M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 16

July 9, 2023

Revenge / 仇討/ Adauchi (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #68

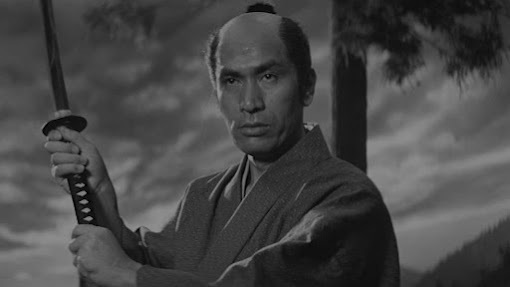

Shinpachi (Kinnosuke Nakamura) is a low-ranking samurai from a nevertheless prestigious family. His sense of pride has made him quick to take offence so, when a higher-ranking samurai (Shigeru Koyama) from the same clan criticises him for not taking sufficient care over the condition of the weapons, Shinpachi answers back and an argument begins which escalates into a duel. This first duel leads to further duels and Shinpachi finds himself increasingly backed into a corner when those in power decide to rig the game in order to suppress his protest once and for all.

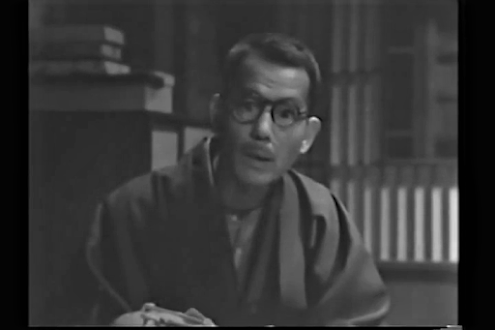

While less well-known overseas than Toshiro Mifune or Tatsuya Nakadai, Kinnosuke Nakamura was an equally big star in Japan. I find him more effective in some films than others, but he’s especially good as the mad Lord Horikawa in Portrait of Hell (1969) and he’s equally good here portraying another character whose sanity is questionable. While some may feel he goes over the top, for me his twitchy intensity suits the role perfectly.

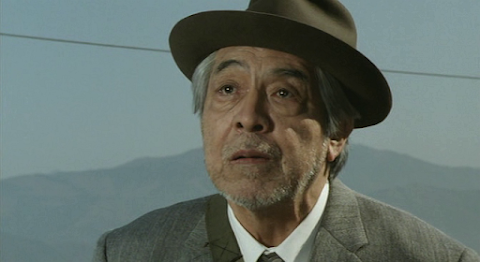

Tetsuro Tanba

Tetsuro TanbaThe other actors who make the most impression here are the always-reliable Masao Mishima as the sheriff who finds himself in a difficult position, Tetsuro Tanba as Shinpachi’s formidable second opponent, and, perhaps best of all, Eitaro Shindo as the rather worldly monk at whose temple Shinpachi takes refuge.

Of the eight films by director Tadashi Imai I’ve seen so far, this may be the strongest, but is certainly not the most typical. Imai made films in a wide range of styles and settings, but this work is reminiscent of the artistically-ambitious samurai films of Akira Kurosawa and Masaki Kobayashi – unsurprising as the original screenplay was written by Kurosawa favourite Shinobu Hashimoto, who also penned Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967). Hashimoto uses a complex flashback structure which works very well and lends a sense of inevitability to the tragic events which unfold.

The extras on the Eureka Blu-ray by Tony Rayns, Jasper Sharp and Tom Mes are all interesting and well-informed and avoid becoming too dryly academic. I had the impression that the film is generally seen as an attack on authority and the way it oppresses the freedom and dignity of individuals, and this theme certainly fits with Hashimoto’s scripts for Kobayashi. However, although this may well have been the intention, the character of Shinpachi is not terribly sympathetic and I felt that the film made a different point more effectively – the dire consequences which ensue as a result of Shinpachi’s refusal to ignore a criticism show the dangers of placing pride over pragmatism, and he is perhaps just as much at fault as the system he is caught up in.

Revenge also benefits from a strong score by Toshiro Mayuzumi, who on this occasion strikes a good balance between his desire to use modernist techniques and the necessity of serving the drama. The black-and-white ‘scope cinematography by frequent Tadashi Imai collaborator Shunichiro Nakao is also first-rate and looks great in Eureka’s release, as does the cover art by Tony Stella. One minor quibble, though – the cast list in the booklet only lists five of the actors, not even including Eitaro Shindo, who plays a major role in the film.

July 5, 2023

Home Sweet Home / 我が家は楽し / Waga ya wa tanoshi (1951)

Obscure Japanese Film #67

Isuzu Yamada and Hideko Takamine

Isuzu Yamada and Hideko TakamineThis Shochiku production stars Hideko Takamine as Tomoko, the eldest child of office worker Kosaku Uemura (Chishu Ryu) and housewife Namiko (Isuzu Yamada). As she has three younger siblings, there are a total of six members of the family living together. They are struggling to make ends meet on Kosaku’s modest salary, so Namiko works from home as a seamstress. A cheerfully self-sacrificing woman, she eats bread to save money while serving her family rice and never complains even though her slightly bumbling and absent-minded husband has not exactly set the world on fire.

Tomoko is in her early 20s and has ambitions to be a painter. Her fiancé, Saburo (Keiji Sada), is a war veteran with tuberculosis; she goes to visit him regularly in the sanatorium where he is a patient. Tomoko’s 18-year-old sister Nobuko (Keiko Kishi in her film debut) has started to become very popular with the local boys, something which causes some concern for her parents. Meanwhile, Tomoko feels she should probably give up painting and get a job to ease the financial burden on her family, but when Kosaku gets a bonus at work, it seems as if all their problems will be solved. However, just at the moment their hopes have been raised, they hit a run of bad luck and everything starts to go wrong…

Hideko Takamine and Keiko Kishi

Hideko Takamine and Keiko Kishi

Cinema audiences of the time must have related strongly to the problems faced by the Uemura family in a Japan that was yet to have recovered economically from the war. As portrayed here by a remarkable cast of then-present and future stars, the whole family are so likeable that you really feel for them when bad luck strikes.

This is the only film I’ve seen by director Noboru Nakamura (not to be confused with the more Roger Corman-like Nobuo Nakagawa!). Apparently, this was the first film of Nakamura’s to receive a considerable amount of positive attention from the critics of the day. I can’t say that I noticed anything exceptional in his direction, but the film compares well to similar domestic dramas by such filmmakers such as Ozu and Naruse – in fact, screenwriter Sumie Tanaka often wrote for Naruse – and I would certainly recommend it to anyone who enjoys their work.

June 30, 2023

Actress /女優 / Joyu (1947)

Obscure Japanese Film #66

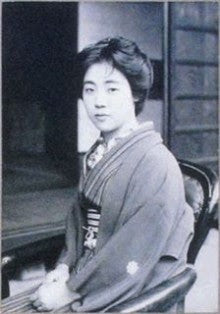

Isuzu Yamada

Isuzu YamadaSumako Matsui(1886-1919) was an actress who became the first major female star of shingeki,a Japanese theatre movement which sprung up in the late Meiji era and mainlystaged Western plays in translation without transposing them to a Japanesesetting. In other words, the actors would be dressed in Western clothes andoften blonde wigs to perform works by playwrights such as Ibsen andShakespeare. This may seem odd – after all, there’s no equivalent Westerntheatrical movement in which actors perform Asian plays in translation – but itshould be remembered that Japan had isolated itself for over 200 years prior tothe arrival of United States Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1853 (which led tothe Meiji Restoration of 1868), so it was a movement borne out of a naturalcuriosity about foreign culture. Before the emergence of shingeki, Japanesetheatre had consisted almost entirely of kabuki, Noh and bunraku, all of which had persisted for centuries with littlechange. The shingeki movement eventually came to include new works written byJapanese dramatists in a more realistic Western style with contemporaryJapanese settings. Unsurprisingly, during the war years, shingeki wassuppressed by the Japanese authorities as anti-patriotic, but when theAmericans occupied the country after the war, they actively encouraged itsrevival.

In 1947, Shochikustudios produced Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Love of Sumako the Actress starring KinuyoTanaka in the title role, while Toho produced this film about Sumako Matsui, directedby Teinosuke Kinugasa and starring Isuzu Yamada. That two rival companies hiton the same subject at the same time is probably not in this case because theythought a film about Matsui would be box office gold – after all, thepopularity of shingeki was largely limited to intellectual Tokyo-ites. The morelikely reason is that, during the American occupation, the film studios inJapan were restricted in their choice of subject matter, but could be sure ofenthusiastic approval for films which promoted Western values, as any story setin the world of shingeki was bound to do.

In Actress, we firstmeet Sumako when she is still going by her real name of Masako Kobayashi. Acountry girl with two failed marriages behind her, she joins a shingeki theatreschool but is not a good student at first – she snacks in class and doesn’t doher homework. However, after a stern reprimand, she changes her attitude andbegins to put more effort in than any of the others. This soon pays off and, muchto the disgust of the other female students, she is rewarded with the lead roleof Nora in A Doll’s House. She is a success in the part and grows close to herteacher, Hogetsu Shimamura (Yoshi Hijikata), who believes in her despite theattempts of Sumako’s fellow students to undermine her at every opportunity.Sumako and Shimamura begin having an affair, but tragedy strikes when he fallsill.

Kenji Mizoguchi’sversion of this story is one of his more minor works and he reputedly said thathe preferred Kinugasa’s longer film to his own. Running nearly two hours,Actress feels a little too long and the rather niche shingeki theme hasn’tdated terribly well. However, as a vehicle for Isuzu Yamada, it could not bebetter as we not only see her transformation from naive country bumpkin tosophisticated actress, but she gets to run the gamut of emotions and appear ina variety of stage roles as well. Yamada is excellent as always and is bettercasting in this role than Kinuyo Tanaka, being closer to the correct age andhaving a stronger resemblance to the real Sumako.

Director TeinosukeKinugasa is best known for A Page of Madness (1926) and Gate of Hell (1953).This is a lesser film – it’s well-made, but not exceptionally so, although itshould be remembered that Japanese directors were still working with limitedresources in 1947 and the quality of the country’s cinema would improvesignificantly over the coming years.

IMDb states thatKinugasa was at one time married to Isuzu Yamada, but this is incorrect–Kinugasa was married to someone else when he had an affair with Yamada whichlasted from 1946-50 and was therefore in progress during the making of thisfilm.

Among the supportingcast, the most familiar are the omnipresent Masao Mishima as a stagehand andTakashi Shimura in a very minor role as the owner of the building in which the schoolholds lessons.

Watch on YouTube (with imperfect subtitles).

June 26, 2023

Demon Statue/ 魔像 / Mazo (1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #65

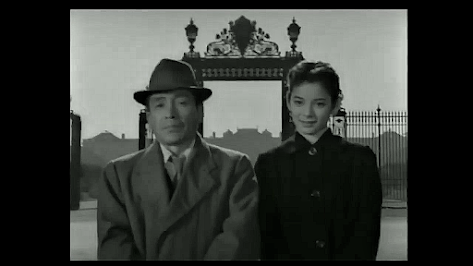

Tsumasaburo Bando and Isuzu Yamada

Tsumasaburo Bando and Isuzu YamadaThis Shochiku production is based on a popular story by the creator of Tange Sazen, Kaitaro Hasegawa (1900-35). Mazo was first published in 1930 under one of his pen-names, Fubo Hayashi, and the story has been filmed multiple times. Set in the mid-Edo period, it concerns Takanosuke Kamio* (Tsumasaburo Bando), who works as a guard at the castle and is disgusted with the corruption of his superiors. They also mock him as effeminate as he prefers to spend his time with his beautiful young wife, Sonoe (Keiko Tsushima).

One New Year’s Day, he is summoned to appear before them and the abuse goes further than usual, instigated by Omisuke Tobe (Mitsuo Nagata), who is jealous of Takanosuke as he had desired Sonoe for himself. He throws something at Takanosuke, gashing his forehead, and the group of 18 men bully him into making an apology for some imaginary transgression. Seated on the tatami, Takanosuke bows low and when he remains that way, Omisuke begins to shove him but is disconcerted when Takanosuke suddenly laughs in his face and walks out. Omisuke sees this crazed laugh as an insult and goes after him. Returning a while later, he drops dead in front of the others and they realise he has been slain by Takanosuke, who goes on the run. He falls in with a ronin, Ukon Ibara (Tsumasaburo Bando again), who looks just like him, and his wife, O-Gen (Isuzu Yamada). They also hate the corrupt officials and decide to help Takanosuke to get revenge on the other 17 men…

Given that an alternative translation of ‘mazo’ is ‘golem’, I had expected to see a monster made from stone or clay going on the rampage, but in that I was sadly disappointed. I can only assume that Takanosuke himself is the ‘demon statue’ in the sense that he is unflinching in his revenge. This story of rebellion has quite a lot in common with director Tatsuo Osone’s later Honno-ji in Flames, even down to the forehead-gashing suffered by the hero.

However, this is the lesser of the two works – it’s a smaller scale production and contains a surprising amount of comic elements, including the coquettish wife portrayed by Isuzu Yamada, who steals every scene she’s in.

If it seems hard to believe this is Lady Macbeth from Throne of Blood, after having seen at least 23 of her films by this point, I’ve been so impressed by her versatility that I’ve come to think of her as a sort of female Alec Guinness.

Tsumasaburo Bando is also good in two contrasting roles, but then he had certainly had plenty of practise as he had played them both twice before (see note below). He was one of those big stars of the era who is largely forgotten about now, perhaps partly because he passed away due to a stroke only one year after making this film. Also something of a revelation here is Masao Mishima, who appears in a role completely unlike any other I've seen him in and pulls it off nicely.

This is a well-made and enjoyable film, but ultimately an inconsequential one which never really rises above the level of entertainment.

*An alternative reading of Takanosuke Kamio is Kyounosuke Kajio. I’m uncertain which is correct.

Other versions:

1930 by Daisuke Ito starring Denjiro Okochi

1936 by Jun Ishigami also starring Tsumasaburo Bando

1938 by Hiroshi Inagaki also starring Tsumasaburo Bando

1956 by Kinnosuke Fukada starring Ryutaro Otomo

1962 as Chimoji yashiki ('Blood Letter

Mansion') by Eiichi Kudo starring Ryutaro Otomo

June 22, 2023

Will to Live / 生きたい/ Ikitai (1999)

Obscure Japanese Film #64

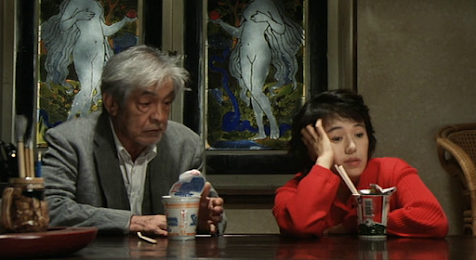

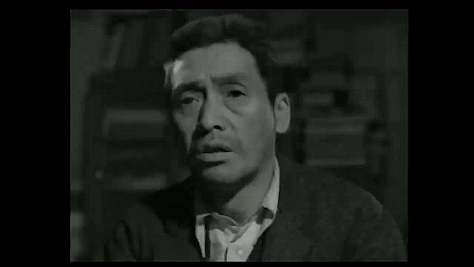

Rentaro Mikuni

Rentaro MikuniYasukichi (Rentaro Mikuni) is an ageing widower who can no longer control his bowels. He wants to continue living in his own house but is forced to consider moving to an old people’s home, partly out of consideration for his manic-depressive daughter, Tokuko (Shinobu Otake), with whom he lives. His situation leads to an obsession with a folk tale, The Legend of Mount Obasute, which tells of how the inhabitants of a remote mountain village used to abandon their elderly at the top of the mountain.

The Legend of Mount Obasute was the basis of the 1956 story 'The Ballad of Narayama' by Shichiro Fukasawa, filmed by Keisuke Kinoshita in 1958 and by Shohei Imamura in 1983. Both versions, though differing greatly in treatment, are masterpieces of Japanese cinema. In this later film, writer-director Kaneto Shindo has chosen to incorporate lengthy black-and-white sequences which retell the same story, so the parallels with Yasukichi’s situation could not be more explicit. I’m not sure we needed to see this story again, although the most memorable images in Will to Live come from these parts of the film.

Hideko Yoshida and Masayuki Shionoya

Hideko Yoshida and Masayuki Shionoya

In my view, the tone of light comedy which prevails in the rest of the picture seems inappropriate for the subject matter and prevents it from ever really becoming emotionally involving in the way it should have been. I was also unconvinced by the portrayal of what used to be called manic depression and is now known as bipolar disorder; admittedly I’m no expert, but in my limited experience based on people I’ve known, I think it usually manifests itself much more subtly than we see here.

I would recommend Masahiro Kobayashi’s Haru’s Journey and Japan’s Tragedy as being far more convincing and effective films on the theme of the problems of ageing in Japan.

June 18, 2023

Mount Hakkoda / 八甲田山 / Hakkado-san (1977)

Obscure Japanese Film #63

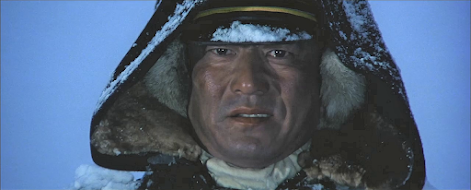

In the winter of 1901-02, a small squad and a larger regiment of soldiers try to find their way through the merciless Hakkoda mountains from opposite sides with the intention of meeting in the middle and establishing a new route to safeguard their supplies in the event of a Russian invasion. The two groups are led by Captain Tokushima (Ken Takakura) and Captain Kanda (Kinya Kitaoji); both men have the opportunity to decline the challenge but accept it against their better judgment due to fear of losing face. And so a tragedy is born out of the pride of men.

Ken Takakura

Ken TakakuraI’m fascinated by tales of survival and love films shot in rugged locations, so I thought this would be right up my street, but I was disappointed for a number of reasons. Although the location photography is indeed impressive (the actors and crew were working in incredibly harsh conditions), Mount Hakkoda unfortunately has little else to recommend it and is far too long and drawn-out. It’s basically three hours of men being stupid, and no opportunity for overacting is missed - except by Ken Takakura, of course, who was incapable of such a thing. Kinya Kitaoji and Rentaro Mikuni also put in decent performances, but too many of the others unnecessarily shout every line of their dialogue in a ‘WHAT I’M SAYING IS REALLY IMPORTANT!’ kind of way. Perhaps this is overcompensation due to the utter lack of memorable characters in the film. Some scenes are also completely unconvincing; in one unintentionally funny sequence, a soldier goes mad, strips off all his clothes and promptly drops dead. We are told that the sweat on his body instantly froze when he stepped outside the shelter and into the freezing air, and that this is what killed him. Yeah, right. Another character supposedly bites off his own tongue to commit suicide, something which I also doubt is possible. Such nonsense might be more forgivable were it not for the fact that this is based on a true historical incident. But we are in movie-land here, which is also made clear when Kumiko Akiyoshi turns up as a beautiful young villager who guides the soldiers part of the way, putting them all to shame as she skips effortlessly through the snow while the men struggle and gasp for breath behind her. Other members of the all-star cast, such as Keiju Kobayashi and Tetsuro Tanba, are wasted in nothing roles.

Kumiko Akiyoshi

Kumiko AkiyoshiYasushi Akutagawa’s music score is unsubtle, sentimental and repetitive, which pretty much sums up the movie as well. Shinobu Hashimoto produced and wrote this (based on a novel by Jiro Nitta) and it was directed by Shiro Moritani, a former assistant of Akira Kurosawa. Talking of Kurosawa, if he had directed it, he would no doubt have improved the script, made the characters more colourful, insisted on a better music score and made the whole thing a far more profound and resonant study of man’s folly.

June 12, 2023

Hateful Thing / 憎いもの / Nikui mono / (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #62

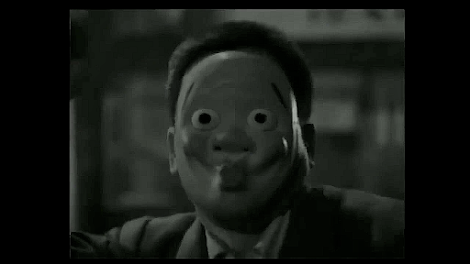

This Toho B-movie features Kurosawa favourite Kamatari Fujiwara in a rare leading role as Hikoichi, a meek and mild provincial who goes to Tokyo for the first time in 20 years in order to seek out cheap goods to sell in his store and also see his daughter, Yuko (Kyoko Anzai), who works in an office there and has been sending money home regularly. He is accompanied on his visit by Kiyama (Eijiro Tono), a fellow store owner who is more experienced and successful but has a less wholesome reason for visiting the capital. Hikoichi enjoys spending a day with his apparently unchanged daughter and the business side of his trip is also successful. When Kiyama insists that he join him on a visit to a brothel one evening, Hikoichi reluctantly agrees, although he declines to sleep with any of the young women available. However, while there he learns something that causes him a terrible shock and turns his life upside down…

Kamatari Fujiwara and Kyoko Anzai

Kamatari Fujiwara and Kyoko AnzaiAdapted by the great screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto from a short story by Yojiro Ishizaka, this is an effective little film with a cruelly ironic and rather unpleasant twist. While some of the early scenes may be on the bland side, this only serves to make the last third more unsettling. These latter scenes contain a number of memorable images, mainly involving the use of masks, and Fujiwara’s performance is especially good when Hikoichi finally turns from mild-mannered rube to violent avenger.

Kamatari Fujiwara (1905-85) remains best known as the untrusting farmer Manzo in Seven Samurai and the drunken kabuki actor in The Lower Depths. Although diminutive in stature, he is said to have had considerable martial art skills, which he once used to knock Toshiro Mifune to the ground during an argument when filming The Hidden Fortress. He later found himself in America appearing in Arthur Penn’s 1965 film Mickey One.

Eijiro Tono (another member of the Kurosawa-gumi) is one of those actors who appeared to enjoy playing repellent types and was very good at it, having the ability to speak as he does here in an incredibly grating voice. One particularly nice touch is when Hikoichi gets drunk after the shocking revelation and starts talking like Kiyama! Was this an imitation by Kamatari Fujiwara or was he dubbed by Tono? I would love to know. The cast of Kurosawa regulars is rounded out by Noriko Sengoku as a maid and Seiji Miyaguchi as a detective.

Director Seiji Maruyama would go on to be better known for his World War II films such as Admiral Yamamoto (1968) and Battle of the Japan Sea (1969).

Hateful Thing was the fourth in the ‘Toho Diamond’ series – these were stand-alone B-movies adapted from various literary works with running times of around an hour.

June 5, 2023

Goodbye, Hello / あなたと私の合言葉 さようなら、今日は / Anata to watashi no aikotoba sayōnara, konnichi wa (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #61

L-R: Hitomi Nozoe, Shin Saburi, Ayako Wakao and Machiko Kyo

L-R: Hitomi Nozoe, Shin Saburi, Ayako Wakao and Machiko Kyo

This comedy from Daiei studios stars Ayako Wakao as Kazuko, a modern young career woman working for Nissan Motors in Tokyo and living at home with her widowed father, Gosuke (Shin Saburi). Looking after him takes up much of her free time as he tends to come home drunk and is so useless in the kitchen that he can’t slice a lettuce without nearly severing a finger in the process.

Kazuko’s spoilt younger sister Michiko (Hitomi Nozoe) is no help in the house and is focusing on her new career as a flight stewardess. Kazuko has a fiancée, Hanjiro (Kenji Sugawara), but she seldom sees him as he is working in Osaka. The engagement is an arranged one and Kazuko’s heart is not really in it, so she decides to break it off. Her best friend, Umeko (Machiko Kyo), also lives in Osaka, where she runs a restaurant with her stepbrother, Torao (Eiji Funakoshi), who hopes one day to marry his stepsister. When Umeko comes to see Kazuko in Tokyo, Kazuko asks her to pay a visit to Hanjiro and cancel the engagement on her behalf, but when Umeko meets him, she falls for him herself. Meanwhile, Michiko has a crush on Tetsu (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), a young man who delivers the laundry and attends night school, but he is smitten with Kazuko, so it seems that everyone is in love with the wrong person…

Were it not for some quirky humour typical of director Kon Ichikawa, this could easily pass for a Yasuzo Masumura film and covers similar themes to Masumura’s Beauty is Guilty released the same year and featuring much of the same cast. Both films are concerned with the new possibilities which were opening up for women in Japan at the time and both feature a modern, Westernised woman (played by Ayako Wakao) contrasted with a more traditional counterpart who dresses in Japanese clothes (Machiko Kyo here, Fujiko Yamamoto in Beauty is Guilty) .

Machiko Kyo and Ayako Wakao

Machiko Kyo and Ayako WakaoGoodbye, Hello is also something of a twist on the films of Ozu in which Setsuko Hara ponders whether to leave home and get married or stay and look after widowed father Chishu Ryu. The ending of this film subverts the expectations that audiences would have had from familiarity with Ozu’s pictures.

Although it’s a minor work in the filmography of Kon Ichikawa, it’s certainly not without interest, especially as it features such a strong cast. Ayako Wakao and Machiko Kyo were paired by Daiei on quite a few occasions and clearly worked well together.

Kenji Sugawara, Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Eiji Funakoshi making their best drinking faces

Kenji Sugawara, Hiroshi Kawaguchi and Eiji Funakoshi making their best drinking faces

Hiroshi Kawaguchi is actually quite funny and likeable for a change; he married frequent co-star Hitomi Nozoe the following year. There’s even a brief appearance by a skinny young Jiro Tamiya right at the beginning (when he was still known by his real name, Goro Shibata).

The screenplay was co-written by Kon Ichikawa and his wife Natto Wada under their pen name of ‘Kurishitei’ in collaboration with Kazuo Funahashi. Some Japanese sources say that it had first appeared as a serialised novel. The Japanese title actually translates as The Password for You and I is ‘Goodbye, Hello’.

Watched without subtitles.

May 29, 2023

The Girl Who Tamed Beasts / 猛獣使いの少女 / Mōjūzukai no shōjo (1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #60

Chiemi Eri

Chiemi EriThis Daiei production stars the 15-year-old Chiemi Eri as Mayumi, a teenage circus performer employed by an American circus company visiting Japan. She is the child of a Japanese father and an American mother; when the war between the two countries began, her father was sent back to Japan not knowing that his wife was pregnant. Mayumi’s mother died not long after giving birth to her and she was she was brought up by the kindly Kosuke (Minoru Chiaki), who works as a clown in the same circus. In an interview for a Japanese newspaper, Mayumi mentions that she hopes one day to find her real father, Sokichi (Joji Oka). Fate brings them together, but Sokichi is ashamed of his humble status as a street musician and struggles with the question of whether he should reveal his identity to his daughter…

Minoru Chiaki

Minoru ChiakiThis is definitely a film for circus buffs, featuring as it does plentiful footage of the real-life E.K. Fernandez All American Circus (founded in 1903 in Hawaii) which travelled internationally. Presumably, some bright spark at Daiei learned that the circus were visiting Japan and saw an opportunity to create a vehicle for teenage singing sensation Chiemi Eri, whose first film this was. Eri proved that she could act a bit too and immediately became a hugely popular film star as well.

Jun Negami and Ayako Wakao

Jun Negami and Ayako WakaoAppearing here in her second film is Ayako Wakao, then just 18. She plays a rather wholesome barmaid in a few scenes and is given nothing very interesting to do here, so there’s no indication that she would be a star only one year later.

Joji Oka

Joji OkaThe simple story cooked up by screenwriters Toshiro Ide and Umetsugu Inoue feels overstretched and the lion-taming climax is unconvincing (poorly-edited shots of a real tiger combined with shots of a stuffed animal), but otherwise this is a well-made film of some charm. What really saves it is the excellent performances of Joji Oka (star of Ozu’s Dragnet Girl) and Kurosawa favourite Minoru Chiaki as the two fathers – they actually manage to bring some gravitas to the lightweight material. The same cannot be said of the American who plays the circus manager, unfortunately – he gives quite the most wooden performance I’ve ever seen.

Wooden American guy

Wooden American guyThe Girl Who Tamed Beasts was directed by Kozo Saeki (1912-72), a Daiei contract director who helmed over a 100 films between 1937 and 1966, all of which appear to have fallen into obscurity.

For further information on the career of Chiemi Eri, and how her singing style was shaped by the post-war American occupation of Japan, see Michael Furmanovsky's article 'From Occupation Base Clubs to the Pop Charts: Eri Chiemi, Yukimura Izumi, and the Birth of Japan's Postwar Popular Music Industry'.

The Girl Who Tamed Beasts / 猛獣使いの少女 / Mōjūdzukai no shōjo (1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #60

This Daiei production stars the 15-year-old Chiemi Eri as Mayumi, a teenage circus performer employed by an American circus company visiting Japan. She is the child of a Japanese father and an American mother; when the war between the two countries began, her father was sent back to Japan not knowing that his wife was pregnant. Mayumi’s mother died not long after giving birth to her and she was she was brought up by the kindly Kosuke (Minoru Chiaki), who works as a clown in the same circus. In an interview for a Japanese newspaper, Mayumi mentions that she hopes one day to find her real father, Sokichi (Joji Oka). Fate brings them together, but Sokichi is ashamed of his humble status as a street musician and struggles with the question of whether he should reveal his identity to his daughter…

Minoru Chiaki

Minoru ChiakiThis is definitely a film for circus buffs, featuring as it does plentiful footage of the real-life E.K. Fernandez All American Circus (founded in 1903 in Hawaii) which travelled internationally. Presumably, some bright spark at Daiei learned that the circus were visiting Japan and saw an opportunity to create a vehicle for teenage singing sensation Chiemi Eri, whose first film this was. Eri proved that she could act a bit too and immediately became a hugely popular film star as well.

Appearing here in her second film is Ayako Wakao, then just 18. She plays a rather wholesome barmaid in a few scenes and is given nothing very interesting to do here, so there’s no indication that she would be a star only one year later.

The simple story cooked up by screenwriters Toshiro Ide and Umetsugu Inoue feels overstretched and the lion-taming climax is unconvincing (poorly-edited shots of a real tiger combined with shots of a stuffed animal), but otherwise this is a well-made film of some charm. What really saves it is the excellent performances of Joji Oka (star of Ozu’s Dragnet Girl) and Kurosawa favourite Minoru Chiaki as the two fathers – they actually manage to bring some gravitas to the lightweight material. The same cannot be said of the American who plays the circus manager, unfortunately – he gives quite the most wooden performance I’ve ever seen.

The Girl Who Tamed Beasts was directed by Kozo Saeki (1912-72), a Daiei contract director who helmed over a 100 films between 1937 and 1966, all of which appear to have fallen into obscurity.