Holly Tucker's Blog, page 14

June 20, 2016

How Henri Matisse Sought Renewal in Tahiti and Found it in America

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

One of the most curious and unexpected influences in the career of Henri Matisse was his encounter with the American art collector Albert C. Barnes. In 1929, looking for new ideas at a moment in his life when the artist was feeling old and uninspired (he was 60), he decided to take a trip to Tahiti. His route took him across North America, where at first he was so enchanted that he almost didn’t complete the voyage. Everything he had been hoping to find in the South Seas – a vital environment bathed in simplicity, energy, light – he felt he was already encountering in America. “ The first time I saw New York,” he wrote later, “this gold and black block in the night, reflected in the water, I was in complete ecstasy.” What was to be a prolonged stay in the South Seas ended up as nearly three months in the United States, followed by just two months in Tahiti. Soon after his return to France, he made another trip to New York and decided to visit the collection of Albert Barnes outside of Philadelphia. Barnes owned more Matisse paintings than any other collector in the world. The artist wanted to look with fresh eyes at his own work, and contemplate how it was being presented to American viewers.

Matisse viewing his paintings at the Barnes gallery

Barnes was a cantankerous and eccentric collector. He had amassed a fortune in pharmaceuticals and was building one of the greatest personal collections of art in America, but he didn’t care for the world of art critics and he detested museums. He arranged the works on the walls of his foundation without regard for strict divisions by time period or painter and with no accompanying written explanations that would detract from viewing the paintings themselves. The Philadelphia elite shunned him (he was a butcher’s son) and he enjoyed insulting them back by inviting mostly ‘ordinary people’ to see his collection while denying the requests of celebrities, critics, and scholars. But when he heard that Matisse wanted to visit, he eagerly opened his door (though he refused admission to Matisse’s hosts from the Carnegie Institute). The two men hit it off. Matisse came away with a commission to produce a new mural for Barnes, to fill a space in the main gallery.

When he had looked for inspiration in the landscape and simplicity of Tahiti, Matisse would later say he had only found “lethargy” there. But in the peculiar style of the Barnes Foundation collection, Matisse found himself energized, and eager to participate in the ideas of this man who believed that art could be made fundamental to the lives of ordinary people without constant recourse to experts and museums set up like “cathedrals”, “temples”, or “tombs”, Matisse’s characterization of most museums. Matisse wrote in his diary that the Barnes Foundation was “the only sane place” he had seen for exhibiting paintings. He admired the well-lit, “complete frankness” of the presentation and declared that the paintings were “exhibited in a spirit very beneficial for the training of American artists.” He delayed his return to France in order to have more conversations with Barnes and develop his ideas for the new mural.

Matisse drawing sketches for his mural with a bamboo stick

In the ensuing months the artist and collector had more meetings, in both Paris and Philadelphia. Matisse made a template for the mural and he wrote to his wife that he felt he had made “great progress in terms of clarity of mind.” He was thrilled to be working on a piece that would be displayed in a way that would blend with the architecture of the gallery and also seem to be part of the greenery outside, as viewed through large windows below the mural.

But the mural would become a much more complicated and challenging task than either Barnes or Matisse had anticipated. The whole project was almost abandoned altogether after Matisse discovered, to his horror, that he had made a miscalculation in the measurements of the space his work was designed to fill. His “enormous mistake,” as Barnes termed it in a telegram, forced the artist to start over again on new canvases. Tensions developed. Barnes commented to Matisse’s son that the project was beginning to look like “the greatest tragedy of his life.” Finally, after more meetings between artist and collector on both sides of the ocean, in 1933 Matisse made the transatlantic crossing to personally install his finished canvases. He was worn out. He insisted on nailing the first canvas to the stretcher himself, and then promptly collapsed from stress and exhaustion. Doctors were called in and he was ordered to rest. Three days later, the mural installation was complete and Matisse was ecstatic: “When I saw the canvas put in place,” he wrote a friend, “it was detached from me and became part of the building, and I completely forgot the past, it became like a living thing. It was like a real birth in which the mother becomes detached from the past pain.”

Finally, after more meetings between artist and collector on both sides of the ocean, in 1933 Matisse made the transatlantic crossing to personally install his finished canvases. He was worn out. He insisted on nailing the first canvas to the stretcher himself, and then promptly collapsed from stress and exhaustion. Doctors were called in and he was ordered to rest. Three days later, the mural installation was complete and Matisse was ecstatic: “When I saw the canvas put in place,” he wrote a friend, “it was detached from me and became part of the building, and I completely forgot the past, it became like a living thing. It was like a real birth in which the mother becomes detached from the past pain.”

It would be his last voyage to America. But he would forever consider the Barnes mural project to be the one that enabled him to “go back to the source,” as he put it, and embrace a fundamental simplicity of design and purity of expression.

For further reading: Matisse: The Dance, by Jack Flam (Washington, D.C., 1993)

June 15, 2016

Museum Mysteries: Questioning an Evocative Image of Madame Curie

By Jeffrey Mifflin

Photograph by N.M. Jeannero, Pittsburgh Sun, 1921

Until recently, a vintage photograph in an old frame at the Massachusetts General Hospital Archives bore the caption, “Pierre Curie and Marie Curie Visiting America, ca. 1903.” The caption caught my attention and aroused my suspicions when I unframed the picture to facilitate its reproduction. Wasn’t Marie’s first visit to the United States much later? And hadn’t Pierre’s head been tragically crushed beneath the wheel of a horse-drawn vehicle long before then? Library sleuthing furnished the correct place and date for the photograph, provided background details, and explained some (but not all) of the intriguing circumstances surrounding the image, which originally hung in Mass General’s radiology department.

The discovery of radioactivity, a landmark in the history of science, earned Marie Curie, her husband, Pierre Curie, and Henri Becquerel the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. In the course of her research Marie discovered the elements polonium and radium. Radium is a radioactive decay product of uranium; both elements are found in uraninite (a mineral formerly known as “pitchblende”). The extraction of radium was an extremely laborious process.

Over the years Marie Curie gave away bits of radium on numerous occasions so that cancer patients could be treated. But by 1920 she was without means to acquire more of the difficult-to-obtain substance. An American newspaper woman, Mrs. W. B. Meloney, interviewed Curie at her Paris laboratory and learned that what she wanted most was more radium to continue her research. The cost of one gram of radium in 1920 was $100,000. Meloney raised the prodigious sum in less than a year, primarily through small donations and with the help of many American women. On May 3, 1921, the Marie Curie Radium Fund Committee awarded a contract to the Standard Chemical Company of Pittsburgh to extract a gram of radium.

Curie embarked for the United States to accept the gift, arriving in New York City (amid much fanfare) in May 1921 aboard the RMS Olympic with her daughters, Irène and Ève. She was in her early fifties, and it was her first trans-Atlantic trip. Her visit to the Canonsburg Plant of Standard Chemical that May was documented by a number of photographs. The image seen here shows her talking with two men, who seem to be escorting her around the industrial facility. They are presumably scientists or managers—not Pierre Curie, as the original caption indicated—working for the company.

The signal event of the American trip came when Curie was honored at the White House on May 20, 1921. President Warren G. Harding handed her the newly extracted radium (contained in a vial in a lead-lined mahogany box) during a ceremony before a group of admiring dignitaries. In a speech following the radium presentation, Harding welcomed Madame Curie on behalf of the American people: “As a nation whose womanhood has been exalted to fullest participation in citizenship, we are proud to honor in you a woman whose work has earned universal acclaim and attested woman’s equality in every intellectual and spiritual activity. . . . We greet you as foremost among scientists in the age of science. . . .”

Historical research revealed correctable errors in the original caption. But one lingering mystery remains. Why does the renowned guest have such an acerbic look on her face? Did she recoil from the intrusion of pesky photographers? Was she disturbed by some incident outside the camera’s field of vision? Or had too much exposure to radioactivity (a word she coined) already affected her health and disposition?

Jeffrey Mifflin is the archivist of Massachusetts General Hospital.

June 14, 2016

Toni Stone: The First Woman in Men’s Professional Baseball

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Most American girls who played youth baseball in the 1930s and ’40s—and there weren’t many—eventually dropped the game for marriage or jobs considered suitable for young women. Not Toni Stone, however. She became one of the sport’s great trailblazers: the first woman to play professional baseball in a men’s league.

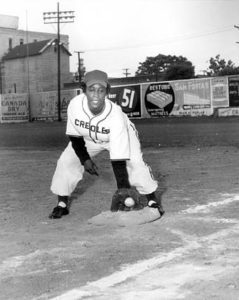

Toni Stone during one of her seasons with the New Orleans Creoles.

Born in 1921 in West Virginia, Stone soon moved with her family to St. Paul, Minnesota. Baseball attracted her almost immediately. Little League baseball barred girls, but a neighborhood priest bought her a uniform that enabled her to join a Catholic youth league. As a teen, Stone was talented enough to draw the attention of Gabby Street, a former big-league manager who had won the World Series with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1931 and established a baseball school in St. Paul. Stone honed her skills with the Twin Cities Colored Giants, a semipro African American team that played on weekends. In addition, she sometimes joined other Negro teams that took to the road in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

During World War II, Stone joined her sister in California’s Bay Area. With less than a dollar in her pocket and no clue where to find her sibling, she spent several nights sleeping in a bus station before meeting Al Love and Lena Morrell, owners of a bar in the Fillmore District, the center of San Francisco’s black community. They set Stone up with food and housing, and Love even helped her win a spot on an American Legion baseball team, making her perhaps the first black woman anywhere to play Legion ball.

By the late 1940s, Stone stood 5’7 “and weighed 146 pounds. She threw hard and was highly skilled in baseballs fundamentals. She could have easily earned a place in the All American Girls Professional Baseball League (dramatized in the movie A League of Her Own), but it declared only white women eligible for play. Instead, she joined the San Francisco Sea Lions of the West Coast Negro League, a men’s team that barnstormed the region. She batted .280 and made the league’s all-star team.

In 1949, Stone signed with the New Orleans Creoles, a prominent team in Negro League baseball. With New Orleans, Stone earned $300 a month and played regularly at second base. She remained with the Creoles for two years, batting .265 during her final season.

In achievement and distance, she had traveled a long way from the ball fields of St. Paul. “A woman has her dreams, too,” Stone explained to one of her Creoles teammates. “When you finish high school, they tell a boy to go out and see the world. What do they tell a girl? They tell her to go next door and marry the boy that her family’s picked out for her. It wasn’t right.”

After three years with the Creoles and one season with the Indianapolis Clowns, Stone moved to the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs, once the team of Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson, was one of the Negro League’s best franchises. Monarchs manager Buck O’Neil played her infrequently, however, and Stone decided to retire from baseball at the end of that season.

After Stone cut loose from professional baseball, she and her husband settled in Oakland, California, where Stone worked as a nurse. Stone managed to continue playing American Legion recreational baseball until she was 62 years old.

Over time, Stone and her old Negro League teammates faded from public memory. But when interest in African American players reignited during the late 1980s and ’90s, Stone was pleased to relive her role as a trailblazer. In 1990, St. Paul named a day in her honor, and the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame inducted her in 1993.

In 1996 she died at age 75 in a nursing home in Alameda, California, following a stroke.

Further reading:

Ackmann, Martha. Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League. Lawrence Hill Books, 2010.

Gregorich, Barbara. Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball. Harcourt Brace and Company, 1993.

Risk-Taking and the Maintenance of a Hardy Species

By Kayt Sukel (Guest Contributor)

In 1871, famed naturalist Charles Darwin published The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, the follow-up to his famous (and highly debated) book, On the Origin of Species. In The Descent of Man, Darwin extended his thoughts on evolutionary biology, gleaned from his observations and adventures, to the evolution of the human thought and behavior—and introduced a new theory of selection, related to natural selection, based on an animal’s sexual characteristics and features.

This so-called sexual selection, he argued, rises from female choice for mates—and male competition to receive that choice. Darwin argued that, since females only have limited reproductive opportunities, it pays for them to be choosy when selecting a mate. By waiting for a good catch, so to speak, females then have a shot at the hardiest possible offspring. Males, then, have to compete to stand out and command that potential mate’s attention in order to get the opportunity to make hay. Throughout the animal kingdom, Darwin described different species where males find ways to stand out—visually or behaviorally—in order to impress the girl and, thus, propagate his genes on down the line.

This so-called sexual selection, he argued, rises from female choice for mates—and male competition to receive that choice. Darwin argued that, since females only have limited reproductive opportunities, it pays for them to be choosy when selecting a mate. By waiting for a good catch, so to speak, females then have a shot at the hardiest possible offspring. Males, then, have to compete to stand out and command that potential mate’s attention in order to get the opportunity to make hay. Throughout the animal kingdom, Darwin described different species where males find ways to stand out—visually or behaviorally—in order to impress the girl and, thus, propagate his genes on down the line.

In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, he writes:

“When the sexes differ in colour or in other ornaments, the males with rare exceptions are the most highly decorated, either permanently or temporarily during the breeding-season. They sedulously display their various ornaments, exert their voices, and perform strange antics in the presence of the females. Even well-armed males, who, it might have been thought, would have altogether depended for success on the law of battle, are in most cases highly ornamented; and their ornaments have been acquired at the expense of some loss of power. In other cases ornaments have been acquired, at the cost of increased risk from birds and beasts of prey…What then are we to conclude from these facts and considerations? Does the male parade his charms with so much pomp and rivalry for no purpose?”

Why would a male pursue such risky business, to “sedulously display” such ornaments or perform such “strange antics”? The answer was simple: to prove his biological fitness—and, more importantly, stand out for a potential mate’s choice. Darwin believed such selective forces also worked upon us humans. In fact, in a letter to noted evolutionary biologist and colleague Alfred Russel Wallace, Darwin likened the length of peacock’s tail to a man’s whiskers.

“A girl sees a handsome man & without observing whether his nose or whiskers are the tenth of an inch longer or shorter than in some other man, admires his appearance & says she will marry him,” he wrote. “So I suppose with the pea-hen; & the tail has been increased in length merely by on the whole presenting a more gorgeous appearance.”

And did he see those “strange antics” seen in birds also playing a role in human mating rituals? Darwin certainly thought so. His thoughts on sexual selection led him to argue that men often won women through heroic deeds—as well as economic prowess and wealth. And Justin Garcia, an evolutionary biologist at the Kinsey Institute, says that such ideas stand up today, even in the wake of pioneering genetic research into the evolution of mating behavior and reproduction. Modern days still offer us plenty of examples where standing out by taking risks helps to command female choice, ultimately facilitating the creation of hardy offspring that will not only survive but, hopefully, thrive in life.

“We often talk about risk-taking as if it is some kind of pathology. And it can be related to pathological behavior in people. But when you start to think about things in terms of evolutionary terms, you have to get away from the idea of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ in the short term and start thinking about what leads to better reproductive success in the next generation of offspring,” he says. “So on one hand, certainly, risky behavior has a negative impact for survival. People who engage in risks may die at younger ages. But in terms of evolution, there is a big reward for taking those risks. You can get a better partner—a more fit, higher quality partner—and have greater reproductive success. And there is certainly some suggestion in the anthropological literature that people who engage in risks have greater reproductive success. So there seems to be an evolutionary benefit.”

In fact, new research suggests that males have evolved unique biological mechanisms that actually change the chemicals in the brain in such a way to promote greater risk-taking when a man finds himself around an attractive female, to help him garner her attention as well as intimidate any potential rivals nearby. I can’t help think that Darwin would have been tickled to see such results.

So switch out the pretty feathers for a cool indie band t-shirt—and maybe a couple wicked snowboarding tricks for those heroic deeds of old—and you can see that Darwin’s whisker comparison still hits the mark. Today’s males, like their evolutionary ancestors, parade their charms with so much pomp and rivalry for one of the greatest purposes of all—greater reproductive success for future generations.

Kayt Sukel is a passionate traveler and science writer, she has no problem tackling interesting (and often taboo) subjects spanning love, sex, neuroscience, travel and politics. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, the New Scientist, USA Today, Pacific Standard, the Washington Post, ISLANDS, Parenting, the Bark, American Baby, National Geographic Traveler, and the AARP Bulletin. Her new book The Art of Risk: The New Science of Courage, Caution, & Chance is available now!

Kayt Sukel is a passionate traveler and science writer, she has no problem tackling interesting (and often taboo) subjects spanning love, sex, neuroscience, travel and politics. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, the New Scientist, USA Today, Pacific Standard, the Washington Post, ISLANDS, Parenting, the Bark, American Baby, National Geographic Traveler, and the AARP Bulletin. Her new book The Art of Risk: The New Science of Courage, Caution, & Chance is available now!

We are excited to have two (2) copies of The Art of Risk in this month’s Book Giveaways. Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 3oth to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaway

Kayt Sukel, “The Art of Risk”

June 13, 2016

Beans at bedtime? How to dream well

By Helen King (Monthly contributor)

V0047952 A sleeping woman is disturbed in her dreams

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Have you ever tried writing down your dreams? I had a phase of doing this in my teens. The first thing I did on waking was to see how much I could recall, and I wrote it down immediately – dreams fade very quickly. Why was I doing it? I’m not really sure, but I must have got the idea from reading something. I think it was to do with identifying themes and trying to work out why they were so dominant; was my subconscious trying to tell me something? In the process, I learned the useful technique of how to wake myself up if the dream was going in a very bad direction; I can still do that.

Many people in the ancient world and beyond have thought dreams were powerful, but there is also a strong thread of scepticism. In the second book of Cicero’s On Divination (De divinatione), a debate with his brother Quintus, Cicero tells us that the followers of Pythagoras forbade beans before bedtime, for those who wanted to have more reliable dreams. He correctly observed that “there is hardly ever a night when we don’t dream” so, on the ‘monkeys typing Shakespeare‘ principle, it’s not surprising that sometimes dreams come true.

What do dreams mean?

Cicero also refers to professional dream interpreters. One of the most extraordinary survivals from the ancient world may well be a late second-century CE text, Artemidorus’ Differentiations of Dreams (Oneirocritica), the only example of a dream interpretation book to survive from antiquity. Unlike some modern examples of the genre (and I think I once owned one of these…) which list a symbol and then decode it, Artemidorus thought it was very important to know who was doing the dreaming because a similar dream image could have a very different meaning depending on whether the dreamer was slave or free, rich or poor, in power or not.

Dreaming of a cure

What about the power of dreams to reveal your illness? I once had a series of vivid, terrifying dreams of rivers of blood. I was sufficiently disturbed to go to my general practitioner, who listened carefully and concluded that this could indicate a recurrence of endometriosis. He was right. The Hippocratic treatise Regimen IV suggests that dream interpreters are better at some types of dream than others. They aren’t so good at particular types of dream in which the condition of the body is revealed. For example, the author of this treatise says, in dreams involving a struggle of some sort, the best response when you wake up is to take an emetic and increase your amount of exercise gradually.

However, some people in ancient Greece and Rome went further, believing that the dream could reveal a specific cure. In the sanctuaries of Asklepios across the Greek and Roman world, women and men came pursuing a healing process that included time to dream; the god could heal you during this dream or give you a remedy to apply when you woke up. The most famous patient in the ancient world, Aelius Aristides, spent an unusually long time in the sanctuary dreaming and seeking a cure; he came to see his many illnesses as evidence that Asklepios was particularly close to him.

Artemidorus agreed that the gods can send dreams which cure the dreamer or which tell the dreamer what to do to recover. The example he gives in book 5, where he collects actual dreams, is the man with a stomach problem who prays to the god Asklepios to give him a remedy, and then dreams that the god offers him his fingers to eat. The man then eats five dates and is cured; dates are called daktyloi, ‘fingers’. Here, then, the role of the dream interpreter is to find the pun in the dream’s contents.

Dreaming with Minerva

When I was reading Cicero’s challenge to his brother Quintus’ belief in the power of dreams, I was interested to find this section:

What would be the sense in the sick seeking relief from an interpreter of dreams rather than from a physician? Or do you think that Aesculapius and Serapis have the power to prescribe a cure for our bodily ills through the medium of a dream and that Neptune cannot aid pilots through the same means? Or think you that though Minerva will prescribe physic in a dream without the aid of a physician, yet that the Muses will not employ dreams to impart a knowledge of reading, writing, and of other arts? If knowledge of a remedy for disease were conveyed by means of dreams, knowledge of the arts just mentioned would also be given by dreams. But since knowledge of these arts is not so conveyed neither is the knowledge of medicine. The theory that the medical art was imparted by means of dreams having been disproved, the basis of a belief in dreams is utterly destroyed.

“Minerva will prescribe physic in a dream without the aid of a physician”… What’s this about? Minerva (sort of the Roman version of Athena, although the parallels between Roman and Greek deities can miss out some interesting differences) was one of many goddesses with a healing role. On just one inscription, from Italy, she is ‘Minerva Medica’, Dr Minerva. From the same site, one woman dedicates to her for the restoration of her hair, another after being freed of a serious illness “by the grace of her medicines”. Perhaps in these inscriptions we have an insight into the realities of people dreaming under the influence of a goddess.

Rather than avoiding beans before bedtime, Artemidorus suggests that what mattered most was to invoke the power of the god or goddess before you went to sleep. Others – like Cicero here – may be suggesting that, even if your initial hint that something’s wrong comes in a dream, your first port of call should be the physician.

To find out more:

Steven M. Oberhelman (ed.), Dreams, Healing, and Medicine in Greece: From Antiquity to the Present (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013).

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucgajpd/medicin...

June 10, 2016

Gleaning by Day and Freeganism by Night

By Thomas Parker (Regular Contributor)

In 2000, the French movie director Agnès Varda brought attention to the tradition of gleaning with her documentary The Gleaners and I. Gleaning (glanage), or collecting the edible leftovers from a farmer’s field after the harvest, has been permitted by law in France since 1554 and remains on the books today.

The Gleaners (1898)- Léon-Augustin l’Hermite

Gleaning takes place a day or two after the harvest and before the farmer lets the animals in the fields to graze or forage, placing the gleaner symbolically between civilized society and the animal world. The original law stipulated that only women, children, the old, sick, and destitute could participate, and that no tools (rakes, shovels, shears, etc.) be used. Tools separated “harvesting” from gleaning, implying the wielder’s agency and mastery of the land.

Instead, the gleaner humbly submitted to nature, the landholder, and society in general, passively receiving their generosity. As Varda put it, the gleaner is perpetually observed bending down toward the earth. A sort of symbolic submission.

Gleaning was authorized only in non-fenced-in fields from dawn until dusk, providing transparency that nothing illegal was taking place. In England, where the practice was also common, a bell rang in the opening and ending of the gleaner’s day. Along with being tightly framed in time and place, gleaning was defined in clear moral and philosophical terms. The Old Testament, often cited with regard to gleaning, observes “When you’re harvesting your field, if you forget a sheaf, don’t go back out into the field to get it. Let the foreigners, orphans, and widows take it. If you do this, the Eternal your God will bless everything you do” (Deuteronomy, 24:19). In France, gleaning was so much construed as a right bestowed by natural law that hiring a third party to gather what the harvest had overlooked, and thereby depriving the gleaner, was considered immoral if not illegal.

Les Glaneuses (1857)- Jean-François Millet

But as time went by, the gleaner’s role in society did not remain so clear-cut. In 1857, the artist Jean-François Millet unveiled a large painting that shocked the Parisian viewing public. It portrayed three women gleaners foregrounded in epic proportions normally reserved for heroic scenes. Notwithstanding their brazen placement on the canvas and their imposing physical size, the faces and the identities of the women remained obscured.

Moreover, despite their size, the women were depicted below the painting’s horizon in the bent posture described by Varda. The mix of the humble and the bold stirred emotions that were further exacerbated by the meager amounts gleaned by the women contrasted with the huge golden stores of harvested wheat overflowing in the background. A man on horseback supervised the harvest from above, completing the statement of societal inequity.

Tension beyond that of this provocative piece arose in other ways in the decades to follow. In the twentieth century, the mechanized world had a further effect on gleaning since the earliest machinery left inordinate amounts of produce in the fields. Farmers considered the gleaners of these copious leftovers as thieves, a stigma that remained even as machinery became more effective. Gleaning, once marked by its openness, was more and more viewed with a disapproving eye. Pushed increasingly out of the rural landscape, gleaning remained rampant in the urban cityscape, where it is now known as “freeganism” (or “récup” in French, from the word récupération).

In many cases, the diurnal licit practice of the country is a nocturnal illicit practice in the city. Instead of appearing as a normal sight in highly circumscribed parameters of time and place, gleaning has been pushed to the margins of alleyway supermarket rubbish bins. In some French communities, such as Nogent-sur-Marne, gleaning (or freeganism) has been outlawed with fines of 38 euros imposed on anyone breaking the law. The town government makes the argument that it is an unsanitary practice. But for many, gleaning remains rooted in the cultural consciousness as an undeniable right.

Freegans landing from above on a dumpster. Photo credit: Ben Nelms

Beyond what stories of freeganism and gleaning tell us about food waste, the transformation is interesting in symbolic terms. The gleaner no long appears as a gatherer, peacefully pecking at the ground, as in the Millet painting, but more as a predator. Instead of melting into the landscape, the freegan challenges societal practices. She skulks through alleys, and pops up from the shadows, shaming societal practices by reclaiming all that has been stigmatized and rejected.

June 6, 2016

Ancient Spartan Boy Killed by Windblown Frisbee

Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Murder by a gust of wind killed the beautiful youth Hyacinthus in ancient Greek myth. It was said that Zephyr, the West Wind, was once as churlish as his brother Boreas, the North Wind. His character was transformed into a gentle “zephyr” of Springtime by the beautiful nymph Anenome, whose flowery head nods in the soft, pleasant breezes in the Greek countryside.

But another myth describes Zephyr’s earlier, malevolent nature. The tale blames the West Wind for the death of Hyacinthus, a youth beloved by Apollo. In the story, Zephyr was consumed by jealousy when he observed Hyacinthus and Apollo taking turns tossing a discus one spring day. Zephyr impulsively blew a strong, sudden gust of wind. The gust caught up the discus and caused it to boomerang back at Hyacinthus. The edge of the metal Frisbee struck him on the forehead, killing him instantly.

How strong was that deadly gust? According to the modern Beaufort Scale (invented in 1805) for measuring wind force, winds are rated from 0 to 12. At Force 0, smoke rises vertically and gossamer (fine spider silk) floats in the calm air. This weather condition describes the summer day in the fourth century BC when Aristotle watched tiny spiderlings on fine webs wafting over a meadow.

At Force 4, “moderate breeze,” one’s hair is ruffled and skirts flap, and mosquitoes stop biting.

Between Force 6 and 7 (25-38 miles per hour), you would find walking into the high wind difficult. Umbrellas turn inside-out, and trees toss and sway. Bees, butterflies, and most birds seek shelter.

By Force 9, “strong gale,” dragonflies are grounded, small children are blown over, tiles are blown off roofs, and the only birds still airborne would be swifts.

Adults are toppled and trees are uprooted at Force 10. Hurricane warnings are issued when winds reach Force 12, over 70 miles an hour.

It seems reasonable to declare that Zephyr’s fatal gust of wind would probably rate a Force 8, “fresh gale,” with a wind speed of 39-46 miles per hour.

It was said that the hyacinth flower was stained by the dead youth’s blood.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014).

June 3, 2016

An Asbestos Purse at the British Museum

by Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

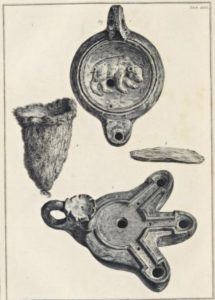

The purse and natural asbestos on either side, with lamp pieces upper and lower.

John and Andrew van Rymsdyk’s guide to the British Museum, Museum Britannicum (1778), is an intriguing and fun little book. It introduces the reader to a small group of objects on display in the late eighteenth century at the British Museum, which ranged from gems and amulets to kidney stones and sepulchral lamps. The book contained drawings of and historical reflections on each chosen object, with the authors making reference to books in the Museum’s library, as well as their own experience. I could linger happily on many aspects of the book, but allow me to introduce the ugliest (I think) item in the collection: an asbestos purse.

The engraving in the book (pictured here) does it few favours, but the modern photo at the Natural History Museum shows that it hasn’t aged well. Why would anyone want such a purse?

The book is provides a short history of asbestos (pp. 55-56), suggesting that asbestos properly belonged in the British Museum, being a native stone found throughout the British Isles (as well as many other parts of the world). Its appearance is unusual, even pretty: ‘whitish silver colour, consisting of small threads or longitudinal fibres’. It wouldn’t dissolve in water… and it would resist fire, only becoming whiter when it burned!

The van Rymsdyks were particularly interested in the potential applications of the stone. While short fibres were only good for making paper or torches, but longer fibres—which could be found in Aberdeenshire, no less—could be used to make cloth. This had two benefits. As van Rymsdyk reported, cleanliness was one use:

I have seen a Gentleman, a kind of Philosopher, at Amsterdam, who had a tasty Night-cap of it, which when foul he would throw into the fire, and became better clean than if it had been washed with soap and water, as we do linen.

The Ancients, according to the author, prized the cloth even more than pearls. It was used as shrouds for royalty, wicks in perpetual lamps, treating skin problems (!), and more. But the second greatest use might be to save lives—and could even be manufactured in Britain, using British stones. Van Rymsdyk implored: ‘For how many Ladies, Valetudinarians and Children have been burnt by their Cloaths catching Fire, for want of them being made from the Asbestos?’

The feasibility of asbestos cloth-making had been called into question earlier in the century. In his Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences (1728), Ephraim Chambers commented that although many

have pretended to the Secret of spinning the Asbestos… this should seem hardly practicable, without the Mixture of some other very pliant Matter, as Wool, Line, or Hemp along with it; the Filaments of the Amianthus it self being too brittle to make any tolerably fine Works (147).

Indeed. The purse is not ‘tolerably fine’, although it was more clothing-like than the other examples of asbestos cloth in the British Museum, which included ropes, nets and paper. That, presumably, was the reason for the van Rymsdyks including it in their guide to the Museum: a chance to highlight the possibilities for British industry and health.

Fibrous tremolite asbestos on muscovite. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

As to who would want the purse in the first place: Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753). The purse came from Sloane, whose collection was the founding core of the British Museum. Sloane had purchased it from Franklin in 1725, no doubt fascinated by the human industry in creating a fire-proof purse out of a natural curiosity–a stone with fibres.

I had brought over [to London] a few Curiosities among which the principal was a Purse made of the Asbestos, which purifies by Fire. Sir Hans Sloane heard of it, came to see me, and invited me to his House in Bloomsbury Square, where he show’d me all his Curiosities, and persuaded me to let him add that to the Number, for which he paid me handsomely.

Although Franklin did not elaborate on how the fibres were made tough enough to weave, Pehr Kalm (Swedish-Finnish naturalist, 1716-1779) later noted that Franklin had told him the method; when the fibres were left outside in the cold, wet air of winter, they would ‘grow together and become tougher and more suitable for spinning’.

But just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should. Given that asbestos can cause itchy skin, it would have made for some terribly uncomfortable clothes—for children and ill people, no less! Knowing what we do about asbestos now, it’s just as well it wasn’t used even more widely than it already was.

Plus: the cloth is ugly.

June 2, 2016

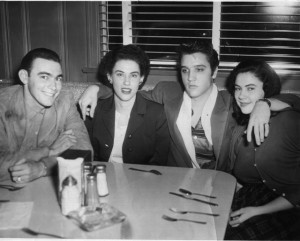

Nashville Chrome

By Rick Bass (Guest Contributor)

Everyone’s heard of Elvis Presley, yet almost no one has heard of the Browns. This amazes me, for the Browns’ story – hardscrabble Depression era beginnings, startling and almost eerie natural talent, incandescent rise to fame, trials and tribulations followed by a sudden return to utter obscurity – far exceeds even the drama of Elvis, who grew up with the Browns, was essentially an adopted member of their family, touring with them in the early 1950s, during the formative years when he first gave up his aspirations of becoming a famous gospel singer and chose instead the path of rock and roll.

Everyone’s heard of Elvis Presley, yet almost no one has heard of the Browns. This amazes me, for the Browns’ story – hardscrabble Depression era beginnings, startling and almost eerie natural talent, incandescent rise to fame, trials and tribulations followed by a sudden return to utter obscurity – far exceeds even the drama of Elvis, who grew up with the Browns, was essentially an adopted member of their family, touring with them in the early 1950s, during the formative years when he first gave up his aspirations of becoming a famous gospel singer and chose instead the path of rock and roll.

The Browns – siblings Maxine, Jim Ed, and Bonnie – possessed a soothing, tempered harmony that better than any other characterized the reassuring, silken sound of the 1950s, even as the turbulence of the 1960s awaited, just across the threshold of their fame.

The Browns were the first group to have a number one hit on both the country and pop charts, establishing a business model of the crossover genre that still exists today, and drives much of the music industry’s commerce, allowing entertainers and artists such as Keith Urban, Brad Paisley, Robert Plant, Alison Krauss, and countless others, to move freely and with the acceptance of popularity wherever they wish, musically. From the very beginning, greatness was attracted to them. Legendary producer and studio musician Chet Atkins called them his favorite group to record. The Beatles toured with them in England and sought to learn to harmonize like the Browns, calling the Browns their favorite American group. And then they were gone.

The oldest Brown, Maxine, maintains and daily examines a web page.

Rick Bass’s fiction has received O. Henry Awards, numerous Pushcart Prizes, awards from the Texas Institute of Letters, fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, among others. Most recently, his memoir Why I Came West was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Rick Bass’s fiction has received O. Henry Awards, numerous Pushcart Prizes, awards from the Texas Institute of Letters, fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, among others. Most recently, his memoir Why I Came West was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Image Credit: Maxine Brown

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in October 2010.

June 1, 2016

The Naked Truth About French Postcards

by Raisa Rexer, Guest Contributor

As anyone who has strolled the Seine in Paris has undoubtedly discovered for themselves, part of the charm of the Parisian booksellers, or bouquinistes, that line its banks (already described by Rachel Mesch on this very blog) is the fact that they are not necessarily purveyors of good taste. I am not simply referring to the overpriced reprints of Doors concert posters from the 1970s or the tacky plastic souvenirs hawked to tourists alongside gems of 19th century publishing; they also sell wares of a decidedly naughtier—but equally historically important—kind. Many bouquinistes have been known to display an ample collections of “French Postcards,” titillating vintage photo postcards of scantily clad women that made “French” a synonym for “sexy” in the early twentieth century and that remain popular with tourists today. Reprints that date to the 1920s, these postcards have a frisson of worldly sexiness tempered with the charm of a bygone and (supposedly) more innocent era, when a Parisian woman in a slip and stockings was as exciting as things got.

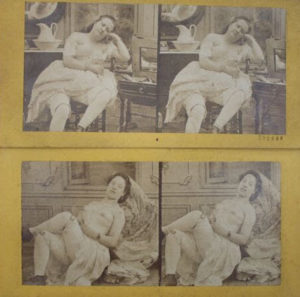

An “académie” from the 1850s by Félix Jacques Antoine Moulin

But as the very same bouquinistes could have shown us if we were perusing their wares some 150 years ago, those halcyon days of sepia-toned innocence never existed. The “French Postcards” of the 1920s are just one part of a long and complicated history of nude photographic imagery in France. Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre took the first photograph using the process that would later come to be known by his name in 1837, and two years later the French government patented the daguerréotype process for public use. From that point on, photography’s popularity exploded in France and around the world, a popularity that quickly included the nude. In the late 1840s, some of the great photographers of the day, like Félix Moulin, Gustave Le Gray and Charles Nègre, were already experimenting with the nude. Many of these images were not only works of art, they were even approved for sale by the government. Under the strict censorship system of the Second Empire (1851-1870), any written or visual materials sold in France had to be pre-approved by the government. In the 1850s and 1860s, thousands of académies, the term used for artistic nude studies meant to stand on their own or to be used by painters and sculptors in their work, were eventually approved for sale. Courbet, Delacroix, and Gérôme worked from specially commissioned photographic académies; images that were not private commissions were sold at the École des Beaux Arts and at print and photography shops around the city.

Not all of the images approved by the government, however, had such lofty artistic aspirations. Profiting from vague censorship standards and popular demand, photographers also submitted many images featuring scantily clad women. These small-scale (and usually stereoscopic) images included portraits of actresses and society figures baring shoulders or stocking-clad legs, as well as more racy “genre scenes” of women lolling around in their petticoats while exposing

Lamie et Augé, 1860s

breasts or thighs.

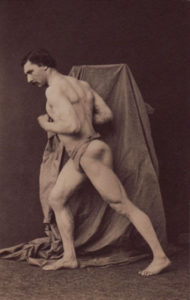

Léotard by Pesme, 1860

In 1860, the great scandals of the year were a pair of portraits: one of the can-can dancer Rigolboche, in which (in the words of the Goncourt brothers) she “showed her legs in all their positions” and a half-naked picture of the male acrobat Léotard in his underwear that was making women across Paris swoon. These racier images often received conditional authorization and usually could not be publicly displayed, but they could nevertheless be sold legally from behind the counter of a photography or print shop, just like académies.

The more brazen photographers went even further, forgoing authorization at all and photographing women and couples in various states of undress and sexual activity. The first obscenity prosecution for pornography took place in 1851; by the 1850s and 1860s, these explicitly pornographic of photos could be found all over Paris. Street peddlers of everything from umbrellas to toiletries hawked them across the city as a more lucrative clandestine side business. They were sold in ever-increasing quantities in wine shops and on cafe terraces, in outdoor markets and in the back rooms of photography and print shops, and (of course) by the bouqinistes along the Seine.

A legal image from Louis Camille D’Olivier, 1860s

In October of 1860, a police raid on the home of the photographer Auguste Belloc, who was possibly the most explicit and prolific pornographer of the Second Empire, turned up over 4,000 prints and negatives, including many that would make the proverbial sailor blush. With the fall of the Empire in 1870, the relaxation of censorship laws, further technological advances in the 1870s and 1880s, and the growth of an international industry that crossed European boundaries and exploited conflicting laws to avoid prosecution, the number of photographs increased dramatically. When he was arrested in Paris in 1892, a photographer operating under the pseudonym “Léar” had managed to distribute some 800,000 obscene photographs in under three years. It is entirely possible that some two to four million nude photographs were in circulation by the end of the nineteenth century, many of them graphically pornographic and not actually produced in France at all.

The charmingly retro “French postcard,” it turns out, was tame even for its time. In fact, it was tame even for half a century before its time. It is a relic of a past that didn’t actually exist, which explains its appeal and makes it, despite its veneer of eroticism, just like any old kitschy souvenir that packages an experience of a place through stereotype rather than reality. On the other hand, the bouquinistes are just doing the same thing that has always been done. If they did start selling historically accurate nude photographs from the 1860s, they might very quickly find themselves fined or locked up. Better that they stick to their postcards.

Raisa Rexer received her PhD in French from Yale University, where her research focused on the early history of the French photographic nude and its relationship to literary representation in the nineteenth century. She is a freelance art critic and instructor of French at Yeshiva University and City College, CUNY.

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column  on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.

on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.