Holly Tucker's Blog, page 3

March 2, 2017

A Throne Fit for a Courtesan

By Catherine Hewitt (Guest Contributor)

By Catherine Hewitt (Guest Contributor)

Comtesse Valtesse de la Bigne was one of 19th-century Paris’s most ambitious and successful courtesans.

Her thick red hair, pale complexion and enormous blue eyes gave her an unconventional, Pre-Raphaelite appearance which left the Parisian public spellbound. But Valtesse was also disarmingly clever. She was well-read, an accomplished (and self-taught) painter, pianist and novelist, and the author of political pamphlets. Her sharp wit and cool demeanour were legendary, while her connections with painters earned her the nickname ‘The Union of Artists’. She was painted by Édouard Manet and she amassed an enviable collection of paintings, antiques and exquisite objets d’art. She mentored – and had an affair with – the infamous courtesan Liane de Pougy, while her rumoured affairs with Napoleon III and the future king of England, Edward VII, kept gossip columns full. She became embroiled in a scandalous court case, a political intrigue and a horrific murder.

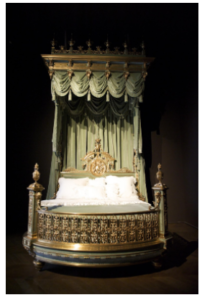

But by far her most famous attribute was her throne-like bed, which Émile Zola used as the model for the ornate piece of furniture commissioned by his anti-heroine in his scandalous novel Nana (1880).

Valtesse was born Louise Delabigne, and raised on one of the most squalid backstreets of Paris. Clawing her way up from the lowest social caste, moving from one rich suitor to the next, she rose to the very top of 19th-century Parisian society. And to mark that ascent, she wanted a courtesan’s throne – a bed.

Valtesse commissioned furniture designer Édouard Lièvre to create a huge Renaissance-style bed. It was modelled on the ceremonial beds used in the mediaeval period by eminent figures (often royalty) when they received visitors to their bedroom. The bed was made of beech and gilt bronze and was over 4m high. Its bedposts supported a large, rectangular canopy, which hovered nearly 3m above the head of the bed, atop of which sat a dome covered in luxurious blue fabric. The canopy was decorated with golden vases and intricate floral trellis work, amongst which the letter ‘V’ could be seen at regular intervals. All around the top of the bed, fauns’ faces smiled down at visitors, while generous swathes of blue velvet cascaded downwards to form magnificent curtains. A circular plaque on the bed head displayed a pair of chubby golden cupids standing either side of Valtesse’s coat of arms. The bed’s circular footboard – a tantalising threshold between Valtesse and her suitors – was decorated with a chain of foliage, while cherubs, fauns and flaming perfume burners completed the decoration on the bedposts. At fifty thousand francs (a third of the price of a mansion at the time), the expense shocked even Valtesse’s friends.

Valtesse commissioned furniture designer Édouard Lièvre to create a huge Renaissance-style bed. It was modelled on the ceremonial beds used in the mediaeval period by eminent figures (often royalty) when they received visitors to their bedroom. The bed was made of beech and gilt bronze and was over 4m high. Its bedposts supported a large, rectangular canopy, which hovered nearly 3m above the head of the bed, atop of which sat a dome covered in luxurious blue fabric. The canopy was decorated with golden vases and intricate floral trellis work, amongst which the letter ‘V’ could be seen at regular intervals. All around the top of the bed, fauns’ faces smiled down at visitors, while generous swathes of blue velvet cascaded downwards to form magnificent curtains. A circular plaque on the bed head displayed a pair of chubby golden cupids standing either side of Valtesse’s coat of arms. The bed’s circular footboard – a tantalising threshold between Valtesse and her suitors – was decorated with a chain of foliage, while cherubs, fauns and flaming perfume burners completed the decoration on the bedposts. At fifty thousand francs (a third of the price of a mansion at the time), the expense shocked even Valtesse’s friends.

Today, visitors can still marvel at the gilt bronze bed at the Musée des Arts décoratifs, in Paris – which is more than the great Alexandre Dumas fils was able to do. When the writer asked to see Valtesse’s bedroom, her reply was quick:

‘That, dear master, no! You could not possibly afford it!’

Catherine Hewitt’s academic career began with a passion for 19th-century French art, literature and social history. Having been awarded a first-class honours degree in BA French from Royal Holloway, University of London, she went on to attend the prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art where she took a Masters in the History of 19th-Century French Art and was awarded a distinction. In 2012, she completed her PhD on The Formation of the Family in 19th-Century French Literature and Art, with joint supervision from Royal Holloway and the Courtauld Institute. Throughout her academic career, she has regularly presented papers at conferences, published work in academic journals and was awarded numerous university prizes.

Catherine Hewitt’s academic career began with a passion for 19th-century French art, literature and social history. Having been awarded a first-class honours degree in BA French from Royal Holloway, University of London, she went on to attend the prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art where she took a Masters in the History of 19th-Century French Art and was awarded a distinction. In 2012, she completed her PhD on The Formation of the Family in 19th-Century French Literature and Art, with joint supervision from Royal Holloway and the Courtauld Institute. Throughout her academic career, she has regularly presented papers at conferences, published work in academic journals and was awarded numerous university prizes.

Catherine lives in a village in Surrey, UK. When she is not writing, she can be found helping restore her family’s house in the middle of rural France, cooking, reading and enjoying country walks with her little black cockerpoo, Alfie.

Don’t miss these interesting posts on Wonders & Marvels related to art, women, and/or France: Cultural Revolution at the Louvre, Chiomara – A Celtic Warrior Woman?, & Fashion as Resistance in WWII France.

The post A Throne Fit for a Courtesan appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

March 1, 2017

Gauguin at the Guillotine

By Aaron Freundschuh (Guest Contributor)

At 2:30am, Paul Gauguin waded into a throng of gawkers on the Place de la Roquette, a few hours before the execution. The winter sky was dark, the air frigid, and the wait, long.

Still another rude discovery awaited the painter. One did not stroll into eastern Paris and simply pluck a prime spot looking on to the guillotine. Barring personal connections or professional duties—Gauguin had neither—unobstructed views of the ceremony were extremely hard to come by.

Just a few days before, in sunny Provence, Gauguin had split with Vincent Van Gogh in a bloody episode that would be understood, but only much later, as a consequential moment in the history of modern art. Having quit the “Studio of the South,” Gauguin was now enjoying a layover en route to Brittany when he made the decision, puzzling on its face, to traverse the French capital in the middle of the night to bear witness to a beheading about which he was dubious.

It was December 28, 1888. The man scheduled to die at dawn was a convict named Prado.

In his retelling of the morning’s events, Gauguin conveys an almost knowing skepticism of Prado’s guilt. In the manner of a detached observer, he scrutinizes the scene, highlighting the rudimentary practices and oversights that characterize the death penalty.

And yet he makes no attempt to conceal the bloodlust that’s driven him to the Place de la Roquette. The crowd stirs as Prado ambles into view, and Gauguin is swept up in the excitement. Guards move to keep control of the situation, shoving Gauguin and others “suddenly, brutally” backward.

But he persists: “I wanted to see, and when I want something, I’m stubborn.” The other onlookers settle into something like a solemn moment, and Gauguin makes a break for it, sprinting forward and plunging for a sightline “between two gendarme boots.”

The blade drops, and the jockeying picks up again. A torrent of obstacles (“three times I was pushed back”) thwart Gauguin and screen him from the money shot: a clear glimpse at Prado’s severed head when it is lifted from its receptacle.

Jug in the Form of a Head, Self-Portrait (Pot en forme de tête, autoportrait; 1889). Photo credit: Designmuseum Danmark, Pernille Klemp.

A Murky Tale

In the aftermath of Prado’s execution, Gauguin conceived his Jug in the Form of a Head, Self-Portrait, a grotesquerie of glazed stoneware that is housed today in the Designmuseum Danmark, in Copenhagen. Generations of art historians, aficionados, and biographers have examined this disquieting piece, a self-portrait-as-death-mask that conveys Gauguin’s interest in the theme of self-martyrdom, as well as his imagination of the messianic mission of the modern artist. There have also been questions—inevitably—about the ears. They are missing on both sides of the piece, in what many have taken as an allusion to Van Gogh.

It is a murky tale, often told: Gauguin and Van Gogh had been quarreling; on December 23, 1888, a portion of Van Gogh’s left ear was sliced off, probably by Van Gogh himself.

Days later, as Van Gogh sat before a mirror to paint the devastating Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, Gauguin, by then in Brittany, dressed his self-portrait jug with expressive red streaks of blood that appear to pool and coagulate around the base of the neck—what he saw, or tried very hard to see, when he craned forward on the Place de la Roquette.

Who Was Prado?

What are we to make of Gauguin’s wish to fire Prado’s ordeal into his own distorted likeness, effectively rendering, together with the allusion to Van Gogh, an odd trinity of fates? While much has been written about the deep ties between Gauguin and Van Gogh, the allure that Prado may have held for Gauguin remains more obscure. Who was Prado?

Gauguin writes that during their nine weeks together he and Van Gogh chatted about the sensational criminal investigations in the news, especially those of two foreigners in Paris: Prado (alias Linska de Castillon), and Enrico Pranzini, a flashy and charismatic young man from Egypt whose case had triggered an immense scandal several months before. Both Prado and Pranzini proclaimed their innocence unwaveringly.

The murder trials of foreigners held great significance in a historical context teeming with populist xenophobia, particularly, as in these two cases, when the suspects were accused of killing high-class Parisian prostitutes. At the time, France was in a fevered state over the perception that violent crime rates were on the rise and immigrants were to blame for it. Although this notion had no basis in fact, its corrosive effects were already apparent in the descriptions of Prado and Pranzini, both of whom had led migratory lives, as “cosmopolitan adventurers,” shapeshifting infiltrators, and serial seducers.

Peruvian Roots

For Gauguin, the outlaw colonial dimension of these cases was bound to be of interest. The stories that trailed Prado—probably apocryphal, but supposedly corroborated by South American immigrants in Paris—were of colorful adventures in Latin America. It was said that he was the son of a Peruvian general, and that he’d frolicked through the Caribbean. Partly as a result, Prado was slurred as a “rastaquouère,” a term that carried the suggestion of racial mixing.

Gauguin cultivated an edgy, colonial-outsider image; he liked to remind people of his “Indian origins.” In fact, as the Prado case neared its climax in the autumn of 1888, he gave Van Gogh a painted self-portrait in which he’d styled himself Jean Valjean of Les Misérables, but with a physiognomy of exaggeratedly exotic features.

It is true that Gauguin’s earliest memories were not of France but instead of Lima, where he spent much of his boyhood. His grandmother, Flora Tristan, had been the illegitimate daughter of a wealthy Peruvian, Tristan y Moscoso, a man of Spanish descent; and the family tree did have its share of political radicals, plus a convict or two.

But of course, Gauguin had the luxury of trading on his own colonial origins from a position of relative privilege. That colonial nostalgia embellished his work is as well known as his turn away from Impressionism in the latter-half of the 1880s, when he experimented in radically new ways with color and perspective.

The self-portrait jug’s colonial accents are multiple. Indeed, it’s been suggested that the genesis of the piece lay in the Peruvian pottery of Gauguin’s mother’s collection. (Art historians have also noted that the jug’s color was obtained using a Japanese technique.) As he had done in his Jean Valjean pose a few months before, Gauguin shaped his jug-likeness with “Incan” facial features.

Prado’s Body

But there is a darker resonance in the object’s fusion of human anatomy and quotidian household decor—a material history now forgotten, but one which the Parisians of Gauguin’s day were forced to reckon with. This history runs through the morning of Prado’s execution.

Prado was one of a series of convicts with colonial ties to be sentenced to death in Paris during 1880s, a group dubbed by one journalist “the great lords of crime.” As it happens, in more than one instance these men had no local next-of-kin to claim their guillotined bodies. By convention, this meant that their corpses were turned over to the Paris Medical School for the purpose of scientific research (the anatomical properties of a convict, foremost the skull, were believed to manifest a biologically criminal essence).

But outrageous rumors—in at least one instance confirmed—swirled around these remains donated to science. With no oversight to prevent them from doing so, workers in the medical school’s amphitheater, as well as doctors, journalists, and policemen, could at times succumb to the temptation to carve up the cadavers, refashioning body parts as souvenirs of a legendary criminal case. Flesh might be used for book bindings or cardholders, a skull for a punch bowl.

So by the time of his execution, Prado had good reason to fear the desecration that awaited his decapitated corpse. In his final hour on death row he rose from bed and—as Paul Gauguin and about 600 other peopled waited impatiently on the other side of the wall—made a statement that startled his captors. “I hereby demand that my body be buried in the ground and not subjected to the experiments of the medical faculty,” he said.

In the absence of protocol relating to such a declaration, a dispute erupted at a nearby cemetery later in the morning between a policeman, a priest, and an aggrieved official from the medical school. Prado’s name lingered in the headlines for another day or two, his last wish having been granted.

For more reading on the career of Paul Gauguin, see Françoise Cachin, Gauguin: The Quest for Paradise (Henry N. Abrams, 1992).

Aaron Freundschuh’s recently published book is, The Courtesan and the Gigolo: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford University Press, 2017).

Aaron Freundschuh’s recently published book is, The Courtesan and the Gigolo: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford University Press, 2017).

The post Gauguin at the Guillotine appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 28, 2017

The First New Orleans Mardi Gras

By Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

By Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

In 1730 a French clerk working in Louisiana found himself in a strange situation. Marc-Antoine Caillot had come there to work for the Company of the Indies. He had embarked on his voyage in the spirit of adventure. In his memoir he would describe himself as a Don Quixote figure, a knight errant, always seeking and sometimes finding romance and pleasure even when reality was looking a bit harsh.

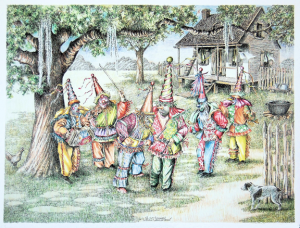

On this occasion in February, all normal business had come to a halt as the residents of New Orleans waited to learn the latest news of an attack on the colony. The Natchez Indians had decided to fight the French who were confiscating their lands. But Caillot, in typical incongruous fashion, was determined to maintain good humor in the face of adversity. “We were already quite far along in the Carnival season without having had the least bit of fun or entertainment,” he writes. His description of what happened next stands now as the earliest description in existence of Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

In an impromptu masquerade, he and his friends dressed themselves in costume, parading through the streets and then following woodland paths until they reached a house outside the city where he knew there was a wedding celebration going on. Caillot was proud of his costume. He had crossdressed as a “French shepherdess, along with plenty of beauty marks, too, and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up.” Others in the group were disguised as Amazons, musicians, and the “Marquis de Carnival.” The party was escorted by “eight actual Negro slaves, who each carried a flambeau to light our way.”

In an impromptu masquerade, he and his friends dressed themselves in costume, parading through the streets and then following woodland paths until they reached a house outside the city where he knew there was a wedding celebration going on. Caillot was proud of his costume. He had crossdressed as a “French shepherdess, along with plenty of beauty marks, too, and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up.” Others in the group were disguised as Amazons, musicians, and the “Marquis de Carnival.” The party was escorted by “eight actual Negro slaves, who each carried a flambeau to light our way.”

When they “had gone a distance of two musket shots into the woods,” the company was terrified by four large bears who the torch-bearers managed with some difficulty to frighten off. The group continued on their way, “laughing about the little drama we had just seen, which had really given us a fright.”

Joining the wedding festivities, the party-crashers were welcomed and their costumes admired, particularly by the ladies. “I believe,” Caillot writes, “without a doubt, that the day was made for lovers.” But with the end of Mardi Gras came a return to reality. “This is how I spent those days in the land of Mississippi,” he concludes. “Now we will get back to the description of the Indian war.”

Joining the wedding festivities, the party-crashers were welcomed and their costumes admired, particularly by the ladies. “I believe,” Caillot writes, “without a doubt, that the day was made for lovers.” But with the end of Mardi Gras came a return to reality. “This is how I spent those days in the land of Mississippi,” he concludes. “Now we will get back to the description of the Indian war.”

For further reading:

Marc-Antoine Caillot, A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, edited and with an introduction by Erin M. Greenwald (Historic New Orleans Collection, 2013).

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith writes on the history of autobiography, women’s writing, letter correspondences, and travel narrative. Her most recent book is a biography of the sisters Hortense and Marie Mancini, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin. She is Professor Emerita of French Literature at Boston University.

The post The First New Orleans Mardi Gras appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 27, 2017

Muslims in the Midwest–Earlier Than You Might Think

Image of the Cedar Rapids mosque courtesy of Jonathunder – (own work, GFDL 1.2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...)

By Pamela D. Toler (Regular Contributor)

If you listen to the news, you’d think that Islamic immigrants to the United States are something new. They’re not.

Beginning in the 1880s and ending only when the United States closed the door on non-European immigrants in 1924, Muslims from Ottoman-controlled Syria joined the rush to emigrate to America. Like their European counterparts, most of the Syrians who came to America were single young men who intended to work for several years and then go home to find wives. Like their European counterparts, most of them made a home and stayed.

The majority of the Syrian immigrants settled in northeastern cities. A few found their way further west. Cedar Rapids, Iowa, became the unlikely home of a growing Islamic community.

The Syrians who settled in the Midwest worked as peddlers, selling dry goods and notions to farm wives in the days before Montgomery Wards and Sears put their catalogs in every rural mailbox. As soon as they could afford it, they sent for their brothers, and then their wives, to join them. The most successful accumulated enough money to open small stores and to stake a new immigrant to his first peddler’s pack. By the 1920s, Arab-owned shops were common in the upper Midwest. In Cedar Rapids alone there were 50 Arab-owned groceries.

The Islamic community of Cedar Rapids soon grew too large to hold the Friday prayer in individual homes. In 1920, they rented a hall and converted it into a mosque. Like the congregation of every storefront church in America, the Muslims of Cedar Rapids dreamed of the day they would worship in a building designed for the purpose. In 1929, they began to build the second American mosque. (The first was built in Ross, North Dakota, earlier that year. It is no longer standing.) The Depression slowed them down, but didn’t stop them. In the best American tradition of barn-raising, young men from the congregation did much of the work themselves. In 1934, the mosque was complete.

The builders of the mosque may have come from the Middle East, but the new mosque was pure Midwest: a small white clapboard building with a cinder-block foundation. The only thing that distinguished it from a country church or a one-room schoolhouse was the small green dome over the front door. Even the crescent-topped spire looked more like a church steeple than a minaret.

In their own way, the Muslims of Cedar Rapids built a domed mosque in the Ottoman tradition. Every Ottoman mosque provided essential social services to the community it served. In sixteenth century Istanbul, that meant attaching a public bath or a soup kitchen to a mosque; in twentieth century America it meant a basement social hall for weddings, parties, and bingo.

Today there are more than one thousand mosques in America. They range in size and stye from unobtrusive storefront prayer rooms to the Islamic Cultural Center on Embassy Row in Washington, D.C. Most are located in buildings originally designed for another purpose: office buildings, bowling alleys, abandoned stores. Like mosques built in Istanbul, Timbuktu, or Jakarta, those built specifically as mosques are constructed in styles and materials that reflect the local community’s ideas about what a mosque should look like. Some use traditional designs borrowed from Islamic lands. Some re-interpret traditional design with American elements. Others are blazingly modern. The one thing they all have in common–with each other and with every other mosque around that world–is that one wall that directs the faithful towards Mecca.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War and is currently working on a global history of women warriors, with the imaginative working title of Women Warriors.

Find Pamela on Twitter at @pdtoler

Read more of her writing on her personal blog

Save

The post Muslims in the Midwest–Earlier Than You Might Think appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 24, 2017

Behind-the-Scenes: This Writer’s Desk

By Holly Tucker, W&M Editor-in-Chief

From Nashville…

From Nashville…

I’m a homebody. I can’t seem to focus when I’m in my campus office, and coffee shops are too noisy.

So when I’m in Nashville, you’ll find me most often upstairs, in a room just off the main bedroom. (I’m usually unshowered and in pyjamas. Or is that TMI? In any case, the neighbors have stopped staring at me when I emerge in my bathrobe to get the afternoon mail.)

When I’m in heavy research mode, I use three computer screens. On the screen to the left, I usually keep open whatever database I’m using (Devonthink or NVivo). The screen to the right is where I have the primary texts, research articles, or web browser open. And in the center, that’s for Scrivener or Word–depending on what stage I am in the writing process. In front of me, I usually have a few books open as well as a pen and a notepad to my left to catch random thoughts and scribbles. (I’m left handed.)

I noticed years ago that I just can’t seem to write unless I’m somewhere near a window. Having a window nearby provides distraction when I’m stuck. I watch the neighbors stroll by as they walk their dogs. Or chuckle at squirrels doing acrobatics in the tree.

I noticed years ago that I just can’t seem to write unless I’m somewhere near a window. Having a window nearby provides distraction when I’m stuck. I watch the neighbors stroll by as they walk their dogs. Or chuckle at squirrels doing acrobatics in the tree.

..To France

But by far, my favorite place to write is at my family’s house in Aix-en-Provence. (No surprise there, right?) No squirrels to be found there, just the sound of the cigales [cicadas]. Over the past few years, I have made it a point to digitize everything that comes across my desk when it comes to book-related things. This lets me keep every thing online, so I can get right to work when I’m there. Sometimes it’s hard to focus, when the weather is nice and the rosé beckons. But that’s where I got the bulk of the writing done for my latest book, City of Light, City of Poison. (By the way, have you ordered your copy yet? Everyone who pre-orders gets a special gift pack–and for the first 40 people, some lavender direct from Provence!)

thing online, so I can get right to work when I’m there. Sometimes it’s hard to focus, when the weather is nice and the rosé beckons. But that’s where I got the bulk of the writing done for my latest book, City of Light, City of Poison. (By the way, have you ordered your copy yet? Everyone who pre-orders gets a special gift pack–and for the first 40 people, some lavender direct from Provence!)

In the Dusty Archives

The most intense work happens, though, at the libraries where I do my archival work. For City of Light, City of Poison, I spent about 4 years going back and forth to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal in Paris. That’s where the court documents, interrogation transcripts and torture notes related to the Affair of the Poisons, the scandal that gripped the City of Light in the late seventeenth century, are held. Some I get digitized, others some I photograph myself. But for the most part, there is no way to get around the laborious work of going patiently–folio through folio–through scores of manuscript volumes. Some days are tedious and do not net much. Other days are euphoric, because you find something in papers that no one has touched for hundreds of years that lets you take one more step toward solving a historical mystery.

Interested in hearing more about Holly’s writing, upcoming book tour, and life in France? Be sure to sign up for her author newsletter!

The post Behind-the-Scenes: This Writer’s Desk appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

Five for Friday: Sophia Tobin

Interview with Sophia Tobin

How did you come across this story? What inspired you to write about it?

I knew that I wanted The Vanishing to be about a foundling (I’ve visited the Foundling Hospital, in London, many times), and I am interested in the complexity of the servant-master relationship. So I made my main character, Annaleigh, an orphan who to goes to work as a housekeeper in a remote Yorkshire house for a mysterious brother and sister. I chose Yorkshire because its combination of beauty and wildness was perfect for the book, and – as a life-long fan of the Brontës – I wanted to re-imagine that landscape in my own way. Other themes which interested me are in there too: love, revenge, imprisonment and drug addiction, to name just a few….

What were your main sources for your research? How did you organize everything? (That is, got any tips for fellow writers?)

I think it’s really important that the location research helps you to create a vivid setting, so I spent time in Yorkshire, making notes and taking photographs. As always, a lot of research took place in libraries, reading about everything from architecture to food, poetry and illness. Studying primary historical sources is my favourite part of the research – I loved reading Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater – and incredibly rich ‘everyday’ sources like the Yorkshire newspapers for the years 1814-15 were invaluable. As for organisation – I just write everything in an enormous notebook, beginning another one when that is full – I don’t tear pages out and rearrange them. That’s my only tip: keep everything in one place – don’t spend more time organising than you do writing!

What were the biggest challenges you faced either in the research, the writing, or structuring the plot?

My biggest challenge (which is also my favourite thing about writing) is that I’m not a plotter – when I start writing I never have more than a few bullet points on plot. I like to surprise myself as well as the reader. The problem with that kind of spontaneity is that it’s easy to lose your way or to find yourself with passages that you love, but which have no place in the final book. That meant that I did have to delete the original beginning of the book. I had worked on it for weeks, and having to remove it really made me feel the pain of that phrase ‘kill your darlings’.

Every writer has to leave something on the cutting floor. What’s on yours?

In addition to the example above, I cut the whole of Annaleigh’s childhood. Initially I wrote 10,000 words on her early years. But, even though I loved that detail, I had a nagging feeling in the back of my mind that it wasn’t serving the story. When I thought analytically about it, I realized: I really need to cut to the chase. So most of it went, with the exception of some scenes which I used in flashback form.

Tag you’re it! What historical fiction author do you most admire? Why? Now forward these questions to him/her and we’ll share their answers next week!

I’m tagging Imogen Robertson, a brilliant author of vivid and page-turning historical fiction, including the Crowther & Westerman series and The Paris Winter.

Sophia Tobin was inspired to write her first novel, The Silversmith’s Wife, by her research into a real-life eighteenth-century silversmith, and she continues to be inspired by the past. Her third novel, The Vanishing, a story of love and revenge, is out now.

Sophia Tobin was inspired to write her first novel, The Silversmith’s Wife, by her research into a real-life eighteenth-century silversmith, and she continues to be inspired by the past. Her third novel, The Vanishing, a story of love and revenge, is out now.

Missed our previous Five for Friday? Read last week’s interview with Georgia Hunter . Want to binge read our interviews with fantastic authors? Check out our interviews with Anna Mazola, Essie Fox, Ami McKay, and Eva Stachniak.

The post Five for Friday: Sophia Tobin appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 23, 2017

Ohio as Paradise during the French Revolution

By Benjamin Hoffmann (Guest Contributor)

Every time I go to work, I cross the Scioto river. It’s a wide, long river in the state of Ohio, streaming on the western side of the city of Columbus. Driving over the bridge, you can glance briefly at the banks of the Scioto where, today, mansions stand tall in the middle of lush vegetation. In the summer, people go stand-up paddleboarding on the Scioto; boats rush on the water and, behind them, wakeboarders attempt daring tricks. In the winter, with blocks of ice floating around, and nobody troubling the stillness of its flows, the Scioto looks much more desolate, and Ohioans quickly leave it behind, as they hurry to find the comfort of their home. Very few of them know that the Scioto used to be seen as the center of an earthly paradise. Very few people know that, at the end of the eighteenth-century, foreigners traveled thousands of miles with the hope of building a utopian society on the banks of this river. Very few people know that these foreigners, French people who had witnessed the beginning of their Revolution, decided to leave behind their homes, their relatives, their homeland, with the hope of creating a peaceful life for themselves on these shores, finding only misery, regrets and, sometimes, death, at the end of their journey.

I discovered this story in 2011, when I started my doctoral dissertation at Yale University. I remember the feeling of excitement I experienced at the Beinecke Library when I read for the first time a travel narrative by a little-known eighteenth-century French philosopher, Claude-François-Adrien de Lezay-Marnésia. Entitled Lettres écrites des rives de l’Ohio, this collection of three missives was published in 1792, when their author came back from a two years’ sojourn in the United States, and, after a second edition in 1800, had never been republished or translated. I immediately knew that I had found a rare gem. A fascinating document, the Letters remind us that, afraid of the cataclysmic changes that shook up French society in the summer of 1789, hundreds of people bought land in what is today Ohio from the American Scioto Company, whose office was located in the center of Paris. Their decision to leave France immediately triggered a fierce political controversy. People picked sides, naming themselves Sciotophiles when they were supporting emigration, and Sciotophobes when they considered it treasonous: why leave France, just when it was freeing itself from the abuse of the Old Regime? Surprisingly enough, an Ohio stream was at the core of a raging political debate in eighteenth-century France, just a few weeks after the storming of the Bastille.

But the Letters are also a beautiful literary text, remarkable for its contribution to the utopian genre. Usually, utopias are located far away in the past or situated in an inaccessible place; Lezay-Marnésia gives a specific location to his perfect society: the banks of the Scioto, which he describes as a “promised land”. The Letters Written from the Banks of the Ohio tell the story of his attempt to create a utopia in the United States and dialogue with the greatest thinkers of its time, in particular Montesquieu and Rousseau. I hope the critical edition of this text, beautifully translated by Alan J. Singerman, will revive this long-forgotten story, along with the following truth: at the outset of the French Revolution, Ohio meant paradise, and people came from half a world away to see it.

Benjamin Hoffmann is Assistant Professor of Early Modern French Studies at The Ohio State University. He is the author of four novels and numerous articles on eighteenth-century French Literature. His next book, Posthumous America: Literary Reinventions of America in French Literature at the end of the Eighteenth-Century, is forthcoming in French and English translation from Classiques Garnier and Pennsylvania State University Press.

Benjamin Hoffmann is Assistant Professor of Early Modern French Studies at The Ohio State University. He is the author of four novels and numerous articles on eighteenth-century French Literature. His next book, Posthumous America: Literary Reinventions of America in French Literature at the end of the Eighteenth-Century, is forthcoming in French and English translation from Classiques Garnier and Pennsylvania State University Press.

Dreaming of an escape to utopia? Have a look at Communism on Mars and Feminist Fairies and Hidden Agendas.

The post Ohio as Paradise during the French Revolution appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 21, 2017

Bottoms Up: Drinking on U.S. Commercial Airliners

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Drinking and flying have long and intertwined histories. For some commercial air passengers, consuming alcoholic beverages is an essential part of the experience of traveling by plane.

A Northwest Airlines Boeing Stratocruiser, the airliner that made it possible to serve drinks during domestic flights.

During the Prohibition Era in the United States, when many commercial airlines first formed and began carrying passengers, carriers did not serve drinks. Even so, customers anxious about flying sometimes sneaked drinks aboard in bottles labeled for medicines or other products. PanAm was among the first to serve alcoholic beverages on international flights in the late 1940s, and National Airlines offered drinks on some flights between New York City and Miami, but only when the aircraft was outside the territorial limits of the U.S.

The first real innovator in the serving of alcoholic drinks on American domestic routes was Northwest Airlines. The arrival in 1949 of Northwest’s fleet of Boeing Stratocruiser airliners, with their large kitchen galleys and dining spaces, made pouring drinks for passengers a possibility.

Northwest introduced its cabin attendants to the art of preparing drinks through training programs and by publishing such pamphlets as “The Story of Distilled Beverages” for crew members.

For passengers, potent drinks gave flying a wholly new feeling, but it also raised thorny legal issues. Although Northwest maintained that the sky should remain free of the drinking limitations and regulations that ground-level state governments wanted to impose, legislators and attorneys general believed differently. Northwest eventually had to seek airborne liquor licenses from each state its routes passed over. Illinois and New York refused to grant any license, and other states imposed their own restrictions and requirements.

So when taking off from New York City, Northwest crews had to delay the drink preparations until the Hudson River was behind them. Over Michigan and Washington State, they had to collect sales taxes. Many states were dry on Sundays and on Election Day. “Over South Dakota, it is illegal to serve a spendthrift, but Northwest hasn’t yet challenged a passenger under this statute,” observed a lengthy 1950 article in The New Yorker.

Because of limited space in the galleys, Northwest initially excluded beer and champagne from its beverage selections and stuck to martinis, scotch, manhattans, and whiskey. “For mixing purposes, you can have ginger ale, soda water, or, heaven forbid, Coca-Cola,” The New Yorker’s writer noted. “During a descent, no one is allowed to hold the glass, lest he accidentally bite into or swallow it at touchdown.”

PanAm, National, and Northwest have all disappeared, but the trails they blazed in serving alcohol continue to guide the drinking habits of passengers.

(This post is adapted from Jack El-Hai’s book Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines, University of Minnesota Press.)

Further reading:

“Food Timeline: Airline Food.” Foodtimeline.org.

Foss, Richard. Food in the Air and Space: The Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

The post Bottoms Up: Drinking on U.S. Commercial Airliners appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

Black History: Frederick Douglass, Civil Rights on Pinterest, & Desegregating Blood

By April Stevens (Former W&M Editorial Assistant)

Our recent series on Wonders & Marvels has reflected on some uncommon perspectives and previously untold stories in black history across the globe. This week, our Cabinet of Curiosities finishes this series by offering you a few more unique ways to look at black history, both figuratively and literally.

Picture This

Picture This

We all know a picture is worth a thousand words, but when it comes to civil rights, Frederick Douglass knew it could mean so much more. He believed making pictures enables us to “see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.” In this spirit, take a look at Time’s feature of iconic photographs from African American History that give us a glimpse into African American culture of the past.

Wishing that you could visit black history heritage sites, but don’t have the funds or time? The Huffington Post highlights a Pinterest board that takes you on a virtual journey of important civil rights landmarks across the United States. Step back in time yourself by following the civil rights movement on the Pinterest board!

Wishing that you could visit black history heritage sites, but don’t have the funds or time? The Huffington Post highlights a Pinterest board that takes you on a virtual journey of important civil rights landmarks across the United States. Step back in time yourself by following the civil rights movement on the Pinterest board!

Blood, Books, and Black History?

The desegregation of schools and public places has been much studied, but you probably haven’t given much thought to the desegregation of the blood supply. Thomas A. Guglielmo illustrates how the battle for civil rights extended to every part of society in his article “Desegregating Blood: A Civil Rights Struggle to Remember”.

The desegregation of schools and public places has been much studied, but you probably haven’t given much thought to the desegregation of the blood supply. Thomas A. Guglielmo illustrates how the battle for civil rights extended to every part of society in his article “Desegregating Blood: A Civil Rights Struggle to Remember”.

Don’t miss these interesting posts on Wonders & Marvels related to Black History:

Black Women, Violence, and American History

Toni Stone: The First Woman in Men’s Professional Baseball

A Shocking Art Exhibition about Lynching

Finding Freedom in Paris: African American Women in the Jazz Age

The post Black History: Frederick Douglass, Civil Rights on Pinterest, & Desegregating Blood appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

February 20, 2017

Mr. President, a Visitor Is Here to See You

By Jack El-Hai (Regular Contributor)

Thousands of people will soon arrive in Washington, D.C., for President Obama’s inauguration. Who are the people who visit the nation’s capital to see the Chief Executive? For the past 70 years, researchers have wondered about the psychiatric makeup of the President’s visitors — especially those visitors who are psychotic.

Three studies in separate decades have scrutinized psychotic visitors to the White House.

From the 1940s

The first study, published in 1943 by Jay L. Hoffman, a psychiatrist at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, examined a group of 53 St. Elizabeths patients, about half of whom had been committed to psychiatric treatment years earlier after showing strange behavior and being turned away at the White House. (The remainder had been hospitalized after their bizarre conduct at other government offices in Washington.) Many had hoped to complain to the President about injustices they believed they experienced in finding employment, being previously confined to mental hospitals, and collecting financial payments they thought they deserved. Some wanted to give advice on matters of national importance. “Two claimed that they had been elected to the office of the President of the United States and came to Washington to be sworn in,” Hoffman wrote.

Hoffman sought patterns and common traits among the psychotic patients and found disproportionate numbers of paranoid schizophrenics, foreign-born people, and unmarried men among them. “Frequent references were made in the records indicating frustration in sex life and poverty of sex-experience,” Hoffman observed. “Delusions and hallucinations referring prominently to sex functions and sex organs were common.”

He wrote that most of these patients notably lacked insight, although they often were pleasant and polite despite their delusions. Few recovered their mental health. Hoffman concluded that members of this group were “a pitiful lot” whose presidential visits were but a single sign of their illness that left them isolated, unsuccessful, and frustrated.

From the 1960s

A 1965 study by Joseph A. Sebastiani and James L. Foy, psychiatrists with the University of Cincinnati and Georgetown University respectively, revisited the phenomenon of psychotic visitors to the White House. They went through the records of 38 patients referred for psychiatric treatment after seeking an audience with the President during the early 1960s. The patients ranged in age from teenagers to an 86-year-old man. Among them were five people in pursuit of property or sums of money, three presumptive presidents, two on “top secret” missions, one self-declared presidential wife, and a woman who claimed to be President Eisenhower’s mother. The psychiatrists characterized the group as “profoundly delusional individuals seeking an exclusive personal encounter with the President and an extraordinary association with the complexly symbolic office of the Presidency.” Nearly all had received diagnoses as paranoid schizophrenics.

The researchers raised the possibility that any similarities among the patients may result from profiles of White House visitors suitable for psychiatric referral that the Secret Service had developed. Sebastiani and Foy concluded that few of the patients had presented actual physical threats to the President.

From the 1980s

Twenty years later, a research team from St. Elizabeths Hospital and the National Institutes of Mental Health took yet another look at psychotic White House visitors. They reviewed the cases of 328 people sent between 1970 and 1974 to St. Elizabeths after problematic attempts to see the President. Like the previous studies, their research showed the patients to be predominantly white, male, unmarried, and paranoid schizophrenic.

Unlike earlier researchers, however, this team found few foreign-born among the patients, and they discovered that 22 percent of the group had made written or verbal threats against the President and other government officials. These psychotic visitors did not view the Chief Executive and his minions as paternalistically as had their counterparts of earlier decades. One of the 328, in fact, went on to murder a Secret Service agent, another attacked a security officer at the Department of the Treasury, and a third assaulted a person she had mistaken for the First Lady.

If you are attending the presidential inauguration this month, enjoy yourself. Just steer clear of all who say they’re seekers of lost fortunes or pretenders to the Oval Office.

Sources:

Hoffman, J.L. Psychotic visitors to government offices in the national capital. Am J Psychiatry 99:571-575, 1943

Sebastiani, J.A., Foy, J.L. Psychotic visitors to the White House. Am J Psychiatry 122:679-686, 1965

Shore, David, Filson, C. Richard, Davis, Ted S., Olivos, Guillermo, DeLisi, Lynn, Wyatt, Richard Jed. White house cases: psychiatric patients and the Secret Service. Am J Psychiatry, 142:308-312, 1985

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

The post Mr. President, a Visitor Is Here to See You appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.