M.R. Dowsing's Blog, page 11

June 24, 2024

The Precipice / 氷壁 / Hyoheki (1958)

Obscure Japanese Film #119

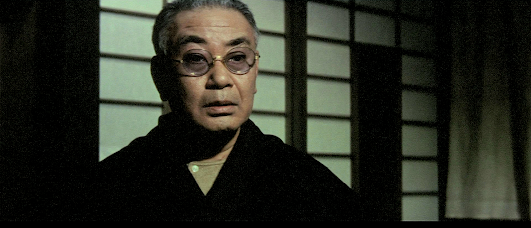

Kenji Sugawara

Kenji SugawaraWhen salaryman Uoza (KenjiSugawara) returns from a mountaineering trip and encounters his friend andformer climbing partner Kosaka (Keizo Kawasaki) in a restaurant, he’sastonished to find that Kosaka is there to meet a married woman, Minako (FujikoYamamoto).

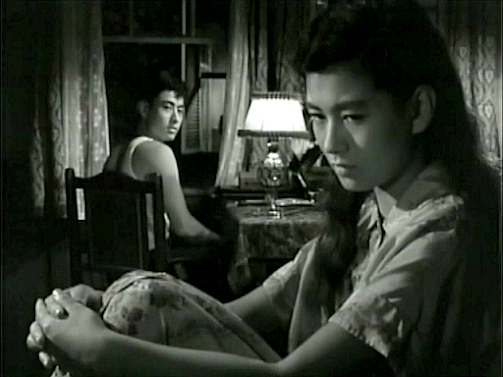

Keizo Kawasaki and Fujiko Yamamoto

Keizo Kawasaki and Fujiko Yamamoto

Feeling awkward, Uoza makes his excuses and leaves, but Minakocatches up with him outside and asks if she can speak to him. Uoza learns thatthe relationship between Kosaka and Minako has been going on for a whilealthough they’ve only slept together once. She regards the event as a moment ofmadness on her part and has been trying to break if off, but Kosaka has fallenhead over heels for her and won’t accept this, so Minako wants to enlist Uoza’shelp in order to make Kosaka see sense. Minako’s anxiety mayalso be partly due to the fact that her older husband, Yashiro (Ken Uehara withwhite hair), is a man not easily deceived.

Uoza decides to take Kosaka with himon his next trip to the mountains, where they attempt a difficult climb whichUoza hopes will take his friend’s mind off his emotional troubles. He alsotakes the opportunity to try and talk some sense into Kosaka, who finally seemsto be resigning himself to a life without Minako. However, when they continuethe last stage of their climb, Kosaka’s supposedly unbreakable nylon ropebreaks and Uoza can only watch in horror as his friend falls down themountainside…

Yasuzo Masumura’sfourth film as director covers similar territory to his better-known picture A Wife Confesses (1961). Kaneto Shindo’sscreenplay was based on a novel published the previous year by the prolificYasushi Inoue, who would go on to become one of Japan’s most respected authorsbut had yet to acquire that status. At the time, Inoue’s story was a topicalone as he had based it on a couple of recent mountain accidents involving a newtype of nylon rope.

In the lead, actorKenji Sugawara is a little on the stolid side, but was probably selected asmuch for his physical toughness – he was a 3rd dan in judo – as his actingability. The film’s location photography is impressive and it certainly appearsas if at least some of the climbing sequences were shot on location at MountHotaka in challenging conditions.

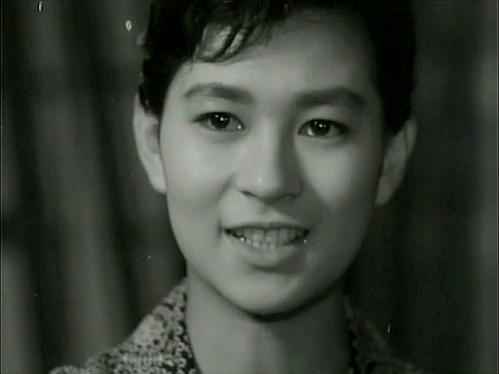

In the latter half ofthe film, Hitomi Nozoe has an important part as Kosaka’s sister. Any appearanceby Nozoe is welcome in my view as she was an underrated actor, and herbrilliant comic performance in Masumura’s Giantsand Toys made that movie (and as we can see here, there was nothing wrongwith her teeth!). Another actor who makes an impression is Kyu Sazanka, who usesevery trick in the book to steal all of his scenes as Uoza’s boss.

ThePrecipice was shot in Daiei’s briefly-adopted VistaVisionprocess, with an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, so it’s a little unusual in thatrespect as it was the 2.35:1 format that rapidly became standard in Japanaround this time, replacing the old academy ratio of 1.33:1. Masumura and hiscameraman Hiroshi Murai (who later shot Swordof Doom) use the VistaVision format to good effect here, pinning thecharacters down with clever blocking of scenes, with the camera closely followingtheir every movement, and managing to squeeze in two or even three of the maincharacters at once when appropriate.

The plot has itsflaws, with one unlikely coincidence feeling especially unnecessary, but it’s such a well-made film that it remains worth watching, and themoving music by Akira Ifukube is a major asset. Inoue's story hasproved a popular one in Japan and been remade for TV on a number of occasions.

Note on the title: TheJapanese title translates as ‘Ice Wall’.

June 17, 2024

A Dangerous Age / 続十代の性典 / Zoku judai no seiten (1953)

Obscure Japanese Film #118

Ayako Wakao

Ayako Wakao

The Japanese title ofthis film (which translates as ‘Teenage Sex Diary Sequel’) is somewhatmisleading as this is a separate story from Judai no seiten and, while it again features Yoko Minamida, Ayako Wakao and MikiOdagiri, they are playing new characters.

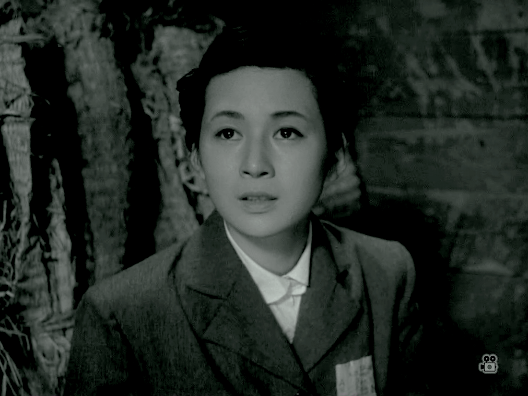

Yoko Minamida

Yoko MinamidaAkiko (Minamida) is an18-year-old high school student at a single-sex (possibly Catholic) school. Oneday, seeing Yoda (Ken Hasebe), a male student, drop a watch in the street, shepicks it up and runs after him to return it, but he jumps onto a train beforeshe can do so. She manages to find him at the station the next day, when hetreats her to coffee and cake before inviting her to see his flat. Akikonaively accepts, but flees the place after he makes a pass. As she leaves, Yodacalls after her, saying that she is welcome to visit anytime.

Jun Negami

Jun NegamiMeanwhile, Akiko’s bestfriend, Natsuko (Wakao), accepts an invitation from Toshio (Yosuke Irie) to aparty but is forced to stay home by her mother, who wants her to study maths athome with the new tutor she’s hired, a medical student named Masato (JunNegami). Feeling guilty at standing up Toshio, Akiko pays him a visit the nextday to apologise. However, when she failed to appear, he had ended up beingseduced by an older woman (Murasaki Fujima) and losing his virginity. Natsuko has no knowledge ofthis, so she’s shocked to find that the sweet, gentle boy she had known haschanged overnight and now thinks that he’s Dan Duryea. When Toshio tries toforce himself on her, she gives him a few slaps and a good telling off, anddecides not to see him again. Despite her annoyance, Natsuko takes the incidentin her stride, forgets about him and moves on.

Akiko, on the otherhand, proves less able to handle this kind of situation. Natsuko’s new tutor isactually Akiko’s cousin, whom she has feelings for, so she begins to feel jealousas she sees Masato taking an interest in his new pupil, even though thisjealousy proves groundless. Masato is actually so much in love with his cousinthat his thesis is on the viability of incestuous marriage. Nevertheless, Akiko’sfeelings of insecurity are compounded when she discovers that her widowedmother (Kuniko Miyake) has been having a clandestine relationship with a businessman, Ueda (NobuoNakamura). Believing herself unwanted, she remembers her open invitation toYoda’s apartment and foolishly goes there, where she is not only raped butimpregnated. When she misses her period, her bitchy classmate (Miki Odagiri)begins to suspect the truth and starts spreading rumours. Things come to a headwhen the pregnant Akiko finds herself cast as that icon of purity, Joan of Arc,in the school play…

Miki Odagiri

Miki Odagiri Ayako Wakao, Yoko Minamida and Michiko Saga

Ayako Wakao, Yoko Minamida and Michiko SagaThis is a slightimprovement on Judai no seiten asit’s not quite as risible despite some daft moments. Director Koji Shima hasbeen replaced by the younger Kozo Saeki (1912-72), who also made The Girl Who Tamed Beasts. At first, Ithought that the Christian propaganda featured in the first film had been scrappeduntil I noticed that Michiko Saga (in one of her first film appearances, here playinganother classmate of Akiko’s) was wearing a crucifix, and then Ayako Wakaoappeared playing a bishop in the school’s Joan of Arc play. I’m unsure how toaccount for the Christian theme, but perhaps screenwriter Katsuya Susaki orproducer Itsuo Doi (both of whom worked on all four films in this series) wereChristians, or perhaps it was normal during this period for reasonably wealthyJapanese families to send their daughters to Catholic schools. In any case,although we may laugh at certain aspects of these movies today, it’s notdifficult to see how they might have served a valuable function at the time inencouraging discussion of awkward subjects.

June 11, 2024

The Third Will / 女系家族 / Nyokei kazoku (1963)

Obscure Japanese Film #117

Ayako Wakao

Ayako WakaoThis Daiei production was an attempt to repeat the success of thecompany’s 1961 film, A Woman’s Medal,and reunites stars Machiko Kyo, Ayako Wakao and Jiro Tamiya in anotheradaptation of a Toyoko Yamasaki novel (which had just been published as amagazine serial when the film went into production). Like the earlier picture, The Third Will is also a very talkyaffair involving a variety of scheming characters, although it perhaps alsoowes something to Masaki Kobayashi’s TheInheritance (1962).

Yachiyo Otori, Machiko Kyo and Chieko Naniwa

Yachiyo Otori, Machiko Kyo and Chieko Naniwa

When Kazo Yajima (the president of a cotton wholesale company inOsaka) dies, his three daughters assume they will inherit everything betweenthem. The domineering eldest daughter, Fujishiro (Machiko Kyo), tries to takecontrol, but faces rebellion from her younger sisters, Chizu (YachiyoOtori) and Hinako (Miwa Tanako), and the squabbles begin. Fujishiro seeksadvice from her younger dance teacher (Jiro Tamiya), who subsequently seducesher, hoping he can marry Fujishiro for her money. Another family member, AuntieYoshiko (Chieko Naniwa), comes up with a plan to adopt Hinako, hoping that thiswill enable her to grab a slice of the pie for herself. Meanwhile, Uichi(Ganjiro Nakamura), the head clerk who has been appointed executor of the willand has a few schemes of his own going, reveals to their dismay that Kazo hadsecretly been keeping a mistress, Fumino (Ayako Wakao), a former geisha.Although no specific inheritance has been granted to her in the will – whichmentions only that she should be treated with generosity – the family conspireto ensure that Fumino is sent packing with nothing. However, this proves to betheir undoing, and the story concludes in a satisfying (if predictable) manner.

The Yajima family are an appalling bunch of arrogant, entitledsnobs, and your sympathy will be entirely with Fumino here. The acting by theprincipals is excellent (as one would expect from this cast), and there’s alsoa notable performance by Chieko Naniwa as the auntie who turns out to be thenastiest of a very nasty lot who treat their servants like dirt and neglect therental properties that their long-suffering tenants are unfortunate enough tolive in.

The film itself is very similar to A Woman’s Medal in many ways, despite being made by a differentdirector. Kozaburo Yoshimura directed the earlier film rather indifferently,and I suspect that he would not have been a huge fan of a non-literary writerlike Yamasaki and that A Woman’s Medalwas a project assigned to him by the studio (though this is speculation on mypart). This would explain the change of director here,* which in the case of The Third Will is Kenji Misumi, afilmmaker who would become known for his stylish Zatoichi and Lone Wolf andCub movies but at this stage was still regarded as a jobbingdirector. This is not the kind of film one associates with Misumi, but he seems to have been a little more engaged than Yoshimura and brings what style he can to thedialogue-heavy scenes. The way he uses the sound of cicadas screaming in theclimactic scene is particularly memorable.

The film’s scathing portrayal of the moneyed class and lapses intomelodrama have led some to interpret it as a satire, which is not unreasonable.However, if it is intended as satire, I doubt this came from Toyoko Yamasaki, asher formula seldom varied and consisted of straight social commentary intendedto expose the hypocrisy and corruption existing behind the scenes in varioushallowed institutions.

Given the soap-operatic nature of the plot, it’s understandablethat, despite being another success for Daiei, The Third Will has not been remade for the big screen; moreappropriately, it has spawned no fewer than eight TV versions in Japan.

*The cerebral haemorrhage that Yoshimura suffered in 1963 isprobably not the reason for the change as TheThird Will was released in March of that year and Yoshimura’s Bamboo Doll of Echizen (his final filmbefore his 3-year hiatus) was released in October.

Note on the title: The Japanese title translates as ‘Matrilineal Family’,a theme also covered by Toyoko Yamasaki’s earlier novel Bonchi, filmed by Daiei in 1960.

June 5, 2024

Sweet Secret / 甘い秘密 / Amai himitsu (1971)

Obscure Japanese Film #116

Tomomi Sato

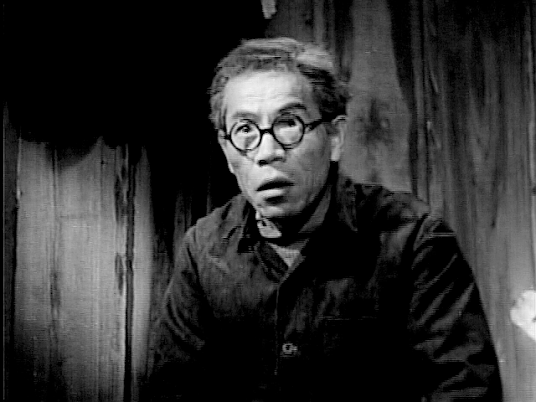

Tomomi Sato Eitaro Ozawa

Eitaro Ozawa

Yoko (Tomomi Sato) is ayoung woman living in Hokkaido who wants to be a writer. She persuades herhusband to take her to Tokyo in order to visit Inamura (Eitaro Ozawa), an olderwriter she admires whom she hopes may help her find a publisher for her debutnovel. Inamura is uncertain of her talent and non-committal, but makes a vaguepromise to read it properly when he has time. When pressed, he passes it on toa publisher friend, Isshiki (future director Juzo Itami), who happens to bepresent, and Yoko reluctantly returns to Hokkaido to await a response. However,within a couple of days she has left her husband and come to Tokyo permanentlyto pursue her literary ambitions.

Yoko begins an affairwith Isshiki, who arranges the publication of her novel. She then begins asecond affair with Yamaji (Toshiyuki Hosokawa), the young artist who designsthe cover for her book. Meanwhile, she is pursued by Akimoto (Hosei Komatsu), acousin from Hokkaido with whom she has also had an affair. After Inamura’s wife(Yatsuko Tan’ami) dies suddenly, she begins a May-December romance with him andmoves in with his family, much to the consternation of his daughter (EmiShindo) and the maid (Kotoe Hatsui), although his son (Sho Miyashita) welcomesher, thinking it will relieve his father’s loneliness. However, Inamuragradually begins to suspect that Yoko is continuing to see other men behind hisback, while she finds his possessiveness suffocating…

Although distributed byShochiku, this is (like the previously reviewed Wedding Day) an independent production by Kindai Eiga Kyokai, thecompany formed by director Kozaburo Yoshimura, screenwriter Kaneto Shindo andactor Taiji Tonoyama in 1950. Shindo’s screenplay is based on a series ofstories written by Shusei Tokuda (1872-1943) about his relationship with themuch younger writer Junko Yamada (1901-61), and it’s clear that Tokuda andJunko are the basis for the characters of Inamura and Yoko. In the film, theflighty and sometimes childish Yoko seems a highly unlikely writer, but it maybe that her portrayal is close to the reality of Junko Yamada. According toJapanese Wikipedia, although she published more than 10 books and dozens ofessays in magazines and newspapers, she was never taken seriously because of howshe had been portrayed in Tokuda’s stories, and is remembered mainly as thesubject of scandal rather than for her literary work. (Of course, it could bethe case that this lack of attention from the critics was unfair).

I was not entirelyconvinced by the casting of Tomomi Sato, who had previously played thestewardess in Goke, Body Snatcher fromHell (1968), surely one of the worst films I’ve ever seen. Her performance hereis by no means terrible, but it lacks the subtlety and depth that Ayako Wakaomight have brought to it. Sato had actually studied with the Haiyuza theatrecompany, which may have had something to do with her casting as the cast alsoincludes two founding members of Haiyuza, Chieko Higashiyama and, in a rareleading role, Eitaro Ozawa. As a man old enough to know better but unable tocontrol himself once his long-dormant passion has been revived, Ozawa isexcellent.

The music by Sei Ikenoflits back and forth between irritatingly repetitive bossa nova lounge muzakand some more effective brooding strings for the darker moments. Thecinematography by Masamichi Sato, on the other hand, is consistently effectivethroughout and makes you glad that the film was not shot in colour. Sweet Secret was the penultimate film ofKozaburo Yoshimura, who lived until the year 2000, but whose ill health madeworking difficult for him in his later years. It’s clear that in this case hewas working on a smaller budget than he had enjoyed in the past, and there’salso a sense that he was struggling to keep up with the times and attempting tomake something more akin to a Yasuzo Masumura film (I suspect that Yoshimuramight have preferred to make this a period drama and the idea of updating thestory from the 1920s to contemporary Japan was likely a condition imposed byShochiku, although it may have been Shindo's idea as he had previously adapted another Shusei Tokuda story as Stolen Pleasure for Daiei and given it a modern setting). In any case, it’s a decent effort of some interest, although notamong the director’s strongest pictures. Perhaps the most intriguing aspect ofthe film is its ambiguity – it could equally be interpreted as the story of ayoung woman who uses men to attain her ambitions or as being about menexploiting a young woman’s ambitions in order to gain sexual favours.

The film appears tohave been shot in 1968, but not released until 1971.

Bonus trivia: The workof author Shusei Tokuda was adapted for the screen on a number of occasions,beginning in the 1920s with a few silent films now lost, followed by KanetoShindo’s Epitome (1953), MikioNaruse’s Untamed (1957) and YasuzoMasumura’s Stolen Pleasure (1962). Tokuda’s novel Rough Living (the basis for Untamed) exists in English translation.

May 27, 2024

Kimi shinitamo koto nakare / 君死に給うことなかれ (‘Don’t Die Before Your Time’, 1954)

Obscure Japanese Film #115

Yoko Tsukasa

Yoko Tsukasa

1940. Baggy-suited university professor Wataru (Ryo Ikebe) falls for Kumiko (Yoko Tsukasa), the nurse looking after his ailing mother in the hospital. However, his best friend, Kojima (Yoshio Tsuchiya), is being sent off to war and wants Wataru to marry his sister, Reiko (Setsuko Wakayama). Wataru resists and, when Kumiko is reassigned to Hiroshima, he follows her but receives a telegram en route ordering him to report for military duty immediately. The two are separated and lose touch with each other amid the chaos of war.

Ryo Ikebe

Ryo Ikebe

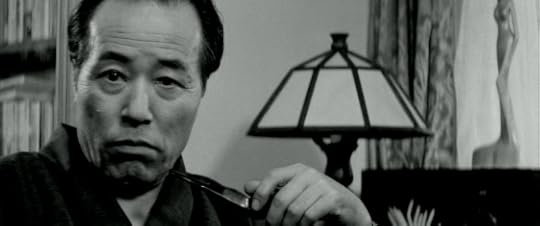

Five years later, Kumiko has survived the A-bomb and is working for a man (Takashi Shimura) who runs a nursery school for orphans in Hiroshima. However, she has radiation burns on her body and the doctors believe there is a strong chance of her developing leukemia. For this reason, she believes that she is no longer fit for marriage and has changed her name in case Wataru tries to find her. In fact, Wataru has already tried to do so and concluded that she must be dead; he has married Reiko, but remains heartbroken. When circumstances lead him to suspect that Kumiko may still be alive, he makes every effort to track her down…

This wartime weepie was originally to star Ineko Arima, but she had to withdraw due to an eye problem and was replaced by Yoko Tsukasa, a Mainichi Broadcasting System employee who had never acted before but had just done her first modelling job and was spotted by director Seiji Maruyama on a magazine cover. Tsukasa proved that she was more than just a pretty face and became an instant star as a result.

Takashi Shimura and Ryo Ikebe

Takashi Shimura and Ryo Ikebe

On the basis of this film, it should be unsurprising that director Seiji Maruyama went on to become best-known for his later war films as, while some scenes are indifferently shot, the movie suddenly comes alive during the impressive action scene in which Wataru and Kumiko have to flee their train along with hundreds of other passengers due to an aerial attack.

Given the storyline, this Toho picture can hardly fail to be moving, and indeed it is, but it also feels rather contrived at times, and the characters often fail to be as sympathetic as they’re presumably supposed to be. Wataru just seems to assume that his feelings are reciprocated by Kumiko and forces himself on her whether she likes it or not, while Kumiko appears to revel in playing the martyr. The film also tries to have its cake and eat it in that Kumiko’s only visible scar from the A-bomb (that we get to see anyway) is on one wrist, making it rather too easy for Wataru to dismiss it (compare this to the scene in A Night to Remember in which Jiro Tamiya is made to feel considerably more uncomfortable). One can’t help feeling that the bombing of Hiroshima in this film is little more than a convenient plot device.

May 20, 2024

Judai no seiten / 十代の性典 (‘Teenage Sex Book’, 1953)

Obscure Japanese Film #114

When high school student Fusae (Yoko Minamida) is excused from PE one day due to having her period, she finds herself opportunistically stealing the wallet of a classmate, Eiko (Ayako Wakao). She’s caught in the act by a male student who tries to blackmail her into kissing him. When she refuses, he grasses her up to the teacher, who tells Fusae not to be too hard on herself as many women do strange things when in this condition.

Yoko Minamida

Yoko Minamida

Later, Fusae finds 10,000 yen in the street and gives 1000 to her father (Eijiro Tono) to pay the overdue electricity bill as he is being threatened with disconnection. Feeling that she had no right to this money either, Fusae is tormented by feelings of shame and decides that she needs to get a job, so she seeks help from Machiko (Ikiru’s Miki Odagiri), a friend who has already left school and is selling fish door to door.

Meanwhile, 17-year-old Eiko has a crush on older female friend Kaoru (Akiko Sawamura), a senior student who is secretly dating Nitta (Ken Hasebe), a male art student. However, Kaoru does not allow Nitta to touch her as she has a fear of men, perhaps partly because she’s a Christian and believes she will go to Hell if she has sex before marriage. Asako (Yuko Tsumura), on the other hand, is a free and easy hedonist who is also in love with Nitta. When these three go ice skating together as part of a larger group, tragedy strikes…

This is a strange little film that comes across as some kind of Christian propaganda intended to persuade young women to hang on to their virginity until they are married; Ayako Wakao’s character even converts to Christianity at the end. Today, the film seems quaint and even ludicrous at times. For instance, it suggests that it’s perfectly normal for women to become kleptomaniacs when menstruating, and the strange sound effect we hear whenever a man gets too close to Kaoru soon becomes unintentionally comical.

The supporting cast includes Haiyuza Theatre founders Koreya Senda, Eijiro Tono and Eitaro Ozawa as the fathers of the main female characters, but the film will be of most interest today for fans of Ayako Wakao. According to Japanese Wikipedia, this film gave Wakao her breakthrough role and ‘received considerable criticism from educators, newspapers, and magazines, and for many years it was treated as taboo in interviews.’ If true, it’s hard to see why Teenage Sex Book was considered so controversial – the salacious title disguises a film which seems innocuous today and, although it was unusually frank regarding sexual matters for its time, there is nothing in it that seems designed to titillate. In any case, it clearly made money for Daiei studios as they turned it into a series and produced three follow-up films, although these were not direct sequels but separate stories with new characters. It’s also worth noting that Ayako Wakao cannot really be said to have the star role here – she is part of an ensemble, as can be seen from the fact that Yoko Minamida and Miki Odagiri also appeared alongside her in all of the sequels. Anyway, it’s fun to see Wakao at this early stage in her career, and she even engages in a little slapstick and executes an impressive pratfall at one point. Her real breakthrough role, though, was surely in Kenji Mizoguchi’s Gion Bayashi (aka A Geisha) the same year.

The fate of the film’s other star, Akiko Sawamura, remains something of a mystery – she appeared in the first sequel, then changed her name to Michiko Sawamura and made a few more films for Daiei before disappearing from the screen in 1954, after which she surfaced just one more time, appearing in The Story of Iron-Arm Imao, a baseball movie directed by Ishiro Honda for Toho in 1959.

Director Koji Shima (1901-86) was a former leading actor of the 1920s and ‘30s who worked frequently for directors Kenji Mizoguchi and Tomu Uchida. Most of these films are now lost, with Uchida’s Sweat (1929) being a notable exception. As a Daiei contract director during this period, it’s no surprise to learn that he also directed Wakao in ten other films including The Phantom Horse (1955). However, his most widely-seen film is Warning from Space (1956).

May 14, 2024

The Human Wall / 人間の壁/ Ningen no kabe (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #113

Kyoko Kagawa

Kyoko KagawaFumiko (Kyoko Kagawa)is a teacher at an elementary school in Saga Prefecture in the south of Japan.Her pupils are mainly from poor families in which the men are employed at thenearby coal mine or work as fishermen. When the local council wants to cutcosts by laying off 259 staff, Fumiko comes under pressure to resign from herbosses, who explain that, as she is married, she has her husband’s income tofall back on, and that’s why they’ve singled her out. However, the real reasonis that they suspect her husband, Kenichiro (Shinji Minamibara), of being acommunist. Fumiko loves her job and refuses to resign. Kenichiro is anexecutive committee member of the local teacher’s union, but he’s a careeristrather than an idealist, and the relationship between the couple worsens whenhe wants to use their savings to bribe an official so that he can get electedchairman.

Shinji Minamibara

Shinji Minamibara Jukichi Uno

Jukichi UnoMeanwhile, Fumiko’scolleague Sawada (Jukichi Uno) has troubles of his own – catching three of hispupils bullying a disabled classmate, he pushes them away, but then finds himselfaccused of assault. This situation is exploited by the Liberal DemocraticParty, who attempt to use him as a political pawn. The school’s other self-sacrificingteachers also continue to be treated unfairly, but eventually – led by Fumiko –they learn the power of collective action…

Kyoko Kagawa

Kyoko KagawaBased on a novel byTatsuzo Ishikawa (1905-85) which was itself based on real events that occurredin 1957, this independent production was made by director Satsuo Yamamoto’s owncompany and financed by the Japan Teachers’ Union, who were encouraged by thesuccess of Yamamoto’s previous film (Balladof the Cart-Puller) and the fact that he had a distribution deal with Shin-Toho.After being blacklisted by the studios as a communist in 1950, Yamamoto hadmanaged to produce a number of high-quality and often commercially-successfulfilms mostly financed by unions – a remarkable feat which would eventually see himre-employed by the studios, who could not ignore his impressive track record. In 1962, he made the hugely successful Shinobi no mono for Daiei, launching both the ninja genre and a series which ran to nine films, the first three of which are soon to be released on Blu-ray by Radiance Films.

One reason that The Human Wall is languishing inobscurity today may be that the topical nature of the material appears to makeit of little contemporary relevance. However, I would argue that similar thingscontinue to happen to people today and the film still works well as aneffective piece of drama. At the time, it was a critical as well as acommercial success, ranked 6th best film of the year by Kinema Junpo and winning three MainichiFilm Concours awards: Jukichi Uno for Best Supporting Actor, Yamamoto for BestDirector (for this and Ballad of theCart-Puller) and Hikaru Hayashi for Best Score (for this, Ballad and Lucky Dragon No.5). It’s a shame that Kurosawa favourite KyokoKagawa was overlooked, as she gives an excellent performance and carries thefilm in what must be one of her best movie roles. At the time of writing,Kagawa is still with us at the age of 92 and has only recently retired.

Eitaro Ozawa

Eitaro Ozawa Tanie Kitabayashi

Tanie Kitabayashi Masao Mishima

Masao MishimaAmong the familiarfaces in the supporting cast are Ken Utsui, Eijiro Tono, Eitaro Ozawa, TaijiTonoyama, Tanie Kitabayashi, Masao Mishima, Teruko Kishi and Yunosuke Ito, butthe most surprising performance for me was that of Sadako Sawamura, an actressI can only remember previously seeing as downtrodden types, but who here playsa strong, no-nonsense woman most effectively.

Sadako Sawamura

Sadako SawamuraDirector SatsuoYamamoto sometimes phoned it in when working on later studio assignments suchas Zatoichi the Outlaw (1967) and The Peony Lantern (1968), but he clearlytook a lot of care over projects close to his heart such as this one, and itshows, especially in his sensitive direction of the child characters and hisimpressive skill in the way he manages to coordinate large groups of them onlocation. While this film could easily have been a worthy bore, good work inall departments prevents this from being the case, and the excellent cast bringtheir characters vividly to life.

Bonus trivia: Author TatsuzoIshikawa also provided the literary sources for the later Yamamoto films Kizudarake no sanga (aka The Tycoon, 1964) and Kinkanshoku (1975).

May 4, 2024

Summer Storm / 夏の嵐 / Natsu no arashi (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #112

Masahiko Tsugawa and Mie Kitahara

Masahiko Tsugawa and Mie KitaharaDirector Ko Nakahira’sfirst film following his famous ‘sun tribe’ movie Crazed Fruit again stars Mie Kitahara and examines the lives ofdisaffected youth in post-war Japan. The film opens dramatically with a briefbut attention-grabbing pre-credits sequence in which we hear a startling screamfrom Kitahara, who is standing on a windy beach and shouting out to sea. “Howunfair! You’ve gone forever, that’s so unfair. I’ll never forgive you for this!Never!” she yells before rushing into the stormy ocean. This scene is repeatedagain at the end of the film, by which point of course we have the context tounderstand it.

Ryoko (Kitahara) is a young womanliving with her family after having been raised by another woman they call‘Aunt Maki’ (Ayuko Fujishiro) until she was 13, at which point Aunt Maki remarriedand sent Ryoko back to her birth mother, Mitsu (granny-specialist TanieKitabayashi playing her real age for once).

As a result, Ryoko not only feelsunwanted by both women and resents them, but has grown up to be a cold andcynical person. Although she works as a teacher at a special needs school, it’sa job she has taken mainly because her parents were against it (for reasonswhich are unclear). The family live in a Western-style house and are practisingChristians. Mitsu takes religion especially seriously and is insufferablyself-righteous; Ryoko sees her sister Taeko (Yoko Kozono) as a carbon copy ofher mother and despises her for this reason. Their father (Yo Shiomi) is anantiques collector with his head in the clouds most of the time, and the onlyfamily member Ryoko feels any kinship with is her younger brother Akira (MasahikoTsugawa), mainly because he’s adopted.

Into this already dysfunctionalhousehold steps Akimoto (Tatsuya Mitsuhashi), a young man who is newly-engaged toTaeko. He’s full of self-loathing after having survived a suicide pact with aformer girlfriend who died. When Ryoko is introduced, she suffers a shock – bypure coincidence, Akimoto is the same man she once had a one-night stand withon a camping trip. Trouble begins when the two realise they still have feelingsfor each other…

Tatsuya Mihashi

Tatsuya MihashiIn an attempt to follow the hugesuccess of Crazed Fruit (based on aShintaro Ishihara story), Nikkatsu studios chose to adapt another controversialAkutagawa Prize-nominated story by an angry young author – in this case afemale one, Michiko Fukai (1932-2015). This is the only one of Fukai’s storiesto have been filmed, and her literary career seems to have been a short one. Tomy knowledge, none of her stories have been translated into English. Althoughinformation about Fukai is scarce on the web, she was apparently influenced by LuchinoVisconti’s portrayal of self-destructive emotions in Senso (1954), which had been released in Japan as Natsu no arashi, or Summer Storm, and whose title she borrowed.

Tatsuya Mihashi and Yoko Kozono

Tatsuya Mihashi and Yoko Kozono

The film features aconsiderable amount of voiceover narration by star Mie Kitahara, and is quite adialogue-heavy piece of work in itself. It’s extremely well-directed by Ko Nakahira,who helps to hold the interest with some unusual staging; for example, he hasKitahara play a whole scene lying face down on the floor at one point, while inanother, Ryoko and her colleague Kido (Nobuo Kaneko) exchange lines in asweltering staffroom while each try to commandeer the one electric fanavailable. Unfortunately, Ryoko and Akimoto are both such self-pityingcharacters that they soon grow tiresome, and they are also given to sayingthings like “I crave exhilarating drama that makes my head reel!” (Ryoko).Perversely, it’s only when Akimoto realises that Taeko doesn’t love him that hewants to marry her. “You can’t understand my delight at the living death shepromises me!” he exults. It’s hard to imagine real people saying such things,and I doubt it would sound any less pretentious in Japanese as thesubtitles by Stuart J Walton are excellent. For these reasons, the filmultimately left me cold, and I suspect that it was a good deal lesswell-received than Crazed Fruitconsidering that it’s nowhere near as well-known and there were no furthercollaborations between Ko Nakahira and Mie Kitahara, or adaptations of MichikoFukai’s stories. Where Crazed Fruitsuccessfully tapped into the zeitgeist, Ryoko and Akimoto are both a bit tooweird for most people to relate to; consequently, Summer Storm’s themes of suicide and incest feel like a slightlymisjudged attempt to appeal to the supposedly nihilistic and rebellious youth of the time throughmere shock value.

Bonus trivia: Mie Kitahara (b.1933)was one of Japanese cinema’s biggest stars of the late 1950s and is still aliveat the time of writing. After making 20 films with fellow star Yujiro Ishihara in the space of five years, she married him andretired from films in 1960, subsequently appearing in only one TV drama in1964. Known as Makiko Ishihara since she quit acting, she co-managed herhusband’s production company for many years and continued to run it after his death in1987.

April 27, 2024

The Great Villains / 大悪党 / Dai akuto (1968)

Obscure Japanese Film #111

Yoshiko (Mako Midori)is a naïve country girl now living in Tokyo as a student. As she doesn’tbelieve in sex before marriage, her boyfriend gets frustrated and dumps her ata bowling alley. Seeing her left alone, Yakuza scumbag Yasui (Kei Sato) seizesthe opportunity and slithers over to her. He takes her to a bar where he slipsher a spiked drink, then takes her back to his apartment, rapes her and photographsher naked while she’s unconscious. When she awakes the next morning, he’s stillasleep, so she leaves quietly, but within a few days he arrives at herapartment and shows her the photos, threatening blackmail. However, he offersto give her the negatives and all copies if she will sleep with pop idol TeruoShima (Isao Kuraishi), explaining that Shima will pay him for providing abeautiful woman he can have no-strings sex with. Having no other choice,Yoshiko agrees but, when she goes to meet Shima, Yasui is hiding in theapartment filming them. Although Yasui keeps his promise and returns the photosand negatives to Yoshiko, she now has the film to worry about instead. Meanwhile,Yasui pays a visit to Shima to blackmail him, but Shima’s manager (Asao Uchida)hires unscrupulous lawyer Tokuda (Jiro Tamiya) to make the problem go away. Yasuifinds that Tokuda is not easily intimidated – has he finally met his match?

This Daiei productionwas based on the novel Akutoku bengoshi(‘Unscrupulous Lawyer’) by Masaya Maruyama (1926-2004), who also provided thesource material for director Yasuzo Masumura’s A Wife Confesses (1961). The fact that Maruyama was himself alawyer is unsurprising considering that Tokuda’s legal shenanigans in the filmseem unusually well thought-out, even if certain other aspects of the story donot entirely convince, such as Yoshiko’s rather sudden transition at the end.Some of the violence is not terribly convincing either, and we have scenes ofslapping where there is clearly no contact but the patented sound of whatsounds like a whiplash on sheet metal is dubbed on.

It’s impossible not tofeel sympathy for Yoshiko, which begs the question of whether the police wouldreally be as rough on a woman in such circumstances as they are here. EvenYoshiko’s mother seems to care little for her daughter’s welfare, and is farmore concerned that Yoshiko has disgraced the family. It’s debatable to whatextent these elements reflect real cultural differences or are clichés commonto Japanese drama – certainly, similar scenes can be found in many otherJapanese films of the era.

Although not one ofYasuzo Masumura’s most impressive films, TheGreat Villains has a compelling story and three strong lead performances,with Jiro Tamiya in another of the slippery manipulator roles he played so welland Kei Sato equally convincing as one of the most loathsome characters I’veseen in a film for some time. Mako Midori, who resembles Mie Kitahara here, hasprobably the most difficult role and uses her eyes and body language mosteffectively in a part which gives her only limited opportunities for dialogue. Shehad just been fired from Toei at the time for complaining about the types ofroles she was being obliged to play; she later went on to star in Masumura’s Blind Beast (1969).

The surprisingly statelyclassical music score by Tadashi Yamauchi suggests an attempt to lend the film bothclass and gravity, although Daiei’s dwindling budgets at the time are evidentin the almost anonymous supporting cast and the fact that the work of Masumura’sregular cameraman Setsuo Kobayashi is less impressive than usual. Nevertheless,this is good second-tier Masumura worth seeking out for fans of the director,the three stars or Japanese crime dramas in general.

Note on the title: Asthere are no plurals in Japanese, it is debatable whether the title should betranslated as The Great Villains or The Great Villain. Perhaps because thefilm is also known as The Evil Trio,whoever gave the film its English title has chosen the plural version. However,while the character of Yasui clearly qualifies as a villain and this term couldalso be applied to that of Tokuda, it certainly doesn’t fit Yoshiko unless intended ironically.

April 17, 2024

The Great Journey / 大いなる旅路 / Oinaru tabiji (1960)

Obscure Japanese Film #110

Rentaro Mikuni and Michiko Hoshi

Rentaro Mikuni and Michiko Hoshi

Morioka, IwatePrefecture, mid-1920s. Kozo Iwami (Rentaro Mikuni) works for the railway as astoker but wants to become a driver. After failing the exam, he becomesdespondent and seeks solace in saké and the arms of bar hostess Koharu (MichikoHoshi).

One day, Yukiko (Akiko Kazami), a young woman rushing home to see adying relative, is permitted to ride the freight train on which Kozo isworking. This chance meeting leads to marriage, but Iwami fails to change hisways and continues seeing Koharu, hardly even bothering to hide the fact fromhis wife. However, when an avalanche causes Kozo’s train to derail and thedriver is killed, Kozo undergoes a personality change.

It’s not entirely clearwhy this occurs, but perhaps it’s just due to the fact that he now realises howlucky he is to be alive. In any case, he stops seeing Koharu and begins takinghis job more seriously, eventually becoming a driver as a result.

The yearspass, and Kozo and Yukiko have four children: Tadao (Hiroshi Minami), who getscalled up for military service in China and is soon killed; Shizuo (KenTakakura), who follows in his father’s footsteps and joins the railway; Sakiko(Mitsue Komiya), who marries the wrong type of guy; and Takao (Katsuo Nakamura),who voluntarily enlists in the army but later returns embittered and in poorhealth.

Spanning three decades,this features Mikuni in another role in which he has to age considerably overthe course of the movie, as he had previously done in Stepbrothers (1957) and Balladof a Cart-Puller (1959). However, this was the first time he had won an awardfor such an effort, namely the Blue Ribbon for Best Actor. Kozo is a complexcharacter and our feelings about him change as the story progresses; at first, seeinghim as an uncouth worker in a wintry location who gets passed over forpromotion, I thought he was going to be another Gonsuke from A Story from Echigo. However, though hecan be unforgiving and even violent at times, Kozo usually regrets his actions almostimmediately and sometimes displays a generosity of spirit. Mikuni made anotherrailway picture, Oinaru bakushin, forthe same director, Hideo Sekigawa, later the same year, but he played adifferent character and the stories were not connected, although bothscreenplays were written by – you guessed it (or not) – that one-manscreenplay-machine, Kaneto Shindo. While many of Sekigawa’s films appear tohave been routine assignments, he directed a couple of notable anti-war films: Listen to the Voices of the Sea (1950)and Hiroshima (1953), and he does agood job here, with the location shooting being particularly impressive, althoughthe story has not dated well and must have seemed old-fashioned even at thetime.

The first half hour ofthe film is the most interesting – once Kozo changes his attitude after theaccident, it becomes a sentimental family saga which unfolds all toopredictably, while Ichiro Saito’s music lays on the harps and strings a bitthick. Like the previous film I reviewed, this is another with a stronglyconservative message: everyone learns the error of their ways, and hard workand dedication to duty are rewarded in the end. This ideology is especiallysurprising coming from a couple of leftists like Sekigawa and Shindo.

Perhaps the mostimpressive thing about the film is the fact that they actually wrecked a realtrain in order to make it, a feat made possible due to Toei president HiroshiOkawa, a former railroad employee who had maintained good connections withJapan’s national railway.

Note on the title: The film is sometimes referred to as 'The Great Road', which makes little sense as tabiji means 'journey' rather than 'road'. It's also clear from the film that 'journey' has the double meaning of a railway journey and the journey of life.