Holly Tucker's Blog, page 10

November 7, 2016

The Metallic Ink of Herculaneum scrolls

By Keith Houston, Guest Contributor

In January 2015, scientists at the European Radiation Synchrotron Facility in Grenoble, France, announced that they had deciphered handwritten text from a series of papyrus scrolls excavated at the Roman town of Herculaneum by passing X-rays through the scrolls’ carbonized remains. Then, in March this year, another secret was revealed. Those same scrolls were discovered to have been written with distinctive metallic ink, once through to have been invented many hundreds of years later, and which boasted – or rather, whispered of – roots in ancient spycraft.

The disappearance of carbon ink

Since time immemorial Roman scribes had employed a system of hollow reed pens, homemade ink, and papyrus scrolls purchased according to length. The ink in which they dipped their pens was a mixture of water, gum arabic, and soot, just as it had been for the Egyptians and Greeks before them. Gum came from the acacia trees found in Asia Minor to the East; soot, on the other hand, could be scraped off burnt cooking utensils, ground down from cremated elephant bones, or prepared in a purpose-built furnace, depending on the motivation and the means of its maker. It was a simple recipe, and a flawed one: the distinguishing feature of carbon ink was that it could be washed off papyrus scrolls with nothing more than a moistened finger. (Martial, a Roman poet of the first century CE, wrote of sending out his books still wet so that discerning patrons could erase poems not to their liking.)

Sometime during the first century, however, things began to change. As the ERSF researchers discovered, scribes at Herculaneum were using a quite different kind of ink no later than 79 CE, when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius choked the life out of the town – an ink with metallic elements in its make-up that is opaque to X-rays. The days of carbon-based ink were numbered.

A new medium: metal ink

Until now, the received wisdom was that metal-based ink had become popular only during the third or fourth century CE, popularized by Christian scribes who copied and re-copied the Gospels and other important religious works. To make metallic ink, nutlike tree growths called galls were dried, crushed and infused in rainwater, wine, or beer, before being mixed with sulfate of iron or copper. The acidic gall liquor reacted with the metal sulfate as soon as the two were brought together to form an insoluble pigment that fixed itself on the page, and scribes learned to breathe into their ink jars to replace the air with unreactive carbon dioxide before stoppering them. For ancient writers, metallic ink was a quantum leap forward, as permanent on papyrus as it was on the new-fangled parchment becoming popular with scribes as far afield as Gaul and Britannia.

But the irony of metallic ink is that it may well have grown out of a need for subterfuge rather than brazen permanence. In the third century BCE, a Greek engineer named Philo wrote of what he called “sympathetic ink” made from tree galls and copper sulfate, but these familiar ingredients were to be brought together after their message had been written, not before. In Philo’s scheme, a would-be spy or illicit lover wrote on papyrus using a colorless infusion of crushed tree galls; on receipt, their correspondent washed that same papyrus with a solution of copper sulfa te to reveal its hidden message.

te to reveal its hidden message.

Work to decipher the Herculaneum scrolls is still ongoing, and we don’t yet know whether their singular metallic ink is a descendant of Philo’s recipe or something else entirely. But whatever we learn, our understanding of ancient writing practices has already been turned on its head. Metallic ink was used centuries earlier than previously thought, long before Christian monks and scribes turned their hands to it, in a Rome where citizens prayed to household shrines and where the wrath of Vulcan, god of the volcano, was still a thing to be feared.

Keith Houston is the founder of shadycharacters.co.uk. His latest book, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time, is available now from W.W. Norton & Co.

Eagle Huntress Discovered on Ancient Gold Ring

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

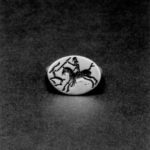

Eagle huntress on gold ring 425 BC Boston Museum of Fine Arts painting by Michele Angel

How long have women participated in the ancient nomad practice of eagle falconry? The question arose in fall 2016, with the release of “The Eagle Huntress,” a documentary film about a teenage Kazakh horsewoman training a golden eagle to hunt in Mongolia.

A striking piece of archaeological evidence for nomad horsewomen hunting with trained eagles in antiquity came to light only recently.

The artifact is an exquisite ancient gold ring made in about 425 BC, displayed in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The full significance of the hunting scene on the ring had eluded specialists’ understanding until a few years ago.

The ring shows a nomad horsewoman, identified in the museum text as an “Amazon.” Her hair and cloak are blown back, indicating the speed of the galloping horse. The woman carries a spear in her left hand and holds the reins in her right. The scene is so finely detailed that one can identify the species of deer–a spotted fallow buck with broad palmate antlers, common in Eurasia. The dog at her side is is a sight-hound similar to those used today by eagle hunters in Central Asia.

A large bird hovers in the top left above the deer. Art historians assumed the bird was merely a decoration. But in 2013, a series of spectacular photographs was published online and in international media, recording the victories of a young eagle huntress named Makpal Abdrazakova, who had been winning acclaim in eagle festivals and contests in Kazakhstan since 2010. Looking at these photographs of Makpal and other eagle huntresses and hunters led me to realize what was being depicted on the ancient gold ring. The bird above the fallow deer’s head is obviously an eagle with a hooked beak with spread wings and tail, about to attack the deer. The large bird was not random, as previously believed, but an integral part of the scene–it was the horsewoman’s other hunting companion, a trained golden eagle.

This naturalistic scene was identified as the earliest known image of a female eagle hunter in my book of 2014, The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World, with color plates 8 and 9, showing the ancient golden ring and Makpal Abdrazakova on her horse with her trained golden eagle in 2013.

The ring is compelling evidence that the unknown artist — perhaps not Greek but craftsman working in Anatolia or the Black Sea region — knew about or maybe even observed nomadic horsewomen of the steppes hunting game with trained eagles and sight-hounds.

A somewhat similar hunting scene but without a dog and eagle can be seen on a  bronze and silver alloy ring from the same date, late fifth century BC, in the Baltimore Walters Art Museum. That ring depicts a male hunter on horseback wearing a Scythian-style cap, brandishing a spear and chasing an antelope. The museum text suggests that the “ring belongs to a group made by local ‘barbarian’ Anatolian craftsmen in imitation of so-called Greco-Persian gems.”

bronze and silver alloy ring from the same date, late fifth century BC, in the Baltimore Walters Art Museum. That ring depicts a male hunter on horseback wearing a Scythian-style cap, brandishing a spear and chasing an antelope. The museum text suggests that the “ring belongs to a group made by local ‘barbarian’ Anatolian craftsmen in imitation of so-called Greco-Persian gems.”

For further information on the history of nomad women of the steppes participating in the ancient practice of eagle hunting and new generations of eagle huntresses, see https://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/Eag...

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

Who Keeps Women’s Secrets?

by Helen King (Regular Contributor)

By Ed Yourdon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

“Do you want to know a secret?”When I was at school, there were various other pupils who would pose this question in some corner of the playground at break times. Often, the secret turned out to be something I knew already, or something I didn’t find very interesting, but for these children knowledge was power, and the language of secrecy was intended to set up a special bond in which they would impart the secret to an audience which was then supposed to see itself as privileged. Secret codes, secret files, secret societies, conspiracy theories … for both children and adults, the secret still has power.

Questions remain for historians about who knew what, and who told what to whom, surrounding knowledge of the body, particularly the reproductive body, in the ancient Mediterranean. Who knew, or claimed to know, about how bodies worked? How could a physician gain access to the secret knowledge women were thought to possess about how their bodies worked, and to the secrets hidden within that body? The female body has long been regarded as a place of secrets, a theme taken up in the title of Katy Parks’ award-winning book, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (2006), which looked at dissection as one way for men to gain direct knowledge for themselves.

Women’s knowledge

In ancient Greek medicine, where dissection was rarely an option, we can find references to the knowledge women have and also to how men can gain this knowledge. Sometimes the knowledge thought to be held within the community of women, normally inaccessible to men, is described in a negative way, as when a writer says that women simply can’t be budged on whether it is possible for pregnancy to last even eleven months.

There are some fascinating moments in the Hippocratic medical texts – the treatises associated with the name of Hippocrates, and dating from the fifth century BCE onwards – which hint at the ways in which women’s secrets may have been passed on to men. One such occurs in the Hippocratic treatise Fleshes, where the “common prostitutes” are described as the male author’s source for the formation of the fetus. It is hard to tell, here, whether the medical writers really were talking to these women, or whether the claim by one to have done so is intended to raise the stakes, suggesting that the knowledge asserted by other medical writers is inferior because it is not based on such good sources. Another group, the akestrides, are named as those who can confirm, to anyone wanting to know, that a child can be born after spending only seven months in the womb. It interests me that the duration of pregnancy features prominently as something on which knowledge is sought; clearly, the accuracy of this knowledge matters, in terms of whether or not a child is the legitimate son of its supposed father!

Midwives or healers?

But who were the akestrides? From the feminine case used for the definite article, they were women, and Paul Potter translated the word as “the midwives who attend women who are giving birth”. But the term, not used anywhere else in the Hippocratic corpus, simply means “healers,” so perhaps “female physicians” would be a better translation here than “midwives”; indeed, the great nineteenth-century translator of the Hippocratic corpus, Emile Littré, translated as “the female healers who help women in childbed”.

Here, beneath these different modern interpretations of the same text, we can detect changing assumptions about ancient Greek women’s roles – midwife or physician? the more passive “attend” or the more active “help”? – as well as about the knowledge expected of the midwife. It seems odd to me that a nineteenth-century translator is willing to consider “female healers” while a modern translator instead presents them as “midwives”. In the ancient world of knowledge, were midwives both the source for physicians learning about the female body, and the people to whom women themselves went to learn about conception (and, perhaps, contraception)? Were they the controllers of secrets, and how would they use this position to their own benefit?

In early modern Europe, a powerful image of the midwife presented her as a keeper of secrets, but also as needing to tell untruths if these helped the woman whose labor she managed; the seventeenth-century midwife Elizabeth Cellier negotiated this line with particular skill. Medicine from the eighteenth century onwards tried to put male theoretical knowledge of the birthing process above the experience of midwives, suggesting that there were no more secrets here; however, many secrets of the female body, such as the processes of ovulation and menstruation, and the role of sex hormones, remained undiscovered until the early twentieth century.

Infuriatingly, our only access to midwives’ knowledge in the ancient world is through the writings of men: any suggestions on how we can reconstruct what they knew?

Helen King: In the last two years, Helen King’s activities have ranged from teaching school students on a ‘Roman Medicine’ themed day, to lecturing to medical students in the Czech Republic on the origins of medical terminology; and from a public lecture surrounded by body parts in jars at the Bart’s Pathology Museum, to another public lecture for a group of heart surgeons at the Royal Galleries at Holyroodhouse; and from face-to-face teaching at the University of Vienna as a visiting professor in women’s and gender studies, to writing distance learning material for the new Open University Classical Studies MA.

Women’s secrets

by Helen King (regular contributor)

By Ed Yourdon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

“Do you want to know a secret?”When I was at school, there were various other pupils who would pose this question in some corner of the playground at break times. Often, the secret turned out to be something I knew already, or something I didn’t find very interesting, but for these children knowledge was power, and the language of secrecy was intended to set up a special bond in which they would impart the secret to an audience which was then supposed to see itself as privileged. Secret codes, secret files, secret societies, conspiracy theories … for both children and adults, the secret still has power.

Questions remain for historians about who knew what, and who told what to whom, surrounding knowledge of the body, particularly the reproductive body, in the ancient Mediterranean. Who knew, or claimed to know, about how bodies worked? How could a physician gain access to the secret knowledge women were thought to possess about how their bodies worked, and to the secrets hidden within that body? The female body has long been regarded as a place of secrets, a theme taken up in the title of Katy Parks’ award-winning book, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (2006), which looked at dissection as one way for men to gain direct knowledge for themselves.

Women’s knowledge

In ancient Greek medicine, where dissection was rarely an option, we can find references to the knowledge women have and also to how men can gain this knowledge. Sometimes the knowledge thought to be held within the community of women, normally inaccessible to men, is described in a negative way, as when a writer says that women simply can’t be budged on whether it is possible for pregnancy to last even eleven months.

There are some fascinating moments in the Hippocratic medical texts – the treatises associated with the name of Hippocrates, and dating from the fifth century BCE onwards – which hint at the ways in which women’s secrets may have been passed on to men. One such occurs in the Hippocratic treatise Fleshes, where the “common prostitutes” are described as the male author’s source for the formation of the fetus. It is hard to tell, here, whether the medical writers really were talking to these women, or whether the claim by one to have done so is intended to raise the stakes, suggesting that the knowledge asserted by other medical writers is inferior because it is not based on such good sources. Another group, the akestrides, are named as those who can confirm, to anyone wanting to know, that a child can be born after spending only seven months in the womb. It interests me that the duration of pregnancy features prominently as something on which knowledge is sought; clearly, the accuracy of this knowledge matters, in terms of whether or not a child is the legitimate son of its supposed father!

Midwives or healers?

But who were the akestrides? From the feminine case used for the definite article, they were women, and Paul Potter translated the word as “the midwives who attend women who are giving birth”. But the term, not used anywhere else in the Hippocratic corpus, simply means “healers,” so perhaps “female physicians” would be a better translation here than “midwives”; indeed, the great nineteenth-century translator of the Hippocratic corpus, Emile Littré, translated as “the female healers who help women in childbed”.

Here, beneath these different modern interpretations of the same text, we can detect changing assumptions about ancient Greek women’s roles – midwife or physician? the more passive “attend” or the more active “help”? – as well as about the knowledge expected of the midwife. It seems odd to me that a nineteenth-century translator is willing to consider “female healers” while a modern translator instead presents them as “midwives”. In the ancient world of knowledge, were midwives both the source for physicians learning about the female body, and the people to whom women themselves went to learn about conception (and, perhaps, contraception)? Were they the controllers of secrets, and how would they use this position to their own benefit?

In early modern Europe, a powerful image of the midwife presented her as a keeper of secrets, but also as needing to tell untruths if these helped the woman whose labor she managed; the seventeenth-century midwife Elizabeth Cellier negotiated this line with particular skill. Medicine from the eighteenth century onwards tried to put male theoretical knowledge of the birthing process above the experience of midwives, suggesting that there were no more secrets here; however, many secrets of the female body, such as the processes of ovulation and menstruation, and the role of sex hormones, remained undiscovered until the early twentieth century.

Infuriatingly, our only access to midwives’ knowledge in the ancient world is through the writings of men: any suggestions on how we can reconstruct what they knew?

November 2, 2016

How the Guy with the Bump on his Head Changed our Lives Forever, or the Invention of the Department Store

by Rachel Mesch

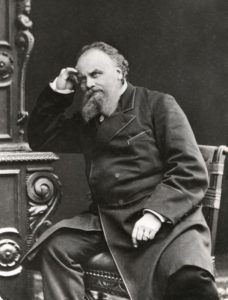

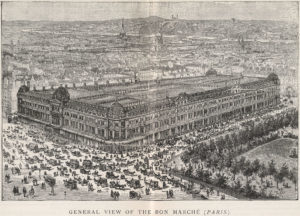

When counting up the various revolutions that shook nineteenth-century France,  we should not neglect the quiet one that took place in 1852 when the ambitious young merchant Aristide Boucicaut joined his shop with that of a colleague. It was the first step towards the invention of the department store, and with it, the explosion of consumer culture itself.

we should not neglect the quiet one that took place in 1852 when the ambitious young merchant Aristide Boucicaut joined his shop with that of a colleague. It was the first step towards the invention of the department store, and with it, the explosion of consumer culture itself.

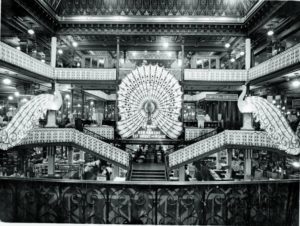

Aristide Boucicaut. You can make out his “bosse de commerce” just above the hand against his head.

Before Boucicaut thought to house as many different kinds of items as possible under one roof, French consumers would go to a specialized store for each purchase. But with the new one-stop shopping of Le Bon Marché—Boucicaut’s “grand magasin” (the French word for department store is literally “big store”)—consumers began to purchase not just what they had come to the store in search of, but what happened to catch their eye along the way. Less expensive items strategically—and aesthetically–placed towards the entrance drew people in; women’s fashions were hidden on upper floors, coaxing motivated shoppers to make their way through the labyrinthine layout, and invariably finding new must-have treasures along the way. The impulse purchase was born. Boucicaut bought in bulk and cut prices to thwart his competitors. Profit margins soared.

What’s more, rather than picking out fabrics and ordering clothing based on designs, for the first time customers could browse and touch the pieces, prêt-à-porter, ready to wear, trying them on so that they could then be altered to fit. No longer were buyers subject to prices that fluctuated at the whim of the seller. The tags were now posted, and the prix fixe meant one price for all.

Le Bon Marché in 1892

Emile Zola – who studied Boucicaut’s store as one might a new species—described all this as the “democratization of luxury.” And this aspect in itself was its own sort of revolution, really, for if everyone could buy the same dress, how was one to tell the difference between an upper bourgeois chic Parisienne and a high class courtesan? The department store went a long way towards effacing the visible differences in social classes, making it possible for anyone with enough cash on hand to dress the part they wished to play.

It would be hard to exaggerate the extent of this seismic shift in consumer culture. The brilliant Boucicaut took his store from a small mom and pop business to a staggering new form of commerce. Eventually employing nearly two thousand employees and raking in over seventy million francs a year, Le Bon Marché grew and grew. In the 1860s, Boucicaut hired Gustave Eiffel’s team (long before the tower was to bear his name) to build a giant new store—

1929 photo inside Le Bon Marché, courtesy of Marie Odile Radom

which had to be expanded even further midway—and which took nearly fifteen years to complete. It’s no wonder that Zola described the store as a machine, a cathedral, a monster with a life of its own. “A whole world was burgeoning there,” he writes, “in the echoing life between the high metal naves” (231).

1913 Christmas catalog

We can thank Boucicaut—whose bumpy forehead eventually became an idiom for business acumen in French—for pretty much every trick in the consumer culture book. Huge mark-downs to get you in the door? That was him. Prizes for kids to keep them distracted while the moms spent their money? Him too.

The white sale to encourage shoppers to spend money during the slow season? Advertising? Coupons? All of these started in Le Bon Marché. He also launched the first mail order catalog—issuing thousands of copies in multiple languages– so that you could literally shop from anywhere in the world.

The cupola of Le Printemps

One sign of Boucicaut’s success was his competition: in 1865, Jules Jaluzot opened Le Printemps, purposefully located in a still under-developed neighborhood near the Gare St Lazare. Jaluzot’s gorgeous structure– with its soaring stained glass cupola — soon invited enormous crowds to flow directly into Paris’s “cathedral of modern trade” (231) through the convenience of public transportation. “If he had known how,” wrote Zola in his fictionalized version, “he would have made the street run through his shop” (233). Matching Boucicaut’s ingenuity, Jaluzot launched the enduring end-of-season sale, and grasped the psychological potential of advertising: on the first day of spring, the store offered a bouquet of violets to those who visited—so that through this floral namesake, customers brought subliminal reminders of the store home with them along with their purchases.

The next time you flip through a catalogue, try on a dress, or come out of a store having bought something you did not go in there to purchase, you can think of the French man with the bump on his forehead and remember that –like so many aspects of modern consumer culture—it all started in nineteenth-century Paris.

Further reading:

Heidi Brevik-Zender, Mode and Modernity: Fashioning Space in Late Nineteenth-Century (University of Toronto Press, 2015).

Michael Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869-1920 (Princeton University Press, 2014).

Emile Zola, The Ladies’ Paradise (Au bonheur des dames, 1883). (Oxford World Classics, 2008).

October 31, 2016

Asia’s Inland Trade and the Europe’s Mercantile Empires

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

The official trading area of the Dutch East India Company, according to its charter

The way we learn the story in elementary school in the United States is that European trading companies sailed East in search of spices and other luxury goods. What those merchants took with them to trade is generally left unmentioned, perhaps because it makes it clear that Europe was a backwater in the global marketplace until well into the eighteenth century.

The truth is that in the early centuries of the Asian trade most European-made merchandise was a dud in the Asian marketplace. Some products, like mechanical clocks and toys, were too expensive for any but the wealthiest to purchase. Others, like heavy woolen cloth, were simply not useful or appealing. The only thing Europeans had that Asian were interested in was precious metal from the mines in Latin America.

The Portuguese, who controlled the trade routes from Europe to Asia for almost a hundred years, were content to pay silver for the luxury goods that reached their Indian stronghold at Goa. When the Dutch entered the spice trade in 1595, they did not have the luxury of paying for everything with hard currency. It was too expensive to simply trade with the Indies. Instead they learned to trade within the Indies: carrying goods from one Asian market to another as part of what they called the “inland trade” just as they carried goods from port to port along the coast of the Baltic Sea.

Merchants from all over Asia bought and sold goods at busy seaports along the Red Sea, on the coast of India, throughout the Indonesian archipelago, and in China and Japan. Islamic merchants in the Persian Gulf shipped raw cotton, coffee, dried fruits and nuts, and attar of roses across the Indian Ocean. Chinese merchants sold silks, tea, porcelain and zinc. India produced printed cotton textiles that were popular throughout Asia. South East Asia was the source for pepper, sandalwood, spices, and ivory.

Asian ships seldom sailed all the way from the Persian Gulf to China. Instead, an Arab ship would sail from Mokha to Surat and back. An Indian merchant would travel between Surat and Java. Chinese junks controlled the trade between Canton and Bantam. A chest of tea or a load of pepper would be bought and sold several times, and transported from port to port in several different ships.

Instead of concentrating on trade between two ports, the way most Asian merchants did, the Dutch East India Company (VOC)carried merchandise through the entire system, trading one type of goods for another, which was then used to buy a third. From one end of the chain to the other, Dutch traders handled more than one hundred Asian products, including raw silk, sandalwood, saltpeter, tin, opium, and cowrie shells. Each item was bought for a low price in the place where it was made and then sold for a higher price in another part of Asia in which it was in demand.

In order to make the most of this complicated series of trades, the VOC set up a network of permanent trading stations along the major trade routes in Asia–a process that often involved violence against local rulers and other European merchants. By 1785, the company had roughly 20,000 employees in twenty settlements spread across Asia, including company-owned spice plantations in Indonesia and walled warehouses in port cities in China, Japan , and India.

October 18, 2016

The Knights of the Forest Fought to Eliminate American Indians

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

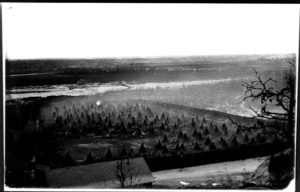

One morning in 1863, three U.S. Army companies guarded a path leading from a log jail in Mankato, Minn., to a steamboat docked at a landing in the Minnesota River. Hundreds of prisoners, most of them Dakota Indians, walked in chains to the steamboat as the soldiers kept a crowd of townspeople from molesting them. Jubilation filled the streets of Mankato. Once loaded with its human cargo, the steamboat headed downriver.

An internment camp for Dakota Indians on the Minnesota River below Fort Snelling

Over the next few weeks, many more steamboats conveyed thousands of Indians from Minnesota to desolate reservations in Dakota Territory and elsewhere. Frightened and outraged by the bloodshed of the U.S.-Dakota Conflict of 1862, some white citizens wanted the state to be free of Indians. “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state,” Governor Alexander Ramsey declared in September 1862. “The public safety imperatively requires it. Justice calls for it…. They must be regarded and treated as outlaws.” Ramsey and his supporters nearly achieved their wish, thanks in part to the vigilantism of a secret society headquartered in Mankato and known as the Knights of the Forest.

The U.S.-Dakota Conflict had set the state’s Dakota Indians — deeply aggrieved over late and spoiled government shipments of supplies, widespread hunger, and white encroachments upon their land — against soldiers and the rapidly growing settler population of southern Minnesota.

The end of hostilities didn’t leave white Minnesotans feeling more secure. All Indians grew suspect in their eyes. The Minnesota House of Representatives passed a resolution that demanded the deportation of all Native Americans from the state. Southern Minnesota’s Winnebago Indians, who occupied a reservation adjoining Mankato after forced relocations from other lands in Wisconsin and Iowa, became a special target of wrath. Many settlers believed the Winnebago had assisted the Dakota in the conflict, but the Winnebago denied it and a military commission’s investigation supported them.

To many of the region’s settlers, the Winnebago reservation tract contained something of much more interest than Indians. The Indians “were occupying and rendering useless 224 square miles of the best farming land in Blue Earth County,” later remembered C.A. Chapman, a local resident. He and like-minded friends decided to serve in a clandestine citizens’ organization, one dedicated to cleanse the area of its Indian presence.

Thus, in late 1862, was born the Knights of the Forest, which apparently appropriated its name from a passage in Sir Walter Scott’s novel Quentin Durward that described noble European warriors of the fifteenth century. (Ironically, the nineteenth-century artist George Catlin, who painted many scenes of Native American life, used the same phrase to idealize the Indians themselves.) Some people mistakenly believe that the Knights drew inspiration from the activities of the Ku Klux Klan in the South, but the KKK was not organized until 1867.

Like the Klan, however, the Knights made use of secrecy and elaborate rituals. “Great care was exercised in soliciting members to conceal the fact that such an organization existed from all not belonging,” the Mankato Daily Review revealed decades later. Surreptitious signs, handshakes, and passwords — not to mention armed guards — ensured that outsiders could not enter meetings. During C.A. Chapman’s initiation into the Knights, he pledged “to use every exertion and influence in my power to cause the removal of all tribes of Indians from the state of Minnesota.”

In the Mankato area today rumors still persist that armed members of the group patrolled the perimeter of the Winnebago reservation, and that they used intimidation and violence against Indians. We may never know the truth of these tales.

In the end, the U.S. Congress succumbed to the pressure of the Minnesota settlers. It passed laws mandating the removal of both the Dakota and the Winnebago from Minnesota. The government budgeted only $50,000 for each tribe’s transfer, so the moves proceeded callously and miserably.

Less than two weeks after the departure of the Dakota, 1,900 Winnebago involuntarily left their reservation lands and shipped out aboard two more steamships filled to capacity. Their white neighbors celebrated by waving flags and firing cannons. “Thus the last Indian left Blue Earth County and a new era dawned,” a local historian wrote. The townships of McPherson, Medo, Cedoria, Beauford, Rapidan, and Lyra, as well as sections of other settlements, arose on the former reservation.

In 1929, 66 years after these deportations, perhaps the last remaining Knight of the Forest died. He was John J. Porter, 91. In reporting his passing, The New York Times described the Knights only as “white settlers who had banded together against the hostile Indians.” Part of the story of the U.S.-Dakota Conflict had gone missing, and it has yet to fully reemerge.

This is adapted from an article that Jack El-Hai originally wrote for Minnesota Monthly.

Further reading:

Berg, Scott W. 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End. Vintage, 2013.

Lass, William E. “The Removal from Minnesota of the Sioux and Winnebago Indians.” Minnesota History, December 1963.

October 17, 2016

An Englishwoman Travels to America in an Election Year

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Frances Trollope

When Frances Trollope embarked with her three young children on a voyage to America in late 1827, she was on a business mission for her husband. She had been charged with investigating the possibilities for establishing a department store in Cincinnati, in a fanciful attempt to save the family’s collapsing finances. Three years later, the business enterprise had failed miserably and one of her children had become so ill that he had to be sent home to England. Frances was left to muse over her experiences and impressions of America. She did so in a book that she titled Domestic Manners of the Americans.

Her account was not enthusiastic. Her eccentric and exuberant husband had filled her with a picture of America as a land of opportunity, honesty, and natural, good-natured, optimistic, hardworking people. She would come away with the memory of “the bullying, struggling, crafty, enterprising, industrious, swaggering, drinking, boasting, money-getting Yankee, who cares not who was his grandfather, and meditates on nothing, past, present or to come, but his dollars, his produce, and his slaves.” Her memoir alternates between fascination with the amazing natural resources of the New World and bitter disappointment with the society of its inhabitants.

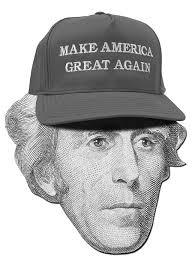

She covers a wide array of topics and impressions – from farming to dinner parties, schooling to church meetings, criminal justice to theatre, art, literature, fashion and food. A recurring commentary is on politics. Her first year in America was an election year, culminating in the inauguration of Andrew Jackson as president. When her book appeared in print, in 1832, it was the second term of Jackson’s electoral campaigning. Although she professes to have come to America with an open mind to the advantages of democracy, she was not impressed by American-style campaigning. From her initial boat ride up the Mississippi, when she witnessed a fight between two military officers, one pro-Adams and one pro-Jackson, she was struck by our crude and “incessant electioneering”. Her impression of cities is that political campaigning takes precedence over all other forms of management, including routine maintenance of roads and buildings. Americans love to argue politics, it seems to her, but she has difficulty hearing substantive reasons for supporting new candidates who are put forward. “Adams was out-voted for no other reason,” she writes, “than for the principle of ‘change’. ’Jackson forever!’ was, therefore, screamed from the majority of mouths, both drunk and sober, till he was elected.”

She covers a wide array of topics and impressions – from farming to dinner parties, schooling to church meetings, criminal justice to theatre, art, literature, fashion and food. A recurring commentary is on politics. Her first year in America was an election year, culminating in the inauguration of Andrew Jackson as president. When her book appeared in print, in 1832, it was the second term of Jackson’s electoral campaigning. Although she professes to have come to America with an open mind to the advantages of democracy, she was not impressed by American-style campaigning. From her initial boat ride up the Mississippi, when she witnessed a fight between two military officers, one pro-Adams and one pro-Jackson, she was struck by our crude and “incessant electioneering”. Her impression of cities is that political campaigning takes precedence over all other forms of management, including routine maintenance of roads and buildings. Americans love to argue politics, it seems to her, but she has difficulty hearing substantive reasons for supporting new candidates who are put forward. “Adams was out-voted for no other reason,” she writes, “than for the principle of ‘change’. ’Jackson forever!’ was, therefore, screamed from the majority of mouths, both drunk and sober, till he was elected.”

Caricature accompanying early press reviews of ‘Domestic Manners’

Not surprisingly, Frances Trollope’s travel account was not well reviewed in America. But it was a bestseller on both sides of the ocean. It was to launch her career as a writer. Her caustic analysis of social hypocrisy and shallow pride surely also influenced her son Anthony, whose writing would become famous for exhibiting similar talents. One American who did admire her was Mark Twain, who wrote:

“Of all the tourists I like Dame Trollope best, she found a ‘civilization’ here which you, reader, could not have endured; and which you would not have regarded as civilization at all. Mrs. Trollope spoke of this civilization in plain terms — plain and unsugared, but honest and without malice, and without hate … She was merely telling the truth and this indignant nation knew it. She was painting a state of things which did not disappear at once. It lasted to well along in my youth, and I remember it.”

Today’s readers, too, might well find that in this election year, Frances Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans still has many moments that ring true!

October 14, 2016

Eating What We Are, Seem, Overcome, and Dream

Iron Chef host Takeshi Kaga

By Thomas Parker, regular contributor

Iron Chef host Takeshi Kaga, who was more than a little enamored with the French nineteenth-century food writer Brillat-Savarin, is known to have re-popularized the latter’s famous statement “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

In his nineteenth-century Physiology of Taste, Brillat-Savarin associated the act of eating with the most common verb of the language: être (to be). Eating transformed the eater, he claimed, as the power of nature held in food shaped through the art and science of cuisine not only sustains us, but actually shapes who we are. Brillat-Savarin, who was both a chemist and a physician by training, sounded a call to arms to chefs and eaters alike to combine ingredients, science, and taste for refined healthy eating and good living.

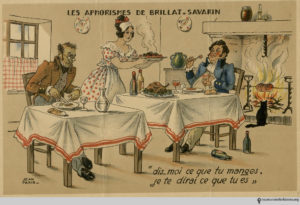

One of many of Brillat-Savarin’s aphorisms

One hundred and fifty years earlier, during Louis XIV’s reign in the seventeenth century, circumstances were appreciably different: food was much less associated with being than seeming. In a world of shifting social hierarchies, where rich bourgeois who weren’t born into aristocracy could buy noble titles, power was derived from merely appearing to be closely associated with the king and the splendor of Versailles. According to the prevailing wisdom of the time, it was more important to “paraître” (seem) than “être.”

Hippocratic and Galenic theories of medicine based on humors held over from the Renaissance encouraged this trend by suggesting that people with pure and delicate constitutions should gravitate toward foods with those same qualities. The connoisseur (usually self-pronounced) abided, eating with distinction and making a show of being able to discern flavors and foods that those with less pure constitutions would ignore. Instead of “you are what you eat,” the elegant proclaimed that you should “eat what you are.” One favorite for such aesthetes was white river veal from Normandy. Another was the Champagne of the town of Ay, known for its gustatory delicateness and ethereal purity. Using these foods and others, eaters attempted to perform class at the table, climbing the social ladder to achieve status in a world where seeming trumped being.

Veal from Normandy remains a specialty today

Since the time of Louis XIV and Brillat-Savarin, seeming and being have both remained relevant and evolved as the act of eating takes on new meanings in both France and the United States. To take one example, the famous physician and Harvard professor Leon Kass reversed Brillat-Savarin’s dictum in recent years. For Kass, human beings are at the top of the food chain and exert their dominance over the natural world at the table. We are not what we eat, but rather what we eat becomes us as we break it down and transform it into our bodies. In so doing, humans demonstrate their physical and symbolical dominance over the natural world, overcoming it in an experience repeated thrice daily.

This antagonistic relationship with food is rich with significance that arises in other contexts. Anthropologists have noted, for example, that culinary tourism contains elements that go beyond both sustenance and satisfying intellectual curiosity about foreign cultures to extend into paradigms of domination. We symbolically cannibalize the places and peoples we encounter by ingesting their wares. The stranger and more challenging their foods are, the more triumphant we feel when we imbibe them at the table.

A final relationship of note is more about dreaming than overcoming, seeming or being. Writing about the current popular trend of snout-to-tail eating, anthropologist Brad Weiss conveys that these whole-animal eating occasions are as much holistic as “wholistic” oriented. Eaters used to eat “high on the hog,” seeking out meat such as tenderloin, that was easier to disassociate from the animal. This allowed them to separate themselves from the animal world and elide the brutality of the carnivorous act because uniform nondescript pieces of meat packaged in shrink wrap under fluorescent supermarket lights no longer resemble the animal they come from.

Snout-to-tail eaters seek the opposite: in an act somewhat reminiscent of sacrificial rituel, they try to appropriate the animal, consuming the conspicuous innards and organs to remind themselves they are interacting with a being that once lived. In doing so, they are not looking to dominate nature, rather to reconnect with the idealistic life and free-range pastoral experience they imagine the animal to have lived. In eating, they are dreaming of leaving behind a humdrum, exhausted planet and a food system driven by markets, machines, and industrialized anonymity to find an identity in a perfect, green world. They no longer use food to know what they are, but to escape from what they’ve become.

October 10, 2016

Period pains – have women always suffered from menstrual cramps?

By Helen King (regular contributor)

A recent YouGov survey of 1000 British women showed that the majority had period pain, and 52% had found it affected their ability to work. John Guillebaud, a professor of reproductive health at University College London, suggested that the level of pain is almost as bad as a heart attack. Have women always suffered pain? This early twentieth-century advertisement for ‘Hall’s Coca Wine‘ is one of many types of evidence suggesting that they did; the tonic is effective for a range of conditions including ‘sickness, so common to ladies‘, a form of shorthand for menstruation and its associated pain.

Pain, like everything else – including menstruation itself – has a history. However, pain is very difficult to measure – there isn’t a ‘pain thermometer’, which is why patient questionnaires work on ‘is it better or worse than it was?’ rather than trying to compare one individual with another. If you rate your pain now as ‘8’, what matters isn’t whether your ‘8’ is the same as someone else’s, but whether next week you’ll put it above or below that personal baseline.

Labor pain

Women’s bodies have particular pains which men can’t experience: labor pains and period pains. In the eighteenth century, the obstetrician William Osborn wrote of ‘the calamitous condition of the [female] Sex, who at all times of parturition, are exposed to the severest bodily pain’. We have records of women’s comments on the level of pain experienced while giving birth, including those transmitted to us by male physicians; nineteenth-century women used words like ‘grinding’, ‘cutting’ and ‘sawing’ to describe what it felt like. In the mid-nineteenth century, in a lecture on the role of ether in childbirth, William Tyler Smith expressed the view that ‘No human suffering, perhaps, exceeds in intensity the piercing agonies of child-bearing’.

However, pain was seen as a necessary part of the process with some men even suggesting that the pain should be encouraged, because crying out in agony took some of the pressure off the womb. And, notoriously, as late as the nineteenth century some considered that labor pains were part of God’s purpose, reminding people of the ‘curse of Eve’ for offering Adam the apple in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:16-17). Those physicians promoting pain relief countered these Bible verses with others, such as James 4:17, ‘Therefore to him that knoweth to do good and doeth it not, to him it is a Sin’, which Sir James Young Simpson – pioneer of chloroform in childbirth – put on the title page of his 1847 Answer to the Religious Objections.

There are interesting questions here about whether the expectation of extreme pain was based on the fact that, by definition, medical practitioners saw those for whom things were not progressing normally. Some male writers went the other way and idealized menstruation; for example, Granville Stanley Hall, who in 1904 wrote that ‘The flow itself has been a pleasure and the end of it is a slight shock’!

Menstrual cramps

Questions about medical practitioners’ expectations apply even more to period pains. Simpson considered that these too should be treated, recommending blood-letting, warm baths and fomentations, enemas and sedatives – the latter including opium – as well as treatment between the periods to relieve any underlying inflammation or congestion. Different theories as to what caused the pain existed; was it due to the blood being ‘too thick’, to an obstruction, or to the veins which send the blood into the womb being stretched by the sheer quantity?

Here, too, women’s voices can be heard even in male-authored texts. In her book Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Woman’s Lives 1540-1714, Dr Sara Read noted a passage in Helkiah Crooke’s Microcosmographia (1615)

Between the kidneys and the womb the consent is evident in the torments and pains in the loins which women and maids have in or about the time of their courses. In so much as some have told me they had at least bear a child as endure that pain; and myself have seen some to my thinking by their deportment; in as great extremity in the one as in the other.

This explains why pain can be felt in other parts of the body; there is ‘consent’ or ‘sympathy’ between the organs. One way out of experiencing period pain was to get pregnant before your first period, and this was thought to be good for the baby as well: The English Midwife (1682) states that ‘if a virgin conceive before her first flowers [a traditional word for periods], it proves lusty and perfect child’.

After women’s roles started to change following the First World War, and in the popular literature of my mother’s day, the expectation of pain was played down in favor of the image of the girl who simply needs to ‘take things a little easier during those days’, the phrasing of a 1930 booklet for girls, Mary P. Callender’s Marjorie May’s Twelfth Birthday (a marketing device for Kotex pads). A similar message is promoted today, for example in the information campaign linked to the marketing of one brand of sanitary towel, which mentions cramps, tiredness and backache but emphasizes ‘stretches’ and ‘a positive mindset’.

And in the fifth-century BCE…?

It’s harder to tell what expectations were if we go even further back in time. In the Hippocratic corpus, the treatise on the diseases of young girls describes the first period as a difficult time but, in the alarming list of symptoms, pain as such does not feature. The ancient Greeks believed that the blood needed to make a passage through the veins to the womb, causing pain, but we could read the texts as suggesting that this process was expected to become easier – and therefore less painful – as the girl grew older. Giving birth was seen as a cure for period pains because it ‘opened up’ the body even more.

But, of course, ancient Greek women weren’t in the modern workplace! Elite women could simply let their slaves and servants get on with their jobs. Poor women would still have to collect water, do housework or go to the market.

For women from the late nineteenth century onwards, including those today, who’ve wanted to be taken seriously in the workplace, it’s important to play down period pains; we need to show that women shouldn’t be excluded from various roles in society simply because they are women. It may be significant here that one of the first women physicians, Mary Putnam Jacobi, argued in her The Question of Rest During Menstruation (1877) that normal women didn’t need to rest during menstruation. But I do wonder whether this view may have led to what has turned out to be an unhelpful denial of the reality of period pains.

Periods hurt in the past, too; maybe what’s new isn’t the pain, but a greater willingness to admit to suffering it. Mary Putnam Jacobi urged employers to allow women to rest during their periods if necessary: and that’s precisely what some women are suggesting today.

To find out more:

Helen King, Midwifery, Obstetrics and the Rise of Gynaecology (2007)

Sara Read, Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Woman’s Lives 1540-1714 (2015)

![By Ed Yourdon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1478610199i/21089452.jpg)