Holly Tucker's Blog, page 8

December 15, 2016

Cartesian Feminism

By Richa Bijlani (Guest Contributor)

In a time where declaring yourself as a feminist also makes you a radical, it’s necessary to understand where the fight for gender equality began. Although the term “feminism” wasn’t coined in English (from the French féminisme) until around the end of the 1800s, discussion on equality of the sexes dates back to Plato in ancient Greece. However, these debates were not focused on equal wages or access to birth control; they were simply disputing whether or not women were even humans.

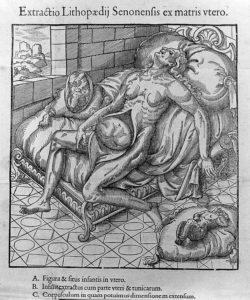

In France, François Poulain de la Barre was one of the earliest philosophers to argue for social equality between women and men (1647-1725). In response to opponents of equality, Poulain de la Barre borrowed Cartesian ideas to object the alleged lack of natural ability of women instead of appealing to the authority of the Bible or ancient texts, as many of his contemporaries did. Following René Descartes’ proposed split between body and mind, Poulain de la Barre concluded, “the mind has no sex.” In terms of the body, he found that other than bodily functions involved in pregnancy, the differences between the physicality of women’s and men’s bodies were not relevant to their exclusion from social, political, and economic affairs.

The idea of dualism, suggested by Descartes, distinguishes between the physical aspect of the body and the consciousness of the mind. Poulain de la Barre took this idea a little further in asserting that in body and mind women should be considered just as competent as men (“women are as noble, as perfect, and as capable as men”). In his effort to change the discourse surrounding gender equality, Poulain became the first Cartesian feminist. So why, then, were women still assumed to be the subordinate sex?

Much ahead of his time, Poulain de la Barre suggested that sexual inequalities do not stem from nature, but from customs and traditions. In his three essays On the Equality of the Two Sexes, On the Education of Ladies, and On the Excellence of Men written between 1673-1675, Poullain de la Barre analyzes common prejudices associated with women, suggesting that they stem from the historical isolation of women to the domestic sphere and not from their inherent lack of ability. He attacks the validity of these prejudices by essential saying that just because this is the way things have always been doesn’t mean that’s the way they should be.

The oppression of women, he argues, leads to their exclusion from positions of power in society. Poulain de la Barre advocated for equal educational opportunities that would allow for women to hold public offices. However progressive his ideas were in the 17th century, Poulain receives little attention as a precursor to the feminist movement that developed later in the 18th century period of Enlightenment. Nonetheless, we must not forget that men, like Poulain de la Barre, can in fact be feminists.

Bibliography

Audier, Serge. “”De l’égalité des deux sexes. De l’éducation des dames. De l’excellence des hommes” et “Des femmes en Amérique” : Pionniers de l’émancipation.” Le Monde.fr. Le Monde, 16 June 2011. Web.

Barre, François Poulain de la, Marcelle Maistre Welch, and Vivien Elizabeth Bosley. Three Cartesian Feminist Treatises. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2002.

Clarke, Desmond, “François Poulain de la Barre”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

New World Encyclopedia Contributors. “Feminism.” New World Encyclopedia. New World Encyclopedia, 25 Mar. 2016. Web.

Richa Bijlani is a senior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. She studies Anthropology as well as Neuroscience and French.

The post Cartesian Feminism appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 14, 2016

Champagne’s Three Slopes, Saint-Evremond, and the Invention of Snobbery

By Thomas Parker, regular contributor

Champagne owed its initial cachet not merely to the quality of the wines, nor to the fact that they were effervescent (a relatively new phenomenon, historically speaking), but mostly to their close proximity to Paris, which made for convient consumption by France’s kings. But sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sources also attest that Champagne’s influence grew further afield, with the wine from the Champagne town of Ay, in particular, obtaining international acclaim. Sources reported that Pope Leo X of Italy, Charles V of Spain, François I of France, and Henry VIII of England were all particularly fond of the wines from Ay. The vin d’Ay didn’t really catch on, however, until the second part of the seventeenth century when the period’s best-known connoisseur and bon vivant, Charles de Saint-Evremond, joined the party.

The town of Ay, located outside of Épernay

Saint-Evremond was from a noble Normand family, and first made a name for himself as an accomplished career soldier in the early part of the century. During the 1650s, he began frequenting elite Paris circles where he became even more known for his repartee and wit, a trait that eventually got him exiled to England when it was discovered that he was the author of a bit of satirical writing skewering the Cardinal Mazarin, Louis XIV’s Chief Minister. Before leaving France, however, he and two other cronies established what amounted to Saint-Evremond’s most enduring distinction: that of an incorrigible food and wine snob. The three were so persnickety in their tastes, as the story goes, that they would only consent to drink wine issuing from three specific slopes in Champagne. Word of this spread and people began referring to them as the three Côteaux, or “Slopes.”

Rather than taking offense, the Côteaux seemed to relish the moniker, bandying it about town in reference to themselves and fanning the mix of fame and notoriety their reputation started to bring. A satire from the period, entitled Les Côteaux ou les Marquis Friands, claimed that “Of today’s aficionados, [the Côteaux] are the most elite and distinguished. Presented with game, they can tell by the smell its place of provenance.” The Bishop of Lemans added to this image in a chiding tone, “These men (…) can only eat river veal: they must have partridges from the Auvergne; their rabbits must be from the Roche-Guyon or Versine, and as for wine, they can only drink that from three slopes of Ay, Hautvilliers, and Avenay.”

It was not just the men’s choosiness that was important, but also what they chose. In each of the selections, from the river veal, reputed to be the most tender available, to the wines, the emphasis was on a set of qualities, including whiteness, lightness, delicateness, and purity, that began to pop up everywhere where food was praised in the second half of seventeenth-century.

Champagne became the very icon and pinnacle of good taste in this regard. Following in the footsteps of France’s royal tradition, Saint-Evremond, who deemed the wines of Ay superior to the two other slopes, allowed that:

“If you ask which of these wines I prefer, without allowing me to stray to the taste trends inspired by the false connoisseurs, I would say to you that the good wine of Ay is the most natural of all wines, the healthiest, and the most purified of any odor of terroir, and of the most exquisite pleasurability in its flavor of peaches, which is unique to it, and the best in my opinion of all flavors.”

Champagne Gosset from Ay is the oldest champagne house in France.

The “false connoisseurs” in question were those who sought effervescent versions of champagne, a quality frowned upon by traditionalists at the time.

What is perhaps most striking is that Saint-Evremond and the Côteaux, as early seventeenth-century prototypes of today’s supertasters and wine snobs, did not gravitate toward the specificity and authenticity of the terroir as would contemporary wine connoisseurs.

Rather, along with a proclivity for all that was light and white, they sought foods washed of any flavors that would be identified with the earth. Instead of representing an unadulterated expression of place, the most exquisite, cosmopolitan, and refined foods and wines were paradoxically thought purest if they were both place specific and rang of no place.

The post Champagne’s Three Slopes, Saint-Evremond, and the Invention of Snobbery appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 13, 2016

Caught in the Crossfire: Paris’s Modernization and Louis Le Vau’s Controversial Legacy

By Jack Robey (Guest Contributor)

Portrait of Louis Le Vau, 1662

While many know Louis Le Vau for his architectural accomplishments, few are aware of the lawsuit that haunted him at the end of his life. Le Vau rose to the prestigious position of Surintendant des Bâtiments, translated as superintendent of buildings, under King Louis XIV. While Le Vau is best known for his renovations of Versailles, his work at the Louvre, various hôtels particuliers and at Nicolas Fouquet’s Vaux-le-Vicomte château has contributed to France’s share of famous architecture. While his final project was designing Versailles’s Enveloppe from 1668 to 1670, when he died, Le Vau’s work on the Collège de Quatre-Nations in Paris has left him a controversial legacy.

The dispute regards Le Vau’s design and construction of the Collège de Quatre Nations, which became part of the Université de Paris and is today part of the Sorbonne. Le Vau was accused of embezzling funds by King Louis XIV’s Minister of Finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who opposed Le Vau’s architectural plans for the site. Funds for the Collège had been left by Cardinal Mazarin, who wanted further development and consolidation of royal power in Paris.

Styles of architecture were in the midst of a shift during the late-17th century in France. The conflicting classical and baroque styles, favored by Colbert and Le Vau respectively, represent the modernization and growing sophistication of the French capital city. Some have called the Collège a “Baroque building in a classical city,” and its influence on central Paris was significant. Situated across the river Seine from the King’s new apartments in the Louvre, it meant that Le Vau’s designs would occupy both sides of the river as well as at Versailles.

Etching of the Collège de Quatre-Nations, Israel Silvestre, 1670

Although the lawsuit wasn’t resolved by the time of Le Vau’s death in 1670, Le Vau’s designs for the Collège were carried out by his pupil, Francis d’Orbay. Colbert objected to the turning of attention from Paris to Versailles, believing that further development of Paris would be more beneficial to the monarchy’s image than construction of an isolated palace. However, Louis XIV ultimately had the last word in this matter.

Le Vau was bankrupt at his death, leaving his wife and daughters in debt and without anywhere to live. After his death, it became evident through financial records that Le Vau’s management of personal and work-related funds sided on the irresponsible. However, his contribution to France’s architecture remains admirable nonetheless.

Bibliography

Ballon, Hilary. Louis Le Vau: Mazarin’s Collège, Colbert’s Revenge. Princeton: Princeton Architectural, 1999. Print.

Cojannot, Alexandre. :Mazarin et le “Grande Dessein” du Louvre : Projets et réalisations de 1652 à 1664.” Bibliothèque de l’école des Chartes 161.1 (2003): 133-219. Historical Abstracts. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

“Versailles — World Heritage Site — National Geographic.” National Geographic. National Geographic, n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2016.

Jack Robey is a junior at Vanderbilt University working toward a major in Economics and minors in French and Psychology. He is interested in the history of economics and French language and is involved with several student organizations on campus.

Jack Robey is a junior at Vanderbilt University working toward a major in Economics and minors in French and Psychology. He is interested in the history of economics and French language and is involved with several student organizations on campus.

The post Caught in the Crossfire: Paris’s Modernization and Louis Le Vau’s Controversial Legacy appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 12, 2016

Stone Babies: The Lithopedion of Sens

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

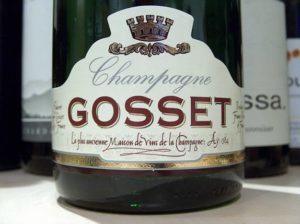

When Colombe Chatry, a tailor’s wife, died in May 1582 at the age of 68, at her husband’s request her body was opened up to discover what had happened to a pregnancy she had started 28 years earlier, which had never come to anything but had left her with years of abdominal pain and loss of appetite. A petrified female fetus was discovered, and was first described by one of those who saw it immediately after its discovery, the physician Albosius (Jean d’Ailleboust), in the Portentosum Lithopaedion of 1582. This work was soon after translated into French by Siméon de Provanchères.

This is one of the very strange but real things which can happen in the female body; in 2015 a story of a calcified fetus made the news, but in that case the woman carrying it was 90 – and alive. In the sixteenth century, how was this rare event understood?

Illustrations of the lithopedion sometimes included a Latin epigram linking it to the ancient Greek myth of the flood, in which the two survivors, Deucalion and Pyrrha, repopulated the world by walking over the earth and throwing stones behind them, which were transformed into living beings. This epigram may be translated as: ‘Deucalion cast stones behind him and thus fashioned our tender race from the hard marble. How comes it that nowadays, by a reversal of things, the tender body of a little babe has limbs more akin to stone?’ While the stones thrown by Deucalion softened to become mortal, the lithopedion had hardened from flesh to stone; contemporary medical writers explained this by suggesting that the cause of the phenomenon was the coldness of the womb.

Display and disappearance

What happened to this prodigy? The lithopedion of Sens was very famous, discussed extensively in its own day, and included in the literature of the monstrous thereafter. The stone fetus was exhibited in several cities of Europe – the midwife Louise Bourgeois, for example, saw it before 1636 in Paris where it was in the possession of a merchant, M. Pretesegle. At this stage, she noted that it was missing one hand, which had remained stuck to the placenta.

In 1653 the lithopedion was in Italy, from where it passed to the cabinet of curiosities of King Frederick III of Denmark, and remained there until its disappearance from the Danish Museum of Natural History some time after 1826. Does anyone know what has become of it?

From curiosity to author

I became interested in the lithopedion when I was studying the eighteenth-century man-midwife, William Smellie. In the first, 1751, edition of his Theory and Practice of Midwifery, Smellie listed the title of the image in a compendium of gynecological writings edited by Israel Spach – Lithopedus Senonensis – as an author. Oops. His rival John Burton pounced on the error, gleefully announcing that, despite six years of preparing the book, Smellie had managed to convert ‘an inanimate, petrefied Substance, into an Author’. Probably all of you who have ever written anything will be able to recall the sinking feeling when you realize you’ve made an slip like this.

The error (quickly corrected for the 1752 edition) and Burton’s attack on Smellie were sufficiently well known to form the basis of a passage in Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy, which appeared in installments between 1759 and 1767. In volume 2, chapter 19, Sterne described how Tristram’s father, ‘who dipp’d into all kinds of books’, looked into ‘Lithopædus Senonesis de Partu difficili, published by Adrianus Smelvgot’ – clearly meant to be Smellie. The footnote states ‘The author is here twice mistaken; – for Lithopædus should be wrote thus, Lithopædii Senonensis Icon. The second mistake is, that this Lithopædus is not an author, but a drawing of a petrified child. The account of this, published by Albosius, 1580, may be seen at the end of Cordæus‘s works in Spachius. Mr. Tristram Shandy has been led into this error, either from seeing Lithopædus’s name of late in a catalogue of learned writers in Dr. —- , or by mistaking Lithopædus for Trinecavellius, – from the too great similitude of the names’. Ouch!

Helen King is Professor of Classical Studies at The Open University. Her most recent book is The One-Sex Body on Trial (2013). She’s recently been devoting most of her time to creating a free online course on Health and Wellbeing in the Ancient World, which runs for six weeks from 6 February 2017. She also tweets as @fluff35, and has a personal blog on which she comments on various aspects of academic life.

The post Stone Babies: The Lithopedion of Sens appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 9, 2016

Male Menstruation in Early Modern Medicine

By Jared Eckman (Guest Contributor)

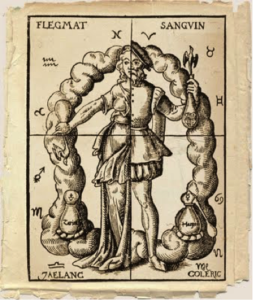

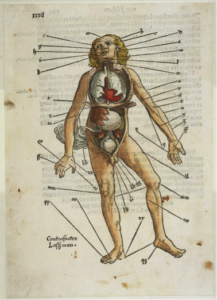

Depiction of the humors.

Few biological processes in humans are as specific to a single sex as menstruation. It is distinctly female with no equivalent in males. However, past theories concerning medicine and gender did not always hold this seemingly apparent opinion. In the early modern era, when Western medical thinking still considered differences between the sexes to be somewhat fluid, many physicians believed men had experiences analogous to female menstruation. Bleedings in males, whether pathological or induced by clinical practices, were thought to rid the body of excess and potentially dangerous blood. To explain such observations, we must first explore the factors that shaped medical thought during this period.

Humorism

When most people think of archaic medical practices that have been abandoned for centuries, blood letting quickly comes to mind. What drove bloodletting’s prevalence and acceptance for over a millennium? The idea that a balance of humors achieves good health, descended from the enduring influence of the Greek physician Galen, directly led to the ubiquitous endorsement of this practice. Humorism, which originated with Hippocrates and was later taken up by Galen, posits the existence of four bodily fluids, or humors: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. If an imbalance occurs, illness ensues. Therefore, to restore the health of the patient, blood was drawn from the body in an effort to achieve equilibrium. Menstruation was often conceptualized as a similar but natural means of ridding the body of excess blood. However, the question of why females, and not males, menstruate still stands.

The various locations for bloodletting.

Male Heat and Female Coolness

Explanations for menstruation were rooted in beliefs concerning male heat and female coolness. Since it was believed that males generated a significant amount of heat–another principle derived from Galen–they would thus be able to burn off the excess materials that women rid of during menstruation. Since females were thought cooler, they were unable to burn excess blood. However, certain males did not generate sufficient heat to return the humors to a desirable balance and must therefore remove excess blood through other means.

Herein lies the basis for reports of male menstruation. For example, the Swiss anatomist Albrecht von Haller, known as “the father of modern physiology,” attributed nosebleeds in males to a physiological attempt to dispel of excess blood. In girls, this fluid found “a more easy vent downward,” as he put it. The belief that male menstruation rids the body of unwanted, illness-inducing blood is also seen in the writings of several 17th century Spanish physicians. Mixing anti-Semitism with science, they claimed that Jewish males menstruate to rid the body of unclean blood in an attempt to demonstrate the racial impurity of Jews. Although these accounts come from a place of prejudice, they nonetheless demonstrate the prevailing early modern belief in male menstruation and its role in ridding the body of unwanted blood.

Bibliography

Beusterien, J. L. “Jewish Male Menstruation in Seventeenth-Century Spain.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 73 no. 3, 1999, pp. 447-456.

Laqueur, Thomas Walter. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1990.

Wiesner, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993.

Jared Eckman is a junior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He majors in Biological Sciences and French and will study in Aix-en-Provence during the spring of 2017. His primary interests include neuroscience, philosophy of medicine, and French literature.

Jared Eckman is a junior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He majors in Biological Sciences and French and will study in Aix-en-Provence during the spring of 2017. His primary interests include neuroscience, philosophy of medicine, and French literature.

December 8, 2016

Feminist Fairies and Hidden Agendas: The Birth of the French Fairy Tale

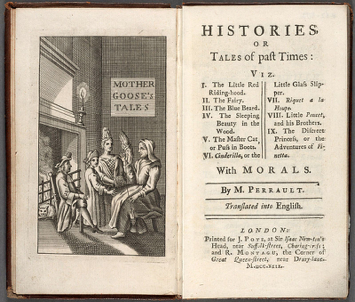

Frontispiece from the 1697 edition of Charles Perrault’s Tales of Mother Goose (from Houghton Library)

By Elizabeth Winter (Guest Contributor)

Today when we think of fairy tales or French contes de fées, we think of Disney princesses, fairies and heroes fighting dragons, with a happy ending and a moral about the power of perseverance or kindness. The origins of the modern fairy tale do not fit so nicely into this modern conception, however. When fairy tales emerged for the first time as a cohesive printed genre in 17th century France, they took on a rather satirical and subversive tone.

Since its beginnings, the fairy tale has been a fluid, almost ephemeral category. Though existing earlier in oral form, the term contes de fées or “tales about fairies” was coined by Countess Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in 1697, when she published her first collection of tales. Though Charles Perrault’s 1697 Tales of Mother Goose remains one of the best-known works of French fairy tales, women like d’Aulnoy actually dominated and developed the genre.

Portrait of Mme d’Aulnoy

Nurtured by d’Aulnoy and her aristocratic contemporaries like Henriette-Julie de Murat and Marie-Jeanne l’Héritier, fairy tales blossomed in literary salons. They were written by women, for women. Though they lacked political or social influence in the period, female authors still produced two thirds of the fairy tales written between 1690 and 1715.

Soon, the term “fairy tale” became a declaration of resistance against the 17th century literary and social status quo. D’Aulnoy’s term signaled the arrival of a genre dominated by women, both in terms of its female authors and the powerful goddess-like characters they created.

How did largely disenfranchised women develop such a powerful genre and literary influence in this constricting period? One explanation is that early fairy tales were passed orally through families and were therefore widely accessible to individuals across gender and class. Even with less education than their male counterparts, women would have had equal knowledge of this common mythology. Women may even have had greater access to these stories, as females were typically associated with storytelling, likely because of their domestic and child-rearing duties allowing them to harness the tales and put them into print.

Illustration for Mme d’Aulnoy’s “La Chatte Blanche”

The imaginary and supernatural focus of the genre itself also provided women the opportunity to separate from the conditions of their everyday life. In the tales they could claim greater power and agency for themselves and their female characters. In magical fairy realms women, like the wealthy and powerful white cat-woman in d’Aulnoy’s La Chatte Blanche or Princess Felicity who rules an island that is impervious to man’s control in “L’Ile de la Félicité,” could at last hold social and political power.

Unlike everyday life, the realms of fairy tales were not regulated by France’s Catholic religion, Louis XIV’s monarchy or strict social expectations. In fact, the tales often undermined and offered veiled critiques of these institutions, depicting the royal court and the church as either too extravagant or impotent. The utopias the authors or conteuses created were simultaneously defiant of the contemporary social conditions, while seemingly innocuous (and able to go unpunished) because they seemed mere fancy.

Most powerfully, the fairy tales reveal the desire of 17th century women to alter their circumstances and express themselves. Just as the fairies in their tales possess powers to determine human fate and uphold a moral code, the conteuses used their tales to begin to guide others towards a more ideal society in which women could possess influence and agency.

Bibliography

D’Aulnoy, Madame. Le Cabinet des fées: Tome 1, Contes de Madame D’Aulnoy. Comp. Elisabeth Lemirre. Arles (France): Editions P. Picquier, 1994.

Jones, Christine Anne. Noble Impropriety: The Maiden Warrior and the Seventeenth-Century Conte de Fées. Diss. Princeton University, 2002. Web. 27 Nov. 2016.

“L’Île de la félicité de Mme d’Aulnoy: le premier conte de fées littéraire français du roman histoire d’Hypolite, Comte de Duglas (1690).” Merveilles & Contes, vol. 10, no. 1, 1996, pp. 87–116.

Murat, Henriette-Julie De Castelnau. A Trip to the Country. Ed. Perry Gethner and Allison Stedman. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2011.

“The Story of Adolphus, Prince of Russia: An Anonymous Translation (1691) of Mme d’Aulnoy’s ‘L’Île De La Félicité’ (1690) The First Literary Tale in the English Language.” Merveilles & Contes, vol. 10, no. 1, 1996, pp. 117–144.

Tucker, Holly. Pregnant Fictions: Childbirth and the Fairy Tale in Early-modern France. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2003.

Zipes, Jack. “The Meaning of Fairy Tale within the Evolution of Culture.” Marvels & Tales, vol. 25, no. 2, 2011, pp. 221–243.

Elizabeth Winter is a junior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. She studies English Literature and Political Science, with a minor in French.

Elizabeth Winter is a junior at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. She studies English Literature and Political Science, with a minor in French.

December 7, 2016

Ode to the Muff

by Heidi Brevik-Zender, guest contributor

As the calendar pages flip from November to December and we feel the weather grow increasingly chilly, many of us are probably reaching for the comforting warmth of winter accessories, those wooly hats, cozy gloves, and lined boots that shield our extremities from frosty winter climes. Even in (normally) balmy Southern California where I live, the mountains that I see from my window are capped with white snow, so scarves and gloves have been welcome additions to my outfits as I wrap up to ward off the early morning chill.

As fashion periodicals, mass-circulating advertisements, and historical garment collections from the 1800s show us, hats, gloves, and scarves were also ubiquitous clothing items in 19th-century French wardrobes. However, one common frost-fighting object from this bygone era that has *not* remained a staple for us today is the muff, a cylinder-shaped accessory, typically made of fur or other warm materials, into which hands could be inserted for protection from the elements. If muffs have largely fallen out of fashion today, popping up sporadically in vintage clothing shops, forgotten at the backs of relatives’ closets, or making only the odd appearance on the haute-couture runway, in past centuries they were much more pervasive, serving not only as functional protective clothing items but also as eye-catching decorative statement pieces. Take, for instance, this exquisite muff from the early 19th century, which is lined in fur and overlaid with striking crimson feathers.

For the 19th century dandy Octave Uzanne, muffs were subjects worthy of a book. A dandy luxury book producer and bric-a-brac-o-maniac, like his fin-de-siècle collector friend Robert de Montesquiou, Uzanne was a great admirer of beautiful tomes and ladies’ accessories alike.

For the 19th century dandy Octave Uzanne, muffs were subjects worthy of a book. A dandy luxury book producer and bric-a-brac-o-maniac, like his fin-de-siècle collector friend Robert de Montesquiou, Uzanne was a great admirer of beautiful tomes and ladies’ accessories alike.

In this elegantly presented volume Uzanne makes clear that the muff is far more than a mere hand-warmer. Fancying himself something of a muff historian, he traces an early example to Renaissance Italy, observing that in Venice, “celebrated courtesans and noble ladies at that time carried Muffs, which served for niches to minuscular dogs.” The conduit-like accessories could also be used to pass secret notes between lovers, prompting one writer to define the muff as “A letter-box, lined with white satin.”

According to Uzanne, muffs were worn by men as well as women, and often for similar reasons of coquetry. He notes “people used Muffs in winter just as much for elegance as for need” and quotes a contemporary observer who wrote “to-day (1768) men carry small Muffs lined with down, and trimmed with black or grey satin.” To meet the demand for muffs there were designated boutiques, such as this one pictured in Diderot’s famous  18th-century Encyclopedia, where consumers could purchase muffs and store them during the off-season. (One advantage to this system was that shop workers would de-louse the furry tubes, handing them over in fall, freshly bug-free, to their stylish wearers.)

18th-century Encyclopedia, where consumers could purchase muffs and store them during the off-season. (One advantage to this system was that shop workers would de-louse the furry tubes, handing them over in fall, freshly bug-free, to their stylish wearers.)

There was also a dark side to muffs, Uzanne points out, noting that the accessory could call up tragedy and suffering. He describes a particularly sad muff episode from Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème (1851), a series of sketches about impoverished bohemian artists living in the Latin Quarter that Giacomo Puccini reworked into the 1896 opera La Bohème. (Readers today may be more familiar with the hit Broadway musical up date of Puccini’s opera, RENT, or the movie version of the musical from 2005.) Reading Murger’s original text, Uzanne is brought to tears when the female protagonist, dying of consumption, asks only for a muff for her frozen hands, one that she hopes to wear the next day on a walk with her lover. Tragically, though, she soon dies, expiring while still clutching her new muff. (Not surprisingly there is no muff mentioned in “Light My Candle,” the corresponding song in RENT; instead, it is replaced in the musical with a reference to the handcuffs that Mimi, an exotic dancer, wears during performances.)

date of Puccini’s opera, RENT, or the movie version of the musical from 2005.) Reading Murger’s original text, Uzanne is brought to tears when the female protagonist, dying of consumption, asks only for a muff for her frozen hands, one that she hopes to wear the next day on a walk with her lover. Tragically, though, she soon dies, expiring while still clutching her new muff. (Not surprisingly there is no muff mentioned in “Light My Candle,” the corresponding song in RENT; instead, it is replaced in the musical with a reference to the handcuffs that Mimi, an exotic dancer, wears during performances.)

This sensitive tale notwithstanding, it is the luxurious, delightfully frivolous, and sensual characteristics of the muff that ultimately draw Uzanne to it. “The Muff! The very name has something about it delicate, downy, and voluptuous,” he exclaims. In a passage moving from nostalgia to a barely concealed naughtiness that seems primed for Freudian analysis, he then muses, “In childhood, we delight to play with the large maternal Muff, to pass our hands over it the wrong way to excite the electricity of the long hair, to plunge our faces in the pungent heady odor of its down, and to make use of this furred sack in inconceivable tricks, in playing at hide-and-seek with small objects, or in burying therein the family cat, who becomes lazy in its warmth.”

From lap-dog holder to love-note carrier to trigger for dubious memories of Mommy, it would seem that, for Uzanne, warming hands was the least compelling of the muff’s myriad functions.

Heidi Brevik-Zender is Associate Professor of French and Comparative Literature at University of California, Riverside. She is the author of Fashioning Spaces: Mode and Modernity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Paris.

For instance, the 2001 Fall Couture collection by Parisian fashion house Balmain featured a sumptuous gray muff-and-hat combo.

For more on Uzanne and other Parisian luxury book producers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries see Willa Z. Silverman’s fascinating book, The New Bibliopolis: French Book Collectors and the Culture of Print, 1880-1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008).

For more on the fashion accessory see Susan Hiner’s excellent Accessories to Modernity: Fashion and the Feminine in Nineteenth-Century France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010).

Puccini renders this scene in the memorable aria “Che gelida manina” (“What a cold little hand”).

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column on nineteenth-century material culture, edited by Rachel Mesch. You can find my other posts here!

Prince Eugene of Savoy: The Sun King’s Shadow

Prince Eugene of Savoy

By Robert Krebs (Guest Contributor)

In 1701 at Carpi, he was there. Later that year, he appeared at Chiari. As 1701 rolled over into 1702, he could be found at Cremona. Two years later in 1704, he was seen once more at Blenheim—with a friend, the duke of Marlborough, this time. He popped up at Mirandola, Cassano, Turin, Toulon, Susa, Oudenarde, Lille, and Malplaquet too. Admittedly, the list of locations is beginning to sound like a long-lost verse from the Hank Snow song “I’ve Been Everywhere.”

But it’s true. On battlefields across Europe, Prince Eugene of Savoy was there. So were the armies of Louis XIV. In nearly half a century of fighting, French land units had suffered no major battlefield defeats. Success bordered on hegemony. Victories could be tallied in the War of Devolution, the Dutch War, the War of the Reunions, and the Nine Years War. However, with the War of the Spanish Succession, the Sun King’s military brilliance was—if only briefly—dimmed. Eclipsing Louis was none other than Prince Eugene.

Prince Eugene of Savory was a military savant, at least according to Napoleon. Only forty years old at the breakout of the War of the Spanish Succession, Prince Eugene of Savoy commanded all armies for the Holy Roman Empire. His success against French armies frustrated Louis, who wrote to one of his generals “Your obey the rules of the art of war, Prince Eugene doesn’t give a fig for them.” Prince Eugene of Savoy also didn’t “give a fig” for learning how to spell his name in German. He never thought of himself as either Austrian or German, for he was French at heart.

The Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy at Blenheim (Robert Alexander Hillingford).

How did a man who spoke and wrote exclusively in French come to fight for the Holy Roman Empire? The answer involves a cardinal, a poisoning, and a rejected petition. Prince Eugene grew up in the French court, if on its periphery. His mother Olympia Mancini, the countess of Soissons, was a niece of Cardinal Mazarin and an early mistress of Louis XIV. If love and lineage were kind to Prince Eugene, genetics were quite cruel. Physically frail, the jaundiced and unattractive Eugene was quickly shoved towards the clergy. Despite this, Eugene maintained an interest in war; he studied military strategy and learned to handle weapons and ride horses.

Like every teenage son, Prince Eugene also had his mother to blame for his unfortunate scenario. During the Affair of the Poisons, evidence emerged suggesting that she had poisoned her husband and was involved in a plot to poison Louise de la Vallière, then the first mistress of Louis XIV. Strongly convinced of her guilt, yet aware of his intimate connection to Olympia, Louis gave her the opportunity to face trial or leave France. She opted for the latter. Thanks, Mom.

To Prince Eugene, his name fell into disrepute. And so, when he petitioned Louis XIV for a position in the army, he was rebuffed. Louis remarked that, “nobody ever ventured to stare me in the face so insolently, like an angry sparrow hawk.” Incensed, Prince Eugene of Savoy left, offering his allegiance to Leopold I and the Holy Roman Empire. The rest is history.

Bibliography

Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667-1714. Longman, 1999.

Mollenauer, Lynn Wood. “The Politics of Poison: Courtiers and Criminals in the Affair of the Poisons, 1679-1682.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1999.

Wernick, Robert. “The Little Prince Who Grew Up to Haunt Louis XIV.” Smithsonian, January 1985, pp. 54-63.

Robert Krebs is a senior at Vanderbilt University studying Public Policy, French, and Mathematics. He is most interested in the quantitative study of legislative behavior, but also devotes time to playing and arguing about hockey.

Robert Krebs is a senior at Vanderbilt University studying Public Policy, French, and Mathematics. He is most interested in the quantitative study of legislative behavior, but also devotes time to playing and arguing about hockey.

December 6, 2016

A Broken Fairytale: Inside the Scandalous Royal Marriage of Philippe of Orleans and Henriette of England

Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

By Lindsay Williams (Guest Contributor)

Love triangles. Forbidden love. Deception. Money. Murder. You would expect to find these in TV dramas like “Scandal” or “House of Cards.” But this was the reality of the marriage between Philippe I, brother to Louis XIV, and his first wife, Henriette Anne. Their tumultuous marriage irrevocably altered the relationship between Philippe and his brother, the Sun King, and scandalized the court.

Contemporaries at court, especially the court historian Saint-Simone, solidified Philippe’s reputation for silliness and effeminacy. He often dressed like a woman, and preferred men. What is frequently overlooked, however, was that Philippe was an accomplished soldier. His service in the Franco-Dutch war was vital to French success.

Henriette Anne of England

Philippe’s first wife, styled Madame, was Henriette Anne of England, his cousin who had taken refuge in France as a result of the civil wars in England and the death of her father. Although she was thought too skinny to be considered a great beauty, she was charming, flirtatious, vivacious. She played a role in politics with her close relationship with Louis, and even served as a diplomat in negotiations with Charles II, her brother.

The Beginning

Prior to the marriage, Philippe appeared quite devoted to Henriette. He seemed very much in love and expressed his desire to marry quickly. However, this was likely all an act. He had no great affection for Henriette prior to the death of his uncle, which left him an inheritance to be collected when he married. In fact, it is unlikely Philippe was ever in love with Henriette. Philippe had many affairs with different men, but the true love of his life was probably the Chevalier de Lorraine, who he met during his service in the War of Devolution.

Chevalier de Lorraine, Philippe’s lover and suspected killer of Henriette Anne

The Uncrowned Queen

Philippe was not the only one to have affairs. Henriette took several lovers, which enraged Philippe’s jealous nature. Two of her relationships in particular were humiliating to Philippe and devastating to their marriage. When Philippe and Henriette went to court, she and Louis had at the very least an emotional affair, and a suspected physical affair. They made no attempts to hide it, making Philippe the laughingstock of the court. In addition, she seduced Philippe’s lover the comte de Guiche, once again humiliating the prince. Their marriage at this point was broken beyond repair. But despite this, they continued to be the life of the party, holding court and having celebrations regularly.

How to Get Away with Murder

Intrigue, gossip, and scandal did not only follow the unhappy couple in life. Although Henriette was always sickly, and more so at the end of her life, she was thought to have been poisoned. Although some believed Philippe was involved, the most popular theory at the time was that the Chevalier de Lorraine had organized the murder without the involvement of Monsieur.

Bibliography

Barker, Nancy Nichols. Brother to the Sun King: Philippe, Duke of Orleans. Johns Hopkins UP, 1989.

Barker, Nancy Nichols. “Philippe d’Orleans, Frère Unique du Roi: Founder of the Family Fortune.” French Historical Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, Fall 1983, pp. 145-71.

Cartwright, Julia. Madame: A Life of Henrietta, Daughter of Charles I and Duchess of Orleans. Seeley and Co., 1894.

Lindsay Williams is a sophomore at Vanderbilt University. She is working towards a major in Environmental Sociology and a minor in French and American Politics. She is an officer of several student organizations, including the Vanderbilt Political Review, Vanderbilt Splash!, and the Lambda Iota chapter of Zeta Tau Alpha.

December 5, 2016

Dinosaur Tracks Venerated as Footprints of Mythic Beast in China

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

In the Jurassic era, massive 70-ton Sauropod dinosaurs tromped around what is now China, leaving deep tracks in mud that became stone. About 150 million years later, a conspicuous Sauropod trackway was discovered by villagers in Tongsi, who believed that the fossil footprints were made by a legendary beast in Chinese folklore.

The striking set of 18 sauropod dinosaur footprints are embedded in rock at Luoguan Mountain (near Zigong City, Fushon County, China). They were “discovered” by Chinese paleontologists in 2009, but it turns out the tracksite had been revered by local people for centuries. Following the ancient trail was thought to bring good fortune.

According to the local oral traditions, the huge oval tracks, about 8 inches across and 12.5 inches long, were made by Divine Lucky Rhinoceros. In the story, the venerable Rhinoceros trudged up Luoguan Mountain to gather Lingzhi — “mushrooms of immortality” — a rare red fungus that grows on very old maple tree stumps. Reishi mushrooms, Ganoderma lingzhi, are still believed to have miraculous medicinal powers. As the great Rhinoceros trekked up the slope seeking mushrooms, he left a trail sunk in stone.

We reported the oral tradition associated with the Sauropod tracks in “The Folklore of Dinosaur Trackways in China: Impact on Paleontology,” by L. Xing, A. Mayor, Y. Chen, J. Harris, and M. Burns, in the journal of trace fossils, Ichnos 18 (2011): 213–20.

What is so interesting about this tale is that there are no wild rhinoceroses in China. In antiquity, however, three different types of Asian rhinoceroses did roam China (along with elephants). Rhinos were depicted realistically in Chinese art as early as 1000 BC. Rhinoceroses were hunted extensively. Killing a rhinoceros was believed to ensure rain. Tough rhino hide was fashioned into armor for warriors. Rhinos were also slaughtered for their horns, prized for medicine and for drinking cups, believed to detect poison. Rhinoceros horn drinking cups were often carved in the distinctive shape of reishi mushrooms, recalling the Lucky Rhino’s search for mushrooms in the Tongsi local tale.

But the unlucky rhinoceros of China was hunted to extinction during the Song Dynasty, in the 13th century. The sad fate of the Chinese rhinoceros gives us an idea of the great antiquity of the local oral tradition about the Divine Lucky Rhinoceros tracks in stone. Venerated yet hunted into extinction, the Chinese rhinoceros only survives today in age-old folk memories of a massive wild beast that disappeared 800 years ago.

Adrienne Mayor, a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times (2011), Fossil Legends of the First Americans (2005), The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons (2014).