M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 12

April 11, 2024

Girls in the Orchard / 花の中の娘たち / Hana no naka no musumetachi (1953)

Obscure Japanese Film #109

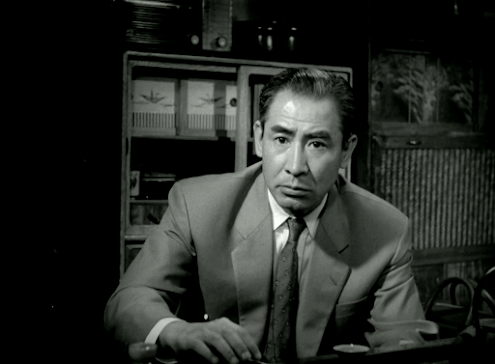

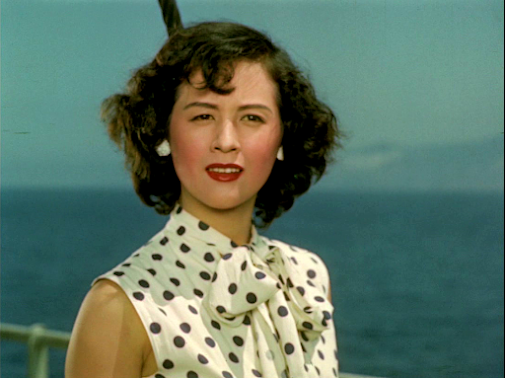

Mariko Okada

Mariko OkadaToho’s first featurefilm in full colour concerns the Ishii family, who live in the rural area ofKanagawa, an hour away from Tokyo by train. The head of the household, SaheiIshii (Makoto Kobori), grows pears and takes great pride in his work,stubbornly refusing to take the easy option and sell his land for what would bea considerable profit. It is assumed that his eldest son, Seitaro (Kiyoshi Kamoda),will inherit the land and continue the family business.

The older of Sahei’stwo daughters, Yoshiko (Yoko Sugi), commutes to Tokyo, where she is employed ata hotel with hideously garish décor presumably designed to show off the newFujicolor process. She has a boyfriend, Junichi (Hiroshi Koizumi), who works atthe hotel as an electrician, but he’s been offered a better job in far-offOkinawa and wants her to join him.

Yoshiko’s youngersister, Momoko (Mariko Okada), is rather bored with country life and dreams ofthe bright lights of Tokyo. She’s also starting to become interested in theopposite sex so, when Kitakoji (Akihiko Hirata), a music student from thecapital, moves in next door, she quickly falls in love with him and his fancyTokyo ways. Then Seitaro gets hit by a truck and dies, so Sahei puts pressureon Yoshiko to marry Katsuzo (Keiju Kobayashi), a young local whose onlyambition is to grow pears…

This is a veryconservative film whose drama revolves around the classic Japanese formula of giri (obligation) versus ninjo (inclination), especially in thecase of Yoshiko, who feels a strong sense of duty towards her family but wantsto go off to Okinawa with Junichi. The film also pits the countryside againstthe city. Ultimately, giri and thecountryside win – almost nobody gets what they thought they wanted, but it allworks out alright in the end. Wanting to go off to Tokyo is seen as youthfulfolly, i.e. something the young naturally have to get out of their systembefore they can become sensible and mature human beings. The roles of the twosisters are reversed at the end when Momoko gets a job in Tokyo, but there’s asense that sooner or later she’ll become disillusioned with city life andreturn to Kanagawa.

There’s also a subplotinvolving a Japanese-American woman at the hotel who is married to an Americanthe cops want to arrest for fraud. This distrust-of-the-foreigner element maybe partly due to the fact that the American occupation had ended the yearbefore, so Japanese filmmakers were now free to be critical of the Americans again.However, Toho rather wants to have its cake and eat it on this point, as themusic score by Raymond Gallois-Montbrun could hardly be less Japanese andsmacks of Hollywood.

Despite itsquestionable ideology, Girls in theOrchard is not without its charms, and most of the characters – which alsoinclude Eijiro Tono as a drunken uncle – are likeable and easy to care about.The success of the colour process is difficult to judge given the poor qualityof the copy I watched, but it’s certainly not one of the more subtle uses ofcolour I’ve seen.

Girlsin the Orchard was co-written and directedby Kajiro Yamamoto (1902-74), a director whose name has survived mainly as afootnote; he was Akira Kurosawa’s mentor, and few of his own films are easilyaccessible today.

Bonus trivia: The filmcontains an early example of blatant product placement in a couple of scenesfeaturing Lion toothpaste, a Japanese brand.

Note on the title: The Japanese title translatesmore accurately as ‘Girls in Blossom’ (although another possibility would be ‘BloomingGirls’, which of course is much better).April 5, 2024

Break Down That Wall / その壁を砕け / Sono kabe o kudake (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #108

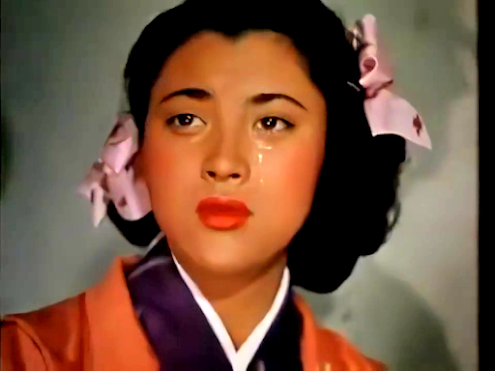

Izumi Ashikawa and Yuji Odaka in foreground

Izumi Ashikawa and Yuji Odaka in foregroundSaburo (Yuji Odaka) isa young Tokyo garage mechanic who has been working hard and saving diligentlyfor three years in order to buy a car and get married. His fiancée, Toshie(Izumi Ashikawa), is a nurse in Niigata. Feeling full of himself, Saburo drivesthrough the night in his new car to join her, and passes through a villagewhere someone has just been murdered in the course of a burglary. This bad timing leads to him being pulled over and arrested by ambitious local cop Moriyama (Hiroyuki Nagato).Unfortunately, Saburo's luck takes a further turn for the worse when he’s taken tothe scene of the crime and identified as the culprit by the murdered man’s wife(Mrs Koreya Senda, Teruko Kishi), who is still suffering from concussion.

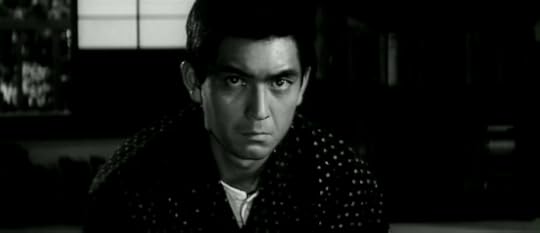

Although it seems thatSaburo will be the protagonist of the story, he largely disappears once he getsthrown in jail, and the focus shifts onto Moriyama, who turns out to have alittle more depth than we first suspect. (This is good news for the viewer as he’s a moreinteresting character, and Hiroyuki Nagato – perhaps best known for playing thelead in Pigs and Battleships – is alsoa more interesting actor.) However, Moriyuma’s colleagues are less sensitiveindividuals and it’s not the first Japanese film I’ve seen in which most of thecops are more interested in saving face than getting the right man. It’s evenimplied they would lose their jobs if found to have made a mistake. Does thisreflect reality or is it dramatic license? I’m not sure. In any case, theapparently simple story goes off in some unexpected directions, with Moriyamamaking a trip all the way to Sado island at one point to see Sakiko (MisakoWatanabe), a woman for whom he seems to have had romantic feelings, but who haseloped with a labourer (Shigeru Koyama in an early appearance).

Working from anoriginal screenplay by the unstoppable Kaneto Shindo, director Ko Nakahira pullsoff an excellent chase sequence involving a train and, while the film’s finaleis not much of a surprise, also manages to avoid a clichéd ending, making it farmore memorable than it might have been.

Ko Nishimura and Izumi Ashikawa

Ko Nishimura and Izumi Ashikawa

A Nikkatsu production, the film alsobenefits from an effective music score by Akira Ifukube and the stylish noircamerawork of Shinsaku Himeda, as well as a strong supporting cast whichincludes Ko Nishimura as Moriyama’s boss, Kinzo Shin as a judge and HidejiOtaki in a tiny role.

March 28, 2024

A Story from Echigo / 越後つついし親不知 / Echigo Tsutsuishi Oyashirazu (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #107

Rentaro Mikuni and Yoshiko Sakuma

Rentaro Mikuni and Yoshiko Sakuma

In 1930s Japan, Gonsuke(Rentaro Mikuni) is working at a sake brewery in Fushimi, Kyoto when hereceives news that his mother is seriously ill. He is given compassionate leaveto return to his village in Echigo (a former province in the snowy area ofnorth-central Japan now known as Niigata Prefecture). As a colleague of Gonsuke’snamed Tomekichi (Shoichi Ozawa) is from the same village, Gonsuke asks him ifhe has a message for his wife, Oshin (Yoshiko Sakuma). Tomekichi asks him totell Oshin that he’s just been promoted. This is news to Gonsuke, who wasalready jealous of Tomekichi’s marriage to such an attractive woman as Oshinand is now doubly displeased to hear that he’s been passed over for promotionin favour of Tomekichi.

On his way home,Gonsuke stops off at an inn, where he falls into conversation with a fellowcustomer (Eijro Tono) who it turns out used to be in the army with Gonsuke’selder brother. This lascivious old man tells Gonsuke tales of the brother’smany sexual conquests while they were stationed in Russia together. Gonsukegets drunk with him before leaving and begins to brood about his own lack of asex life before completing his journey home. When he’s nearly reached thevillage, he encounters Oshin walking home alone from her job weaving tatamimats. He makes a clumsy pass at her but, finding himself rejected, herapes her in the snow.

While Gonsuke wascommitting this crime, his mother was dying; when he gets home, it’s alreadytoo late. However, he seems not only indifferent to her death, but actuallyfull of himself for having managed to have his way with Oshin when there wasnobody around. After his mother’s funeral, he visits her and again makesadvances but is again rejected. His vanity wounded, he decides to get revengeby telling Tomekichi that Oshin is having an affair with the foreman at herworkplace (Kei Sato)…

If that partialsynopsis rings a bell, that’s because this is a clever recycling of Othello – the setting and thepersonalities may be considerably altered, but essentially Gonsuke is Iago,Tomekichi is Othello, Oshin is Desdemona and the foreman is Cassio. Due to the waythe plot unfolds, it’s clear that this is no coincidence, especially if we takeinto account that the film was based on a 1962 novel by Tsutomu Mizukami (orMinakami), who would certainly have been familiar with the major plays ofShakespeare. Mizukami was a fine writer whose other filmed novels include The Temple of Wild Geese, Bamboo Dolls of Echizen, Straits of Hunger (aka A Fugitive from the Past) and Lake of Tears (also starring YoshikoSakuma). I recommend the Dalkey Archive’s English translation of The Temple of Wild Geese and Bamboo Dolls of Echizen in one volume ifyou can find it.

The great thing aboutthis kind of story is that it could happen to people of any era or country, soit has not dated at all and probably never will (unlike some of directorTadashi Imai’s more topical pictures, such as Darkness at Noon, for example). Partly for this reason, A Story from Echigo may be his bestfilm, in my opinion (not that I’ve seen them all). Another reason is that theperformances from all three principles are outstanding. Rentaro Mikuni wasalways at his best in sleazy or unsympathetic roles, and he’s in his elementhere, utterly convincing as a vulgar man with zero morals or empathy, but whois, deep down, a sad and pathetic individual. Yoshiko Sakuma is every bit asgood playing the unfortunate victim of male lust and jealousy who does her bestto stand up to Gonsuke, but is ultimately placed in an impossible position.Sakuma has some arduous scenes in this film, and you really have to take yourhat off to her. This may well be her most impressive performance. Shoichi Ozawais perhaps better known for playing leading roles of a more comic type in filmslike Shohei Imamura’s The Pornographers(1966) and Yasuzo Masumura’s Chijin no ai(A Fool’s Love, 1967). In this more serious role, his characterchanges dramatically throughout the course of the film, and he portrays this metamorphosisextremely well. Eijiro Tono and Kei Sato make the most of their briefappearances, while the film also benefits from the presence of two wonderfulold pros, Taiji Tonoyama and Tanie Kitabayashi, as two of the village elders.

The story is strongstuff, and even contains a not-so-subtle hint of necrophilia at one point,resulting in the film receiving an ‘Adult’ classification for its originalrelease. At the time it was made, Toei (the studio responsible) were deliberatelyintroducing more sex into their films in an effort to entice people away fromtheir TV sets and back into the cinemas. According to Japanese Wikipedia, itwas Toei president Shigeru Okada’s idea to feature Yoshiko Sakuma in a more‘sexy’ role than she had previously played. Toei certainly promoted A Story from Echigo as an erotic film, thoughit’s hard to imagine anyone being turned on by anything in it. In any case,perhaps this element explains why such a fine film was largely overlooked asfar as awards go, scraping only a Mainichi Film Concours Best Screenplay award(shared with another film) for Yasutaro Yagi (1903-87, not 1906-65 as IMDbstates).

Composer Sei Ikeno andTadashi Imai’s frequent collaborator, cinematographer Shunichiro Nakao, alsodeserve a nod for their fine work on this great film, which has an ending thatis both devastating and perfect.

Note on the title: Inthe Japanese title, Echigo TsutsuishiOyashirazu, Tsutsuishi is the name of the village the principal characterscome from, while Oyashirazu refers to the Oyashirazu Cliffs in the same area.

Bonus trivia: Thevillage scenes were shot on location at Itoigawa in Niigata Prefecture.

March 22, 2024

Osho /王将 (‘King of shogi’, 1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #106

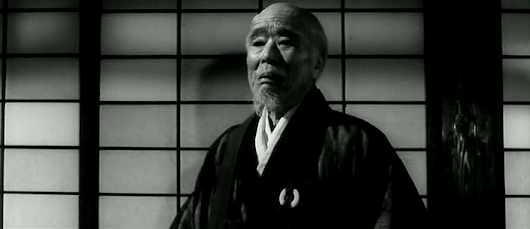

This Toei productionstars Rentaro Mikuni as Miyoshi Sakata (1870-1946), an illiterate sandal-makerwho went on to become the top player of shogi,a Japanese board game similar to chess. When we first meet him, he’s living bythe railroad tracks in the Tennoji area of Osaka around 1900, and he’s soobsessed with shogi that he neglectshis wife and children even when the family are struggling to get by. The onlythings that he can read are the characters on the shogi pieces.

He and his wife Koharu (Chikage Awashima) arefollowers of the Nichiren sect of Buddhism, but she is more devoted than he; inher despair, she frequently picks up an uchiwataiko (fan drum) and chants namu-myoho-renge-kyoin an effort to improve their karma (the unhappy wife who seeks solace inthis particular form of religion became something of a cliché in Japanese films and may well have originated in the 1947 play by Hideji Hojo uponwhich this film is based, although the real-life Sakata family were apparently notmembers of this sect).

After Sakata loses a game to Kinjiro Sekine (MikijiroHira) on a technicality, things get so bad that Koharu comes close tocommitting suicide on the railway tracks with their children. When her husbandrealises what he’s nearly driven her to, he throws his shogi board and pieces onto the tracks and vows to give up the gameforever. However, shortly after this occurs, a couple of shogi enthusiasts (Taiji Tonoyama and Norio Hanazawa) arrive,announcing they have decided to sponsor Sakata, and his career resumes. As theyears pass, he finds himself pitched against his arch-rival Sekine on a numberof further occasions, and gradually becomes the leading shogi player in the country, improving his family’s financialsituation in the process – but at what cost?

Taiji Tonoyama and Yoshiko Mita

Taiji Tonoyama and Yoshiko Mita

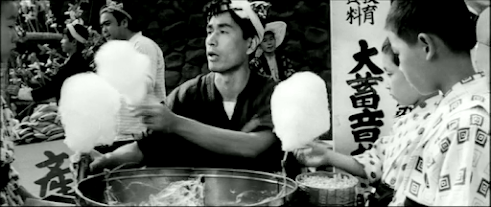

This was directorDaisuke Ito’s third go at this story. His first had been in 1948 withTsumasaburo Bando in the lead, and his second in 1955 with Ryutaro Tatsumi (whohad originated the role on stage). The film opens with an impressive crane shotof a bustling market lasting nearly two minutes and featuring hundreds ofextras (including Tetsuro Tanba as a candy floss seller at the very beginning!).

Ito is adept at the staging and blocking of scenes, and we are treated to somegreat camerawork throughout, while Akira Ifukube’s music is also effective. Thesets are extremely well-designed and detailed, even featuring a convincingreplica of the original Tsutentaku (a tower with neon lights) which overlookedSakata’s neighbourhood from 1912-43. However, Ito’s weakness, in my opinion,lies in his direction of actors, and he frequently allows or perhaps encouragesthem to go over the top, a flaw which is certainly evident here.

Tsutentaku, Mikuni and Awashima

Tsutentaku, Mikuni and Awashima

Rentaro Mikuni was ahighly talented actor, but also an eccentric. In Osho, he gurns and whines his way through his performance, hackingup phlegm and affecting a grating, high-pitched voice. The fact that Sakataalso gets physically violent with his grown-up daughter Tamae (Yoshiko Mita)when she tells him a few home truths means that he’s not only incrediblyirritating, but entirely unsympathetic too, and in my view this is highlydetrimental to the movie. Nevertheless, Mikuni seems to have had a hit in therole and appeared in a sequel (directed by Junya Sato) the following year(based on the play’s two sequels, I believe). It’s also worth noting that thereal Sakata was said to have been a dandy rather than the scruffy slob portrayedhere.

The rest of the castare generally fine, though even Chikage Awashima overdoes it at one point. AsSekine, Mikijiro Hira’s role feels underwritten and he’s left with little to do– presumably this part was beefed up a bit for Tatsuya Nakadai when heplayed the role in Hiromichi Horikawa’s 1973 remake opposite Shintaro Katsu(which, unlike this version, has Sakata suffering from an eye disease as he didin real life, possibly because Katsu had a knack for playing thevisually-impaired).

A young Sonny Chibaappears towards the end as one of Sakata’s disciples; the other is played byHideo Murata, who had scored a huge hit a year earlier singing a song alsoentitled ‘Osho’ and concerning the life of Sakata (perhaps it was that successwhich had led to this version).

If only Ito could havereigned Mikuni in a bit, this film might have been a true classic.

March 12, 2024

Shroud of Snow / 雪の喪章 / Yuki no mosho (1967)

Obscure Japanese Film #105

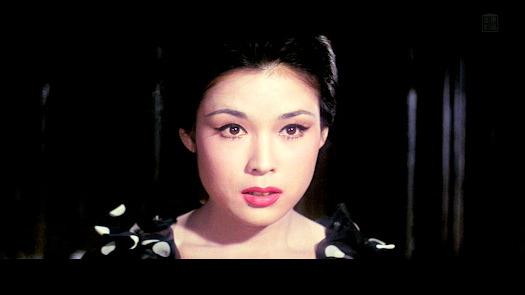

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoThestory begins in 1930 in Kanazawa, a city located on the west coast of Japan’smain island and known for its production of gold leaf and heavy snowfall inwinter. Taeko (Ayako Wakao) has just married into the Sayama family, who have asuccessful gold leaf business. Soon after the wedding, her husband, Kunio(Toyota Fukuda), hires a new maid, Sei (Tamao Nakamura), apparently in an actof charity as she’s an orphan and a distant relation of the family. Sei is of ameek disposition, so Taeko is profoundly shocked when she catches Kunio inflagrante with her. Kunio’s mother (Mitsuko Yoshikawa) apologises to Taeko onbehalf of her son, but explains pragmatically that it’s better than himspending his money in the red light district. However, Taeko finds herselfunable to forgive Kunio so, when one of her husband’s employees, Guntaro(Shigeru Amachi), confesses his love to her, she seems ready to run off toOsaka with him and start a new life.

WhenKunio discovers their plans, Guntaro ends up leaving without her, and Taekoseems to have little choice but to stay with her husband and try to make itwork. While resigning herself to her fate, she cannot help having vindictivethoughts, and when a series of tragedies occur – always during a heavy snowfall– she wonders if she has willed them into existence. As the years pass, thefamily’s fortunes take a dive, the war begins and events lead to an unexpectedreunion of sorts with Guntaro…

Revolvingaround the intertwined destinies of the four main characters, Shroud of Snow isnot so much the story of a love triangle, but a love square. Despite a number ofdramatic events, it’s a strange, enigmatic film in content as the real drama happensinside Taeko’s head. With no voiceover, the film relies heavily on the actingtalents of Ayako Wakao; fortunately, she’s adept at expressing the inner thoughtsand feelings of her characters, and gives her usual immaculate performance.Nevertheless, I’d love to be able to read the original novel in order tounderstand the film a little better, but unfortunately it’s never beentranslated and appears to be out of print in Japan.

Theauthor, Mitsuko Mizuashi (1914-2003), was herself from Kanazawa, where herfather ran a gold leaf business before going bankrupt, after which the familymoved to Osaka. Yuki no mosho, published in 1962, was her best-known work andthe only one to be filmed, although she was a well-regarded writer nominatedfor both the Akutagawa and Naoki prizes on several occasions. I suspect thatthe task of adapting her novel must have been challenging and may be why ituncharacteristically took Daiei five years to turn it into a film as well as the reasonit has not been filmed since.

Thedirector, Kenji Misumi, is well known for his Zatoichi and Lone Wolf and Cub films.Although Shroud of Snow is far from a typical Misumi film, his direction isimpressive while seldom calling attention to itself. He extracts goodperformances all round and pulls off some difficult shots wonderfully, such aswhen we see flakes of gold leaf swirling about in the smoke from a fire.Another plus is the score by Sei Ikeno, which is subtle and restrained yet makesthe most of the film’s dramatic moments.

Note on the title: A moreliteral translation of the Japanese title would be something like ‘SnowMourning Band’.

Bonustrivia: The gold leaf which covers Kyoto’s famous Kinkaku-ji (the Temple of theGolden Pavilion) was made in Kanazawa.

March 5, 2024

Forest of No Escape / 花実のない森 / Kajitsu no nai mori (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #104

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoUmeki (Keisuke Sonoi)is a car salesman who gives a lift to two women whose car has broken down. He’simmediately attracted by the beauty and well-dressed sophistication of one of hispassengers, Miyuki (Ayako Wakao), with whom he soon becomes obsessed, eventhough she’s clearly out of his league. After Umeki questions a hotel clerkabout her, he is approached by Hamada (Eiji Funakoshi), who invites him for adrink and confides that he is pursuing the same woman. The two men agree toremain friendly rivals and exchange information about Miyuki, who is extremelyreticent about her private life. It turns out that she lives with herhalf-brother, Hidemichi (Takahiro Tamura), who harbours an incestuous desirefor her. Umeki decides to install his current girlfriend, Setsuko (KyokoEnami), in their household as a spy by getting her to work as a maid there. Itbecomes apparent that there are other men in Miyuki’s life as well, and thefeelings of obsession and jealousy she inspires in the various men competingfor her attentions soon leads to murder…

Based on anuntranslated novel by Seicho Matsumoto, this Daiei production reunited starAyako Wakao with director Sokichi Tomimoto, with whom she had recently made Frolic of the Beasts. He does a decentbut unremarkable job, while Wakao is terrific as usual, especially in a scenein which she learns about a murder and you can really see the wheels turning inher head as she processes the information. It's a masterclass in reactive acting.

Keisuke Sonoi

Keisuke Sonoi

As the male lead, thelittle-known Keisuke Sonoi is competent but lacking in star quality, whileTakahiro Tamura is a little over-the-top at times as the jealous and possessive brother. Eiji Funakoshi, on the otherhand, hits the right note as a man who has completely given himself over to hisobsession, while behind the horn-rimmed glasses of Miyuki’s fashion-designerfriend lurks Rieko Sumi, aka Natsuko from Natsuko’sAdventure in Hokkaido (see previous review).

Eiji Funakoshi

Eiji Funakoshi

As Umeki's girlfriend, Kyoko Enami gives a strong performance in an underwritten role - she was soon to become a major star after Ayako Wakao hurt herself when she slipped in her bathroom and had to withdraw from the title role of Onna no toba (Lady Gambler), leaving Enami to step in and score a big hit which sparked a series of 17 films.

As one would expectfrom a Matsumoto story, there is a good twist at the end but, unfortunately,there is also some very lazy writing – we get zero explanation of exactly howUmeki manages to get Setsuko a job as Miyuki’s maid, for instance. It alsoseems as if we’re supposed to take Umeki’s behaviour – which we would callstalking today – as perfectly normal, and the ease with which people providehim with sensitive personal information about Miyuki is entirely unrealistic. Havingread a couple of books by Seicho Matsumoto (in translation), I wouldn’t be atall surprised if these weaknesses are present in the original, especially asscreenwriter Kazuo Funahashi, who also adapted Mishima’s Frolic of the Beasts and Tsutomu Mizukami’s Temple of Wild Geese, tended to be faithful to his literarysources as far as possible. It’s perhaps also worth noting that Daiei seemedto have a policy of restricting the running times of their films to around 90minutes, which would have made any extra exposition challenging.

Featuring what soundslike a musical saw, Sei Ikeno’s music is too often eccentric and distracting,although it does become highly effective at the end when events reach theirclimax. Overall, the film holds the interest fairly well despite itsunconvincing set-up, and it makes a pretty good vehicle for the great talent ofAyako Wakao, who also changes hairstyles and clothes numerous times throughout.

The Japanese title canbe translated as either ‘Forest without Flowers and Fruits’ or ‘Forest withoutSubstance’; in my opinion, the latter reading makes more sense. In either case,it’s a metaphor, so any tree fans out there may be disappointed to learn of theabsence of an actual forest.

Bonus trivia: In 1975, actor Keisuke Sonoi was sentenced to ten years inprison for tax evasion.

February 29, 2024

Natsuko’s Adventure in Hokkaido / 夏子の冒険/ Natsuko no boken (1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #103

Rieko Sumi

Rieko SumiNatsuko (Rieko Sumi) isa spoiled and stubborn young woman bored by the various men chasing her and thethought of becoming a housewife or socialite. Instead, she dreams of a man whopursues his passion no matter what obstacles he must face. Unable to find sucha person, she decides to become a nun, but on her way to enter a convent inHokkaido she takes the ferry and meets Tsuyoshi (Masao Wakahara). He’s a hunterreturning to the island to shoot the bear which, according to the subtitles,‘dismembered and killed’ his fiancée, Akiko (Keiko Awaji).

Convinced that she hasfinally found the man of her dreams, Natsuko abandons the idea of becoming anun and decides to follow Tsuyoshi and help him to kill the bear whether helikes it or not. When they reach Sapporo, Tsuyoshi tries to get rid of Natsukoby dumping her on his journalist friend, Noguchi (Teiji Takahashi), whopromptly falls in love with her. However, she proves impossible to shake off andfollows Tsuyoshi into the countryside to the house of Akiko’s father, Juzo(Takeshi Sakamoto), who accepts her as a guest.

Yoko Katsuragi and Takeshi Sakamoto

Yoko Katsuragi and Takeshi Sakamoto

Despite her efforts toassist Tsuyoshi in his quest, Natsuko proves more of a hindrance than a help,while Akiko’s younger sister, the 17-year-old Fujiko (Yoko Katsuragi), seems tohave become interested in Tsuyoshi herself and to regard Natsuko as a rival.Accustomed to rural life, Fujiko skips along the mountain trails with easewhile Natsuko can barely keep up. Meanwhile, Natsuko’s grandmother, mother andauntie (Chieko Higashiyama, Teruko Kishi and Sachiko Murase) want her back homeand are hot on her trail…

This Shochiku comedywas the second Japanese feature film in full colour. As the process was so newto Japan, some of the crew had to travel to Hollywood to get advice from theexperts there. Like many early colour films, subtlety was not the idea and thecostumes and backgrounds were designed to be as colourful as possible in orderto dazzle the cinemagoers of the day. Unfortunately, some brief parts of thefilm are missing, although the soundtrack is complete apart from one sequence;however, the vast majority of the film survives in excellent condition.

Natsuko’sAdventure in Hokkaido is a moderately amusing piece of fluff,so it’s something of a shock to see that it was based on a novel by YukioMishima, of all people. The book has not so far been translated into English, butit appears that the film is actually quite faithful and the novel is asimilarly lightweight piece. In the AsahiWeekly newspaper (29 July 1951), Mishima explained his motivation forwriting it. Here is a rough translation:

Although the story is set in Hokkaido, the main characters are young men and women from the city. However,in the city, young people cannot find anything worthy of theirenergy. They leave Tokyo with different dreams. I am dissatisfiedwith the fact that the current era does not provide the means of fulfillingyouthful dreams, so I wanted my characters to pursue their dreams amongthe lakes and forests of Hokkaido, where present-day Japan feels more likea foreign country.

Fans of the writerHaruki Murakami may also be interested to know that Mishima’s book is said tohave influenced Murakami’s novel A WildSheep Chase. Rieko Sumi

Rieko SumiAnother surprisingaspect of the film is that the star of this expensive production is notterribly well-known. Rieko Sumi (1928-2005) was from Hiroshima, where shesuffered exposure to the atomic bomb, though thankfully she made a fullrecovery and became the first Miss Hiroshima in 1948, leading to her beingsigned as a new face by Toho. Most of her leading roles were in the early ‘50s,after which she was mainly relegated to supporting roles. I felt that shefailed to give much depth to her portrayal of Natsuko, who comes across as alittle too unsympathetic, and perhaps that indicates why her career as aleading woman ended early. However, she contributed a moving cameo as an A-bombsurvivor who refuses to feel sorry for herself in Kozaburo Yoshimura’s A Night to Remember.

In Natsuko’s Adventure in Hokkaido, it’s Yoko Katsuragi who steals theshow as the coquettish Fujiko. Given that the film feels like an imitation ofthe Hollywood style even down to avant-garde composer Toshiro Mayuzumi’suncharacteristically conventional music score, it’s ironic that Fujikoexplicitly criticises Natsuko’s American values at the end of the film. As theAmericans had just left when the film went into production, perhaps thefilmmakers were unable to resist having a dig at their former occupiers even asthey continued to enthusiastically absorb their culture.

In regard to directorNoboru Nakamura, at this stage in his career he was just beginning to gain areputation as a reliable director of literary adaptations. On the basis of Natsuko’s Adventure, there’s little to distinguishhim from any other competent director, but his best work was yet to come infilms like Downpour (1957) and Koto (1963).February 21, 2024

Lake of Illusions / 幻の湖 / Maboroshi no mizuumi (1982)

Obscure Japanese Film #102

Reiko Nanjo

Reiko NanjoShinobu Hashimoto(1918-2018) had one of the most impressive track records in screenwriting,including as it did not just many of Kurosawa’s best films, but also othercast-iron classics such as Hara Kiri(1962) and Sword of Doom (1966),together with a long list of other excellent pictures. In 1973, he formed hisown production company, making two films in collaboration with Toho – Castle of Sand (1974) and Mount Hakkoda (1977) – both of whichwere big hits. These were followed by Villageof Eight Gravestones (1977) for Shochiku, an even bigger hit, so when heand his production company asked Toho to co-produce Lake of Illusions, which he would write and direct, he was in anexcellent position to get what he wanted and was given a free hand. AsHashimoto had also directed two previous features, they must have felt the riskto be minimal, and their optimism was such that the film was planned as Toho’s50th anniversary celebration work. However, they probably failed totake into account that many of Hashimoto’s previous screenplays had been written incollaboration with others (which he himself always maintained was the best way)or under the firm guiding hand of top directors such as Yoshitaro Nomura, MasakiKobayashi, Tadashi Imai, Kihachi Okamoto and others. Furthermore, Hashimoto wasan eccentric, as anyone who reads his book CompoundCinematics – Akira Kurosawa and I can easily see.

The genesis of Lake of Illusions is downright peculiar.As Castle of Sand had featured a lotof walking and Mount Hakkoda a lot ofmarching, he figured that it was time for a film with a lot of jogging. Accordingto Japanese Wikipedia, Hashimoto also wanted to develop a story which includedthree elements – an image of a woman in traditional Japanese dress plunging aknife into a man; a statue of Kannon, the 11-faced Bodhisattva of mercy,located near Lake Biwa; and, randomly, computer technology. He spent two yearsworking on the screenplay, but even he wasn’t convinced that he hadsuccessfully combined the three elements when the film went into production.

The central characteris Michiko, a 22-year-old woman who works in a weird theme hotel where she hasto dress in character as Oichi, a woman from the past who came to anunfortunate end (played by Keiko Takahashi in a flashback sequence). Michiko has no interest in history and is doing the job purelyfor the money and planning to leave as soon as she has reached her savingsgoal. Her main duties are actually providing baths and sex to wealthybusinessmen, something she finds tolerable as long as she’s ‘Oichi’ and notMichiko. She adopts a stray dog, whom she dubs ‘Shiro’, and goes for long runswith him along the shores of Lake Biwa on her days off, meeting a mysterious flute player (Daisuke Ryu) along the way. When Shiro is founddead from a head wound, she becomes obsessed with tracking down the killer andgetting revenge…

Hashimoto held openauditions for the part of Michiko. Out of 1,627 applicants, a young model namedReiko Nanjo was chosen, seemingly for her good looks, athleticism andwillingness to disrobe. Unfortunately, she had no real acting experience, andHashimoto was asking too much of a novice to carry the weight of such a hugepart in a major production. The film features endless scenes of Nanjo jogging –she reportedly ran 4,500 km while playing Michiko – as well as constantclose-ups of her, usually wearing the same sullen expression. Nanjo deservesrespect for her hard work but, in her hands, Michiko comes across as a bit of abrainless bimbo, which was presumably not the intention. Perhaps a moreexperienced director could have provided better guidance, but here she seemsover-exposed and under-directed, and she received poor reviews and few offers of work once the filmwas released. However, Akira Kurosawa (perhaps taking pity on Nanjo) gave her asmall part in Ran, and shesubsequently enjoyed a decade of modest success as an actress in TV dramasbefore quitting the entertainment industry and vanishing from public life.

On its release, thefilm was so badly received that Toho pulled it from cinemas two weeks afterrelease and effectively buried it. Shinobu Hashimoto’s magic touch had desertedhim and he suddenly found himself persona non grata with the film studios. It’snot difficult to see their point of view – Lakeof Illusions has a terrible script consisting of several disparate elementsclumsily cobbled together, even relying on two unlikely coincidences to patchup the deficiencies in its plot, like using sticking plaster to cover a woundwhen a transplant is called for. It also feels insanely long at over 2 hoursand 40 minutes, while the ending, which is akin to being catapulted into acompletely different movie, has to be seen to be believed.

With no TV broadcasts or VHS release, Lakeof Illusions was virtually impossible to see untilits eventual DVD release in 2003. It had come to be regarded as a legendarilybad film, but since then it has acquired a small cult following and has itsdefenders. While it does offer some incidental pleasures along the way, such asa chance to see the scenery around Lake Biwa, and a subtle music score byYasushi Akutagawa, in my opinion the film ultimately deserves its reputation asHashimoto’s grand folly, and his own verdict as expressed in Compound Cinematics is equally damning.

February 15, 2024

Sanshiro Sugata / 姿三四郎 (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #101

Yuzo Kayama

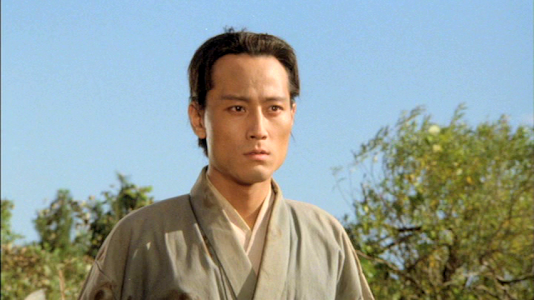

Yuzo KayamaAccording to StuartGalbraith IV in his book The Emperor andthe Wolf, this remake of Kurosawa’s debut film (about an early exponent ofjudo) and its sequel was motivated by the need to turn a quick profit after theinordinately lengthy and expensive production of Red Beard. However, this may not have been the only reason, as Sanshiro Sugata Part Two (1945) not onlycontained some badly dated anti-Western propaganda, but was actually considereda lost film at the time this remake was produced.*

In any case, Kurosawachose to co-produce the film, but not direct it, instead handing the reins overto the 42-year-old Seiichiro Uchikawa, who had been an assistant to animpressive range of directors, including Ozu, Kon Ichikawa, Hiroshi Shimizu andKenji Mizoguchi. He had found Mizoguchi extremely difficult and eventually beenfired by him after a dispute. Nevertheless, Uchikawa became a director himselfin 1953. By the time Sanshiro Sugatawent into production, he had already directed around 30 films – often also writingthe screenplays – and gradually built up a decent reputation without breakinginto the A-list. Most of these earlier films are inaccessible, the exceptionsbeing the two immediately preceding this one, namely Tange Sazen (1963) and Samuraifrom Nowhere (1964). The latter of the two was especially well-received andwas likely the reason why Kurosawa chose him as director of this remake. Unfortunatelyfor Uchikawa, Sanshiro Sugata wouldnot be received as positively, at least by the critics, and seems to havedamaged his career as he did not direct another feature film until 4 yearslater; when finally given another chance, he was reduced to making a vehiclefor the pop group known as The Tempters. In my opinion, that was unfair – whilethe remake lacks the panache that Kurosawa himself would no doubt have brought to it,in some ways it improves on the originals, benefitting from the use ofwidescreen, staging at least some of the fight sequences more effectively, and employinga stronger cast, and it’s certainly far more satisfying than Kihachi Okamoto’s1977 kiddie remake. Uchikawa was also somewhat straitjacketed by the obligationto follow Kurosawa’s blueprint, as Kurosawa made only minor changes to hisoriginals and even had Uchikawa replicate the montage of the abandoned geta.

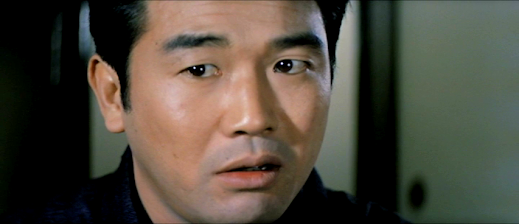

Kurosawa further puthis stamp on the film by filling the cast with his favourite actors. YuzoKayama (son of Ken Uehara) had just co-starred in Red Beard, and makes a good Sanshiro, being both convincing in thefight scenes and likeable in general. Toshiro Mifune is the perfect actor toplay his mentor, Shogoro Yano, and it’s great to see him kicking ass at thebeginning, hurling multiple assailants into a canal. Also ideal casting is BokuzenHidari as the comic priest who gives Sugata a hard time, while Yunosuke Ito andTsutomu Yamazaki make effective bad guys, and even Takashi Shimura pops up, althoughhis part is so brief it seems a mere token gesture. In the first film, Shimurahad played ju-jitsu master Hansuke Murai, the part played here by Daisuke Kato(surprisingly convincing as a formidable martial artist!).

Takashi Shimura

Takashi Shimura

Daisuke Ito and Eiji Okada

Daisuke Ito and Eiji Okada

Not Robert Shaw, but Eiji Okada

Not Robert Shaw, but Eiji Okada

From outside theKurosawa stable, Eiji Okada is impressive in a dual role as two of the brotherswho are Sugata’s most dangerous opponents (as karate master Tesshin, he looksremarkably like Robert Shaw). The female characters are played by less familiarnames – Yumiko Konoe is the love interest, while Chisako Hara** plays YunosukeIto’s vengeful daughter. Konoe’s main career has been as a singer, while Hara wasthe wife of director Akio Jissoji, and had a long career, but mainly playedsupporting roles in movies. Both are fine, but Hara has the more interestingrole even though it’s much smaller than Konoe’s.

Chisako Hara

Chisako Hara Yumiko Konoe

Yumiko KonoeThe high-contrastcinematography looks good throughout, while Yojimbocomposer Masaru Sato provides a score which, ironically, seems to be imitatingEnnio Morricone’s music for Sergio Leone’s unacknowledged Yojimbo remake, A Fistful ofDollars. The film’s main flaw is that it feels too long at two and a halfhours, but otherwise it’s hard to imagine it could have been much improved on bya director other than Uchikawa – unless, of course, it were Kurosawa himself,or perhaps Masaki Kobayashi. On the evidence of the film alone, it’s hard tosee why it should have been a career-killer for Uchikawa, although it’sentirely possible there are additional unknown factors which account for thesudden 4-year gap in his film career after this was released. Although thisfilm has been largely ignored by critics, its current of rating of 7.4 on IMDbstrongly suggests that most people who have seen it enjoyed it, and I wouldcertainly encourage anyone interested to check it out if you have the chance.

*A print wassubsequently discovered in Russia.

**Chisako Hara is listed as two separate people on IMDb.

February 9, 2024

Downpour / 土砂降り/ Doshaburi (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #100

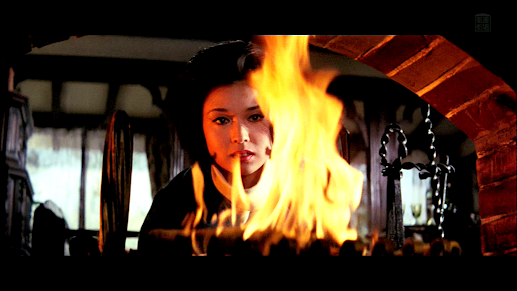

Mariko Okada

Mariko OkadaThis Shochikuproduction stars Mariko Okada as Matsuko, a young office worker in arelationship with a colleague, Kazuo (Keiji Sada). They’re a model couple andtheir boss approves of the match so much that he encourages them to getmarried. They agree, but there’s a problem – Matsuko has lied to Kazuo abouther background, saying that her father is dead and her mother runs an inn. Infact, her father (So Yamamura) is very much alive, but mostly absent becauseMatsuko’s mother, Tane (Sadako Sawamura), is actually his mistress.Furthermore, the inn she runs, where Matsuko also lives together with heryounger brother (Masami Taura) and sister (Miyuki Kuwano) is actually more likea love hotel, used by most of the guests simply as a convenient place for theirillicit liaisons. When the truth comes out, the young couple’s plans arederailed, leading to tragedy.

The subject matter of Downpour was considered risqué at thetime, and it received an adults-only classification as a result. Based on a1952 play by Hideji Hojo, it shows the devastating consequences that havingchildren by a mistress can have on those children. However, one of the strengthsof the film is its refusal to make a villain out of Matsuko’s father, Okubo.He’s portrayed as a decent man who is himself something of a victim here – bothof circumstances and of his own poor decisions. Perhaps the real cause of thetragedy that unfolds is not Okubo, but the judgmental nature of the societywithin which all of the characters are trapped. The inn where most of thefamily live is in fact hemmed in on one side by the railroad tracks, and steamtrains seem to be an important metaphor or symbol which runs throughout themovie, perhaps representing an unstoppable force which cannot be resisted, orpossibly a portent of doom.

The cast is uniformlyexcellent, and it’s especially satisfying to see the great Mariko Okada in a well-writtenrole which makes good use of her talent as the Matsuko we see towards the endof the film is very different from the one we saw at the beginning. Whilewatching, I thought that Shin Saburi was giving a surprisingly non-woodenperformance for a change, but then I realised it was actually So Yamamura.These two actors look so similar that I’m sure I can’t be the only one whoconfuses the two.

For me, this was astronger film from director Noboru Nakamura than the previously-reviewed Home Sweet Home or Portrait of Chieko, and the non-intrusive music by Toru Takemitsuand dark, shadowy cinematography of Hiroyuki Nagaoka were both excellentchoices.