M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 2

August 18, 2025

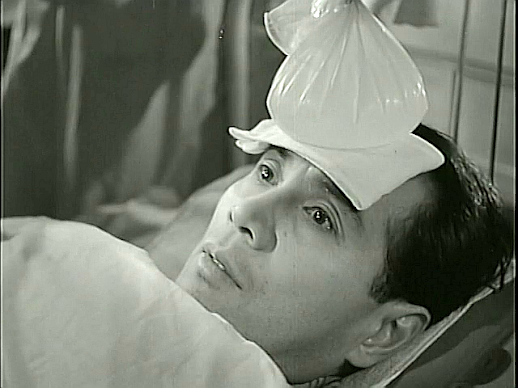

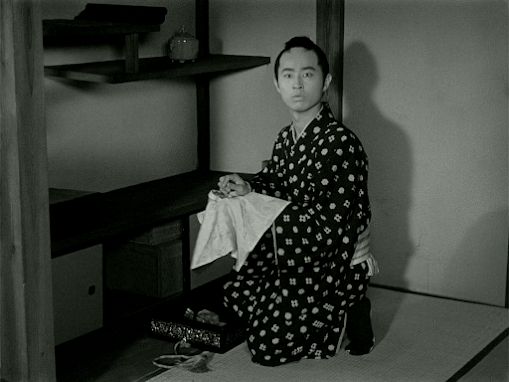

Yume miru hitobito / 夢見る人々 (‘People Who Dream’, 1953)

Yoko Katsuragi

Yoko Katsuragi Shinya (Masao Wakahara)is an architect who returns home from ‘the South’ for the first time since thewar to find that his fiancée, writer Yuriko (Mieko Takamine) has marriedsomeone else, his family home has been destroyed in an air raid and his parentskilled, and his half-sister and her husband have spent his inheritance.Needless to say, he’s not a happy bunny. However, his father’s friend’s granddaughter,Sumiko (Yoko Katsuragi), still loves him even though he only thinks of her as ayounger sister…

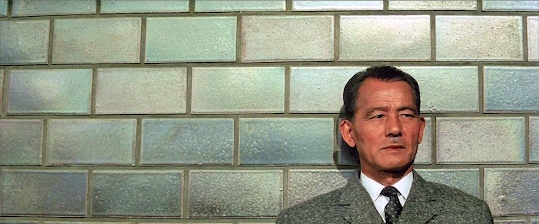

Masao Wakahara

Masao WakaharaThis Shochiku productionwas based on a 1952 newspaper-serial novel by Nobuko Yoshiya, theChristian-lesbian writer who also supplied the source material for Flower-Picking Diary (1939). In thiscase there’s no sign of Christianity nor lesbian love, and the two moreunconventional female characters – company president Fujie (Sadako Sawamura)and her tomboyish daughter Ioko (Kyoko Kami) – seem to be present mainly toserve as comedy relief. Speaking of comedy, one amusing moment which feelsunintentional comes at the beginning when a blind war veteran solicitsdonations on a train and seems able to tell when people are holding out moneyto him even when they say nothing.

Kyoko Kami, Wakahara and Sadako Sawamura

Kyoko Kami, Wakahara and Sadako SawamuraThe awkward subject ofthe war is always present in the background of the story, but only occasionallycomes to the fore, and it’s entirely unclear what Shinya has been doing for theseven or eight years since the conflict ended. We know only that he hastestified on behalf of a former sergeant, Arakawa (Jun Tatara), to save himfrom being sentenced as a war criminal. Many of the characters are portrayed asvictims of the war in various ways, and there’s never really an acknowledgementof any guilt – the closest we get is a scene in which Shinya’s father’s friend,Shibata (Eijiro Yanagi), finally forgives his son, who had incurred his wrath during the war by daring to express the opinion that Japan would lose.

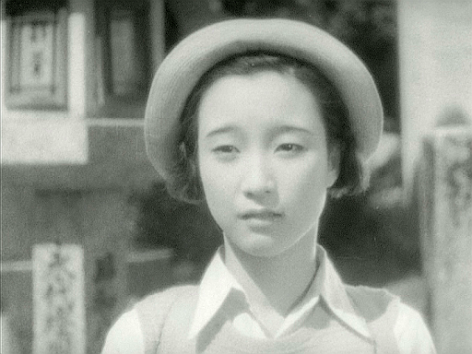

Mieko Takamine

Mieko TakamineIn terms of the cast,the forgotten Masao Wakahara as Shinya – described at one point as looking‘like (Charles) Boyer’ – seems to have been quite a big star at the time, buthis performance here is on the wooden side, which is perhaps why his career peteredout early once his Boyer-esque looks began to fade. Mieko Takamine does herbest with an underwritten role, but it’s Yoko Katsuragi as Sumiko who reallybecomes the heart of the film. She was an underrated actor whose girlish looksoften prevented her from getting the more interesting dramatic parts, but it’s notfor nothing that she was a favourite of Keisuke Kinoshita as well as thisfilm’s director, Noboru Nakamura, for whom she made six pictures. One of thesewas Nakamura’s previous film, Natsuko’s Adventure in Hokkaido, in which she had also co-starred with Masao Wakahara. Regarding Nakamura,his direction is certainly highly competent, but his best work was yet to comein films such as Koto (1963), The Shape of Night (1964) and The Kii River (1966).

Thanks to A.K.

August 14, 2025

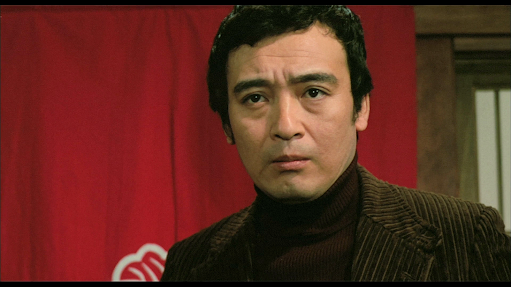

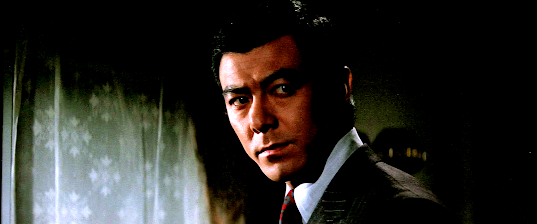

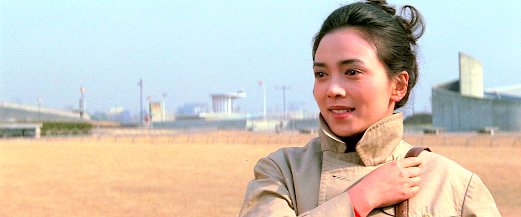

The School of Flesh / 肉体の学校 / Nikutai no gakko (1965)

Kyoko Kishida

Kyoko KishidaTaeko(Kyoko ‘Woman of the Dunes’ Kishida) is a wealthy, aristocratic and self-confidentTokyo fashion designer who visits a gay bar, where she is attracted to younger,proletarian bartender Senkichi (Tsutomu Yamazaki, the kidnapper from High and Low), whom she asks out on adate. The rumour that he’ll sleep with absolutely anyone for money fails to puther off, but she’s taken aback when he turns up wearing geta (wooden sandals), chews with his mouth open and takes her to apachinko parlour, but she soon gets over it and the two embark on arelationship. However, when her friends ask her if Senkichi is kind to her, sherealises that she can’t think of a single example of his showing such a qualityand begins to feel somewhat insecure in their relationship. But it turns outthat Senkichi is actually far more conventional than he pretends to be…

Tsutomu Yamazaki

Tsutomu YamazakiThisToho production was based on a novel of the same name by Yukio Mishima first published in 1963 in serial form in a magazine called Mademoiselle. Although it has yet to betranslated into English,* this appears to be a very faithful adaptation andMishima is on record as being highly pleased with it. The author’s obsessionwith physical beauty and the psychology of infatuation are much in evidence,but theprotagonists are both hard to like and I can’t say that I personally found the story very engaging. Most of the drama comes from the shiftingbalance of power in their relationship.

Whatreally makes this film worth seeing, however, is the striking visual style thatdirector Ryo Kinoshita (b.1931) and his cameraman Yuzuru Aizawa (who also shot The Bad Sleep Well) bring to it. Kinoshitawas a former assistant to Yuzu Kawashima (and no relation to Keisuke Kinoshitaas far as I’m aware). The rest of his brief filmography looks pretty routine, buthe was one of those directors whose career began a little too late, leaving himfew opportunities to show what he could do for the cinema before he was forcedto move into television instead. In fact, part of the reason for the move inhis case may have been that the bigwigs at Toho were, apparently, displeasedwith the arty visuals in The School ofFlesh. However, in my opinion, the use of deep focus, unusual camera anglesand bold lighting effects makes this film a visual treat throughout.

The agediscrepancy between the two characters is less pronounced than in the book,which describes Taeko as being 39 and Senkichi 21 – at the time of the film’srelease, Kishida was 34 and Yamazaki 28. The two stars had both been members ofthe Bungakuza theatre company and knew each other well. Another personassociated with Bungakuza was Yukio Mishima himself – the company had staged anumber of his plays, often featuring Kishida, an actress who was both admiredand befriended by the writer.

*Thenovel has appeared in French and also provided the basis for the French film L’ecole de la chair (1998) starringIsabelle Huppert.

Thanksto A.K.

August 11, 2025

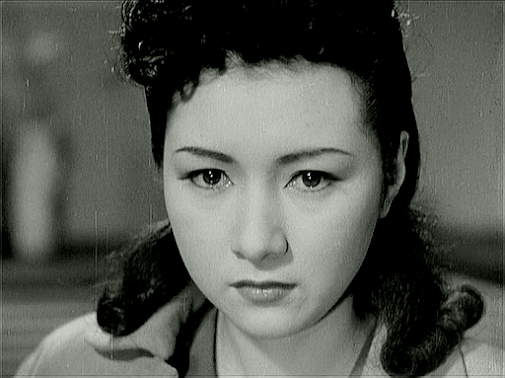

Flower-Picking Diary / 花つみ日記 / Hana-tsumi nikki (1939)

Hideko Takamine

Hideko TakamineMitsuru (MisakoShimizu) is a girl from Tokyo whose family have just moved to the Soemonchodistrict of Osaka. She’s in her early-mid teens and her mother is a Christian. Whenshe begins attending her new school, she soon becomes best-friends with classmateEiko (Hideko Takamine), who used to live in Tokyo herself when she was small.Her family have a business training maiko(apprentice geisha) to sing, dance and play instruments. When the two girlscome up with a plan to make a gift together with which to surprise their kindlyteacher (Kuniko Ashihara) on her birthday, a misunderstanding ensues and theyfall out. Both girls are miserable as a result, and Eiko gets to the pointwhere she can’t even face school anymore, so she drops out to become a maiko herself…

Produced by Toho Eigabefore they became known simply as Toho from 1943, Flower-Picking Diary was based on a story by Nobuko Yoshiya(1896-1973). Being both a Christian and a lesbian, she wrote from an unusualperspective for a Japanese author of the time, but her books were highlypopular with female students – so much so, in fact, that there had already beenaround 30 movies based on her work. The main source of this particular pictureis a story entitled ‘Tengoku to maiko’ (‘Heaven and maiko’) from her 1936 collection Chisana hanabana (LittleFlowers), but it seems that some elements may have been borrowed from otherstories by Yoshiya as the story of the film (as adapted by female screenwriterNoriko Suzuki) differs considerably. The main difference is that there isapparently no falling out between the two girls in the original – a fact Ifound quite surprising considering that this is absolutely central to the film.Indeed, the extent to which it should be interpreted as the story of a lesbianlove is debatable – there’s certainlynothing overt – but it’s certainly a film about friendship and the devastatingfeelings that can occur when two close friends fall out. It’s difficult tothink of other examples of films dealing seriously with broken friendships, butthis one is very moving once it gets going (there may be rather too muchsinging of sentimental songs in the earlier stages).

The shadow of war loomslarge over the film, and the scenes of largely unquestioning and joyfulcelebration when Mitsuru’s brother gets called up have not dated well, but arerevealing of their time. (Incidentally, Nobuko Yoshiya’s reputation suffered somewhat afterthe war as she was said to have toed the authoritarian government line a littlemore than necessary.) Ironically, though, it’s the war that gives some hope forthe future of Eiko and Mitsuru’s friendship as Eiko decides to make a senninbari for Mitsuru’s brother, whichinvolves her standing at the bridge on Shinsaibashi Street and asking passingwomen to sew a stitch to make up the 1000 needed for this type of amulet belt.

Hideko Takamine was 15when she made this, but already an old pro who had made dozens of films sinceher film debut in 1929 at the age of 5. Her co-star, Misako Shimazu, was a veryyoung-looking 20 years of age, and was featured in a few other films butdisappeared from the screen after 1941. Takamine may well have related to herrole more than usual here as, shortly before making the film, like Eiko, she hadbeen forced to leave school and pursue a career she did not particularly carefor (acting in movies was something she felt obliged to do as no less than ninefamily members were relying on her financially).

The sensitive directionis by Tamizo Ishida (1901-72), who made around 90 films between 1926 and 1947,but the only other one which is relatively easy to find in decent quality with Englishsubtitles is Fallen Blossoms (1938).

BONUS TRIVIA: If theactor playing Eiko’s father looks familiar, that’s probably because it’s EitaroShindo, who went on to play the title role in Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece Sansho Dayu (1954)

Some of the informationabove comes from a review on Amazon Japan by ‘Beautiful Summer.’

Thanks to A.K.

August 6, 2025

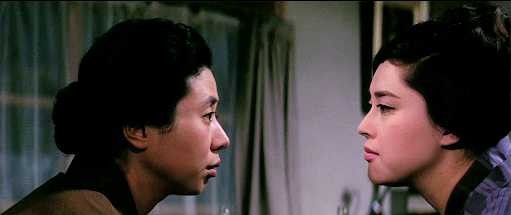

Woman Unveiled / 女であること / Onna de aru koto (‘Being a Woman’, 1958)

Yoshiko Kuga

Yoshiko Kuga

Masayuki Mori and Setsuko Hara

Masayuki Mori and Setsuko Hara

Sadatsugu (MasayukiMori), a lawyer, and his wife Ichiko (Setsuko Hara) are a childless couple whoare looking after the daughter of one of Sadatsugu’s clients, who is facing adeath sentence, though we never learn precisely what for. The daughter, namedTaeko (Kyoko Kagawa), appears to be in her late teens, and is sensitive, timidand rather gloomy, perhaps mostly due to her father’s situation.

Sadatsugu andIchiko then find themselves having to look after another young woman of asimilar age, Sakae (Yoshiko Kuga), who has run away from home and is thedaughter of Ichiko’s best friend. Unlike Taeko, Sakae turns out to be a spoilt,insensitive troublemaker with no filter and no control over her emotions. It’snot long before she’s annoying Taeko with her directness, flirting withSadatsugu and even coming home drunk and kissing Ichiko on the lips. Meanwhile,Ichiko has a chance meeting with old flame Goro (Tatsuya Mihashi), whom shehasn’t seen for 17 years. Then Sakae finds out and starts sticking her oar in…

This production by TokyoEiga (a subsidiary of Toho) was director Yuzo Kawashima’s first for them afterleaving Nikkatsu. It was based on an untranslated novel of the same name byYasunari Kawabata originally serialised in the Asahi Shinbun during 1956. Despite the fact that it’s notconsidered one of future Nobel laureate Kawabata’s most notable works,Kawashima – along with his collaborators Sumie Tanaka (female) and Toshiro Ide(male) – is said to have gone to a great deal of trouble over the screenplay.By all accounts a pretty faithful adaptation, nevertheless Kawashima apparentlyregarded the film as a failure, feeling that he had failed to make of it anymore than an illustrated version of the novel’s key scenes. It’s also likelythat some important aspects had to be implied in the film version due tocensorship – for example, that Sadatsugu and his wife haven’t slept togethermuch in their ten years of marriage, and that Ichiko’s interest in sex isrevived partly due to her kiss with Sakae and partly as a result of meetingGoro again. There’s also some suggestion that Sadatsugu sleeps with Sakae, butit’s not really made clear. However, what’s more frustrating is that we learnnothing of the crime for which Taeko’s father is facing a death sentence and,in fact, never even lay eyes on him – it’s simply a convenient device to giveher something to feel troubled about. It seems to me that the inclusion of sucha story element rather obliges the writers to expand a little (I would assumethat Kawabata went into more detail in his book).

The film opens with amontage sequence of Yoshiko Kuga shot from behind riding around on her bike andshouting out greetings to various passers-by. This is followed by Akihiro Miwa,the drag queen from Black Lizard(1968), dancing and singing the title song (i.e. ‘Being a Woman’) over theopening credits before two American military planes go roaring overhead, scaringKyoko Kagawa’s pet bird. It’s hard to know what to make of this opening – apart fromwhimsy on the part of Kawashima – as none of it seems to bear much relation towhat follows.

Though by no means abad film, Woman Unveiled alsofeatures a disappointingly corny, Hollywood-style score by Toshiro Mayuzumi andwraps things up in mostly conventional fashion, although the change undergone byKyoko Kagawa’s character is somewhat unexpected. The posters promoted SetsukoHara as the main star, but it’s Yoshiko Kuga who steals this one – theterm ‘charm offensive’ springs to mindhere, as she simultaneously manages to be both charming and offensive. Incidentally, the role is strikingly similar to theone she played in the previous year’s Banka(aka Northern Elegy), in which shealso caused trouble for a middle-aged and married professional played byMasayuki Mori. For all its flaws, WomanUnveiled remains a well-made and intelligent film arguably more in theNaruse mould than the Kawashima one (if such a thing existed) with a trio ofvery different but interesting and well-rounded female characters at its centre.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

August 2, 2025

Rats of the Town / 江戸の小鼠たち / Edo no koizumi tachi / (‘Little Rats of Edo’, 1957)

Masahiko Tsugawa

Masahiko Tsugawa

1832. Jirokichi(Masahiko Tsugawa) is an angry young man living in a tenement in Edo (nowTokyo) at a time when poverty is widespread and corruption is rife. Hisnamesake, the real-life thief Jirokichi (better-known as Nezumi Kozo, or ‘RatBoy’)* has just been executed. Like many young men, Jirokichi idolises him as asort of Robin Hood-figure who helped the poor and continually outsmarted TheMan. Unfortunately, his attempts toemulate his hero tend to cause trouble for his fellow tenement-dwellers, and hereceives no parental guidance as his mother is dead, while his father (AkitakeKono) is unemployed and gambles away what little money they have.

Izumi Ashikawa

Izumi AshikawaThe girl next door, Okin(Izumi Ashikawa), works at a teahouse and, to Jirokichi’s annoyance, is courtedby a young samurai, Kakusaburo (Hiroyuki Nagato). Jirokichi picks a fight withhim and wins, after which the two become friends. Some local yakuza whowitnessed the fight decide to employ Jirokichi. Despite the fact that he hadpreviously fought against the yakuza when he saw them ripping off the poor, he’snow happy to work for The Man as the other tenement-dwellers have come to seehim as a troublemaker and turned against him. Only Okin still believes in himas she remembers all the times he protected her when she was a young girl…

Hiroyuki Nagato

Hiroyuki NagatoThis Nikkatsuproduction was based on a then newly-published novel by Genzo Murakami, a specialistin samurai tales. The two young male stars, Masahiko Tsugawa (17) and HiroyukiNagato (23), were not only brothers, but were also both associated withso-called ‘sun tribe’ pictures – Tsugawa with Crazed Fruit and Nagato with Seasonin the Sun (both 1956). Although this film is by no means a ‘sun tribe’ jidaigeki (period drama), it’s obviousthat it was made to appeal to the youth market.

Directed by veteran TaizoFuyushima, who made Joshu karasu (seemy review for more on him), like that film, this one is very well-made andentertaining with quite a lot of humour if not a great deal of depth, and alsofeatures some excellent cinematography, in this case by Shohei Imamurafavourite Shinsaku Himeda. Transposed to another era, Jirokichi is akin to the typical nihilistic young rebel of post-war Japan who felt let down by the older generation (represented by here by his worse than useless father), but the light, conventional tone of the ending negates any impact the film might have had.

Watched with dodgy subtitles.

*This historical figurebecame the hero of various kabuki plays, novels and motion pictures in Japan;of the latter, Daisuke Ito’s Jirokichithe Rat (1931) is the most notable.

July 28, 2025

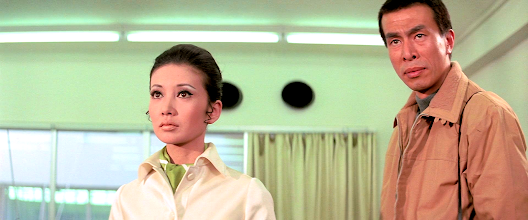

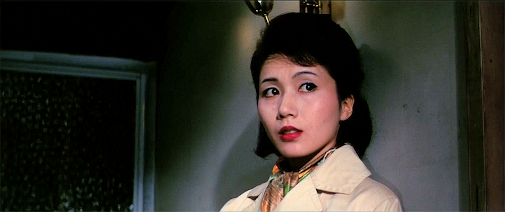

May Love Be Restored / 五番町夕霧楼 / Gobancho Yugiri-ro (1980)

Keiko Matsuzaka

Keiko Matsuzaka

A little background may be useful here, so please bear with mebefore I get to the film…

In July 1950, the famous 500-year-old golden temple known asKinkaku-ji in Kyoto was deliberately burned down by an apprentice monk named Yoken Hayashi, who made asuicide attempt immediately after but failed and was sentenced to seven yearsin prison as a result. His health worsened during his incarceration and he wasreleased early, but died in 1956 aged just 26. Kinkaku-ji was successfullyreconstructed in the intervening years and still stands today. Hayashi, who sufferedfrom a severe stutter he was said to have had since the age of 3, neverexplained the reasons for his actions.

In 1956, Yukio Mishima published his novel based on the incident(known in English as The Temple of theGolden Pavilion). Mishima interpreted the crime as the result of an urge todestroy beauty – a recurring theme in his work The novel was filmed in a compromisedversion by Kon Ichikawa in 1958 as Enjo(aka Conflagration); a morefaithful version by Yoichi Takabayashi appeared in 1976.

Another writer, Tsutomu Mizukami (or Minakami), had also becomeinterested in the story from a different perspective. Mizukami had himself begun monastic training while still a boy, but was treated badly and quit by thetime he was 18. He related to Hayashi, whom he even claimed to have metbefore the incident, and interpreted the crime as an act of rebellion againstthe hypocrisy of the temple authorities. Mizukami (who also authored The Temple of Wild Geese, another story involving a disaffected acolyte) carried out a great deal ofresearch on the case and published his own novel inspired by it, Gobancho Yugiri-ro, in 1962. Shortlybefore committing his act of arson, Hayashi was said to have visited the sameprostitute a couple of times in the red light district of Kyoto known asGobancho, and Mizukami took this detail and created a major character out ofher. In his novel, the two are childhood sweethearts from a struggling ruralcommunity who end up being sent (separately) to Kyoto by their families forvery different reasons – he to train as a monk, she to work as a prostitute ina brothel as her destitute father has too many hungry mouths to feed.

Gobancho Yugiriro was first filmed in 1963 by directorTomotoka Tasaka. In his version, the prostitute (now named Yuko) is the focusof his film, with Hayashi (now Kunugi) not appearing until quite late on. Incontrast, the version we’re concerned with here – directed by Shigeyuki Yamane andproduced by Shochiku – balances its story more equally between the two principals.This is likely because Mizukami had published a second book about theKinkaku-ji incident in 1979. Entitled Kinkaku-enjo(‘The Burning of the Golden Pavilion’), it was a non-fiction account which hasyet to be translated into English. The opening credits of this film state thatit is based on both books.

Yuko (Keiko Matsuzaka) is treated with apparent kindness by themadam, Katsue (Yuko Hama), whose brothel is named Yugiri-ro (providing thesecond half of the Japanese title). Although in neither film is this charactertreated with condemnation, she is, of course, involved in a sleazy business,and she arranges for one of her trusted regulars, the middle-aged ‘Ta-san’(Hiroyuki Nagato) to take her virginity, and he becomes sexually-obsessed withher. Once that’s out of the way, Yuko takes to her new profession withdisconcerting ease, and soon becomes the most popular prostitute in the place –with the clients, that is. Her colleagues soon get tired of being passed over andbecome envious. Meanwhile, Yuko secretly makes contact with Kunugi (EijiOkuda), the stuttering apprentice monk she had grown up with and who is theonly person she truly loves. She also feels responsible for his affliction as it began when they were children after she had accidentally dropped a snake on him while trying to get it out of a tree with a stick. He begins visiting her at the brothel, where shepays his fees, but, instead of sleeping together, they spend their time talkingand singing songs they remember from their childhood. He’s supposed to belooking after the Golden Temple (here called Hokaku-ji), but he’s becoming increasinglydisillusioned with his vocation and his relationship with the head priest (ShinSaburi) is deteriorating, while he sees little hope for a future with Yuko…

On the whole, I have to say that I prefer the 1963 version, mainlybecause I think it’s better cast and acted. Yuko is supposed to be 19 years oldwhen she enters the brothel but, despite the fact that the 27-year-old KeikoMatsuzaka has not even the suggestion of a wrinkle, she somehow fails toconvince as a teenager. However, having played leading roles in a number ofsuccessful films and TV dramas throughout the 1970s, she was a big star whosepopularity was at its peak at the time this film was released. Some of theother performances also suffer in comparison to the earlier film – Hiroyuki Nagatooverdoes it here (I preferred Minoru Chiaki in the 1963 version), while, as the madam, YukoHama is less memorable than Michiyo Kogure.

Another issue is that, although the film is set in 1950, it doesn’t always feel like it. A lot of little details don’t seem quite right – for example, thecharacter known as ‘sensei’ played by Tadashi Yokouchi wears a polo-neckedsweater and corduroy suit – was anyone really wearing that in 1950? And thecheesy music score which sometimes lapses into anachronistic distorted electricguitar doesn’t help either.

The one point on which I felt it improved on the previous film was inits portrayal of the ensemble of prostitutes who share the brothel with Yuko.In Tasaka’s film, we were given what looked like a very rose-tinted view inwhich it was basically one happy family with perfect manners and barely a hintof conflict or rivalry, whereas Yamane’s film shows the inevitable frictionbetween the women, which even erupts into a catfight at one point, and their excessivemake-up and gaudy clothes seem more fitting. But the film has little to say aboutthe burning of the temple – ultimately, it’s simply a confection intended to appeal tothose with a taste for romantic tragedies.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

July 23, 2025

The Makioka Sisters / 細雪 / Sasameyuki (‘Light Snowfall’, 1950)

Hideko Takamine

Hideko Takamine **Thefirst four paragraphs are mostly identical to those in my review of the 1959 version**

Junichiro Tanizaki’snovel Sasameyuki is widely recognisedas a classic of Japanese literature. Translated into English as The Makioka Sisters in 1957 by Edward GSeidensticker, it’s remained constantly in print ever since. The book wasoriginally published in serial form beginning in 1943, but this was soon haltedby the Japanese War Ministry – not because it criticised the government, butbecause, according to them at the time, ‘The novel goes on and on detailing thevery thing we are most supposed to be on our guard against during this periodof wartime emergency: the soft, effeminate, and grossly individualistic livesof women.’* I would have thought they should have been more worried about theenemy, but in any case, Tanizaki was forced to wait until the war had ended toresume publication, with the final instalment appearing in 1948.

The story itself takesplace between 1936 and 1941, ending around eight months before the attack onPearl Harbour, and it seems that Tanizaki’s intention was partly to provide arecord of a way of life he had seen rapidly vanishing before his eyes. TheMakioka sisters are four adult siblings whose parents are deceased. Once agrand family, their fortunes are on the wane but they remain very well-to-do incomparison with most Japanese and keep a number of servants. The eldest,Tsuruko (played here by Ranko Hanai in what amounts to a minor role), livesapart from the others with her husband and children in what is referred to asthe ‘main house.’ She is a peripheral character, but, as the senior survivingmember of the family, the other sisters must defer to her and her husbandbefore making any important decisions. Tsuruko later goes to live in Tokyo whenher husband has to relocate for his job, but her sisters remain in theirhometown of Osaka.

The other three sisterslive together. In order of age, they are Sachiko (Yukiko Todoroki, who went onto play Tsuruko in the 1959 version), Yukiko (Hisako Yamane) and Taeko,familiarly called ‘Koi-san’ (Hideko Takamine). Sachiko is married to Teinosuke(Seizaburo Kawazu), with whom she has one child, Etsuko (Takako Yamazaki).Although Sachiko is held responsible for her two younger sisters by the mainhouse, little of the drama revolves around her. Instead, much of it concernsthe attempts to find a husband for Yukiko, whose shy and sometimes stubbornnature makes this difficult. Ever since her original fiancée was killed in anaccident, each marriage proposal has come to naught for one reason or another,and Yukiko is already approaching 30 when the story begins. Complicatingmatters further is the fact that Taeko must wait until Yukiko is married beforegetting married herself in order not to humiliate Yukiko and leave her lookinglike an old maid that nobody wants. Taeko is the closest thing to a rebel inthe family, generally doing as she likes and indulged by her older sisters, whomake allowances for her due to the fact that their parents died when she was soyoung. She has a long-running on-and-off relationship with the wealthy Kei-bo (Haruo Tanaka).

The sisters arelikeable characters who live their lives trapped in a web of etiquette.Overly-concerned with what others think, they are unable to make a move withoutfirst ensuring that what they do will not offend anyone else or damage theirown social status, but there’s little in the way of arrogance about them.Rather, they are simply behaving according to the rules by which they werebrought up and it doesn’t even occur to them to do otherwise. In the book,Tanizaki paints a minutely-detailed picture of their lives, but never tells uswhat to think about it. The future of the family is left open at the end, butit’s impossible to be unaware of the dark cloud of war that awaits them justover the horizon, and no doubt Tanizaki planned it that way.

This first film versionof the novel was produced by Shintoho and is probably the most faithful of thethree overall. According to Japanese Wikipedia, it had ‘a budget of 38 millionyen, an unprecedented sum for a film at the time.’ The 1959 version updated thestory to what was then the present day, but this one retains the pre-warsetting of the book and, being around 35 minutes longer, is also able to fit alittle more in. Both the 1950s adaptations were scripted by Toshio Yasumi, whoin this one includes the dark spot on Yukiko’s face that comes and goes and issupposedly a common affliction of unmarried women (something which was droppedfrom the 1959 film).

The later version is probably the more technically (and visually) impressive of the two – here, although there is quite an impressive flood sequence, weonly hear about Koi-san’s rescue – but this one is well-done for its time andmuch superior to the one other film I’ve seen by its director, Yutaka Abe (therecently-reviewed 1956 film TheConfession). He was no flashy stylist; instead, he rightly lets the camerabe the actors’ friend here, using close-ups judiciously and tracking shots whennecessary. Another asset is the music by Kurosawa favourite Fumio Hayasaka,which is certainly one of the less grating and more effective scores of its era.

Although technically anensemble piece, this is Hideko Takamine’s film all the way, partly because hercharacter goes through the most changes and she gets the lion’s share of thescreen time, but also because she’s so photogenic and charismatic that everyoneelse seems to fade into the background when she’s in view. As Koi-san, sherejects her family’s obsession with tradition and form, deciding that a man’sactions are more important than his education or lineage – an ideology whichwould have found favour with the occupying Americans whose approval was neededfor all films produced in Japan at the time. All in all, albeit not impressiveenough to qualify as a masterpiece, this is at least a fine version of aliterary classic, with a great star at its centre, and as such it deserves tobe restored and more widely seen.

Bonus trivia: Futurestar Kyoko Kagawa appears briefly in one of her first roles as Itakura’ssister.

Thanks to A.K.

July 20, 2025

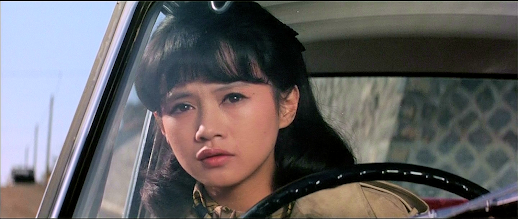

Ai no kaseki / 愛の化石 (‘Fossil of Love’, 1970)

Ruriko Asaoka

Ruriko Asaoka

Yuki (Ruriko Asaoka) isa textile designer who has studied in Europe and become a big success on herreturn to Japan. It probably doesn’t hurt that she looks more like a model thana designer and seems to have an inexhaustible supply of à la mode outfits.Perhaps that’s why magazine journalist Junko (Mayumi Nagisa) thinks she’d makea good subject for an article and assigns her hotshot photographer boyfriendHibino (Etsushi Takahashi) to do the pictures.

Mayumi Nagisa

Mayumi Nagisa

Etsushi Takahashi

Etsushi Takahashi

However, Yuki is extremelyreticent about her private life and something of a control freak, so she makesHibino promise that they won’t use any photos she dislikes. Having a highopinion of himself, he’s a little insulted by this, but reluctantly agrees, allthe time wondering why he’s been given such an assignment. He has ambitions asa serious photojournalist and has covered the conflict in Biafra, a place heintends to head back to as soon as he gets a chance. He gradually learns that Yukiis in the process of getting over a relationship with a man (whom we neversee), and there also seems to be something between her and magazine boss Harada(Jiro Tamiya), but he can’t help being drawn to her despite himself…

In 1969, the star ofthis film, Ruriko Asaoka, had a hit single with a song entitled ‘Ai no kaseki’,which you can listen to on YouTube here. Needless to say, this film made tocapitalise on that success has precious little connection with the song, otherthan the vague theme of yearning for a lost love. Although we don’t hear Asaokasing it during the course of the movie, an instrumental version plays out overthe opening credits and the melody recurs at various point throughout.

Director YoshihikoOkamoto (1925-2004), who co-wrote the film with Koichi Suzuki, had a backgroundin socially-conscious TV dramas such as Shinobu Hashimoto’s I Want to Be a Shellfish (1958), forwhich he had won an award (and which Hashimoto himself would remake for thecinema the following year). Ai no kasekiis the second of just three feature films by Okamoto, following Tsugaru zessho (‘Tsugaru song’, 1970)and preceding Seishun no umi (‘TheSea of Youth’, 1974). In terms of direction, it’s pretty good, and verywell-shot mostly (if not entirely) on location by cinematographer Yuji Okumura,who was director Yoshishige Yoshida’s regular cameraman during this period.

The problem with Ai no kaseki is the story, which – asone might expect from a film inspired by a pop ballad – is simply too thin andnot terribly interesting; it literally goes nowhere. There’s a lot ofthen-topical talk about Biafra, an eastern region of Nigeria which had secededfrom the country in 1967, sparking a civil war which lasted two and a halfyears, after which it was reintegrated into Nigeria. Around one million peoplewere said to have died as a result of the conflict, many from starvation. PerhapsOkamoto sincerely wanted to draw people’s attention to this, but, if so, havinghis privileged characters express their concerns about it in this type of film maynot have been the best way, and, unfortunately, the issue of whether Hibinoreally cares about Biafra or just sees it as a means to win awards is neverreally explored.

In terms of the cast,Jiro Tamiya is wasted in a role which gives him little to do and EtsushiTakahashi was a limited actor better suited to action roles. Ruriko Asaoka is fineas usual, but it’s not enough to save this one – not unless seeing her in anendless parade of trendy outfits is enough for you, that is.

The film was producedby Yujiro Ishihara’s company – who had Asaoka under contract at the time – anddistributed by Nikkatsu.

Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Thanks to A.K.

July 17, 2025

Daikon to ninjin / 大根と人参 / (‘Radishes and Carrots’, 1965)

Chishu Ryu

Chishu Ryu Yamaki (Chishu Ryu) isa typical middle-aged salaryman who has worked his way up into a comfortable seniormanagement position. He’s been married to Nobuyo (Nobuko Otowa) for 28 years,has four adult daughters and is a creature of habit who rarely deviates fromhis daily routine. As his younger brother and subordinate co-worker Kosuki(Hiroyuki Nagato) says, he’s ‘as ordinary as radishes and carrots’.

Hiroyuki Nagato and Nobuko Otowa

Hiroyuki Nagato and Nobuko Otowa

However,problems begin to pile up – a friend (Kinzo Shin) has cancer but hasn’t beentold, Kosuki has embezzled money from the company and is expecting Yamaki tobail him out, and he’s been getting into increasingly aggressive arguments withhis best friend, Suzuka (Isao Yamagata), to whose son his youngest daughter(Mariko Kaga) is sngaged.

One day, his family are shocked when he fails toreturn from work. Unbeknownst to them, he’s gone off to Osaka, where he becomesinvolved with a cheerful call girl (Miyuki Kuwano) and her eccentric pimp (DaisukeKato), who also has a Chinese medicine business he wants Yamaki to come in onwith him…

This Shochiku comedyfeatures an all-star cast which also includes Ineko Arima, Mariko Okada andYoko Tsukasa as Yamaki’s other three daughters as well as Ryo Ikebe and ShimaIwashita, although some of these big names (especially Ikebe) are given preciouslittle to do. At the beginning of the film, we’re presented with statisticsinforming us that over 80, 000 people go missing per year in Japan – aphenomenon which seems an odd topic for comedy. The film originated from an idea by Yasujiro Ozu, no less, who took his inspiration from a short story by RyunosukeAkutagawa entitled ‘Yamagamo’, which centres around a quarrel between two oldfriends, and worked up a treatment with his regular collaborator Kogo Nodawhich remained unfinished. It seems likely that the theme of a man who goesmissing was added later by credited screenwriters Yoshio Shirasaka and MinoruShibuya, the latter of whom directed the film (his penultimate feature).

Nobuko Otowa and Mariko Okada

Nobuko Otowa and Mariko Okada

Shima Iwashita

Shima Iwashita

Although this isactually the first film I’ve seen by Shibuya, he was known for somewhat cynicalcomedies and it’s clear that Daikon toninjin is far closer to his usualstyle than it is to Ozu’s. In fact, one of the pleasures of the film is seeing itsunlikely lead, Chishu Ryu, send up all those ‘perfect father’ roles he playedfor Ozu over the years. There’s also some surprisingly frank sexual dialoguethat would not have been found in an Ozu picture. While Yamaki’s disappearance isnot really given sufficient motivation, and the film does seem a rather messy,cobbled-together affair, it remains quite entertaining and likeable, andcertainly worth a watch for anyone with an affection for the Japanese actors ofthe era.

Thanks to A.K.

July 12, 2025

Confession / 色ざんげ / Iro zange (‘Confession of a Love Affair’, 1956)

Yuasa (Masayuki Mori)is a middle-aged painter in the process of divorcing his wife (Hisano Yamaoka)and in love with the much younger Tsuyuko (Mie Kitahara), who reciprocates hisfeelings. However, Tsuyuko’s father (Ichiro Sugai) is dead set against thematch and packs her off to America in the hope that she’ll forget about Yuasa.While she’s gone, Yuasa decides he’d better accept the situation and gets marriedinstead to another much younger woman, Tomoko (Keiko Amaji), but she just likesthe idea of being married to a famous painter and continues to see her formerstudent boyfriend, Kunihiko (Joe Shishido) on the sly. Then Tsuyuko returns fromAmerica…

This Nikkatsuproduction was based on a novel originally published as a serial between 1933and 1935 by Chiyo Uno (female, 1897-1996). The character of Yuasa was based onthe painter Seiji Togo (1897-1978), with whom Uno had an affair that lastedfrom 1930-34. The story must have seemed old-fashioned even in 1956, and it’sdoubtful that the film was very successful commercially as Uno’s work was notadapted for the screen again until 1984. Nikkatsu is also a studio not knownfor its tragic love stories and would soon focus its attention on producinggangster movies aimed at the youth market.

The fact that thecentral character of Yuasa never really convinces or comes to life leaves thisfilm dead in the water. The other characters are constantly making a fuss aboutwhat an amazing artist he is, but we see no evidence of this except a notparticularly impressive portrait of Tsuyuko dressed like Little Bo Peep. As wenever see the beginning of their relationship, it’s impossible to understandhow these two were drawn to each other in the first place. Worse still, itseems that we’re expected to sympathise with how hard life must be for Yuasa asa wealthy middle-aged younger-woman magnet who lives a life of idleness. WhenTsuyuko’s father understandably prevents him from getting what he wants, Yuasamopes his way through the remainder of the film wallowing in self-pity,Masayuki Mori rarely deviating from his patented Staring Into The Voidexpression.

The cast also includesKinuyo Tanaka (wasted here as a friend of Yuasa’s) and a thin-faced Joe Shishidobefore the cheek job, but it’s the great Hisano Yamaoka who steals it here asthe ex-wife who’s probably supposed to be a shrew, but for whom I felt quitesympathetic, though not quite as much as I did for Yuasa’s second wife Tomokowhen she complains about being, ‘Bored, bored, bored!’

This is the first filmI’ve seen by director Yutaka Abe (1895-1977), who had lived in America fromaround 1912-24 and worked in Hollywood, first as an extra and later as afeatured actor. This experience led to him becoming a director after his returnto Japan, and he directed his first film there in 1925. I can’t say that I wasmuch impressed by his work in Confession,in which he lets the same scene between Mori and Shishido play out twice (firston a beach, then again immediately afterwards in a hotel room) and uses wavescrashing against rocks as a visual metaphor for passion – something I’m prettysure was a hoary old cliché even then.

Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Thanks to A.K.