M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 9

October 11, 2024

She Came for Love / 女が愛して憎むとき / Onna ga aishite nikumu toki (‘When a Woman Loves and Hates’, 1963)

Obscure Japanese Film #138

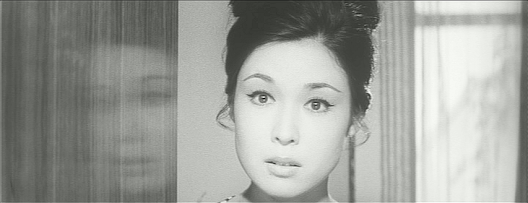

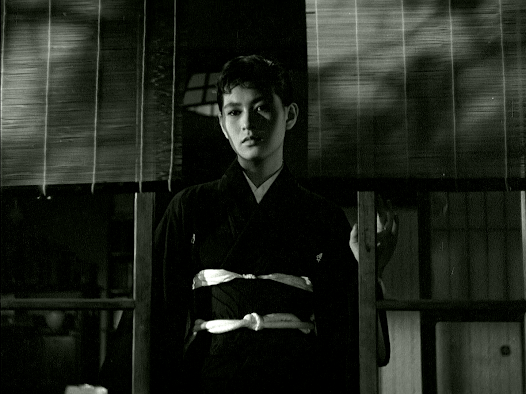

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoToshiko (Ayako Wakao)is the madam of a bar in Osaka who tries to keep her private life private andclaims not to have a lover. However, she is in fact having a secret affair withOzeki (Jiro Tamiya), a concert promoter who specialises in booking Americanartists and dreams of bringing Elvis to Japan. Ozeki is married and reluctantto leave his wife (Tazuko Niki), as she can speak English, which is veryhelpful to his business. Toshiko is well aware of all this but is apparentlysatisfied with the arrangement.

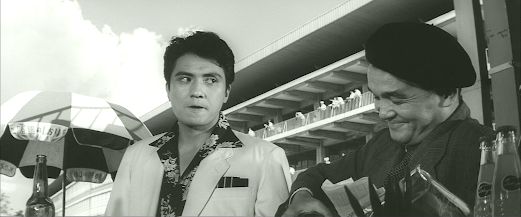

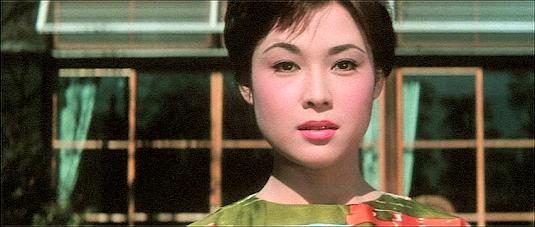

Jiro Tamiya and Ayako Wakao

Jiro Tamiya and Ayako WakaoAlthough Toshiko’s baris successful and she is a popular hostess, problems begin to arise. Herdespised ex-husband (Akihiko Katayama) reappears and keeps bugging her; one ofher employees, Nobuko (Kyoko Enami), is being a bit too flirtatious with thecustomers; Ozeki is making some risky deals and getting in over his head; andher former boss and mentor, Rie (Mitsuko Mori), is unhappy with her becauseToshiko’s cheap whisky is tempting customers away from Rie’s bar…

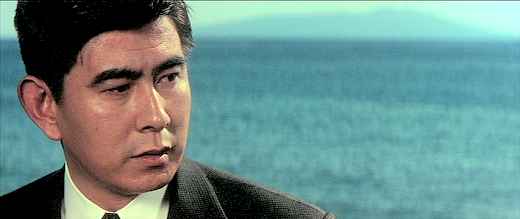

Kyoko Enami

Kyoko EnamiAt times watching this,I was reminded of Naruse’s When a WomanAscends the Stairs (1960), which is understandable as not only does thisDaiei production cover similar territory, but it turns out that, like Naruse’sfilm, it also has an original screenplay by Ryuzo Kikushima (a frequentcollaborator of Akira Kurosawa). The story is character-driven rather thanplot-driven – something which is a major strong point of the script for me, andgives Wakao an excellent role which she plays to perfection. Toshiko undergoesa rather bitter inner journey and is not the same person at the end of the filmthat we met at the beginning. She Camefor Love may well be a case of the script and cast being more importantthan the director, though the little-known Sokichi Tomimoto handles all aspectswell. In any case, it’s a fine film which deserves to be better-known, and itshould be a must for all fans of Ayako Wakao.

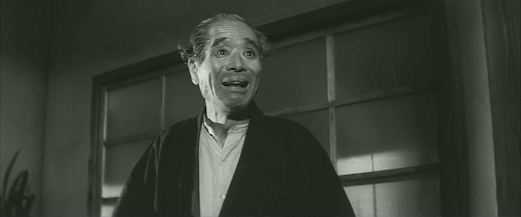

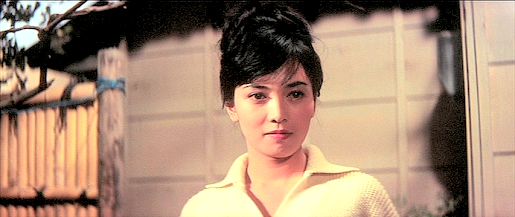

Mitsuko Mori

Mitsuko MoriAlthough quite famous inher home country, Mitsuko Mori (who plays the important role of Rie soconvincingly) is unlikely to be familiar to many non-Japanese viewers as she hada patchy film career, first appearing in 58 films between 1935 and 1941, mostof which were undistinguished B-pictures. After a long hiatus from the bigscreen, she made two films in 1957, and then worked in films fairly steadily –mainly in supporting roles – from 1961 until the early 1970s. However, during most of her periods of absence from the cinema she wasbusy with radio,television and stage work. Her signature role was as author Fumiko Hayashi in thestage version of Hayashi’s autobiographical work, A Wanderer’s Notebook; she performed this over 2,000 times from1961, although when Mikio Naruse filmed it the following year, it was Hideko Takaminewho won the part. No surprise, then, that Mori never went on to make a film with Takamine,although Naruse subsequently employed her for a part in his final film, Scattered Clouds (1967).

Thanks to A.K., and to Coral Sundy for the subtitles, which can be found here.

October 9, 2024

The Invisible Wall / 眼の壁 / Me no kabe (‘Wall of Eyes’, 1958)

Obscure Japanese Film #137

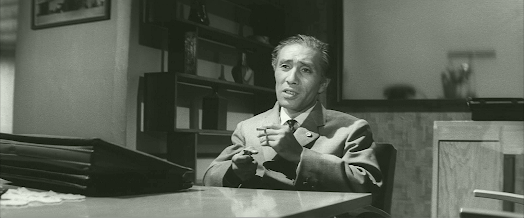

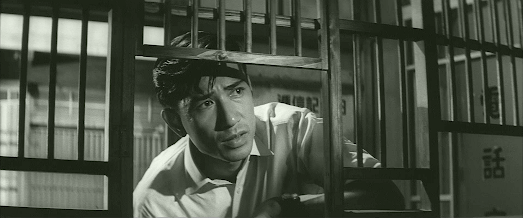

Keiji Sada

Keiji SadaThis Shochikuproduction stars Keiji Sada as Hagisaki, the deputy head of an accountsdepartment whose boss, Sekino (Masao Oda), commits suicide. Hagisaki receives aletter from the dead man explaining that he felt it was the only way to takeresponsibility for losing 30 million yen of the company’s money as a result ofa scam.

Despite being warned bythe company’s lawyer, Segawa (Ko Nishimura), not to interfere, Hagisaki takesit upon himself to investigate and joins forces with his friend Tamura, ajournalist (Shinji Takano). Their clues lead them first to the Red Moon bar onthe Ginza, and eventually to a mountain village in Nagano.

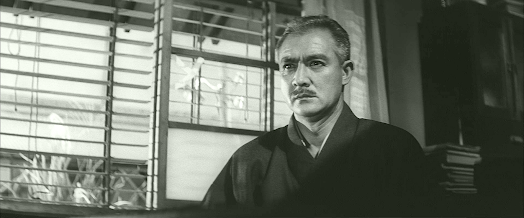

Fumio Watanabe and Jun Tatara

Fumio Watanabe and Jun Tatara

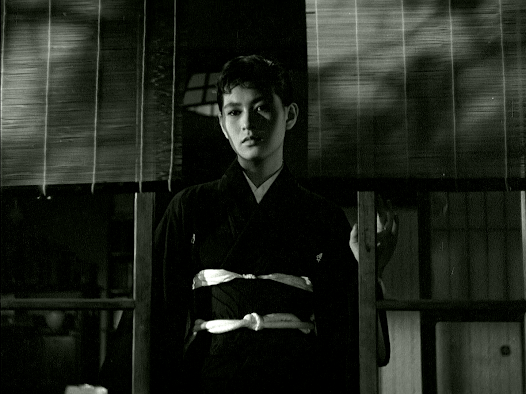

Yachiyo Otori

Yachiyo Otori

Among the other peopleinvolved in the mystery are bartender Yamamoto (Fumio Watanabe), a privatedetective (Jun Tatara), a moneylender’s secretary named Etsuko (Yachiyo Otori)and right-wing politician Funasaka (Jun Usami), but it proves to be a crustyold villager (Bokuzen Hidari) who provides the key to the mystery before eventsreach a gruesome climax involving an acid bath…

Based on a novel of thesame name by popular mystery writer Seicho Matsumoto, this story is typical ofthe author’s work, but not one of the best adaptations of it. Masayoshi Ikeda’ssuspenseful music score helps, but the story is allowed to become a little toocomplicated for its own good and fails to maintain the interest as a result.

Italso doesn’t help that the hero, Hagisaki, is such a blank slate of a character– Keiji Sada was a good actor, but he’s given very little to work with here,which is at least partly his own fault as he was a big enough star to have madechanges if he had cared to. It’s competently but rather indifferently directedby Hideo Oba, best known for his What IsYour Name? trilogy (1953-54), which also starred Keiji Sada, but theproceedings are occasionally enlivened by some of the excellent characteractors who pop up along the way.

Leading lady YachiyoOtori had been a stage star for the Takarazuka theatre company; this was herfirst film under contract to Shochiku. She makes little impact here, althoughit’s not much of a role, to be fair. Her film career never really took off andshe had more success on stage and television. At the time of writing, she’sstill alive at the age of 91.

October 3, 2024

Bara no ki ni bara no hana saku / 薔薇の木にバラの花咲く / (‘Roses Bloom on the Rose Bush’, 1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #136

Ayako Wakao

Ayako Wakao Rieko Sumi and Ayako Wakao

Rieko Sumi and Ayako WakaoReiko (Ayako Wakao) isa senior university student majoring in English who gets a part-time jobtutoring junior student Mariko (Noriko Kubota). This is valuable income asReiko lost both parents in the war and the only family she has left is herelder sister, Ginko (Rieko Sumi), who has become involved with the no-good Nose(Manabu Morita) and ended up working in the red light district.

One day at Mariko’shouse, Reiko meets a young architect, Fuyuhiko (Jiro Tamiya), who isimmediately attracted to her. Coming from a wealthy family and used to havinghis own way, he pursues her relentlessly until his persistence pays off. Reikobegins a relationship with him which soon leads to talk of marriage. However,there is also the matter of Reiko’s sister, whose status would make the matchunacceptable to Fuyuhiko’s family, as well as Reiko’s friendship with fellowstudent Narumi (Keizo Kawasaki), who loves her but has so far kept his feelingsto himself…

This Daiei productionwas based on a novel of the same name by Yoshiko Shibaki, whose work had alsoformed the basis of Mizoguchi’s Akasenchitai and Yuzo Kawashima’s lesser-known but excellent Suzaki Paradise (both 1956), both of which were stories of the redlight district. Like those films, this is also concerned with people who havefound themselves marginalised by society partly due to economics, but here thered light district is a minor element and the main focus is on social status,or the class divide, a theme seldom dealt with in Japanese films as explicitlyas it is here.

The director wasHiroshi Edagawa (1916-2010), a filmmaker credited with just two feature filmson IMDb, but who actually directed 31 features between 1950 and 1965 beforefinishing his career in TV, which shows just how much info is still missing onIMDb. Not having seen any of his other films, I can’t say how this onecompares, but his work here is more than competent and he succeeds indelivering a satisfying and affecting Naruse-like relationship drama with goodperformances all round.

The characters here actuallyresemble real people – Jiro Tamiya’s, for instance, could easily have been aone-dimensional spoilt rich kid type, but is portrayed as having both positiveand negative traits, while Ayako Wakao’s heroine is also shown to have her ownflaws (embarrassed by her sister, she later comes to realise how lucky she isto have her). This unusual attention to character is probably why I foundmyself so drawn into the story and caring about what happened to the fictionalpeople on screen. Given the obscurity of both film and director, I didn’t expect much from this, but I have to say I was very pleasantlysurprised and warmly recommend it.

Thanks to A.K.

September 30, 2024

Modae / 悶え (‘Agony’, aka ‘The Night of the Honeymoon’, 1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #135

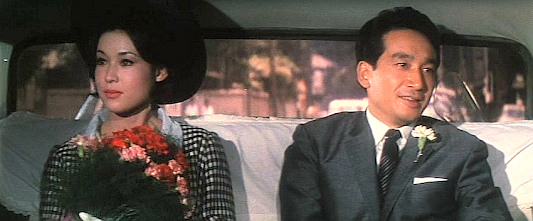

Ayako Wakao and Masaya Takahashi

Ayako Wakao and Masaya TakahashiNewlyweds Chieko (Ayako Wakao) and Ueda(Masaya Takahashi) head off to a hot spring inn in Hakone for their honeymoon,but the virginal Chieko is surprised when her husband avoids touching her ontheir wedding night and even more confused when this behaviour continues thefollowing day. It transpires that Ueda is impotent as a result of a caraccident, but his doctor has advised him that his condition may not bepermanent and marriage may help.

Kyoko Enami and Ayako Wakao

Kyoko Enami and Ayako WakaoMeanwhile, Chieko bumpsinto an old high school friend, the sexually-liberated Michiko (Kyoko Enami),who happens to be staying at the same hotel (unlikely coincidence #1) with agroup of hedonistic friends, one of whom, Ishikawa (Yusuke Kawazu), immediatelystarts flirting with her. Later, Chieko is with her husband when she again runsinto Ishikawa, who it turns out works in the same office as Ueda as anunderling (unlikely coincidence #2).

Yusuke Kawazu

Yusuke KawazuNext, Ishikawa’s aunt,Mrs Shiraki (Murasaki Fujima), turns up looking for him. She has her own beautysalon and appears to regard Ishikawa as more than a mere nephew, but hecontinues to be more interested in Chieko despite the fact that she’s marriedto his boss. However, Chieko continues trying to help her husband overcome hisproblem, but every he tries to get it on with her, they are subjected todramatic music, red lighting and images of swirling paint…

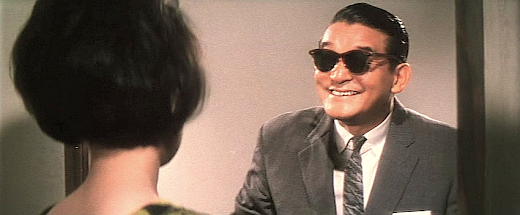

Based on a 1960 novel by Taiko Hirabayashi entitled Ao to kanashimi no toki (‘Time of Love and Sadness’), this slightlybatty psycho-sexual drama from Daiei proves to be quite enjoyable, if only forthe fact that it’s not formulaic or predictable, and you never quite know whereit’s going to go. The performances are also good, with Murasaki Fujima makingthe most out of her minor role, as does Jun Tatara as a wheedling doctor indark glasses claiming to have the couple’s best interests at heart, but seemingto have another agenda.

Murasaki Fujima

Murasaki Fujima Jun Tatara

Jun TataraHowever, I felt that Masaya Takahashi lacked a bit of presenceas Ueda and the film might have been more interesting with the more masculineJiro Tamiya in the role. Of course, Ayako Wakao is excellent, although her roleis a bit too typical of the parts shewas being given at the time and must have presented little challenge. DirectorUmetsugu Inoue was averaging 5-6 films a year at this point, and there’snothing to suggest he took any special pains over this one, but it’s at leastbetter than the recently-reviewed Bury MeDeep.

Thanks to A.K., and toCoral Sundy for the subtitles, which can be found here.

September 25, 2024

A Hole of My Own Making / 自分の穴の中で / Jibun no ana no nakade (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #134

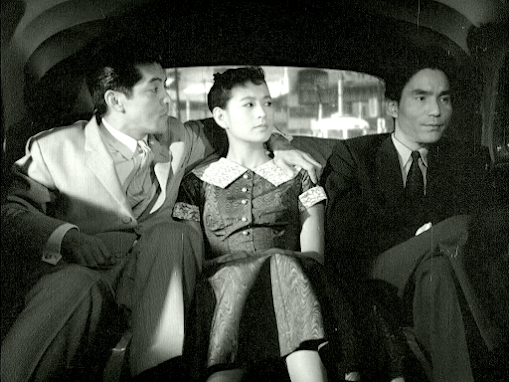

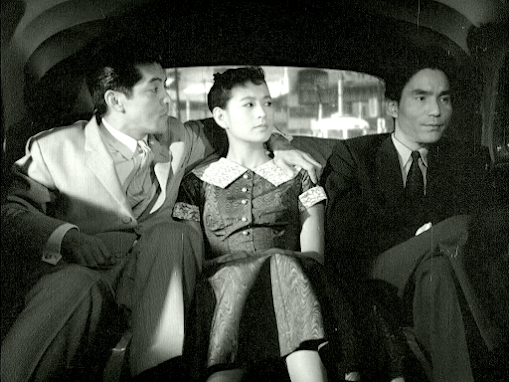

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi Uno

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi UnoTamiko (Mie Kitahara)is a young woman living at home with her stepmother, Nobuko (Yumeji Tsukioka),and her bedridden brother, Junjiro (Nobuo Kaneko). Tamiko’s parents are bothdeceased and she’s approaching the usual age for marriage, so candidates arebeing discussed. Her father had wanted her to marry Komatsu (Jukichi Uno), aneasygoing nice guy who works in a munitions factory, but she’s not attracted tohim. Tamiko prefers the more aggressive and ambitious Ihara (Rentaro Mikuni), amedical doctor who spends most of his time experimenting on animals when he’snot womanising. However, she mistakenly believes that Nobuko wants him forherself, and this becomes a major source of friction between the two women.Meanwhile, Junjiro – who has never got over the fact that his wife left him –is becoming increasingly obsessed with investing in stocks and shares…

Yumeji Tsukioka

Yumeji TsukiokaThis Nikkatsuproduction was based on an untranslated 1955 novel of the same name by the left-wing writer TatsuzoIshikawa (1905-85), whose work was also to provide the basis for several SatsuoYamamoto films, including The Human Wall(1959). Ishikawa had actually been imprisoned by the Japanese authorities for afew months in 1938 as a result of his novel SoldiersAlive, which criticised the Japanese presence in China; he subsequentlyavoided such topics until after the war. AHole of My Own Making was adapted for the screen by Yasutaro Yagi, who hadwritten a number of scripts for this film’s director, Tomu Uchida, back in the1930s, before Uchida disappeared into Manchuria for a decade or so. The factthat Uchida chose to work with these two writers and that the resulting filmshows so little regard for commercial considerations (with the possible exceptionof its casting) leaves little doubt that it was a personal passion project and byno means a routine studio assignment.

Nobuo Kaneko

Nobuo KanekoLike Uchida’s previousfilm, Twilight Saloon, it also seemsto be something of an allegory for post-war Japan, perhaps most obviously inthe character of Junjiro, a disillusioned and broken man pursuing financialwealth for its own sake from his sickbed. However, despite the rich symbolismthat can be found throughout, I’ve seldom seen a film which leaves it so much upto the audience to decide how to feel about the characters, especially in thecase of Tamiko and Nobuko. Who exactly are we supposed to be rooting for here? It’sso unclear that it’s almost disorienting in comparison to the majority ofmovies, and it’s difficult even to be certain about which character is referredto in the title – a hole of whose ownmaking? Initially, I thought it must have been referring to Komatsu, who isintroduced at the beginning of the film sleeping in a drainage tunnel (?), but by the end Ithought it made more sense referring to Tamiko… Anyway, I personally enjoyed the film’s ambiguity, though I can imagine that some might feel exasperated and lose patience.

Mie Kitahara

Mie KitaharaEven moreunconventional is the harpsichord score by Yasushi Akutagawa (son of Rashomon writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa!),which at times sounds like it's being played by a demented chimp. Weirdly, I kind of liked this too, andyou certainly can’t accuse anyone of going for the obvious here. Talking ofmusic, Nobuko and Ihara attend a kotoconcert around half an hour in, and the blind musician we see performing is quitesomething. He is Michio Miyagi (1894-1956), one of the all-time greats oftraditional Japanese music.*

Michio Miyagi

Michio MiyagiThe actors are all wellcast and the performances solid all round. Mikuni dissects a live frog at onepoint, and doesn’t appear to have faked it – unsurprising as he was known fortaking realism to extremes. The point was presumably to underline the character’slack of feeling, but I have to say that I thought it was unnecessary.

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-star

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-starTo return to the film’suse of metaphors, a new sports centre is being built outside Tamiko’s familyhome, and construction noises are audible in every daytime scene set in thatlocation – clearly a deliberate if unusual choice, and one that I think was intendedto suggest that the old way of life is coming to an end. As in therecently-reviewed film A Rainbow at EveryTurn (1956), military jets fly over in several scenes, including right at the end,implying an uncertain future not just for Tamiko and what’s left of her family,but for the Japanese people as a whole. But Uchida never represents hischaracters in this film as simple victims of change – many of them areunlikeable and are pursuing selfish goals, and in various ways they bring theirmisfortunes on themselves. Perhaps the title refers to more than one of thecharacters after all, and of course it could be taken to refer to the Japanese nation as a whole, so A Hole of Our Own Making might have been a better fit.

*Despite his blindness, Miyagi also composedthe score for a 1935 version of PrincessKaguya photographed by special effects whiz Eiji Tsuburaya. A shortenedversion (33 minutes instead of the original 75) was rediscovered in the UK in 2015.An excerpt can be viewed on YouTube here.

Thanks to A.K.

For more on A Hole of My Own Making, click here.

A Hole of My Own Making / /自分の穴の中で / Jibun no ana no nakade (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #134

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi Uno

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi UnoTamiko (Mie Kitahara)is a young woman living at home with her stepmother, Nobuko (Yumeji Tsukioka),and her bedridden brother, Junjiro (Nobuo Kaneko). Tamiko’s parents are bothdeceased and she’s approaching the usual age for marriage, so candidates arebeing discussed. Her father had wanted her to marry Komatsu (Jukichi Uno), aneasygoing nice guy who works in a munitions factory, but she’s not attracted tohim. Tamiko prefers the more aggressive and ambitious Ihara (Rentaro Mikuni), amedical doctor who spends most of his time experimenting on animals when he’snot womanising. However, she mistakenly believes that Nobuko wants him forherself, and this becomes a major source of friction between the two women.Meanwhile, Junjiro – who has never got over the fact that his wife left him –is becoming increasingly obsessed with investing in stocks and shares…

This Nikkatsuproduction was based on a 1955 novel of the same name by the left-wing writer TatsuzoIshikawa (1905-85), whose work was also to provide the basis for several SatsuoYamamoto films, including The Human Wall(1959). Ishikawa had actually been imprisoned by the Japanese authorities for afew months in 1938 as a result of his novel SoldiersAlive, which criticised the Japanese presence in China; he subsequentlyavoided such topics until after the war. AHole of My Own Making was adapted for the screen by Yasutaro Yagi, who hadwritten a number of scripts for this film’s director, Tomu Uchida, back in the1930s, before Uchida disappeared into Manchuria for a decade or so. The factthat Uchida chose to work with these two writers and that the resulting filmshows so little regard for commercial considerations (with the possible exceptionof its casting) leaves little doubt that it was a personal passion project and byno means a routine studio assignment.

Like Uchida’s previousfilm, Twilight Saloon, it also seemsto be something of an allegory for post-war Japan, perhaps most obviously inthe character of Junjiro, a disillusioned and broken man pursuing financialwealth for its own sake from his sickbed. However, despite the rich symbolismthat can be found throughout, I’ve seldom seen a film which leaves it so much upto the audience to decide how to feel about the characters, especially in thecase of Tamiko and Nobuko. Who exactly are we supposed to be rooting for here? It’sso unclear that it’s almost disorienting in comparison to the majority ofmovies, and it’s difficult even to be certain about which character is referredto in the title – a hole of whose ownmaking? Initially, I thought it must have been referring to Komatsu, who isintroduced at the beginning of the film sleeping in a drainage tunnel, but by the end Ithought it probably referred to Tamiko… Anyway, I personally enjoy the film’s ambiguity, though I can imagine that some might feel exasperated and lose patience.

Even moreunconventional is the musical score by Yasushi Akutagawa (son of Rashomon writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa!),which at times sounds like a demented chimp let loose on an electric harpsichord. Weirdly, I kind of liked this too, andyou certainly can’t accuse anyone of going for the obvious here. Talking ofmusic, Nobuko and Ihara attend a kotoconcert around half an hour in, and the blind musician we see performing is quitesomething. He is Michio Miyagi (1894-1956), one of the all-time greats oftraditional Japanese music.*

The actors are all wellcast and the performances solid all round. Mikuni dissects a live frog at onepoint, and doesn’t appear to have faked it – unsurprising as he was known fortaking realism to extremes. The point was presumably to underline the character’slack of feeling, but I have to say that I thought it was unnecessary.

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-star

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-star

To return to the film’suse of metaphors, a new sports centre is being built outside Tamiko’s familyhome, and construction noises are audible in every daytime scene set in thatlocation – clearly a deliberate if unusual choice, and one that I think was intendedto suggest that the old way of life is coming to an end. As in therecently-reviewed film A Rainbow at EveryTurn (1956), military jets fly over in several scenes, including right at the end,implying an uncertain future not just for Tamiko and what’s left of her family,but for the Japanese people as a whole. But Uchida never represents hischaracters in this film as simple victims of change – many of them areunlikeable and are pursuing selfish goals, and in various ways they bring theirmisfortunes on themselves. Perhaps the title refers to more than one of thecharacters after all.

*Despite his blindness, Miyagi also composedthe score for a 1935 version of PrincessKaguya photographed by special effects whiz Eiji Tsuburaya. A shortenedversion (33 minutes instead of the original 75) was rediscovered in the UK in 2015.An excerpt can be viewed on YouTube here.

Thanks to A.K.

For more on A Hole of My Own Making, click here.

September 22, 2024

Bury Me Deep / わたしを深く埋めて / Watashi o fukaku umete (1963)

Obscure Japanese Film #133

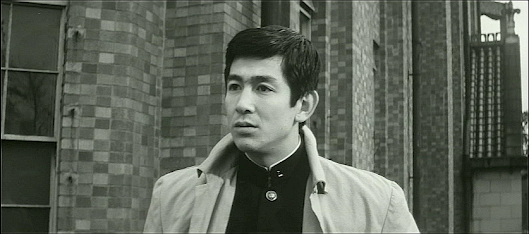

Jiro Tamiya

Jiro TamiyaNakabe (Jiro Tamiya) isa lawyer returning to Tokyo after a long holiday in Kyushu. In his absence, helent his apartment to his best friend, Akutagawa (Keizo Kawasaki), whosemarriage to Chizu (Ayako Wakao) is falling apart. Arriving back at hisapartment, Nakabe is astonished to find a random drunk woman on his sofa whoimmediately tries to seduce him. However, she’s so drunk that she falls asleepin the process, enabling Nakabe to get rid of her in a taxi (not sure that ataxi driver would accept an unconscious passenger with no address, but plausibilityis not high on the agenda here). When the woman dies in the back of the cab,the cops come looking for Nakabe, who then has to track down Akutagawa to provehis innocence and ends up becoming involved with Chizu…

This Daiei mystery wasbased on a 1947 novel of the same name by American writer Harold Q. Masur, thefirst in his long series of books featuring a Perry Mason-like lawyer, ScottJordan. Surprisingly, this appears to have been the only film to have resultedfrom this series, although perhaps it’s not so strange considering that Americanpulp fiction became very popular in Japan during the post-war occupation, and agreat deal of it was published in translation there.

Unfortunately, Bury Me Deep has a convoluted plot thatfails to maintain the interest, and there’s a lot of overacting from thesupporting cast, although it’s always good to see Kyoko Enami, even in a daftrole like the one she gets here. Tamiya is in virtually every scene and is fine,while Ayako Wakao has significantly less screen time, but it’s a testament to the sincerity of her acting that she almost makes you believe the silly dialogue she hasto deliver in her big scene at the end.

Director Umetsugu Inouehad just made a great film called TheThird Shadow Warrior immediately before this, so this is quite a let-downin comparison and it’s tempting to say that this film reallyshould be buried deep…

Thanks to A.K. and toCoral Sundy for the English subtitles which can be found here.

September 19, 2024

A Rainbow at Every Turn / 虹いくたび / Niji ikutabi / (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #132

Machiko Kyo and Ayako Wakao

Machiko Kyo and Ayako WakaoBefore I begin, I should point out that, although I don’t usuallywrite a synopsis that includes the ending, on this occasion I will be discussingthe ending and its differences from the book…

Momoko (Machiko Kyo) and Asako (Ayako Wakao) are half sistersstill living at home with their widowed father, Mizuhara (Ken Uehara). Themother of Momoko, the older of the two, committed suicide, while Asako’s motherdied of illness. However, Mizuhara actually has a third daughter, Wakako(Yasuko Kawakami), born out of wedlock, who lives in Kyoto and whose mother, Kikue(Haruyo Ichikawa) is still alive. Asako – warm, sensitive and compassionate andwith a desire to help others – is keen to meet Wakako, but the rather cold,bitter and cynical Momoko advises her not to meddle.

Momoko’s family believe that she is suffering from a broken heart dueto the suicide of her mother and also because her boyfriend, Keita (KeizoKawasaki), was killed at Okinawa during the war, but there is more to it thanthat…

In a flashback sequence, we learn that before Keita left for aprobable death, he had persuaded Momoko to let him make a tea bowl from a mouldof her breast, which he could take with him to the front line and enjoy hisfinal drink from. During the same evening, he persuaded her to sleep with him,after which he unexpectedly insulted her and left, leaving her shocked andconfused.

Now, Momoko has been attempting to fill the void by having anaffair with Takemiya (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), a student several years her junior, buthe is a highly emotional young man who can’t take it when he realises thatMomoko is not serious about their relationship. When he commits suicide, Momokonot only has yet another tragic death to process, but finds herself pregnant withhis child.

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Machiko Kyo

Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Machiko Kyo

Meanwhile, Keita’s brother, Natsuji (also played by KeizoKawasaki), wants to meet his dead brother’s girlfriend, but Momoko hates him onsight due to his strong resemblance to his brother… However, Natsuji ends upbecoming friendly with Asako instead, and relations between the families ofMomoko and Keita continue. Keita’s father, Aoki (Bontaro Miake), apologises toMomoko for the conduct of his son, explaining that Keita had insulted her onlybecause he loved her so much and didn’t want her to grieve if he waskilled. He even persuades her to keepTakemiya’s child, and Momoko’s heart finally thaws…

Koji Shima’s film starts out very faithful to Yasunari Kawabata’s1951 novel of the same name, which has recently appeared in English for the firsttime as The Rainbow. However, much ofKawabata’s novel consists of conversations the characters have about flowers,art and architecture, etc, which have little direct bearing on the plot, soit’s understandable that the film dispenses with most of these. The film alsoprovides a clear explanation of Keita’s motivation for insulting Momoko,whereas in the book this can be perhaps be inferred but is never spelt out. Butthe most significant difference is in the ending. In the novel, Momoko issubtly manipulated by her father and Aoki into having her baby aborted andhates herself for having gone along with it. The book ends with Momoko finallybeing formally introduced to her other half sister Wakako, but the meeting isstiff and awkward. It’s not hard to see why Daiei wanted to change this ending– even though sad endings are far more common in the Japanese cinema than inHollywood movies, such an unsentimental finish was unlikely to have beenwell-received.

In the film, the baby represents the possibility of futurehappiness for Momoko, whose meeting with Wakako – with the whole family present– is far warmer and more satisfactory. Momoko thinks she sees a rainbow, andthen everyone rushes to the window to see it, but there’s nothing there andthey all laugh cheerfully. However, the very last shot is of a military jetflying past the window. This is rather puzzling, and I’m not sure I would haveunderstood why Shima did this if I hadn’t read the book (and even now I’mspeculating to some extent). It should also be noted that we hear a militaryjet fly over off-screen around 8 minutes into the film. There are no jets inthe book, but there is some talk about the A-bomb and the fact that thecharacters are now living in the nuclear age. For this reason, I believe thatthe final shot was Shima’s attempt to temper the apparently optimistic endingwith a little uncertainty so as not to entirely betray Kawabata’s intentions. Unfortunately,it doesn’t really work in my view and just seems a bit random and baffling.

Having recently reviewed Shima’s The Beloved Image (1960), I can see some similarities between thetwo films – both star Machiko Kyo, both are adapted from serious works ofliterature, both make good use of weather, and both feature a number of shotswhich are clearly symbolic; in A Rainbowat Every Turn, Kyo’s face is deliberately obscured on a couple of occasionsby a sliding shoji, characters are separated at certain moments by a conveniently-placedpost or similar, and at one point a close-up of Kyo’s face through a venetianblind seems to be equating her situation to the caged bird featured in the sameshot. However, the devastating ending of TheBeloved Image is clearly not compromised at all, and I believe that it wasin that later film that Shima was able to achieve exactly what he wanted.

After seeing these two films, it’s also clear that, although Shimawas one man, he was in effect two directors – the journeyman who made notparticularly intelligent commercial fare like The Phantom Horse and Warningfrom Space, and the artist who had loftier aspirations and was at leastsometimes able to realise these very well, as he does partially in this filmand fully in The Beloved Image. Beforehe became a director in 1939, Shima had been a star actor who had worked for distinguisheddirectors such as Kenji Mizoguchi and Tomu Uchida, so it’s safe to assume hehad learned a thing or two from them. In ARainbow at Every Turn, Shima uses few close-ups and keeps the camera mostly– but not entirely – static, while the only music is some classical style pianofeatured over the opening credits and finally being reintroduced during thefinal scene. This sober, unshowy style works in the film’s favour for the mostpart, while Machiko Kyo and Ayako Wakao are perfect casting as the two sisters –as a result of their fine performances, these two characters feel moresubstantial than they do in Kawabata’s novel. Unfortunately, the same cannot besaid of Hiroshi Kawaguchi, an actor better suited to comic roles who is miscasthere and unconvincing when required to break down emotionally. Overall, though,this is another film that provides strong evidence to suggest that Shima is adirector worthy of further investigation – once the films he made purely to paythe rent have been weeded out, anyway.

September 14, 2024

Ojo-san / お嬢さん (‘Young Miss’, 1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #131

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoKasumi (Ayako Wakao) is a young woman of marriageable age prone todaydreaming who believes that arranged marriages are better than love matches,while her best friend Chieko (Hitomi Nozoe) thinks the opposite. However,Kasumi finds herself strangely drawn to womaniser Sawai (Hiroshi Kawaguchi)despite the fact that her father (Masao Shimizu) thinks that one of hiscompany’s employees, Maki (Jiro Tamiya), is the most promising candidate forher hand…

Hitomi Nozoe

Hitomi NozoeThis Daiei comedy is clearly intended mainly as a vehicle forAyako Wakao, who not only receives a great many close-ups, but also gets towear a different outfit in each scene – in fact, she apparently designed all 22of these herself, and they were popular enough that one women’s clothes storein Tokyo even had an ‘Ojo-san’ section for a while.

Hiroshi Kawaguchi

Hiroshi KawaguchiSurprisingly, this project came about due to Wakao’s associationwith Yukio Mishima, who wrote the 1960 novel on which it was based. AlthoughMishima is famous as a writer of highbrow literature, he also wrote morelowbrow novels and stories to make a quick yen (most of which have not beentranslated into English). Ojo-san isclearly an example of the latter as it was originally published in serial formin a women’s magazine and the story is complete fluff. I have nothing againstlight comedies, but the film seemed neither particularly funny nor clever tome, and I found the whole thing rather pointless, although watchable enough.However, young women in Japan in the early 1960s may well have felt that itspoke to them in some way.

Jiro Tamiya

Jiro TamiyaWakao had first met Mishima when she appeared in a film version ofhis novel Nagasugita haru in 1957. Headmired her greatly and, when he starred in Afraidto Die (1960) for Daiei, he requested Wakao for his co-star. It was duringthe course of making that film that the two discussed Ojo-san – Wakao said she would like to play the part, and Mishimasold the rights to Daiei on the condition that the role went to her. He evenwrote two essays about her: ‘Ayako Wakao – The Woman on the Cover’ (1960) and ‘InPraise of Ayako Wakao’ (1962), although apparently they weren’t to see each otheragain after Mishima left Japan in November 1960 to spend a couple of monthstravelling with his wife. Later, Wakao appeared in film versions of Mishima’s Frolic of the Beasts (1964) and Spring Snow (2005) as well as in hisplay Rokumeikan on stage in 1988.

Here is a rough translation of some extracts from Mishima’s essay ‘InPraise of Ayako Wakao’:

Duringthe shooting [of Afraid to Die], Ifirst discovered (although it was a very late discovery) that "Ayako Wakaois no ordinary actress."… What I will never forget is her performance atthe climax of the film, when, after being thoroughly beaten by me, a tough, weakyakuza, she still refuses to abort the baby she is carrying, showing herwomanly determination… The instinct, naturalness and strength of herperformance, which delivers and enriches all the emotions required by the role,and also blends the three stages of stylistic change in between realisticallyto build up to a perfect climax, is absolutely magnificent, and as I watched, Ifelt that I had fallen 100% in love with her in my role.

Peoplejust can't resist that strawberry-like frozen taste [she has]. Because of this,she has always been popular but, at the same time, I think it was a majordetriment to her acting talent being recognised… An actor has to fight againsttheir looks. The more the public loves their looks, the more they have to fightagainst this. Ayako Wakao fought against this, and won splendidly.

The director of Ojo-san,Taro Yuge (1923-73), joined Daiei as an assistant director in 1947 but had towait until 1960 to become a director himself. In the meantime, he had workedunder Yasuzo Masumura and Kon Ichikawa among others, but his career was notterribly distinguished and ended when the studio went bankrupt in 1971. He wentmissing the following year and his body was discovered a year after that, hisdeath believed to have been a suicide. This sad event is probably emblematic ofhow difficult the collapse of Daiei must have been for a great many of itsemployees at the time. Of course, on a more positive note, the wonderful thing is that their films are not mouldering away in a vault, but have been well-preserved and are moreaccessible outside Japan now than they have ever been before.

Thanks to A.K.

September 10, 2024

Story of a Blind Woman /女めくら物語 / Onna mekura monogatari (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #130

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoThis Daiei productionstars Ayako Wakao as Tsuruko, an orphan who loses her sight at the age of 16and has little choice but to work as a masseur (the traditional occupation forthe blind in Japan). She goes to work for a small school / agency owned by Arifu*(played by Ganjiro Nakamura – always a red flag!), who is also blind, althoughsome of his other masseurs have partial eyesight. They all live together andare called out to inns when requested by customers.

Ken Utsui

Ken UtsuiOne night, a troubledbusinessman named Kigoshi (Ken Utsui) saves Tsuruko first from a fall and thenlater from some drunks. She falls in love with him, but he disappears.Meanwhile, needing another masseur as they are often short-handed, Arifu ispersuaded against his better judgment to hire Itoko (Mayumi Nagisa), who atfirst pretends to be blind in order to get the job. It soon becomes obviousthat she’s just out to grab what she can and doesn’t care what she has to do toget it – as long as there’s no actual work involved, that is. It’s not longbefore Itoko has pissed off her colleagues so much that some of them quit inprotest.

Mayumi Nagisa and Ganjiro Nakamura

Mayumi Nagisa and Ganjiro NakamuraWhen Tsuruko is againprevented from falling down some steps – this time by a young man passing inthe street – she is reminded of Kigoshi, and so feels well-disposed towards himwhen it turns out that he’s looking for a job as a masseur. This apparent goodSamaritan is Kenkichi (Junichiro Yamashita), who is blind in one eye. Tsurukopersuades Arifu to hire him, but unfortunately she lives to regret it…

Junichiro Yamashita

Junichiro YamashitaBased on a 1954 novelby Seiichi Funabashi (who, ironically, went blind himself shortly after thisfilm came out), Story of a Blind Womanfelt rather contrived to me, with one credibility-stretching coincidence aroundhalfway through and characters often seeming to act in the interests of theplot rather than their own best interests. However, Ayako Wakao makes for avery sympathetic tragic heroine and is quite convincing in her blindness. Shemostly achieves this by avoiding eye contact with her fellow actors and byusing her hands to feel her way along walls, etc (Ganjiro Nakamura uses thesimpler method of just keeping his firmly eyes closed throughout, but of coursethis film would not have worked had we been unable to see Wakao’s eyes).

Performances are decentall round, with Mayumi Nagisa especially effective as a person so smug in herselfishness that I’m sure even Mahatma Gandhi would cheerfully have throttledher with his bare hands given the chance. Nagisa also played the anti-Wakaocharacter in One Day at Summer’s End.

Mayumi Nagisa

Mayumi NagisaStoryof a Blind Woman benefits from a cliché-free music scoreby Seitaro Omori which uses traditional Japanese instruments in a modernist oravant-garde kind of way. The whole thing is also very nicely shot by directorKoji Shima and his DP Kimio Watanabe – I especially loved the shot of Wakaowalking towards the camera with which the film ends.

*I’m not sure if thisname is correct.

Thanks to A.K.