M.R. Dowsing's Blog

September 28, 2025

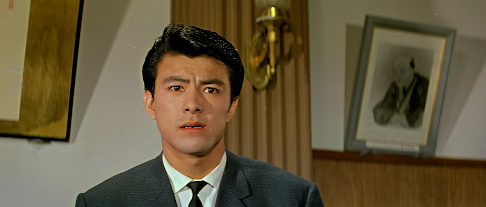

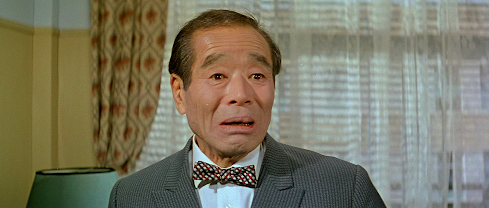

Kirai Kirai Kirai / 嫌い嫌い嫌い / (‘Hate hate hate’, 1960)

Ichiro Sugai

Ichiro Sugai

Sojuro Shinkawa (Ichiro Sugai) is the elderly chairman of theShinkawa conglomerate, a position which he was hoping his son, Sotaro (KenjiSugawara), would succeed him in. However, Sotaro has rebelled and gone off todo his own thing, so Sojuro gathers the presidents of the six companies whichmake up the conglomerate and asks them each to select their most promising employeeand send them to head office, where they will compete to marry hisgranddaughter, Kikuko (Atsuko Kindaichi), and the winner will be groomed tobecome the new chairman.

The six men chosen run the gamut from the ultra masculine Nagaoka(Ryuichi Ishii) with his impressive chest hair to the effeminate Hirose (KanjiMatsumoto), who drinks only milk, a thermos of which he always carries withhim. Other candidates include Sakurai (future director Juzo Itami), who used tobe friends with Kikuko as a child, the handsome and modest Tsujimoto (JiroTamiya), who appears to be the favourite, and coal miner Fukumitsu (GenMitamura), who is conflicted due to his secret love for co-worker Sumiko (JunkoKano)…

This Daiei production was based on a novel entitled Hana no sarariman (‘The Flower Salaryman’)by Keita Genji (1912-85), a writer well-known for this type of material whosework also provided the basis for many other films including Masumura’s Blue Sky Maiden (1957) and The Most Valuable Wife (1959).

For me, the main appeal was that it provided a rare chance to seeanother film by Hiroshi Edagawa, whose RosesBloom on The Rose Bush (1959) I liked so much. However, this one is less interestingas it’s basically a piece of fluff, albeit a well-made one which is notunentertaining. It’s an ensemble piece with no real star at the centre,although Jiro Tamiya and Junko Kano were both beginning to get popular at thetime and Sachiko Hidari also appears prominently, although in a role that haslittle bearing on the story, while Kazuko Matsuo pops up singing the title songin a nightclub (to which you can listen on YouTube here). Even Bokuzen Hidarimakes an appearance as one of the company presidents - which may well be themost untypical role he ever played. Anyway, for the most part, it's a pleasant enoughtime-passer, though the gay stereotyping of Kanji Matsumoto’s character isregrettable.

A note on the title:

Kirai can also be translated as ‘I hate it’, ‘I hate you’, etc, so the tagline on the Japanese posters should probably be read as ‘I hate him because he’shandsome! I hate him because he’s rich! I hate him because he has chest hair!Is that really true?’

Kazuko Matsuo

Kazuko Matsuo

Watched with dodgy subtitles.

September 23, 2025

The Seasons of Love / 四季の愛欲 / Shiki no aiyoku (‘Four Seasons of Love’, 1958)

Shoji Yasui

Shoji Yasui

Gyo (Shoji Yasui) is a famouswriter married to self-centred model Ginko (Yuko Kusunoki), but their marriageis not registered and they have told few people about it, fearing that to makeit public might damage their careers. Ginko hates Gyo’s mother, Urako (IsuzuYamada), believing that she abandoned Gyo when he was a child and only got backin touch after he became famous so she could sponge off him. Now 48, Urako is awidow, but in many ways she behaves like a young woman and has a lover,Hirakawa (Tomo’o Nagai), who owns a fabric wholesale business (at one point, sheeven takes him to see a blue movie).

Yuko Kusunoki

Yuko Kusunoki

Tomo'o Nagai and Isuzu Yamada

Tomo'o Nagai and Isuzu Yamada

She also has two otheradult children. One, Momoko (Yoko Katsuragi), is married to the older Tatabe(Jukichi Uno), but does not love him even though he treats her kindly and theyhave a young son. Unfortunately, she’s fallen in love with Tatabe’s cousin, Akaboshi(Yuji Odaka), a two-faced womaniser who laughs at her love letters behind herback. (After he tears one up and throws it in the wastepaper basket, we see hissecretary taping it back together so she can read it).

Urako’s other daughteris Harue (Sanae Nakahara), who dislikes Ginko and wants her brother, Gyo, todump her and date her friend, Shinako (Shinako Mine) instead. However, when hetakes them both to a hot spring inn for a treat, he gets chatting to the barmaid,Yuriko (Misako Watanabe), and when she casually mentions being troubled byathlete’s foot, he jumps behind the bar, removes her socks and smears her toeswith a remedy he happens to have handy, kick-starting a love affair…

This Nikkatsuproduction was based on a 1957 novel entitled Shiki no engi (‘The Four Seasons of Acting/Performance’) by FumioNiwa (1904-2005), whose work also provided the basis for Women of Tokyo (1939), TheBeloved Image (1960) and Four Sisters(1962) among other films. Like many films by director Ko Nakahira, it takes apretty dim view of human nature on the whole, although in this case some of thecharacters are quite sympathetic despite the amount of adultery going on. Inany case, it’s clear that we’re a long way from Ozu and the world of Tokyo Story here, and perhaps that’spartly the point. There’s no genial Chishu Ryu-type father figure in this film,nor any father figure at all for that matter. The screenplay was written by theintriguing if not very prolific Keiji Hasebe, also known for his collaborationswith Shohei Imamura, so new-wavers like him and Nakahira were likely reactingagainst the cosier domestic dramas of Ozu and others. In fact, the ending pilescoincidence on top of coincidence in a way that strongly suggests that Nakahiraand Hasebe were taking the piss.

If you can accept thefilm’s (possibly deliberate) absurdities, there’s much to enjoy, with IsuzuYamada and Yoko Katsuragi taking the acting honours among a strong cast. There’salso an effective score by Toshiro Mayuzumi, albeit one of his moreconventional efforts.

Thanks to A.K.

September 21, 2025

Okuman choja / 億万長者 (‘Billionaire’, 1954)

Isao Kimura

Isao Kimura

Karoku (Isao Kimura) is a tax collector so self-effacing he barelyexists, so it’s easy for the people he’s supposed to collect from to send himaway empty-handed. These include an unemployed photographer, Juji (Kinzo Shin),and his wife (Toyo Takahashi), who have 18 children and a lodger, Sute (YoshikoKuga). Like Karoku, Sute is an orphan who lost her parents to the atom bomb.She believes that the only way to protect peace is for Japan to have its own nuclearweapons and is now devoting all her energy to making them herself.

Karuko is attracted tohis boss’s liberated daughter, Asako (Sachiko Hidari), who works in the sameoffice, and she inspires him to become more aggressive in his collecting, butthis only leads to him being bribed rather than paid. Realising the extent ofcorruption in the tax business, Karuko is persuaded by scheming geisha Hanakuma(Isuzu Yamada) into keeping a record of all the tax evaders. He intends to usethis to expose corrupt politicians like Ebizo (Yunosuke Ito), but she has herown ideas…

This Shintoho releasewas produced by the Young Actors' Club (later known as Gekidan Seihai), whichhad been founded in 1952 and also produced Satsuo Yamamoto’s Hi no hate the same year. According toJapanese Wikipedia,

Isao Kimura, the lead actor,actually lost his family in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Itwas Kimura who also appointed Kon Ichikawa as director.

The film was originally intendedto be a film adaptation of Marcel Pagnol's play Topaz, starring JunkichiOrimoto, Kobo Abe was initially tasked with writing the screenplay, and had alreadycompleted a first draft. However, due to differences with Ichikawa, who hadbeen appointed director, Abe's abstract script was not adopted. Ichikawa'swife, Natto Wada, quicklycompleted the script, and [cartoonist] Taizo Yokoyama andothers contributed their opinions and ideas to the final screenplay, and arecredited as scriptwriters…

This film does not have adirector's name credit. Initially, it was to be distributed by Shochiku, but,after many twists and turns, it was eventually distributed by Shintoho.However, the producers agreed to cut the final scene, depicting the explosionof the atomic bomb, a blend of reality and hallucination, without Ichikawa'sconsent. This led Ichikawa to protest and refuse to have his name credited asdirector... Ichikawa later testified that the reasons for his removal from thecredits were that the Young Actors' Club, the producers, had begun productionwithout completing fundraising and were enthusiastic about it, and that it wasIchikawa's first independent production job and he had proceeded with filmingwithout understanding the circumstances.

However, the version Isaw does have a credit for Ichikawa as director, so I’m uncertain whether theWikipedia article is incorrect or the credit was added to later prints. It’sperhaps also worth noting that, though many sources credit Ichikawa as ascreenwriter, the film itself does not.

Anyway, given thecircumstances in which it was made, it’s perhaps not too surprising that theresultant film is a messy affair, albeit quite an enjoyable one with sterlingwork all around from an excellent cast. Though it’s a wacky satirical comedy inthe vein of other Ichikawa films such as Pu-san(1953) and The Crowded Train (1957),it gets surprisingly dark in places and the underlying message to Japanesecinemagoers in 1954 seems to have been that the post-war problems ofover-population, unemployment, poverty, corruption and atomic weapons meantthat they were all screwed.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English susbtitles)

September 17, 2025

Asakusa kurenai dan / 浅草紅団 / (‘The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa’, 1952)

Machiko Kyo

Machiko Kyo

Maki (Nobuko Otowa) is a dancer at theAsakusa Follies, Ryuko (Machiko Kyo) isa kabuki actress and quick-change artist who was adopted by local gang bossNakane (Joji Oka) when she was a child. Maki is in debt to Nakane, who hasdesigns on her and ordered his men to beat up her boyfriend, Shimakichi (JunNegami), and scare him away from Asakusa. However, Shimakichi injured one ofNakane’s henchmen and escaped before disappearing for a year. Now he’s back insearch of Maki, but Nakane has not forgotten about him and wants revenge, so hetricks Ryuko into luring Shimakichi into a trap…

This Daiei production was supposedly based on Yasunari Kawabata’s1930 novel of the same name, a fine English translation of which was publishedby the University of California Press in 2005 under the title The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa. However,the only thing this film has in common with the novel is that it concerns thecriminal underworld of Asakusa, a pleasure district of Tokyo which was twicedestroyed – first by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, later by Americanbombs. Kawabata’s novel is a largely plotless and uncharacteristicallymodernist work consisting of a series of vignettes about the petty thieves andprostitutes who haunted the back alleys of Asakusa and kept an eye for out foreach other. Not only is there no gang boss like Nakane, but none of thecharacters from the book appear in the film and the setting has been updated tothe post-war era. While the nature of Kawabata’s novel would have made itdifficult to adapt for the screen, it’s disappointing that screenwriterMasashige Narusawa failed to come up with a better story than the cornymelodrama which unfolds here, especially considering the fact that he was responsiblefor many fine scripts, including a number for Mizoguchi.

The other reason I found this film something of a let-down is thatit was directed by Seiji Hisamatsu, whose later works Five Sisters (1954) and Policeman’sDiary (1955) I greatly enjoyed. On a more positive note, it does offer afun role for Machiko Kyo, who gets to appear in a number of different guises,as she would also later do in The Hole(1957) and Black Lizard (1962). Watchingthe scene in which Ryuko pretends to be a country bumpkin, I even found myselfwondering who the strangely familiar-looking actress was before realising itwas Kyo.

Otherwise, Joji Oka is a rather hammy bad guy and Jun Negami a decentenough hero, while a young Nobuko Otowa gets to sing the theme song, dance andshow off what Daiei touted as her ‘million dollar dimples’. Perhaps it waspartly being reduced to a pair of dimples that led her to quit Daiei the yearthis film was released and pursue largely unglamorous roles from then on.

Presumably, the film proved popular as Daiei followed it with Asakusa monogatari (‘Asakusa Story’) thefollowing year, Asakusa no yoru(‘Asakusa at Night’) in 1954 and Asakusano hi (‘Lights of Asakusa’) in 1956, although I believe that each featuredan entirely separate story.

There had actually been an earlier film of the same title, againsupposedly based on Kawabata’s book, back in 1930. It appeared before Kawabatahad even finished the novel, which was being published in instalments in the Tokyo Asahi newspaper. Unfortunately,the 1930 film appears not to have survived.

Thanksto A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

September 12, 2025

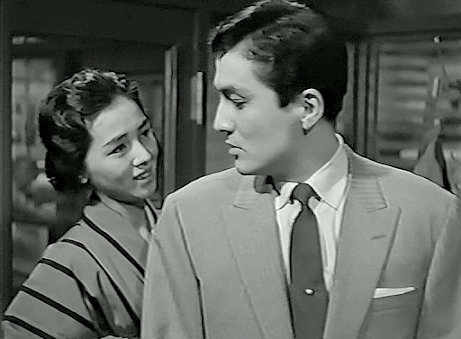

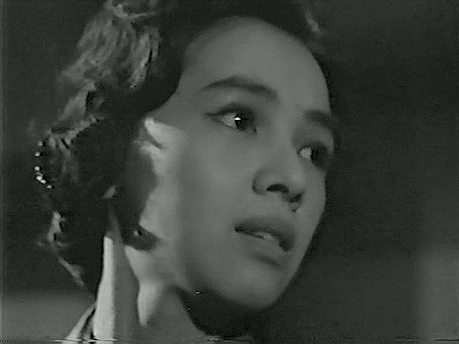

Escape at Dawn / 暁の脱走 / Akatsuki no dasso (1950)

Yoshiko Yamaguchi

Yoshiko Yamaguchi

1945. Harumi (Yoshiko Yamaguchi) is a singer in a troupe of femaleentertainers sent to Manchuria to help the Japanese soldiers forget about theirprobable imminent deaths. Unfortunately, she quickly attracts the attention of overbearingLieutenant Narita (Eitaro Ozawa) and is about to be raped by him when PrivateFirst Class Mikami (Ryo Ikebe) knocks on the door to deliver a trivial telegramto Narita, allowing Harumi to escape. Harumi and Mikami fall in love, but, when he's wounded in battle, circumstances lead to them being captured together by the Chinese. Mikami istreated with nothing but kindness by his captors, but he’s been completelybrainwashed by the Japanese military propaganda machine into thinking that it’sbetter to die than be taken prisoner…

Produced by Shintoho,the company founded by those who split from Toho after the studio’s big labourdispute of 1947, Escape at Dawn wasnevertheless distributed by Toho. Like director Senkichi Taniguchi’s previousfilm, Jakoman and Tetsu, it was alsoproduced by Tomoyuki Tanaka and co-written by Akira Kurosawa. In this case, thesource was a 1947 novel by Taijiro Tamiya (1911-83) entitled Shunpu den (‘The Story of a Prostitute’,not available in English). Tamiya had served in Manchuria during the war (ashad Taniguchi) and also written Nikutaino mon (‘The Gate of Flesh’), first filmed in 1948 by Masahiro Makino andlater by Seijin Suzuki, Hideo Gosha and others.

Although Tamiya is saidto have created the character of Harumi with Yoshiko (later Shirley) Yamaguchi in mind, inthe novel she was a Korean prostitute (or ‘comfort woman’), while it’s madevery clear in the film that she is not a prostitute, and she has also becomeJapanese. Apparently, the original version of the screenplay was faithful tothe novel on these points, but the content of Japanese films was still beingcontrolled by the occupying Americans, who insisted that changes be made. It’shard to see how such whitewashing benefitted the Americans, so their decisionwas presumably just a case of them imposing their own cultural nanny-stateideas of the time about the depiction of ‘immorality’ on screen. An unfortunateknock-on effect was that Harumi’s behaviour in the way she throws herself atMikami and won’t take no for an answer now appeared extremely odd coming from aJapanese singer rather than a Korean prostitute. According to Stuart GalbraithIV in his book The Emperor and The Wolf,Kurosawa eventually got fed up with the requests for endless rewrites and leftTaniguchi to it. He also states that,

…long preproduction,expensive exterior sets, and tangled red tape to secure permission for use ofmilitary hardware for filming (machine guns, etc) made it the most expensiveJapanese feature to that point.

I’ve read elsewherethat it was also the first post-war Japanese film to feature scenes of Japanese soldierson the frontlines. In any case, while it’s certainly a compromised vision, thefilm is at least very well-made and often technically impressive, with cinematographerAkira Mimura winning a Mainichi Film Concours award for his efforts. On theother hand, the essentially simple story of a predictably doomed romance feelsoverstretched at almost two hours. As Lieutenant Narita and his men are stationed in the desert, thefilm is very much like a Japanese Foreign Legion movie, and memories of MarleneDietrich and Gary Cooper in Morocco(1930) are often brought to mind. There are some surprisingly sensual scenes betweenstars Yoshiko Yamaguchi and Ryo Ikebe – at one point, she bites his hand hardenough to draw blood, then sucks the wound, which he seems to enjoy. This wouldhave been considered strong stuff in Japan in 1950 and probably helped at thebox office.

Seijun Suzuki directed a more faithful version of the originalnovel in 1965.

Bonus trivia:

Setsuko Wakayama, whoplays one of Harumi’s colleagues, had married director Senkichi Taniguchi in1949, but they divorced in 1956 when he had an affair with actress Kaoru Yachigusa.This adultery scandal harmed Taniguchi’s career greatly – after directing anaverage of three films a year until 1957, he was subsequently out of work forover two years. When he did return to directing, the quality of the material hewas offered was significantly lower than it had been before the scandal.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

September 7, 2025

Jakoman and Tetsu / ジャコ万と鉄 (1949)

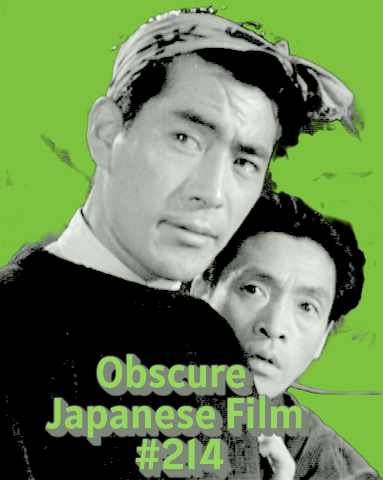

Toshiro Mifune and Kamatari Fujiwara

Toshiro Mifune and Kamatari Fujiwara

Kyubei (Eitaro Shindo, better known as Sansho the Bailiff) has a herring-fishing business in Hokkaido andis anticipating the annual arrival of the fish when his son, Tetsu (ToshiroMifune) – presumed missing in the war – unexpectedly turns up. Tetsu issurprised to find that one of the fishermen employed by his father just liesaround all day drinking saké and refusing to work. The man in question is Jakoman(Ryunosuke Tsukigata), an aggressive individual with an eye-patch whom everyoneis afraid of and who has a beef with Kyubei because Kyubei stole his boat toescape from Sakhalin island when the Japanese were chased out by the Russiansat the end of the war.

Meanwhile, a woman named Yuki (Yuriko Hamada) turns up in searchof Jakoman, and it emerges that she’s in love with him despite the fact that hewants nothing to do with her and treats her roughly. In the midst of all thispersonal drama, the herring finally appear just as the men call a strike due tolow pay…

This Toho production* was based on a 1947 novel entitled Nishin ryoba (‘Herring Fishing Grounds’)by Tokuzo Kajino (1901-84, sometimes incorrectly listed as ‘Keizo Kajino’ or‘Shinzo Kajino’). The screenplay was co-written by the director, SenkichiTaniguchi, and Akira Kurosawa, with whom Taniguchi frequently collaborated duringthis stage in their careers, and its full of characteristic Kurosawa touches. Onesuch is when Kyubei’s son-in-law (Kurosawa favourite Kamatari Fujiwara), anapparently slow-witted clerk given to hiccups and sneezing, plays the shakuhachi (bamboo flute) and moveseveryone to tears, instantly clearing up the mystery of what his wife (NijikoKiyokawa) sees in him. Indeed, the script seems to have been largely the workof Kurosawa, with Taniguchi making some changes when he came aboard asdirector, and Kurosawa apparently brought the characters of Jakoman and Tetsuto the fore for the film, whereas the source novel had Kyubei as its mainprotagonist. Concerning Taniguchi, it’shard to take him very seriously as a director given the hokum that he made inthe final years of his career, while the fact that so many of his other films are basicallyinaccessible means that he’s likely to be forever regarded as a footnote toKurosawa (who was said to have done much of the editing on Taniguchi’s earlyfilms).

Mifune – who has to perform a spectacularly weird song and dancewhich I bet embarrassed him – looks great and is effortlessly likeable asTetsu, while Ryunosuke Tsukigata is almost too convincing as the villainousJakoman, his one eye glinting with concentrated malevolence. Tsukigata hadpreviously played two of the opponents in Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata films and has a staggering 499 credits on theJapanese Movie Database. The female lead, Yuriko Hamada, also makes a strongimpression even if her feisty character is tamed at the end. (Hamada’s fateremains a mystery – she made her final film in 1957 and nobody seems to knowwhat happened to her after that.) Excellent use of locations and a fine scoreby Godzilla composer Akira Ifukubealso help to make this an enjoyable watch. The main flaw of the film is that itlacks subtlety in the way it puts across its rather obvious moral message.

In regard to Kinji Fukasaku’s 1964 remake, while it was a goodidea to replace the original film’s subplot of Tetsu falling in love with agirl he sees playing the organ in a Christian church** (played by an almostunrecognisably young Yoshiko Kuga) with one in which he falls in love with thesister of a deceased comrade whose family he visits, in my opinion that was theonly thing that the remake did right. Aside from that, everything that was goodabout the first film has evaporated in Fukasaku’s tedious version, which seemsto have been a vanity project initiated by its star, Ken Takakura. Unfortunately,that’s the one which is available in a very nice limited Blu-Ray from 88 Films.

The original film was abox office success and spawned a sequel entitles Jiruba Tetsu (1950) again starring Mifune, Yuriko Hamada and EitaroShindo and co-written by Kurosawa but directed by Isamu Kosugi and produced byTokyo Eiga.

*Actually, although itwas distributed by Toho and bears the Toho logo at the beginning, the followingtitle card announces the film as a ’49 Years production’. It seems to be theonly film credited thus, something which appears to be a result of the labourdispute that was going on at Toho at the time. Perhaps the strike called by themen in the film was partly a comment on the situation, but though the fishermen settletheir differences with Kyubei, that was sadly not to be the case at the studio.

**According to ‘I LoveJakoman’ on Amazon Japan,

…it was Taniguchi's idea for Tetsu to fall in love with the church girl, andupon hearing it, Akira Kurosawa reportedly remarked, "That stinks."(Taniguchi himself said this at a Taniguchi Film Screening).

Only Kurosawa andTaniguchi are credited with the screenplay for the 1964 remake, but it’sunclear whether either had any involvement in the changes made.

Watched without subtitles

September 3, 2025

Rise, Fair Sun / 朝やけの詩 / Asayake no uta (‘Poem of the Morning Glow’, 1973)

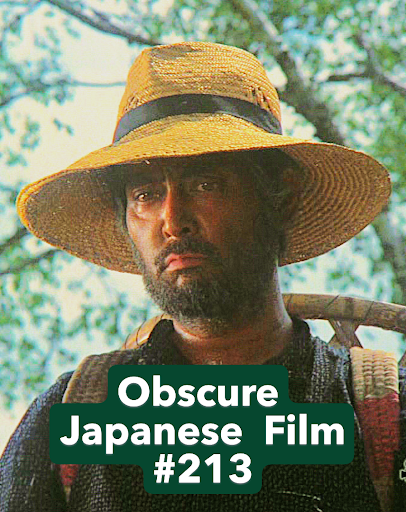

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya Nakadai

The Shinano Plateau,Nagano. Left without a position after Japan’s defeat, former naval officer Sakuzo(Tatsuya Nakadai) is now a comparatively poor but hard-working and extremelyproud farmer with a teenage daughter, Haruko (Keiko Takahashi), and two youngerchildren, all of whom he is raising by himself. His wife, Yaeko (KanekoIwasaki), seems to have been unable to bear the drudgery, has developed a drinkingproblem and left him for an easier life, shacking up with Kamiyama (YosukeKondo). He’s the president of Apollo Tourism, who want all the farmers in thearea to clear out so they can use the land to build a holiday resort. As thefarmers are all in debt to local bigwig Inagi (Shin Saburi), Kamiyama conspireswith him to make them an offer they can’t refuse, but some – like Sakuzo –prove inconveniently stubborn. When land surveyors are sent in, violence breaksout…

Kaneko Iwasaki and Keiko Takahashi

Kaneko Iwasaki and Keiko TakahashiRise,Fair Sunwas a co-production between Toho and Haiyuza, the theatre company to whomNakadai and a number of his fellow cast members (including Kaneko Iwasaki andYosuke Kondo) belonged. The film was directed by Kei Kumai and based on hisoriginal screenplay, co-written with the little-known Akiko Katsura and theslightly better-known Hisashi Yamanouchi, who had worked on three of ShoheiImamura’s early pictures. Like many of Kumai’s films, it has an obviousleft-wing, social conscience theme.

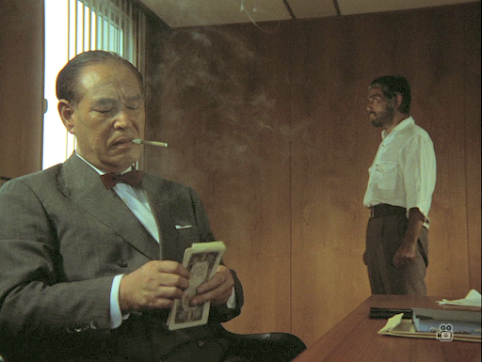

Shin Saburi and Nakadai

Shin Saburi and NakadaiIn the early 1970s,many Japanese feature films returned to using the old academy ratio that thestudios had originally abandoned around 1957, and this film is one example of such. As I understand it, this was mainly done because it was cheaper and thestudios’ profits were diminishing, but I also wonder whether it may have beenrelated to the more TV-friendly nature of the academy ratio as the sale offilms to television after their cinema run was more of a concern by this point.In any case, it’s part of the reason why Rise,Fair Sun has something of a TV miniseries feel to it. However, that’s notto say that the film fails to impress visually – mostly shot on location, itfeatures some beautiful scenery and attractive cinematography by Kozo Okazaki (Goyokin, Inn of Evil) which includes a spectacular shot of Haruko and heryoung lover silhouetted against the sun towards the end. Another plus is the scoreby Kumai’s regular composer, Teizo Matsumura, which is refreshingly free fromthe usual clichés.

The film is generallyvery sympathetic to Sakuzo despite the clear suggestion that his wife has beena victim of domestic violence, an implied additional motivation for herabsence. Like Toshiro Mifune in Redbeard,there’s a scene in which Nakadai appears to forget that he’s not in a samuraimovie and launches a one-man attack on multiple opponents – in this casegrabbing a surveying pole and going into full Sword of Doom mode on the unfortunate surveyors. As if tocompensate for this violent side, he tries to save a bloated cow (by stabbingit!) and, while digging on his land, he discovers an ancient pot from the Jomonpeople (who were believed to have lived in harmony with nature to a remarkabledegree). This instantly turns his farm into a major archaeological site, andwhen a Jomon face sculpture is dug up, he declares it better than anything in theLouvre (which he has apparently visited while in the navy). This unexpectedplot thread is quickly dropped, but – with symbolism not too hard to decipher –we will later see a shot of a bulldozer carelessly running over another pieceof Jomon pottery.

The film marked veteranstar Shin Saburi’s return to the big screen after an absence of 12 years,during which time he had been very active as both an actor and director intelevision. It was his first film opposite Nakadai and there’s a memorableconfrontation scene between the two, who were reunited the following year inSatsuo Yamamoto’s The Family. Nakadaihad known his other co-star, Kaneko Iwasaki, since the very beginning of hisacting career and the two had appeared in a number of films together. Thoughshe has seldom had leading roles in feature films, Iwasaki is the officialrepresentative of Haiyuza at the time of writing and remains a highly respectedstage actor who played the King Lear equivalent in Haiyuza’s 2024 production Dokoku no Ria (‘Lear’s Lament’).

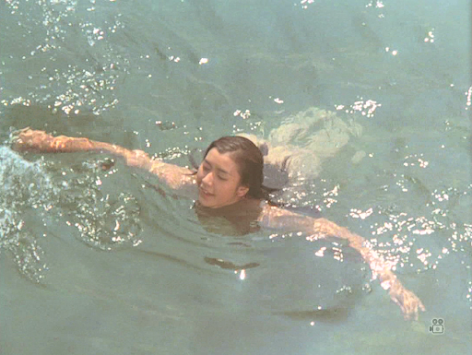

The production of thefilm was overshadowed by the publicity around the nude swimming scene featuringan 18-year-old Keiko Takahashi – then known as Keiko Sekine – who had alreadybeen a popular star for a couple of years at this point. Although the inclusionof such a scene may have been a cynical move by the producers, it wastastefully shot by Kumai, but in any case it was not enough to make Rise, Fair Sun a hit either at the box office or with the critics. Though screened in competition at the Berlin Film Festival, it failed to win anyprizes. This is not too surprising as, despite some good work in a number ofdepartments, it’s basically a noble effort which doesn’t quite gel – mainly, Ithink, due to the flawed script and somehow unconvincing characters. In my view,stories of this type often work better with a more Ken Loach-type approach, inwhich the use of improvisation by a cast of mainly non-professionals can be more effective.

The Berkeley Art Museumand Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Film Library in Californiaa has a 35mm print of this film with English subtitles

Thanks to A.K.

August 29, 2025

Ten no yugao / 天の夕顔 (‘A Moonflower in Heaven,’ 1948)

Mieko Takamine

Mieko Takamine

Toyohiko Fujikawa

Toyohiko FujikawaTatsunoguchi (Toyohiko Fujikawa) is a recluse who lives in a huton a snowy mountain and shoots rabbits for his dinner. One day when outhunting, he notices a man (Haruo Tanaka) lying in the snow. The man is stillalive and asks Tatsunoguchi to leave him there, but he takes him to his hut andnurses him back to health. It emerges that the man had wanted to die due to a loveaffair that went wrong, so Tatsunoguchi begins to tell him his own story of howhe ended up living in such isolation.

As a student, every Friday Tatsunoguchi had passed a young woman,Akiko (Mieko Takamine), on his way to university and gradually fallen in lovewith her. However, the encounters suddenly ceased and, when he did finally runinto her again three years later, she had already acquired both a husband and an infant son, although her marriage was a failure. Akiko reciprocated Tatsunoguchi’s feelings,so their love continued to grow, resulting in an on-and-off relationship thatcould only ever be platonic dragging on for years and leading to Tatsunoguchi's eventualself-exile to the mountain…

This Shintoho production was based on a 1938 novel of the samename by Yoichi Nakagawa (1897-1994) and is the only film adaptation of his workto date. According to Japanese Wikipedia, the novel ‘garneredhigh praise in Western Europe as a masterpiece of romantic literature, comparable to Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. After the war, it was translatedinto six languages, including English, French, German, and Chinese, and washighly praised by Albert Camus.’ We also learn thatNakagawa got the story upon which he based his book from a masseur namedKozaburo Fujiki, who greatly resented the fact that Nakagawa refused to givehim any credit. A feud between the two men lasted for decades, culminating inthe self-publication of a 1976 book by Fujiki with the splendid title The Great Achievement of Shattering the Masterpiece Ten no yugao - A Guide for Reading Novels Carefully andwith Taste.

This literary feud isarguably more entertaining than the film itself, which is an extremely maudlinpiece of work, an aspect emphasized by the keening violin featuredexcessively throughout composer FumioHayasaka’s score. Director Yutaka Abe had already made around 60 films at thispoint, and went on to make The MakiokaSisters (1950) and Confession(1956). He certainly does a competent job, but the material is so old-fashionedand sentimental that it has dated very badly indeed and is at times evenlaughable today - the animated firework near the end being an especially corny touch.

Leading lady MiekoTakamine will be familiar to many readers, but who, you may well wonder, was herco-star, Toyohiko Fujikawa? Well, he seems to havebeen born in 1924 and has just two other credits, both in Daiei movies from1950. According to @Shimo_x2on x.com, he ‘was not originally an actor but a young president of aconstruction company. It seems he also invested in this film, making hisappearance in the movie something of a hobby.’ In any case, he gives a slightlystolid but perfectly acceptable performance and certainly looks the part of aleading man.

This film appears to lack an official English title, but is sometimeslisted as ‘The Beauty of the Evening Sky.’ However, the first kanji can beinterpreted as ‘heaven’ as well as ‘sky’ and, while夕on its own means ‘evening’ and 顔 can mean ‘face’ (but not ‘beauty’), the final twotogether mean ‘moonflower’, and there is in fact a scene in which MiekoTakamine admires a moonflower (ipomoeaalba), which bloom at dusk and last only for one night. The Englishtranslation of the book by Akira Ota published by The Hokuseido Press in 1949is also titled A Moonflower in Heaven.The cover art is by Jean Cocteau.

Watched with dodgy subtitles.

August 26, 2025

Izu no odoriko / 伊豆の踊子 (‘The Dancing Girl of Izu’, 1954)

Hibari Misora

Hibari Misora

ThisShochiku production was the second film version of a famous short story byfuture Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972). First published in1926, it's a semi-autobiographical piece based on a solitary walking trip hetook as a student around the Izu Peninsula in the year 1918. Attracted to ayoung dancer who is part of a small group of travelling entertainers, thenarrator (named Mizuhara in the film) contrives to fall in with them. The othersare Eikichi, a man of 23 who is the leader; his 18-year-old wife Chiyoko; hermother; and Chiyoko’s 16-year-old sister, Yuriko. The dancer, named Kaoru, is Chiyoko’s youngestsister. Although disconcerted to find that she is only 13 (he had judged her tobe 15-16*), he finds himself deeply moved at the group’s friendliness towardshim, and this greatly helps to mitigate his low self-esteem.

Whilethe story is often characterised as one of unrequited youthful love, there’smore to it than that. Like Kawabata, the narrator/Mizuhara is an orphan with noclose family left alive, and Kawabata is said to have been concerned as a youngman that this fact may in some way warp his personality. Despite the extremelylow status of travelling entertainers in Japanese society at the time, thefamily in the story are not unhappy and enjoy a warm relationship with oneanother. It’s clear that the narrator is pathetically grateful to be accepted –almost adopted – by these outcasts, and this aspect of the work is equally asimportant as the theme of young love.

Evenin its unabridged form, Kawabata’s story is not really long enough to sustain afeature-length film, so screenwriter Akira Fushimi expanded it, mainly by giving the family ofentertainers a more detailed backstory, introducing a rival for Kaoru’s loveand adding a minor sub-plot about a young boy pursuing Mizuhara from villageto village to return some money he had dropped. Incidentally, it was Fushimiwho had also written the screenplay for the first adaptation, a silent filmmade by Heinosuke Gosho in 1933. However, for this one he wrote a fresh scriptwith a number of differences, the most notable being that the character ofEikichi is far more sympathetic in the second version, in which he is played byAkihiko Katayama. This is more faithful to Kawabata.

Thesilent version had starred a 22-year-old Kinuyo Tanaka alongside the26-year-old Den Ohinata, whereas this one stars 16-year-old Hibari Misora asKaoru and 19-year-old Akira Ishihama as Mizuhara. Misora was best-known for hersinging ability, but gets surprisingly few opportunities to sing here, whileIshihama will be familiar to many as the young samurai forced to commit seppuku with a bamboo sword in Harakiri (1962). Although these twoactors are the right age for their characters, I felt that their actingabilities were a little too limited to really put across their feelings asdescribed by Kawabata, but director Yoshitaro Nomura is also partly to blamefor this. Compare the final scene on the boat with what Kawabata had writtenand you’ll probably see what I mean. Here’s what Kawabata wrote (as translatedby J. Martin Holman):

I lay down, using my bag as apillow. My head felt empty, and I had no sense of time. My tears spilled onto my bag. My cheekswere so cold I turned my bag over. There was a boy lying next to me. He was theson of a factory owner in Kawazu and was on his way to Tokyo to prepare toenter school. The sight of me in my First Upper School cap seemed to elicit hisgoodwill.

After we talked for a while, heasked, "Have you had a death in your family?"

"No, I just leftsomeone."

I spoke meekly: I did not mindthat he had seen me crying. I was not thinking about anything. I simply felt asthough I were sleeping quietly, soothed and contented.

I was not aware that darkness hadsettled on the ocean, but now lights glimmered on the shores of Ajiro andAtami. My skin was chilled and my stomach empty. The boy took out some sushiwrapped in bamboo leaves. I ate his food, forgetting it belonged to someoneelse. Then I nestled inside his school coat. I felt a lovely hollow sensation,as if I could accept any sort of kindness and it would be only right. […]

The lamp in the cabin went out.The smell of the tide and the fresh fish loaded in the hold grew stronger. In thedarkness, warmed by the boy beside me, I let my tears flow unrestrained. Myhead had become clear water, dripping away drop by drop. It was a sweet, pleasantfeeling, as though nothing would remain.

Butin the film, Ishihama can barely manage a single tear and Nomura decides to endit with a shot of Misora staring blankly at the water, followed by a shot of asingle geta (wooden sandal) floatingoff. Personally, I felt that Nomura had rather missed the point of the endingand also not shot what he did as effectively as he could have – a shame, as otherparts of the film are a good deal more impressive.

Afterthe success of his 1958 film Stakeout,Yoshitaro Nomura became best-known for his intelligent and twisty crime dramas,often based on Seicho Matsumoto stories, and films from this earlier stage inhis career are not easy to see. The nature of the story meant that the bulk ofit had to be shot on location, and this is something that Nomura seemed torelish. Despite his odd lack of focus (for the most part) on the emotions ofthe two main characters and the performances of the two leads, he was atalented filmmaker and this is most obvious in a sequence which occurs around21 minutes in, contains no dialogue and lasts for just under three minutes. Itsimply features Mizuhara walking by himself during a heavy rain shower andpausing to take shelter in a doorway, through which he watches a baby cryingalone until a boy (presumably the baby’s older brother) runs up and stares athim, at which point he hurries on. There’s a sense that even the crying baby isbetter off than Mizuhara because at least it has a big brother to look afterit. This beautiful sequence does nothing to advance the plot but expressesMizuhara’s loneliness perfectly without even requiring Ishihama to do much inthe way of acting. Most of the film and this scene in particular are alsohelped by Chuji Kinoshita’s restrained score – one of his better ones, with theexception of his use of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ at the end, which can’t help but feelcorny. Anyway, despite my quibbles, this film is well worth seeking out and quite likely the best film version of the story to date.

*Othersources may give different ages depending on which age system is used, and thetwo translations of the story intoEnglish do not agree. The first, by Edward Seidensticker, appeared in 1954, wasslightly abridged, and described Kaoru as being dressed and made-up to appear15 or 16, but turning out to be only 13. The second translation, by J. MartinHolman, appeared in 1997, was unabridged, and described Kaoru as looking 17 or18 but actually being 14. The discrepancy is due to the fact that Seidenstickerused the standard system of counting age in the West, whereas Holman used thetraditional Japanese system, which considered a person to be one year old atbirth and for their age to increase by a year not on their birthday, but at theturning of the New Year. This system is no longer used in Japan.

Thanks to A.K.

August 22, 2025

Arijigoku sakusen / 蟻地獄作戦 / (‘Operation Antlion’, 1964)

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya Nakadai

This Toho production was the fourth entry in their ‘Sakusen’(‘Operation’) series, which attempted to emulate the style of Kihachi Okamoto’s1959 hit Desperado Outpost and itssequel (in fact, it’s sometimes considered the sixth film in the Desperado Outpost series). These filmshad brought a new cynicism and humour to the war action genre in Japan andfound favour with males of the younger generation, for whom the more po-facedwar films were often a turn-off.

This one stars Tatsuya Nakadai – who had actually been offered thelead in Desperado Outpost but beenobliged to turn it down due to his commitment to The Human Condition. This turned out to be a stroke of luck forMakoto Sato, who was cast in his place and went on to star in all of thefollow-ups. However, in this film he plays second banana to Nakadai, apparentlybecause Toho wanted to try increasing the audience numbers by giving the leadto an actor with a lot of female fans.

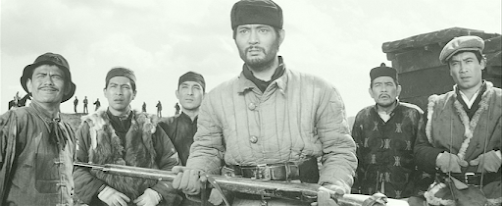

L-R: Natsuki, Hirata, Sato, TN, Sakai,

L-R: Natsuki, Hirata, Sato, TN, Sakai,

Nakadai plays Lt. Isshiki, an insubordinate junior officerassigned with a suicide mission to blow up a bridge somewhere in China duringthe final months of the war. He’s given a team of five other insubordinatetypes, several of whom are released from the stockade for the purpose. Theother men are played by Makoto Sato, Yosuke Natsuki, Sachio Sakai, AkihikoHirata (the one-eyed scientist in the original Godzilla) and Tadao Nakamaru. Naturally, this dirty half-dozen encountera variety of dangers on their way to the bridge and mow down a large number ofunfortunate Chinese National Revolutionary Army fighters in the process. Ofcourse, it’s one thing watching soldiers of the Allied Forces machine-gunningNazis and quite another when it’s Japanese soldiers doing it to the Chinese,which makes this film and its ilk a little problematic. The filmmakers throw ina couple of ‘good’ Chinese characters, but neither are convincing. One is anapparently cowardly villager played by Kan Yanagiya who turns out to be aresistance fighter, while the other is a grimy-faced ‘boy’ who looks exactlylike a young woman and turns out to be (surprise, surprise) a young woman.Played by Kumi Mizuno, she falls in love with one of the Japanese soldiersafter he gives her a rice ball. Still, if its gritty realism you’re after,you’re watching the wrong film as this is strictly entertainment and, to befair, it succeeds pretty well on that level even if much of the humour was toobroad for my taste.

The film moves along at a good pace and is very well staged andshot by director Takashi Tsuboshima and his cinematographer Fukuzo Koizumi (whoalso shot Kurosawa’s Sanjuro).Tsuboshima had worked as an assistant to Jun Fukuda, who was best-known for hismonster movies, and he was probably not the best with actors – allowing toomany of the supporting cast to go way over the top here – but clearly had agreat deal of technical skill. Although his output was largely routine, helater made the interesting Bonds of Love(1969).

Nakadai looks like he’s enjoying himself in a more straightforwardaction role than he usually played, and does plenty of horse-riding andshooting, but there’s nothing to stretch him here. Although the movie pre-datesThe Dirty Dozen (1967), the influenceof English-language war films (especially TheGuns of Navarone) and westerns is obvious. Toho’s DVD release boastsperfect picture quality and the film is not too difficult to follow evenwithout subtitles as the plot mostly consists of men-on-a-mission clichés anyway.

A note on the title:

As far as I’m aware, the film has not beendistributed in any English-speaking countries and has no official Englishtitle. IMDb and some other sites list it as‘Jigoku sakusen’, but that title gives only the last four kanji in romanji. The first kanji, 蟻, means ‘ant’, while the second and third togethermean ‘hell’ and the final two (‘sakusen’) in combination can mean ‘tactics’, ‘strategy’ or ‘military operation’. Letterboxd lists the film as ‘Ant Hell War’. However, although a literaltranslation of the first three kanji gives ‘ant hell’, it’s actually the Japanese name for ‘antlion’. Wikipedia offers the followinginformation:

The antlions are a group of about 2,000 species of insect in th neuropteran family Myrmeleontidae. They are known for the predatory habits of their larvae, which mostly dig pits to trap passing ants or other prey.

In Japan, both the insect and its pit-traps are popularly known as Arijigoku (蟻地獄; lit. "Ant Hell"). This term has since become a stock colloquialism for any "inescapable" trap, whether literal or metaphorical (e.g. an unpleasant social obligation).

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antli...

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antli...

DVD at Amazon Japan (no subtitles)