Holly Tucker's Blog, page 4

February 20, 2017

The War Minister and the Runaway Marquise

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Louvois by Larguillère (1680, detail)

Among the many powerful ministers of state who served the French throne, François le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois was one of the most impressive for his effectiveness, perseverance, and ambition. Minister of War under Louis XIV, he greatly expanded the size of the king’s standing army. Under Louvois, the state’s capacity to control its subjects was significantly enhanced.

He also oversaw the development of a network of roads traversing France, and tightened state control of the newly formed postal system. Under his supervision, the state postal system introduced a scheduled system of public transportation. Individual, paying travelers could ride in the postal coach or rent a postal horse.

He also oversaw the development of a network of roads traversing France, and tightened state control of the newly formed postal system. Under his supervision, the state postal system introduced a scheduled system of public transportation. Individual, paying travelers could ride in the postal coach or rent a postal horse.

On a personal level, Louvois was a man whose demands were not easily refused. He was feared for his severity and discipline. Once, he had two of his own sons imprisoned for insubordination. But in an episode that is rarely mentioned in descriptions of his life, he found himself spurned by a clever young woman who showed him how some of his newly designed systems for controlling the king’s subjects could be used instead to enhance their freedom.

Marie-Sidonie de Lenoncourt, the Marquise de Courcelles, had been married at age 16 and was unhappy in her marriage. In 1668 she was 18 when she met the 27-year-old Louvois who was basking in his rapid rise to power. He had just been put in charge of developing the transportation and communication systems in France. He thought that seducing the young Marquise would be an easy matter. But to his chagrin, she not only refused him but she chose another lover. Soon her husband discovered the betrayal and arranged to have her incarcerated for adultery, in a convent in Paris that served also as a prison for wayward wives.

Louvois could have used his influence to get her out, but he did not. Marie-Sidonie then managed to escape by squeezing her tiny self through the grills of the convent parlor. In disguise, she set out on a long journey across France, making careful use of the newly organized public system of postal carriages that would pick up passengers on a regular schedule. She wrote many letters to friends along the way, describing how she plotted her route and arranged to receive supplies in the mail. At one point, finding herself in a town that had no regular postal service, she sent a message to Louvois asking that it be established there.

Marquise de Courcelles, by Nanteuil (1679)

She managed to live this way for nearly 10 years, receiving almost no financial support from her family but enjoying the generosity of a growing network of friends and admirers. When her husband died in 1679, she returned to Paris, thinking it was finally safe for her. By this time, though, her independence was the topic of so much discussion and debate that her in-laws, feeling the family humiliated, decided to pursue the adultery charges that her husband had brought against her. She spent more time awaiting her trial in the Concièrgerie prison, where she was made to recount and justify her travels. But she persisted in writing letters from prison, receiving visitors and admirers, and arguing for the rights of women to leave unhappy marriages and travel independently. Finally, in 1680, she was released in exhange for a heavy fine.

Marie-Sidonie de Courcelles remarried and lived for another five years, dying at the age of 35. She wrote her memoirs and left behind a lively correspondence that was read by many of her contemporaries – especially the female ones – as an inspiration to take to the road in the pursuit of happiness and liberty.

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

The post The War Minister and the Runaway Marquise appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 17, 2017

Five for Friday – Georgia Hunter

Interview with Georgia Hunter

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

I discovered this piece of my family history at fifteen, when my high school English teacher tasked our class with interviewing a relative about our ancestral pasts. My grandfather had died the year before and with his memory so fresh, I decided to sit down with my grandmother. It was in that interview that I learned I was a quarter Jewish, and that I came from a family of Holocaust survivors. Six years later, at a family reunion, I was introduced to pieces of the greater Kurc saga—to stories unlike any I’d ever heard before. Nearly a decade would pass, however, before I gathered the courage to unearth and record my family’s remarkable Holocaust history.

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

My research began in 2008 when I set off with a digital voice recorder to interview a relative in Paris. From there I flew to Rio de Janeiro and across the States, meeting with cousins and friends and strangers—anyone with a story to share. I saved all of my recorded interviews to iTunes and referred back to them frequently. The family’s narrative took shape, at first, in the form of a timeline, which I peppered with historical details and color-coded by relative to help keep track of who was where/when. Where there were gaps in my timeline, I looked to outside resources—to archives, museums, ministries, and magistrates—in hopes of tracking down relevant information. I was amazed at what kinds of information I was able to find. Once my timeline was complete, I plotted an outline and chapter summaries and from there, began the terrifying task of putting my story to paper!

*For more tips on how to conduct your own ancestry search, you can check out the Ancestry Search Tips page on my website.

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

The Kurc family scattered at the start of WWII – their paths to survival spanned five continents over six years. Once I realized the (enormous!) scope of my story, the idea of telling it in a cohesive, digestible narrative was daunting, to say the least. The Kurcs’ diaspora meant that my chapters would have to be written from different perspectives. I thought long and hard on how to differentiate each of my characters, and how to convey thought long and hard on how to differentiate each of my characters, and how to convey those differences on the page in a way that would allow readers to remember who was who as they bounced between storylines. I also created a family tree, which appears at the front of the book, as a tool to help readers remember the characters and relationships.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

Uncovering my family history required so much digging that I was tempted to use every morsel of information I could find! That said, one element of the narrative I opted to omit out where the storylines of a handful of extended family members – great aunts and distant cousins – who also managed to survive the Holocaust. I felt it was already a lot to ask of my readers to keep track of a set of parents, five children/their significant others, and a grandchild. And so, in the end, I decided to narrow my cast of characters to those dozen or so in my grandfather’s nuclear family in order to keep the story focused – and believable.

Hunter penned her first “novel” when she was four years old, and titled it Charlie Walks the Beast after her father’s recently published sci-fi novel, Softly Walks the Beast. When she was eleven, she pitched an article—an Opinion piece on how she’d spend her last day if the world were about to come to an end—to the local newspaper. Since that debut in the Attleboro Sun Chronicle, her personal essays and photos have been featured in places like the New York Times “Why We Travel,” in travelgirl magazine, and on Equitrekking.com. A graduate of the University of Virginia, Hunter has worked in branding and marketing and is currently a freelance copywriter in the world of adventure travel, crafting marketing materials for outfitters such as Austin Adventures and The Explorer’s Passage. She lives in Connecticut with her husband and their five-year-old son.

Hunter penned her first “novel” when she was four years old, and titled it Charlie Walks the Beast after her father’s recently published sci-fi novel, Softly Walks the Beast. When she was eleven, she pitched an article—an Opinion piece on how she’d spend her last day if the world were about to come to an end—to the local newspaper. Since that debut in the Attleboro Sun Chronicle, her personal essays and photos have been featured in places like the New York Times “Why We Travel,” in travelgirl magazine, and on Equitrekking.com. A graduate of the University of Virginia, Hunter has worked in branding and marketing and is currently a freelance copywriter in the world of adventure travel, crafting marketing materials for outfitters such as Austin Adventures and The Explorer’s Passage. She lives in Connecticut with her husband and their five-year-old son.

Missed our previous Five for Friday? Find last week’s interview with Anna Mazzola here. Want to binge read our interviews with fantastic authors? Check out our interviews with Essie Fox, Ami McKay, and Eva Stachniak.

The post Five for Friday – Georgia Hunter appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 16, 2017

Cultural Revolution at the Louvre

By Anka Muhlstein (Guest Contributor)

I am often asked what gave me the idea of writing about the influence of painting on novels of the XIXth century. I was preparing a talk on literary society at the time of Renoir at the Frick, and I immediately thought of Proust because Proust observes how, once Renoir had been accepted as the great painter he is, all the pretty Parisian girls suddenly looked like Renoirs. The painter had literally changed the way reality was perceived. But much as I love Proust, I knew I had to enlarge the subject somewhat and I started reading up the century. I realized quickly that not one of the well-known novelists of the time – Stendhal, Flaubert, Balzac, Zola, the Goncourt brothers, Maupassant, Huysmans – fail to discuss painting or invent characters who are painters. Painting had become a central preoccupation in French literature of the time. What had sparked this interest exclusively in France? This question really obsessed me until it dawned upon me that the reason had to be the opening of the public museum, which was going to be known as the Louvre, in 1793, the most violent year of the French Revolution. Having easy access to great works by visiting a museum feels so normal to us now that we rarely think of the cultural revolution brought about by the advent of modern museums. And yet what a sea change in behavior this opportunity afforded for Parisians.

Everyone visited the Louvre, especially writers and artists—both masters and pupils. The museum attracted the inquisitive and the idle. It was warm in winter, thanks to its modern heating system; there was always something exciting to look at, and it was a respectable place to meet a lady, as she could stroll alone in the galleries without provoking comment. Most important for my purpose, writers acquired a deep understanding of painting and a common language with artists. No wonder novelists of the time tried to establish literary equivalents of pictorial achievements by taking in effect light and color. They truly invented a visual style of writing all the while dreaming up characters that allowed them to air their views on the art of the day and also depict the complex relationship between artists and the general public. There is a world of possibilities between Balzac’s genius Frenhofer, who despairs of ever convincing his fellow artists of his vision, and Proust’s master, Elstir, who has the patience to explain his art like an optician offering a myopic customer lenses of different strength until he can see clearly. At no point in history was the dialogue between painting and writing more intimate and fruitful.

Born in Paris 1935, Anka Muhlstein has published biographies of Queen Victoria, James de Rothschild, Cavelier de La Salle, and Astolphe de Custine; studies on Catherine de Médicis, Marie de Médicis, and Anne of Austria; a double biography, Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart; and more recently, Monsieur Proust’s Library and Balzac’s Omelette (Other Press). She has won two prizes from the Académie Française and the Goncourt Prize for Biography.

Born in Paris 1935, Anka Muhlstein has published biographies of Queen Victoria, James de Rothschild, Cavelier de La Salle, and Astolphe de Custine; studies on Catherine de Médicis, Marie de Médicis, and Anne of Austria; a double biography, Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart; and more recently, Monsieur Proust’s Library and Balzac’s Omelette (Other Press). She has won two prizes from the Académie Française and the Goncourt Prize for Biography.

The post Cultural Revolution at the Louvre appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 14, 2017

A Short History of Valentine’s Day

By Mary Sharratt (Guest Contributor)

The origins of Saint Valentine’s Day lie shrouded in obscurity. Saint Valentine himself, a third century Roman martyr, seems to have nothing to do with the romantic traditions that became associated with his feast.

Dr. Douce, in his Illustrations of Shakespeare, cited in The Book of Days, writes:

It was the practice in ancient Rome, during a great part of the month of February, to celebrate the Lupercalia, which were feasts in honour of Pan and Juno. whence the latter deity was named Februata, Februalis, and Februlla. On this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian church, who, by every possible means, endeavoured to eradicate the vestiges of pagan superstitions, and chiefly by some commutations of their forms, substituted, in the present instance, the names of particular saints instead of those of the women: and as the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, they appear to have chosen St. Valentine’s Day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.

The first mention of Valentine’s Day traditions in England originate from the 14th century writers Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower who both allude to the folk belief that birds choose their mates on the feast of Saint Valentine, their patron.

In Britain, the mating flights of crows, rooks, and ravens can generally be observed by February 14. Here in Lancashire, I notice more and more birdsong each day as February advances and the birds repair their nests, preparing for a new cycle of birth and life.

Around 1440, John Lydgate’s poem in honour of Queen Katherine, widow of Henry V, is the first to mention romantic traditions among humans associated with this date:

To look and search Cupid’s calendar,

And choose their choice, the great affection.

People of both sexes sent tokens of admiration. You could either send a token to the romantic interest of your choice, or draw lots as to who would receive your Valentine. In 1470s Norfolk, the Paston family seems to have preferred drawing lots rather than sending tokens to a chosen person.

Actual Valentines could be quite costly. In 1523, Sir Henry Willoughby, gentleman of Warwickshire, paid 2S, 3d for his. Unfortunately no description of this costly item remains for us today.

After the Reformation, the feast of Saint Valentine was abolished, and yet the amorous traditions flourished.

By 1641, the system of casting lots for Valentines was so well known in Edinburgh that a wag waggishly proposed their new Lord Chancellor be chosen by the same method.

A Dutch visitor to London in 1663 observed:

it is customary, alike for married and unmarried people, that the first person one meets in the morning, that is, if one if a man, the first woman or girl, becomes one’s Valentine. He asks her name which he takes down and carries on a long strip of paper in his hat band, and in the same way the woman or girl wears his name on her bodice; but it is the practice that they meet on the evening before and choose each other for their Valentine, and, come Easter, they send each other gloves, silk stockings, or sometimes a miniature portrait, which the ladies wear to foster the friendship.

In his diaries of the same decade, Samuel Pepys reveals how he would call by a colleague’s house early in the day in order to make the man’s daughter his Valentine. Pepys would also arrange for a young man to call to pay the same homage to Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents, which Pepys then paid for. One year when Pepys was short of cash, alas, no young man with presents appeared and Mrs. Pepys was quite irate. Eventually they settled on a yearly ritual, whereby Pepys’s cousin paid a visit to honour Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents which Pepys knew she desired.

Sources:

The Book of Days

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

Mary Sharratt’s explorations into the hidden histories of Renaissance women compelled her to write her most recent work, THE DARK LADY’S MASK (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2016), based on the dramatic life of the ground-breaking poet, Aemilia Bassano Lanier.

Mary Sharratt’s explorations into the hidden histories of Renaissance women compelled her to write her most recent work, THE DARK LADY’S MASK (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2016), based on the dramatic life of the ground-breaking poet, Aemilia Bassano Lanier.

Born in Minnesota, Mary now lives with her Belgian husband in the Pendle region of Lancashire, England, the setting for her acclaimed novel, DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, which recasts the Pendle Witches of 1612 in their historical context as cunning folk and healers.

The post A Short History of Valentine’s Day appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 13, 2017

What is this thing called lovesickness?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

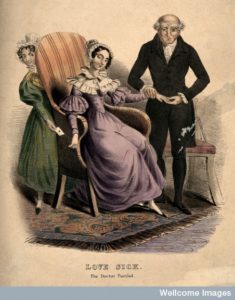

A baffled doctor taking the pulse of a love-sick young woman

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

As Valentine’s Day approaches, now may be the time to check yourself out for a very nasty condition: lovesickness. Are you looking pale? Sleeping badly? Finding it difficult to concentrate? Sighing a lot? Are you off your food? These symptoms, history tells us, may point to lovesickness as your problem.

When is love a disease?

The first stages of being in love, or loving someone who is unavailable, can lead to some physical sensations which in other contexts we’d associate with disease, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that love itself could be understood as a disease. Here’s the character Philetas, in Longus’ novel Daphnis and Chloe, describing his experience: ‘I could not think of food or take drink or get sleep … No, there is no remedy for love, nothing to drink or eat or chant in songs, except kissing, embracing and lying down together with naked bodies.’ Or, from the western medical tradition which drew on the ancient world, here’s Battista Fregoso in his L’anteros ou contramours of 1581: love ‘is not merely behaviour resembling sickness, but it is a true disease, virulent and dangerous’.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. Before we reach the cure, how does the process of cause and effect work? In more recent history, emotions rather than humors have been thought to influence the body. In 1803 the Edinburgh Practice of Physic, Surgery and Midwifery told its readers that ‘love and other passions of the mind’ cause chlorosis, the ‘green sickness’, which was classed here as being the same as ‘chlorosis amatoria’. Strong emotions affected the body and could lead to insufficient menstrual blood being produced by women. Lovesickness and – if it was seen as a separate condition – chlorosis too could be regarded as due to humoral imbalance. This in turn could be traced back to the brain, for Galenic theory the seat of the passions. One way of avoiding the condition was to control the input to the brain: as Jacques Ferrand wrote in his A Treatise on Lovesickness, first published in 1610, ‘Because this carnal love makes its attack upon the brain (the divine fortress of Pallas [Athene]) by the windows of the eyes, you must make sure that no inciting object happens to come into view’.

Who suffers from lovesickness?

In ancient Greek and Roman medicine, both men and women could be affected. If the beloved does ‘come into view’ then, as many physicians from Galen onwards observed, the pulse of the sufferer will speed up. Galen proudly told the story of his diagnosis of the wife of the noble Justus, sick with love for a dancer called Pylades, by feeling her pulse when his name was mentioned. Other stories involved young men whose love for inappropriate love objects – the stepmother or their father’s concubine! – led to serious illness, only detected by a clever physician. Stories of successfully diagnosing a young man suffering from unrequited love were told of Hippocrates and Erasistratus, as well as featuring in Galen.

In her book Lovesickness in the Middle Ages, Mary Wack showed how in this period the condition came to be focused on men rather than on women. Eros, erotic love, was seen as being linked to heroicus, that which belongs to a lord or nobleman. This made it a lot more respectable to be madly in love – it was almost a mark of having the wealth and leisure to indulge yourself in this way!

In humoral medicine, those who were dominated by black bile were thought most likely to suffer from lovesickness. As well as chlorosis, other conditions that formed part of ancient, medieval or Renaissance medicine were believed to overlap with lovesickness; for example, uterine fury and satyriasis. One thing that made it very important to know just which of these was the problem was the question of the best cure.

Getting better

Untreated, lovesickness could lead to death. One problem was that the sufferer may not even want to get better, and without the cooperation of the patient there was little hope. According to Ferrand, all three aspects of healing – diet, drugs and surgery – could make a difference.

By avoiding wine in favor of water, and adopting a cooling diet (lots of sorrel, endives, chicory and lettuce) with nothing spicy or salted, while taking plenty of exercise, Ferrand believed that the symptoms could be alleviated. Kissing and groping should be avoided entirely, but attending a criminal trial or hearing a hellfire sermon could be beneficial. Sleeping on one’s back is very bad as it overheats the kidneys. As for drugs, Ferrand recommended cooling and moistening enemas. Bloodletting could help, using the hepatic vein in the right arm, or in more serious cases the median vein.

Ultimately, however, the one guaranteed cure was to ‘enjoy’ the person who had caused the condition; provided that this was permitted, which would be a problem if the sufferer or the beloved was already married. However, Ferrand notes that sometimes just dreaming about this consummation would suffice! Happy dreaming…

References:

J. Ferrand, A Treatise on Lovesickness (tr. and ed. D.A Beecher and M. Ciavolella, Syracuse University Press, 1990)

M. Wack, Lovesickness in the Middle Ages: The Viaticum and its commentaries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990)

Emotions and disease (National Library of Medicine)

Helen King enjoys sharing ideas about the history of the body and of medicine, whether that means teaching school students on a ‘Roman Medicine’ themed day, lecturing surrounded by body parts in jars at the Bart’s Pathology Museum, or talking to heart surgeons at the Royal Galleries at Holyroodhouse. Her most recent book is The One-Sex Body on Trial: The Classical and Early Modern Evidence (Ashgate, 2013) and, as part of her commitment to distance learning, she has written a MOOC on ‘Health and Wellness in the Ancient World’.

The post What is this thing called lovesickness? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 10, 2017

Five for Friday: Anna Mazzola

Interview with Anna Mazzola

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

I first heard about the crime in Kate Summerscales’ The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. It’s mentioned only briefly, but grabbed my attention as it took place in Camberwell, South London, not far from where I live, and was both peculiar and horrific. The accused, James Greenacre, had distributed the body parts about London, transporting the head by omnibus to Stepney. However, when I read the trial transcript, it was Sarah Gale’s story that gripped me. She was accused of helping Greenacre to conceal the gruesome murder of another woman and yet in both the Magistrates’ Court and the Old Bailey she said almost nothing. Given that she was facing the death sentence, I thought that was very strange. What was keeping her from speaking out?

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

I started off by researching the case itself (through newspapers, the National Archives, Old Bailey online, convict records and pamphlets), then the criminal justice system and Newgate prison. I read prison diaries and parliamentary commissions, I searched for sketches and pictures, and I studied plans of Newgate to get a sense of what that prison might have been like. In terms of the streets outside, I read journalistic works such as Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, the fiction of the period, guidebooks, newspaper reports, court reports, letters, and the journals and memoirs of those who lived in or visited London.

In retrospect, I should have set out clear rules for myself at the outset as to what I needed to research and how much time I would spend on it. I spent over a year researching the Edgware Road murder, London in the 19th century, the status of women and criminal justice. Only a small fraction of that research made it into the book. Really, I should have just written the darned book and then filled in the gaps, which is what I’m doing with my second: broad research, first draft, more detailed research.

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

The biggest challenge was balancing fact with fiction. When I’m working as a solicitor, the facts are all important, but fiction is of course a different matter. As mentioned above, I spent a long time researching the facts of the case, but I spent even longer trying to prise myself away from them in order to write a story that anyone would want to read. That meant, at some points, diverging from the known facts of the case. I agonized over this for many months, and it is one of the reasons that a key theme of the novel is truth/deception. That also came from the case itself – the accounts given at trial and in the newspaper reports are inconsistent, and I became fascinated with how we interpret other people’s stories, and how we narrate our own.

Again, I think it would have helped had I set rules for myself at the beginning of the project: how closely am I going to stick to the historical facts?

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

Originally (and for reasons I can’t explain without ruining the plot) half of The Unseeing was set on a boat. I have therefore read many accounts about 19th century shipping and written what is effectively an entirely separate novel. Maybe one day I will be able to use it for something!

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

I’m tagging Sophia Tobin who has written three excellent historical novels. Her latest, The Vanishing, is a dark and brooding mystery set in the gothic mansion of White Windows on the Yorkshire Moors.

Anna Mazzola is a writer of historical crime fiction and strange short stories. Her acclaimed debut novel, The Unseeing, is published in the US on 7 February 2017. Anna is currently working on a second historical crime novel about a collector of folklore and missing girls on the Isle of Skye in 1857. Anna is also a criminal justice solicitor and child wrangler.

Anna Mazzola is a writer of historical crime fiction and strange short stories. Her acclaimed debut novel, The Unseeing, is published in the US on 7 February 2017. Anna is currently working on a second historical crime novel about a collector of folklore and missing girls on the Isle of Skye in 1857. Anna is also a criminal justice solicitor and child wrangler.

Missed our previous Five for Friday? Find last week’s interview with Essie Fox here. Check out our interview with Ami McKay about The Witches of New York or our interview with Eva Stachniak about her book The Chosen Maiden. Still craving some tidbits about fabulous women? Read our post about “Fashion as Resistance in WWII France” by Anne Sebba.

The post Five for Friday: Anna Mazzola appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 9, 2017

An Untamable Appetite for Wild Birds

By GinaRae LaCerva, Guest Contributor

Thomas Farrington De Voe was overwhelmed by a peculiar obsession. He wanted to describe every article for sale in the raucous public food markets of mid-nineteenth-century New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. A butcher with a stand at Jefferson Market, and a member of a number of historical societies, De Voe stalked the cramped stalls of the markets often, inquiring of the dealers and perusing the bounty.

The variety and quantity of edible wild fowl was especially impressive. In his 1867 book, The Market Assistant, De Voe catalogued a staggering 119 kinds of game birds for sale. Forty varieties of ducks: golden-eyed, sprig-tailed, hairy-headed and dusky. Robins and Blue Jays tied up in strings. Bobolinks, cedar-birds, plover, curlew, night-hawks, rails, thrasher, and thrush.

Bobolink (Dolichonyx Oryzivorus)

To the modern palate, which must contend with just a few kinds of domesticated birds, the quantity and diversity of wild birds available during the nineteenth century sounds fantastical. But for De Voe, it wasn’t just a matter of the stomach. Hidden amongst this array of birds’ feathers was the story of a changing landscape and an entire nation infatuated with chasing distant frontiers.

De Voe was a keen student of history, and he knew he was creating a record of a bounty already in decline. It was just the opposite story when the first European colonists arrived. The wild bird populations had been so immense, the skies seemed demented with wings. “If I should tell you how some have killed a hundred geese in a week, fifty ducks at a shot, forty teals at another,” William Wood wrote in 1634, “it may be counted impossible though nothing more certain.” For British immigrants accustomed to restrictive hunting laws back home—which barred anyone but the nobility from taking game birds and made poaching an offense punishable by death—the abundant fowl in the new world not only helped to fill in the contours of survival, but became a symbol of independence. One simply had to pick up a musket and enter the woods just beyond the homestead to find dinner. There seemed a mob of wildlife so generous, no man could ever have an impact on the prosperity laid before him.

But the untamable appetites of these newcomers had a tremendous impact on bird populations, and De Voe lamented the resulting paucity in his own market. The wild turkey, once found in flocks of a hundred, was now rarely available, and the tame turkeys that could be purchased were far less succulent. The heath hen on Long Island’s Hempstead Plains had once been so cheap and plentiful, it had a reputation of being a poor man’s food, and servants would beg not to eat it more than two or three days a week. But by 1830, they had become a scarce and expensive bird, highly sought after by epicures.

Heath Hens. Illustration by James Turvey, 1835

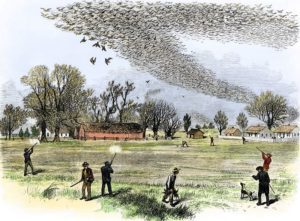

Even the impressive quantities of passenger pigeons De Voe inventoried paled against the seasons of their greatest flights a hundred years before, when nearly seventy-five thousand might be brought to market in a day, and fifty birds were sold for a shilling. The naturalist John Audubon once witnessed a passenger pigeon flight along the Ohio River that crowded out the sun for three days and sounded like the onrush of thunder. When they landed to roost, these convulsions of nature broke as many branches as a tornado. “For a week or more,” he wrote, the locals “fed on no other flesh than that of pigeons, and talked of nothing but pigeons.”

By the time De Voe completed his study in the mid-nineteenth-century, game birds were no longer a mark of homespun self-sufficiency. They had become a market phenomenon. Barrels and bushels of fowl were traded as readily as cash or government bonds, and the rise of gastronomic culture in the urban centers fed this increasingly frenzied speculation. The birds in the prairies were shot in the morning, iced in the afternoon, and sold in New York a day later as a “thing in season.”

Passenger Pigeon Shoot, 1875

Indeed, De Voe was chronicling a very unique moment in U.S. history. The country was divided into sparsely populated hinterlands, dense forests, cultivated fields, and growing cities, creating an extremely varied mix of landscapes not seen at any other time. Concurrently, an expanding railroad and canal system, advances in refrigeration, and new gun technology meant that, for the first time, consumers in metropolitan centers had the chance to purchase products from all over the country. The country poured forth wild-fowl by the millions of pounds.

But the forces that supplied the wild diversity in the market stalls were at the same time the causes of its demise. By the 1880s, the populations of many wild birds were so reduced, their pursuit became unprofitable, and wild birds were almost entirely forgotten as food.

Passenger pigeon by Audubon, 1907

Because of the tremendous destruction of wildlife over the past few centuries, what was once a common practice has become a rare privilege. The passenger pigeon and heath hen are both extinct, and the wild turkeys wander suburban streets looking for the forests of their ancestors. We may never fully comprehend the magnitude of the loss of these birds, but their silenced flights impel us to grasp that the food we eat today is an artifact of this interactive history, and the nature we leave to the future is a map of our own.

GinaRae LaCerva is a writer and researcher in the fields of environmental anthropology, history, and geography, currently completing a Master’s Degree in Forestry at Yale. She is working on her first book, which examines the ecology, economics, cultural history and psychology of eating “wild food” in the modern world.

The post An Untamable Appetite for Wild Birds appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 8, 2017

Blindfolding Babies in the Name of Social Good

By Carolyn Purnell (Guest Contributor)

Diderot, Denis. Lettre sur les aveugles, à l’usage de ceux qui voyent. London, n.p., 1749.

In 1780, the philosopher Jean-Bernard Mérian made a daring proposal to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He thought it prudent “to take [some] children from the cradle and raise them in profound darkness until the age of reason.” To ensure that no light crept in, he added, the children should be required to wear blindfolds.

Sadistic as that may sound, Mérian had good intentions. The experiment was based on the common eighteenth-century idea that the impairment of one sense improves the action of others. Mérian argued that a constant stream of visual impressions distracts from other valuable sensations. Consequently, when “disencumbered of sight,” the children would develop “the most exquisite finesse” with their sense of touch. “Their fingers would be like microscopes,” the delighted Mérian proclaimed.

These tactilely gifted children would be well suited for training in the arts and manual crafts, and theoretically, it would be a win-win situation for everyone. The students would have excellent job prospects, and France would have a talented workforce. Mérian billed this as an appealing option for poor families and argued that mothers should willingly sacrifice their children, with the hope that they could “one day become useful citizens.”

An anonymous reviewer deemed the proposal “elegant, eloquent, and pompous,” but perhaps surprisingly, people did not seem to consider it entirely off-the-wall. In many ways, Mérian’s thought was of a piece with that of other Enlightenment philosophers. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, sensation figured prominently in discussions about commerce, education, and human relationships. Blindness, in particular, was a hot topic.

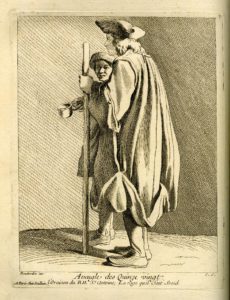

“Aveugle des Quinze-vingt.” Études prises dans le bas peuple; ou, les Cris de Paris, seconde suite. Paris: n.p., 1737. ©Trustees of the British Museum

Prior to the eighteenth century, the blind had largely been relegated to a life of begging, but during the Enlightenment, many philosophers came to view blindness not as a disability but as an asset. For example, in his pedagogical treatise Émile, Jean-Jacques Rousseau recommended that students be educated in the dark. According to Rousseau, sight-reliant individuals are helpless half the time, whereas the blind are always self-possessed. Jean Verdier, who founded a school for future bureaucrats, claimed that physical differences should be embraced, and he, too, lauded the blind: “In blindness, the art of supplanting sight with touch has even been seen to drive the mind to a point of perfection that the majority of men do not reach with all their senses.” And Valentin Haüy, who founded the first school for the blind in 1783, sought to maximize his students’ manual talents by teaching them to work in a printing shop.

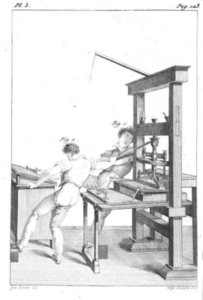

Guillié, Sébastien. Essai sur l’instruction des aveugles, ou exposé analytique des procédés employés pour les instruire. Paris: Imprimé par les aveugles, 1817.

Today, we balk at Mérian’s proposal to blindfold disadvantaged children, and the downsides of his theories are certainly evident. But as far as lessons go, they’re not all bad. For many eighteenth-century social reformers, disabilities were not “dis”-abilities at all. They were distinctive traits filled with social possibility. Philosophers did not aim simply to tolerate or accommodate the blind, instead stressing the unique social benefits offered by blindness. For all their misguided zeal, these reformers embraced difference and recognized its capacity to create a better, fuller, and richer world.

C

C arolyn Purnell received her Ph.D. in European history from the University of Chicago. Her first book, The Sensational Past: How the Enlightenment Changed the Way We Use Our Senses (W.W. Norton & Co., 2017), uses ten episodes to explore the unexpected ways that people put their senses to use in the past.

arolyn Purnell received her Ph.D. in European history from the University of Chicago. Her first book, The Sensational Past: How the Enlightenment Changed the Way We Use Our Senses (W.W. Norton & Co., 2017), uses ten episodes to explore the unexpected ways that people put their senses to use in the past.

Jean Verdier, Cours d’éducation à l’usage des elèves destinés aux premières professions et aux grandes emplois de l’état (Paris: Verdier, Moutard, Colas, 1777), 6-7.

The post appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 7, 2017

We Heart Chocolate: a new podcast!

Valentine’s Day is on the horizon, which means that we will be seeing a lot more chocolate at the grocery store. While it may seem as if there is an abundance of the stuff, we may actually be facing a decline in supply! Over at Gastropod, they have interviewed experts on the history of chocolate, its transformation from currency to candy bar, as well as its medicinal properties — yes, you heard that right! Here’s what the Gastropod team has to say about this exciting episode:

In this episode of Gastropod, we trace chocolate’s journey with chocolate expert Carla Martin and historian Helen Veit, and explore its shifting role from traditional medicine to potential wonder drug with historian Deanna Pucciarelli and Harvard epidemiologist Eric Ding. Along the way, Simran Sethi, author of Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of the Foods We Love, takes us deep into the lush, fragrant, midge-filled humidity of a chocolate forest, only to warn us that these forests, and the precious beans within them, are now facing not just one but multiple existential threats. Listen in now to savor your next chocolate bar that little bit more.

You can follow Gastropod on Twitter @gastropodcast and like them on Facebook. And while you’re at it, check out the Wonders & Marvels Twitter and Facebook pages, too. Happy listening!

Need even more reading on this addictive substance? Look at our previous posts on the chocolate addiction of Marquise de Coëtlogon and its uses in 17th century France.

The post We Heart Chocolate: a new podcast! appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 6, 2017

Chiomara–A Celtic Warrior Woman?

by Adrienne Mayor (monthly contributor)

Modern books and blogs about ancient Celtic warrior women include the story of “Chiomaca,” the wife of Ortiagon, a chieftain of the Gauls (Celts) in the second century BC in Asia Minor (now Turkey). The modern writers claim that Chiomaca “fought and bravely killed a Roman centurion in 186 BC.” But what is the true story?

If we go back to the original ancient accounts, we can set the record straight. First, we learn that this woman’s name was not Chiomaca but Chiomara. She was captured by the Romans in 189 BC (not 186 BC), after Gnaeus Manlius Vulso’s army defeated the Galatians, Greco-Gauls who had settled in Asia Minor. The ancient sources are Plutarch Bravery of Women, Polybius; Livy; Valerius Maximus; and Florus. According to the ancient accounts, Chiomara did not fight in the battle. She was captured along with other Galatian women and slaves. She was raped by a centurion. The centurion then demanded a ransom from Chiomara’s husband Ortiagon. Chiomara, who had been captured with her slave, was allowed to dispatch her slave with the demand for ransom. Ortiagon sent two Galatians to deliver the ransom. The centurion released Chiomara but insisted on embracing her. While his back was turned, either counting the gold or embracing her, Chiomara gave the Galatians a signal to kill the centurion. Chiomara then wrapped the Roman’s head in her robe and delivered it to her husband, saying “Only one man alive should have me.”

It is fascinating to trace how the false tales about Chiomara came to be perpetuated. No ancient Greek or Roman historian ever described Chiomara taking part in the battle, yet typical modern accounts state that in 186 BC the Gaulish soldiers retreated but “Chiomaca stood her ground and killed several Roman soldiers before she was captured [and] raped by a centurion. Later she escaped, found the officer, cut his head off, and presented it to her husband,” writes David Jones in Women Warriors: A History (Potomac Books, 1997, rpt. 2000, 2005), p. 148. Jones incorrectly cites his source as Norma Goodrich, Medieval Myths (1977). In fact, Jones found the story in Jessica Amanda Salmonson’s popular Encyclopedia of Amazons (Paragon House, 1991, p. 57). which states: “Chiomaca: A martial princess of the Gauls . . . captured . . . in 186 BC. . . . She refused to leave the battlefield but raged on with her few companions. When captured, she was raped by a centurion. She subsequently killed the centurion and chopped off his head which she delivered to her husband.” Salmonson’s source was Sarah Hale’s 1855 book, Women’s Record: or Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from Creation to A.D. 1854 (Harper & Bros., 1855, p. 30). In 1855, Sarah Hale spelled Chiomara’s name correctly but she said nothing about Chiomara taking part in the battle. Hale gave an embellished account of the delivery of the ransom. Hale says that the Galatians killed the centurion as he accepted the gold and but she claims it was Chiomara who cut off his head and presented it to her husband.

The truth is that the historical Chiomara did not participate in combat, nor did she behead the Roman centurion herself. But the ancient Greek and Latin sources do tell us that she was a brave and resourceful woman.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, nonfiction finalist 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, nonfiction finalist 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

The post Chiomara–A Celtic Warrior Woman? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.