M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 7

January 4, 2025

The Wild Goose / 雁 / Gan (1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #158

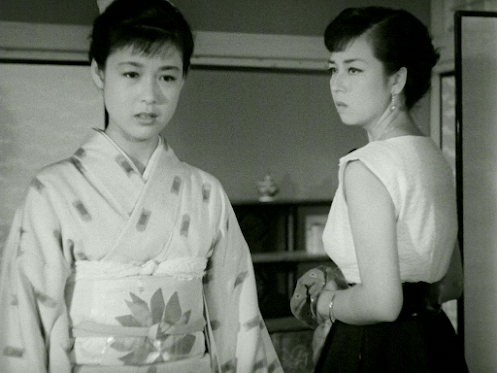

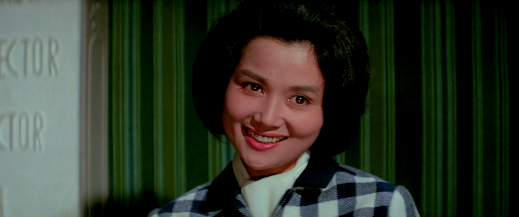

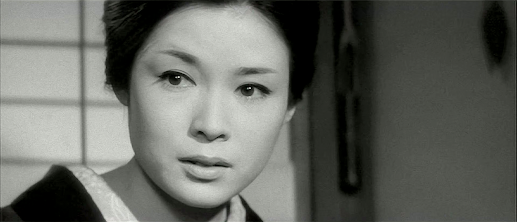

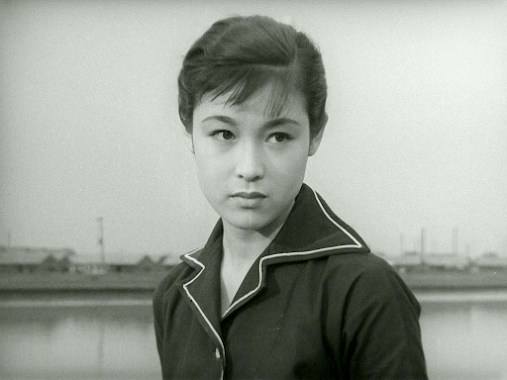

Ayako Wakao

Ayako Wakao

Tokyo, 1880. Otama(Ayako Wakao) is a young woman back living with her widowed father (TomosaburoIi) after having left her husband when she discovered he was actually abigamist and their marriage was illicit. Unfortunately for her, this means thatshe is now considered ‘soiled goods’ and finding a suitable husband will bemuch more difficult. Her father, a street vendor, is getting old and it’suncertain how much longer he’ll be able to push his cart around.

Wakao with Toyoko Takechi

Wakao with Toyoko TakechiTheir future looksbleak when a conniving old woman (Toyoko Takechi) comes with a proposal: arecently-widowed kimono-shop owner called Suezo (Eitaro Ozawa) wants Otama forhis mistress and will provide her and her father with separate places of theirown as well as an allowance each if they agree. (Supposedly, Suezo feels thathe can’t invite Otama to live with him because his two young children wouldn’taccept her). Seeing no better opportunities on the horizon and worried abouther father, Otama agrees.

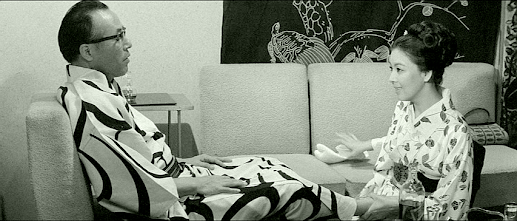

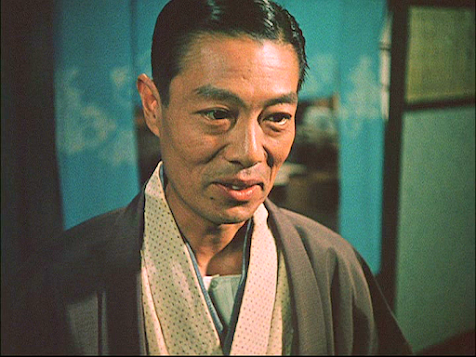

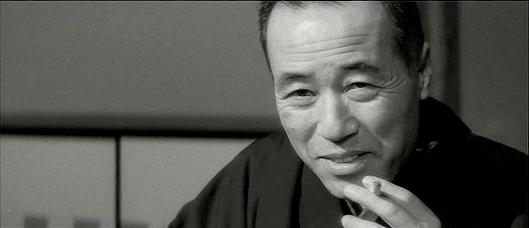

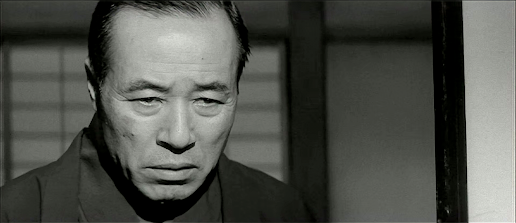

Eitaro Ozawa

Eitaro OzawaSuezo treats Otama welland everything is fine at first, but she soon discovers that she’s beendeceived once again – the old woman had lied to get Otama and her father toagree so that Suezo would cancel the debt she owed him. It turns out that, notonly is Suezo a loan shark rather than a kimono merchant, but his wife (HisanoYamaoka) is still alive and living with him. Despite her disillusionment, Otamacontinues as Suezo’s mistress as she’s simply not in a position to leave him.But then she begins to have romantic thoughts about Okada (Gaku Yamamoto), astudent who walks past her house every day…

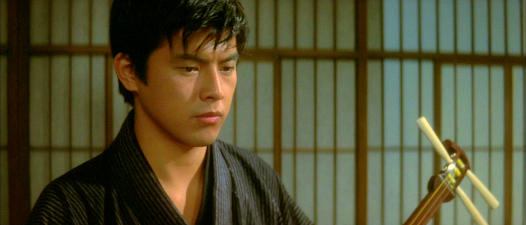

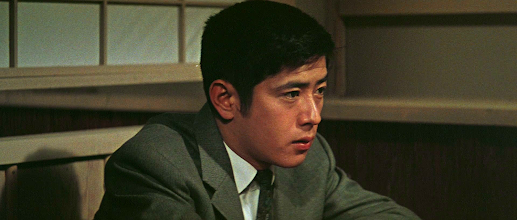

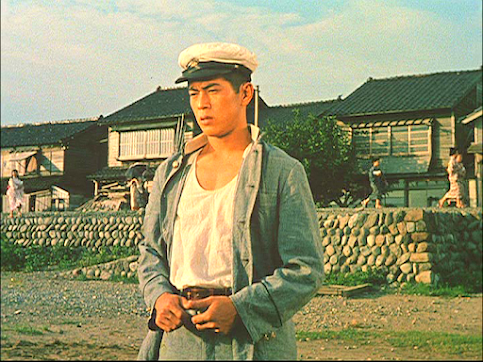

Gaku Yamamoto

Gaku YamamotoBased on a short 1913novel of the same name by Ogai Mori – himself a young medical student likeOkada at the time this story is set – this remake of Shiro Toyoda’sbetter-known 1953 version starring Hideko Takamine (also produced by Daiei) creditsthe same screenwriter (Masashige Narusawa) and follows the original picture almostscene-for-scene. For this reason, it may well seem superfluous and is probablydestined to live forever in the shadow of the earlier film. However, there aresome differences, and it does manage to improve on the original in a couple ofways. Toyoda’s film was shot in academy ration – standard for the time – whileby 1966, widescreen had long been the norm in Japan, and that’s the format usedhere. Whether this really adds much in itself is debatableconsidering that the cinematography in the first film was one of its notablefeatures, especially its striking close-ups of Takamine. What is much better, though, is the music –it may be a little over-dramatic at times, but it’s less cloying than in the1953 movie, and is also used more sparingly, which helps a great deal too. Theother main improvement for me was the casting of Gaku Yamamoto as Okada – hemay not be a star actor, but at least he doesn’t resemble a constipatedundertaker as the miscast Hiroshi Akutagawa did in the original.

In regard to thecasting of Suezo, the choice of Eitaro Ozawa was almost a no-brainer. If youwanted someone to play an unpleasant middle-aged male in a Japanese movie inthe 1950s or ‘60s, you probably either went with Eijiro Tono or Eitaro Ozawa –both founder members of the Haiyuza theatre company, incidentally – and Tonohad already played the character in Toyoda’s version. Ozawa is good here, buthe doesn’t manage to surpass Tono’s memorable portrayal of Suezo as aridiculous and pathetic character. The real villain of the piece is not Suezo,but the scheming old matchmaker (played to the hilt here by Toyoko Takechi) whocares not a damn whose lives she wrecks if there’s something in it for her.

Hisano Yamaoka

Hisano Yamaoka Reiko Fujiwara

Reiko FujiwaraTherest of the cast also give strong performances, especially Hisano Yamaoka asSuezo’s wife and Reiko Fujiwara as a woman who, reduced to streetwalking tosupport her children, serves as a sort of ghost-of-Christmas-future toOtama. Ayako Wakao is well-cast in herrole and gives her usual immaculate performance, but I felt that she didn’tquite nail Otama’s dichotomous combination of resigned pragmatism and girlishromanticism as well as Takamine.

For the most part, MasashigeNarusawa’s screenplay(s) could be taken as a model of how to adapt literaturefor the cinema, but there’s one part of the story that bothers me in both films– while Suezo is away for a day, Otama gives her maid the day off and sets about preparing an elaborate meal for Okada,intending to invite him into her home as he passes by so they can finally be alone together. This seems stupid considering thatshe has no idea if he will be available, or even accept if he is. And it just doesn't seem like something a woman in her situation would do because, if he did accept, somebody would be sure to find out about it and the two would become the subject of a scandal which would do neither of them any good. This absurdityis an invention of Narusawa’s as, in the book, she simply goes to thehairdresser and intends to start a conversation with him when she sees him coming rather than simply exchanging a silent greeting as they usually do.

Although both films are largely very faithful to Mori, the othermajor diversion from the source material concerns the scene which gives thestory its title. (It should be noted here that there are no plurals inJapanese, so the title can be translated as either The Wild Goose or The WildGeese). In the novel, Okada is persuaded by a fellow student to throw astone at some wild geese that have alighted in a nearby pond; to his consternation,he hits one and kills it. A comparison is made between the goose and Otama, theimplication of which (I think) is that, just as Okada did not mean to kill thegoose, neither did he mean to make Otama fall in love with him. In thisinterpretation, Otama could be said to be the ‘wild goose’ of the title.* However,for some reason this event is absent from the two films. In both, afterlearning of Okada’s imminent departure for Europe, Otama watches a goose flyaway, in effect making him the wildgoose.

The director, KazuoIkehiro, is far better known for action films, including several entries in theZatoichi series. He does an excellent job here, but it’s hard to give him agreat deal of creative credit as he was more or less following a blueprintcreated by Shiro Toyoda and Masashige Narusawa. He was active in television asrecently as 2022 and, at the time of writing, appears to be alive at the ripe oldage of 95.

*This bird symbolism is reminiscent of Chekhov’s The Seagull, which Mori may well have been familiar with in Germantranslation as he was also a translator of literature from German intoJapanese. Of course, there is a further avian metaphor in the caged bird thatSuezo gives to Otama as a gift and which is later threatened by a snake – the implicationthat Otama is in the same position is clear.

Thanks to A.K.

A good translation ofthe novel by Burton Watson is available as a freee-book here.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Watch the 1953 versionon my new YouTube channel here.

December 31, 2024

The Perennial Weed / 昭和枯れすすき / Showa kare susuki (1975)

Obscure Japanese Film #157

Kumiko Akiyoshi and Hideki Takahashi

Kumiko Akiyoshi and Hideki Takahashi

Harada (Hideki Takahashi) is a young police detective assigned to the Nishi-Shinjuku precinct of Tokyo. He lives with his younger sister, Noriko (Kumiko Akiyoshi), and the two are very close as they’ve had nobody else to rely on since their mother left and their father died years before. Originally from the country, they’ve been living in Tokyo for some years due to Harada’s career.

One day, Noriko fails to come home and Harada is shocked to see her walking in the street the following morning with a young yakuza thug, Yoshiura (Atom Shimojo). Harada begins tailing his sister and discovers that she has quit the fashion school she’s supposed to be studying at and is leading a double life. As if that were not troubling enough, a murder then occurs in which she may be implicated…

The splendidly-named Atom Shimojo

The splendidly-named Atom Shimojo

This Shochiku production was adapted by the omnipresent Kaneto Shindo from an untranslated story entitled ‘Yakuza na imoto’ (‘Yakuza Sister’) by Shoji Yuki, a prolific and popular writer best known for his hard-boiled crime fiction, but who worked in a variety of genres. Other adaptations of his work include the previously-reviewed Doro inu (1964) and Kinji Fukasaku’s Under the Flag of the Rising Sun (1972), though the only one of his books which seems to have made it into English is a children’s picture book entitled I’m Not a Dog.

Atom Shimojo and Kumiko Akiyoshi

Atom Shimojo and Kumiko Akiyoshi

The Japanese title of this film means something like ‘withered Showa-era silvergrass’, which bears no direct relation to anything in it. The title comes from a 1974 hit single by a duo known as Sakura and Ichiro which was also used as a theme song for the movie (and which the curious can listen to on YouTube here). The male and female singers compare themselves to withered silvergrass, observe how ‘even when trampled on, we endured’, and express their wish to ‘die beautifully’. Presumably, the inner feelings of Harada and his sister are supposed to be reflected in the song, but it was no doubt mainly a ploy to help sell the picture. In any case, the English title of The Perennial Weed has even less to do with the content of the film.

Hideki Takahashi and Mizuho Suzuki

Hideki Takahashi and Mizuho Suzuki

Directed by Yoshitaro Nomura, a filmmaker best-known for his Seicho Matsumoto adaptations such as Castle of Sand (1974), this features his usual semi-documentary approach to shooting on real locations wherever possible, something which is used to good effect here. The sparing use of music in this film is also an asset – most of what we hear on the soundtrack is actually the ambient sounds of the city, especially those of passing trains and traffic, which adds appropriately to the sense of realism.

Hideki Takahashi and Kumiko Akiyoshi are well-cast in the leading roles and give a good account of themselves. There’s an occasional suggestion that Harada’s feelings for his sister may be more than just brotherly, but Nomura ultimately leaves it an open question and seems much more concerned with the effect that city life has on his principal characters – especially Harada, who is suffering to a similar malaise to that of Robert Ryan in On Dangerous Ground (1951). Harada and Noriko are two refugees from rural Japan who have come to Tokyo for a better life but found a soul-crushing world of sleazy neon-lit bars and rundown, cramped apartment buildings among which criminals flourish and become arrogant while the police are dispirited and can only carry on by getting drunk every night after work. Harada has to deal with the reality that his sister has not lived up to his ideals and become the paragon of virtue he had hoped for, and many of the other characters – most of whom have also fled the countryside to live in Tokyo – express a similar sense of disillusionment. This is shown in its most extreme form at a murder scene Harada visits, where a loving father has killed his daughter rather than allow her to marry a man he knows is bad news. This has nothing to do with the plot, but the implication is that Harada could end up in a similar situation in regard to Noriko.

While this may be one of the director’s lesser-known works, it’s very well-achieved, keeps you watching and does offer some food for thought beyond a mere murder mystery. I’ve also rarely seen a specific side of a city’s atmosphere captured as well as it is here by Nomura’s regular cinematographer Takashi Kawamata. However, The Perennial Weed was perhaps too downbeat for most audiences and was reportedly a commercial failure.

Thanks to A.K.

December 26, 2024

Asakusa no yoru / 浅草の夜 (‘Asakusa at Night’, 1954)

Obscure Japanese Film #156

Setsuko (Machiko Kyo)is a dancer at a theatre in Asakusa, where she’s been having a relationshipwith the in-house playwright, Yamaura (Koji Tsuruta), for the past three years.He’s a nice guy whose idealism is beginning to give way to disillusionment ashe realises that the bosses will always prioritise putting bums on seats overart. Setsuko has a younger sister, Namie (Ayako Wakao), who has fallen in lovewith a young painter, Shisui (Jun Negami).

Setsuko is against the relationshipand tries to force Namie into breaking it off, citing Shisui’s low socialstatus as an adoptee as the reason. However, this seems to be merely an excusebecause Shisui was adopted by Tsuzuki (Osamu Takizawa), a successful painterwho is likely to make Shisui his heir. Things are further complicated when Komakichi(Hideo Takamatsu), the son of the yakuza boss who owns the theatre (TakashiShimura), makes an unexpected offer of marriage to Namie…

This Daiei productionwas based on a novel by Matsutaro Kawaguchi, who – perhaps not entirelycoincidentally – was executive director of Daiei Studios. The novel had beenpublished in serial form in Bungei Shunjumagazine, but seems never to have made it into book form. Like the protagonistsof this film, Kawaguchi grew up in Asakusa. He also went to school withdirector Kenji Mizoguchi, later writing or co-writing many of Mizoguchi’sfilms (as well as directing a few films of his own in the early 1930s), and wasthe father of Daiei star Hiroshi Kawaguchi. He must have been quite a guy, and was well-respected as a writer, even having a collection published in English (Mistress Oriku – Tales from a Tokyo Teahouse).

Jun Negami, Osamu Takizawa and Ayako Wakao

Jun Negami, Osamu Takizawa and Ayako Wakao

I was hoping forsomething a little grittier from this film, more along the lines of YuzoKawashima’s Suzaki Paradise: Red LightDistrict (1956). Instead, what we get is a rather contrived melodrama witha plot hinging on a massively unlikely coincidence. The film was written anddirected by Koji Shima, and occupies something of a middle ground among his films,being neither total hack work nor anything especially impressive artistically,although he throws in a few of his trademark symbolic shots (in this caseincluding rolling pachinko balls and a broken sake bottle) and there's also a well-staged fight scene which takes place in heavy rain.

Machiko Kyo fans willprobably enjoy this, especially as she had worked as a revue dancer herselfearlier in her career and gets to strut her stuff here. Ayako Wakao fans,however, are likely to find the film considerably less rewarding as she doesn’thave much of a role, although that shouldn't be too surprising as this was still early in her career and she wasn't yet a major star.

The remainder of the cast are fine but unremarkable, withthe exception of Takashi Shimura, who seems determined to steal each of his fewscenes by any means necessary, and is variously seen limping, massaging his foot, smoking with acigarette holder, using a lucky cat as an ashtray, and pruning his bonsai. It’sa masterclass in the actor’s guiding principle of there being ‘no small parts.’

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)December 23, 2024

Sweet Sweat / 甘い汗 / Amai ase (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #155

Machiko Kyo

Machiko KyoUmeko (Machiko Kyo) isa 36-year-old unmarried mother of a teenage daughter, Takeko (Miyuki Kuwano).They live in poverty in a cramped dwelling shared with her brother’s family andtheir mother (Sadako Sawamura). Umeko is used to trading on her looks invarious ways to get by but has an unfortunate habit of drinking too much. Shethinks she has it made when sleazy bartender Fujii (Shoichi Ozawa) fixes her upwith wealthy art dealer Gondo (Eitaro Ozawa), who intends to make her hislong-term mistress, but Gondo kicks her out when he discovers that she has notbeen entirely straight with him. Another chance of salvation seems to presentitself when she runs into old flame Tatsuoka (Keiji Sada), but this is a worldin which there are no fairly tale endings…

On 1 July 1964, Fuji TVbroadcast an original 1-hour drama entitled Abura deri (‘Oily Weather’) as partof their Theatre of 10 Million People series. Marking the first appearance ofMachiko Kyo in a TV drama, it was written by Yoko Mizuki, a screenwriter knownfor her collaborations with film directors Mikio Naruse and Tadashi Imai. SweetSweat, released on 19 Sep 1964, is an expanded version of the same story with ascreenplay also written by Mizuki. It’s impressive that Tokyo Eiga, the studiothat produced it, were able to have an entirely new 2-hour version in cinemasjust three and a half months later, especially as their film betrays no sign ofhaving been knocked out in a hurry. On the contrary, it gives the impression ofhaving been made with a great deal of care and attention to detail by everyoneinvolved, not least Shiro Toyoda, a director known for bringing a high level ofvisual flair to his films, many of which were literary adaptations.

Yoko Mizuki won a KinemaJunpo Award for Best Screenplay for this film, while Kyo deservedly won boththe Kinema Junpo Award and the Mainichi Film Award for Best Actress. She’sfirst seen here having a drunken cat-fight with another bar hostess, but wequickly learn that Umeko herself is a consummate actress – when she puts on herbest kimono and visits Gondo for the first time, he’s initially convinced thatshe really is the demure victim of misfortune she appears to be. It’s the typeof role that’s a gift for an actress, and Kyo is a joy to watch when she gets arole like this one that doesn’t require her to be too restrained.

It’s also interesting tosee Keiji Sada subverting his usual nice guy image in his final film rolebefore his untimely death in a car crash. Sada seemed keen to stretch himselfin his later films – Escape from Hell being another example – so it would havebeen interesting to see what he would do next had he lived. At one point in SweetSweat, his character even throws salt at Umeko as if she’s an evil spirit hemust ward off, though she would perhaps be more justified in throwing salt at him.Also notable in the cast is 22-year-old Miyuki Kuwano, who is entirelyconvincing as a 17-year-old high school student. Although this may not seemmuch of an acting feat, when compared with her leading role in The Shape ofNight the same year, it becomes obvious that she was also a versatile talent.

Mostly set in therun-down Tokyo neighbourhood of Shimokitazawa, then being torn apart forredevelopment, this is a terrific film with a tangible atmosphere of discomfort;everyone seems to be constantly fanning themselves or wiping the sweat off. Italso benefits from the nicely unintrusive music score by Hikaru Hayashi and excellentcinematography of Kozo Okazaki. Newly released on DVD in Japan, this is a filmripe for rediscovery and one which I think will start to receive more attentionin the near future.

Thanks to A.K.

December 20, 2024

A Portrait of Shunkin / 春琴抄 / Shunkinsho (1976)

Momoe Yamaguchi

Momoe YamaguchiDoshomachi, Osaka,early Meiji era (c.1870s). Okoto (Momoe Yamaguchi), the youngest daughter of thewealthy owner of a wholesale medicine company, has lost her sight due to achildhood illness. She takes a liking to Sasuke (Tomokazu Miura), a youngapprentice employed by her father, and soon he is the only person she willallow to escort her to her music lessons and help her with other tasks. Okoto becomesproficient at playing the instrument whose name she shares (the koto, the ‘O’ being a polite prefix),inspiring the devoted Sasuke to take up the more humble samisen, which hepractises in secret.

Initially, Sasuke gets into trouble for being more concernedwith looking after Okoto and learning music than he is about learning the trade.However, Okoto has become extremely stubborn and difficult to deal with sincelosing her sight, so her parents decide to release Sasuke from his normalduties and allow him to be Okoto’s full-time companion – even paying for him tohave music lessons from Okoto’s teacher – in the hope that this will soothe heranger and improve her character. Meanwhile,Okoto’s beauty has led to her attracting the attention of wealthy playboy Minoya(Masahiko Tsugawa), who begins laying plans to seduce her…

Yamaguchi with Masahiko Tsugawa

Yamaguchi with Masahiko Tsugawa

Later in the story,Okoto becomes a music teacher herself and takes the name of Shunkin, hence thetitle. Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1933 novella of the same name (available in a goodEnglish translation in the collection SevenJapanese Tales) was first filmed in 1935 by Yasujiro Shimazu in a versionstarring Kinuyo Tanaka. At the time, talking pictures were still relatively newin a Japan which was lagging a few years behind Hollywood in this department.As the story features both music and birdsong quite prominently, it must haveseemed a good choice by which to exploit the possibilities of the new soundmedium. Other versions followed: in 1954, Daisuke Ito directed Machiko Kyo asOkoto, while in 1961 Teinosuke Kinugasa made a third version starring FujikoYamamoto. Up to this point, each film had featured a big female star, with therole of Sasuke being played by a more minor male co-star. Kaneto Shindo brokethis pattern in 1972 with his version, entitled Sanka (‘Hymn’), which featured the unknown Tokuko Watanabe in therole. Shindo also restored the novella’s framing device, which uses afirst-person narrator visiting the graves of Okoto and Sasuke and meeting theirformer maid – now an old woman – whom he persuades to tell him their story. In Sanka, Shindo himself plays thenarrator, while his mistress Nobuko Otowa takes the role of the maid, so itseems likely that Shindo followed the book in this regard mainly to provide arole for Otowa, who was too old to play Okoto.

Given that Okotocontinues to treat Sasuke like a servant even after they become lovers and isoften cruel to him, Tanizaki’s story can equally be interpreted as a story of howSasuke’s unwavering devotion represents the ideal of true love, or as a storyabout the perfect sado-masochistic relationship. Unlike the previous film versions, Shindo’svery much emphasizes the latter reading, even going so far as to have Sasukereverently burying his mistress’s shit in the garden every day – a detail not presentin the book. However, considering that Tanizaki’s title was not Okoto and Sasuke but A Portrait of Shunkin, it’s alsopossible that his main concern was to provide a character study of a womanwhose sense of pride means that she absolutely refuses to behave like a victimand for that reason would rather be thought cruel than allow anyone to feel sorryfor her.

Made just four yearslater, director Katsumi Nishikawa’s 1976 version – the fifth – returns to themore conventional interpretation of the tale as a tragic love story, with ascreenplay co-written by Nishikawa and Teinosuke Kinugasa, who had directed the1961 version. A lot of care evidently went into the making of this one, and it’svery pretty to look at. Its raison d’etre was clearly to provide a vehicle forstars Momoe Yamaguchi and Tomokazu Miura. Yamaguchi – who first came to fame asa 13-year-old pop singer in 1972 – was such a phenomenon in Japan in the 1970sthat she even has a chapter devoted to her in Mark Schilling’s Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture.Her first major film part was in a version of another oft-filmed literary work,Yasunari Kawabata’s The Izu Dancer in1974, the first of seven films for director Katsumi Nishikawa but also, more significantly, the first of 12 features in which she co-starred with TomokazuMiura. The two soon became known as the ‘golden combination’, and were marriedin 1980, at which point Yamaguchi retired from show business to become afull-time wife and mother but continued to be hounded by both the media and herobsessive fans.

Yamaguchi and Miuragive decent performances in A Portrait ofShunkin, as do the rest of the cast, and it’s a well-made film. However, withMasaru Sato’s syrupy music ladled all over the soundtrack, I found its prettysentimentality a bit cloying for my taste and prefer Shimazu’s early attempt oreven Shindo’s more eccentric take on the story.

December 8, 2024

The Twilight Years / 恍惚の人 / Kokotsu no hito (‘Senile Person’, 1973)

Obscure Japanese Film #153

Hideko Takamine and Takahiro Tamura

Hideko Takamine and Takahiro TamuraAkiko (Hideko Takamine)is a middle-aged woman with an office job who lives with her husband, Nobuyoshi(Takahiro Tamura), her teenaged son, Satoshi (Izumi Ichikawa), and herparents-in-law, Shigezo (Hisaya Morishige) and his wife Haruyo (Matsuo Ono). AfterHaruyo dies suddenly, Shigezo begins acting strangely and ceases to recogniseNobuyoshi, but continues to recognise Akiko. When Shigezo’s other child, Kyoko(Nobuko Otowa), who is also Nobuyoshi’s sister, visits, he fails to respond toher as well and it gradually becomes apparent that he’s suffering from seniledementia. His behaviour turns increasingly child-like, unpredictable andembarrassing and, being the only person he pays any kind of attention to, it isleft to Akiko to look after him while also trying to hold down her job and be awife and mother…

Hisaya Morishige

Hisaya MorishigeWith a screenplay by HidekoTakamine’s husband, ZenzoMatsuyama, The Twilight Years wasbased on a 1972 novel ofthe same name by Sawako Ariyoshi* which had become an unlikely bestseller,shifting nearly two million copies in Japan. It’s an admirably unsentimental film which pullsno punches and is not an easy watch. However, if you’re up for a film aboutsenile dementia – and I certainly wouldn’t blame you if not – there’s much toappreciate here. The performances are excellent all round, and it’s a littlesurprising that neither Hideko Takamine nor Hisaya Morishige (unrecognisable asthe star of The Naked Executive, madejust 9 years previously) were nominated for any awards for their excellent workhere. Morishige was 60 at the time but plays an 84-year-old most convincingly (thoughthis is partly due to good make-up as well). Nobuko Otowa also makes amemorable character out of the pragmatic and rather slovenly Kyoko.

Nobuko Otowa

Nobuko OtowaAs the book had been sosuccessful, a film version probably seemed a safe investment, although it doeslook like it was made on a fairly low budget. It was the first film produced bythe Geiensha Company, which was affiliated with Toho and was to produce afurther nine films over the following decade. Veteran director Shiro Toyodaproves himself very adaptable here, shooting in academy ratio black and whiteand often using handheld camera and natural light. Considering Toyoda’s age atthe time (67) as well as the subject matter, it’s impressive that this neverfeels like an ‘old man’s movie’ – the younger characters, such as Akiko’s sonand the students who come to live in the spare room in exchange for helping tolook after Shigezo – do actually seem like believable people rather than someold fuddy-duddy’s idea of teenagers. There’s also a fine, tasteful music score courtesyof Masaru Sato.

Hisaya Morishige

Hisaya MorishigeThe story was thriceremade for television, most recently in 2006 starring Rentaro Mikuni.

*Although out of print,an English translation of the novel was published and is not difficult to findin used copies for sale online.

Thanks to A.K.

December 7, 2024

The Kii River / 紀ノ川 / Kinokawa (1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #152

Yoko Tsukasa

Yoko TsukasaWakayama, 1899. Hana(Yoko Tsukasa) is a young woman from a highly-respected family who marriesslightly below her class as her husband, Keisaku Shintani (Takahiro Tamura), isjudged to be a young man of exceptional promise. However, their married lifegets off to an awkward start when Hana joins her husband to live in his familyhome, which is also shared by his brother, Kosaku (Tetsuro Tanba). He takes aninstant dislike to her, perhaps because he resents her for being from a familyof higher status, or perhaps because he’s secretly in love with her himself. Meanwhile,Keisaku spearheads an ambitious engineering project to build flood defencesalong the Kii River which will protect the surrounding farmlands in the eventof heavy rain.

Takahiro Tamura and Tetsuro Tanba

Takahiro Tamura and Tetsuro Tanba

As the years pass, theinfluence of the West increases and the modernisation of Japan begins. Peoplebegin to wear Western clothes more and more, and even express theirappreciation of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. We see the introduction of newconsumer items such as ready-made cigarettes and bicycles, as well as newideas, including democracy, communism and the emancipation of women. Kosakueventually mellows towards his sister-in-law, who has a daughter, Fumio (ShimaIwashita), with whom she has little in common. Fumio is an outspoken rebel wholeads a protest when one of her teachers is unfairly dismissed and regards herparents’ ideals as hopelessly out-of-date. But after Fumio has a daughter of herown and Hana enters old age as the family prepare to face the tribulations of WorldWar Two, their animosity too will fade…

Keisaku’s obsessionwith building flood defences may be symbolic of a desire to control the forcesof nature – something which the Shintani family learn on multiple occasions isthe one thing their wealth and status will never enable them to do. There isalso symbolism of a weirder variety in the motif of the white snake which livesin the attic and will drop dead onto the tatami below at the very moment themistress of the house expires.

Running nearly threehours, this major Shochiku production was based on a 1959 novel of the samename by Sawako Ariyoshi (1931-84), whose work had also provided the sourcematerial for Keisuke Kinoshita’s even longer The Scent of Incense (1964), and would go on to form the basis offilms such as Yasuzo Masumura’s The Wifeof Seishu Hanaoka (1967), Tadashi Imai’s The Time of Reckoning (1968) and Shiro Toyoda’s The Twilight Years (1973). Ariyoshi wasfrom Wakayama, where this story is set, and elements of it are said to havebeen based on her own family’s history. However, she had little in common withthe character of Hana, being more similar to that of Fumio, although neithercharacter should be taken as her alter ego. English translations of her workinclude this novel (as The River Ki),The Twilight Years, and The Wife of Seishu Hanaoka (as The Doctor’s Wife).

Director NoboruNakamura had already made three films with Shima Iwashita at this point, includingthe excellent Koto (1963). Herperformance is sometimes a little on the broad side here, whereas YokoTsukasa’s is quite understated. It was Tsukasa who won most of the majorJapanese film awards for her performance in TheKii River, largely (I suspect) because she is convincing in regards to theageing of her character from around 20 to 70. This is reminiscent of thetransformation of Machiko Kyo in AWoman’s Life (1962), another female-focused period family saga of a typewhich seems to have been popular in Japan around this time. Personally, though, I felt that the strongest performance here comes from Tetsuro Tanba as the surly brother-in-law, although the reasons for his change of attitude towards Hana are not entirely clear.

TheKii River is beautifully shot by cinematographer ToichiroNarushima, whose credits are few but who also shot Koto, The Shape of Night (1964,again for Nakamura) and Merry ChristmasMr Lawrence (1983). I’ve rarely seen a film with so few close-ups, and onething I’ve always liked about Japanese cinema is that close-ups are generallyused far more sparingly than in Hollywood. Another strength of the film is thescore by Toru Takemitsu, which is also used sparingly, and features hisbrilliant modernist take on traditional Japanese music.

When made into films,such sagas spanning periods of many years are often limited in the amount ofdepth possible in regard to their characters and can rely too much on skippingfrom one melodramatic incident to the next. The film in question is also guiltyof this to some extent – there seem to be alot of sudden deaths occurring sporadically throughout – but the aestheticsof the film are of such a high standard that it remains a true cut above the rest. For these reasons, The Kii River may fall slightly short of masterpiece status, but certainly deserves recognition as a classic of the Japanese cinema.

December 1, 2024

The Naked Executive / 裸の重役 / Hadaka no juyaku (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #151

Hisaya Morishige

Hisaya MorishigeHidaka (Hisaya Morishige) is a widowed office manager with agrown-up daughter, Keiko (Yuriko Hoshi). Now 50 years old, he has a reputationfor strictness and is, in fact, a bit of a bastard who has no sympathy forthose less fortunate such as Hamanaka (Seiji Miyaguchi), an employee nearingretirement age who begs to be kept on as he has a sick wife to support.

When Hidakagets promoted to senior manager and is to be sent on a lengthy business tripabroad, he reluctantly agrees to help Hamanaka before he departs, but seems tohave an ulterior motive. Hidaka has learned to his horror that Keiko has beenseeing Okuda (Kiyoshi Kamoda), whom he regards as his most useless employee,and he wants Hamanaka’s help in ending their relationship.

However, upon hisreturn, Hidaka is disconcerted to find that Keiko has not only stubbornlyrefused to cut ties with Okuda, but encouraged him to marry her in spite of herfather’s opposition. Hidaka realises he has no choice but to accept the situation,but as a result he finds himself humbled in the eyes of the big boss (EijiroTono) and loses his self-confidence. Beginning to suffer from insomnia anddepression, he finds unexpected solace in the arms of streetwalker Sakiko(Reiko Dan)…

This Toho production is the sort of Japanese film not shown veryoften in the West, probably because Westerners used to marrying whoever theywant and not having to kow-tow to their bosses to the extent we see here mayfind it hard to relate to. An awful lot of arse-kissing goes on in Hidaka’soffice, although it’s simply portrayed as perfectly normal and not satirised atall. In fact, I was surprised to see barely a hint of true criticism of themoney- and career-obsessed world Hidaka inhabits. However, the veryuber-Japaneseness of the film does lend it a certain cultural curiosity value.

It’s unusual to see a character like Hidaka as the protagonist ofa movie. The fact that he’s played by Hisaya Morishige led me to expect acomedy, but I think this is supposedto be a drama, toothless as it may be. Morishige is an actor little-known abroad,but who played leads for director Shiro Toyoda in Marital Relations (1955) and Shozo,A Cat and Two Women (1956). Hidaka is a character who undergoes a complete,almost Scrooge-like transformation by the end of the film. The problem is thatnone of it is at all convincing. We are in some weird kind ofmale-wish-fulfilment fantasy land here with the vivacious Reiko Danas a highly unlikely streetwalker. It’s not Dan’s fault, though, it’s just awhitewashed portrait of someone reduced to this profession – the contrast withMiyuki Kuwano in the same year’s TheShape of Night could not be more pronounced.

From an original screenplay by regular Naruse collaborator ToshiroIde, The Naked Executive is competentlybut rather blandly directed by Yasuki Chiba, a veteran who was then undercontract to Toho. He seems to have been well-regarded in his time, but the onlyother film I’ve managed to see by him so far is a rather wonderful comedyentitled Tokyo Sweetheart (1952) starringToshiro Mifune and Setsuko Hara.

November 24, 2024

On This Earth / 地上 / Chijo (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #150

Hitomi Nozoe and Hiroshi Kawaguchi

Hitomi Nozoe and Hiroshi KawaguchiKanazawa, centralJapan, c.1920. Heiichiro (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) is a student who lives in a smallfirst floor flat in the red light district with his widowed mother, Omitsu(Kinuyo Tanaka), who earns her living from needlework. Although once part of awealthy family, they are now struggling to get by, and Heiichiro’s school feesare overdue.

One evening, a naïve country girl, Fuyuko (Kyoko Kagawa), isbrought to the geisha brokerage downstairs by her uncle and sold. The broker (KichijiroUeda) intends to sell her on to a geisha house the next day, but not beforehe’s taken advantage of her himself. When he gets drunk and tries to rape Fuyuko,she flees the house and is taken in for the night by Omitsu. However, she hasno choice but to return in the morning, when she is taken to the geisha house asplanned and must prepare to learn her new trade. Omitsu is subsequently offereda job as a live-in seamstress at the same geisha house, so she and Heiichiro goto live there. Omitsu develops an affection for Heiichiro, but resigns herselfto her fate, and is ordered by the head of the house (Kyu Sazanka) to sleepwith local bigwig Amano (Shin Saburi).

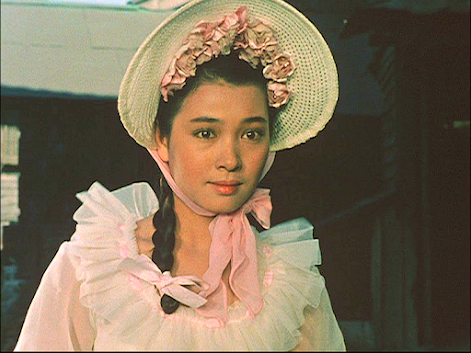

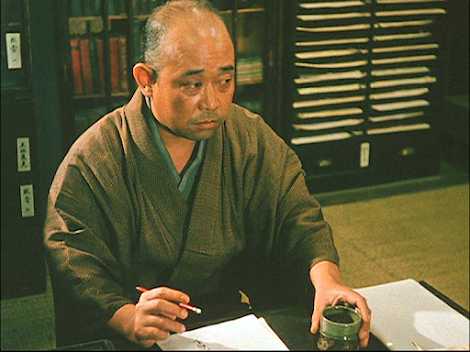

Meanwhile, Heiichirohas a chance meeting with his former childhood sweetheart, Wakako (Hitomi Nozoe),and he falls in love when he sees her in a ridiculous Bo Peep bonnet and dress. She’s thedaughter of a wealthy factory owner whose employees go on strike. One of theseemployees is a friend of Heiichiro’s, which leads to him being suspected ofhelping the strikers. Despite theefforts of a sympathetic teacher (Kinzo Shin), Heiichiro finds himself expelledfrom school by the headmaster (Eitaro Ozawa) …

OnThis Earth was adapted by Kaneto Shindo based on the firstpart of a long four-part autobiographical novel by Seijiro Shimada (1899-1930),whose life is closely reflected in the character of Heiichiro. Shimada wasapparently something of an angry young man, and after his book was a hugesuccess he was said to have become unbearably arrogant, which led to his earlysupporters dropping away and his success being a short-lived one. Shimada’s dissatisfactionwith the state of the world and socialist beliefs are evident in the film – Shindoand director Kozaburo Yoshimura portray a society in which the vast majority acceptits inherent injustice unquestioningly because the exploitative economiceco-system in which they must survive is so inflexible. If – like Heiichiro’suncle (Taiji Tonoyama), who is in a position to help due to his job working for the council, butrefuses to stick his neck out – they are lucky enough to have found themselvesa niche, they dare not risk losing it. The filmmakers are obviously in sympathywith Shimada on this point, and make it pretty clear how they feel – forinstance, a scene in which a female striker is dragged off screaming by thepolice cuts abruptly to a shot of fat cat Saburi enjoyinghimself in a geisha house.

Where the film is lesssuccessful is in the way that every female character in the film seems to concludethat Heiichiro is the best thing since sliced bread within a few seconds ofmeeting him. In fact, the character is mysteriously held in such high esteem byeveryone that even Wakako’s brother (Keizo Kawasaki) encourages her love affairwith Heiichiro against their parents’ wishes, and Fukai (Yosuke Irie), a mutualfriend of Heiichiro and Wakako, who might have been expected to have feelingsfor Wakako himself, is only too willing to act as a go-between. It could wellbe that this assumed acceptance that Heiichiro is special without any apparentjustification is also a weakness in the novel, which would make sense givenShimada’s reputation for arrogance, but in any case, I felt that it workedagainst the film.

Kyoko Kagawa and Kinuyo Tanaka

Kyoko Kagawa and Kinuyo Tanaka

OnThis Earth benefits from a strong cast, but the story isnothing special and the cliché count is high. The main reason it remains worthwatching in my opinion is the cinematography – the film was shot (much of it onlocation) using Daiei’s own colour process and was one of their last using theold academy ratio format, but it looks rather wonderfully like a movingpainting.

Bonus trivia: This wasthe second film (after Masumura’s TheKiss) out of 21 to co-star Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Hitomi Nozoe. They marriedin 1960 and remained together until his death in 1987.

Thanks to kagetsuhisoka for the English subtitles, which can be found here.

Additional thanks to A.K.

November 17, 2024

Tokyo Onigiri Girl / 東京おにぎり娘 / Tokyo onigiri musume / (aka ‘Triangle Moods’, 1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #149

Ayako Wakao and Ganjiro Nakamura

Ayako Wakao and Ganjiro Nakamura

Ganjiro Nakamura and Murasaki Fujima

Ganjiro Nakamura and Murasaki Fujima

Mariko (Ayako Wakao) is the daughter of Tsurukichi (GanjiroNakamura), a widowed tailor whose business in Shinbashi, Tokyo, has ground to a halt due to hisstubborn refusal to cater to changing fashions. It doesn’t help that he’s alsoan inveterate gambler who pays frequent visits to a mah-jong parlour owned bysexy widow Hama (Murasaki Fujima). With debt collectors calling, Mariko decidesto take matters into her own hands and convert part of the shop into an onigiri (rice ball) eatery with a loanfrom Tsurukichi’s former apprentice, Murata (Keizo Kawasaki).

Meanwhile, her aunt (Sadako Sawamura) thinks it’s time Mariko wasthinking about marriage and, hoping that it will push the two together, tellsher that her childhood friend Goro (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) is secretly in love withher. However, in reality he’s more interested in Midori (Junko Kano), a dancerwho turns out to be Tsurukichi’s estranged daughter from an illicit relationshipwith a geisha. While all this is unfolding, Mariko is also being pursued bywealthy businessman Tashiro (Yunosuke Ito), who incurs the displeasure of her over-protectiveand pugnacious chef Sanpei (Jerry Fujio)…

From an original screenplay by two not very distinguished writers,this Daiei comedy proves to be pretty thinly-stretched and inconsequentialstuff. Little more than an excuse to show off its star in another interminablevariety of costumes, it’s one for hardcore Ayako Wakao fanatics only andcontains one of her least interesting performances. The film is indifferentlydirected by Shigeo Tanaka, but occasionally enlivened by its supporting cast,with Murasaki Fujima, Yunosuke Ito and Jerry Fujio all quite funny in theirvery different ways.

Jerry Fujio, who was co-lead with Jo Shishido in A Colt Is My Passport (1967) and alsoappeared in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961)and Dodes’ka-den (1970), was aninteresting person. Born in 1940 to a Japanese father and an English mother inJapanese-occupied Shanghai, where his family all spoke in English, he moved toJapan with his parents after the war. According to Japanese Wikipedia, he andhis mother faced discrimination; she became addicted to alcohol and died agedjust 28 clutching a bottle of whisky. If that were not bad enough, Fujio’sfather abandoned him shortly after. While still in his teens, Fujio became abodyguard for a yakuza gang, but in 1957 he gave an impromptu performance ofElvis’ ‘Hound Dog’ in a jazz bar and was signed by an entertainment agency,taking the name of Jerry after American comedian Jerry Lewis. Even afterbecoming successful as a singer and actor, however, he could not quite shakeoff his yakuza past; on one occasion, finding himself attacked by three yakuza inthe street, he fought back so hard that he broke three of his attackers’ ribsand four of their front teeth before the police showed up and arrested him for ‘excessiveself-defence’!

As for the title, how this film became known in English as Triangle Moods, or what that even means,is anyone’s guess…

Thanks to A.K.