Holly Tucker's Blog, page 2

March 20, 2017

Risk Insurance in the Eighteenth Century

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Travelers to distant lands have always known that risk is an inevitable part of the adventure. And from ancient times they invented ways to mitigate that risk. Medieval English guilds established funds to provide for their members in the event of accident when they were abroad. Fifteenth-century pilgrims would ensure themselves against captivity. For a certain payment, the insurer would agree to ransom the traveler should he be captured by pirates or Arabs.

As travel expanded, individual traveler’s insurance took on the form of a bet on their own survival – a broker would take a specific amount and agree to pay it back with substantial interest if the traveler returned. The risks of travel were so high that it was usually assumed impossible to purchase insurance that would pay out to someone else if the traveler did not come home.

As travel expanded, individual traveler’s insurance took on the form of a bet on their own survival – a broker would take a specific amount and agree to pay it back with substantial interest if the traveler returned. The risks of travel were so high that it was usually assumed impossible to purchase insurance that would pay out to someone else if the traveler did not come home.

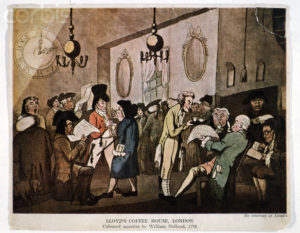

By the end of the seventeenth century in England, something closer to a modern

Edward Lloyd’s coffee house, 1798

insurance system was developing. After the great fire in London in 1680, fire insurance became available. The Royal Exchange, incorporated in 1720, started to offer life insurance. Lloyd’s coffee house was a place where seafaring captains could share shipping news and negotiate private contracts to cover the risk of shipwreck or violent conflict encountered on their trade routes. Maritime insurance expanded. Captains were able to insure their own lives along with the life of their ships.

But insurance still bore a close resemblance to gambling. In a coffee house or a bank, people could buy “insurance” against almost anything, including the adultery of a spouse or treachery of a friend. Many insurers were simply speculators and gamblers. Insurance underwriters would issue policies on the outcome of battles or sensational trials or the sequence of the king’s mistresses. In almost every country except England, life insurance was viewed simply as a wager, and was illegal.

It was not easy, either, to determine the premiums for life insurance in eighteenth-century England. Mortality statistics were available but often disputed. Life expectancy was highly variable but generally low. With an increasing number of ships travelling the globe, though, and reliable records of shipwrecks, it was possible to make risk estimates for ordinary travelers going to different parts of the world. Insuring one’s life on a trip to France or Spain was much cheaper than for a voyage to the Bahamas. If you wanted to be insured on a trip to North Carolina it was even more expensive.

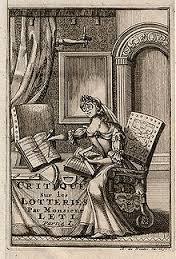

The uneasy association of life insurance, gambling, and travel can be seen in early accounts of cheating and fraud. Newspapers caricatured women obsessed with gaming or winning the lottery, who busied themselves with mathematical calculations that would enhance their chances. Insurance fraud perpetuated by traveling women seems to have been particularly feared. Life insurance was not simply for the patient wife left behind while her husband traveled the globe. The images of gambling women were echoed in stories of women who traveled to distant lands, made calculated marriages, bought expensive life insurance policies on their husbands, then moved to another location to repeat the scenario after their husbands had died.

In order for insurance to really take hold as an institution, it was necessary for it to start being regarded by middle-class wage earners as an expenditure that was both virtuous and the personally responsible thing to do. It also had to be understood not as a gamble but as a prudent, risk-averse choice. By the nineteenth century, churches and banks both worked to persuade citizens of their responsibilities to their families. Even mathematicians, who contributed to the development of actuarial tables, were enlisted to sing the virtues of insurance. In his treatise on probability, Pierre Laplace described insurance as “advantageous to morals, in favoring the gentlest tendencies of nature.”

In order for insurance to really take hold as an institution, it was necessary for it to start being regarded by middle-class wage earners as an expenditure that was both virtuous and the personally responsible thing to do. It also had to be understood not as a gamble but as a prudent, risk-averse choice. By the nineteenth century, churches and banks both worked to persuade citizens of their responsibilities to their families. Even mathematicians, who contributed to the development of actuarial tables, were enlisted to sing the virtues of insurance. In his treatise on probability, Pierre Laplace described insurance as “advantageous to morals, in favoring the gentlest tendencies of nature.”

For further reading: Lorraine Daston, Classical Probability in the Enlightenment (1988); John Francis, Annals, Anecdotes, and Legends: A Chronicle of Life Assurance (1853).

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

The post Risk Insurance in the Eighteenth Century appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 17, 2017

Five for Friday: Imogen Robertson

Interview with Imogen Robertson

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

I knew I wanted a change from the Crowther and Westerman Eighteenth Century crime series I write, and while I was thinking what I might do I came across my Grandmother’s old photo albums. She was born in the 1890s and travelled alone across Europe in the years before the first World War. When she travelled, she carried a sketchbook and looking at her watercolours I began to think about a young, quite inexperienced middle-class girl travelling to Paris to study art and what she might face there and so Maud, my protagonist, was born. Around the same time I stumbled across an article about the floods in Paris of early 1910 when the Seine seemed to revenge itself on the modernity of the city, travelling up the new métro tunnels and sewers to devastate areas far from the river banks. The ground beneath the feet of the Parisians became unstable. I couldn’t resist that setting for a novel of intrigue and betrayal.

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

I started with a lot of reading, browsing through the newspapers for eyewitness accounts and telling details, looking for the things I didn’t know I didn’t know! I found all sorts of leads, odds and ends which became important for the novel, a Parisian charity for impoverished English and American women appealing for funds for example. Libraries can’t tell you everything though. I was lucky enough to spend time with an artist trained in the same way Maud would have been, and listening to her talk about art as well as just being in her studio was a huge help. I also got to handle some very lovely diamonds! And of course I went to Paris. I met an American writer who lives there, David Downie, and he and his wife took me on a wonderful tour of secret corners perfect for the novel which I would never have found on my own. In terms of organisation, I write up my research longhand – seems to sink in better that way – and gather bundles of images on the computer. It’s never as well organised as I would like though.

Marie Bashkirtseff – In the Studio

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

I always struggle to leave the research alone and get writing! Hanging around in libraries or with artists and diamond dealers is too much fun. One thing I’ve learnt though is that every novel has its own unique set of problems and there is no way to avoid bumping up against them. Sometimes it’s the crucial detail you need isn’t there in the research, sometimes it’s that a character changes on the page and suddenly your plot doesn’t work any more. It drives me mad, but I think if I found it easy now – research, writing or structure, I’d worry I wasn’t working hard enough.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

Ah, well in this case it was quite dramatic, I left about a third of the novel behind! I had a modern parallel narrative on the go in my first to third drafts, a young woman discovering the story of Maud and the mysteries of her time in Paris. I loved her, but the push and pull of moving between times was simply not working in this novel. After talking it over with my editor, I realised I had to keep the whole story in the Belle Époque, and cut about thirty thousand words. It was a frightening afternoon, but after that the rewriting was a pleasure and the story of Maud and her struggles had the room it needed to deepen and grow.

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

I’m tagging M J Carter who is the author of the Blake and Avery adventure stories as well as being a distinguished historian. Her writing is vivid and pacy, her understanding of her characters subtle and acute and her fast-paced plotting makes for a really engaging and satisfying read.

Imogen Robertson was born in Darlington and studied German and Russian at Caius College, Cambridge. After some years directing TV, film and radio she became a full time writer on winning the Telegraph’s ‘First thousand words of a novel’ competition in 2007. Since then she has written five novels in the Westerman and Crowther crime series which is set in the late 18th century, beginning with ‘Instruments of Darkness’ in 2009. The latest volume in the series, ‘Theft of Life’, is set in London against the background of the transatlantic slave trade. She has also written ‘The Paris Winter’ – a novel of betrayal and revenge set in the late Belle Époque. She has been shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger three times and is currently Chair of the Historical Writers’ Association.

Imogen Robertson was born in Darlington and studied German and Russian at Caius College, Cambridge. After some years directing TV, film and radio she became a full time writer on winning the Telegraph’s ‘First thousand words of a novel’ competition in 2007. Since then she has written five novels in the Westerman and Crowther crime series which is set in the late 18th century, beginning with ‘Instruments of Darkness’ in 2009. The latest volume in the series, ‘Theft of Life’, is set in London against the background of the transatlantic slave trade. She has also written ‘The Paris Winter’ – a novel of betrayal and revenge set in the late Belle Époque. She has been shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger three times and is currently Chair of the Historical Writers’ Association.

Missed our previous Five for Friday? Read last week’s interview with Ed O’Loughlin. Want to binge read our interviews with fantastic authors? Check out our interviews with Sophia Tobin, Georgia Hunter, Anna Mazola, Essie Fox, Ami McKay, and Eva Stachniak.

The post Five for Friday: Imogen Robertson appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 16, 2017

Medicine in the Marketplace

By J.C. McKeown (Guest Contributor)

A doctor, like a savior god, should be on equal terms with slaves, with the poor, with the rich, with kings, and he should help everyone like a brother. For we are all brothers. He should not hate anyone, nor harbor spite in his mind, nor foster self-importance.

Asclepius with his sacred snake, looking up at him like a faithful dog.

Leaving aside the possible difficulty in avoiding self-importance while acting like a god, does this noble view of the medical profession really reflect the attitudes and convictions of doctors in ancient Greece? Even in our own enlightened times, the quality of medical treatment provided often depends on the patient’s ability to pay and outrageous price hikes for essential drugs are still legal, so it is perhaps not overly surprising to find that similar market forces affected medicine in antiquity.

Vested interests, we are told, reared their head right from the start. Asclepius, the god of medicine himself, was deified in recognition of his medical skill, but only after he been killed by the god of the Underworld for reducing the supply of dead people. There was a hostile tradition that Hippocrates, revered as the founder of Western medicine, stooped to handicapping potential competition by burning a temple which stored medical case-studies.

Cutting out the competition was inevitably important, given that there was no central authority regulating the profession and endorsing a doctor’s credentials:

To have himself recognized as a qualified practitioner, a doctor does not need to give an actual demonstration of his skill, even though medicine is such an eminently practical discipline – all he has to do is claim to have received his training in Alexandria

Charlatans thrived in such an unmonitored environment. How else might one account for the low expectations aspired to one of the leading physicians of the early Hellenistic period?:

Ideally, a doctor should be outstanding in his medical expertise, and also a person of excellent character. If one of these qualities is missing, it is better that he should be a good man with no learning rather than a thoroughgoing expert, but unscrupulous and immoral. The decency that accompanies good character seems to compensate for lack of knowledge, whereas moral flaws may taint and corrupt medical skill, however great.

The loudest and brashest of all such quacks, if we may believe his opponents, was undoubtedly Thessalus of Tralles, who flourished in the mid-first century AD:

During the rule of Nero, Thessalus rose to fame in the medical profession, sweeping aside all received medical wisdom and denouncing all doctors from every epoch with a sort of frenzy. You can get a clear idea of his sense of judgment and his attitude just by looking at his tomb on the Appian Way, where the inscription refers to him by the Greek term iatronikes (“The Conqueror of Doctors”). No actor or charioteer went out in public accompanied by a larger throng.

One last financial consideration may perhaps give some comfort to today’s young medical practitioners, heavily burdened by debts accumulated through long years of study. The Hippocratic Oath required students “to share their livelihood with their teachers and give them a tithe of what they possess, should they be in need”. This provision does not appear in modern versions of the oath.

J.C. McKeown is professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities (2010) and A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities (2013), also published by Oxford University Press

J.C. McKeown is professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities (2010) and A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities (2013), also published by Oxford University Press

Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 28 (1978) 225, part of a damaged inscription from the Sarapion monument in the temple of Asclepius on the Athenian acropolis.

Celsus On Medicine Preface 2.

Diodorus Siculus The Library 4.71.

Soranus Life of Hippocrates 4.

Ammianus Marcellinus History of Rome 22.16.

Erasistratus frg. 31.

Pliny Natural History 29.9.

The post Medicine in the Marketplace appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 14, 2017

Joe Sprinz and the Speeding Baseball

by Jack El-Hai (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

For a certain group of enthusiasts — of which I am one — these are the weeks that bring hope at the end of the long, cold winter. Down south, in states climatologically blessed, uniformed players are throwing balls, swinging bats, and loosening muscles. Of all the visions that most strongly signal the return of baseball, my favorite is the sight of a catcher hurling away his facemask to circle under a high pop fly and make the catch.

But the catcher does not always make the catch. Or the falling ball does not always behave as we expect it to. What happened to catcher Joe Sprinz when he tried to catch a plummeting ball in 1939 is unparalleled in baseball lore.

A publicity stunt

Sprinz, whose best years were by then behind him, had seen major league action as a career .170 hitter between 1930 and 1933 with the St. Louis Cardinals and the Cleveland ballclub. In 1939, the veteran was on the way down, playing in the Pacific Coast League with the minor-league San Francisco Seals.

To mark the centennial of the invention of baseball and the celebration of Baseball Day at the Golden Gate Exposition, the Seals came up with a publicity stunt. On August 3 they floated a Goodyear blimp 800 feet over Seals Stadium, from which blimp captain A. J. Sewell would drop some baseballs. It was Sprinz’s job to stand beneath, glove in hand, to wait for these tiniest of white specks to enlarge into balls falling at a ferocious speed, and to make the catch. If he succeeded, he would set a new record for catching a baseball dropped from the greatest height.

This wasn’t a completely original idea. Just three months earlier, Philadelphia Phillies catcher Dave Coble had caught a ball dropped 521 feet from the tower of Philadelphia’s city hall. Other ballplayers had attempted similar stunts.

Falling at 170 MPH

But the attempt in San Francisco was the most ambitious. The first four balls dropped from the blimp over Seals Stadium fell far from Sprinz. He had a chance to catch the fifth, though. He settled under it, and the ball shot into his mitt. The ball was moving at something like 170 miles per hour, however — a velocity with which Sprinz had no previous experience. The ball and mitt crushed the ballplayer’s face, injuring his nose, causing a compound jaw fracture, smashing eight teeth, and cutting both lips. The impact also knocked Sprinz senseless. “He fell forward and writhed in agony as his teammates rushed toward him,” a reporter with the San Francisco Examiner observed.

It was Sprinz’s thirty-seventh birthday. And according to an account filed by the Associated Press, he dropped the ball.

Sprinz recovered. He retired from baseball three years later and managed little leagues in San Francisco. He died in 1977 at the age of 75.

Baseball is about dropping balls as well as catching them, swinging through pitches as well as making contact with them. Let the season begin.

Further reading:

Jacobs, Martin and Jack McGuire. San Francisco Seals. Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

Phillips, John. “Take Me Out to the Hospital: Baseball’s Goofiest Injuries.” The Washington Post, September 19, 1993; p. C5.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

The post Joe Sprinz and the Speeding Baseball appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

The Strange Death of a Cautious Courtesan

By Aaron Freundschuh (Guest Contributor)

Until the night of her murder in a lavish apartment just off the Champs-Elysées, Madame Régine de Montille had taken pains to avoid the demise of her less fortunate colleagues and friends in the demimonde. As she was well aware, the 1870s and 1880s saw prostitutes murdered with jarring frequency in Paris, capital of the nineteenth-century sex trade. Unlike the era’s famous courtesans, who included luminaries such as Sarah Bernhardt and Marguerite Durand, Madame de Montille steadfastly avoided the public eye, thereby sparing herself the burdens of risk and resentment.

Scorn was for prostitutes of all stations a matter of course, likewise the scourge of caricature that rendered the sex worker a central figure of contemporary fiction and a durable muse of modernist art. On a more quotidian basis, their male clients presented the single greatest menace: they carried debilitating diseases and could turn violent or become possessive—or just refuse to pay for a pass, safe in the knowledge that sex workers had no recourse to the law. In fact, a call to the police was a courtesan’s act of last resort, since the officers of the vice squad were notoriously abusive, arbitrary, and broadly exploitative in their approach. For courtesans who ran afoul of a powerful client or crooked vice cop, the whiff of public scandal could lead to summary deportation—robust demand for foreign and “exotic” prostitutes encouraged trafficking through French ports—or imprisonment. Newspaper editors knew that social ostracism made good copy; the press gleefully traced the descent of a kept woman into addiction, impoverishment, and an early grave.

Madame de Montille: a high class prostitute

Madame de Montille (née Marie Regnault) was nigh on 40 when she died, an uncommonly prosperous career having whisked her from provincial poverty to the high life of the capital’s tony districts. In two decades she amassed the kind of wealth most Frenchmen could never attain, and she did it without so much as a brush with the law. Granted, the vice squad snooped on her for a time during the 1870s. They opened up a file and kept irregular tabs. Yet administrative knowledge of her, stored in the “secret archives” of the Paris police prefecture, remained scant. This was because she observed the two most important rules in high-class prostitution: find powerful protectors, and be discreet about it. By the end of her career Montille’s protectors issued from the upper echelons of the military and the business world, though fate could just as easily have made them politicians, policemen, or impresarios. What mattered was power, specifically an influence on the police bureaucracy, which oversaw the enormous shadow economy in paid sex (prostitution was technically illegal and at the same time loosely regulated).

Madame de Montille had a sister who was also a demimondaine. Together, the two women pooled risk and resources from the moment they departed their Burgundy hometown. They installed themselves near the Gare Saint-Lazare, a newly constructed area often depicted in Impressionist painting. They tricked in cozy, high-end brothels around the Grands Boulevards. Madame de Montille made shrewd purchases of Salon art and expensive jewelry, ensuring the long-term interest of elite clients who were willing to pay a premium for cultured companions. She acquired an expansive collection of literary works. Without a doubt, her crowning achievement was to ensconce herself in the rue Montaigne, an elite enclave in the eighth arrondissement. (Her apartment had been previously occupied by an Admiral of the French Navy.) In her spare time she enjoyed embroidery, a lifelong passion that suited her retiring disposition. She was well-appreciated by an exclusive group of clients; she had no known addictions, no debt, and no enemies.

An unfortunate encounter

It was therefore difficult to conceive that Madame de Montille could commit the gross error in judgment that precipitated her death on March 16, 1887. That evening, she admitted her killer into the apartment and, according to the coroner’s report, had intercourse with him. Her body was discovered, along with that of her live-in servant and the latter’s young daughter, shortly before noon the next day.

The murders in the rue Montaigne were all the more puzzling to police given Madame de Montille’s obsessiveness about matters of security, about which much was said. She had lately installed extra locks on her doors, and she kept almost all of her jewelry, cash and investments—a collection worth a considerable fortune—in an impenetrable safe in her boudoir. The faithfulness of her personal staff was never in question. For many years she had employed the same private laundress; she lodged her private chef in a small apartment upstairs. Annette, her live-in servant, had been a childhood friend. The concierge and his wife, who in fact lived downstairs, had long been complicit in her business.

A piece in the puzzle of a dramatic investigation

Aside from the material clues found at the crime scene, there were nonetheless hints of a personal crisis. The tone of Madame de Montille’s recent diary writings was consonant with depression and a growing sense of helplessness. There had been a broken love story, a newfound recklessness. According to the concierge’s wife, there were new men—that is, not the usual protectors—calling on her of late. One of these, a smallish fellow with brown hair, appeared suspiciously outclassed.

Aside from the material clues found at the crime scene, there were nonetheless hints of a personal crisis. The tone of Madame de Montille’s recent diary writings was consonant with depression and a growing sense of helplessness. There had been a broken love story, a newfound recklessness. According to the concierge’s wife, there were new men—that is, not the usual protectors—calling on her of late. One of these, a smallish fellow with brown hair, appeared suspiciously outclassed.

When the Paris police fanned out in search of this man they couldn’t have had the faintest idea that they were embarking on the first global murder investigation. Within weeks the prosecutor’s thick dossier would contain evidence from Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, Afghanistan, India, Italy, Monte Carlo, and New York City—all the requisite pieces for a courtroom drama that no one would soon forget.

Aaron Freundschuh’s recently published book is, The Courtesan and the Gigolo: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford University Press, 2017).

The post The Strange Death of a Cautious Courtesan appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 13, 2017

The Chameleon in the Classroom

By Helen King (Monthly Contributor)

This is a story of illness and magic from the fourth century CE. Even though Constantine had converted the Roman Empire to Christianity, paganism didn’t just lie down and die. One of the most famous pagan intellectuals was Libanius, a distinguished orator who taught rhetoric to famous Christian figures such as Basil the Great and John Chrystostom. Born in Antioch in Syria, Libanius’ life spanned the century. He returned to his home city in 354 to teach, and remained there until he died.

This is a story of illness and magic from the fourth century CE. Even though Constantine had converted the Roman Empire to Christianity, paganism didn’t just lie down and die. One of the most famous pagan intellectuals was Libanius, a distinguished orator who taught rhetoric to famous Christian figures such as Basil the Great and John Chrystostom. Born in Antioch in Syria, Libanius’ life spanned the century. He returned to his home city in 354 to teach, and remained there until he died.

He wrote an account of his own life (although, as ever, it’s difficult to say how much of this is self-promotion), as well as many letters: a startling 1544 of these still survive. Libanius suffered from severe headaches for much of his life, and he traced these back to a lightning strike when he was 20. He described this as follows:

I was standing by my teacher’s chair engrossed in the Acharnians of Aristophanes, when the sun was hidden by such a pall of cloud that you could hardly tell the difference then between day and night. The heavens resounded with a mighty crash and a thunderbolt hurtled down, blinding my eyes with its flash and stunning my head with its roar. My first thought was that I had suffered no permanent ill-effect and that the shock would soon settle. However, after I had reached home and was at the lunch table, I seemed again to sense that crash and the thunderbolt hurtling past the house. I broke out into a sweat of fear, and leapt up from the table to the refuge of my bed (Oration 1, ch.9: Loeb Classical Library translation)

He decided not to mention to any physician what had happened; he wasn’t keen on ‘being dragged from my usual routine to take medicine or undergo professional treatment’. Later, he decided that this had been the wrong decision, as his reluctance had meant that the fear took root more deeply.

In his 50s, he suffered from both migraine and gout, and developed a fear of crowds with dizziness and difficulty in breathing (Oration 1, ch.141). He continued to trace his migraines back to the thunderbolt incident. After a 16-year remission, which he attributed to the healing god Asclepius, he had a particularly bad attack in his early 70s, in 386, and found he was unable to read, write or speak in class (Oration 1, ch.243). This reminds us of the second-century CE rhetor, Aelius Aristides, who like Libanius wrote about his own experiences as someone whose career depended on public speaking but who was unable to do this during acute episodes of illness. Aelius Aristides similarly found that his time at the sanctuary of the healing god Asclepius helped him to cope. For example, in a dream the god suggested having a choir who could start to sing at points when Aristides’ voice was weakening.

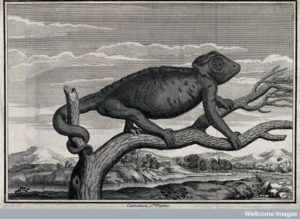

Libanius found a rather different way of coping. He experienced a disturbing dream about murder which he saw as evidence that magic was being used against him by a rival. Soon afterwards, a (very) dead chameleon was found in his classroom, with its head pushed between its back legs, and one of its front legs over its mouth, as if to silence it (Oration 1, ch.141). The other front leg was missing. The wrongly-positioned head may have suggested to him that this was connected with his migraine, and the blockage of the mouth his difficulty speaking. The missing front leg may have recalled his gout, or perhaps the arm with which he would gesticulate while speaking in public.

A chameleon on a branch with landscape background. Etching.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Chameleons have long been considered as very strange animals. Pliny’s Natural History (8.51) describes them not only in terms of their capacity to change colour, but also as bloodless, their mouths always open as they are nourished by the air alone. Libanius was in any case convinced that his illness at this point was magical in origin, caused by a rival, and finding the chameleon confirmed his fears. However, because he found he felt better after this incident, he assumed this meant that those who were trying to harm him had eased off their magical practices. And that, in turn, made him feel even better!

Further reading

Bonner, C. ‘Witchcraft in the lecture room of Libanius’, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol.63 (1932), 34-44

Cribiore, R. Libanius the Sophist: Rhetoric, Reality, and Religion in the Fourth Century (Cornell University Press, 2013)

Norman, A.F. Antioch as a Centre of Hellenic Culture as Observed by Libanius (Liverpool University Press, 2000)

The post The Chameleon in the Classroom appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 8, 2017

Civilization in Every Pot

By Michael Garval (Regular Contributor)

It’s said that beloved French Renaissance king Henri IV promised his subjects la poule au pot, a modest “chicken in every pot.” By the end of the nineteenth century, the expansion of the French colonial empire, with its self-appointed “civilizing mission,” and French gastronomy’s concurrent rise to international preeminence, urged on a more grandiose vision. France now promised the world civilization in every pot.

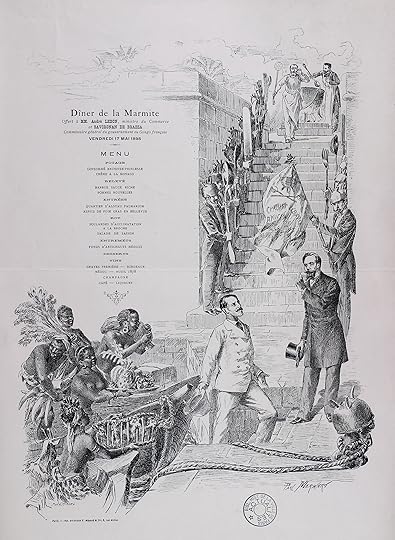

Paul Merwart, Banquet menu, May 17, 1895, Dîner de la Marmite, in honor of MM. André Lebon, Minister of Trade, and Savorgnan de Brazza, Governor General of the French Congo (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris)

This 1895 banquet menu honors Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, governor general of the French Congo, territory he explored and claimed for France (it was drawn by Paul Merwart, an artist fond of exotic subjects, who would later become the official painter of both the French colonies and the French navy). Brazza disembarks in France, as boats representing Africa – with native women and raw ingredients – moor at the quai. He is greeted by the other featured guest, trade minister André Lebon, who points Brazza, and our gaze, up a staircase, lined by a sort of honor guard in civilian evening dress.

Detail, Paul Merwart, Banquet menu, May 17, 1895, Dîner de la Marmite, in honor of MM. André Lebon, Minister of Trade, and Savorgnan de Brazza, Governor General of the French Congo (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris)

Steep and massive, the stone staircase and embankments separate Africa below from France above. At top, at the pinnacle of frenchness, stands a giant pot, stirred by one chef as another summons guests. Brazza’s return is depicted as an ascent, from colonized lands to colonizer’s land, raw to cooked, ‘primitive’ to ‘civilized,’ with Africa as a foil for its presumed opposite. The viewer, like Brazza, is invited to step up for some French food. But what kind?

While La Marmite is the sponsoring organization’s name, the term, like its rough synonym le pot-au-feu, designates a French cooking vessel and its quasi-mythical contents – the primordial pot on the ancestral hearth, with boiled meats, vegetables, and stock, a simple, but emblematically French dish, like Henri IV’s poule au pot. Brazza, explorer of darkest Africa, had apparently come home to French comfort food. As in Roland Barthes’ example from his essay on “Steak and fries,” of General de Castries ordering french fries upon returning to France from Indochina, the pot-au-feu would function here as what Barthes calls “the alimentary sign of frenchness.”

Yet is this what Brazza would be served? The banquet menu, elevated literally and figuratively, like a commemorative, or sacred inscription, features such delicacies as Consommé Brunoise-Princesse, Barbue sauce Riche, Aspics de foie gras en Bellevue, not rustic fare from a steaming cauldron. And, despite African foodstuffs arriving, this is a thoroughly French dinner, from potage through café and liqueurs. Slippages occur, betwixt image and menu: home cooking yields to haute cuisine, exotic ingredients to classic French dishes.

Detail, Paul Merwart, Banquet menu, May 17, 1895, Dîner de la Marmite, in honor of MM. André Lebon, Minister of Trade, and Savorgnan de Brazza, Governor General of the French Congo (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris)

The honor guard that stands at attention, to welcome Brazza, brandishes a flag emblazoned with the amiable motto of the literary-artistic association La Marmite (“Coquit cibaria nutrit amicitias”), as well as giant forks, spoons, and knives in place of arms. On their heads, instead of helmets, they wear small pots that echo the illustration’s central marmite theme. Silverware seems mightier than the sword, and helmets get beaten into cookware.

With its studiously mock-martial air, the menu proffers a characteristically French vision of colonialism, less as a military or even commercial enterprise than as a more expansively cultural one. The culinary refinement awaiting Brazza betokens broader French “civilization,” exported across the globe in the age of the great Auguste Escoffier, whose kitchens trained and then sent several thousand chefs out into the world, and whose 1903 Guide Culinaire served as the bible of classic French cuisine for generations. It was a time when ambitious kitchens everywhere emulated the French model, with fancy menus worldwide flogging pretensions in oft-approximate culinary French.

But what of the Africans Brazza has left behind? How might they have welcomed him to their land, and what might have been steaming in their pots? A series of popular articles about Brazza’s travels in West Africa, that he published in the magazine Le Tour du Monde in 1887-1888, provides some sort of answer. Here we encounter the tired old cliché about natives cooking and eating European explorers.

In one article Brazza’s fellow explorers question his zeal for forging ever deeper into unknown territory. They draw a two-fold caricature, envisioning divergent scenarios for his fate. In the first part, natives dance round a giant pot, une marmite gigantesque, presumed full with “white meat”; in the second, he has become so thin that the same natives thumb their noses at such an unappetizing morsel.

Brazza however held more enlightened views. A committed pacifist and humanitarian, he opposed slavery and championed better living conditions for the indigenous population. He quickly dismisses the first caricature, noting that the natives in question did not eat Europeans, while confirming the general scarcity of food that would make a European thin should he spend some time with them.

Still, one wonders if the 1895 menu for the banquet in Brazza’s honor might allude to this passage from just a few years earlier. The menu also features a giant marmite, yet in contrast to supposed native savagery, the pot offers a vision of french civilization.

Michael Garval, Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

Michael Garval, Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

The post Civilization in Every Pot appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 7, 2017

A Jewish Writer Revived by Her Daughters

By Susan Rubin Suleiman (Guest Contributor)

Fall is the season for the big literary prizes in France. On a November afternoon in 2004, Denise Epstein-Dauplé had just turned on the radio in her kitchen when she heard the announcement: the Renaudot Prize, one of the top fiction prizes, had been awarded to Suite Française, by Irène Némirovsky. Denise, who would be turning 75 the next day, sat down, feeling dizzy. Irène Némirovsky was her mother, whom she had last seen more than sixty years earlier. Arrested by French police in July 1942, in the village where the family had taken refuge at the outbreak of World War II, Irène was deported to Auschwitz, where she died a month later. She was 39 years old. Her husband, deported a few a few months after her, shared the same fate.

And now this prize. No such prize had ever been awarded to a dead author, let alone for a book written half a century before. Suite Française, a novel about wartime France, was the book Némirovsky had been working on when she was arrested. Unfinished, it had never been published, but the manuscript had survived in a suitcase of papers and photographs, the only inheritance her daughters could claim of her. Denise and her sister Elisabeth had known about the manuscript for a long time, and had thought of publishing it. But Elisabeth, who was making a career as a translator and editor in Paris, worried that the novel was unfinished, not quite good enough.

A posthumous publication

It was not until many years later, after Elisabeth had died, that Denise returned to the manuscript and showed it to an editor, who published it immediately. And Denise, who had lived very modestly and in obscurity all her life, became a celebrity in the last decade of her life, invited the world over to speak about her mother. I had the privilege of interviewing Denise several times before her death in 2013, at age 83. She would still choke up on occasion when speaking about her parents—they had disappeared from her life when she was twelve years old. Whenever she spoke about Némirovsky, whether in public or in private, she usually referred to her as “Maman.”

If Suite Française brought Némirovsky back from the dead, a first resuscitation had already been achieved a dozen years earlier, when her younger daughter, Elisabeth Gille, published a book about her (The Mirador). Elisabeth was only five years old when her parents were deported and had very few memories of them, but she had a professional as well as personal interest in her mother’s life and career. The Mirador garnered many positive reviews, and Elisabeth was invited to speak on radio and television about the “once well known writer Irène Némirovsky.” In these interviews, she always referred to her mother by name, not as “Maman.” But one did not have to dig very far to realize that her involvement with Némirovsky was more than that of a biographer.

Discovering Némirovsky

It was through Elisabeth Gille that I first became acquainted with Irène Némirovsky. I read her book and was intrigued. But when I borrowed Némirovsky’s early novel David Golder from Harvard’s Widener Library (most of her books had long been out of print), I found it disappointing. The writing was good, I thought, but conventional, and the story it told was conventional too. Truth to tell, I did not even finish the book.

But that was before Suite Française. I read that novel soon after it appeared and felt deeply moved by it. As a professor of French literature with a longstanding interest in Vichy France, I was astounded by how sharp and accurate Némirovsky’s understanding was of the first year of German occupation, and by her ironic yet often sympathetic view of the French people whose lives she observed. Just as I was telling myself that I had perhaps been too hasty in my dismissal of her earlier work, Némirovsky’s French publishers started reissuing all her novels. I read them, and somewhat to my surprise, became a fan. I wanted to explore further the troubled life and legacy of this writer, as well as the postwar lives of the daughters who brought her back to life. The result is my book, The Némirovsky Question.

Interested in more posts on French literature? Bounce on over to Looking for the Stranger, A Brief History of French Literature Awards, From the Past, With Love, and The Birth of the French Fairy Tale.

Susan Rubin Suleiman’s new book, The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death, and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in 20th-Century France, was published last November by Yale University Press. It has been widely reviewed, in the New York Review of Books, the Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Sunday Times of London among other publications.

Susan Rubin Suleiman’s new book, The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death, and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in 20th-Century France, was published last November by Yale University Press. It has been widely reviewed, in the New York Review of Books, the Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Sunday Times of London among other publications.

The post A Jewish Writer Revived by Her Daughters appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 6, 2017

Can Aristotle Guess Your Personality from Your Face?

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Reading someone’s personality and temperament by looking at his or her face, a “science” known as physiognomy, was accepted by philosophers in classical antiquity. Indeed, the great natural historian Aristotle (fourth century BC) was one of  those who believed that facial features indicated personality type.

those who believed that facial features indicated personality type.

According to little-known passages in History of Animals, Aristotle included physiognomy principles in his detailed descriptions of human faces based on his observations. He started with the forehead: Those with high foreheads were “sluggish,” notes Aristotle, while those with broad foreheads were “excitable.” People with small foreheads were “fickle,” and a bulging forehead revealed a quick-tempered individual. Straight eyebrows were “a sign of a soft disposition” but eyebrows that curve out toward the temples signaled a mocking and evasive personality. Eyebrows curving down toward the nose indicated a harsh temper. People who blinked a lot were indecisive and unstable but those who can stare without blinking were deemed impudent. Aristotle thought ears were especially revealing: Large, projecting ears were a sign that the person indulged in a lot of silly chatter.

The earliest working phyiognomist was Zopyrus in Athens. According to a famous story reported by Cicero (de Fato), Zopyrus read Socrates’ character after observing the philosopher’s face but without knowing him. The reading he gave was so far off the mark that Socrates’ friends in Plato’s academy burst out in guffaws. According to Zopyrus, Socrates’ physiognomy supposedly revealed that he was stupid, dull-witted and lecherous toward women. But Socrates came to his rescue, stating that indeed Zopyrus was correct. Socrates explained that he was naturally inclined to be slow and stupid and addicted to women but that he had–with the help of reason and determination–overcome these character defects.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of  Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

The post Can Aristotle Guess Your Personality from Your Face? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 3, 2017

Five for Friday: Ed O’Loughlin – Minds of Winter

Interview with Ed O’Loughlin

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

My novel weaves together a number of historical and fictional story lines, some of which I encountered in history books, others online. The setting is the polar regions, which have always fascinated me. I suppose, on one level, they are metaphors for a survivable death.

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

I researched the various story lines from history books and online. The overall structure emerged from the notes and rough drafts, with the help of a great deal of time and effort and staring at walls. You sort of lump it all together then scrape away the stuff that you think doesn’t work. There’s no easy way to do it. Or if there is, I don’t know what it is.

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

It was hard to tie all the disparate strands together, and still have an overall story arc that made some kind of sense. Did I manage it in the end? That’s not for me to say.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

My two favourite chapters, which contained the best writing I have ever done, had to be scrapped almost in their entirety. It was my decision to do so – my editor wanted to keep them at first. They meant a lot to me, but they didn’t actually add a thing to the forward movement of the story. I tell myself sometimes that I could resurrect them as stand-alone texts. But who would really want to read them?

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

As a kid I loved the novels of Rosemary Sutcliff, who wrote children’s fiction – they’d call it Young Adult today – set in the distant past. The Eagle of the Ninth and the Lantern Bearers dealt with the decline of the Roman empire in Britain, while Knight’s Fee was about an ill-born young boy who becomes lord of the manor in medieval England. The humanity of her characters and detail of her settings were highly evocative – I can remember them quite clearly forty years later. Unfortunately, she died in 1992, so I can’t tag her into this chain letter.

Ed O’Loughlin was born in Toronto and raised in Ireland. He reported from Africa for the Irish Times and other papers, and was Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age of Melbourne. His first novel, Not Untrue and Not Unkind, was long listed for the 2009 Man Booker Prize. His second novel, Toploader, was published in 2011.

Ed O’Loughlin was born in Toronto and raised in Ireland. He reported from Africa for the Irish Times and other papers, and was Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age of Melbourne. His first novel, Not Untrue and Not Unkind, was long listed for the 2009 Man Booker Prize. His second novel, Toploader, was published in 2011.

The post Five for Friday: Ed O’Loughlin – Minds of Winter appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.