M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 4

May 23, 2025

Yojohan monogatari: Shofu shino / 四畳半物語 娼婦しの (‘Tale of the Four and Half Mat Room: Prostitute Shino’, 1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #189

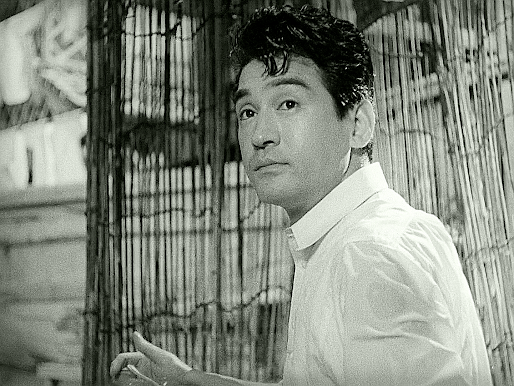

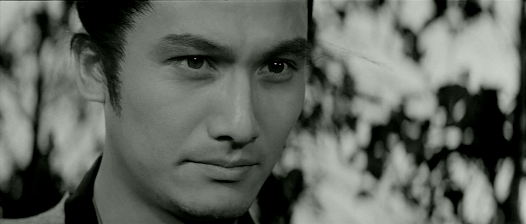

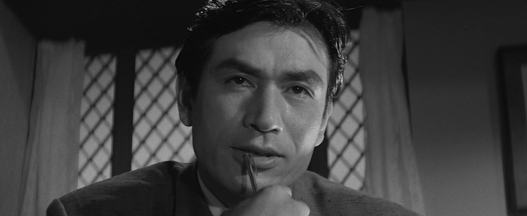

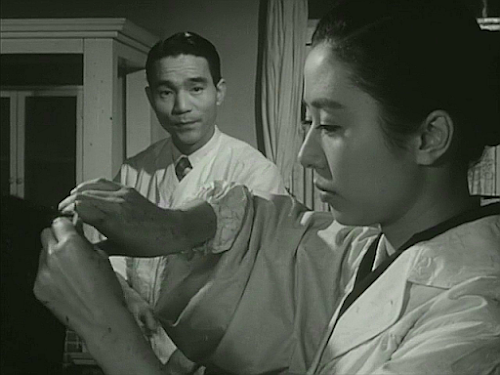

Takahiro Tamura and Yoshiko Mita

Takahiro Tamura and Yoshiko MitaShino (Yoshiko Mita) is an amateur geisha working under the nameof O-Shige at a modest geisha house run by the money-loving Taneko (MichiyoKogure), where she also lives. This means that she lacks the musical anddancing skills of a true geisha and simply sleeps with men for money – notbecause it’s the life she wanted to lead, but because she has taken it uponherself to pay off his father’s debts so that he can avoid prison. Shino isinvolved with Ryukichi (Shigeru Tsuyuguchi), who works informally as Taneko’sprocurer, but he’s a lazy sponger, so she’s naturally not in love with him.

One day, Tadasu (Takahiro Tamura) visits the geisha house as a newclient. Compared to most of her customers, he’s kind and gentle, and the twofall in love. However, being a former samurai reduced to pickpocketing, he can’tafford to buy her freedom. He resolves to go straight, but meanwhile Ryukichibecomes jealous of their relationship and begins plotting revenge…

Like the previously-reviewed CardsAre My Life, this was one of just five films written and directed byMasashige Narusawa, who was more usually a screenwriter only. This one is anadaptation of a short story by Kafu Nagai first published in 1917 – a storywhich went on to have a controversial history when a second, pornographic versionappeared and began to circulate on the black market. Nagai claimed thatsomebody else had added the explicit material without his knowledge, but manythought he had written it himself. After the later version was finally posthumouslypublished in 1972, the magazine publisher responsible was taken to court andcharged with obscenity. In any case, although Toei studios based their film onthe earlier version, their choice of it as material was one of the tentativesteps they were taking at the time to introduce more eroticism into their filmsas a means of competing with television, where such adult themes were notallowed.

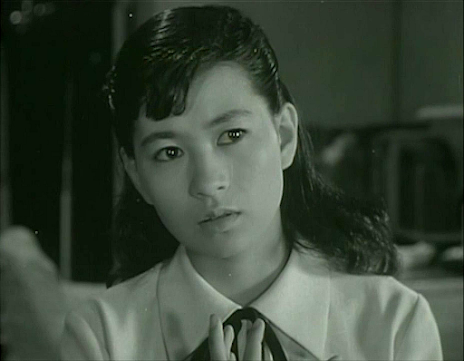

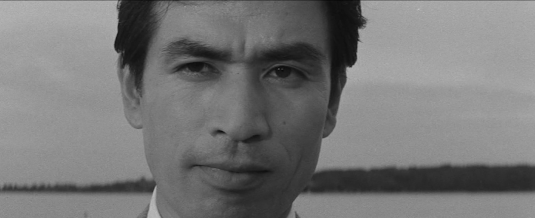

Yumiko Nogawa and Yoshiko Mita

Yumiko Nogawa and Yoshiko Mita

As a film set in a single location, albeit with quite an elaborateexterior set as well as the interior one, this was also probably quite a cheapfilm to make, although it never looks it. Narusawa (who had studied underMizoguchi) uses long takes with few close-ups and little cutting – a style I’vealways admired as I feel that it promotes naturalistic acting and makes theviewer feel less led by the nose than in the many films which frequently cutfrom one close-up to another. Cinematographer Juhei Suzuki – who shot 13 Assassins (1963) and Tales of the Inner Chambers (1968) – also deserves credit for his mobilecamerawork, which enabled Narusawa to have only 39 cuts in the entire film.

On the other hand, the performances are adequate but notexceptional and the story is not terribly compelling, featuring as it does thetypes of characters and situations we’ve seen many times before. Narusawaretains the framing device used by Nagai (here featuring narration by amostly-unseen Eijiro Tono), but I’m not sure it added much. The one really poor choice,though, is the easy-listening jazz score by Harumi Ibe, which just seems out ofplace in a Japanese period film, especially when the strummed guitar andaccordion kick in, which lend a distinctly inappropriate French flavour to theproceedings!

Thanks to A.K.

May 17, 2025

Ths Shogun and His Mistresses / 大奥(秘)物語 / Ooku maruhi monogatari (‘Secret Tales of the Inner Palace’, 1967)

Obscure Japanese Film #188

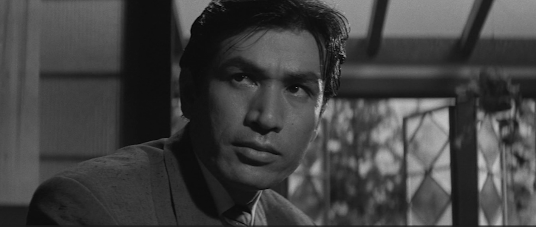

Masaya Takahashi

Masaya TakahashiThree stories set in the vast and labyrinthine inner chambers of EdoCastle during the reign of the sixth shogun, Ienobu Tokugawa, who held thetitle from 1709-12. (Nearly 50 at the time, Tokugawa is portrayed here as asomewhat younger man by the 37-year-old Masaya Takahashi.) With the exceptionof the shogun, only women are permitted in the inner palace, where power playsand factional battles are the norm…

Junko Fuji (left) and Reiko Hagi

Junko Fuji (left) and Reiko Hagi

In the first story, Fusa (Reiko Hagi) is brought to the castle atthe request of concubine Okon (Junko Miyazono), who is in poor health and nolonger able to bear children, in the hope that she will catch the eye of theshogun and have his child, thus weakening the position of the rival faction ofwomen headed by Osume (Naoko Kubo). However, the shogun prefers the maid thatFusa brought with her instead, Omino (Junko Fuji). But when Osume gets pregnantfirst, Omino conspires with Okon’s senior attendant Matsushima (Isuzu Yamada)to get pregnant secretly by another man and claim that it’s the shogun’s child…

Kyoko Kishida (left) and Tomoko Ogawa

Kyoko Kishida (left) and Tomoko Ogawa

In the second story, the shogun has his eye on the innocentShinonoi (Tomoko Ogawa) for his next bed partner, but she enters into a lesbianrelationship with her mistress, Urao (Kyoko Kishida, in another lesbian roleafter Manji). But Shininoi has nochoice but to obey when summoned to the shogun’s boudoir, which leads Urao tobecome dangerously jealous…

Kaneko Iwasaki (lying) and Yoshiko Sakuma

Kaneko Iwasaki (lying) and Yoshiko Sakuma

In the third story, Ochise (Yoshiko Sakuma), a maid to seniorlady-in-waiting Asukai (Kaneko Iwasaki), is about to finish her three years ofindentured servitude, after which she plans to leave the castle and marryfabric dyer Chokichi (Kunio Murai). No prizes for guessing what happens whenshe too catches the eye of the lustful shogun…

Kunio Murai and Yoshiko Sakuma

Kunio Murai and Yoshiko Sakuma

This Toei production was based on an original screenplay with fourcontributors, none of whom are especially well-known. Its director, SadaoNakajima, started out as an assistant director around 1959 at Toei’s Kyotostudios – which meant that most of the films he worked on early on had period settings –before directing his first film, FemaleNinja Magic, in 1964. With this debut, he (together with Kyoto studio headShigeru Okada) was responsible for introducing a new eroticism to the jidaigeki (costume drama) genre,something which is also in evidence in TheShogun and His Mistresses. Although these films were classified as ‘for adultsonly’ at the time, it should be noted that they were not pornographic, thoughother filmmakers would copy the template and add nudity and more explicit sexscenes in the years to come. As is often the case, Nakajima’s career was moreschizophrenic than that of many directors in the West, and went on to encompassa wide range of material from yakuza flicks and sex documentaries to morehighbrow (or at least middlebrow) period dramas. His Meiko Kaji vehicle Jeans Blues: No Future (1974) has aminor cult following, while his passion project The Seburi Story (1985) was nominated for the Golden Bear at theBerlin Film Festival. Nakajima’s career as a feature film director ended in thelate 1990s, but not quite – he can be seen playing the part of a director atToei Kyoto studios (much like himself) in UzumasaLimelight (2014) and returned to the director’s chair one last time at theage of 84 for Love’s Twisting Path(2018) before passing away in 2023.

The most striking direction in this film occurs towards the end ofthe first story, when Omino arrives at the secluded house with the aim of beingimpregnated by a stranger and we hear the cries of the cicadas reaching feverpitch on the soundtrack before we get a POV shot from the bottom of a well downwhich the old lady who owns the house drops her bucket. No other scene is quiteas memorable, but it’s a strong film overall, although not without itstechnical flaws – the wire attached to a fake firefly is visible at one point,while more depth of focus would have been preferable in some scenes, when theactors in the background are reduced to blurry blobs.

Tomoko Ogawa and a blurry Kishida

Tomoko Ogawa and a blurry Kishida

But these niggles aremore than made up for by the quality cast, excellent score by Hajime Kaburagi(which utilises traditional instruments to great effect) and the fact that,with all the colourful kimono on display, this is exactly the type of film thatbenefits most from colour cinematography. The film was a huge hit, which notonly spawned two sequels directed by Nakajima, but created a whole new subgenreof female-oriented jidaigeki whichcame to be known in Japan as ‘Ooku’ (inner palace) stories and would include thepreviously reviewed Tales of the Inner Chambers.

Bonus trivia:

Most of the young actresses featured in the film had never wornthe type of kimono known as uchikakebefore, so jidaigeki veteran IsuzuYamada (on loan from Toho) had to spend half a day training them how to walkwithout falling over.

Director Tadashi Imai was originally attached to the project, but hisreluctance to emphasise the erotic aspects of the story led to him being takenoff it by studio head Shigeru Okada.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

May 11, 2025

Yaneura no onna tachi / 屋根裏の女たち (‘Women in the Attic’, 1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #187

Yuko Mochizuki

Yuko Mochizuki

Residingin a small seaside town in which fishing is the main industry, Okin (YukoMochizuki) is a single mother with a modest noodle restaurant where business isslow, so she hires former stripper Harumi (Mayumi Kurata) to serve the customersand keep them entertained, successfully increasing the number of male puntersas a result.

However, Okin has an innocent teenage daughter, Oko (YasukoKawakami), who is about to graduate from high school and comes home one day tofind her mother has gone to the shops and Harumi is upstairs having sex with aman. When Okin finds out, Harumi confesses that she had taken money from theman and offers to split it with her. Being a pragmatic woman who knows anopportunity when she sees one, Okin soon dismisses her qualms and it’s not longbefore she has half a dozen prostitutes living upstairs and noodles have becomea mere afterthought.

Eachof the women has their own sad story, including Mary (a young Kyoko ‘Woman inthe Dunes’ Kishida), who has been separated from the child she had by anAfrican-American G.I. Meanwhile, Oko attracts the attention of Kawai ((EijiFunakoshi), a seemingly nice guy who gives her a lift on his bike one day onlyto take her into a secluded spot and rape her…

ThisDaiei production is a well-made and mostly well-acted film which deservesrecognition for dealing frankly with some controversial matters. It’s surely nocoincidence that, like Mizoguchi’s Streetof Shame and Kawashima’s SuzakiParadise: Red Light District, it appeared in 1956 when the question ofprostitution was a hot topic in Japan (it was finally outlawed the followingyear, five years after the American occupation ended).

Women in the Attic suffers from a number of flaws – someplot threads are left frustratingly unresolved, while the transformations of bothOkin from noodle woman to brothel-keeper and Kawai from nice guy to rapist aretoo abrupt to be fully convincing. There’s also, yet again, the misogynistcliché of a woman falling in love with her rapist – an unexpected elementconsidering that the film was based on a novel published in 1950 by femaleauthor Sakae Tsuboi, who had also written Twenty-FourEyes and provided the source story forFive Sisters (1954). However, it’s entirely possible that this was aninvention of director Keigo Kimura and his co-adaptor, Toshiro Ide and, to befair, this unfortunate aspect is somewhat balanced out by a scene in which Harumiconfronts Kawai and slaps him so hard she nearly takes his face off.

Anotherpoint that bothered me is the following: Okin’s motivation for her new businessventure is supposedly to give Oko a better life by being able to pay for her tohave classes in ikebana and dressmaking, and thereby find a good husband. Ofcourse, it’s no surprise that Oko is the one she ends up hurting the most, but theexplanation given for this is that Kawai won’t marry her because she’s thedaughter of a madam, whereas it seems clear from what we’ve seen of him thatthis is just an excuse on his part and that he’s simply a louse who would neverhave married her anyway. But perhaps I’m nitpicking too much – these misgivingsaside, this certainly remains an interesting film worth seeing, partly for itsrefusal to vilify Okin, opting instead to portray her as a well-meaning but unfortunateand rather foolish woman.

YukoMochizuki, the unlikely star of this film, may have lacked film star looks butwas a consummate actress who won awards for her roles in Kinoshita’s A Japanese Tragedy (1953), Naruse’s Late Chrysanthemums (1954) and Imai’s The Rice People (1957). A socialist, shelater became a politician and even directed three films (with running times of 40-50minutes): Umi o wataru yujo (‘FriendshipAcross the Sea’, 1960) about children being repatriated to Korea; Onaji taiyo no shita de (‘Under the SameSun’, 1962) which dealt with the discrimination suffered by mixed-race children;and Koko ni ikeru (‘Living Here’,1962), a documentary commissioned by the All Japan Liberal Labour Union portrayingthe daily lives of labourers and their families (see https://www.repre.org/repre/vol44/topics/tatsumi/).

Thanks to A.K.

Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

May 6, 2025

Dedication of the Great Buddha / 大佛開眼 / Daibutsu kaigen (1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #186

Kazuo Hasegawa and Machiko Kyo

Kazuo Hasegawa and Machiko KyoNara, the then-capitalof Japan, in the year 745. Kunihito (Kazuo Hasegawa) is a sculptor of raretalent. One day, after completing a huge sand sculpture by a river, he is upsetwhen the oblivious Mayame (Machiko Kyo) walks over it to fetch water. Anargument ensues in which they throw water at each other before going theirseparate ways. Sometime later, Mayame’s dancing attracts the attention of thelecherous Ogusu (Kenjiro Uemura), who follows her into the forest and tries torape her, but she’s saved in the nick of time by Kunihito, who happened to bepassing by. As a result, she immediately falls in love with Kunihito and becomes hisgirlfriend.

Kunihito is recruitedby the hunchbacked Kimimaro (Eitaro Ozawa, in a rare sympathetic role), who hasbeen tasked with constructing a huge statue of the Great Buddha at Kinsho-ji (nowTodai-ji) Temple and needs an assistant. Later, when Lady Sakuyako (MitsukoMito) sees some of Kunihiko’s work, she insists that he make a statue of her.Mayame, jealous of all the attention Kunihito is paying to both projects,decides to get revenge by sabotaging the Buddha statue…

This Daiei productionwas based on a play by Hideo Nagata (1885-1949) first published in 1921.Mizoguchi’s The Love of Sumako theActress (1947) had also been based on a Nagata play and, in fact, even featuredTomo’o Nagai in a small role as Nagata himself. I don’t know how it compares tothe original, but Ryuichiro Yagi’s screenplay seems, frankly, rather ludicrous,so it’s no surprise that Yagi failed to have a very successful career as ascreenwriter despite being a respected playwright himself.

Presumably, havinghappened in the distant past, the actual personalities surrounding the constructionof the Great Buddha are a bit of a mystery, but I’m willing to bet they didn’t includea vain and silly woman who spends most of her time dancing around a forest and mooningafter a sculptor. Machiko Kyo does her best, but this may well be the worstrole of her career. A lot of scenes feel too drawn-out, especially thosefeaturing Kyo blubbering, of which there are many. Such sentimental nonsensemust have seemed out of date even in 1952 and is not helped any by Ikuma Dan’s clichédscore. Intended as prestige production and optimistically submitted to Japan’sFestival of the Arts as well as Cannes, it deservedly won nothing, but luckily directorTeinosuke Kinugasa, together with stars Kazuo Hasegawa and Machiko Kyo redeemedthemselves with the following year’s far superior Gate of Hell.

May 3, 2025

The Tragedy of Bushido / 武士道無残 / Bushido muzan (1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #185

Miki Mori

Miki MoriThis Shochiku productionopens with the legend, ‘There was a time when ritual suicide, upon the death ofa feudal lord, was glorified as a gesture of loyalty inthe name of Bushido’ followed by a shot of a desert-like landscape. A smallfigure appears on the horizon and begins running towards the camera, which thencuts to a close-up of the same figure – a young samurai running frantically infear for his life. The camera then reveals he is being pursued by six men, whochase him up a steep sand dune. From a distance, we see them gaining on himuntil finally they cut him down.

This is a visuallystriking opening scene which grabs the attention immediately, partly due to theunusual setting, which doesn’t look like Japan, but must have been filmed atthe Tottori Sand Dunes, located on the north coast of western Honshu, Japan’smain island. There’s no real reason given in the script to justify the use ofthis location, but it emphasizes most effectively the hostility of the world we are about toenter.

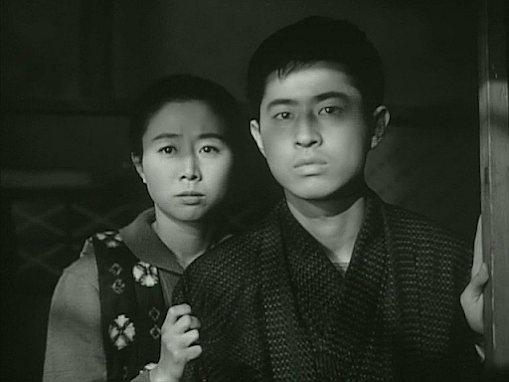

Junichiro Yamashita and Miki Mori

Junichiro Yamashita and Miki Mori

The remainder of thebrisk 74-minute film concerns Lord Nobuyuki (Miki Mori), his wife O-Ko (HizuruTakachiho) and his younger brother, Iori (Junichiro Yamashita), who are membersof the Honda clan. After the death of the clan’s leader, Noboyuki is summonedby the chief retainer (Fumio Watanabe) and informed that Iori has been selectedto perform ritual suicide in five days’ time as they need someone to followtheir late lord in death. Noboyuki has precisely zero choice in the matter, andit is up to him to inform Iori, who is only 16 years old. O-Ko is especiallydistraught as she has raised Iori as if he were her son. Accepting that shecan’t save his life, she makes the astonishing request that she be permitted tosleep with him so that at least he won’t have to die as a virgin…

Dealing as it does withthe merciless inflexibility of the code of Bushido, all-too frequently appliedin a way that resulted in the suffering of the lower ranking samurai whileenabling the higher-ranking to escape responsibility, The Tragedy of Bushido (whose title could also be translated as‘The Cruelty of Bushido’) has a great deal in common with Masaki Kobayashi’slater Harakiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967), so it’ssurprising to find that a little-known filmmaker had made such an effectivefilm on this topic as early as 1960. The filmmaker in question was Eitaro Morikawa(1931-96), who directed this film from his own original screenplay. Apparently,it was planned as Shochiku’s first ‘new wave period drama’. Morikawa had workedas an assistant director, mainly under Tatsuo Osone, but he had no previouscredits as either screenwriter or director. Given the quality of this debut, one can only assume that he did something to incur the wrath of the studioheads at Shochiku* – he never directed again, and his only other credits are asco-screenwriter on three films for Nikkatsu and one for Toei between 1963 and1966, one assistant director credit on Nagisa Oshima’s obscure 44-minute film A Small Child’s First Adventure (1963)and as a ‘planner’ on Kaneto Shindo’s Blackboard(1986). Morikawa had apparently been a classmate of Oshima’s and, after leavingthe film industry, went on to work for the Dentsu advertising agency beforebecoming a university professor.

Morikawa is ablyabetted by the high contrast cinematography of Takao Kawarazaki and unusualmusic score by Riichiro Manabe, while the non-starry cast are also effective(incidentally, Miki Mori died at the age of 26 from gas poisoning four daysafter the film’s release – a result of a leak rather than suicide, I think). Perhapsthere’s a twist too many at the end, which is the only point at which the musicgoes a little overboard, but nevertheless this gem is an impressive debut whichshould have led to a long career for its writer-director.

* Miguel Patricio hasmore to say on the abrupt end to Morikawa’s career in his review (inPortuguese) here.

Thanks to A.K.

English subtitles at Open Subtitles

April 27, 2025

The Woman Who Touched Legs / 足にさわった女 / Ashi ni sawatta onna (1952 and 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #183 and #184

Fubiki Koshiji

Fubiki Koshiji

Machiko Kyo

Machiko Kyo

Theromantic comedy Ashi ni sawatta onnabegan life as a magazine serial by the now-forgotten Nadematsu (or Nadeshiko? or Bumatsu?)Sawada (male, 1871-1927) and was first filmed in 1926 (the year of publication)by director Yutaka Abe. The story (in the two existing film versions anyway) tells of Saya, a pickpocket in Osaka who usesher good looks to get close to men in order to steal their wallets. She’s justserved three months in prison and is on her way by train back to her homevillage for the first time in many years. However, she’s not the usual criminaltype, and it emerges that her father was suspected of being a spy and committedsuicide, so she has been stealing in order to hold an expensive memorialservice for him and thereby get revenge on the villagers who ostracised him.Also on the train are Saya’s grown-up but childlike younger brother, a bumblingdetective (who previously arrested Saya but is now on vacation), and apretentious, slightly-effeminate best-selling crime writer who learns aboutSaya and wants to use her as the basis for his next novel.

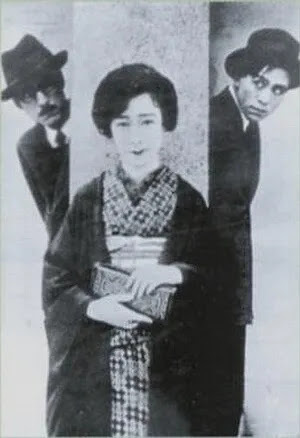

Tokihiko Okada, Yoko Umemura and Koji Shima

Tokihiko Okada, Yoko Umemura and Koji ShimaIn the 1926 film – which won the first ever Kinema Junpo Award for Best Japanese Film – the leading roles of the female pickpocket, the crime writer and the detective were played, respectively, by Yoko Umemura, Tokihiko Okada and future director Koji Shima. The former two died tragically young – Yoko Umemura (a favourite of director Kenji Mizoguchi) died at 40 following complications from appendicitis while working on Mizoguchi’s Danjuro Sandai (1944); Tokihiko Okada (the father of Mariko Okada) died at 30 from tuberculosis in 1934. Like the vast majority of Japanese silent films, that version is long lost and it’s unlikely that it still existed when Kon Ichikawa made the first remake for Toho in 1952, although he may well have seen it in his youth. Incidentally, according to Donald Richie in A Hundred Years of Japanese Film, rather than featuring a motley bunch of characters and having the bulk of the story set on a train, ‘The original Abe movie was about the upper-middle class in a hot spring resort.’ When he made the film, Abe had actually not long returned from a decade in America, during which time he had acted in a number of Hollywood films, so there’s little doubt that his work was heavily influenced by this experience.

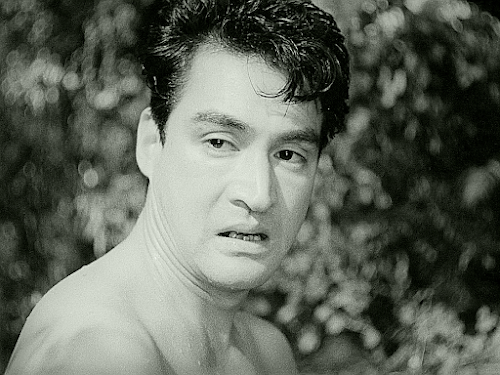

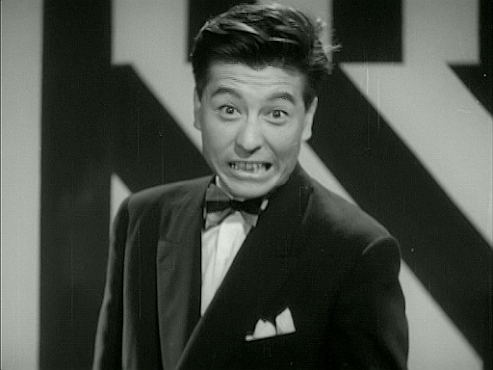

Ryo Ikebe

Ryo IkebeIchikawamodelled his version on Hollywood’s screwball comedies of the 1930s, and top-billedRyo Ikebe as the detective appears to be attempting to emulate Cary Grant. It’scertainly the most animated I’ve ever seen Ikebe on screen, but not his mostsuccessful performance in my view. On the other hand, Fubuki Koshiji, who playsSaya, is a natural comedienne and is in her element here. It’s a littlesurprising to see So Yamamura mincing his way through his performance as thepresumably gay writer, but he stops short of full-on caricature, thankfully. Onenice touch is that his character’s niece is played by Mariko Okada, whosefather had played Yamamura’s role in the 1926 original.

So Yamamura and Mariko Okada

So Yamamura and Mariko Okada

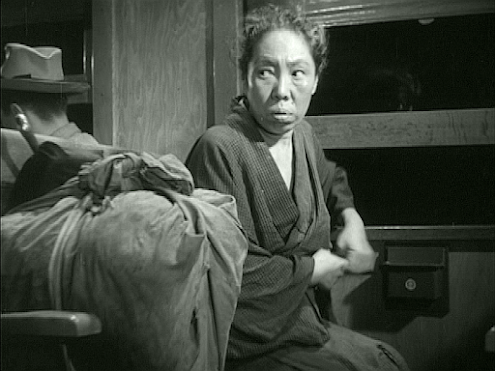

Sadako Sawamura and Yunosuke Ito

Sadako Sawamura and Yunosuke Ito Eiko Miyoshi

Eiko MiyoshiA terrific supportingcast also features Yunosuke ‘why the long face?’ Ito, Sadako Sawamura,Sawamura’s brother Daisuke Kato and ex-husband Kamatari Fujiwara, and decrepitold lady specialist Eiko Miyoshi. It’s a jolly ride which zips by in afast-paced and entertaining fashion, although some of the one-liners were nodoubt lost in the subtitles I auto-translated from Japanese.

Kyo with Hajime Hana

Kyo with Hajime HanaDaieiproduced a colour remake a mere eight years later, directed by Yasuzo Masumura.Although Kon Ichikawa and his wife Natto Wada are again credited with thescreenplay, it appears to have been revised – whether by Ichikawa and Wada orby Masumura I have no idea, but in neither version does the story make a greatdeal of sense. In any case, the 1960 version seems more calculated as a vehiclefor a particular star – in this case, Machiko Kyo, who plays Saya in a moreblatantly sexy manner than Fubuki Koshiji, although she’s arguably less of anatural for comedy. The detective is played as a much more slow-witted characterby the far less well-known Hajime Hana, but I found him more amusing than RyoIkebe, while Eiji Funakoshi is slightly less effeminate as the writer than SoYamamura had been.

Jiro Tamiya and Eiji Funakoshi

Jiro Tamiya and Eiji Funakoshi

Shiro Otsuji, Kyo and Haruko Sugimura

Shiro Otsuji, Kyo and Haruko SugimuraOther notables in the cast include Haruko Sugimura in therole formerly played by Sadako Sawamura, and Jiro Tamiya and Kyoko Enami makingearly appearances in minor roles. Perhaps the most notable difference is thatMasumura puts far less emphasis on Saya’s motivation for being a thief and, infact, drops the memorial ceremony scene entirely – the cynical Masumura wouldprobably have considered this mere sentimentality. Personally, I wouldn’tconsider either version a must-see, but I slightly preferred Ichikawa’s on thewhole. He was obviously into it anyway, as he also directed a 45-minute TVversion in 1960 with Keiko Kishi as Saya, Frankie Sakai as the detective andTomo’o Nagai as the writer.

Noteon the title:

The original novel and1926 film have a slightly different title from the remakes: Ashi ni sa hatta onna (足にさはった女), which could be translated as The Woman with a Scar on Her Leg. Although the remakes are usuallyreferred to in English as The Woman Who Touched Legs (or similar), the 1952 version at some point had the English title of DoubledyedDetective, while the 1960 versionhas also been known as A Lady Pickpocketin English. Furthermore, it’s not entirely clear what is meant by the Japanesetitle. Ashi can mean leg, legs, footor feet and, as there are no articles or possessive pronouns in Japanese, it’sanyone’s guess whether it should be ‘her leg/foot’, ‘the leg/foot’, ‘a leg/foot’,‘his leg/foot’, ‘their legs/feet’, etc. While it might be necessary to touchsomebody else’s leg when stealing a wallet from their trouser pocket, I thinkthe title is intended to refer to Saya’s legs – which she uses to attract men inorder to get close enough to pick their pockets – rather than those of hervictims, so The Woman Who Used Her Legswould seem a better title.

Thanks to A.K.

1952 version DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

April 19, 2025

Kiri to kage / 霧と影 (‘Fog and Shadow’, 1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #182

Tetsuro Tanba

Tetsuro TanbaWhen Kasahara, a teacher from the local school is found dead atthe bottom of a cliff on the Noto Peninsula, it’s assumed that he eitherslipped or committed suicide. However, his old friend Komiya (Tetsuro Tanba),who works as a reporter in Tokyo, smells a rat – he knows that Kasahara wasafraid of heights, so he decides to investigate. In the process, he uncovers acomplex (but not terribly interesting) web of conspiracy and corruption…

This Toei production features the type of story more usuallyassociated with Seicho Matsumoto, but which in this case is actually based on a1959 novel of the same name by Tsutomu Minakami (or Mizukami), known for Bamboo Dolls of Echizen, The Temple of Wild Geese, and Straits of Hunger among others. TheMatsumoto resemblance is no coincidence as Minakami himself said that he hadbeen inspired to write the book after reading Matsumoto’s Points and Lines (also known in English as Tokyo Express). It was Minakami’s first big success as a writer,and he soon proved that he was more than a mere Matsumoto imitator. Accordingto Japanese Wikipedia, a critic named Kazushi Shinoda admired Kiri to kage for portraying the ‘anguishof a man cursed by fate, and the depth of the karma of a man who tries toescape his fate but ultimately cannot’.

It’s a pity, then, that this aspect of the work is absent fromTeruo Ishii’s film, which is strictly B-movie stuff. It has been said thatIshii repeatedly attempted to make Naruse-like dramas early in his career, butthese projects were all rejected. He later became a cult director, perhapsmainly due to his willingness to make exploitation films with titles such as Horrors of Malformed Men and Inferno of Torture. Kiri tokage is well-shot but largely routine apart from the odd eccentric touchsuch as giving one of Komiya’s fellow reporters the gross habit of picking hisnose with his pencil.

Despite a reputation for turning up late on set without havinglearned his lines (and often using cue cards), Tetsuro Tanba was a fine actor, but theearly leading role he gets here is the type in which the main thing the actor has to do is simply to find adifferent way to look surprised each time they receive new information. Theremainder of the cast are not especially notable, and Chuji Kinoshita’sunsubtle music score does not help matters either, so I have to mark this onedown as another disappointment. If it’s karmic anguish you’re after, watch TomuUchida’s adaptation of Minakami’s Straitsof Hunger (better-known in English as AFugitive from the Past) instead.

Watched with dodgy subtitles (I auto-translated from Japanese).

April 17, 2025

The Hidden Profile / 風の視線 / Kaze no shisen (‘Gaze of the Wind’, 1963)

Obscure Japanese Film #181

Shima Iwashita

Shima Iwashita Keisuke Sonoi

Keisuke SonoiNatsui (Keisuke Sonoi)is a photographer who has just entered into an arranged marriage with Chikako(Shima Iwashita). Their honeymoon is an awkward flop, but during the tripNatsui discovers the body of a suicide victim, grabs his camera and snaps awaywith ghoulish gusto. He later uses thephotos in an exhibition which is a big hit.

Michiyo Aratama

Michiyo Aratama

Akira Yamanouchi

Akira Yamanouchi

Natsui is actually inlove with Ayako (Michiyo Aratama), but not only is she married to the mostly-absentShigetaka (Akira Yamanouchi), but she’s in love with Kuze (Keiji Sada), withwhom she’s having an affair, and who is also married and having an affair with a clingy bar hostess. It graduallyemerges that Ayako was the one who arranged the marriage between Natsui andChikako, partly to get Natsui to stop pestering her, but also because she knewthat Chikako was having an affair with Shigetaka …

Perhaps it wassomebody’s sly joke that this adaptation of a 1961 novel by Japan’sbest-selling mystery writer Seicho Matsumoto begins with the discovery of abody but turns out to be a romantic drama rather than a crime story. A Shochikuproduction directed by Yoshiro Kawazu, who made the previously-reviewed Eyes of a Child (1955), it also featuresa rather stiff cameo by Seicho Matsumoto himself as a writer Kuze runs into ina bar.

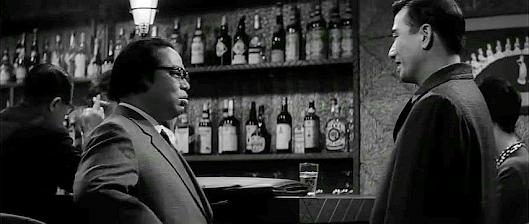

Seicho Matsumoto and Keiji Sada

Seicho Matsumoto and Keiji Sada

The plot features a coupleof unlikely and fairly pointless coincidences and in this case the level ofsuspense is mild to say the least. Despite a promising cast, nobody gets achance to do their best work here, while composer Chuji Kinoshita simply seizesthe opportunity to follow in the footsteps of Toshiro Mayuzumi and Sei Ikenoand experiment with a musical saw for no good reason. A story concerning such abizarre web of intertwined relationships might have worked as a farcical blackcomedy, but the film takes itself far too seriously and plods leadenly on toits contrived conclusion, making it hard to regard it as anything other than a competentfailure.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

English subtitles courtesy of Coralsundy can be found here.

April 12, 2025

Wandering Shore / 流離の岸 / Ryuri no kishi (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #180

Terumi Niki

Terumi Niki Sachiko Murase

Sachiko MuraseChiho (Terumi Niki) isa young child left alone in the country to be raised by her grandmother , Uta (SachikoMurase), because her mother, Hagiyo (Nobuko Otowa), has left her father and isgetting remarried. Chiho is a sensitive but also somewhat wilful and proudchild who misses her mother but doesn’t like to admit it. Uta sends Chiho totake food to her neighbour, Okichi (Sachiko Soma), whom Uta has known sincechildhood. Uta is now a penniless old lady living in a shack; according to Uta,she has ended up this way because she was frivolous in her relationships withmen and spent her life doing what she wanted without regard for theconsequences.

After a year, Chihogoes to live with her mother and stepfather, Takakura (Nobuo Kaneko), who has ason of his own, but Chiho’s status is lower and she feels it. Ten years pass,and Chiho (now played by Mie Kitahara) is a high school student living with heruncle (Taiji Tonoyama) and his wife (Yoshiko Tsubouchi). When Chiho wakes up one day with astrange pain in her finger, she goes to see her friend’s father, a doctor, buthe’s out, so the doctor’s son, a newly graduated medical student, Ryukichi(Rentaro Mikuni), attends to her instead. An instant mutual attraction soonleads to marriage plans, but Ryukichi has not been entirely honest with herabout his past…

Released four monthsafter Love is Lost (see reviewbelow), this is another Nikkatsu production written and directed by KanetoShindo and featuring some of the same cast, with Nobuko Otowa taking asupporting role here and Taiji Tonoyama and Jun Hamamura popping up as expected.Again, the screenplay was not an original – in this case it’s an adaptation ofa novel first published in 1953 by Yoko Ota (1906-63),* whose childhood seemsto have been similar to that of Chiho’s.

The film is a littleless successful than Love is Lost – althoughit also features the work of composer Akira Ifukube and cinematographer TakeoIto, their contributions here are less memorable. For his part, Shindo wasperhaps a little too faithful to the novel as the story feels more complicatedthan it needed to be. However, while Terumi Niki (from the previous year’s Policeman’s Diary) growing up to be MieKitahara is a stretch, the attraction between Chiho and Ryukichi is convincing.The film is also quite powerful in putting across its message, which I wouldsummarise as a cautionary one about the irreparable damage that can be causedto a relationship when one party deceives the other – especially when thatother is a sensitive soul like Chiho, whose fractured childhood has left her moreemotionally vulnerable than most.

*Ota was a Hiroshimasurvivor and her 1948 novel City ofCorpses on this theme is available in English translation in Hiroshima: Three Witnesses (PrincetonUniversity Press, 1990). She also has a short story in the collection Fire from the Ashes: Short Stories aboutHiroshima and Nagasaki (Readers International, 1985).

Thanks to A.K.

April 10, 2025

Love is Lost / 銀心中 / Gin shinju (‘Silver Double Suicide’, 1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #179

Jukichi Uno and Nobuko Otowa

Jukichi Uno and Nobuko OtowaTokyo, c. 1942. Sakie (Nobuko Otowa) and her husband Kiichi(Jukichi Uno) run a barbershop together and agree to take Kiichi’s nephewJutaro (Hiroyuki Nagato) as a live-in apprentice. When Kiichi is called up tojoin the army, his absence brings Sakie and Jutaro closer during his absence,but it’s not long before Jutaro is also conscripted. One day, a messengerarrives to inform Sakie that her husband has been killed in battle in the Philippines.After living out the remainder of the war with her brother (Akitake Kono) andhis resentful wife (Harue Tone) in the country, Sakie returns to Tokyo to findthe barbershop in ruins, but is reunited with Jutaro. Their relationship soonturns romantic and they vow to rebuild the business, but the course of truelove never runs smooth…

This Nikkatsu production was based on a 1952 short story of thesame title by Torahiko Tamiya (male, 1911-88), whose work also provided thebasis for Miyoji Ieki’s Stepbrothers (1957)among other films. Written and directed by Kaneto Shindo, as usual it stars hislong-term mistress, Nobuko Otowa, who gives a typically fine performance in thelead role. The rest of the cast also acquit themselves well and it’s alwaysgood to see Shindo’s stock company of his favourite character actors, including Taiji Tonoyama,Tanie Kitabayashi and – very briefly as a barbershop customer – Jun Hamamura. However,I did think that the actress playing Umeko, the alcoholic, gambling-addictedharlot went way over the top – I finally realised that this role was also beingplayed by Nobuko Otowa! This is cleverly shot and edited, with Taiji Tonoyamaplaying a scene with both Otowas.

Taiji Tonoyama with Otowa as Sakie

Taiji Tonoyama with Otowa as Sakie

TT with Otowa as Umeko

TT with Otowa as Umeko

This film has its flaws and gets a bit too repetitive in itslatter stages, with virtually the same scene playing out several times, and itwould be easy to dismiss it as just another rather hokey tragic love story. However, it alsoprovides a powerful depiction of the sense of futility and waste that theJapanese felt after the war, and how this inevitably led to widespreaddisillusionment, bitterness, cynicism and nihilism. In one scene which has no bearing onthe plot, the bombed-out Sakie and Jutaro take shelter with othernewly-homeless Tokyo residents in the subway and look on as two men chase ascreaming woman through a tunnel. Nobody intervenes or even offers a comment.For me, this type of seemingly-irrelevant scene which actually speaks volumesis the mark of a great filmmaking talent, which I think Shindo certainly was. Theexcellent cinematography of Takeo Ito (an award-winner for Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel) and score by Godzilla composer Akira Ifukube alsohelp to make this a film worth seeking out.

Thanks to A.K.

On Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)