A Hole of My Own Making / 自分の穴の中で / Jibun no ana no nakade (1955)

Obscure Japanese Film #134

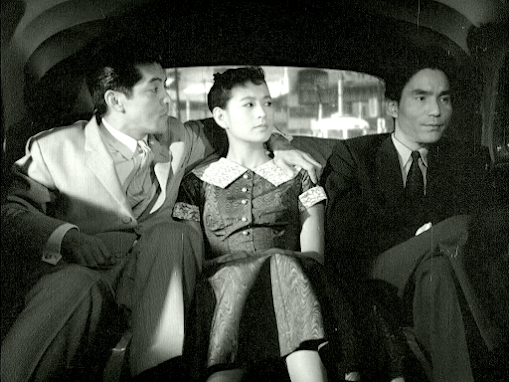

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi Uno

Rentaro Mikuni, Mie Kitahara and Jukichi UnoTamiko (Mie Kitahara)is a young woman living at home with her stepmother, Nobuko (Yumeji Tsukioka),and her bedridden brother, Junjiro (Nobuo Kaneko). Tamiko’s parents are bothdeceased and she’s approaching the usual age for marriage, so candidates arebeing discussed. Her father had wanted her to marry Komatsu (Jukichi Uno), aneasygoing nice guy who works in a munitions factory, but she’s not attracted tohim. Tamiko prefers the more aggressive and ambitious Ihara (Rentaro Mikuni), amedical doctor who spends most of his time experimenting on animals when he’snot womanising. However, she mistakenly believes that Nobuko wants him forherself, and this becomes a major source of friction between the two women.Meanwhile, Junjiro – who has never got over the fact that his wife left him –is becoming increasingly obsessed with investing in stocks and shares…

Yumeji Tsukioka

Yumeji TsukiokaThis Nikkatsuproduction was based on an untranslated 1955 novel of the same name by the left-wing writer TatsuzoIshikawa (1905-85), whose work was also to provide the basis for several SatsuoYamamoto films, including The Human Wall(1959). Ishikawa had actually been imprisoned by the Japanese authorities for afew months in 1938 as a result of his novel SoldiersAlive, which criticised the Japanese presence in China; he subsequentlyavoided such topics until after the war. AHole of My Own Making was adapted for the screen by Yasutaro Yagi, who hadwritten a number of scripts for this film’s director, Tomu Uchida, back in the1930s, before Uchida disappeared into Manchuria for a decade or so. The factthat Uchida chose to work with these two writers and that the resulting filmshows so little regard for commercial considerations (with the possible exceptionof its casting) leaves little doubt that it was a personal passion project and byno means a routine studio assignment.

Nobuo Kaneko

Nobuo KanekoLike Uchida’s previousfilm, Twilight Saloon, it also seemsto be something of an allegory for post-war Japan, perhaps most obviously inthe character of Junjiro, a disillusioned and broken man pursuing financialwealth for its own sake from his sickbed. However, despite the rich symbolismthat can be found throughout, I’ve seldom seen a film which leaves it so much upto the audience to decide how to feel about the characters, especially in thecase of Tamiko and Nobuko. Who exactly are we supposed to be rooting for here? It’sso unclear that it’s almost disorienting in comparison to the majority ofmovies, and it’s difficult even to be certain about which character is referredto in the title – a hole of whose ownmaking? Initially, I thought it must have been referring to Komatsu, who isintroduced at the beginning of the film sleeping in a drainage tunnel (?), but by the end Ithought it made more sense referring to Tamiko… Anyway, I personally enjoyed the film’s ambiguity, though I can imagine that some might feel exasperated and lose patience.

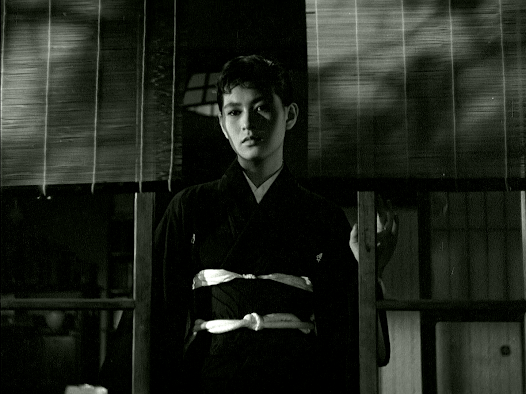

Mie Kitahara

Mie KitaharaEven moreunconventional is the harpsichord score by Yasushi Akutagawa (son of Rashomon writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa!),which at times sounds like it's being played by a demented chimp. Weirdly, I kind of liked this too, andyou certainly can’t accuse anyone of going for the obvious here. Talking ofmusic, Nobuko and Ihara attend a kotoconcert around half an hour in, and the blind musician we see performing is quitesomething. He is Michio Miyagi (1894-1956), one of the all-time greats oftraditional Japanese music.*

Michio Miyagi

Michio MiyagiThe actors are all wellcast and the performances solid all round. Mikuni dissects a live frog at onepoint, and doesn’t appear to have faked it – unsurprising as he was known fortaking realism to extremes. The point was presumably to underline the character’slack of feeling, but I have to say that I thought it was unnecessary.

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-star

Mikuni with another unfortunate co-starTo return to the film’suse of metaphors, a new sports centre is being built outside Tamiko’s familyhome, and construction noises are audible in every daytime scene set in thatlocation – clearly a deliberate if unusual choice, and one that I think was intendedto suggest that the old way of life is coming to an end. As in therecently-reviewed film A Rainbow at EveryTurn (1956), military jets fly over in several scenes, including right at the end,implying an uncertain future not just for Tamiko and what’s left of her family,but for the Japanese people as a whole. But Uchida never represents hischaracters in this film as simple victims of change – many of them areunlikeable and are pursuing selfish goals, and in various ways they bring theirmisfortunes on themselves. Perhaps the title refers to more than one of thecharacters after all, and of course it could be taken to refer to the Japanese nation as a whole, so A Hole of Our Own Making might have been a better fit.

*Despite his blindness, Miyagi also composedthe score for a 1935 version of PrincessKaguya photographed by special effects whiz Eiji Tsuburaya. A shortenedversion (33 minutes instead of the original 75) was rediscovered in the UK in 2015.An excerpt can be viewed on YouTube here.

Thanks to A.K.

For more on A Hole of My Own Making, click here.