Holly Tucker's Blog, page 15

May 26, 2016

Hints of Cherry and Witch’s Urine? (1400 AD)

By Tony Perrottet (Guest Contributor)

Today’s oenophiles have to consider the possibility that their valuable wine bottles may be corked, oxidized, “maderized” (ruined due to over-heating), re-fermented (gone fizzy in the bottle) or sullied by a contaminant.

Today’s oenophiles have to consider the possibility that their valuable wine bottles may be corked, oxidized, “maderized” (ruined due to over-heating), re-fermented (gone fizzy in the bottle) or sullied by a contaminant.

Things were much easier in 16th century Italy: You could just blame the witches. It was commonly believed that after their satanic midnight Sabbath parties witches had the nasty habit of invading a village’s wine cellars and sullying the vats with their urine or excrement. This, needless to say, did nothing for a wine’s bouquet. Thousands of European women were being burned at the stake for their evil powers, but somehow the problem could not be controlled.

The situation was better if you happened to live in northern Italy’s alpine province of Friuli on the border with Austria (still a fine wine-producing region), because there dwelt a team of occult heroes: the benandanti, or Good Walkers, a revered group of men who practiced white magic for the protection of local vintners. These specialists were identified at birth – they emerged from the womb with their faces wrapped in the caul or amniotic membrane – and as they grew up, they were instilled with a sense of sacred duty. By adulthood, a Good Walker would regularly slip into a deep, trance-like sleep, when his spirits could leave his body and sally forth to do battle with the witches. Not only would these spirits protect the wine in the cellars, they saved the annual crops from devastation and stopped witches from sucking the blood from infants or stealing souls from the innocent. Often,

these supernatural wine regulators returned from their moonlit journeys victorious; at other times they woke up exhausted and defeated.

Around 1575, the Inquisition grew suspicious of these strange men, but after many extended interviews, investigators decided to class their gifts as “benign magic” rather than satanic, and no executions were ever carried out. Perhaps, like many a gout-ridden cleric of the period, they too were connoisseurs of the grape.

Further Reading: Ginzburg, Carlo, The Night Battles: Witchcraft & Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth & Seventeenth Centuries , (London, 1966).

, (London, 1966).

Image: Courtesy of MSNBC

Tony Perrottet is author of Napoleon’s Privates: 2,500 Years of History Unzipped , The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games

, The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games , and Pagan Holiday: On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists

, and Pagan Holiday: On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists , among others. He can be found at TonyPerrottet.com.

, among others. He can be found at TonyPerrottet.com.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in September 2009.

May 23, 2016

Juggernaut

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Juggernaut cart in Bangalore, India, ca. 1870. Image courtesy of Leiden University Library

In the twelfth century, an Indian ruler built an important temple at Puri, in modern Orissa, where the Hindu god Krishna was worshiped in the form of Jagannatha (Lord of the World). The most important of the annual festivals associated with the Jagannatha temple was the Chariot Festival. The god’s image was placed in a highly decorated wagon and taken on procession from the temple to the country house of the god. The wagon was so heavy that it takes hundreds of worshipers to move it. The procession was accompanied by thousands of pilgrims, who crowd around the wagon. Between the crush of the crowd and the weight of the wagon, accidents were common. Occasionally an ecstatic pilgrim threw himself under the wagon’s wheels.

Quiet devotions by individual worshipers don’t make much of a story. Huge crowds and an inexorable wagon that crushes worshipers under its wheels? The stuff that travelers’ tales are made of. As early as the 14th century, European travelers in India were fascinated by the story of the Chariot Festival, and the worshipers who “cast themselves under the chariot, so that its wheels may go over them, saying that they desire to die for their god.” (Friar Odoric, c 1321. Just to give an example.)

In the nineteenth century, more than one responsible British official checked the Orissa province records and reported that the instances of death by chariot wheel were greatly exaggerated. It didn’t do any good. The story of the chariot of Jagannatha had become a metaphorical juggernaut, capable of crushing mere facts beneath its wheels.

May 19, 2016

What Color is your Habit?

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (Former Regular Contributor)

In the early fifteenth century male ecclesiastical visitors to the convent of Santa Clara in Barcelona cited the nuns for wearing an irregular and inappropriate habit. Rather than donning the traditional garb of Franciscan nuns, a gray or brown habit, the nuns wore a black habit more like that of the Benedictine Order. The visitors objected, but the nuns resisted and stuck to their sartorial guns. Stubborness prevailed on both sides  of the debate and the contest over their habits dragged on for about a century and was ultimately appealed to Rome. Why were both sides so persistent? How did a question of clothing reach all the way to the papcy? Considering that the nuns were rarely, if ever, seen by others, why did it matter what they wore?

of the debate and the contest over their habits dragged on for about a century and was ultimately appealed to Rome. Why were both sides so persistent? How did a question of clothing reach all the way to the papcy? Considering that the nuns were rarely, if ever, seen by others, why did it matter what they wore?

I have written previously here about the ways in which premodern clothing made statements about class and identity. It was not different for the nuns. Despite the fact that one modern historian has trivialized the decision of the Santa Clara nuns, claiming that the nuns simply wanted to exchange a drab habit for a more prestigious one*, it is clear that there was much at stake for these Franciscan women.

In fact, although Franciscan, the convent had a history of wearing the Benedictine habit. The nuns traced unbroken lineage to what they called the habit of San Damiano. This was a reference to the first religious community personally founded by Saint Clare in the early-thirteenth century. Because there was a ban on new religious orders when the community was formed in 1219, Cardinal Hugolino had placed the women under the Benedictine Rule. For the nuns of Santa Clara of Barcelona wearing the Benedictine habit let them claim an institutional identity built on a centuries-old connection between themselves and their sainted foundress. The nuns resisted the attempts to make them wear the Franciscan habit, and ultimately transferred the convent to the Benedictine Order. The local Franciscan hierarchy objected vigorously and appealed the decision to Rome. But the papacy upheld the nuns’ choice.

Another dispute over habits rooted in questions of identity erupted at the convent of Le Vergini in Venice. Here, in the early sixteenth century, the Augustinian nuns fought over a different choice of colors. A group of nuns was sent to reform the community and they wore grey habits. The original members wore white. After some discussion the two groups reached an agreement that they would all wear white. Trouble ensued, however, when the lay sisters (women who didn’t take solemn vows and frequently performed more menial tasks around the convent) adopted this color for their habits. Their decision violated a long-standing tradition of distinguishing between the habits worn by choir nuns and habits worn by lay sisters—a kind of hierarchy within the convent. The solemnly professed nuns wanted to be certain that the color of their habits signified their status as distinct.[1]

Habits, then, though hardly ever seen by outsiders, embodied important issues. Despite the monastic lifestyle’s insistence upon washing away attachments to material culture, habits mattered immensely to the women who wore them. Woven through their colors were questions of identity, tradition, and hierarchy.

* Interestingly, because of the dyes needed to prepare it, black was an expensive color to produce in the late Middle Ages, which may have made black habits a more prestigious item.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

[1] For more on this story, see Kate Lowe’s, Nuns’ Chronicles and Convent Culture in Renaissance and Counter-Reformation Italy (New York, 2003).

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in August 2012.

May 17, 2016

The Nazi Brain Removal Caper

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

After the end of World War II, a Nazi leader dies in Allied custody under strange circumstances. An American military psychiatrist longs to prove his pet theory by having the Nazi’s brain removed from the body and examined. With help from a friend, the psychiatrist succeeds in extracting the organ and smuggling it out of Europe. A pathologist studies the brain to determine the correctness of the psychiatrist’s theory and the result is. . .well, it’s complicated.

Nazi Robert Ley’s brain, as photographed by the U.S. Army Institute of Pathology.

This happened, not in a bad science fiction film of the 1960s, but in real life, in Nuremberg, Germany; Washington, D.C.; and beyond.

I first came across the story while researching my book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII. One of the first artifacts I encountered among the records of Douglas Kelley, M.D., a psychiatrist who had exclusive access to the top captured German leaders awaiting trial in Nuremberg for war crimes, was a set of glass slides. The slides showed different views of a dissected human brain. The label on the slides said the brain came from a man named Robert Ley.

I knew Ley as the emotionally unstable and hard-drinking head of the German Labor Front, a Nazi government agency that replaced trade unions and took charge of the affairs of German workers. Under Ley’s direction, the organization played a role in the gathering and mobilization of slave laborers, many of whom suffered and died in criminally brutal conditions.

Kelley met Ley during the summer of 1945, when the German was imprisoned and awaiting trial with 21 of the most culpable of his colleagues from the Nazi government and German military. The psychiatrist had assigned himself the task of determining whether a common mental disease or disorder afflicted the captured Germans and could explain their crimes against humanity. Ley, with his spells of shouting, crying, and proclaiming his allegiance to Adolf Hitler, was a subject of interest to Kelley.

Through the use of Rorschach inkblot testing and other psychological assessments, Kelley theorized that Ley — alone among the top German defendants — suffered from a behavioral disorder originating in the brain, the result of an airplane crash Ley had experienced World War I. Kelley’s tentative diagnosis of organic brain injury was bold, given the psychiatrist’s lack of access to any kind of brain imaging when examining Ley.

Ley became his Allied captors’ nightmare when he managed to strangle himself in his Nuremberg cell in October 1945. Kelley called Ley’s suicide a blessing, because it offered hope that the dead man’s brain could testify to the truth of Kelley’s brain-damage diagnosis. Kelley convinced a friend, U.S. Army pathologist Najeeb Klan, to secretly remove Ley’s brain in the Nuremberg morgue. Kelley then sent the brain, enclosed in a wooden crate marked “Spices,” on a transatlantic journey. It soon reached another of Kelley’s colleagues, neuropathologist Webb Haymaker, at the Army Institute of Pathology in Washington , D.C. In the process, it became the only brain of a Nazi leader given post-mortem scrutiny. Kelley asked Haymaker to examine the brain for signs of frontal-lobe damage.

Haymaker wrote back to Kelley that Ley’s brain evidenced “a long-standing degenerative process of the frontal lobes.” He couldn’t tell if a head injury caused the degeneration. Nevertheless Kelley felt exhilarated by the supposed prescience of his chancy diagnosis.

Joel E. Dimsdale, distinguished professor emeritus and research professor in the department of psychology at the University of California, San Diego, has unearthed more about the silent testimony of Ley’s brain. In his research, he quotes Nathan Melamud of the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute, who in 1947 took his own look at Ley’s brain tissue at Haymaker’s request. “I am not impressed with any definite pathology in this case,” Melamud wrote, “at least such as would lead one to suspect a clinical organic condition…. [I]f real, the changes are not too significant.”

Kelley’s reaction to this less affirming second opinion is unknown. He had other things to ponder. By 1947, Kelley was deeply into the writing of a book that laid out his proposition that the German leaders had been infected by no psychiatrically active “Nazi virus” that accounted for their behavior. That declaration — and its implication that the German leaders were psychiatrically normal — did not go down well with the American public.

Further reading

Dimsdale, Joel E. Anatomy of Malice: The Enigma of the Nazi War Criminals. Yale University Press, 2016.

Smelser, Ronald. Robert Ley: Hitler’s Labor Leader. Berg, 1988.

May 16, 2016

Captain Cook’s Cook

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

In the history of seafaring misadventures in the waters off Hawaii, there are two that are particularly well known. In 1779, on the shore of Kealakekua Bay, with his ship anchored within sight just a short distance away, Captain James Cook was killed in an altercation with Hawaiian natives. Forty-five years later, in Hanalei Bay off the island of Kauai, the most famous pleasure yacht of the age was wrecked on a reef. Known as ‘Cleopatra’s Barge’, the boat had been built in 1816 by George Crowninshield, the wealthy owner of a Massachussetts shipping business. It had sailed to the Hawaiian islands in 1820, and been sold to the Hawaiian King Kamehameha II.

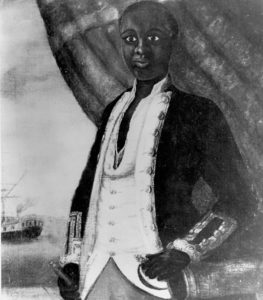

Amazingly, it seems that there was one man who served on ship with James Cook who also was a crew member on the ill-fated Cleopatra’s Barge. Even more surprising is this man’s origins – he was a black man named William Chapman, who in 1776 had signed on in England as a young member of James Cook’s crew. Forty years later, William Chapman was serving as the cook on Cleopatra’s Barge.

Amazingly, it seems that there was one man who served on ship with James Cook who also was a crew member on the ill-fated Cleopatra’s Barge. Even more surprising is this man’s origins – he was a black man named William Chapman, who in 1776 had signed on in England as a young member of James Cook’s crew. Forty years later, William Chapman was serving as the cook on Cleopatra’s Barge.

Born in England, Chapman was something of a curiosity to the American crew of Cleopatra’s Barge. In his journal of the voyage to the Mediterranean in 1817, George Crowninshield mused on the particular character traits of “our cook born in freedom”. Not only was Chapman an excellent organizer of all events and necessities on board, he impressed everyone with the range of his knowledge and experience. He told fascinating stories of living in Hawaii after Cook’s voyage there: “this man lived three years in Owyhee, where he took a wife, according to the customs of the country. He is an intelligent fellow … and has given many interesting particulars of the manners, customs, religion, history, state of learning, etc. of the people.”

Whether or not his official responsibilities on the Cook expedition included work in the kitchen, the observant Chapman would have learned some innovative culinary skills onboard James Cook’s ships. Cook was famous for bringing fresh produce aboard at his stops and encouraging his sometimes reluctant crew to eat new things that he believed would help to keep them healthy. In Hawaii, he had brewed beer from sugar cane and ordered that the rum supplies be saved as long as there was cane beer on hand.

Chapman also acquired considerable knowledge of navigational techniques during his years of seafaring. In 1817, Cleopatra’s Barge became the first American pleasure craft to traverse the Atlantic. Once in Europe, the ship made stops to allow visitors to come on board and examine the famous luxury yacht. One such visitor was Franz Xaver von Zach, a prominent German astronomer, who boarded the boat in the port of Genoa. Zach described the experience in a letter. He was initially especially interested in the skills of the ship’s navigator, particularly his ability to determine longitude by lunar observations. But what really astounded him was the ship’s cook, who, he was told, “could calculate longitude quite well, and his taste for it frequently led him to do it. … This cook had sailed as a cabin boy with Captain Cook on his last voyage round the world, as was acquainted with several facts relating to the assassination of that celebrated navigator.” Chapman was summoned from the kitchen and told to answer the questions posed to him by the visiting astronomer. Standing there “with a white apron around his waist, a fowl in one hand, and a carving knife in the other,” the cook proceeded to accurately describe the methods he had learned and the books he had studied. After further discussion the cook and the astronomer together poured over Chapman’s notes: “I saw all the calculations this negro had made on the passage, of latitude, longitude, apparent time, etc. He replied to all my questions with admirable precision, not merely in the phrases of a cook, but in correct nautical language.”

Chapman also acquired considerable knowledge of navigational techniques during his years of seafaring. In 1817, Cleopatra’s Barge became the first American pleasure craft to traverse the Atlantic. Once in Europe, the ship made stops to allow visitors to come on board and examine the famous luxury yacht. One such visitor was Franz Xaver von Zach, a prominent German astronomer, who boarded the boat in the port of Genoa. Zach described the experience in a letter. He was initially especially interested in the skills of the ship’s navigator, particularly his ability to determine longitude by lunar observations. But what really astounded him was the ship’s cook, who, he was told, “could calculate longitude quite well, and his taste for it frequently led him to do it. … This cook had sailed as a cabin boy with Captain Cook on his last voyage round the world, as was acquainted with several facts relating to the assassination of that celebrated navigator.” Chapman was summoned from the kitchen and told to answer the questions posed to him by the visiting astronomer. Standing there “with a white apron around his waist, a fowl in one hand, and a carving knife in the other,” the cook proceeded to accurately describe the methods he had learned and the books he had studied. After further discussion the cook and the astronomer together poured over Chapman’s notes: “I saw all the calculations this negro had made on the passage, of latitude, longitude, apparent time, etc. He replied to all my questions with admirable precision, not merely in the phrases of a cook, but in correct nautical language.”

We do not know what became of the remarkable William Chapman after the boat on which he served as cook was sold to King Kamehameha II. Chapman already had lived in Hawaii, and knew the route that Cook had taken from England. There is some evidence that he sailed with Cleopatra’s Barge on its voyage from America to the Pacific in 1820, because some Russian visitors who visited the ship in Hawaii noted an “African servant offering drinks” onboard.

Chapman certainly had managed to navigate his own path very well up until then. I like to think that he ended his days in comfort on a tropical island, serving as skipper on a pleasure boat of his own, and studying the night sky.

Illustrations: The Death of Captain Cook, by Herb Kawainui Kane; The Wreck of Cleopatra’s Barge, by Richard Rogers; Cleopatra’s Barge in Genoa Harbor, sketch by Benjamin Crowninshield, Jr.; Portrait of an African American Sailor, c. 1780, artist unknown.

For further reading: Paul F. Johnston, Shipwrecked in Paradise: Cleopatra’s Barge in Hawai’i (2015)

May 13, 2016

Literary Chefs

By Michael Garval (Regular Contributor)

Fig. 1: Auguste Blanchard II, Antonin Carême (1833)

Chefs as Writers

Early celebrity chefs were haunted by their collective past, by centuries of domestic service. Fleeing the ignominy of their profession, they coveted the prestige of literature. So in portraits they rarely wore chefs’ garb, and instead posed as writers.

Perhaps the first celebrity chef, Antonin Carême (1784-1833) was the subject of flattering portraits. Some surround him with writerly trappings–pen, books, desk–and foreground his writing hand. Others, like Blanchard’s engraving (fig. 1), feature unruly hair, swirling drapery, dark eyes, and a broad thinker’s forehead. Carême appears a Romantic genius, like Lord Byron, or a young Victor Hugo.

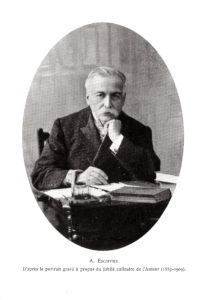

Portraits of the great Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935) likewise present him not as a chef, but as a distinguished man of letters. In a frontispiece portrait commemorating his culinary silver jubilee (fig. 2),

Fig. 2: Frontispiece portrait, Auguste Escoffier, Les fleurs en cire (1910)

light illuminates his head. The usual writerly paraphernalia–pen, paper, inkwell, books, desk–occupy the foreground, with the dark paneling of his study behind. Escoffier ponders his next sentence, left hand against his chin, supporting the repository of his intellect. His right hand is poised, not to skim stock, but rather to transcribe his lofty thoughts.

Literary Imposture

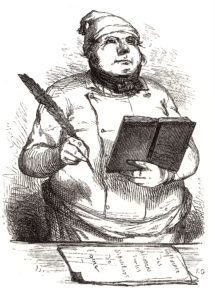

Such pretensions were satirized broadly. In one illustration (fig. 3), the would-be cook of letters wears an ill-fitting uniform accentuating his prominent belly. Light shines upon his powerful jowls, rather than forehead, with his toque pulled low for a more Neanderthal effect. These details emphasize ingestion and digestion rather than higher cerebral functions.

Fig. 3: Bertall, illustration for Eugène Briffault’s Paris à table (1846)

Yet this dimwit aspires to literary grandeur. His pudgy face gazes outward, aping pensive attitudes struck by chefs like Carême. He holds a book and oversized pen awkwardly, composing a learned treatise on the “Influence of foodstuffs upon the dispositions of the soul.” But the manuscript lies perpendicular to him, an impossible angle for putting pen to paper. Such an oaf writes badly, or just doesn’t know how.

The gap between this chef’s literary ambitions and real abilities might seem preposterous. But it actually recalls the case of Alexis Soyer (1810-1858), the top French chef in mid nineteenth-century England.

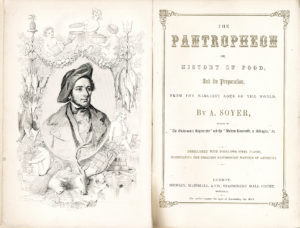

In his ambitious but ghostwritten Pantropheon, the barely literate Soyer trumpeted his ostensible literary prowess. An elaborate frontispiece (fig. 4) surrounds his portrait with a grandiose allegory of food, and food writing. Below, alongside running water, tilting books marked Homer, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Pliny, and Apicius spill over into the text ahead.

Fig. 4: Frontispiece, Alexis Soyer, The Pantropheon or, the History of Food, and Its Preparation, from the Earliest Ages of the World (1853)

Placing Soyer in this impressive lineage, the frontispiece vaunts his supposed expertise, authority, and stature as a writer. But such bogus claims also reveal the scope of his literary imposture.

Writers as Chefs

Nowadays culinary work, like cooking in general, enjoys unprecedented cachet. Freed from earlier stigmas, today’s high profile cooks embrace their professional identity. Whether in photographs, advertisements, food shows, documentaries, or websites, they sport chefs’ uniforms, flaunt knife skills, and showcase signature recipes.

Tables have turned. Where chefs once posed as writers, they now pose as chefs. In a revealing twist, writers also get cast as chefs. And this becomes apparent through one current trend in particular.

Literary foodbooks have abounded in recent years. These popular volumes highlight noted authors’ recipes and gastronomic musings, recreate dishes from their works, evoke meals from their period and milieu, and depict key elements in their gastronomic universe (kitchens, dining rooms, favorite restaurants, etc.). Some, like The Pat Conroy Cookbook, look at contemporary writers. But most, like Anne Borel’s Proust, la cuisine retrouvée, focus on canonical figures from the past two centuries. They hark back to a time when the realm of letters still offered chefs a shining if unattainable ideal.

Today however, foodbooks are turning literature into a vast smorgasbord, a delightful gastronomic romp. Authors, no longer the cultural beacons of yore, get rehabilitated as inspired cooks and enlightened eaters, whose culinary creations and diets somehow exemplify their special sensibility and personal magnetism.

Chefs once cloaked themselves in the flattering guise of literature. With the relative decline of literary culture, and concurrent rise of food culture, the landscape has shifted. Now writers bask in the newfound luster of the kitchen.

May 11, 2016

Museum Mysteries: Murder Bottles

By Michelle Marcella

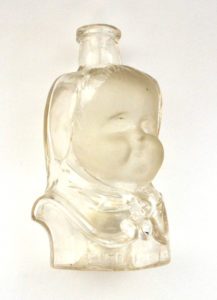

A 19th-century baby bottle.

Behind the scenes at the Russell Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital, there sits a box labeled “Collection of nursing bottles, breast pumps and nipple shields.” These baby nursing supplies are similar to those of a contemporary hospital nursery except that these artifacts date to the late 19th century, when bottle feeding was a brand-new concept. The little glass bottles were meant to ease the burden of child care that Victorian mothers faced. Often sporting such whimsical names as “Feed The Baby” and “Mummie’s Darling,” the bottles were patented and introduced in the late 1800s. Although many women continued to breastfeed, bottle feeding became a way to help those mothers who were unable to breastfeed, could not afford a wet nurse, or who wanted the freedom of not having to be accessible for feeding 24 hours a day – as well as wrestling multiple times throughout the day with a restrictive corset.

The bottles worked simply. After the banjo-shaped bottle was filled with liquid, often cow or breast milk, a long rubber tube was inserted through a stopper in the bottle’s thin neck. The section of the tube outside the bottle was fitted with a rubber nipple. The shape of the bottle and the length of the tube allowed a child to hold and eat from the bottle without help, giving mothers freedom to take care of other household duties.

An array of nursing supplies, including a glass breast pump.

With this modern convenience, however, came untold tragedy. Infant mortality rates during the late Victorian era were high, with fewer than two babies of every ten surviving until two years of age. While providing sustenance, these bottles also delivered poison to many of the babies. Bacteria of all kinds flourished in the difficult-to-clean hoses, and the design of the bottles, unlike those of the more open household bottles and jars, also provided breeding grounds for molds and diseases. Even the Victorian age Martha Stewart wasn’t helpful. Isabella Beeton was a household management guru and her 1861 book, Mrs. Beeton’s Household Management, provided counsel on everything that the busy lady of the house needed to know about child rearing, and how to keep her household in tip-top shape. When it came to baby bottles, this domestic guru advised that washing nipples every two to three weeks was sufficient. Unfortunately, the impure environment of the rubber nipple allowed for even more bacteria to grow with abandon, and added to the contaminated bacteria already collecting in the bottles.

A banjo-style nursing bottle closed with a ceramic stopper, and with remnants of original rubber hose inside.

By the time Buffalo, New York outlawed the bottles in 1897, they had acquired the moniker “murder bottles.” After widespread condemnation by medical communities in the U.S. and abroad, many other cities and states followed suit. Surprisingly, however, the bottles continued to be available and popular until the 1920s as the promise of independent feeding remained appealing.

Michelle Marcella is the operations and finance manager at the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital.

May 9, 2016

Bodies at breakfast, and a grand day out

by Helen King (monthly contributor)

I was recently talking to a breakfast group about ‘Bodies, ancient and modern’. No, I don’t know why they wanted to hear about bodies at breakfast, either – I prefer to focus on my muesli. In the section in which I talked about the history of gaining knowledge of the body, I showed a slide of one of Gunther von Hagens’ plastinated corpses, and I made the point that – although what you are seeing is a real body, treated after death to preserve it – they end up looking a lot more dry and hence ‘unreal’ than the wax images of the eighteenth century. Von Hagens is known in the media as ‘Dr Death‘ and his bodies do, indeed, look very dead, regardless of the lifelike and active poses in which they end up. Interesting questions about ‘reality’ and art are raised by this. When you consider a wax image, the colors and the shine of the wax give a far more ‘wet’ and thus ‘real’ impression than any real but subsequently plastinated body.

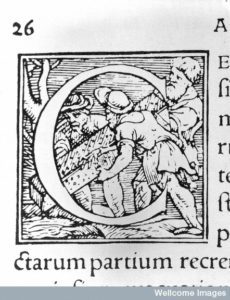

Many years ago, I taught a few sessions on an MA degree, ‘Death and Society’, set up by Tony Walter. It was an interesting course, taken by a number of funeral directors as professional development, as well as by others from all walks of life. I taught them how cadavers were treated in the early modern period in order to ‘make’ skeletons for teaching purposes. Illustrated here in one of Vesalius’s capital letters from Fabrica (1543), you can see one stage, in which the corpse was treated with quicklime and then that was washed off by placing the coffin, pierced with holes, in a river. You can see the corpse’s hand coming out from under the lid…

L0028523 A. Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica, 1543

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

At the end of one year’s course, in 2002, I was invited on the official course outing. This had two parts. First, we went to von Hagens’ Bodyworlds exhibition, then on display in East London. I admit, I was in two minds about this. It’s one thing looking at representations of bodies, even flayed or dissected ones – but quite another to gaze at a body and know it was once a living person who at some point donated his or her mortal remains to be treated and displayed. Here, I’m glossing over the claims that not all of the bodies one sees in the exhibition came by that route, claims which add their own spice to the experience, as they recall the history of body-snatching in the production of anatomical knowledge.

The people going round the exhibition were a mix of ages and backgrounds. Some brought along their children or partners, in some cases because one of them was in a medical job and wanted the other to see what it’s all about. Some came because of a particular personal experience; I watched one woman talk another through the display of damaged and replacement hip joints, sharing what had happened to her. Being with the MA group, which included archaeologists, gave me an extra dimension, as they pointed out to me that von Hagens’ focus was on muscles, and his treatment of bones was often less careful and left sharp edges visible.

I was doing absolutely fine until I came face to face with a representation of a man carrying his own skin. No, wait, let’s get this right: with a real human body posed with his skin. This is an image used by Vesalius, and seeing real bodies in poses deliberately recalling iconic images of the history of medicine is enough to make anyone confused about where the boundaries lie! But in this case, a further disorienting factor was the soles of the feet. Somehow, those were very personal, a vivid reminder of just what I was really looking at.

And then we had lunch. I wasn’t as hungry as usual. For the second part of the outing, we went to a London funeral parlor. Including the mortuary and the embalming room.

![By Nick Webb from London, United Kingdom (Skin) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1462866746i/19052536.jpg)

By Nick Webb from London, United Kingdom (Skin) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

And do you know what? It was nowhere near as disturbing as the soles of that man’s feet.

May 4, 2016

From the Past, with Love

by Rachel Mesch

by Rachel Mesch

The book arrived from eBay or Priceminister.fr, I can’t remember which. Both sites are cherished resources for bric-a-brac-o-maniacs like myself: places where you can find old magazines, post cards, and out of print books. As they (should) say, one man’s trash is a nineteenth-century scholar’s treasure. If you know what you are looking for, you can save yourself trips to inconvenient libraries and struggles with microfilm readers–no fun for reading entire novels. If you are lucky, for the price of a few Euros, you can avoid the rules of the rare book room and read in the comfort of your own easy chair.

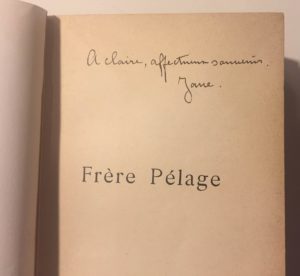

And so it was for the obscure nineteenth-century French novel I was hunting down this time around, Jane Dieulafoy’s Frère Pélage, a work of historical fiction published in Paris in 1894, never to be reprinted. The compelling narrative that I ultimately found within the yellow volume would inspire a lengthy academic article to be published in the coming months, and nourish the seeds of a book project now in progress. Driven by these interests and by my literary training, I dug into that book over two summers, returning to its enigmatic yet promising paragraphs, rereading and taking notes. I might have noted the library binding on the fat volume’s spine and the evidence of its sad ejection from the University of Keele that permitted its sale to me: “withdrawn from stock” stamped over the empty white slats of the check-out slip. One man’s trash…

around, Jane Dieulafoy’s Frère Pélage, a work of historical fiction published in Paris in 1894, never to be reprinted. The compelling narrative that I ultimately found within the yellow volume would inspire a lengthy academic article to be published in the coming months, and nourish the seeds of a book project now in progress. Driven by these interests and by my literary training, I dug into that book over two summers, returning to its enigmatic yet promising paragraphs, rereading and taking notes. I might have noted the library binding on the fat volume’s spine and the evidence of its sad ejection from the University of Keele that permitted its sale to me: “withdrawn from stock” stamped over the empty white slats of the check-out slip. One man’s trash…

“To Claire, with fond remembrances, Jane”

Somehow, I had missed the author’s own inscription.

It seems that the Jane Dieulafoy novel that I had purchased for seven Euros through a massive online auction house had once been owned by the nineteenth-century author herself. And so the object that I had treated as “just” a book—a means to an end—a way to read a novel came to bring me closer to my own subject in ways I had not anticipated. It turns out that Jane had offered my copy to “Claire,” with her “fond remembrances” (Claire Meslier her sister? Claire Dieulafoy her sister-in-law? Claire from the convent that had partly inspired this fictional exploration of Catholic tradition?) before it made its way to the University of Keele and then an online French vendor and eventually me. And I know it is indeed that Jane, Jane the author, because her signature is familiar to me after countless hours of poring over her letters in Parisian archives—libraries that require special permissions and protective gloves.

As with any historian, the literary scholar thrives on contact with the past, relishes any evidence that her human subjects lived and breathed, treasures the way in which those proofs collapse time and space. There is a reason that autographed copies by celebrated authors command huge fees on the same auction sites where I found Jane’s novel. I love her tender dedication all the more knowing that she and her novel are no longer famous and that I am one of the few who know not just of her writing but of her breathtaking accomplishments (she and her husband traveled to Baghdad and Persia in the 1880s, bringing back treasures still on display in the Louvre). I do hope that when I publish my research—much of it biographical—others will come to appreciate her extraordinary life (no spoilers in this post, but stay tuned!). But for now I keep Jane’s message to the unknown Claire as a personal reminder of the life connected to the stories that she told, and of my duty to take special care in my own writing of that fierce yet delicate legacy, filled as it was with fond remembrances.

**

Rachel Mesch’s article on Jane Dieulafoy’s fictions will appear in an upcoming issue of PMLA, the publication of the Modern Language Association.

May 2, 2016

How Would Ancient Amazons Celebrate Mother’s Day?

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

According to ancient Greek myths, the fierce horsewomen-archers known as “Amazons” were the antithesis of ideal womanhood, the opposites of docile stay-at-home moms of classical Greece. Some Greeks even claimed that the name amazon meant “without a breast” in Greek and insisted that the warrior women mutilated themselves in order to shoot a bow more easily.

Greek poets such as Pindar described Amazons beating drums and performing bellicose war dances for the stern virgin goddess of the hunt, Artemis. Artemis was definitely not a mother figure.

The Greeks came up with a lot of contradictory notions about Amazons. But no one imagined a sentimental picture of Amazons as maternal, nurturing mothers like those celebrated in modern Mother’s Day cards. For the Greeks, Amazons were either man-hating killer-virgins who refused marriage and rejected motherhood and gloried in making war–or else they were lusty, domineering women who used random men for sex, stealing their sperm in order to perpetuate their women-only society.

Lurid stories claimed that Amazons only raised their baby girls and abandoned or mistreated infant boys–breaking their legs or even killing them. None of this is the stuff of Hallmark cards.

Yet archaeological discoveries tell a different story. The historical models for mythic Amazons were warlike women of nomadic Eurasian tribes and their graves contain battle-scarred female skeletons buried with arrows and spears. But many of these women were mothers too: next to their quivers of arrows archaeologists sometimes find the remains of children who died prematurely.

Archaeological evidence also reveals that real-life Amazons worshipped Cybele, the great mother goddess of Anatolia (her rites required that men castrate themselves). Amazon family trees were matrilineal–the famous Amazon queens of myth could trace the names of their illustrious warrior mothers, grand-mothers, and great-grandmothers.

So, although there would not be flowers or breakfast in bed for Amazon moms, the Amazons of antiquity would definitely understand the concept of daughters honoring their mothers on Mother’s Day. Amazon sons, maybe not so much–and don’t even ask about Father’s Day!

About the author: A research scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014), winner of the Sarasvati Prize for Women in Mythology and The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.