M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 10

September 3, 2024

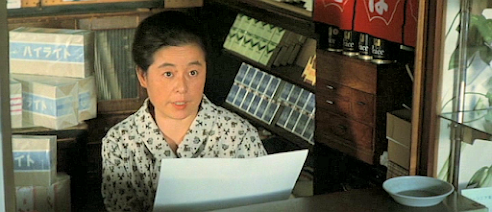

The Beloved Image/ 顔 / Kao (‘Face’, 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #129

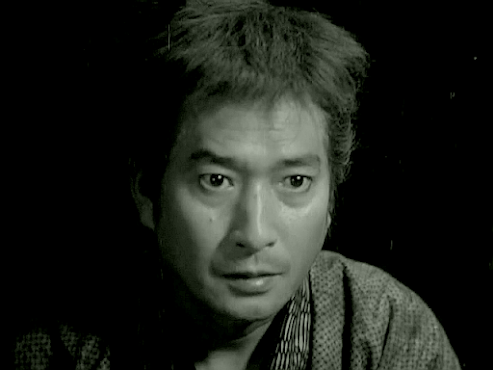

Machiko Kyo and Ryo Ikebe

Machiko Kyo and Ryo IkebeThis Daiei picture opens with young executive Ko (Ryo Ikebe) beingseen off at Haneda airport by his family and colleagues as he leaves Tokyo to spendtwo years working in America. He looks around anxiously to check that a youngwoman, Eriko (Machiko Kyo), is among the crowd. Relieved to find that she is,he bids her an awkward goodbye...

We then flashback to a couple of months previously as Ko arriveshome after work one day to find himself greeted by a stranger, who turns out tobe Eriko. The two have not seen each other since childhood, but Eriko has comeup from Kyoto to help look after her aunt, who is also Ko’s step-mother, Orie(Hisako Takihana), whom his father married after Ko’s natural mother had diedgiving birth to him. Now Orie is ill, and Ko’s father, highly respectedreligious scholar Kiyosu (Eijiro Yanagi), is not much help looking after her,so Eriko is a godsend. Ko and Eriko are mutually attracted to each other andsoon become close, but neither does anything about it as he will soon have toleave for America. However, before he goes, Ko asks Eriko to stay at the houseuntil he gets back, ostensibly to look after Orie.

No sooner has Ko departed than Orie takes a turn for the worse andpasses away. A couple of months later, Eriko accompanies Kiyosu on an overnightgolfing trip, sharing a room with him (it’s unclear why she has agreed tothis). Kiyosu forces himself on her, and the next day asks her to marry him.She accepts, perhaps because his status is such that she sees no way to refuse,or perhaps because she’s old-fashioned enough to think that it’s the onlycorrect thing to do. Anyway, she resigns herself to the idea, they marry, andshe gradually gets used to her new position even if she never feels entirelyhappy about it.

Two years pass, and Ko returns to Japan. The woman he hoped tomarry is now his new step-mother, so things are awkward between them and Kowants to move out of the family home and get his own apartment. Eriko decidesthat Ko needs a woman of his own as well, so she tries to fix him up with afriend of hers from Kyoto, widowed fashion designer Setsuko (Yasuko Nakada),but she finds that she can’t quite forget her own feelings for her lost love.

Based on a novel of the same title by Fumio Niwa* (here adapted byTeinosuke Kinugasa), this melancholy love story for grown-ups is beautifullyrealised in all departments, and I’m surprised it’s not better known. As adirector, former actor Koji Shima has a reputation as something of a hack whowould make any old thing, but here he shows such impressive skill and tastethat it’s difficult to believe he’s the same man responsible for the ridiculousstarfish-people sci-fi flick Warning fromSpace (1956). Here, he’s ably abetted by veteran cinematographer JojiOhara, whose compositions, lighting and camera movements are all frequentlyimpressive. There are some nicely symbolic shots, too, such as the one of themoth trapped inside a light when Eriko is raped, while excellent use is made ofthe weather throughout – on several occasions, interior scenes are played outagainst a backdrop of snowfall or a storm raging outside.

Regarding the music,there was something of a trend in Japanese cinema at the time for Spanishguitar, which can sometimes feel jarring and intrusive. In the hands ofcomposer Seitaro Omori here, however, it’s subtle and highly effective, addinga great deal to the emotional impact of the film without ever feelingmanipulative.

In the leading role, Machiko Kyo’s character changes a great dealin the course of the film, but she’s never less than entirely believable. Thesame can be said for Ryo Ikebe, an actor I’ve previously described as ‘wooden’ –and who could certainly never be accused of overacting – but who impressed mehere. This is a story largely about what is going on in the minds of Ko andEriko, and both actors prove highly adept at communicating this with a mereglance or slight change of expression even if the film occasionally resorts tovoiceover from both characters.

There’s also a brief appearance by Kyoko Enami in one of her firstfilm roles as Eriko’s rude niece, but it’s Yasuko Nakada as the seductive youngwidow who proves to be the major scene-stealer. She’s so good, in fact, that I’msurprised she failed to become a bigger star, especially as she was the mistressof Daiei president Masaichi Nagata; as it was, she broke up with him in 1964and retired from acting, but is still alive at the time of writing.

This is a superb film - rarely have I come across one so obscure of such high quality.

*Fumio Niwa (male, 1904-2005) also wrote the novels on which Women of Tokyo (1939), Naruse’s The Angry Street and Battle of Roses (both 1950) and KinuyoTanaka’s Love Letter (1953) werebased. The only Niwa published in English translation appears to be his novelThe Buddha Tree.

August 29, 2024

The Time of Reckoning / 不信のとき / Fushin no toki (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #128

Jiro Tamiya and Ayako Wakao

Jiro Tamiya and Ayako WakaoAsai (Jiro Tamiya) isan artist who designs advertising posters for a printing company owned byKoyonagi (Masao Mishima). As a loyal subordinate, Asai sometimes accompanieshis boss on his frequent excursions to the red light district. On one suchoccasion, Koyonagi becomes smitten with a naïve young newcomer, Mayumi (MarikoKaga), and decides not only to make her his mistress but to persuade her to havehis baby. Unfortunately, Mayumi turns out to be not only stupid and vulgar butstubborn and wilful to boot. Meanwhile, Asai becomes involved with bar hostessMachiko (Ayako Wakao), who knows that he is married but wants to have his babyand promises not to be a homewrecker. Asai’s wife is Michiko (Mariko Okada), acalligraphy teacher who appears unable to have children herself. Asai begins tofind it increasingly complicated to continue satisfying the diverging demandsof his job, his wife and his mistress…

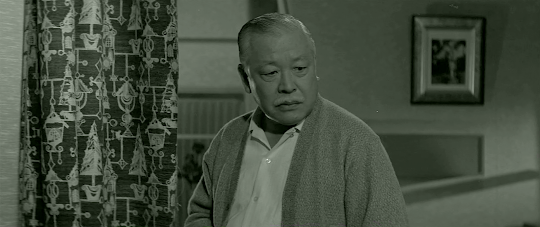

Mariko Okada

Mariko OkadaThe director of thisfilm, Tadashi Imai, was one of Japan’s most critically-acclaimed filmdirectors. However, after making Revengein 1964, his opportunities to helm feature films dried up for a while as theindustry as a whole was suffering an economic downturn, mainly due to so manypeople having recently bought TV sets, initially to watch the 1964 TokyoOlympics. As a result, Imai spent a couple of years making television dramasbefore returning to film work by directing the Ayako Wakao vehicle When the Sugar Candy Breaks (Satogashi ga kowareru toki, 1967) for Daiei. Wakao herselfhad recently had a success with The Wifeof Seishu Hanaoka (1967), based – like TheTime of Reckoning – on a novel by Sawako Ariyoshi, while her co-star inthis picture, Mariko Okada, had previously scored a hit with another film basedon an Ariyoshi novel, The Scent ofIncense (1964) and also been successfully teamed (or pitted against) Wakaoin Two Wives (1967). The Time of Reckoning, then, exists notas a project initiated by Imai, but as a vehicle for Daiei’s stars, Wakao andOkada, as well as Jiro Tamiya and Mariko Kaga. Personally, I detected littletrace of the earlier Imai in this film, which he seems to have approachedpurely as a job of work – it looks in every respect like a typical Daiei dramawhich could have been made by any one of their stable of directors.

This is the film whichgot Jiro Tamiya not only fired by Daiei, but blacklisted by the film industrywhen he had the temerity to complain about his billing below the three femalestars despite the fact that he was clearly playing the lead role. Thisover-the-top reaction by the studio seems almost feudalistic, and I doubt theydid themselves any favours as they lost not only a talented actor, but apopular film star. Tamiya’s character in this film is actually less of ascheming shit than those he often played – indeed, it’s hard not to feel somesympathy for him here despite the fact that he’s no saint.

Mariko Okada

Mariko OkadaFor her part, Mariko Okada isexcellent as usual, but makes slightly less of an impact than the other twofemale stars simply because her role gives her fewer opportunities.

Masao Mishima and Mariko Kaga

Masao Mishima and Mariko KagaThe other Mariko, Mariko Kaga, is pretty funny playing abrainless bimbo who nevertheless has a mind of her own (an oxymoron with theemphasis on ‘moron’?), but it’s Wakao who really shines here. Although hercharacter is for the most part quite placid, there are a couple of scenes in whichshe becomes emotional where you can see that Wakao is not merely ‘acting’,she’s really feeling it, as you can tell by the fact that you can even see herface visibly colouring at one point.

Perhaps that’s the main reason why she wonthe 1969 Kinema Jumpo Award for Best Actress for this film, House of Wooden Blocks and One Day at Summer’s End. I should alsomention that there’s a nice cameo from the Womanin the Dunes herself, Kyoko Kishida.

Kyoko Kishida

Kyoko KishidaWith an easy listeningjazz muzak score and an absence of any major tragedies, the tone of the filmleans more towards comedy than drama, although it’s seldom laugh-out-loudfunny. Instead, it opts for a similargentle irony to that of the recently-reviewed Furin, another film in which the women get the better of a man whothinks he’s got his two-timing arranged perfectly. Things get prettycomplicated and confusing towards the end and then the film finishes with anodd little non-ending (that I actually rather liked). It’s quite an enjoyable journey, but this is one filmthat will be best appreciated by fans of the stars rather than the director.

Mariko Kaga

Mariko KagaBonus trivia: Therehave been four TV versions, including a 1968 one with Keiju Kobayashi in theTamiya role and a 1984 one with Mariko Kaga switching roles to play Michiko.There was also a 1969 stage version starring Keiju Kobayashi in which MarikoOkada switched roles to play Machiko.

Note on the title: TheJapanese title translates more accurately as ‘Time of Distrust.’

Thanks to A.K.

August 25, 2024

A Town Not on the Map / 地図のない町 / Chizu no mai machi (aka ‘The Jungle Block’, 1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #127

Yoko Minamida

Yoko MinamidaShinsuke (Ryoji Hayama) is a young doctor who has had to resignfrom his post at a hospital after failing to save a patient. Returning to theshanty town where he grew up, he begins assisting the local doctor, Kasama(Jukichi Uno), who is greatly respected by the poor community he serves.

Unfortunately, the local yakuza boss, Azusa (Osamu Takizawa), has managed toobtain a contract to clear the shanty town and replace it with modern apartmentblocks. Meanwhile, Shinsuke’s sister Sakiko (Kazuko Yoshiyuki) is out walkingone night with her fiancé Kajiwara (Yasukiyo Umeno) when they are attacked by agang of yakuza and she is gang-raped. Shinsuke is appalled to find that, notonly is Kajiwara too spineless to go to the police, but he no longer wants tomarry Sakiko. If that wasn’t bad enough, he then learns that not only has his childhoodsweetheart Kayoko (Yoko Minamida) become a prostitute, but she has accepted anoffer to become Azusa’s mistress instead in order to pay off a debt owed by herfather (Jun Hamamura). Shinsuke decides to take matters into his own hands, butwhat can he do against such a powerful mob?

There’s a lot going on in this Nikkatsupicture, which starts out almost like one of Satsuo Yamamoto’s leftist dramas inwhich an oppressed community band together to take on their corrupt oppressors,but morphs into a Seicho Matsumoto-style murder mystery at the end. Based on a storyby Kaoru Funayama,* it was adapted by director Ko Nakahira and regular Kurosawacollaborator Shinobu Hashimoto. In the film, the story unfolds in a series ofconsecutive flashbacks (probably Hashimoto’s idea). This is an unusualapproach, but one that works well in this instance, with the tension buildingnicely as events reach their climax. When they do, there is perhaps a twist toomany, with the result that things become a little absurd – almost comic, infact (something I doubt was intended).

A Town Not on the Map benefits froma strong all-round cast. In the lead, Nikkatsu contract star Ryoji Hayama makesfor a sympathetic hero despite being better known for playing bad guys, whilethe underrated Yoko Minamida is equally good as the troubled cat-loving heroine,Osamu Takizawa makes a suitably loathsome villain, Jukichi Uno exudes integrityas only he could, Shobun Inoue is convincingly tough as a scar-faced yakuza, andJun Hamamura manages to look even more like death warmed up than usual.

The scoreby the great avant-garde composer Toshiro Mayuzumi is surprisingly conventionalfor him, but nonetheless highly effective. Director Ko Nakahira brings hiscustomary flair to the proceedings, with impressive staging and camerawork (byhis regular collaborator Yoshihiro Yamazaki) which is seldom pedestrian andoften memorably stylish.

Excellent subtitles by Stuart JWalton can be found here: https://www.opensubtitles.org/en/subtitles/9880312/the-jungle-block-en

*The original story, ‘Satsui nokage’ / 殺意の影 (‘Shadows of Murder’),appeared in Funayama’s 1957 collection Akutoku /悪徳 (Vice).

August 16, 2024

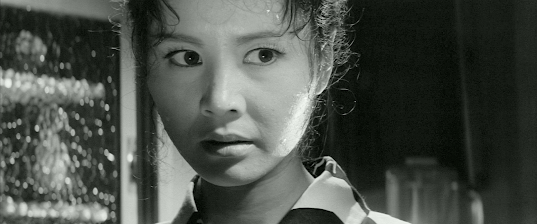

Furin / 不倫 (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #126

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoSaburi (Keizo Kawasaki) is a writer who has just won the Newcomer of the Year Award for his book ‘Sexual Aesthetics’. Despising marriage and thinking monogamy unnatural, he has ongoing sexual relationships with two women and has arranged it so that they visit his apartment on different days. The two women are the traditionally-minded Seiko (Ayako Wakao), who would like to get married but is too deferential to insist on it, and Maki (Kyoko Enami), a more modern type who usually wears Western clothes and is considering getting married to an American. The two women soon become aware of each other’s existence; when they finally meet, Saburi is disconcerted to see them getting on like a house on fire instead of fighting over him as his ego would prefer…

Kyoko Enami

Kyoko EnamiThis sex comedy eschews obvious gags and opts instead for irony – the more Saburo gets embroiled in this ménage à trois, the more of a conservative hypocrite he’s revealed to be. For all his preaching of emancipation, he still feels the need to lie and is no more immune to feelings of guilt and jealousy than anyone else. At one point, he begins to suspect that Seiko and Maki are having a lesbian affair – an idea he finds quite shocking.

Furin was based on a just-published novel of the same name by the prolific Koichiro Uno (just turned 90 at the time of writing). It’s a well-made and well-acted movie, especially by the two women, with Kyoko ‘Woman Gambler’ Enami making a strong contrast to Wakao’s more demure, but also more manipulative, character. The classical-style soundtrack and crisp black and white photography also lend considerable class, while the direction by forgotten veteran Shigeo Tanaka (see also Mikkokusha) is hard to find fault with.

The one slight bone of contention I have with this film is that Saburi’s life bears no resemblance to that of anyone I’ve ever known (though perhaps I don’t move in the right circles). He seems to do very little work, yet has no money worries whatever. It’s hard to understand why Seiko and Maki are interested in him as, not only is he rather nerdy and plain-looking, he has no particularly positive personality traits to make up for it. And Seiko does all his cooking for him, too – this is one dweeb who’s really got it made!

Keizo Kawasaki

Keizo Kawasaki

The title is sometimes translated as ‘Adultery’ in English, although it’s a poor fit as the protagonists are unmarried. Furin can also mean ‘impropriety’ or ‘immorality’, but these sound too judgemental given the context. For these reasons, it’s understandable that, when Daiei screened it in English at their then recently-opened New Kokusai Theatre in Honolulu, it was retitled ‘Strange Triangle’.

Thanks to AK.

August 8, 2024

Bonds of Love / 愛のきずな / Ai no kizuna (1969)

Obscure Japanese Film #125

Suzuki (Makoto Fujita) isa low-level manager at a travel agency who drives a modest car and isdissatisfied with his life. One night, driving home in heavy rain, he notices Yukiko(Mari Sono), an attractive young woman taking shelter by the side of the road,and manages to persuade her to accept a lift. He takes her home and she giveshim her card with the name of the restaurant where she works. The two beginseeing each other, but things become complicated when it emerges that they eachhave a secret…

To reveal any more ofthe plot would spoil this movie – it’s based on a Seicho Matsumoto story, so thetwists are kind of the point. However, I feel I should comment on one dramaticevent so far as to say that a crime committed by one of the protagonists mayseem random and unmotivated to non-Japanese viewers, but I believe that themotivation is the character’s desire to silence the victim by any meansnecessary in order not to lose face (which would also result in a loss ofstatus and position). Incidentally, the original story was entitled‘Tazutazushi’ and published in 1963; this remains the sole film version,although it has been remade for TV three times since.

Director TakashiTsuboshima seems to have recognised the absurd aspects of the story andapproached it as a black comedy, albeit one that’s played fairly straight forthe most part. One notable exception is a slapstick sequence when a distractedSuzuki pours milk and sugar into an ashtray instead of his coffee cup. Thechoice of Makoto Fujita for the leading role works in the film’s favour – hedoesn’t look in the least like a film star, and wasn’t one, though he was apopular TV star (often in comic parts) and also gave a notable performance in aleading role in Masaki Kobayashi’s Hymn to a Tired Man.

Fujita’s co-star here, Mari Sono, was a famous pop singer whopassed away very recently at the age of 80. Considering she was not a trainedactress, she does pretty well here. There are also strong supportingperformances by Makoto Sato and Chisako Hara as well as a cameo by NorikoSengoku.

Bonds of Love is a very engaging and well-made variation on theMatsumoto crime formula; Tsuboshima’s slightly tongue-in-cheek approach to thematerial may be unexpected, but feels exactly right given the implausibility ofthe plot. Tsuboshima (1928-2007) was a minor director, many of whose films werevehicles for a popular group of comedians/musicians known as the Crazy Cats; Bonds of Love seems to have been ananomaly in his filmography. It was a co-production between Toho and WatanabeProductions, a company belonging to Shin Watanabe (1927-87), a former jazzbassist who started the company as a talent agency in the 1950s beforeexpanding into film production in 1962, subsequently producing at least 48films, virtually all of which have fallen into obscurity.July 30, 2024

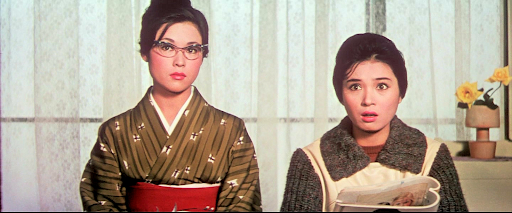

Konki / 婚期 / 'Marriageable Age' (1961)

Obscure Japanese Film #124

Takuo (Eiji Funakoshi) runs an inn (a family business he has inherited), and lives not just with his wife, Shizuka (Machiko Kyo), but with his two sisters – Namiko (Ayako Wakao) and Hatoko (Hitomi Nozoe), who are financially dependent on him and on the lookout for husbands. Namiko, 29, teaches calligraphy to children and is in danger of becoming an old maid (although it was unclear to me why). Hatoko, 24, is trying to become an actress but only getting tiny parts. The two sisters get on well, spending much of their time together, and are united in their dissatisfaction with Shizuka, perhaps because she does not run a perfect house and relies too heavily on the elderly maid (Tanie Kitabayashi).

One day, Shizuka receives an anonymous letter telling her that her husband has a mistress with whom he has had a child, but she seems only a little perturbed by this. In this dysfunctional family, the only person who seems to have their shit together is Takuo’s sister, Saeko (Mieko Takamine), an emancipated divorcee who lives apart from the rest, works in the fashion industry and sees through her womanising brother…

Director Kozaburo Yoshimura was better-known for his more serious literary adaptations, but on this occasion he successfully turned his hand to a domestic comedy from an original screenplay by frequent Tadashi Imai / Mikio Naruse collaborator Yoko Mizuki (1910-2003). Mizuki actually won the 1962 Best Screenplay Award for this and Tadashi Imai’s The Harbour Lights (1961). In the case of Konki, the screenplay is a dialogue-heavy one which allows the mostly female ensemble star cast to have a field day.

Despite watching twice with decent if imperfect subtitles, I still felt that there was a great deal I didn’t understand, and I suspect that you have to be Japanese to really get this one. The subtitles sometimes struggled to keep up with the often rapid-fire dialogue, with the result that it was not always clear who was saying what to whom. I also suspect that the ending had a point to it which sailed right over my head. Nevertheless, there’s a lot to enjoy here, with Ayako Wakao and Hitomi Nozoe making a great comic double act. The real star of this movie, though, is Tanie Kitabayashi, an actress who specialised in granny roles. She was around 50 when she made this, but was playing at least 20 years older. She’s hilarious here as the put-upon help, and the splendidly reluctant intonation she puts into a simple ‘hai’ (‘yes’) when instructed to do something is priceless.

One notable aspect of the film is the sheer amount of business the actors find to do while delivering their dialogue. Whether it’s Wakao marking her pupils’ calligraphy homework, Nozoe cutting her toenails, Takamine removing a face pack or Kitabayashi grating dried bonito, Konki is a masterclass in the use of props, and the skilfully co-ordinated interaction of the various cast members shows their considerable acting chops. While the film may be baffling at times for non-Japanese viewers, anyone who loves these actors and Daiei films of this era (as I do) should certainly seek it out.

Thanks to Anonymous.

July 26, 2024

The Pass – Last Days of the Samurai / 峠 最後のサムライ / Tōge saigo no samurai (2020)

Obscure Japanese Film #123

Koji Yakusho

Koji YakushoThis Shochikuproduction stars Koji Yakusho, well-known for his leading roles ininternational hits such as Shall WeDance? (1996), The Eel (1997)and, most recently, Perfect Days (2023).Here, he plays Tsugunosuke Kawai (1827-68), a senior samurai retainer preparingfor civil war while simultaneously doing everything he can to prevent it, eventhough it means being called a coward by many of his peers as a result. Thestory is set in the years 1867-68 when the influence of America and Europe isbeginning to make itself felt in Japan, and Kawai has been inspired in hisneutral stance by the example of Switzerland. However, the film certainly hasan ambivalent attitude towards the West as the opening narration suggests thateverything would have been fine in Japan if only the Western world had leftthem alone. Indeed, Kawai himself is a rather contradictory character – despitesticking his neck out in the hopes of maintaining peace, he ends up gleefullymowing down his opponents with a Gatling gun! (Incidentally, although such aweapon may seem out of place in a samurai movie, it is a historical fact thatKawai purchased a Gatling gun, though whether he used it himself in battle Ican’t say.)

ThePassis based on a 1968 novel by Ryotaro Shiba (1923-96), whose work also providedthe basis for films such as Castle ofOwls (1963), Assassination(1964), Hitokiri (1969) and Gohatto (1999). The film appears to be afaithful adaptation as far as one can tell without reading the book, which isyet to be translated into English (though some of Shiba’s work has been).

The man responsible forthe adaptation is writer-director Takashi Koizumi, a former assistant directorto Akira Kurosawa who had made After theRain (1999) from Kurosawa’s script after his mentor’s death. Among the castare long-in-the-tooth Kurosawa veterans Tatsuya Nakadai (b.1932), Kyoko Kagawa(b.1931) and Hisashi Igawa (b.1936), though they are given nothing verychallenging to do and their parts are cameos of the “wheel ‘em out for oldtimes’ sake” variety. Still, we have to be thankful for any appearance by thesegreats of Japanese cinema these days.

The historical accuracyof the piece seems generally solid with the exception of the casting – KojiYakusho, then 64, is playing a 40-year-old, while his former acting teacher TatsuyaNakadai, then 87, plays Kawai’s boss, samurai lord Tadanori Makino (1844-75),who died at the age of 30! Perhaps wisely, no attempt has been made to make Nakadailook half a century younger – the filmmakers’ presumably thought that only afew history nerds would notice the discrepancy.

ThePassis often very impressive visually and looks like it must have been given agenerous budget, with the large-scale battle scenes being especially well done.On the other hand, its quieter moments are sometimes a bit too fussy and picture-postcardyfor their own good, with some scenes feeling pretty lifeless as a result. Themusic is also a mixed bag, varying from sentimental light classic piano to moredramatic and effective orchestration for the battle scenes. However, for me it ismainly in the script department that this film is lacking as, not only does itpresent us with a nostalgic, rose-tinted view of the past, but we have tosuffer dialogue like, “Your samurai spirit will inspire countless others. Youare our ideal. You shall live on in history!” For me at least, the film isideologically dubious in the way it seems to lament the passing of feudalism.While it may be true that, under the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan enjoyed 260-oddyears of peace and stability during the Edo period (1603-1868), this was only achievedby enforcing a policy of isolationism and a rigid social hierarchy. Such a situationmay have been comfortable for the aristocracy, but was doubtless a lot less pleasantif you were one of the oppressed, and the film never shows us this side.

Takako Matsu as Kawai's wife, Suga

Takako Matsu as Kawai's wife, Suga

Despite these quibbles,it’s a shame that The Pass has yet toreceive a proper release overseas. While uneven, its best bits make it worthseeing and it features an engaging performance by Yakusho in the lead. Kawaiwas also certainly an interesting figure worthy of a movie (I believe this wasthe first feature film in which he was the main character, though there hadbeen TV dramas before).

The film’s release wasdelayed until 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

For a more detailedsynopsis, see Hayley Scanlon’s review here.July 16, 2024

The Horse Boy / 暴れん坊街道 / Abarendo kaido (1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #122

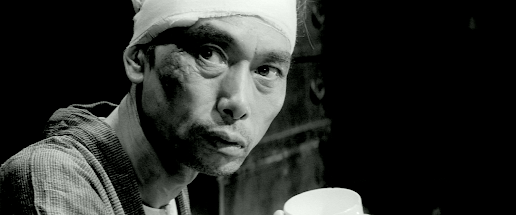

Shuji Sano

Shuji Sano

Isuzu Yamada

Isuzu YamadaYosaku (Shuji Sano) is a low-ranking samurai employed at Yurugi Castle in Tanba Province. He has a secret affair with Shigeno (Isuzu Yamada), the daughter of senior retainer Inaba Kotayu (Kenji Usuda). When she becomes pregnant, he is banished from the castle, while she gives birth to a baby boy, but is not allowed to keep him and has to watch helplessly as he is taken away. Shigeno is then assigned to act as wet nurse and carer for another infant – a new-born princess.

Motoharu Ueki

Motoharu UekiTen years pass, and Yosaku has become a wandering ronin. While travelling, he hires a horse from Sankichi (Motoharu Ueki), a precocious urchin who gambles and smokes a pipe. Looking for somewhere to rest up, Yosaku is taken to an inn next to the little shack in which Sankichi lives. Yosaku becomes friendly with the boy as well as with Koman (Shinobu Chihara), a young woman who works at the inn.

Shinobu Chihara with Ueki an Sano

Shinobu Chihara with Ueki an Sano

When a procession from Yurugi Castle passes through, it gets delayed when the young princess has a tantrum and jumps out of her palanquin. Shigeno fails to persuade her to get back in so they can continue her journey, but the princess discovers Sankichi gambling by the side of the road and is drawn to him, with the result that Sankichi is asked to accompany the retinue to the castle. Shigeno is shocked to discover that Sankichi is in possession of the omamori (amulet) she had tied around her son’s neck when forced to let him be taken from her all those years before…

The screenplay was adapted by Yoshikata Yoda (best known for his many screenplays for Kenji Mizoguch) from a jurori* entitled The Night Song of Yosaku from Tamba (Tamba Yosaku machiyo no komurobushi) by Monzaemon Chikamatsu (1653-1725), the dramatist later portrayed by Chiezo Kataoka in Chikamatsu’s Love in Osaka (1959). That film was, of course, directed by Tomu Uchida, as was The Horse Boy.

With a new emphasis placed on the character of Sankichi, this Toei production seems to have been intended mainly as a vehicle for child actor Motoharu Ueki, who was the eldest son of Chiezo Kataoka, a legendary actor and great favourite of Tomu Uchida. Kataoka had been the star of Uchida’s first post-war film, Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955), and went on to appear in a further nine films for him, while Ueki had also appeared in that film as well as Uchida’s The Kuroda Incident (1956) and Rebellion from Below (1956) and would also be featured in The Eleventh Hour (1957).

Shigeno lives in a world of extremely refined manners in which etiquette dominates behaviour and rebellion is unthinkable, while the abandoned Sankichi has no manners at all and does what he likes. Uchida makes much of this contrast between the two very different worlds they inhabit. Unfortunately, my personal reaction was that Sankichi’s rude behaviour did not endear him to me at all, and for this reason I was never as moved as I felt I was probably supposed to be by this film, which I would definitely consider a minor work in Uchida’s filmography. I felt that Uchida saved his best bit of direction for a scene which occurs late in the film and takes place on a quiet road at night when a confrontation between Yosaku and the local moneylender (Eitaro Shindo) turns violent. Incidentally, Shindo is the stand-out among the supporting cast and could always be relied upon to play a man-you-love-to-hate effectively.

Sano confronts Eitaro Shindo

Sano confronts Eitaro ShindoIt’s worth noting that, while Chikamatsu’s original apparently had a happy ending, Uchida’s film does not, and perhaps this is because he preferred to make it clear that the unforgiving rules of Japan’s former feudal society had ruined a lot of lives.

Note on the title: The Japanese title translates as something like ‘Wild Child of the Road’.

*Wikipedia defines jurori as “a type of sung narrative with shamisen accompaniment, typically found in bunraku, a traditional Japanese puppet theatre”.

Watched without subtitles.

July 11, 2024

Song of the Horse / 馬の詩 / Uma no uta (1971)

Obscure Japanese Film #121

Toshiro Mifu-neigh?

Toshiro Mifu-neigh?

Akira Kurosawa’s onlywork for TV was this documentary co-producted by his own company and NipponTelevision. It’s unlike any of his feature films and should not be approached with high expectations.

Kurosawa had alwaysloved horses, which were of course an important element in many of his movies,perhaps most memorably in the post-battle sequence in Ran, where we see them dying in slow-motion to the strains of ToruTakemitsu’s haunting score. However, Songof the Horse is far lighter in tone, and therein lies the rub…

It would have beenpreferable to present this as the life of a single horse, but – as that wouldhave involved a shoot spread across a number of years – Kurosawa’s documentary instead follows the lifecycle of horses raised for racing. Following some introductoryfootage of a traditional festival at which horses are dressed up and paraded,we see a horse being born and later cavorting in a field on its first day outof the stable. The film goes on to show us how racehorses begin to be trainedat one year of age before running their first races at the age of two andcompeting in major events the following year. This is interspersed with footageof horses having their hooves trimmed, horses being groomed, horses being soldat auction, etc. Throughout the film, there is intermittent narration in theform of an informal conversation between an elderly-sounding man and a youngchild, both of whom are reacting to the images we see, most of which iscomprised of endless scenes of horses running in slow-motion. (The narration isby Noboru Mitani and Hiroyuki Kawase, who played, respectively, the homeless father and son inDodes’ka-den; I suspect that Mitani was given scripted material and Kawase reacted spontaneously, but this is speculation). There's also a music score by Kurosawa regular Masaru Sato which is decent if not great.

The documentaryconcludes by showing us a retired racehorse now living in luxury, and I couldnot help but wonder if this was really representative of how such horses weretreated in Japan at the time. Were none of them turned into dog food and glueonce their usefulness had expired? Kurosawa never addresses the issue of howthese animals are exploited, and for me that makes this film feel ratherdishonest. Instead, we are presented with a world in which horses only want todo their best and are thrilled when they win a race for their two-leggedmasters.

Kurosawa is myfavourite director, so it pains me to be so negative about this one, but in my opinion Song of the Horse is worth watching for Kurosawa completists and equestrian freaks only.

July 6, 2024

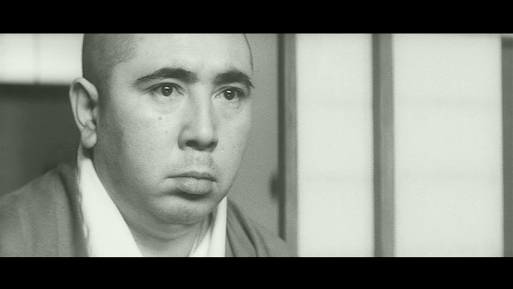

The Virgin Witness / 処女が見た / Shojo ga mita (1966)

Obscure Japanese Film #120

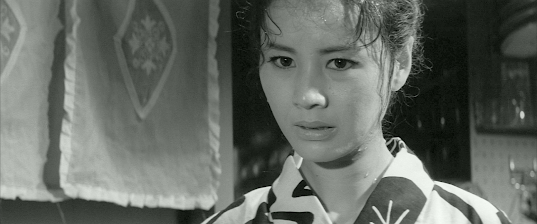

Michiyo Yasuda

Michiyo YasudaKazue (Michiyo Yasuda) is an 18-year-old orphan who has been adopted by her uncle and aunt, with whom she does not get along. Troubled and rebellious, she is prone to violent emotional outbursts which cause her to be expelled from school, leading her uncle to beg the local Buddhist head priest (Shozo Nanbu) to find a suitable temple to take her in.

Kazue is brought to a temple run by Chiei (Ayako Wakao), an attractive young nun who is initially strict and somewhat remote with Kazue, who soon learns that life there will mostly consist of chanting sutras, cleaning, and eating tasteless food. However, Kazue finds herself drawn to Chiei. In one unlikely scene, she manages to persuade Chiei to join her at the concert of a band she is friendly with (they play American-style surf rock in the style of The Astronauts).

Chiei is shocked to find that she enjoys it, and the two women become closer, but – just when it seems that Kazue might find some sort of stability at the temple – the head priest dies and is replaced by a younger man (Lone Wolf and Cub star Tomisaburo Wakayama).

Unfortunately, he seems to have gone to the Ganjiro Nakamura / Masao Mishima school of Buddhism* and exhibits rather too much enthusiasm for worldly pleasures, quickly developing an inappropriate interest in Chiei, who finds herself in an impossible position…

This Daiei production recycles elements of The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (filmed by Kon Ichikawa as Conflagration) and Ayako Wakao’s earlier film The Temple of Wild Geese, but in those stories the troubled youth was a male. Michiyo Yasuda (in her first film for Daiei after starting out in a couple of films for Nikkatsu) is excellent, going from flaming-eyed fury in one scene to moving vulnerability in another before switching to cool calculation towards the end. She does all of these well, and it’s arguably more her film than it is Wakao’s. Following the success of this picture, Yasuda was immediately reteamed with Wakao for the excellent Freezing Point (1966), then went on to play the female lead in Yasuzo Masumura’s remake of A Fool’s Love the following year.

Although Ayako Wakao’s performance is of her usual high standard, there is something of a disconnect between the way she plays her part and the words she has to say in a couple of the later scenes. In my opinion, the script is to blame for this as, despite the fact that Chiei is obviously supposed to be an intelligent woman, her actions are at times too foolish to be plausible. That’s a pity as this is otherwise a pretty good movie, well-made as one would expect from director Kenji Misumi.

*Ganjiro Nakamura and Masao Mishima played hypocritical priests in Conflagration (1958) and The Temple of Wild Geese (1962) respectively.

Chisako Hara

Chisako Hara