M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 5

April 6, 2025

Structure of Hate / 黒い画集 第二話 寒流 / Kuroi gashu dainibu: Kanryu (1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #178

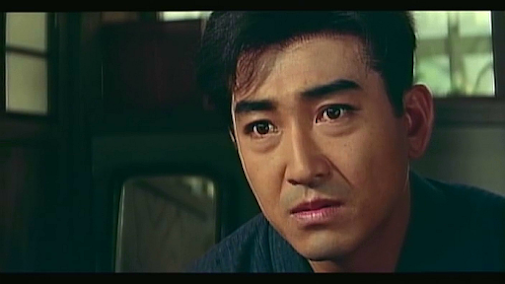

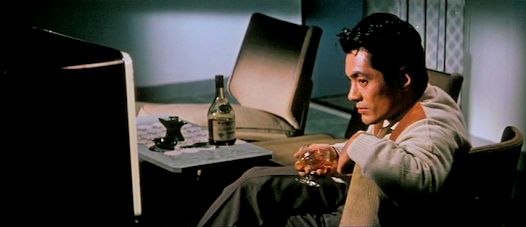

Ryo Ikebe

Ryo IkebeOkino (Ryo Ikebe) is ahard-working Tokyo bank employee who is entrusted with a promotion to manager ofthe Ikebukuro branch by his boss, Kuwayama (Akihiko Hirata). However, Okino isdisliked by his wife (Michiko Araki) and two children because he’s so focusedon his work that he largely ignores them. Soon after starting his new job, he’sapproached for a bank loan by restaurant owner Nami (Michiyo Aratama) and amutual attraction soon leads to an affair. As such a relationship with acustomer of the bank could cost Okino his job, he must be especially careful tokeep it a secret – something that becomes increasingly difficult when Kuwayamameets Nami and decides to pursue her himself. Then Okino begins to wonder ifNami has just been using him for her financial benefit…

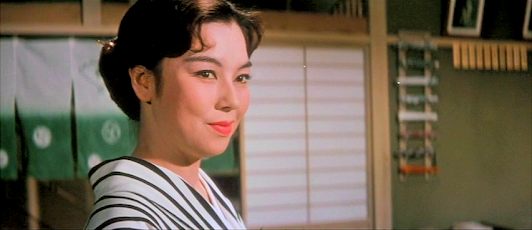

Michiyo Aratama

Michiyo AratamaThe Japanese title ofthis Toho production translates as ‘Black Art Book Episode 2: Cold Current’ as‘Cold Current’ was the title of Seicho Matsumoto’s story first serialised inthe Weekly Asahi in 1959 before beingincluded in the collection Black Art Book2, published later that year.* Harenchi Gakuen helpfully explains onFilmarks.com that, ‘The cold current refers to the side streams and those whohave been demoted.’ This makes perfect sense as Okino certainly finds himselfsidelined in this film version by screenwriter Tokuhei Wakao and director HideoSuzuki. Unfortunately, the original story is not available in English, butapparently the ending was changed significantly. It’s a little different fromyour typical Seicho Matsumoto tale – there’s not even a murder – and the plotwent off in directions I failed to anticipate, but did enjoy, culminating in ahighly unusual ending in which we are deliberately kept in the dark aboutexactly what happened.

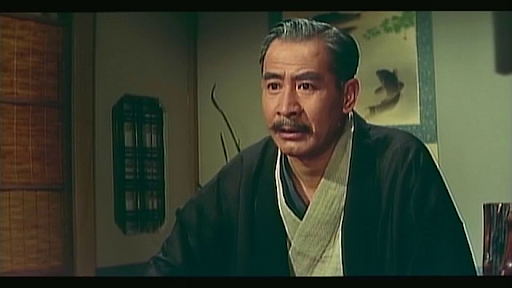

Akihiko Hirata

Akihiko HirataIt’s a refreshinglyunsentimental film which takes a pretty dim view of human nature. Having saidthat, the two main characters are not entirely despicable. It’s common in Japanfor men to put work before family as Okino does here, and although Nami is thebusiness-minded, pragmatic type, she’s put in a difficult position withwhich it’s hard not to sympathise, while it’s also clear that their relationshipbegins to trouble her conscience. In this role, the underrated Michiyo Aratamadelivers the film’s best performance and it’s good to see her show what shecould do when given a meatier part than the typical ‘nice girl’ roles she’sbetter-known for in films such as TheHuman Condition.

Jun Hamamura

Jun Hamamura Seiji Miyaguchi

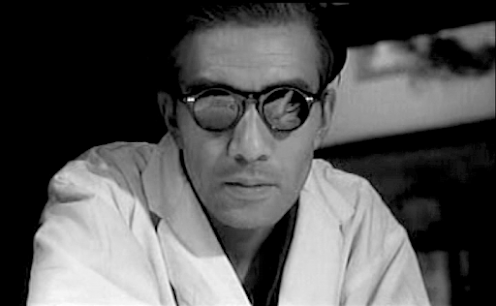

Seiji MiyaguchiThe film has somewonderful cameos by familiar faces such as Jun Hamamura as a doctor who lookslike he could use some of his own medicine, Seiji Miyaguchi as a privatedetective who looks like he hasn’t had a client for years, Tetsuro Tanba as ayakuza boss and, best of all, Takashi Shimura as a shark-like banking bigwigwho exudes an aura of self-confidence and power and is appropriately trailedeverywhere by his silent, pilot-fish-like mistress (Machiko Kitagawa).

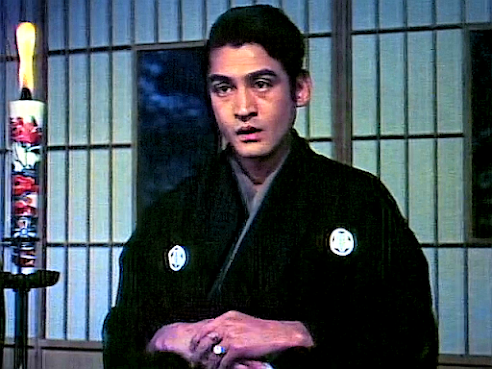

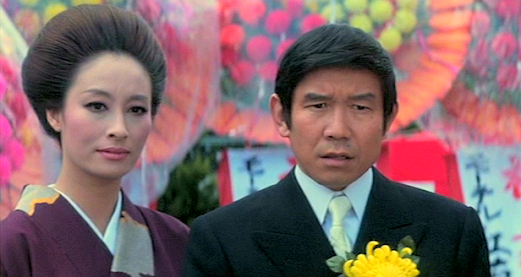

Tetsuro Tanba and friends

Tetsuro Tanba and friends Takashi Shimura

Takashi ShimuraThis is the only filmI’ve seen so far by director Hideo Suzuki (1916-2002), who worked as a contractdirector first for Daiei (1947-52), then Shintoho (1953) and finally Toho(1954-67) before finishing his career in TV. Although he is said to have had alimited amount of choice in the films he was assigned to direct and he worked in avariety of genres, he is apparently highly regarded by some for his thrillersand suspense movies, and on the evidence of Structureof Hate, I, for one, am keen to see more, especially as there’s more tothis film than mere suspense. It’s also a portrait of a sick society in whichpeople have become foolishly obsessed with position and material wealth whileforgetting what’s really important in life.

Michiyo Aratama

Michiyo Aratama*Toho had made Black Art Book: An Employee’s Confession aka The Lost Alibi the previous year and Black Art Book: A Certain Disaster aka Death on the Mountain earlier in 1961. Structure of Hate was the final entry inthe series.

Thanks to A.K.

March 30, 2025

Five Sisters / 女の暦 / Onna no koyomi (‘A Woman’s Calendar/Almanac’, 1954)

Obscure Japanese Film #177

Kyoko Kagawa

Kyoko Kagawa Yoko Sugi

Yoko SugiTheir parents now deceased, two adult sisters now live together intheir old family home on an island, Shodoshima, in the south of Japan. Theyoungest of five sisters, they are Kuniko (Yoko Sugi), aschoolteacher who is reluctant to get married, and Mie (Kyoko Kagawa), who isaround nine years younger and has a very different attitude – unbeknownst toKuniko, she’s in love with a burly pig farmer (Gen Funabashi) and wants tomarry him.

Gen Funabashi, Kyoko Kagawa and friend

Gen Funabashi, Kyoko Kagawa and friend

As the anniversary oftheir father’s passing is approaching, Kuniko and Mie decide that it’s time tohave a family get-together, so they invite their three elder sisters to visit.The most senior, Michi (Kinuyo Tanaka), lives in Hiroshima and has fivechildren of her own and a lazy, pachinko-addicted husband (Hisao Toake), while Takako(Yukiko Todoroki), who lives in Tokyo, is married to a man who’s in prison forgetting caught up in a demonstration. Finally, there’s Kayano (Ranko Hanai),who lives in Osaka and is unhappily married to Sugie (Masao Mishima), who’s alwaysunfavourably comparing her to his first wife. Will the examples of the threevisiting sisters deter Mie from marriage as they have in Kuniko’s case? Or hasshe been scared into thinking she must get married in order not to end up likeOfuku (Eiko Miyoshi), a crazy old maid who lives on the island?

This Shintohoproduction was based on a story by Sakae Tsuboi, entitled simply Koyomi (‘calendar’ or ‘almanac’) andfirst published in 1940. Tsuboi (1899-1967) was the youngest of five daughters fromShodoshima, so she may well have based the character of Mie on herself. Shealso wrote Twenty-Four Eyes, which isalso set on Shodoshima. Her only full-length work to have been translated intoEnglish, it was, of course, turned into a highly successful film by KeisukeKinoshita in 1954.

Like Policeman’s Diary (1955), the only otherfilm I’ve seen by director Seiji Hisamatsu, this one is also reminiscent ofKinoshita’s work. Looking back at my review of that film, I described it as ‘acharming, bittersweet comic drama from a more innocent age’, a descriptionwhich could equally apply to Five Sisters.However, unlike Kinoshita – who had a fondness for slightly gimmicky visualtechniques – Hisamatsu’s direction is the kind that never draws attention toitself. Nothing terribly dramatic happens in this film, yet somehow I was neverbored, and few films have dealt with the theme of marriage in such a light but thoughtfulway. It was screened in competition atCannes in 1955, but seems to have rarely been seen since, at least outside ofJapan.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Thanks to A.K.

March 29, 2025

Deep River Melody / 風流深川唄 / Furyu Fukagawa uta (‘Elegant Fukagawa Song’, 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #176

Hibari Misora

Hibari MisoraFukagawa, Tokyo, c.1925.Daughter (Hibari Misora) wants to marry childhood sweetheart (Koji Tsuruta),but he’s got no dosh. Family business runs into financial difficulties. Onlyway to save it is for daughter to marry repulsive rich dude (Masahiko Naruse).

(For a proper synopsis,see Hayley Scanlon’s review at Windows onWorlds here.)

When boiled down to itsbare bones, the plot of this Toei production is not only the same as that ofthe previous film I reviewed, GoldenDemon, but is basically a formula that has been used ad infinitum inJapanese literature and film. However, while in a Hollywood movie you could bealmost certain that the childhood sweetheart character would win the girl inthe end, in Japanese films it could go either way as audiences there havegenerally been much more willing to accept an unhappy ending. I’ll leave it toyou to guess the outcome in this one.

The film was based on a1935 novel of the same name by Matsutaro Kawaguchi, who was the senior managingdirector at Daiei when it was made, so it’s a little surprising that a rivalstudio chose to adapt it. Kawaguchi actually won the first Naoki Prize for thebook and went on to write many others, but as far as I’m aware, the only workof his to have been translated into English is Mistress Oriku – Tales from a Tokyo Teahouse. I’ve read a little ofthat and found it to be literature of a very lightweight and middlebrowvariety, so was a little surprised that it had been selected for translation.

DeepRiver Melody the film is well-made byactor-turned-director So Yamamura, but it’s not as interesting as his earlierpicture, The Crab Cannery Ship, whichwas based on a book by a communist author who fell foul of the authorities andwas killed as a result. Perhaps in tribute, Yamamura gives himself a minor rolehere as a communist who also gets into trouble with the police. Incidentally, Japan’srelationship with communism is an interesting one – the Japanese CommunistParty was founded in 1922, outlawed in 1925, then legalised by the occupationforces in 1945. In fact, it was almost encouraged by the Americans for a yearor two as an antidote to feudalism before they did a U-turn and begandiscouraging it but ultimately decided not to ban it…

Anyway, back to thefilm. Despite its rather hackneyed plot, it might have worked well with AyakoWakao and Toshiro Mifune in the leads, but here we get Hibari Misora and KojiTsuruta. Hibari was, of course, a huge singing star who mainly appeared inmusicals, but even though the Japanese title contains the word for ‘song’, she doesn’tget one in this film and the material tends to expose her limitations as anactress. She had some ability in that department, but unfortunately she justdid not have a very expressive face and that’s something that would have been veryhandy in this type of role. As for Tsuruta, well, he’s just not terriblyinteresting or charismatic here.

Weirdly, it turns out tobe Isuzu Yamada who gets to sing a song here, which she does while accompanyingherself on the shamisen. She alsogives what’s easily the best performance in the film as Hibari’s widowedfather’s forthright and not-to-be-messed-with mistress, who at one pointactually attacks Hibari's dad for discouraging his daughter from marrying the oneshe loves. In my view, Yamada was the most versatile character actress inJapanese cinema and the shortcomings of the leads are even more obvious incontrast with her remarkable talents. If she’d had a larger role, I’d recommendwatching the film for Yamada alone, but her screen time’s quite limited, soit’s probably not worth suffering through the misguided star pairing of Hibariand Tsuruta, which is to this film what that big lump of ice was to the Titanic. In terms of So Yamamura films,this one’s just… so-so (sorry!).

March 23, 2025

Golden Demon / 金色夜叉 / Konjiki yasha (1954)

Obscure Japanese Film #175

Jun Negami and Fujiko Yamamoto

Jun Negami and Fujiko Yamamoto

1890. Miya (FujikoYamamoto) is a young woman in love with her adopted brother, Kan’ichi (JunNegami). The feeling is mutual and they plan to marry. However, Miya’s parentswant her to marry the wealthy Tomiyama (Eiji Funakoshi) and persuade her thatit’s in Kan’ichi’s best interests too as then they’ll be able to afford to send him abroad to study, which will greatly improve his prospects.

Four years later, Miyais trapped in a miserable marriage to Tomiyama who, knowing that he’s notloved, takes every opportunity to bully and humiliate his wife, while Kan’ichihas taken employment as a debt collector for a much-hated female moneylender,Akagashi (Mitsuko Mito), known as ‘Foxy Shark’. She has only given him a jobbecause she wants to seduce him, and he finds himself in the position of havingto demand repayment of loans from his former friends…

Based on an unfinishednovel by Koyo Ozaki (1868-1903), the plot of this Daiei production must haveseemed old hat even in 1954. In fact, there had been numerous silent versions* ofthe novel as well as previous talkies by Hiroshi Shimizu in 1937 and MasahiroMakino in 1948. The title seems intended to reference the supposed obsessionwith money which Kan'ichi develops in an attempt to fill his void, but it’s justone aspect of the story that – in this film, anyway – never really convincesand feels like a mere contrivance. Another is his determination to remain sounforgiving towards Miya. What really takes the biscuit though is the fact thatthese two estranged lovers end up living across the street from each other!

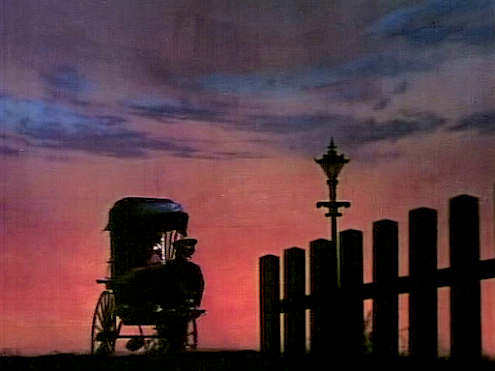

Otherwise, the film isquite well-made by director Koji Shima and the performances are good, withMitsuko Mito clearly having the most fun as the lustful loan shark. It won the1954 Asia Pacific Film Festival award for Best Film and received somedistribution abroad, arguably at the expense of other, better films, but thisis probably due to the fact that it was one of the earliest Japanese featurefilms to be made in colour. A lot of trouble was clearly taken to shoot scenes inpicturesque settings, such as a field of cherry blossom trees, a moonlit beachand a lonely road at sunset. Unfortunately, the copy I saw looked like a poorVHS transfer and the colours were horrible, but I did have the feeling that itwould probably look great in a good quality copy.

*A 1918 version castfuture film director Teinosuke Kinugasa (a male) as Miya, while Kinuyo Tanakaplayed the role in a 1932 film.

March 22, 2025

The Flesh is Weak / 美徳のよろめき / Bitoku no yoromeki (‘Faltering Virtue’, 1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #174

Yumeji Tsukioka

Yumeji Tsukioka28-year-old Setsuko(Yumeji Tsukioka), a former member of the aristocracy, has come down in theworld somewhat after the war and ended up marrying below her class to Ichiro (RentaroMikuni), whose uncouth table manners appal her.

Despite being a wife andmother, she’s unable to forget her first love, Tsuchiya (Ryoji Hayama),especially as she keeps running into him (small place, Tokyo!). When her motherdies, Tsuchiya attends the funeral and, while paying his respects, whispers inSetsuko’s ear that he will be waiting for her the following day at 3 pm at ashrine. They start seeing each other on the sly, but he seems like such a niceguy that she believes it will remain platonic and her conscience will be clear.However, he has a weird fixation with eating breakfast naked…

When Setsuko’s bestfriend, Yoshiko (Chikako Miyagi) – who is cheating on her own husband –arranges an excuse for Setsuko and Tsuchiya to sneak off to a hotel in Izutogether, Setsuko freaks out when her uncle turns up at the hotel with somegolfing buddies, stretching this film’s coincidence quota to the limit.Furthermore, Tsuchiya starts having non-platonic thoughts and tries to act onthem, but finds himself rebuffed by Setsuko, who feels that she must remainfaithful to her husband and certainly doesn’t want to eat breakfast naked withanyone…

This Nikkatsuproduction was adapted by Kaneto Shindo from a newly-published bestselling novelby Yukio Mishima (yet to be translated into English, but available in Chineseand Italian). The opening narration by actor Masaya Takahashi goes on for over10 minutes and betrays the film’s literary origins. However, while the endingis apparently close to that of the novel, what happens in between is quitedifferent, and it appears that Mishima’s original had Setsuko carrying on anextended sexual affair with Tsuchiya which results in two pregnancies, both ofwhich are aborted. They also eat breakfast naked together, but I guess you couldn’tshow that in a film in 1957 (so why have them talk about it, you may well ask).Anyway, although Mishima himself did not regard the novel as one of his seriousliterary efforts, he was not impressed and wrote in his diary that he could notimagine a more stupid movie.

It doesn’t help thatSetsuko is a self-pitying snob who is unnecessarily stern to her good-humouredmaid, making it hard to feel much sympathy for her. Nikkatsu’s biggest femalestar at the time, Yumeji Tsukioka, does as well as can be expected under thecircumstances, but Rentaro Mikuni is wasted in a role with little substance andRyoji Hayama fails to make much impression as Tsuchiya.

Chikako Miyagi faresbetter as the cheerfully amoral and flashily-dressed Yoshiko, and it’s nice tosee Koreya Senda – who had just played a rare leading role in director Ko Nakahira’sTemptation – pop up again here asSetsuko’s dad.

Nakahira also seemed to have a fondness for his namesake, actorKo Nishimura, who appeared in at least half a dozen of his films, includingthis one in which he has a small part as a blind masseur who sees things hisclient (Setsuko) can’t. If only Nakahira could have seen the defects in thescript…

Thanks to A.K.

March 17, 2025

Tales of the Inner Chambers / 大奥絵巻 / Ooku emaki (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #173

Yoshiko Sakuma

Yoshiko SakumaEdo Castle, c.1790. Whenvirginal chambermaid Aki (Yoshiko Sakuma) catches the eye of the shogun(Takahiro Tamura) while taking part in a dance performance, he decides to makeher his concubine. Aki’s elder sister, Asaoke (Chikage Awashima), is already employedat the castle, but once Aki enters the inner chambers, all family ties aresupposed to be forgotten.

Takahiro Tamura

Takahiro TamuraAki is extremelyreluctant at first, but has absolutely no choice in the matter; fortunately,the shogun treats her better than she expected. This may be because she remindshim of the girl he wanted to marry who died, leading him to become trapped in aloveless marriage of political convenience to Hagino (Hiroko Sakuramachi).Unfortunately, the favouritism of the shogun for Aki and the fact that this isto the advantage of Asaoke is greatly resented by some female members of thecourt, who split into two factions.

Chikage Awashima

Chikage AwashimaAki also has a youngersister, Machi (Reiko Ohara), who has a naïve idea of the inner chambers andwants to work there but is discouraged from doing so by her sisters. When therival faction offer her a position, the scheming between the two groups spiralsout of control, leading to blackmail, torture and murder...

Reiko Ohara

Reiko OharaSurprisingly,this Toei production is not based on a literary source – the intelligent screenplaywas an original work by Masashige Narusawa (who wrote and directed therecently-reviewed Cards Are My Life).In this case, the director is Kosaku Yamashita, perhaps best-known for the sameyear’s Big Time Gambling Boss. Itlooks like he put a great deal of care into this, and was ably abetted bycinematographer Juhei Suzuki (13Assassins), not to mention those responsible for the costumes and artdirection, whose combined talents make this film a feast for the eyes which exploitsthe colour format to the fullest. Ichiro Saito’s orchestral music is also an integralpart of the film and is another asset that marks it out as being far fromroutine.

Chikage Awashima

Chikage AwashimaAsfar as I can tell, the story itself has little historical basis. It unfoldsrather like a Jacobean tragedy and offers a pretty dark view of human nature.As Asaoke (another fine performance from Chikage Awashima) observes, “There isno righteousness or morality here, only female vanity and ostentation. You slayor be slain, kill or be killed.” Indeed, things do get violent, but notgratuitously so, and the film’s comparative restraint may be one reason it’snot better known. In fact, it’s a fine piece of work all round, and the onlyexplanation for its currently criminally low rating on IMDb (5.4) that occursto me is that maybe some people didn’t get the sexploitation movie they wereexpecting.

Yoshiko Sakuma and Hitomi Nozoe

Yoshiko Sakuma and Hitomi NozoeIwas surprised to see former Daiei star Hitmoi Nozoe in such a minor role as theone she has here, but then realised that she’d left Daiei to have kids in 1962and had only just begun attempting to resurrect her acting career.

A note on the title: Ooku is the name for the inner palace orchambers of Edo Castle, where the shogun’s harem was kept, while emaki means ‘picture scroll’ rather than‘tales’.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

March 9, 2025

Kokosu sezu / 告訴せず / (‘No Charges Filed’, aka ‘Without Complaint’, 1975)

Obscure Japanese Film #172

Kyoko Enami and Yukio Aoshima

Kyoko Enami and Yukio AoshimaKitani (Fumio Watanabe) is a conservative politician running forre-election with the help of his sister-in-law, Haruko (Kirin Kiki), and adviser,Mitsuoka (Ko Nishimura). When they needsomeone to go to Tokyo in order to collect 30 million yen in cash for briberypurposes, Kitani’s brother (i.e. Haruko’s husband), seems the perfect choice.He is Shogo (Yukio Aoshima), a schmuck who works as a chef and does whateverhis wife tells him. However, he’s also a big fan of crime fiction, and afterpicking up the cash he immediately absconds with it, hiding out at a hot springinn where he hooks up with one of the maids, Shino (Kyoko Enami)…

Based on an untranslated 1973 novel of the same name by prolificcrime writer Seicho Matsumoto, this co-production between Toho and theiraffiliate, Geiensha, treats the material like a comedy, although it’s seldomvery funny. The casting of Yukio Aoshima in the lead and the way he plays therole suggested to me that director Hiromichi Horikawa was looking for a newKeiju Kobayashi, who had starred in many of his earlier films. However, as thisfilm revolves partly around the world of politics and takes a swipe at the waythat elections are influenced by money, it’s also possible that Aoshima wascast due to his other career – he had actually entered politics as a Member ofthe House of Councillors in 1968 and, in 1971, “criticised thelarge amount of political donations made to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party by the business community” (JapaneseWikipedia). He eventually became Governor of Tokyo from1995 until 1999, when he lost out to another celebrity politician, ShintaroIshihara. Like Ishihara, he also dabbled in many different fields, being atvarious times a screenwriter, lyricist, TV personality, novelist, singer andeven film director. His independent 1966 film Kane (The Bell), which hewrote, produced, directed and starred in, screened at Cannes, but sounds like aterribly self-indulgent affair – IMDb offers the following synopsis: “YukioAoshima and several of his friends go to the seashore for a weekend, and Yukiofilms them as they enjoy the sand, the surf, and each other.” (Don’t think I’llbe rushing to seek that one out…) In any case, he’d never been called on tocarry a movie before, and on this evidence it’s not hard to see why, as he’s clearlynobody’s idea of a leading man and lacks Keiju Kobayashi’s subtlety and rangeas well.

The obligatory Eitaro Ozawa appearance

The obligatory Eitaro Ozawa appearance

One of the moreinteresting aspects of the film is that it features something called a futomani ritual, which I’ve never seenbefore. It’s a Shinto method of divination in which the shoulder-blade of astag is heated over a fire until it cracks, at which point the pattern of thecracks is interpreted for fortune-telling purposes. Incidentally, in the filmthis is performed by a priest played by Jun Hamamura, who looks almost healthyfor once.

Overall, though, thisfilm just doesn’t really know what it wants to be. A sequence featuring someweird freeze frames around halfway through does not help and made me thinkthere was a technical fault at first. And if it was supposed to be a comedy –which seems to have been the intention – you have to wonder why on earth theywould choose to go with the ending this films is lumbered with. It’s anacceptable time-passer, sure, but on the whole I’d have to call it a misfire.

March 6, 2025

Cards Are My Life / 花札渡世 / Hana fuda tosei (‘The Flower Card Business’, aka ‘Flower Cards Chivalry’, 1967)

Obscure Japanese Film #171

L-R: Chitose Kobayashi, Tatsuo Endo, Toru Abe, Tatsuo Umemiya

L-R: Chitose Kobayashi, Tatsuo Endo, Toru Abe, Tatsuo UmemiyaTheearly Showa period (1930s). Ryuichi Kitagawa (Tatsuo Umemiya) is a yakuza whoseparticular skill is gambling with hanafuda(‘flower cards’). His boss, Kasugai (Tatsuo Endo), has political ambitions and isin cahoots with Akiba (Ko Nishimura), a corrupt police detective. Kasugai hasan adopted daughter, Hisae (Chitose Kobayashi), who is also his lover, but shehas the hots for Ryuichi. However, Ryuichi is smitten with Umeko (HarukoWanibuchi), a female card cheat, but she has an asthmatic husband, ‘Blind Stone’Moto (Junzaburo Ban). Worse still, she attracts the attention of Kasugai, whodecides he wants her for himself.

Kasugaiorders Ryuichi to gamble against Moto over the fate of Umeko – if Ryuichi wins,Kasugai can do what he wants with her. It’s the ultimate giri versus ninjo (obligationversus inclination) dilemma – Ryuichi could lose on purpose, of course, butthis would go against his precious yakuza code of honour…

Ionly watch the occasional yakuza film, and so wasn’t too familiar with the starof this one, Tatsuo Umemiya (1938-2019), whose favourite own film it apparentlywas. I found him rather bland and it seems he had a career based mainly on hisphysique rather than acting ability. Signed to Toei as a ‘new face’ in 1958, hetootled around in mostly minor parts for a few years until the yakuza genreexploded around 1964, when Toei decided they might be milking their two maintough guy stars Koji Tsuruta and Ken Takakura a little too much and needed athird, so promoted Umemiya. According to Japanese Wikipedia, ‘His four goals inbecoming an actor were to sleep with a good woman, drink good alcohol, drive agood car, and have a house in a prime location with a beautiful sea view.’ Fair enough, I suppose, but he obviously wasn’t exactly Mr Deep. He laterbecame a Hideo Gosha regular, and actually really did lust after Haruko Wanibuchi, buther controlling mother made sure she kept him at arm’s length.

Thefilm was also significant for Wanibuchi, who had previously playedyoung and innocent types and was appearing as a sexy sophisticate for the firsttime here. However, despite her success in the role, she got married in 1968and disappeared from the screen for a few years. Really, though, the actinghonours here belong to the older members of the cast, including that inveteratescene-stealer, Ko Nishimura, Junzaburo Ban (from A Fugitive from the Past and Dodes’ka-den)and – all too briefly – the always excellent Sadako Sawamura, who has one scenehere in which she puts the incredibly nasty young woman Hisae firmly in herplace.

Perhapsthe main reason this film is so little-known is that it was effectively lost until2018, when it was finally found and restored. It’s both written and directed by Masashige Narusawa (1925-2021), who wasknown mainly as a screenwriter (notably for Mizoguchi) and only directed fivefilms, of which this was the third. He brings considerable style to this andhas a great deal of fun with tracking shots, unusual camera angles and screenswithin screens.

The card playing scenes arereminiscent of Shinoda’s Pale Flower (1964),while the influence of Kurosawa makes itself felt in the excellent slice-‘em-upscene near the end. Incidentally, I loved the hails of sparks from the clashingswords and don’t remember having seen that before. Of course, it was Kurosawa’sYojimbo (1961) that sparked thespaghetti western, so there’s also a certain irony in the fact that the mandolinsand trumpets featured in this film’s score strongly suggest the influence of thoseItalian westerns that had been made in the intervening years.

Overall, this film is better than it had any right to be, perhapspartly because the use of black and white seems to lend it a touch of class,but also probably because Narusawa was determined to make the most of one ofhis rare opportunities to direct. The result is a film interesting enough to satisfy both yakuza fans and those like me who are a little wary of the genre, not so much for its violent content as for its repetition of formula.

Thanks to A.K.

March 2, 2025

The Ladder of Success / 夜の素顔 / Yoru no sagao (‘The True Face of the Night’, 1958)

Obscure Japanese Film #170

Machiko Kyo in the moonlight scene

Machiko Kyo in the moonlight scene1944. Akemi (Machiko Kyo) is a traditional dancer entertaining thetroops at a military base in the south of Japan. When an air raid interruptsthe performance, she’s escorted to safety by Wakabayashi, a navy pilot (JunNegami) with whom she ends up having a fling. Three years later, made homelessby the war, Akemi arrives in Tokyo having travelled therein the hope of becoming a disciple to famed dance teacher Shino (ChikakoHosokawa). When her request is denied, she breaks down in tears before leaving,but Shino’s patron, Inokura (Eijiro Yanagi), who was listening in the room next door, feels sympathetic and urgesShino to change her mind, which she does. The maid is sent to fetch Akemi backand finds her waiting with an expectant smile on her face knowing that hercrocodile tears would do the trick…

Chikako Hosokawa

Chikako Hosokawa1953. Akemi has helpedShino build up a successful dance school with over 50 students. However, aftershe encourages her mentor to star in a new show, Shino is mocked by the pressfor being too old. To add insult to injury, Akemi seduces Inokura and Shinodiscovers them in flagrante. As a result, Akemi is expelled, but – with thesupport of Inokura – goes on to start her own dance school, which is soon agreat success. However, her most promising pupil, Hisako (Ayako Wakao), turnsout to be just as scheming and two-faced as Akemi and it looks like a case ofwhat goes around comes around…

Ayako Wakao and Machiko Kyo

Ayako Wakao and Machiko KyoThis Daiei productionmakes a great star vehicle for Machiko Kyo, although there’s surprisinglylittle dancing considering that Kyo was herself a trained dancer. In any case,she gives a rich and varied performance as a character who turns out to be lessone-dimensional than she first appears. The first indication that there’s moreto Akemi than meets the eye is during a memorable scene (perhaps the film’sbest) in which she has a moving moonlit encounter with an elderly female shamisen player reduced to buskingdoor-to-door (played by Hisako Takihana, a former star of the silent screen and wife of film director Tomotaka Tasaka). The old lady sings the song which gives the film its Japanesetitle and, for Akemi, she’s something of a Ghost of Christmas Future.

Wakao and Kyo

Wakao and KyoThe film is a littleless rewarding for Ayako Wakao fans as, while her role is an important one, shehas considerably less screen time than Kyo as well as a less multifacetedcharacter to portray. Having said that, she certainly has her moments here and,if you’ve ever wanted to see a catfight between Machiko Kyo and Ayako Wakao(albeit a rather one-sided one), this is the film for you. For their part, themen are pretty forgettable, although Eiji Funakoshi’s role as an avant-gardecomposer who collaborates with Akemi’s dance troupe provides the film’scomposer, Sei Ikeno, with an excuse to conjure up some interesting sounds forthe soundtrack, including a musical saw.

The first part of thefilm is in monochrome but, instead of black and white, a blue filter is used (the same effect which reappears in the later moonlight scene), which just seems odd. My guess is that this was done because the fact that the film was in colour was an important selling point in Japan in 1958, where colour films were not yet as common as in Hollywood. In fact, the film's posters state 'All natural colour' quite prominently. Perhaps the studio felt that, had they used standard black and white for the sequences set in the 1940s, some patrons might assume that the whole film would be like that, or at least feel cheated that part of it was. Another peculiarity of the film is a long split-screen montage ofAkemi and her pupils travelling all over rural Japan to give dance performancesoutdoors. Otherwise, it’s a fairly typical Daiei production, although a littlelonger than most at two hours. It’s the sort of story one might have expectedto come from the pen of Toyoko Yamasaki, but in fact Kaneto Shindo’s screenplaywas an original work. The director is Kozaburo Yoshimura, who frequentlycollaborated with Shindo, and had a reputation for bringing out the best infemale stars such as Machiko Kyo – a reputation which this film certainlysupports. Even though it lapses into full-on melodrama at the end, Kyo’s performancealone is enough to make this one worth watching.

Jun Negami

Jun Negami

February 26, 2025

Clouds at Sunset / あかね雲 / Akane-gumo (1967)

Obscure Japanese Film #169

Shima Iwashita

Shima Iwashita1937. After a prologue in which we see two soldiers deserting –one of whom is quickly captured – the story moves to Wajima, IshikawaPrefecture. Matsuno (Shima Iwashita) is a 19-year-old virgin working as a maidat an inn, where she is best friends with another maid, the older and moreexperienced Ritsuko (Mayumi Ogawa). When Ritsuko leaves for a better-paid jobas a hostess in Yamashiro Onsen 150 kilometres to the south, she invitesMatsuno to go with her, but Matsuno decides to stay behind for the time being.

She then meets Kosugi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), a kindly travelling salesman whostays at the inn where she works for a few nights. When she learns that he willalso be going on to Yamashiro and can help her find a job there, Matsuno decidesto join Ritsuko after all. However, she’s unaware that Kosugi has deserted fromthe army and has a dogged military policeman (Kei Sato) on his trail…

Clouds at Sunset was based on an untranslated 1964 novel of the same name byTsutomu Mizukami (or Minakami), whose work formed the basis for a number ofinteresting films, including The Temple of Wild Geese, Bamboo Doll of Echizen,A Story from Echigo, A Fugitive from the Past and Lake ofTears. Like the latter two, the film was adapted for the screen by NaoyukiSuzuki, a famously uncompromising screenwriter who frequently collaborated withTomu Uchida and had won two awards for AFugitive from the Past.

Directed by Masahiro Shinoda, like many of his films, Clouds at Sunset stars his wife, ShimaIwashita (in fact, the two are still married at the time of writing, aged 93and 84 respectively). 26 years old when the film was made, she is nevertheless thoroughlyconvincing as the young and innocent Matsuno and won both the Kinema Junpo and MainichiFilm Concours awards for Best Actress for her performances in this and Portrait of Chieko. The otherprincipals are also good, especially Mayumi Ogawa as her protective olderfriend (whom chance always seems to make unavailable at the crucial moment!).

As played by Tsutomu Yamazaki (the kidnapper from Kurosawa’s High and Low), Kosugi never comes acrosslike the scumbag one would expect considering the despicable way he later usesMatsuno to save his own skin. It’s made clear that he does this out of desperationrather than malevolence, and Matsuno continues to love him anyway. Somehow,this escapes feeling like the usual dubious male fantasy and Shinoda wisely leavesit open to question whether Matsuno is merely hopelessly naïve or is actuallythe only one perceptive enough to recognise Kosugi’s better nature.

Although distributed by Shochiku, the company for whom Shinoda hadbeen under contract until 1966, the film was the first independent productionby Hyogen-sha, Shinoda’s own company. All the more reason, then, to wonder whythis excellent film came to fall through the cracks and become perhaps theleast-seen of Shinoda’s works in recent years.

Aesthetically, the film looks and sounds great thanks to itssubtle Toru Takemitsu score and the often beautiful cinematography of MasaoKosugi which, appropriately, bursts into colour at each sunset.

Thanks to A.K.