A Portrait of Shunkin / 春琴抄 / Shunkinsho (1976)

Momoe Yamaguchi

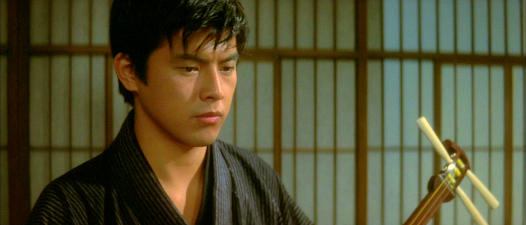

Momoe YamaguchiDoshomachi, Osaka,early Meiji era (c.1870s). Okoto (Momoe Yamaguchi), the youngest daughter of thewealthy owner of a wholesale medicine company, has lost her sight due to achildhood illness. She takes a liking to Sasuke (Tomokazu Miura), a youngapprentice employed by her father, and soon he is the only person she willallow to escort her to her music lessons and help her with other tasks. Okoto becomesproficient at playing the instrument whose name she shares (the koto, the ‘O’ being a polite prefix),inspiring the devoted Sasuke to take up the more humble samisen, which hepractises in secret.

Initially, Sasuke gets into trouble for being more concernedwith looking after Okoto and learning music than he is about learning the trade.However, Okoto has become extremely stubborn and difficult to deal with sincelosing her sight, so her parents decide to release Sasuke from his normalduties and allow him to be Okoto’s full-time companion – even paying for him tohave music lessons from Okoto’s teacher – in the hope that this will soothe heranger and improve her character. Meanwhile,Okoto’s beauty has led to her attracting the attention of wealthy playboy Minoya(Masahiko Tsugawa), who begins laying plans to seduce her…

Yamaguchi with Masahiko Tsugawa

Yamaguchi with Masahiko Tsugawa

Later in the story,Okoto becomes a music teacher herself and takes the name of Shunkin, hence thetitle. Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1933 novella of the same name (available in a goodEnglish translation in the collection SevenJapanese Tales) was first filmed in 1935 by Yasujiro Shimazu in a versionstarring Kinuyo Tanaka. At the time, talking pictures were still relatively newin a Japan which was lagging a few years behind Hollywood in this department.As the story features both music and birdsong quite prominently, it must haveseemed a good choice by which to exploit the possibilities of the new soundmedium. Other versions followed: in 1954, Daisuke Ito directed Machiko Kyo asOkoto, while in 1961 Teinosuke Kinugasa made a third version starring FujikoYamamoto. Up to this point, each film had featured a big female star, with therole of Sasuke being played by a more minor male co-star. Kaneto Shindo brokethis pattern in 1972 with his version, entitled Sanka (‘Hymn’), which featured the unknown Tokuko Watanabe in therole. Shindo also restored the novella’s framing device, which uses afirst-person narrator visiting the graves of Okoto and Sasuke and meeting theirformer maid – now an old woman – whom he persuades to tell him their story. In Sanka, Shindo himself plays thenarrator, while his mistress Nobuko Otowa takes the role of the maid, so itseems likely that Shindo followed the book in this regard mainly to provide arole for Otowa, who was too old to play Okoto.

Given that Okotocontinues to treat Sasuke like a servant even after they become lovers and isoften cruel to him, Tanizaki’s story can equally be interpreted as a story of howSasuke’s unwavering devotion represents the ideal of true love, or as a storyabout the perfect sado-masochistic relationship. Unlike the previous film versions, Shindo’svery much emphasizes the latter reading, even going so far as to have Sasukereverently burying his mistress’s shit in the garden every day – a detail not presentin the book. However, considering that Tanizaki’s title was not Okoto and Sasuke but A Portrait of Shunkin, it’s alsopossible that his main concern was to provide a character study of a womanwhose sense of pride means that she absolutely refuses to behave like a victimand for that reason would rather be thought cruel than allow anyone to feel sorryfor her.

Made just four yearslater, director Katsumi Nishikawa’s 1976 version – the fifth – returns to themore conventional interpretation of the tale as a tragic love story, with ascreenplay co-written by Nishikawa and Teinosuke Kinugasa, who had directed the1961 version. A lot of care evidently went into the making of this one, and it’svery pretty to look at. Its raison d’etre was clearly to provide a vehicle forstars Momoe Yamaguchi and Tomokazu Miura. Yamaguchi – who first came to fame asa 13-year-old pop singer in 1972 – was such a phenomenon in Japan in the 1970sthat she even has a chapter devoted to her in Mark Schilling’s Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture.Her first major film part was in a version of another oft-filmed literary work,Yasunari Kawabata’s The Izu Dancer in1974, the first of seven films for director Katsumi Nishikawa but also, more significantly, the first of 12 features in which she co-starred with TomokazuMiura. The two soon became known as the ‘golden combination’, and were marriedin 1980, at which point Yamaguchi retired from show business to become afull-time wife and mother but continued to be hounded by both the media and herobsessive fans.

Yamaguchi and Miuragive decent performances in A Portrait ofShunkin, as do the rest of the cast, and it’s a well-made film. However, withMasaru Sato’s syrupy music ladled all over the soundtrack, I found its prettysentimentality a bit cloying for my taste and prefer Shimazu’s early attempt oreven Shindo’s more eccentric take on the story.