Holly Tucker's Blog, page 6

January 17, 2017

When Extortionists Targeted Hollywood’s Art Linkletter

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Art Linkletter had a long career in radio and TV as a show host, comedian, and pitch man. Before his death in 2010, Linkletter and I had a complicated relationship. In 1967 I was a kid featured in the closing minutes of one of his popular and nationally broadcast House Party TV episodes — the part of the show in which Linkletter asked children questions and made them unwittingly say funny — or “the darndest” — things in response.

Art Linkletter in 1957

My encounter with Linkletter disturbed me, and I afterward followed his career. I grew to regard him as a man needy of attention whose family tragedies and conservative opinions carried him along strange paths. (If you’d like to read more about my appearance on his show, I’ve written about it here.)

When I learned that the FBI’s file on Linkletter had been released to the public, I had to take a look. I found that the file included details of two extortion attempts against Linkletter, plus a bit of information on the celebrity’s own minor wrongdoing.

The first extortion attempt

The file opens with documents chronicling an attempt in 1954 to extort money from Linkletter, who was then 41 and already famous for his work in broadcasting. Linkletter received two threatening messages, and like clichéd ransom notes in a movie, both were assembled from letters cut out from newspapers and magazines. The first demanded $1,000 and threatened harm to Linkletter’s daughter. The second, sent after Linkletter did not respond to the first, read, “This is it. Your last chance. Your children are nest [sic]. Rat”

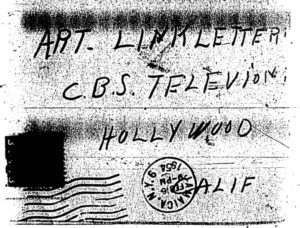

An envelope used in the 1954 extortion attempt

Postmarks showed that both letters were mailed from Jamaica, N.Y., a city on Long Island where Linkletter had no known acquaintances or enemies. The celebrity said he was not frightened, but the FBI sprang into action. Assuming the letters to be the work of a child, the agency spent the next several weeks collecting 4,779 writing samples from junior high and high school students in the Jamaica area. Agents found no matches with the hand printing on the extortion letter envelopes. “Inasmuch as logical investigation has failed to identify the unknown subject and there are no leads outstanding,” an agent wrote in admirable FBI bureaucratese four months after the case began, “this matter is closed.”

The next extortion attempt

Linkletter was again victimized four years later, but this time he was in illustrious company: the extortionist simultaneously sent letters to Linkletter, Vice President Richard Nixon, and Georgia Senator Herman Talmadge. The perpetrator threatened Linkletter’s sons, demanded $700, dropped a .22 caliber bullet into the envelope, and conveniently included his full name and mailing address in Molena, Georgia, along with the admonition, “Don’t fool around.” (He demanded only $200 from Nixon and Talmadge.)

The local sheriff quickly arrested the extortionist, an unemployed, red-haired and freckled 18-year-old, who under questioning by FBI agents admitted to sending the letters. He had spent time as a psychiatric patient at Milledgeville State Hospital. He said he needed the extortion money to go to Florida and find a job. The U.S. Attorney in Los Angeles declined to prosecute him, and the file does not mention his ultimate legal disposition.

A false statement

The final pages of the FBI’s file on Linkletter concern a security questionnaire the entertainer filled out in 1959 when he joined the board of directors of Cohu Electronics, a U.S. military contractor. In that questionnaire, Linkletter was found to have falsely stated that he had never been arrested. In fact, as the FBI discovered, Linkletter had been arrested and convicted in 1942 for making a false affidavit of citizenship. (Born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, he did not actually become a U.S. citizen until 1947.) Linkletter paid a $500 fine for the 1942 infraction. His penalty for making the false statement in the security questionnaire, if there was any, is unknown.

Further reading:

Federal Bureau of Investigation. File on Art Linkletter.

Linkletter, Art. Hobo on the Way to Heaven: An Autobiography. David Cook, 1980.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WW2 (PublicAffairs Books) and Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press). He frequently writes articles on history and the history of medicine for such publications as Discover, The Atlantic, Aeon, Scientific American Mind, Longreads, and The Washington Post Magazine (among many others), and he has given presentations for the American Psychological Association, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Mayo Clinic, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, and other universities and medical schools.

The post When Extortionists Targeted Hollywood’s Art Linkletter appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 16, 2017

Looking for the Stranger

By Alice Kaplan (Guest Contributor)

How did Camus come up with the name for Meursault, the hero of The Stranger ? His is one of the most famous names in modern literature, and one of the most mysterious.

In the late 1930s, Camus drafted a first novel he called A Happy Death. He revised it many times but was never satisfied, and finally put it away in a drawer. The main character of that novel was a man named Patrice Mersault—Meursault minus the “u.”

It’s worth taking a look at the two names—Mersault and Meursault—and thinking about how Camus might have gotten from one to the other. When you pronounce “Mersault” without the “u,” it sounds ethnically Spanish, like “Merso.” “Merso” is a name that could have belonged to heavily Spanish ethnic Europeans who lived in Oran, or to a kin of Camus’s mother Catherine Sintès, whose people were from Minorca. But Meursault is different. For any French reader, that name can only signify the delicious and expensive white Burgundy wine.

I was really shocked when I looked at the only surviving manuscript of The Stranger and discovered that Camus writes his character’s name without a “u” throughout. Where did that “u” come from ? Some Camus experts claim he thought of the name change at a dinner party where he was served an especially good bottle of the Burgundy wine. Then there’s the story of the contest. Every November, a literary prize of 3,000 bottles of Meursault wine was awarded to a book celebrating the glory of the land. An ad for the prize appeared in the French press in November, 1941, as Camus was putting finishing touches on his novel. Although Meursault isn’t a very funny guy, Camus himself had a great sense of humor, and I can imagine him joking to his friends that naming his main character “Meursault” was a sure way to win the prize.

I was really shocked when I looked at the only surviving manuscript of The Stranger and discovered that Camus writes his character’s name without a “u” throughout. Where did that “u” come from ? Some Camus experts claim he thought of the name change at a dinner party where he was served an especially good bottle of the Burgundy wine. Then there’s the story of the contest. Every November, a literary prize of 3,000 bottles of Meursault wine was awarded to a book celebrating the glory of the land. An ad for the prize appeared in the French press in November, 1941, as Camus was putting finishing touches on his novel. Although Meursault isn’t a very funny guy, Camus himself had a great sense of humor, and I can imagine him joking to his friends that naming his main character “Meursault” was a sure way to win the prize.

Certainly Camus had other reasons to make the change. First there is something more expected about the way Meur-sault sounds to a French ear than Mer-sault. Then again, the extra “u” makes the first syllable of his character’s name signify death meur (death), which serve the purposes of a story in which Meursault commits murder and waits to die at the guillotine.

I have another theory about the name change, but no way to prove it. In the early spring of 1942, Camus was in Oran, Algeria, deathly sick with tuberculosis. So he asked his publishers to proof read the pages of the novel for him, in Paris. Is it possible that they took matters into their own hands, or that they checked with the author in a communication that is lost to us, and changed Mersault to Meursault on publisher’s page proofs ? Some of the greatest moments in world literature are the result of a last minute, last second cross outs. We’ll never know if this is one of them.

I have another theory about the name change, but no way to prove it. In the early spring of 1942, Camus was in Oran, Algeria, deathly sick with tuberculosis. So he asked his publishers to proof read the pages of the novel for him, in Paris. Is it possible that they took matters into their own hands, or that they checked with the author in a communication that is lost to us, and changed Mersault to Meursault on publisher’s page proofs ? Some of the greatest moments in world literature are the result of a last minute, last second cross outs. We’ll never know if this is one of them.

Alice Kaplan is the author of French Lessons: A Memoir, The Collaborator, The Interpreter, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and Looking for The Stranger. She is the translator of OK, Joe, The Difficulty of Being a Dog, A Box of Photographs, and Palace of Books. Her books have been twice finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Awards, once for the National Book Award, and she is a winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She holds the John M. Musser chair in French literature at Yale. She lives in Guilford, Connecticut.

Alice Kaplan is the author of French Lessons: A Memoir, The Collaborator, The Interpreter, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and Looking for The Stranger. She is the translator of OK, Joe, The Difficulty of Being a Dog, A Box of Photographs, and Palace of Books. Her books have been twice finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Awards, once for the National Book Award, and she is a winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She holds the John M. Musser chair in French literature at Yale. She lives in Guilford, Connecticut.

The post Looking for the Stranger appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 13, 2017

Blindfolding Babies in the Name of Social Good

By Carolyn Purnell (Guest Contributor)

In 1780, the philosopher Jean-Bernard Mérian made a daring proposal to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He thought it prudent “to take [some] children from the cradle and raise them in profound darkness until the age of reason.” To ensure that no light crept in, he added, the children should be required to wear blindfolds.

In 1780, the philosopher Jean-Bernard Mérian made a daring proposal to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He thought it prudent “to take [some] children from the cradle and raise them in profound darkness until the age of reason.” To ensure that no light crept in, he added, the children should be required to wear blindfolds.

Sadistic as that may sound, Mérian had good intentions. The experiment was based on the common eighteenth-century idea that the impairment of one sense improves the action of others. Mérian argued that a constant stream of visual impressions distracts from other valuable sensations. Consequently, when “disencumbered of sight,” the children would develop “the most exquisite finesse” with their sense of touch. “Their fingers would be like microscopes,” the delighted Mérian proclaimed.

These tactilely gifted children would be well suited for training in the arts and manual crafts, and theoretically, it would be a win-win situation for everyone. The students would have excellent job prospects, and France would have a talented workforce. Mérian billed this as an appealing option for poor families and argued that mothers should willingly sacrifice their children, with the hope that they could “one day become useful citizens.”

An anonymous reviewer deemed the proposal “elegant, eloquent, and pompous,” but perhaps surprisingly, people did not seem to consider it entirely off-the-wall. In many ways, Mérian’s thought was of a piece with that of other Enlightenment philosophers. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, sensation figured prominently in discussions about commerce, education, and human relationships. Blindness, in particular, was a hot topic.

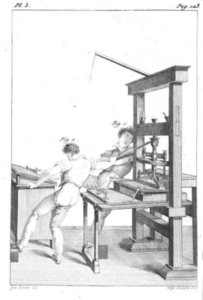

©Trustees of the British Museum

Prior to the eighteenth century, the blind had largely been relegated to a life of begging, but during the Enlightenment, many philosophers came to view blindness not as a disability but as an asset. For example, in his pedagogical treatise Émile, Jean-Jacques Rousseau recommended that students be educated in the dark. According to Rousseau, sight-reliant individuals are helpless half the time, whereas the blind are always self-possessed. Jean Verdier, who founded a school for future bureaucrats, claimed that physical differences should be embraced, and he, too, lauded the blind: “In blindness, the art of supplanting sight with touch has even been seen to drive the mind to a point of perfection that the majority of men do not reach with all their senses.” And Valentin Haüy, who founded the first school for the blind in 1783, sought to maximize his students’ manual talents by teaching them to work in a printing shop.

Today, we balk at Mérian’s proposal to blindfold disadvantaged children, and the downsides of his theories are certainly evident. But as far as lessons go, they’re not all bad. For many eighteenth-century social reformers, disabilities were not “dis”-abilities at all. They were distinctive traits filled with social possibility. Philosophers did not aim simply to tolerate or accommodate the blind, instead stressing the unique social benefits offered by blindness. For all their misguided zeal, these reformers embraced difference and recognized its capacity to create a better, fuller, and richer world.

Today, we balk at Mérian’s proposal to blindfold disadvantaged children, and the downsides of his theories are certainly evident. But as far as lessons go, they’re not all bad. For many eighteenth-century social reformers, disabilities were not “dis”-abilities at all. They were distinctive traits filled with social possibility. Philosophers did not aim simply to tolerate or accommodate the blind, instead stressing the unique social benefits offered by blindness. For all their misguided zeal, these reformers embraced difference and recognized its capacity to create a better, fuller, and richer world.

C

C arolyn Purnell received her Ph.D. in European history from the University of Chicago. Her first book, The Sensational Past: How the Enlightenment Changed the Way We Use Our Senses (W.W. Norton & Co., 2017), uses ten episodes to explore the unexpected ways that people put their senses to use in the past.

arolyn Purnell received her Ph.D. in European history from the University of Chicago. Her first book, The Sensational Past: How the Enlightenment Changed the Way We Use Our Senses (W.W. Norton & Co., 2017), uses ten episodes to explore the unexpected ways that people put their senses to use in the past.

Jean Verdier, Cours d’éducation à l’usage des elèves destinés aux premières professions et aux grandes emplois de l’état (Paris: Verdier, Moutard, Colas, 1777), 6-7.

The post appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 11, 2017

Disgusting Truth: What Can Foul Food Reveal about Trump?

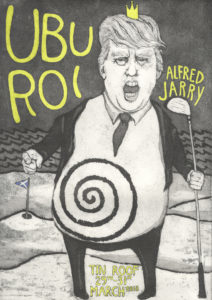

Fig. 1: Alfred Jarry, “Veritable Portrait of Monsieur Ubu,” woodcut from the original edition of the play (1896).

By Michael Garval (Regular Contributor)

In this inaugural ball season, the scatological feast in Act I of Alfred Jarry’s 1896 Ubu Roi offers an apt parody of political festivities past and present.

In the play, the cruel, rash, greedy, childish, vulgar, vengeful philistine Ubu (Fig. 1) seizes power on a whim. His short reign proves disastrous.

Political interpretations of Jarry’s groundbreaking, iconoclastic work have varied over time. At first, Ubu seemed to embody 1890s anarchist agitation (Jarry called him the “perfect anarchist”), or absolute political mediocrity (painter Paul Gauguin described him as a quintessentially “vile,” “crappy” politician). In the twentieth century, Ubu came to be seen as an authoritarian despot, for example with painter Joan Miró ringing variations on Ubu to decry Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Of late, Ubu has resurfaced in critiques of US president-elect Donald Trump, with various Trump-inspired versions of Ubu Roi playing in Seattle, Minneapolis, Richmond, and Lubbock, Texas. The first such comparison even predates his candidacy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Finnish graphic artist Iida Lanki explains the genesis of her 2013 poster, reinterpreting Ubu Roi: “I had recently seen Anthony Baxter’s documentary ”You’ve Been Trumped” which follows the construction of a luxury golf course in Scotland. The antics of Donald Trump were autocratic and quite malicious even then. Thus when I was given Ubu Roi to work with, the character reminded me of the documentary and Trump was a natural inspiration. Later I have reflected how uncanny it all seems now, when he truly has power over things.”

The play’s opening line scandalized the audience at its Parisian premiere. Ubu bellows “Merdre!”—adding an extra “r” to merde, or shit in French—a scarcely euphemistic coinage rendered in English as “pshit,” “shite,” or “shitsky.” In the play, this oft-hurled expletive also figures in the banquet as an ingredient. But how, and why?

Eat shit and die

Once “Mama Ubu” convinces her husband to overthrow King Wenceslas of Poland, they invite Captain Bordure and his partisans to dine, to enlist their help. Even before guests arrive, impatient, gluttonous Ubu sneaks pieces of roast chicken and veal. The meal’s long list of dishes apes festive dinners from the period: Polish soup, “drat chops,” veal, chicken, dog pâté, turkey rumps, charlotte russe, bombe glacée, salad, fruit, dessert, boiled beef, Jerusalem artichokes, and “cauliflower à la shitsky.” But this anarchic menu, served in no particular order, mixes refined banquet items with nonsensical and frankly revolting ones.

The dynamic at table is just as chaotic. Guests vacillate between disgust and delight; hosts between hospitality and hostility. In a particularly unsettling sequence Ubu leaves, then returns with a surprise as the guests are praising their hostess’s cooking with cries of “Long live Mama Ubu!” “And soon you’ll be shouting long live Papa Ubu,” he declares, heralding his imminent coup d’état while holding a dirty toilet brush, which he throws upon the feast. “Try a little,” he adds, and the stage directions note: “Several taste and fall down, poisoned.” Abandoning polite dinner party pretense, the scene pivots from whimsical merdre to noxious merde.

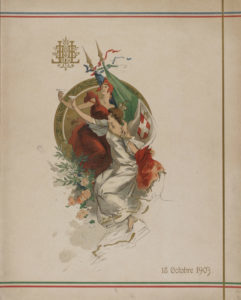

Fig. 3: Jules Chéret, French state luncheon menu, October 18, 1903, hosting the King and Queen of Italy (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris).

Ubu, like Trump, is a perplexing phenomenon. Politically, Ubu’s rise remains unimpeded by his disregard for others, even his ostensible allies. Gastronomically, Ubu short circuits the normal order of things, substituting output for input, as he serves up excrement instead of food (Jarry, who identified closely with his character, preferred eating meals backwards, from dessert to soup). And politics and gastronomy intertwine, as Ubu’s odious gesture at table presages his ruthless regime ahead. In colloquial English his message to the people would be “Eat shit and die.”

Inaugural festivities

In France, the 1880s through the start of the Great War were what the title of Roger Shattuck’s landmark study called “the banquet years.” Paris in particular offered a metaphoric feast of spectacle, drama, agitation, and ferment across society, politics, and the arts, echoed by more literal banquets—elaborate, multi-course affairs, showcasing French culinary preeminence in the age of Escoffier.

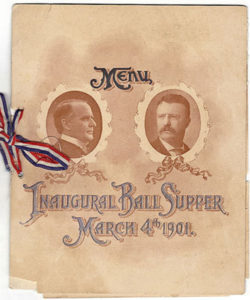

Fig 4: William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt’s Inaugural Ball Supper Menu, March 4, 1901.

The Ubus’ disconcerting dinner takes aim at this sort of extravaganza, and especially at the period’s frequent political banquets, like this 1903 French state luncheon hosting the King and Queen of Italy (Fig. 3). And US inaugural balls at the turn of the century emulated such Gallic models. For example, the 1901 supper menu for President William McKinley and Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural ball details a cornucopia of fancified dishes, in bad culinary French—Consomme de Volaille a’ la reine, Essence de Molusque, Homard farcis, Croquettes Exquises aux petits pois, etc. —though puritan abstemiousness governs the beverage options, with only Apollinaris water and coffee listed (Fig. 4).

These days, inaugural galas feature “heavy hors d’oeuvres” and carving stations, rather than endless sit-down dinners. But wining, dining, dancing, and schmoozing remain the order of the day. These events still offer a ceremonial interlude before the new regime swings into action, a time for anticipation and speculation. Politically, the Trump campaign and transition have prompted great apprehension; gastronomically, the prospects are worrisome as well, with Trump Grill recently described as “the worst restaurant in America.”

So, amid inaugural festivities, might there be further clues about the sort of merde to be served over the next four years?

Michael Garval, Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

Michael Garval, Professor of French and Director of the interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. His research interests include celebrity, visual culture, and gastronomy. The author of ‘A Dream of Stone’: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture, and of Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is currently working on a new book project, Imagining the Celebrity Chef in Post-Revolutionary France.

The post Disgusting Truth: What Can Foul Food Reveal about Trump? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 9, 2017

Pandora: the original woman?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

John William Waterhouse, Pandora (1896)

In the beginning, there was – a man. Later, there was also a woman. That’s the basic plot of both the Judaeo-Christian and the ancient Greek creation stories, in which woman is a late arrival on the scene. In the first of these Mediterranean traditions, woman is made from man – specifically, from Adam’s rib (and by the way, men don’t have fewer ribs than women, even though I’ve been told by some Christians that they do). In the second, woman is made from mud.

Making Eve

Of course, it’s not quite that simple. Taking the Genesis creation story first, there are in fact two different accounts of creation in the first couple of chapters: the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible even inserts a sub-heading, ‘Another account of the creation‘. While the first version goes through all six days of creation one by one, culminating in humankind, the second version has the whole of creation made in a single day – ‘In the day that the Lord God made the earth and the heavens…’ In the first version, plants are on Day 3, but in the second version there are no plants yet because ‘there was no one to till the ground’ until after Adam had been made. Version 1, plants before people: version 2, people before plants.

In the first of these versions, God created:

humankind in his image,

in the image of God he created them,

male and female he created them (Genesis 1:27)

It’s only in the second account that we come to the more familiar story that God made a man out of the dust of the ground and then, later on in the creation process, made from this man’s rib the first woman, because ‘it is not good that the man should be alone’ (Genesis 2:18). In the first account, both sexes are equally in ‘the image of God’, while the second emphasizes the unity of their flesh as both origin and goal, ending with a man ‘clinging to his wife, and they become one flesh’.

Stories are told for a purpose. The first version feels like it is answering the question ‘How did God make the world?’ or perhaps ‘In what order did creation come into being?’ The second version gives the impression that it was designed to answer either ‘Why are there women?’ or ‘So why does a man leave his father and mother and live with his wife?’

Making Pandora

What about Pandora? Her story as well comes in two versions, both by the poet Hesiod who probably lived in around 750 BCE. In one of his poems, the Theogony, Hesiod’s purpose is to explain the origin of all the gods. Pandora is the combined effort of many gods, and she is labeled a kalon kakon, a ‘beautiful evil’. There’s no mention of opening a jar; Pandora is trouble enough on her own. While the feminine principle already existed in creation, now it is incarnated as a woman.

In the other version, in Works and Days, the focus is again on her creation, by all the gods: here, Hephaistos mixes earth with water, and gives her a voice and the shape of a young girl; Athene teaches her to weave; Aphrodite gives her desire but Hermes provides for her ‘the mind of a bitch’. Thanks, Hermes! She is given necklaces and a garland of flowers by the Graces, Persuasion and the Hours. Decked out like a bride – or, as some scholars have suggested, like an animal about to be sacrificed – she is sent to mortal men. Then, lifting the lid of a large storage jar she had been told not to open, Pandora lets out all the evils which are now a familiar part of human life.

Pandora and Eve

Pandora’s status is very different from that of Eve in the Biblical stories. In the first Genesis version, women were just part of the original creation: in the second Genesis version, the Lord God produced woman to solve the problem of man being alone. But Eve is a punishment. She is a pawn in a male world. She was manufactured by Zeus as one move in a complex game he is playing with the culture-hero Prometheus. Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to men. He thought he had deceived Zeus here, as he did earlier when he played a trick on Zeus in which he mixed up the meat and the fat in a sacrificed animal so that humans got the best parts. But Zeus is all-knowing, and really can’t be fooled. Pandora is his master-stroke, his trump card. Beautiful, irresistible, she hides both the ‘mind of a bitch’ and a ravenous appetite which keeps men at work in the fields to produce the food she needs.

In Genesis 3, a continuation of the version in which she is made from Adam’s rib, Eve has her Pandora-moment when she makes everything go wrong; she listens to the serpent who encourages her to pick the fruit of the forbidden tree. When we contrast her with Pandora, designed as a trap from day one, Eve looks a far more sympathetic character because she hasn’t been created with a deceptive nature. Pandora was programmed to cause chaos: Eve had a choice. Does that make Eve worse, or better? What do you think these stories show about those who created them?

Comparing these two sets of two myths enriches our understanding of the ancient world. We can see that Pandora isn’t exactly the ‘Greek Eve’ but, like her, she tells us something about how a group of people saw the role of women in their culture.

Helen King enjoys sharing ideas about the history of the body and of medicine, whether that means teaching school students on a ‘Roman Medicine’ themed day, lecturing surrounded by body parts in jars at the Bart’s Pathology Museum, or talking to heart surgeons at the Royal Galleries at Holyroodhouse. Her most recent book is The One-Sex Body on Trial: The Classical and Early Modern Evidence (Ashgate, 2013) and, as part of her commitment to distance learning, she has written a MOOC on ‘Health and Wellness in the Ancient World’.

Helen King enjoys sharing ideas about the history of the body and of medicine, whether that means teaching school students on a ‘Roman Medicine’ themed day, lecturing surrounded by body parts in jars at the Bart’s Pathology Museum, or talking to heart surgeons at the Royal Galleries at Holyroodhouse. Her most recent book is The One-Sex Body on Trial: The Classical and Early Modern Evidence (Ashgate, 2013) and, as part of her commitment to distance learning, she has written a MOOC on ‘Health and Wellness in the Ancient World’.

The post Pandora: the original woman? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 4, 2017

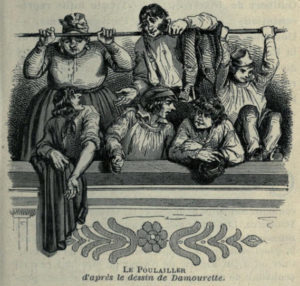

Noisy Ladies in the French Theater

By Lise Schreier (Guest Contributor)

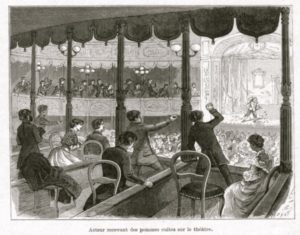

In June of 1816 Lady Morgan, the daughter of a famous Irish actor, hastily vacated her seat at the Comédie Française in a state of shock. “I had suffered so much from fear, agitation, heat, and noise,” she noted, “that the moment the curtain dropt [sic] I left the box […] to take some refreshments while the hurricane of the house still assailed our ears.” The tumult in the audience had been so great that she had not heard a word uttered on stage. People had hissed, shouted, clapped, jumped, stomped, and roared with laughter. She was forced to leave the premises amidst a “wild uproar” unlike any she had ever experienced before at the theater. Only after a restorative “ice and capillaire”––a trendy syrup made from fern leaves––did she manage to gather her wits.

Did Lady Morgan go to the theater on a particularly bad day? Not at all. For the French, such boisterousness was business as usual.

Indeed, playhouses were loud in nineteenth-century France. The director of La Force, a Parisian prison, boasted of not having to read theater reviews because he could tell how bad a play was by the number of combative youths brought to him after a premiere.

A rowdy audience throws apples.

All sorts of noises could be heard in performance halls, from the screams of factions throwing apples on stage and vowing to “turn the theater into a hospital,” to the bawling of infants, to the laborious mastication of men eating French fries in the nosebleed rows. Disruptions were to be expected on any given night, regardless of what kind of production was staged or what kind of public had gathered. A tragedy could cause as much pandemonium as a melodrama or a vaudeville play, for neither fashionable crowds nor popular audiences thought twice about causing a ruckus.

Women join in on the fun

Such unruliness was not only the work of restive men and overtired children. Working class women routinely sang, cried, sneezed, yawned and snored during a performance. And while in most public social realms, French ladies were expected to be silent, they too were allowed to make noise at the theater.

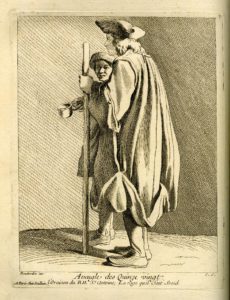

In fact, in France, generations of high society women brought to the theater an object whose sole purpose was to make noise: a whistle. These small instruments, made of silver or a much sought-after Dieppe ivory, and often adorned with a gold ring and a ribbon, tell us that unlike other shared spaces such as drawing rooms or ballrooms, where watching and being watched was the main concern, playhouses allowed even proper ladies to let loose.

In fact, in France, generations of high society women brought to the theater an object whose sole purpose was to make noise: a whistle. These small instruments, made of silver or a much sought-after Dieppe ivory, and often adorned with a gold ring and a ribbon, tell us that unlike other shared spaces such as drawing rooms or ballrooms, where watching and being watched was the main concern, playhouses allowed even proper ladies to let loose.

Whistling, it should be noted, was how French theater-goers booed actors off the stage. The practice was so common that there was an expression for it: “calling Azor.” According to popular lore, the father of a young actor became so distraught when the public whistled during his son’s performance that he unwittingly let his dog run onto the stage. A generous spirit managed to convince him that the audience members were not so much whistling at his son, as at Azor (a popular dog’s name at the time), whom they had noticed even before the dog’s escape. Comforted by the thought, the father began to whistle as well.

Nineteenth-century audiences called Azor high and low. The working class whistled with their fingers. Middle class troublemakers owned wooden whistles and used them with gusto. But only high society women could jeopardize an artist’s career with a luxury item.

Nineteenth-century audiences called Azor high and low. The working class whistled with their fingers. Middle class troublemakers owned wooden whistles and used them with gusto. But only high society women could jeopardize an artist’s career with a luxury item.

And use their whistles they did, to the horror of their male companions. The author of a handbook for theater lovers did not hide his scorn for such uncouth behavior, describing some spectators as self-declared magistrates of dramatic arts: “In certain provincial playhouses,” he wrote disdainfully, “it is not unusual to see women armed with a small silver or ivory whistle and call Azor two or three times.” Gentlemen were permitted to shout, howl with laughter, or box their neighbor’s ears in anger, but the thought of having ladies audibly participate in a public remonstrance was clearly unbearable. Such behavior was not sensible. Worse, it was not Parisian.

The fashionable, feminine whistle

The fashionable, feminine whistle

This did not stop women from using their whistles. These fine accessories helped them show that fashion, femininity, social standing and gleeful participation in public manifestations of displeasure could––and did––go hand in hand.  The elegant ivory effigies shown here, with their exquisite features, perfect hairdos and even a very fashion forward straw hat, demonstrated that ladies could make strident noises while remaining ladies.

The elegant ivory effigies shown here, with their exquisite features, perfect hairdos and even a very fashion forward straw hat, demonstrated that ladies could make strident noises while remaining ladies.

And so, all that men could do was develop coping strategies. When the public called Azor, artists had to endure it in their own way. The late nineteenth-century philologist Émile Gouget reported that the actor Domenico Cimarosa swore under his breath “like a pagan,” Niccolò Piccini sucked on candies, Giovanni Paisiello stuffed his nose with Spanish tobacco, and Gioachino Rossini got up and bowed deeply, which stopped the audience in its tracks.

One can only imagine what the ladies’ male companions did, for their part, when the female whistlers chimed in with their sounds. Surely they must have needed something stronger than fern syrup to recover.

Lise Schreier is currently completing Playthings of Empire, with the support of an American Philosophical Society Grant and a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. The book tells the story of African and Indian children used as gifts, pets, and fashion accessories during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Associate Professor of French at Fordham University and Associate Editor of Nineteenth-Century French Studies, she is also the author of Seul dans l’Orient Lointain: Les Voyages de Nerval et Du Camp and Gens de Couleur dans Trois Vaudevilles du Dix-Neuvième Siècle (forthcoming in February 2017).

Lise Schreier is currently completing Playthings of Empire, with the support of an American Philosophical Society Grant and a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. The book tells the story of African and Indian children used as gifts, pets, and fashion accessories during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Associate Professor of French at Fordham University and Associate Editor of Nineteenth-Century French Studies, she is also the author of Seul dans l’Orient Lointain: Les Voyages de Nerval et Du Camp and Gens de Couleur dans Trois Vaudevilles du Dix-Neuvième Siècle (forthcoming in February 2017).

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column on nineteenth-century material culture edited by Rachel Mesch. Read more of our posts here.

The post Noisy Ladies in the French Theater appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

Lady Jane Grey: ‘If her fortune had been as good, as was her bringing up …’

By Nicola Tallis (Guest Contributor)

The traditional tale of Lady Jane Grey’s life goes something like this: a young girl who was cruelly abused, both physically and mentally at the hands of her ambitious parents, forced into a marriage and a queenship that she did not seek, which culminated in disaster when she was executed at the age of seventeen. Thus, she became one of the Tudor era’s most tragic victims. Elements of this story are undoubtedly true, but to remember Jane in such a way is to do her a huge disservice.

In an age in which women were paid scant attention in surviving sources, Jane not only managed to find her voice and make herself heard, but also earned the respect and admiration of her contemporaries both in England and on the Continent. Three of her surviving letters, all addressed to the noted Protestant theologian Heinrich Bullinger, demonstrate her intellect and her enthusiasm for learning, as well as her increasing fervency for her faith. Addressing Bullinger as ‘the father of learning’, it is these letters that allow modern historians glimpses of Jane’s personality, revealing her to be a girl of the utmost intellect who was not afraid to share her thoughts and ideas. At a time when women were expected to be submissive and conform to the wishes of their husbands and fathers, such expression was extraordinary – even more so for a girl of such youth.

Jane’s impressions were shaped and developed by an integral part of her life: her education. She was fortunate enough to have been born into an era in which the education of women was becoming increasingly desirable, and her parents had spared no expense when it came to educating their eldest daughter. Furthermore, it was an opportunity that Jane grasped eagerly with both hands. She was exceptionally gifted when it came to learning, and took great pleasure in working towards the improvement of her mind. This did not go unnoticed by her contemporaries, many of whom took the time to remark on her intellect. The martyrologist John Foxe observed that Jane was ‘not only equal, but also superior’ in learning to her cousin Edward VI, whilst the Protestant John Banks declared that ‘in the seventeenth year of her age she excelled all oth er ladies.’ Foxe and Banks were not alone in their praise of Jane, and such comments demonstrate just how extraordinary Jane was, as well as revealing the deep impression that she made on her contemporaries.

er ladies.’ Foxe and Banks were not alone in their praise of Jane, and such comments demonstrate just how extraordinary Jane was, as well as revealing the deep impression that she made on her contemporaries.

Ultimately however, Jane’s true abilities and ambitions were never fully realised, and she died long before she was given the opportunity to achieve her full potential. As Foxe remarked, ‘If her fortune had been as good, as was her bringing up,’ there is no knowing what she may have been able to accomplish. Though Jane is remembered as a tragic pawn in the complex world of sixteenth-century politics, her recognition ought to lie elsewhere: as an exceptionally intelligent young woman who earned the respect and admiration of some of the most learned men in Europe.

Nicola Tallis is an English historical researcher and writer who is passionate about sixteenth-century history. Crown of Blood is her debut book, the result of five years of research on the Grey family.

The post Lady Jane Grey: ‘If her fortune had been as good, as was her bringing up …’ appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

January 2, 2017

Siegfried and the Dragon Legend Linked to Dinosaur Footprints?

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

A fearsome dragon was featured in medieval Scandinavian and Germanic legends about the hero Sigurd/Siegfried. The story is the centerpiece in the epic saga Niebelungenlied, in which the Siegfried kills Fafnir, who had been transformed into a hideous dragon by a powerful curse.

In the legend, Fafnir guarded a hoard of golden treasure. The dragon was so huge that the very ground shook when he walked. At Drachenfels (“Dragon Rock”), Konigswinter on the Rhine, a large statue of a typical dragon lurks near the ruins of a castle built on the summit of the hill in about 1150. A cave below was believed to be Fafnir’s lair.

According to the story, the hero Siegfried tracked the Dragon to his lair, by following a trail of the dragon’s enormous footprints sunk deep in the earth.

Notably, conspicuous fossil trackways of two types of massive dinosaurs are found in Germany. In 1941, the German paleontologist H. Kirchner speculated that observations of Triassic dinosaur tracks in sandstone near Siegfriedsburg in the Rhine Valley of western Germany might have been the inspiration for the legend about the dragon Fafnir’s footprints.

Since then, more dinosaur tracks have been analyzed by paleontologists in northern Europe. Immense fossilized footprints of a theropod dinosaur were recently found near Muenchehagen, Germany. Another long trackway left by a massive 30-ton Sauropod from 140 million years ago is embedded in a quarry at Rehburg-Loccum, near Hannover, Germany. Their magnitude–4 feet wide and 17 inches deep–would certainly lead anyone in antiquity or the Middle Ages to visualize a legendary dragon of dreadful size and shape.

Wagner’s famous Opera “Ring of the Neibelung” features Siegfried fighting a medieval-style dragon on stage. But in 2005, for the first time in opera history, the Lyric Opera of Chicago portrayed Fafnir as a frightening fossil monster, a kind of fantasy dinosaur skeleton. This was a way of acknowledging the idea that discoveries of remarkable fossils may have influenced images and tales of dragons in pre-Darwinian societies.

Adrien ne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Sc

ne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Sc ience, Stanford University, is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times (2011), Fossil Legends of the First Americans (2005), and The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, and The Amazons.

ience, Stanford University, is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times (2011), Fossil Legends of the First Americans (2005), and The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, and The Amazons.

The post Siegfried and the Dragon Legend Linked to Dinosaur Footprints? appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 31, 2016

Veuve Clicquot 1893: This One’s Really Vintage

By Tilar Mazzio (Guest Contributor)

The BBC reported this summer that the owner of a castle in Scotland discovered a bottle of unopened 1893 Veuve Clicquot champagne, the oldest known to exist. The lucky laird gave the bottle to the champagne house, where it is now on display as part of their historical exhibit.

And since much of the value in this special bottle is the fact that it was preserved unopened, chances are slim that this bubbly will ever find its way to a glass. But if it were poured, what would nineteenth-century champagne look and taste like? Veuve Clicquot champagne started using its trademark yellow label sometime in the mid-1860s, and, since it was used exclusively in the beginning to advertise a drier style of champagne to the English market, chances are the wine in this newly discovered bottle is brut champagne.

The term is a bit relative. Today, brut champagne is a dry wine. But, in the nineteenth century, folks drank their bubbly cold and sweet. An average bottle of champagne for the Russian market, for example, had as much as 300 grams of residual sugar—which is about twice what we find today in sweet dessert wines.

And since champagne then was almost always a dessert wine and not an aperitif, that makes sense. Most champagne at the time was made in the style known as blanc de noirs—a white wine make with a mixture of red and wine grapes. But, in fact, calling this bottle a white wine is probably something of a misnomer. Imbibers expected their champagne to have a rosy tinge, something a quick trip to the Oxford English Dictionary will confirm.

Portrait of Madame Clicquot and her great-granddaughter Anne de Mortemart-Rochechouart, future Duchesse d’Uzès.

There are early records showing that bubbly was often served as something resembling frozen slush, with that same viscosity that comes after a good bottle of vodka has been sitting the freezer for weeks. So we’d try it cold, something that’s not ideal for bubbles, of course. On the other hand, champagne then didn’t have the same sort of aggressive bubbles we find today in commercially produced sparkling wine either. The quality of the glassware wasn’t strong enough to withstand the intense pressure created by strongly carbonated wines.

We’d probably serve it in those shallow champagne goblets known as coupes and modeled, or so the legend goes, on the much-admired breasts of Madame de Pompadour. Until the Widow Clicquot discovered remuage—a system for efficiently clearing champagne of the yeasty debris that is a by-product of those bubbles—sparkling wine was often served in small, opaque V-shaped pilsner glasses, meant to disguise the floating sediment. By the middle of the century, champagne was reliably clear, and, although flutes existed, the preference was for coupes well into the mid-twentieth century.

Even if someone opens this newly discovered rarity, we won’t be among the lucky few to taste a drop. But what good historian doesn’t want to imagine this kind of first-hand research?

Tilar J. Mazzeo is the author of The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (HarperCollins 2008) and the travel guide to The Back-Lane Wineries of Sonoma (The Little Bookroom / Random House 2009). She teaches English at Colby College.

Tilar J. Mazzeo is the author of The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (HarperCollins 2008) and the travel guide to The Back-Lane Wineries of Sonoma (The Little Bookroom / Random House 2009). She teaches English at Colby College.

This post was originally published in November 2008.

The post Veuve Clicquot 1893: This One’s Really Vintage appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.

December 30, 2016

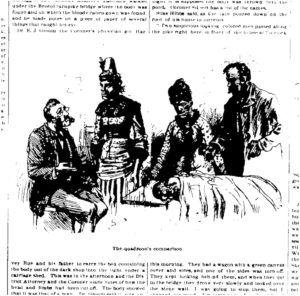

Black Women, Violence, and American History

Rogues’ Gallery Books (1887) Courtesy of the Philadelphia City Archives.

By Kali Nicole Gross (Guest Contributor)

In 1887, Hannah Mary Tabbs, a black Maryland migrant, found herself at the center of a gruesome murder in Philadelphia. The discovery of a headless, limbless, racially ambiguous torso just beyond the city limits had understandably unnerved both black and white residents. Though the case seemed doomed to go unsolved, given the inscrutable nature of the victim, two teams of investigators—in Eddington and Philadelphia—would eventually home in a black suspect. Hannah Mary Tabbs, as it turns out, had not only worked in Eddington and lived in Philadelphia but, as authorities would soon learn, she also carried on a passionate and volatile affair with the victim, a “mulatto” named Wakefield Gaines. Although the case is atypical in many respects, it nonetheless offers some critical, historical meditations on American violence.

As a black woman, Hannah Mary Tabbs existed at the complex intersection of race, gender, and sexuality, but her personal origins would place her at an equally complicated moment in history. Specifically, she was born during the 1850s, the time of enslavement, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland—a region notorious for a brutal slave-owning family. She also grew up in a state that was occupied during the nation’s bloody civil war. At war’s end, she was on the precipice of womanhood, a girl of approximately sixteen years of age, with a mulatto baby in tow. That she survived at all is itself something of a miracle; that she was not untouched by the period’s violence should come as no surprise.

“The quadroon’s comparison,” “Coon Chops,” National Police Gazette, March 5, 1887.

After she married and migrated north in the 1870s, Tabbs managed to secure good jobs as a cook in a number of white homes, where she worked without incident for nearly a decade; but the investigation into the Gaines homicide would unearth a fairly extensive record of brutality—acts she meted out in her home and also against others in the black community. Many black women of the time were vulnerable to victimization and had few avenues for legal redress. It seems that Tabbs not only used violence and intimidation to protect herself and navigate that difficult urban landscape but she also found ways to use brutality to create space in which to dominate those in her immediate orbit and to grant herself the illicit sexual pleasures that came along with her extramarital relationship with Gaines. Her methods and apparent motives are at once unsettling and enlightening. They speak to the ways that discrimination, violence, and trauma create victims and victimizers—and suggest that individuals can often occupy both identities.

Though cases like this are rare, figures like Hannah Mary Tabbs nonetheless offer an important vantage onto the extremities of black womanhood and its relationship to violence in American history.

Kali Nicole Gross is professor of African American Studies at Wesleyan University and author of Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880-1910, the newly released Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso: A Tale of Race, Sex, and Violence in America (OUP 2016), and co-author of the forthcoming book, A Black Woman’s History of the United States (Beacon 2018). Follow her on Twitter @KaliGrossPhD

Kali Nicole Gross is professor of African American Studies at Wesleyan University and author of Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880-1910, the newly released Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso: A Tale of Race, Sex, and Violence in America (OUP 2016), and co-author of the forthcoming book, A Black Woman’s History of the United States (Beacon 2018). Follow her on Twitter @KaliGrossPhD

The post Black Women, Violence, and American History appeared first on Wonders & Marvels.