M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 19

October 21, 2022

The Mysterious Edogawa Ranzan /怪奇 江戸川乱山 / Kaiki Edogawa Ranzan (1937)

Obscure Japanese Film #39

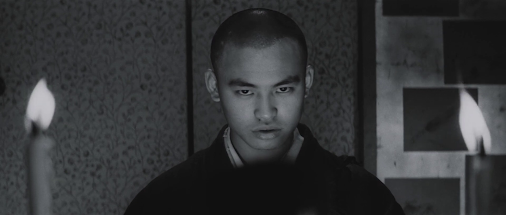

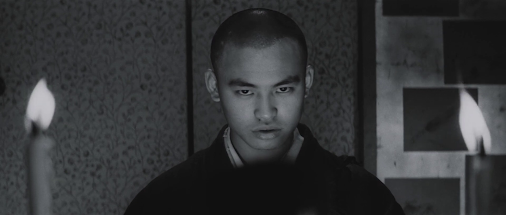

Ramon Mitsusaburo

Ramon MitsusaburoA samurai horror film from 1937, no less! Although clearly a minor work, this is certainly a fascinating curio, albeit one with a slightly misleading title – the picture has nothing to do with the famous Japanese mystery writer Edogawa Rampo (1894-1965), but the choice of the protagonist’s name was probably intended to make audiences believe that it did.

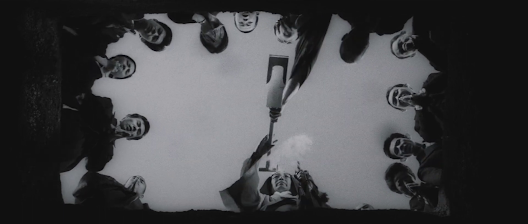

As the film begins, we see a man’s body being carried to an isolated house by an old geezer with a long beard and fingernails that would make Fu Manchu green with envy. He lays the body out on a table and performs a black magic ritual which revives the dead man. A turning waterwheel introduces a flashback sequence revealing that the man is a samurai named Edogawa Ranzan who was assassinated by henchmen of the local Mr Big. Needless to say, Ed wakes up in a foul mood and sets about revenging himself on those responsible, indulging in a blood-curdling laugh every time he dispatches another victim.

The story may be nothing to write home about, but there are some nice visual flourishes, such as a shot of a spider’s web which is refocused to resolve into a shot of Ed’s weeping fiancée, who has been abducted by Mr Big. Other visual elements such as shadows, swirling fog and tilting gravestones and streetlamps lend a suitably spooky atmosphere and suggest the influence of the Universal horror films of the early 1930s. However, the film does not quite live up to its opening and gets rather talky in the middle before recovering a bit in a couple of the later scenes, in which Ed makes a surprise attack through a ceiling and emerges from a swamp. The climax, though, feels somewhat fumbled and thrown away as if the filmmakers were running out of time and money, which perhaps they were.

While the picture quality remains surprisingly good, the same cannot be said of the crackly soundtrack. There were also a couple of abrupt and confusing cuts which made me wonder if the extant print could be missing a couple of scenes.

So, was this film a one-off or were other similar films produced in Japan at the time? Rather disappointingly, star Ramon Mitsusaburo (1901-76) proves not to have been the Japanese Boris Karloff, but a star of silent chambara (sword-fighting) films who by this stage in his career was a little down on his luck. The film was made for the short-lived Imai Eiga company, which cranked out a number of B-movies during its two years of existence (1937-8), many of them starring Mitsusaburo. However, judging by the titles, none of the others were horror films.

The film was written and directed by Kenji Shimomura (1902-93), a cinematographer-turned-director whose feature film career ended soon after this work, although he continued to make short documentaries into the 1970s. He deserves credit for bringing more visual flair to The Mysterious Edogawa Ranzan than is usually seen in such a low-budget programmer and even for venturing into the horror genre in the first place – this type of film only became popular in Japan around the mid-1950s and earlier examples are rare (with the exception of the many versions of The Ghost of Yotsuya).

Given the timing of the film's release, it's tempting to conclude that the story was intended as a metaphor about the need to revive Japan's warrior spirit. But then again, perhaps it's just a horror movie after all...

October 7, 2022

One Day at Summer's End / 濡れた二人 / Nureta futari (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #38

Ayako Wakao

Ayako Wakao

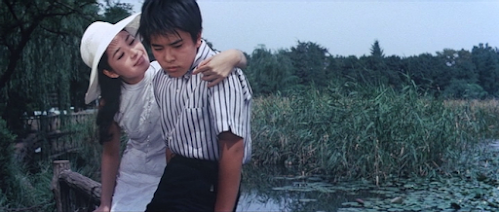

In the 19thof her 20 films for director Yasuzo Masumura, Ayako Wakao stars as Mariko, the frustrated wife of Tetsuya (Etsushi Takahashi), a salaryman who works long hours and spends little time at home. They plan a holiday away together, but it’s no surprise to Mariko when he decides he simply can’t afford the time off. She decides to make a solo trip to a fishing village in Izu to stay with Katsue (Hiroko Machida), who used to work for her parents but is now married with two young children. Mariko has barely got off the bus before she has attracted the attention of the local stud, Shigeo (Kinya Kitaoji) as well as the enmity of the local good-time girl, Kyoe (Mayumi Nagisa).

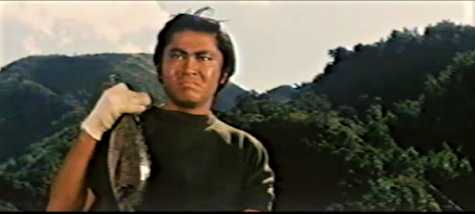

Kinya Kitaoji dangles his lady-bait

Kinya Kitaoji dangles his lady-bait

Shigeo’s seduction technique is to fling a large dead fish at girls he likes – it works with Kyoe, so he tries it on Mariko too, but she seems less impressed. However, she begins to feel lonely and Shigeo is the only one paying her any attention, so she gives into him after he’s slapped her around a bit and kicked sand in her face. Unfortunately, just as she’s begun enjoying gallivanting around the village with Shigeo, her husband unexpectedly turns up.

Having seen almost all of the Masmura-Wakao collaborations now, it’s hard not to feel that they should have called it a day after number 17 (The Wife of Seishu Hanaoka). The projects they worked on together after that are noticeably less ambitious, presumably because Daiei Studios was feeling the squeeze due to the increasing popularity of television in Japan at the time. One response to this was to make cheaper movies, while another was to provide content that TV could not – namely sex, violence and nudity. Both reactions are in evidence here. Wakao’s co-stars are less distinguished than usual and there’s little evidence of any significant amounts of money having been spent on the production. In fact, it all looks a bit cheap and hastily-shot, and further signs of desperation can be found in Mariko’s nude scenes, obviously achieved by means of a body double as her face is always conveniently obscured in these shots. One wonders whether Wakao even knew what they were up to.

Etsushi Takahashi and Ayako Wakao

Etsushi Takahashi and Ayako Wakao

Wakao is really the only reason to watch this and gives her usual excellent performance. Shigeo, with his greased-back hair, leather jacket and motorbike is so macho he seems absurd nowadays, especially as Kitaoji’s acting is nowhere near Wakao’s standard, at least at this stage in his career. Worse still, the film feels padded even at a slender 82 minutes, with Masumura having two very similar motorbike-race scenes close together, while a sequence in which Shigeo rides round and round Mariko and her husband at a bus stop in an effort to intimidate them goes on so long it becomes boring. While One Day at Summer’s End is not a terrible film, it’s not a good one either and I would probably rank it as the least of the Masmura-Wakao collaborations, although she does have a better role here than in some of the others.

The source of the simple story is a novel by Saho Sasazawa (1930-2002), a prolific writer of pulp mysteries who occasionally attempted something more serious; he also later played the heroine’s father in the bonkers horror comedy House (1977).

The Japanese title, Nureta futari, means 'The Two Who Got Wet', but ‘wet’ has a double meaning in Japan, so could equally be translated as ‘The Two Who Made Love.’

September 28, 2022

Feisty Edo Girl Nakanori-San / べらんめえ中乗りさん / Hibari minyo no tabi beranmee Nakanori-san (1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #37

Hibari Misora

Hibari MisoraOnly after watching this and doing a little research did I discover that Feisty Edo Girl Nakanori-San is the third in the series of five (I think) ‘Beranmee’ films. The first of these appeared in 1959 and is best-known in English as The Prickly-Mouthed Geisha (‘prickly-mouthed’ being a fair translation of the Japanese ‘beranmee’), while the final entry was released in 1963 under the title Beranmee geisha to detchi shachou (‘The Prickly-Mouthed Geisha and the Apprentice President’). However, it seems to matter little that I missed the first two as all are separate stories.

The film is a vehicle for Hibari Misora, one of Japan’s most popular stars of all time, but who remains little-known abroad. Born in 1937 as Kazue Kato, she became a star in late childhood, when she was given the stage name ‘Hibari’, meaning ‘lark’ (as in the songbird) due to her natural singing talent. As an actress, her abilities were a little more limited, but this did not prevent her becoming a major movie star. The film in question was made at the height of her popularity, when she was churning out almost one film a month for Toei Studios.

In Feisty Edo Girl Nakanori-San, Hibari stars as the daughter of a lumber company owner played by Isao Yamagata, probably best-known as Machiko Kyo’s kindly husband in Gate of Hell (1953), but later known for more villainous roles. Here, he is once more on the side of the angels and is also the best actor in the film. Hibari falls in love with the son of a rival company owner, a plot device harking back to Romeo and Juliet, which this movie explicitly references. The son is played by a gangly Ken Takakura, who stands a foot taller than Hibari and looks decidedly uncomfortable here before he had settled into the yakuza niche to which he was better suited. There are few surprises, although things become quite violent for such a piece of fluff, and basing it around the lumber industry certainly seems a novel choice. Otherwise, it’s business as usual, with the irrepressible Hibari bursting into song on several occasions – though I’m not sure I would call this a musical as there are no big Hollywood-style production numbers. Nevertheless, the film has its charms and anyone looking for light entertainment could do a lot worse.

Director Masamitsu Igayama, a former assistant to Tomu Uchida, left the movie business shortly after this film and worked in television until his retirement in 1982. He passed away in 2001 at the ripe old age of 96.

September 21, 2022

The Temple of Wild Geese / 雁の寺 / Gan no tera (1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #36

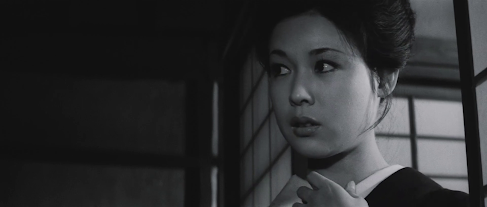

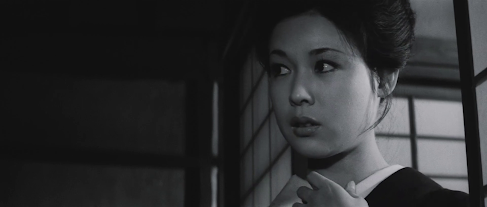

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoIn the second of her three films for Yuzo Kawashima (the others being Women are Born Twice and Elegant Beast), Ayako Wakao stars as Satoko, the mistress of Nangaku Kishimoto, a famous painter (Ganjiro Nakamura) who falls ill. When his friend Jikai, a Buddhist priest (Masao Mishima), comes to visit him on his deathbed, Kishimoto asks him to look after Satoko once he’s gone. The funeral soon follows, but Satoko is unable to attend for fear of scandal, so instead she visits Jikai’s temple a week later to burn incense in tribute. Jikai tells her of Nangaku’s last wish and forces himself on her. Satoko resists at first, but soon gives in and, for lack of a better option, goes to live with him at the temple. She endures Jikai’s embraces without complaint but soon begins to feel sympathy for Jinen (Kuniichi Takami), a young acolyte who works at the temple, where he lives in a tiny, cramped room resembling an animal’s cage and is treated like a slave by Jikai.

Masao Mishima gets some good news from Ganjiro Nakamura

Masao Mishima gets some good news from Ganjiro Nakamura

Set in Kyoto during the 1930s, the story is reminiscent of Yukio Mishima’s novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kon Ichikawa’s 1958 film version of which also featured Ganjiro Nakamura – although in that film it was he who played a randy and none-too-pious priest. Like the stuttering acolyte portrayed by Raizo Ichikawa in that film, Jinen secretly despises his master, whom he sees as cynical and corrupt. Kawashima’s film is an extremely faithful adaptation of a prize-winning 1961 novella by Tsutomu Mizukami, an author better known for his Seicho Matsumoto-like social crime thrillers such as Straits of Hunger (Kiga kaikyo), brilliantly filmed in 1965 by Tomu Uchida. The Temple of Wild Geese contains strong autobiographical elements as Mizukami himself had been harshly treated as an acolyte in his youth. However, the similarities to Mishima’s work are far from coincidental as Mizukami went on to write Gobancho Yugirirou, a 1962 novel inspired by the same incident (filmed by Tomotaka Tasaka the following year) and, in 1979, a non-fiction account of the case entitled Kinkaku enjo (The Burning of the Golden Pavilion).

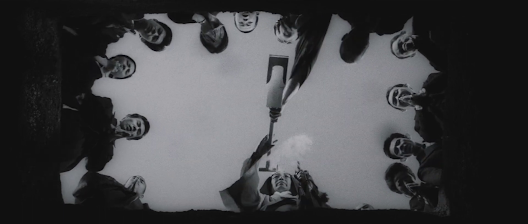

Kuniichi Takami

Kuniichi Takami

In an effort to avoid spoilers, I’ll just say that things get quite dark in this film until a jarring transition to colour at the end when Dixieland jazz bursts out on the soundtrack and we find ourselves in the present day as tourists visit the temple to see the famous paintings of wild geese by Nangaku which decorate the interior. The credits sequence at the beginning is also shot in colour and makes good use of the same paintings, but the rest of the movie is superbly shot in black and white by Sword of Doomcinematographer Hiroshi Murai, who comes up with some quite striking compositions. Sei Ikeno’s suitably ominous music score is also a plus.

Stout character actor Masao Mishima had perhaps his largest and best screen role here as the saké-guzzling, acolyte-abusing dirty old priest, and certainly makes the most of it. His incessant humming was an especially good touch, I felt, and in his hands Jikai comes across as even more despicable than he does in the book. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that the film’s release was the subject of indignant protests by many among the Buddhist community in Japan at the time. The star of the show, however, is Ayako Wakao, whose performance is flawless as usual. The role is an almost perfect fit for her, while the little-known Kuniichi Takami is also a good choice as Jinen, although he understandably lacks the slightly misshapen head of the book’s protagonist.

Wakao and Takami

Wakao and Takami

So, why, despite excellent work in every department, is the film somehow less compelling than it should have been? I think there are a number of reasons. Firstly, the story lacks an obvious central character with whom we can identify. Although Satoko is sympathetic, she’s so pragmatically accepting of her fate that it’s hard to relate to her, while Jinen, with his talk of the black kite that hides half-dead snakes, fish and rats in a hole at the top of a tree, in which they squirm around in a kind of hellish menagerie, is too creepy to win us over. I was surprised that Kawashima included this in the film but it’s quite well done. Although the pause button reveals the use of a puppet for the shot where the bird drops a snake into the hole, it’s not obvious when watching at normal speed. But it’s also an indication that this may be a rare case of a film being too faithful to its source for its own good. Kawashima shows little feel for pace, with some shots going on too long, while the music is used too sparingly and the final 15 minutes seem largely superfluous, especially the eccentric epilogue. Wakao’s big scene just before the prologue is a rare deviation from the novel, but one which seems completely over the top and was .obviously motivated solely by the desire to give the star a moment of high drama to go out on. Still, despite these quibbles, I consider The Temple of Wild Geese to be an unusual film of overall high quality which is well worth seeing.

The puppet shot

The puppet shot

The original novella is available in a fine English translation by Dennis Washburn published by the Dalkey Archive in 2008 in an omnibus edition with the same author’s Bamboo Dolls of Echizen (also turned into a film starring Ayako Wakao).

The Temple of Wild Geese / 雁の寺 / Gan no tera

Obscure Japanese Film #36

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoIn the second of her three films for Yuzo Kawashima (the others being Women are Born Twice and Elegant Beast), Ayako Wakao stars as Satoko, the mistress of Nangaku Kishimoto, a famous painter (Ganjiro Nakamura) who falls ill. When his friend Jikai, a Buddhist priest (Masao Mishima), comes to visit him on his deathbed, Kishimoto asks him to look after Satoko once he’s gone. The funeral soon follows, but Satoko is unable to attend for fear of scandal, so instead she visits Jikai’s temple a week later to burn incense in tribute. Jikai tells her of Nangaku’s last wish and forces himself on her. Satoko resists at first, but soon gives in and, for lack of a better option, goes to live with him at the temple. She endures Jikai’s embraces without complaint but soon begins to feel sympathy for Jinen (Kuniichi Takami), a young acolyte who works at the temple, where he lives in a tiny, cramped room resembling an animal’s cage and is treated like a slave by Jikai.

Masao Mishima gets some good news from Ganjiro Nakamura

Masao Mishima gets some good news from Ganjiro Nakamura

Set in Kyoto during the 1930s, the story is reminiscent of Yukio Mishima’s novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kon Ichikawa’s 1958 film version of which also featured Ganjiro Nakamura – although in that film it was he who played a randy and none-too-pious priest. Like the stuttering acolyte portrayed by Raizo Ichikawa in that film, Jinen secretly despises his master, whom he sees as cynical and corrupt. Kawashima’s film is an extremely faithful adaptation of a prize-winning 1961 novella by Tsutomu Mizukami, an author better known for his Seicho Matsumoto-like social crime thrillers such as Straits of Hunger (Kiga kaikyo), brilliantly filmed in 1965 by Tomu Uchida. The Temple of Wild Geese contains strong autobiographical elements as Mizukami himself had been harshly treated as an acolyte in his youth. However, the similarities to Mishima’s work are far from coincidental as Mizukami went on to write Gobancho Yugirirou, a 1962 novel inspired by the same incident (filmed by Tomotaka Tasaka the following year) and, in 1979, a non-fiction account of the case entitled Kinkaku enjo (The Burning of the Golden Pavilion).

Kuniichi Takami

Kuniichi Takami

In an effort to avoid spoilers, I’ll just say that things get quite dark in this film until a jarring transition to colour at the end when Dixieland jazz bursts out on the soundtrack and we find ourselves in the present day as tourists visit the temple to see the famous paintings of wild geese by Nangaku which decorate the interior. The credits sequence at the beginning is also shot in colour and makes good use of the same paintings, but the rest of the movie is superbly shot in black and white by Sword of Doomcinematographer Hiroshi Murai, who comes up with some quite striking compositions. Sei Ikeno’s suitably ominous music score is also a plus.

Stout character actor Masao Mishima had perhaps his largest and best screen role here as the saké-guzzling, acolyte-abusing dirty old priest, and certainly makes the most of it. His incessant humming was an especially good touch, I felt, and in his hands Jikai comes across as even more despicable than he does in the book. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that the film’s release was the subject of indignant protests by many among the Buddhist community in Japan at the time. The star of the show, however, is Ayako Wakao, whose performance is flawless as usual. The role is an almost perfect fit for her, while the little-known Kuniichi Takami is also a good choice as Jinen, although he understandably lacks the slightly misshapen head of the book’s protagonist.

Wakao and Takami

Wakao and Takami

So, why, despite excellent work in every department, is the film somehow less compelling than it should have been? I think there are a number of reasons. Firstly, the story lacks an obvious central character with whom we can identify. Although Satoko is sympathetic, she’s so pragmatically accepting of her fate that it’s hard to relate to her, while Jinen, with his talk of the black kite that hides half-dead snakes, fish and rats in a hole at the top of a tree, in which they squirm around in a kind of hellish menagerie, is too creepy to win us over. I was surprised that Kawashima included this in the film but it’s quite well done. Although the pause button reveals the use of a puppet for the shot where the bird drops a snake into the hole, it’s not obvious when watching at normal speed. But it’s also an indication that this may be a rare case of a film being too faithful to its source for its own good. Kawashima shows little feel for pace, with some shots going on too long, while the music is used too sparingly and the final 15 minutes seem largely superfluous, especially the eccentric epilogue. Wakao’s big scene just before the prologue is a rare deviation from the novel, but one which seems completely over the top and was .obviously motivated solely by the desire to give the star a moment of high drama to go out on. Still, despite these quibbles, I consider The Temple of Wild Geese to be an unusual film of overall high quality which is well worth seeing.

The puppet shot

The puppet shot

The original novella is available in a fine English translation by Dennis Washburn published by the Dalkey Archive in 2008 in an omnibus edition with the same author’s Bamboo Dolls of Echizen (also turned into a film starring Ayako Wakao).

September 12, 2022

Teigin Incident: Death Row Prisoner /帝銀事件 死刑囚 / Teigin jiken: Shikeishu aka The Long Death (1964)

Obscure Japanese Film #35

The debut film from director Kei Kumai (who also wrote the screenplay) is a docu-drama without stars which tells the true story of the Teigin Incident, one of the most notorious and bizarre crimes in the history of post-war Japan. On 26 January 1948, a man visited a bank in Tokyo just after closing time claiming to be an official from the health department. He informed the bank manager that he was there to protect the staff from an outbreak of dysentery in the area and it was necessary for them to take an oral vaccine. The manager gathered the staff together and the man demonstrated the correct way to take the medicine, apparently swallowing a dose himself to show that it was safe. The staff all took the ‘medicine’ together but within a very short time had been rendered helpless as a result of cyanide poisoning. The man stole 164,000 yen in cash and a cheque for 17,000 yen and left. He had even given a dose to the 8-year-old son of one of the staff, poisoning 16 people in total. Including the boy, 11 died at the scene, with one further victim expiring in hospital later. Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the crime was the calmness with which the man had carried it out – although there seems little doubt that he knew the poison would be fatal, the survivors said that his hands had not even trembled as he administered it.

The police arrested a painter named Sadamichi Hirasawa on suspicion of the murders. There were three main reasons for this: there was proof that he had been given a business card which matched the one that the man had presented at the bank but he was unable to produce it; he resembled the description given by the survivors; and he had recently deposited 130,000 yen into his bank account, but refused to reveal the source of his windfall. Hirasawa eventually confessed, but later withdrew his confession, claiming to have been coerced by the police under considerable duress. Doubts about his guilt were also fuelled by the fact that most of the witnesses could not identify him confidently. Nevertheless, the court found Hirasawa guilty and he was sentenced to death, although the sentence was never carried out and he was to die in prison in 1987 at the age of 95.

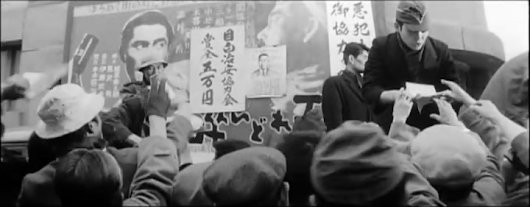

The Teigin Incident was a big news story in Japan in its day, and one which ran for a long time due to the numerous legal appeals and occasional uncovering of possible new evidence. It also gave birth to a number of conspiracy theories. Perhaps this explains why Nikkatsu Studios thought a film about the case may prove popular even without stars. Kumai clearly believed Hirasawa to have been innocent and was hoping to raise awareness about what he saw as a miscarriage of justice. Personally speaking, from what I’ve read about the case, I believe he was probably guilty. One theory as to why he would not explain the source of his bank deposit is that he had been earning money by painting pornographic pictures and was ashamed to admit it; in my view, it’s difficult to believe that he would not have owned up to that under the circumstances. It would be a strange person indeed who would prefer to be thought guilty of murdering 12 people including a child rather than be exposed as a clandestine painter of lewd pictures. It is also worth noting that some of the works of respected Japanese masters such as Hokusai and Kyosai were pornographic in nature, so would this really have been considered such a shameful thing to have done? Furthermore, Hirasawa’s alibi was that he was walking close to the scene of the crime at the time; considering he had lived in that area in the past but was at that point living in Hokkaido, this must be the world’s worst alibi.

Kumai chooses not to focus on any one character; instead, he concentrates his attention on details of the investigations by both the police and the press. He frequently crams the frame with large groups of policemen and journalists (often seen fanning themselves or wiping the sweat from their necks), painting a picture of post-war Tokyo as a hot, overcrowded and oppressive place just as he would in his later film Wilful Murder (1981), which has a great deal in common with this one. Wilful Murder differs in approach mainly in giving us a central character to identify with (the crusading journalist played by Tatsuya Nakadai) and is arguably more engaging for that reason. Kumai works hard to make his film more than a compilation of scenes of men explaining stuff by throwing in a couple of fights and generally keeping things moving as much as possible. His next film, A Chain of Islands, covered similar ground but used a fictional story, and he would go on to expose other incidents he viewed as injustices his country had tried to sweep under the carpet in a number of future works, such as Sandakan No.8 and The Sea and Poison.

Teigin Incident: Death Row Prisoner is a rather talky picture that tells a complex story, but it’s certainly well-made and features an effectively ominous score by Godzilla composer Akira Ifukube and atmospheric black and white camerawork by Umetsugu Inoue favourite Kazumi Iwasa. The large ensemble cast are mostly fine, while gaunt character actor Kinzo Shin nabs the key role of Hirasawa and portrays him with heartfelt sympathy as being unambiguously innocent. A familiar face from many Japanese films of the era, this was likely the highlight of his on-screen career.

Teigin Incident: Death Row Prisoner seems to have received some screenings abroad under the title The Long Death, but I was unable to find a subtitled copy.

August 31, 2022

365 Nights / 三百六十五夜 / Sambyaku-rokujugo ya (1948)

Obscure Japanese film #34

Hideko Takamine

Hideko Takamine

After making his feature film debut as director with the Shintoho production A Flower Blooms (1948) starring Hideko Takamine and Ken Uehara, Kon Ichikawa was assigned the task of directing another vehicle for the same two stars. He was handed a screenplay by Kennosuke Tateoka based on a 1946 novel by Masajiro Kojima (1894-1994) entitled 365 Nights. Although unimpressed with the script, he agreed in the hope that a studio-pleasing success would enable him to make a film version of Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story ‘In a Grove’, but he was to be disappointed in this as Akira Kurosawa pipped him to the post and used the story as the basis for Rashomon(1950). Ichikawa allegedly rewrote the screenplay for 365 Nights with his newly-wed wife Natto Wada while leaving Tateoka sole credit. However, in my view he failed to raise it above the level of melodramatic tosh and I lost count of the number of coincidences on which the overly-contrived plot relies.

Kawakita (Ken Uehara) is an up-and-coming young architect being relentlessly pursued by spoilt rich bitch Ranko (Hideko Takamine), who claims to love him for his ‘sincerity’ (this seems unlikely – the real reason is perhaps that he shows not the slightest interest in her). In order to avoid Ranko, Kawakita changes address, lodging with a middle-aged woman and her attractive daughter, Teruko (Hisako Yamane), with whom he quickly falls in love. However, the young couple’s hopes of marriage and future happiness are foiled by Kawakita’s old enemy, Tsugawa (Yuji Hori), an unscrupulous businessman who wants to marry Ranko and hates Kawakita partly out of jealousy, but mainly because the idealistic Kawakita regards him with contempt for his crass materialism.

Tsugawa is such a comic-book villain I’m sure Ichikawa would have had him twirling his moustache had it been longer, while the actions of Kawakita and Teruko are so foolish throughout that one soon loses patience with them. The fact that these three characters are so unrealistic makes it difficult to assess the abilities of Uehara, Yamane and Hori on this evidence. However, it’s no surprise that the best performance here comes from the great Hideko Takamine – as egotistical and arrogant as her character is, she at least resembles a real human being for whom it’s possible to feel some sympathy. It’s also Takamine with whom Ichikawa chooses to end the movie rather enigmatically practising golf. As this is a Western sport, it may be symbolic, especially as Ranko is always seen dressed in Western clothes, while Teruko – the embodiment of purity – is usually shown in Japanese dress. Takamine left Shintoho in 1950 and went freelance, but surprisingly never worked for Ichikawa again after 365 Nights.

For his part, despite his failure to rescue the script, Ichikawa does impress as a director, staging many sequences with considerable flair – there is a terrific prolonged fight scene when Kawakita confronts a burglar, for example, and he even breaks the rules by having Tsugawa rant directly to the camera at one point. Ichikawa is ably assisted by the fluid camerawork of Akira Mimura, although the music by Tadashi Hattori is cloying and has not dated well.

Like Ichikawa’s later picture, The Burmese Harp (1956), the film was originally released in two parts. The first half (set in Tokyo) appeared in cinemas on 21 September 1948, the second half (set in Osaka) a week later, running 78 minutes and 73 minutes respectively. The following year, a re-edited omnibus edition was released running 119 minutes – this is apparently the only version to have survived. Personally, I felt that this shorter version felt overlong, but then again sentimental tearjerkers of this type are not my favourite genre. However, 365 Nightswas very popular in its day and was remade in 1962 by director Kunio Watanabe with Ken Takakura as Kawakita and Hibari Misora as Ranko. On the whole, I would say that the original remains worth seeing for some interesting direction by Ichikawa and for Hideko Takamine.

Ichikawa himself did not count his earlier A Thousand and One Nights at Toho, made under a pseudonym.

Sometimes mistranslated as Seijiro Kojima

August 19, 2022

Night Butterflies / 夜の蝶 / Yoru no cho (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #33

Opening in documentary style as it takes us on a whistle-stop night-time tour around the upmarket bars of Tokyo’s Ginza district, Night Butterfliesfeatures intermittent narration by the world-weary Shuji (Eiji Funakoshi, best known for his leading role in Fires on the Plain), a failed musician turned ‘hostess-broker’. He finds bar hostess jobs for young women, many of whom have come to the capital due to the difficulty of earning a decent wage in the country. More spiv than pimp, Shuji treats the girls reasonably well and does not take advantage of them.

One of his best clients is Mari (Machiko Kyo), a bar owner from Osaka, where people are said to be more outspoken and down-to-earth than in Tokyo, and this is certainly true in her case. Mari’s bar is thriving, but she is displeased to hear the news that Okiku (Fujiko Yamamoto) has just arrived in the area and will shortly be opening a bar of her own. Okiku is originally from Kyoto, a city often seen as the polar opposite to Osaka and whose inhabitants have something of a reputation for pretentious and snobbish behaviour. The two women have a history revealed in black-and-white flashbacks – seven years previously, Mari had discovered that her late husband was cheating on her with Okiku. Initially, the two rivals are frostily polite to each other, but their mutual loathing simmers away beneath the surface before eventually boiling over, leading to tragedy.

Machiko Kyo and Eiji Funakoshi

Machiko Kyo and Eiji Funakoshi

Like the previously-reviewed Beauty is Guilty, Night Butterflies was based on a novel by Matsutaro Kawaguchiand adapted by Sumie Tanaka, although the two films seem to mark the extent of their collaborations. Director Kozaburo Yoshimura (1911-2000) was a well-respected filmmaker who specialised in drama but occasionally experimented with comedy, as in The Fellows Who Ate the Elephant (1947). An Osaka Story(1957) is perhaps the most impressive of his accessible films. While well-executed, Night Butterflies is interesting mainly for its story, subject matter and two female stars. Shot in academy ratio during the last days of that format in Japan before widescreen became standard, it left me feeling that the latter format usually makes for more arresting compositions even in dramas of this sort, despite Fritz Lang’s famous apocryphal quote that Cinemascope was only good for photographing funerals and snakes. If Yoshimura’s film had been shot in widescreen, it would closely resemble the work of fellow Daiei director Yasuzo Masumura, especially in its misanthropic outlook (although a Masumura version would probably have featured Shuji slapping the girls around and taking advantage of them).

There is one extremely jarring transition in the film – around 50 minutes in, we suddenly find ourselves observing a new character, a doctor (Hiroshi Akutagawa), squeezing blood out of a prostrate rabbit while his lab assistant fiancée (Mieko Kondo) reluctantly helps. It’s like suddenly finding yourself watching a completely different movie, although the connection to the main story does become apparent in the end. Otherwise, the film holds no major surprises, but the climactic tragedy is well-staged and it’s an effective cautionary tale about the dangers of pursuing revenge. It’s also worth viewing to see the face-off between Osaka and Kyoto personified by two of Japan’s top female stars.

Kawaguchi’s novel had the same title and was published the same year the film was released. It was based on the real-life rivalry between Rumiko Kawabe (1917-1989), proprietress of a bar called Espoir, and Hide Ueha, also known as Osome (1923-2012), who owned a bar of the same name financed by a politician. Matsutaro Kawaguchi was a regular customer at Osome. However, the feud between Kawabe (the model for Mari) and Okiku (the model for Osome) did not end in tragedy and it was even said they eventually became friends. Ueha appeared as herself in Yuzo Kawashima’s The Balloon (1956).

August 11, 2022

House of Wooden Blocks / 積木の箱 / Tsumiki no hako (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #32

Yoshiro Uchida and Ayako Wakao

Yoshiro Uchida and Ayako WakaoIn the 18th of her 20 films for director Yasuzo Masumura, Ayako Wakao plays a supporting character for the first time in their collaboration since the 1961 picture A Lustful Man. Even for a supporting role, the character she portrays in House of Wooden Blocks is not very interesting and certainly presents no challenge to her acting skills, so one wonders whether she would have agreed to the part had the choice been hers. The Japanese film studios at the time worked their stars very hard and would generally sooner put a star into a minor role than have them not working, so (unlike in Hollywood) it was not unusual to see them in around 10 films a year flitting between leads, supports and the odd cameo. It was also very difficult for stars to say no if they were under contract, as can be seen from the case of one of Daiei Studios’ other big female stars, Fujiko Yamamoto, whose film career came to an abrupt end in 1963 when she rebelled. Of course, it’s possible that Wakao may have felt some loyalty towards Masumura, but he was later to describe her as a ‘cold and calculating woman’ (whether or not this assessment is fair, I have no idea).

Kayo Matsuo and Yoshiro Uchida

Kayo Matsuo and Yoshiro Uchida

The main character in House of Wooden Blocks is Ichiro (Yoshiro Uchida), a boy of around 14 who is shocked one day to see his elder sister Namie (Kayo Matsuo) rolling around naked on the bed with his father, Goichi (Asao Uchida). He subsequently discovers that Namie is not actually his sister, but was adopted by his father as a child and later became his mistress. Now wanting to avoid his own family, Ichiro finds himself drawn to Hisayo (Ayako Wakao), a single mother who runs a local shop, and he becomes like an older brother to her young son. Meanwhile, Ichiro’s easygoing teacher, Sugiura (Ken Ogata), is also attracted to Hisayo, sparking feelings of jealousy in his pupil. Sugiura has noticed a change in Ichiro, who has become increasingly moody since realising the true nature of the relationship between his father and Namie. However, Sugiura’s efforts to help are rebuffed by Ichiro, who begins to wonder why Hisayo always avoids his father…

Ayako Wakao, Yoshiro Uchida and Ken Ogata

Ayako Wakao, Yoshiro Uchida and Ken Ogata

A more literal translation of the Japanese title would be ‘Box of Wooden Building Blocks’, but it seems to be a metaphor akin to the English ‘House of Cards’ in the sense that Goichi has built his family on shaky foundations and it won’t take much to send it all crashing down, which indeed proves to be the case.

Dealing with a young man’s simultaneous disillusionment and sexual awakening, Masumura apparently described this work as ‘a boy’s Vita Sexualis’, this being the title of a classic 1909 novel by the Japanese author Ogai Mori, best-known for the story on which Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff was based. However, this film was adapted by Masumura and Ichiro Ikeda from a just-published novel of the same name by Ayako Miura, who also supplied the source material for Satsuo Yamamoto’s Freezing Point (1966) starring Ayako Wakao. Masumura frequently adapted new novels and without a translation it’s hard to know how faithfully he did so, but I expect that much of the misanthropic vision to be found here and in other Masumura adaptations like Hanrancomes from him as it’s such a common thread in his work.

House of Wooden Blocksfeatures a restrained classical-style score by Tadashi Yamauchi, who had composed the music for a number of Masumura's other pictures, while the photography by another regular collaborator, Setsuo Kobayashi, looks a bit more rushed than in their previous work – perhaps a result of Daiei’s dwindling finances. The cast is also less distinguished than usual. A young and surprisingly skinny Ken Ogata tries hard as the too-good-to-be-true teacher, but it’s not much of a part. At the other end of the scale, shameless scene-stealer Kayo Matsuo certainly gives value for money as bitchy nympho Namie, but the characters here are simply too one-dimensional for the film to really hit home.

August 6, 2022

My Way /わが道/ Waga michi (1974)

Obscure Japanese Film #31

Nobuko Otowa

Nobuko Otowa

Taking place between 1966-1971, this is a work of social realism based on a true story and starring director Kaneto Shindo’s usual leading actress (also mistress and later wife), Nobuko Otowa. She plays Mino Kawamura, who lives in a neglected rural community badly in need of ‘levelling up’ where she runs a noodle shop with her husband, Yoshizo (played by Shindo’s other main regular, Taiji Tonoyama). The couple are in their 60s and struggling to get by as they have hardly any customers and both have health issues. In desperation, Yoshizo takes a trip in the hope of finding some temporary work as a labourer, but Mino becomes worried when his bag is found abandoned and sent back to her. She visits the police and reports him missing, but is repeatedly given the brush-off and spends the next nine months trying to find answers until she sees his photo in a collection of pictures of unidentified corpses at the police station. She then discovers that the corpse has been given to a medical university to dissect. There is a terrible moment when she insists on viewing the dissected body to ensure it really is her husband inside the cheap wooden box at the university. To make matters worse, Mino learns that, despite the presence of receipts in the dead man’s wallet which would have made it fairly easy to identify the body, no real effort had been made to do so. She refuses to let the matter lie and campaigns to expose the negligence of the system that has failed her so miserably.

Two great actors: Nobuko Otowa and Taiji Tonoyama

Two great actors: Nobuko Otowa and Taiji TonoyamaShot in academy ratio, My Way is not a very cinematic film, but it’s well-made and acted as one would expect from this filmmaker, while Hikaru Hayashi’s percussive music score helps to create a feeling of suspense. The problem is that, once we learn the fate of Yoshizo about an hour in, the narrative loses much of its interest and most of the second half is taken up by an interminable court case in which sundry sweaty policemen and doctors try to worm their way out of responsibility. This is simply too repetitive, predictable and over-extended.

Shindo clearly wanted to bring attention to the plight of those living in failing communities, and there are a couple of subplots involving women who resort to prostitution after their husbands have fled. These hardly help to lighten the tone, which is pretty grim on the whole despite the presence of various characters who rally round Mino and give her their support. One has to admire the incredibly prolific Shindo for tackling such difficult, uncommercial subjects and somehow getting them made, but in this case the second half is too flawed for the film to be counted a success.