese dance and represents traditional values. In contrast, Keiko (played by an actress with more contemporary-looking features) clearly has her eye on the future in going to work for an airline and represents modern values (Ayako Wakao even speaks English a couple of times here).  Shintaro Katsu

Shintaro Katsu

Kaoru, continually having her hair stroked or being patted on the head by those around her, is a less convincing character as I doubt someone in her position in reality would appreciate being treated as if she were a puppy. Playing a dancer, Shintaro Katsu is so well-groomed he may be unrecognisable to anyone who has only seen him as Zatoichi. As the kind but somewhat resigned matriarch, Haruko Sugimura gives her usual quietly impressive performance and the spontaneous dance she performs with Fujiko Yamamoto is a strangely moving highlight.

Beauty is Guilty was based on a novelby Matsutaro Kawaguchi (1899-1985), who frequently wrote for Kenji Mizoguchi and was the father of Hiroshi Kawaguchi, who appears here as Tadao. The novel was adapted by Sumie Tanaka (1908-2000), a female playwright who later became a screenwriter, notably for directors Mikio Naruse and Kiuyo Tanaka (no relation).

I would be surprised to see a DVD release of this one in the West as it fails to tick any of the cult boxes of those Masumura films which have surfaced over here.

Watched without subtitles.I haven’t been able to find any details of the novel even in Japanese, so it may actually have been a short story or published under a different title.

July 15, 2022

Twilight Saloon / たそがれ酒場 / Tasogare sakaba (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #28

Left to right: Jun Tatara, Daisuke Kato and Eijro Tono

Left to right: Jun Tatara, Daisuke Kato and Eijro Tono

Depicting the shattered dreams of a disparate range of characters struggling to survive in the chaos of post-war Japan, Tomu Uchida’s second film after a hiatus of over a decade spent in exile may well be his most personal work. Twilight Saloon takes place entirely inside a bar during the course of one day from the start of business until closing time. Entertainment is provided by veteran pianist Eto and his young singer and protégé, Kenichi (played respectively by real-life musicians Hiroshi Ono and Takuya Miyahara in their only film roles). Both are down on their luck, as is stripper Emy Rosa (Keiko Tsushima), who began her career as a ballet dancer, but now provides the bar’s most popular part of the show.

Keiko Tsushima

Keiko Tsushima

Meanwhile, waitress and singer Yuki (Hitomi Nozoe, star of Yasuzo Masumura’s Giants and Toys) loves Masumi (Ken Utsui) but has unfortunately attracted the attention of yakuza Morimoto (Tetsuro Tanba), who won’t take no for an answer.

Hitomi Nozoe

Hitomi Nozoe

Tetsuro Tanba (seated) and Ken Utsui (right). Takuya Miyahara and Hitomi Nozoe are in the back ground.

Tetsuro Tanba (seated) and Ken Utsui (right). Takuya Miyahara and Hitomi Nozoe are in the back ground.

Other customers include a group of beret-wearing pseudo-intellectual beatniks who prattle about existentialism, and gambler and ex-soldier Kibe (Daisuke Kato), who is surprised when his former commander, Colonel Otsuka aka ‘The Demon’ (Eijiro Tono), walks in. Otsuka is an embittered man who claims to be working as a real-estate broker but is clearly short on funds. However, the most important character is Umeda, a regular who used to be a painter but now makes a living of sorts playing pachinko. From his usual stool at the end of the bar, Umeda regards the tragedies that unfold around him with kindness and pity and is quick to help those in need when he can.

Isamu Kosugi

Isamu KosugiUmeda is memorably played by Isamu Kosugi,star of many of Uchida’s pre-war films, in his only appearance in the director’s post-war work. The character must have had a great deal of resonance for both star and director – at one point, he talks of how he gave up painting due to feelings of guilt for having glorified war in his work. Kosugi had appeared in a number of propaganda films during the war years, while in 1942 Uchida went to China to work for the Manchukuo Film Association, a company which produced mainly pro-Japanese propaganda. Although Uchida apparently never completed a film for the company himself, it is clear that he later regarded this decision as a grave error of judgement on his part. Towards the end of Twilight Saloon, Umeda tells the pianist Eto, ‘We have to overcome resentment and sorrow,’ which I suspect was the main message that Uchida wished to convey in this film.

Despite the unlikely incongruity of a bar offering an entertainment programme which begins with opera and ends in a strip show, the film has much to recommend it. Uchida's co-ordination of the many characters and story threads is impressive, as is his use of a single set, which he inventively exploits to maximum advantage. The way in which major characters continue to do their thing in the background while the focus is on somebody else is especially good. One bizarre highlight is Kenichi’s rendition of ‘The Toreador Song’ from Bizet’s Carmen, during which Umeda and the bar’s resident freeloader Kurishima, aka ‘Suckerfish’ (Jun Tatara), break into a spontaneous dance with Umeda as the toreador and Suckerfish as the bull.

Isamu Kosugi and Jun Tatara

Isamu Kosugi and Jun TataraThe screenplay of Twilight Saloon is by Senzo Nada, a name with no other credits on IMDb. Tempting as it is to conclude that this is Uchida working under a pseudonym, the evidence refutes this; as David Baldwin has pointed out in his piece on his Uchida website (see below), Nada does have a few other credits on the Japanese Movie Database. Furthermore, when I dug a little deeper, I found information suggesting that Nada had been a novice screenwriter at the time and that his script somehow found its way to Uchida, with whom it obviously struck a chord. How much the director may have altered it is, of course, anyone’s guess. Nada also wrote for television and a collection of his screenplays was published in 1986. One Japanese source states that he was born in 1931 and died in 1985, while another (probably more reliable) gives his date of birth as 1918, but seems to agree with the year of death. I also found a list of TV credits for Nada, which include a new adaptation of Twilight Saloon made in 1961 and running 45 minutes; the following year, Uchida directed a TV adaptation of his 1939 film Earth, for which he employed Nada to write the script.

For more on Twilight Saloon and Tomu Uchida, please visit http://www.uchidatomu.com/twilight-saloon-tasogare-sakaba-1955/

Kosugi became a director of B-movies after the war while continuing his acting career.

July 4, 2022

Hanran / 氾濫 ('Deluge', 1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #27

Ayako Wakao, Shin Saburi and Sadako Sawamura

Ayako Wakao, Shin Saburi and Sadako Sawamura

There’s not much of a role for Ayako Wakao in her third film for director Yasuzo Masumura. She appears (rather than ‘stars’) as Takako, the carefree daughter of Sahei Sanada (Shin Saburi), an employee who invents a new type of adhesive, as a result of which he is promoted to a highly-paid and important position. This newfound success leads to the reappearance of his former mistress, Sachiko (Sachiko Hidari), who has a young son she claims is his, while a student, Tanemura (Keizo Kawasaki), attempts to ingratiate himself with Sanada in order to pitch his own ideas to the company. Sanada resumes his affair with Sachiko, Tanemura begins one with Takako in order to strengthen his position, and Sanada’s wife, Fumiko (Sadako Sawamura), makes a fool of herself in a liaison with her daughter’s opportunistic piano teacher (Eiji Funakoshi).

Shin Saburi and Sachiko Hidari

Shin Saburi and Sachiko Hidari

Based on a novel by Sei Ito (as was Temptation, featured in my previous post), Hanran is a misanthropic work in which the majority of the characters are portrayed as vain, selfish and two-faced. They engage in a series of shabby betrayals, with everyone cheating on everyone else, while the balance of power between them continually shifts.

Keizo Kawasaki and Ayako Wakao

Keizo Kawasaki and Ayako Wakao

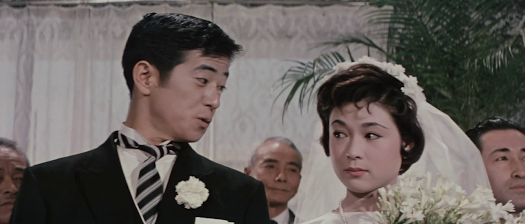

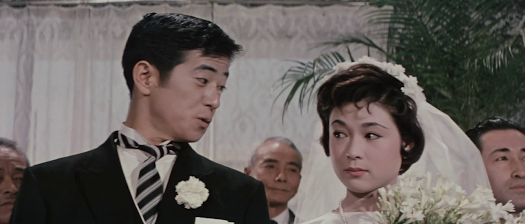

The one character who triumphs at the end is Tanemura – the slimiest and most reprehensible of a pretty unpleasant bunch. He dumps Takako and marries the boss’s daughter. However, his bride seems considerably less enthusiastic about the marriage than he, and Masumura implies that Tanemura’s victory will be short-lived; the newlyweds climb to the top of a gas storage tank, where the film ends in a heavily symbolic shot – Tanemura might be top of the world à la James Cagney in White Heat, but we all know what happened to him.

Hanran is surprisingly dull for a Masumura film, and fans of Ayako Wakao and Sachiko Hidari will be disappointed that neither have a great deal of screen time, while Shin Saburi is perhaps too low-key in the leading role. The colour photography looks a little cheap, which is not uncommon for a Japanese film of this period – Akira Kurosawa reportedly held out against the use of colour until Dodes’ka-den (1970) due to concerns about the quality of colour processes in Japan. Matters are not helped by Tetsuo Tsukahara’s jazz guitar score, which is intrusive and a little irritating in its incessant noodling.

A scene in which Tanemura takes Takako to a private room in a restaurant then slaps her into sexual submission is all too familiar in Japanese films, I’m sorry to say, and I wonder how many women have been knocked about in real life as a result of such misogynistic scenes.

Watched without subtitles.

June 23, 2022

Temptation /誘惑 / Yuwaku (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #26

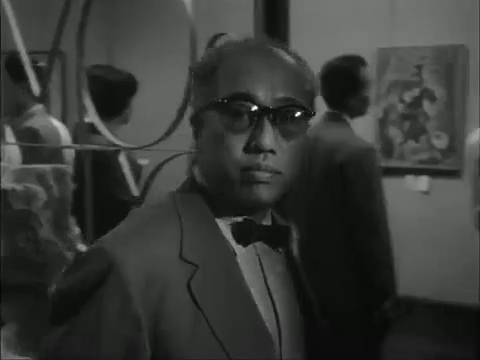

Koreya Senda

Koreya Senda

In order to avoid preconceptions, I try to read as little as possible about a film prior to watching it, but I usually have a rough idea of the genre at least. However, in this case I was way off as I had expected Temptation to be a crime thriller, but it turned out to be a sentimental romantic comedy. I think the title had conjured up images of a femme fatale enticing some poor sap to his doom, but there is nothing of the kind to be found in Temptation, and even after watching it I’m far from sure of the reason for the title.

This Nikkatsu production provides a rare leading role on film for Koreya Senda, founder of the left-wing Haiyuza theatre company and mentor to Tatsuya Nakadai, no less. Despite being billed sixth (a reflection of his non-film-star status), the film revolves around his character: Shokichi Sugimoto, a rather vague 55-year-old widower who owns a clothing store in Ginza, where he lives with Hideko, his unashamedly materialist daughter.

Hideko is played by top-billed Sachiko Hidari, best-known for later films such as The Insect Woman (1963) and Under the Flag of the Rising Sun (1972). In contrast to the serious actress she later became, the younger Hidari seen here is typical of her earlier screen persona: lithe, petite, cheerful and fast-talking. In real life, she was of a more sober temperament; a highly intelligent feminist, she later directed a film of her own, The Far Road (1977).

For some reason, her father decides to open a gallery above the store and launch it with a show organised by Hideko featuring the work of her avant-garde artist friends, an assortment of female ikebana artists and male painters. He thinks it might be about time that Hideko found a husband, while she is beginning to think her father should remarry. In reality, he is still moping about a lost love from 30 years ago; meanwhile, an unlikely romance develops between a gauche female shop assistant and one of Hideko’s bohemian friends, a brilliant but scruffy artist who has lice.

Also notable in the cast are Shoichi Ozawa (star of Imamura’s The Pornographers), who generates many of the laughs as a naïve shop assistant, and Izumi Ashikawa, the ‘Audrey Hepburn of Japan’ who turns up towards the end as the daughter of Sugimoto’s lost love.

Temptationis an odd little film – it’s difficult to see what the point of it all is, or who the intended audience could have been, and the beret-wearing artist types depicted in the film never quite convince. However, its origin as a just-published novel of the same title by Sei Ito, a modernist writer in vogue at the time, probably explains its reason for existence. In any case, director Ko Nakahira certainly keeps things moving along and throws every piece of quirkiness and slapstick he can at it. Inevitably, this approach is hit and miss, but the film is mostly quite charming and fun, although definitely the least impressive of the four I’ve seen by Nakahira (the others being Mikkai, The Hunter’s Diaryand Crazed Fruit).

Ikebana fans should look out for a cameo by Sofu Teshigahara as himself; the founder of the Sogetsu school of ikebana and father of Woman of the Dunesdirector Hiroshi Teshigahara, he is also credited as a consultant on Temptation. Well-known avant-garde artists Taro Okamoto and Seiji Togo also appear as themselves. Considering all the avant-garde references throughout, the film features a surprisingly conventional score by the usually out-there Toshiro Mayuzumi.

For a more detailed synopsis of Temptation, see Hayley Scanlon's review at Windows on Worlds.

June 8, 2022

The Most Valuable Wife / 最高殊勲夫人 / Saiko shukun fujin (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #25

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoThe third of the 20 films director Yasuzo Masumura made with star Ayako Wakao is a light comedy featuring Wakao as the third daughter of widower Rintaro Nonomiya (Seiji Miyaguchi), who works as the head of the finance department in a company, but is soon to retire. The family used to be poor, but her two older sisters have helped to lift them out of poverty by both marrying sons of the company’s deceased founder. A third son, Saburo (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), remains single, but Kyoko’s eldest sister Momoko (Yatsuko Tan’ami) conspires to push them together, hoping this will lead to a third marriage and further deepen the ties between the two families. Instead, Saburo and Kyoko realise what Momoko is up to and vow never to get married. Kyoko takes a job as a secretary at the company in order to find an alternative husband and a number of male employees compete for her hand, while she also ends up doing a little matchmaking of her own.

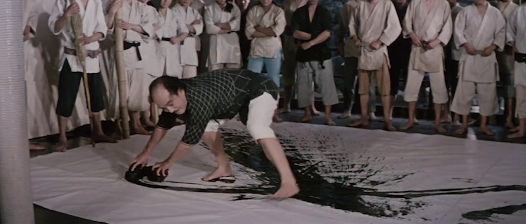

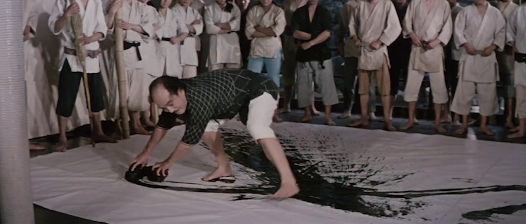

Rin Sugimori as the calligrapher

Rin Sugimori as the calligrapherUnfortunately, the story is far from compelling as it’s obvious from the start that Kyoko and Saburo will end up marrying. Masumura works hard to maintain interest in the paper-thin material, throwing in some amusing comic vignettes featuring random characters such as a Jackson Pollock-inspired performance calligrapher and a schoolgirl singing a jazz number in a deep, masculine voice. However, despite his inventiveness, The Most Valuable Wiferemains a well-made film of little consequence.

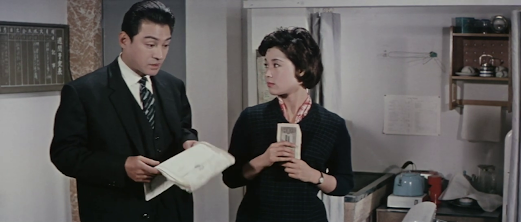

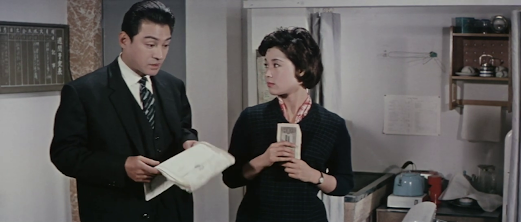

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Ayako Wakao

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Ayako WakaoI’ve never understood the appeal of Hiroshi Kawaguchi, who always played men whom women find irresistible even though he seems to me entirely unprepossessing. However, he starred in 10 films for Masumura and five for Kon Ichikawa before quitting Daiei in 1962 to become a real estate developer. He later returned to acting sporadically and also presented a wildlife show on TV, during which his finger was nearly bitten off by a piranha. He passed away from cancer in 1987 aged only 51.

Eiji Funakoshi and Ayako Wakao

Eiji Funakoshi and Ayako WakaoPlaying the eldest of the three sons in an amusing comic performance is Eiji Funakoshi, who was also frequently employed by both Ichikawa and Masumura. He carved out something of a niche for himself playing philandering husbands who were inept in the workplace, as he does here, but is best-remembered for his atypical role starring in Ichikawa’s nihilistic World War 2 film Fires on the Plain.

Wakao's matchmaking between Katsuhiko Kobayashi and Kazuko Miyagawa

Wakao's matchmaking between Katsuhiko Kobayashi and Kazuko Miyagawa

Although the film hardly provides Ayako Wakao with one of her finest roles, it’s certainly further testament to her versatility. Having watched her recently in Masumura’s far superior Irezumi, it’s hard to believe this is the same woman. But the collaboration between star and director was still in its infancy at this point, and Masumura had yet to cast her in a serious dramatic role.

The Most Valuable Wife / 最高殊勲夫人 / Saiko shukun fujin

Obscure Japanese Film #25

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoThe third of the 20 films director Yasuzo Masumura made with star Ayako Wakao is a light comedy featuring Wakao as the third daughter of widower Rintaro Nonomiya (Seiji Miyaguchi), who works as the head of the finance department in a company, but is soon to retire. The family used to be poor, but her two older sisters have helped to lift them out of poverty by both marrying sons of the company’s deceased founder. A third son, Saburo (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), remains single, but Kyoko’s eldest sister Momoko (Yatsuko Tan’ami) conspires to push them together, hoping this will lead to a third marriage and further deepen the ties between the two families. Instead, Saburo and Kyoko realise what Momoko is up to and vow never to get married. Kyoko takes a job as a secretary at the company in order to find an alternative husband and a number of male employees compete for her hand, while she also ends up doing a little matchmaking of her own.

Rin Sugimori as the calligrapher

Rin Sugimori as the calligrapherUnfortunately, the story is far from compelling as it’s obvious from the start that Kyoko and Saburo will end up marrying. Masumura works hard to maintain interest in the paper-thin material, throwing in some amusing comic vignettes featuring random characters such as a Jackson Pollock-inspired performance calligrapher and a schoolgirl singing a jazz number in a deep, masculine voice. However, despite his inventiveness, The Most Valuable Wiferemains a well-made film of little consequence.

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Ayako Wakao

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Ayako WakaoI’ve never understood the appeal of Hiroshi Kawaguchi, who always played men whom women find irresistible even though he seems to me entirely unprepossessing. However, he starred in 10 films for Masumura and five for Kon Ichikawa before quitting Daiei in 1962 to become a real estate developer. He later returned to acting sporadically and also presented a wildlife show on TV, during which his finger was nearly bitten off by a piranha. He passed away from cancer in 1987 aged only 51.

Eiji Funakoshi and Ayako Wakao

Eiji Funakoshi and Ayako WakaoPlaying the eldest of the three sons in an effective comic performance is Eiji Funakoshi, who was also frequently employed by both Ichikawa and Masumura. He carved out something of a niche for himself playing philandering husbands who were inept in the workplace, as he does here, but is best-remembered for his atypical role starring in Ichikawa’s nihilistic World War 2 film Fires on the Plain.

Wakao's matchmaking between Katsuhiko Kobayashi and Kazuko Miyagawa

Wakao's matchmaking between Katsuhiko Kobayashi and Kazuko Miyagawa

Although the film hardly provides Ayako Wakao with one of her finest roles, it’s certainly further testament to her versatility. Having watched her recently in Masumura’s far superior Irezumi, it’s hard to believe this is the same woman. But the collaboration between star and director was still in its infancy at this point, and Masumura had yet to cast her in a serious dramatic role.

June 4, 2022

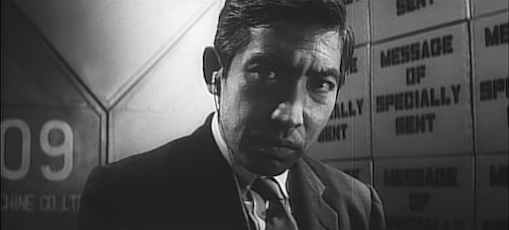

The Eleventh Hour /どたんば/ Dotanba aka They are Buried Alive (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #24

Eijiro Tono

Eijiro TonoBased on a television play by Ryuzo Kikushimawhich was itself based on a true story, this Toei production concerns five coal miners who become trapped underground after a flood and the subsequent attempt to rescue them before they suffocate. One of the endangered miners is played by Kurosawa favourite Takashi Shimura, who seems set up to play an important part, but unfortunately he soon disappears for most of the film as Uchida and co-screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto decide to focus attention on events above ground. Indeed, The Eleventh Hour is not only a film without stars, but also one which lacks any major characters to speak of, and this choice rather dissipates the drama in my view. However, there are certainly some familiar faces among the ensemble, including Eijiro Tono as the bad-tempered foreman and Eiji Okada (who went on to star in Hiroshima Mon Amour and Woman of the Dunes) as the spokesman of a Korean mining team. Okada had apparently worked as a coal miner himself, while Uchida also had experience of working in the mines during the war.

As the fate of the miners hangs in the balance, it sparks a media frenzy and a crowd gathers at the mine while an ice cream seller makes a killing. These scenes briefly recall Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951), but ultimately Uchida’s film has little in common; the reporters portrayed here are polite, respectful, and appear to be genuinely hoping for a positive outcome. Instead, Uchida gives us a surprisingly sentimental and typically Japanese movie in which people have to work together in order to surmount their difficulties and achieve a common goal, although he does add an extra wrinkle; in this case, they also have to overcome their anti-Korean prejudice as they will need the help of the Koreans working at another mine nearby if their rescue efforts are to succeed.

Takashi Shimura

Takashi Shimura

Given that Uchida has made some really excellent films and the script was co-written by the great Shinobu Hashimoto, I had hoped to discover a hidden gem here, but actually found something that more closely resembled a lump of coal – a functional item with little sparkle. The Eleventh Hour is by no means a bad film, and technically the underground sequences are very well achieved (presumably in the studio), but these should have been much more suspenseful, so overall it’s not difficult to see why this particular Uchida film has remained so little-known.

For more on this film, see The International Uchida Tomu Appreciation Society websiteLike Shinobu Hashimoto, Kikushima frequently worked as a screenwriter for Akira Kurosawa. The TV play was broadcast live the previous year on NHK and featured the TV debut of Rentaro Mikuni. As a kinescope recording was made at the time, this work still exists. It was directed by Hiroshi Nagayama, who seems to have no film credits and presumably worked only in television.

May 29, 2022

Stepbrothers / 異母兄弟 / Ibo kyoudai (1957)

Obscure Japanese film #23

Kido (Rentaro Mikuni) with his two eldest boys.

Kido (Rentaro Mikuni) with his two eldest boys. Covering a period of 25 years, Stepbrothers begins in 1921 as we see a military officer returning home on horseback. Upon being greeted by his servant, he dismounts and slaps the poor fellow so hard that he knocks him down. This introduction to Hantaro Kido provides an accurate first impression of a character who is to remain entirely unambiguous. Indeed, Kido proves to be not only an arrogant bully, but a humourless bore to boot. Who better to play him, then, than Rentaro Mikuni, an actor never afraid to be unsympathetic and who even seemed to revel in such roles.

Kinuyo Tanaka in a highly symbolic shot.

Kinuyo Tanaka in a highly symbolic shot.

Kido has two nasty young sons who are chips off the old block and a terminally ill wife who has left him sexually frustrated. When a new maid arrives in the form of Rie (Kinuyo Tanaka), she’s barely begun work before he rapes her in the stable, and his wife passes away soon after. After learning that Rie is pregnant with his child, Kido initially plans to kick her out, but his superior officer hears about the pregnancy and asks him what he plans to do to avoid a scandal. Purely to impress the commander, he says he will marry Rie, and the unfortunate woman is doomed to a life of near-slavery as she has no other options. Another son, Tomohide, soon follows, and both her children are continually treated with contempt by their stepbrothers, although a scene in which one of the elder boys watches Rie laughing and having fun with her two young ones makes it clear that a degree of jealousy is involved. As the years pass, the Second World War begins and the focus of the narrative moves on to the teenage Tomohide (Katsuo Nakamura, who later played Hoichi the Earless in Kwaidan) the only boy in the family who has no wish to be a soldier. Tomohide falls in love with a maid, Haru (Hizuru Takachiho), but she is kicked out by Kido for singing and sold into prostitution (evidently, this was still happening in Japan as late as the 1940s).

Hizuru Takachiho and Katsuo Nakamura.

Hizuru Takachiho and Katsuo Nakamura.

Like the young hero of the only other film I’ve seen directed by Miyoji Ieki, The Wayside Pebble (1964), Tomohide’s life is ruined as a result of living in an oppressive, semi-feudal, patriarchal society. The characters are as black and white as the images themselves, and perhaps it might have been preferable to make them a little more complex, but then again this may have diluted the strength of Ieki’s message that a society founded on such values is ultimately destructive for all involved.

Rentaro Mikuni

Rentaro Mikuni

Kinuyo Tanaka is too old for her role in the early stages, but her casting makes more sense as the years pass. Her appearance remains the same, while Mikuni gradually transforms into a decrepit old git as he would also do in Satsuo Yamamoto’s Ballad of the Cart-Puller a couple of years later. The organ music by Kon Ichikawa favourite Yasushi Akutagawa has a very churchy feel and seems a strange choice, but then again Stepbrothersis certainly a solemn piece of work.

The film is based on a then recently-published novel of the same title by Torahiko Tamiya (1911-88), while the screenplay is co-written by Kenji Mizoguchi’s regular collaborator Yoshikata Yoda (who also wrote the screenplay for the aforementioned Ballad of the Cart-Puller) and the lesser-known Nobuyoshi Teruda. Stepbrothers shared the main prize at Czechoslovakia’s Karlovy Vary International Film Festival with Sergei Gerasimov’s epic And Quiet Flows the Don.May 19, 2022

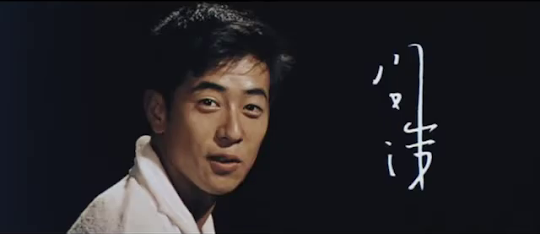

Hymn to a Tired Man / 日本の青春 / Nihon no seishun / Youth of Japan (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #22

What a treat to finally see one of Masaki Kobayashi’s lost films! Hymn to a Tired Man is based on a 1967 novel by Shusaku Endo entitled Dokkoisho. Endo (a Catholic) is best-known outside Japan as the author of Silence, filmed by Masahiro Shinoda in 1971 and again in 2016 by Martin Scorsese (whose version was a great improvement on that of Shinoda). He is also one of the most widely-translated of Japanese writers, although Dokkoisho has yet to appear in English. Having read a number of Endo’s books in translation, I suspect that Kobayashi’s film is quite faithful to the original as it contains a number of themes, concerns and characteristics I recognised from those works, such as a preoccupation with the struggle to be good in a world within which evil always seems to prevail. Of course, this has also been a theme of Kobayashi’s in films such as The Human Condition and Harakiri, so the combination of Endo and Kobayashi makes a great deal of sense and it’s only surprising that the director did not adapt other works by this author.

Michiyo Aratama and Makoto Fujita

Michiyo Aratama and Makoto Fujita

The film opens with scenes of the middle-aged, overworked Zensaku (Makoto Fujita) enduring a variety of annoyances on his daily commute to the accompaniment of some sardonic narration by Masao Mishima which seems to suggest we’re in for a comedy. However, despite a further comic scene involving a ludicrous invention for repelling perverts on the tube (Zensaku works in a patent office), the tone soon turns serious as this apparently walking-dead non-entity finds himself suddenly confronted with the past in the shape of the fiancée from whom he had been separated during the war (Michiyo Aratama) and the officer who had beaten him so badly that it had permanently damaged his hearing (Kei Sato). Zensaku’s dull life is turned upside down by the reappearance of these two, while a number of flashback sequences increase our understanding and sympathy for this unlikely hero as he contemplates leaving his unhappy marriage and struggles to be a good parent to his directionless son (Toshio Kurosawa), who is flirting with becoming a member of Japan’s Self-Defence Force.

Unfortunately for Kobayashi, such themes proved to be box office poison and this film damaged his career, perhaps explaining why it has languished in obscurity for so long. It’s certainly true that the film has a number of flaws. Typically for an Endo story, we have a protagonist haunted by the past and afflicted by guilt, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the film becomes a little too talky at times in its efforts to express Endo’s themes and explain the characters’ motivations. There is also a coincidence or two too many in the story. Furthermore, although Kobayashi enlisted his brilliant regular composer Toru Takemitsu, this is far from Takemitsu’s best work and the use of a harmonica in several sequences feels decidedly out of place, while the misleadingly comic beginning also seems an odd choice. Nevertheless, as one would expect from this director, he delivered a very well-made film which tells a moving story, offers plenty of food for thought and characteristically lifts the rug to expose the dirt swept under it, so to speak – the dirt, in this case, being represented by Kei Sato’s portrayal of a war criminal turned successful (and untouchable) businessman, a figure we can safely assume is intended as more than a mere isolated example. The flashbacks depicting his treatment of Zensaku instantly recall scenes from Kobayashi’s monumental trilogy The Human Condition, and it’s clear that the director relates strongly to Zensaku just as he did to Kaji, portrayed by Tatsuya Nakadai in the aforementioned trilogy.

The performances by the three principals are excellent, with Makoto Fujita a revelation as Zensaku – I believe he was best-known for playing comic parts on television, and Kobayashi probably took a considerable risk in casting him for such an important role, but he pulls it off very well indeed and ages most convincingly. His portrayal of a downtrodden man who has been called a coward so often (simply for refusing to be a bully) that he has come to believe it himself is genuinely touching. Throughout his life, Zensaku consistently does what he believes to be the right thing, often at considerable personal cost and without seeking any glory – if that’s not bravery, then what is?, Kobayashi seems to ask. Plenty of reasons, then, why Hymn to a Tired Man is well worth seeking out. The copy I saw looked like a VHS transfer, so let’s hope somebody remasters it for digital and gives it some proper distribution.

According to Stephen Prince in his book A Dream of Resistance – The Cinema of Masaki Kobayashi, ‘dokkoisho’ is a ‘phonetic rendering of the groan that Zensaku makes as he sits down with fatigue.’