Holly Tucker's Blog, page 12

September 12, 2016

Poisons and love potions

By Helen King (monthly contributor)

V0035920 Circe. Engraving by W. Sharp, 1780, after J. Boydell

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

http://wellcomeimages.org

Everybody knows that the ancient Greek word pharmakon means both healing drug and poison. So how could you tell the (rather important!) difference? In Latin, the equivalent term venenum was similarly used in both senses, and Roman law codes tried to tie down that ambiguity by making it clear whether a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ venenum was meant. The Digest of Roman law issued in the sixth century AD explained that all ‘drugs’ (in Latin, medicamenta) can be considered venena, because a medicamentum is simply something that, by being used, changes the nature of the thing to which it is applied.

An important way of tying down the ambiguity of pharmaka and venena is dosage. It was well known in ancient medicine that one and the same substance had different powers depending on how much of it is administered: in a small dose, it could be a love potion; in a larger dose, it would cause madness, sleep or intoxication; and in a very large dose it could kill.

Who knows what?

So, who knew this? Only physicians, or everyone else? An Athenian legal speech dating to the period 420-411 BC is interesting here. What’s the story? The accused is the stepmother of the man doing the talking. She’s on trial for poisoning her husband – his father. The deed was done when he was pouring a libation to a god, which meant drinking some of the wine himself. Also present at the crime scene was a young woman who was the slave and sexual partner of Philoneos, a friend of the speaker’s father. Philoneos had decided to rent out this young woman as a prostitute in a brothel: she was less than happy about the idea. The stepmother befriended this slave and told her that she too was being wronged by a man (that is, the speaker’s father), and that both of them needed to take action right now to restore the love of their partners. The stepmother announced that she had the means, but needed the slave to help her, and she handed over a pharmakon to the slave:

Goddess pouring libation: kylix, attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter (Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011)) [CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b... Wikimedia Commons

Philoneos’ mistress, who poured the wine for the libation … poured in the pharmakon with it. Thinking it a happy inspiration, she gave Philoneos the larger draught; she imagined perhaps that if she gave him more, Philoneos would love her the more: for only when the mischief was done did she see that my stepmother had tricked her (Antiphon 1, Prosecution of the stepmother for poisoning, 19).That’s so poignant, isn’t it? ‘If I give him more, he’ll love me more…’ Oh dear. This young woman is being presented as woefully ignorant of the importance of dosage! There’s a similar story in ps-Aristotle’s Magna Moralia (16, 1188b30-38), where a woman is acquitted on a charge of murder with a philtron because ‘she gave it to him for affection, but missed her mark’. Oops.

A philtron is a term for a drug/poison given specifically to inspire love. In the law court speech, made by the prosecution, the choice of the word pharmakon rather than philtron disrupts the story, making it less about a love potion that went wrong (focus on the silly slave), and more about a deliberate poisoning (focus on the wicked stepmother).

The fate of Philoneos

What happened to Philoneos? Receiving such a large dose, he died instantly; but the speaker’s father was also taken ill and died twenty days later. So, if the slave had not given her master so much to drink, it seems he would still have died from the drug. It looks like the stepmother’s dosage recommendation was cunningly set at a level where there would be a delayed effect, making it less obvious what the cause was, and thus less likely that the culprits would be identified. But the younger woman’s enthusiasm ruins the older woman’s plan. Here, as often in the classical world, women are associated with poison; not only does it require no physical force, but also it fits well with women’s roles in food and drink preparation.

This story shows that sudden deaths were most suspicious, but also that any death, whether rapid or gradual, could with hindsight be attributed to poison. In both Greek and Roman law, showing intent to kill was critical because, at least for citizens, accidental poisoning merited a less severe penalty than deliberate poisoning. Following the death of the two Athenian citizens, the stepmother is eventually brought to trial.

And the slave girl…?

But what of the young woman who put the pharmakon in the wine? While we hear a report of what was going through her mind – ‘Thinking it a happy inspiration’ – and an echo of her voice – ‘she imagined perhaps’ – she is long gone. Being a slave, she had been tortured and then executed.

To find out more:

Christopher A. Faraone, Ancient Greek Love Magic (Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1999)

September 10, 2016

Serving up Amuse-bouches: “big ideas in small bites”

By Michael Garval and Thomas Parker (Regular Contributors); photographs by Nigel Harkness

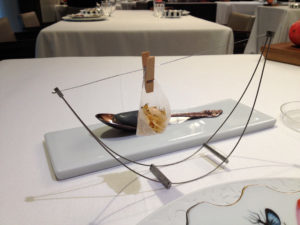

Amuse-bouches, Restaurant ES, Paris, France. Chef: Takayuki Honjo.

Welcome to our monthly food column, Amuse-bouches.

So what’s an amuse-bouche?

It’s a small dish, just a mouthful or two, served gratis at the very beginning of the meal, generally in a restaurant of some gastronomic pretension. While tiny, the amuse-bouche is designed to be tasty, eye pleasing, often playful, even whimsical, and at times provocative.

Formed from the French, it means “something to amuse your mouth.” The expression “amuse-gueule” appeared first, however, in 1946 (gueule is a familiar, somewhat vulgar word for mouth, like “trap” in the U.S. or “gob” in the U.K.). Amuse-bouche later emerged as a more polite alternative, and became the preferred term in restaurants, as well as in the English-speaking world.

At their best, amuse-bouches share something with the aphorism, the bonsai, the cameo, or other miniature forms that also pack lots of wonder into a little space.

Shrimp in a bag and Stone of Manchego. Ramon Freixa Restaurant, Madrid, Spain. Chef: Ramon Freixa.

Melon soup with basil. Abantal, Seville, Spain. Chef: Julio Fernández Quintero.

Unlike tapas, dim sum, and other small plates however, you don’t order amuse-bouches. Typically, at a given meal, all customers in a restaurant receive the same one, with the choice of dish not the diner’s but rather the chef’’s prerogative. As such, the amuse-bouche can be a kind of culinary trial balloon, what Melissa Clark calls “a testing ground, a safe place to try out a risky concept, tweak it to perfection and gauge reactions.”

Sea anemone in tempura. Restaurant Lasarte, Barcelona. Chef: Paolo Casagrande.

Salmon and Apple in a dome of smoke. Restaurant Ramon Freixa, Madrid, Spain. Chef: Ramon Freixa.

A prelude to the meal ahead, a pocket-sized showpiece, a site of delight and experimentation, the amuse-bouche offers insights into the chef’s culinary philosophy. As Jean-Georges Vongerichten has said (of Rick Tramonto’s Amuse-Bouche: Little Bites of Delight before the Meal Begins), “The amuse-bouche is the best way for a great chef to express his or her big ideas in small bites.”

Amuse-bouches, De Karmeliet, Bruges, Belgium. Chef: Geert Van Hecke.

It is our hope that, like their namesake, our brief Amuse-bouches blog posts will entertain, surprise, and challenge you. We look forward to trying out new ideas that expand our own vision of cuisine, gastronomy, culinary culture, and food history, and whet your appetite for further exploration and reflection. Along the way, we also welcome your thoughts, comments, and suggestions.

Happy reading, and bon appétit!

September 7, 2016

Unfinished History

by Rachel Mesch

A current exhibit at the Met Breuer museum in New York City features a pile of candies wrapped in brightly colored cellophane. Viewers are invited to take one, so that the work of art– by Felix Gonzalez-Torres–constantly shifts over time. This piece (“Untitled”) is part of the “Unfinished” exhibit—a meditation on artistic practices that probes in one hundred and ninety-three riveting and unexpected ways the question of artistic completion: when a work of art is finished, and what it means when it is not.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled,” 1991

Where does material culture fit into this set of questions? The bric-a-brac-o-maniacs among us are drawn, perhaps, to the material aspect of historical study precisely because of its unfinished nature: the possibility of a continued relationship with the past through direct contact with the objects that it left behind. We collect in order to keep the past from slipping away permanently, to keep it from being over. We deny that the past is finished by continuing to interact with it.

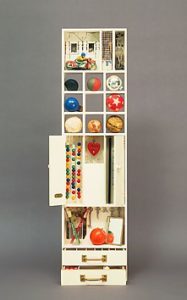

When it comes to the contemporary artworks in the Met’s exhibit, there is a tension within the show itself between the artistic desire to create a work of art built out of a relationship with the viewer and the art historian’s wish to preserve that desire in time. While Gonzalez-Torres’s candies are replenished once a day, a work by George Brecht featuring a cabinet with objects intended to be handled is displayed behind a glass cabinet meant to protect the work from those invited hands. In order to preserve Brecht’s work for posterity, the curators deny its current viewers the full experience of it.

George Brecht, Repository, 1961

I have been chided in the past by museum types for the way that I keep my own collection: the of early twentieth-century French women’s magazines that have been instrumental to my research, and which are now loosely stored in plastic bins. Each time I handle them the edges fray a bit more. Turn-of-the-century bindings slacken. There is an occasional tear. But I did not track these publications down from Parisian book sellers (and internet auction sites) in order to store them behind glass or bury them away in sealed plastic envelopes. The point is to handle them, not just the better to analyze them for my research, but-yes!- to allow the oil from my own fingers to sometimes mark them, if only just a tiny bit. Participating in the magazines’ inevitable entropy—another major artistic trope of the modern works in the Unfinished exhibit—is perhaps a way of working against the ephemeral, fleeting nature of the past. From a professional collecting perspective, my casual contact with the objects that I collect diminishes their value. From the perspective of a bric-a-brac-o-maniac, it is this very contact that keeps the magazine alive, and along with it, the enduring thrill of the unfinished.

**

For further reading, see the wonderful catalog from the exhibit, edited by Kelly Baum and Andrea Bayer, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible. Yale University Press, 2016.

September 5, 2016

Ancient Egyptians Collected Fossils

By Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Ancient Egyptian worshippers of Set, god of darkness and chaos, collected fossils of extinct beasts by the thousands. From 1300 and 1200 BC, nearly three tons of heavy, black fossils, polished by river sands, were brought to Set shrines on the Nile. Many of the bones were wrapped in linen and placed in rock‑cut tombs.

The immense troves of fossils heaped at Qau el-Kebir and Matmar were discovered in 1922-24 by archaeologists Guy Brunton and Sir Flinders Petrie, stunning evidence that Egyptians revered large stone bones as sacred relics of Set. The god was often associated with the hippopotamus, and many of the fossils belonged to hippos, but remains of extinct crocodiles, boars, horses, giant antelope, and buffalo were also found.

In 1926, geologist K. S. Sandford explored 500 miles around Qau but failed to locate the source of “this strange collection of animals,” which appear to be of the Pliocene‑Pleistocene era. Sandford commented, “We await the verdict of the paleontologist with the greatest interest.” In 1927, Brunton wrote that the tons of fossils would be “the subject of a special memoir”; in 1930 he again promised a volume devoted to the fossils.

But that was the last word about the extraordinary black bones of Set. The fossils were forgotten by the scientific community.

In 1998, I contacted paleontologist Andrew Currant, Curator of Quaternary Mammals, Natural History Museum, London, to inquire whether there were any records of the fossils discovered by Brunton and Petrie. Currant learned that a large “undocumented collection” of fossils from Qau were stored in a warehouse in Wandsworth. They were still in the original crates that Brunton and Petrie had shipped from Egypt. As I pointed out in The First Fossil Hunters (Princeton, 2000), the fossils gathered by ancient Egyptians more than 3,000 years ago–languishing in unopened crates in South London since 1920s–surely deserved scientific study by paleontologists and Egyptologists.

My book also described some Qau fossils wrapped in linen located in 1999 by archaeologist David Reese–who also tried in vain to convince the National Museum to open their crates of fossils. Reese learned that a collection of ancient Egyptian textiles from the Petrie Museum had been de-acquisitioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum and then acquired by the Bolton Museum (Manchester). In response to our queries, Angela Thomas, senior keeper at the Bolton, realized that some very ancient linen items of peculiar bulk had been inadvertently included with the textiles from the V&A. Labels scrawled on the backs of envelopes in Petrie’s handwriting confirmed that these bundles were some of the long‑lost linen‑wrapped fossil bones discovered at Qau in 1923.

Inspired by this intriguing report, Egyptologist Tom Hardwick and geologist David Craven at the Bolton opened an investigation to determine the identity of the bones in 2007. They introduced a “Bone Bundle Mystery” contest, with a prize for guessing what sort of fossil was inside one of the bundles. Unwrapping revealed the scaphoid (foot bone) of a giant, extinct antelope/wildebeest. (Curiously, the Bolton Museum has removed evidence of the contest and identification of the fossils from their website, despite renewed interest in the fossils in 2016.)

Seven years later, in 2014, another bundle at the Bolton was examined by X-ray CT scanning ( http://www.ironfromthesky.org/?p=276&...). In 2016, the Egypt Exploration Society awarded a grant ( http://www.ironfromthesky.org/?p=393 ) to Pip Brewer (Natural History Museum, London) and Diane Johnson (Open University) to finally unlock the dusty old crates that Currant, Reese, and I had located 16 years ago.

At long last, it appears that modern scientific analysis will determine the origins, species, and dates of the mysterious black bones of Set gathered by ancient Egyptians.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times; Fossil Legends of the First Americans; and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World.

August 16, 2016

1948: An American Psychiatrist Recommends Mental Evaluations of Political Office Seekers

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

As I wrote in my book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Douglas M. Kelley, M.D., had learned plenty about destructive heads of state by the late 1940s. A former U.S. Army psychiatrist, he had conducted psychiatric evaluations of the top German political and military leaders held for trial at Nuremberg on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity after World War II.

U.S. Senator Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, 1939

When he returned to the States in 1946, he spoke out against such American despots as U.S. Senator Theodore Bilbo and Congressman John E. Rankin of Mississippi and Governor Eugene Talmadge of Georgia, who tapped into veins of white supremacy and racial prejudice to manipulate constituents and attain political power.

By 1948, Kelley was convinced that the U.S. needed formal medical procedures to screen malign people from reaching political office. In an interview that year with a newspaper reporter, he argued for mandatory psychiatric evaluations of office seekers. He gave two reasons why the examinations would protect society. “There are at times grandiose characters in important governmental positions who have abnormal drives and their actions make life unbearable for other people and for society in general,” Kelley said. “If they get too much power, mental tests would uncover incipient Hitlers.”

The second reason: “Politicians are human and just as subject to mental diseases as anyone else.” Kelley added that the psychiatrists who examine political aspirants should also undergo evaluation, “as psychiatrists have the same problems as the politicians.”

Kelley knew what he was talking about. After years of emotional distress and self-imposed overwork, he committed suicide in 1958.

Further reading:

Bilbo, Theodore G. Take Your Choice: Segregation or Mongrelization. Dream House Publishing Company, 1946.

Post, Gerald (editor). The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

August 15, 2016

Pleasure and Death: An Englishman Travels to France after Waterloo

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Soon after the end of the Napoleonic wars, curious English tourists started pouring into France, eager to see the sights after years of restricted travel to the Continent. Guidebooks were in demand. Writers and painters caught up in the burgeoning Romantic movement sought out picturesque scenes, ruins, and quaint regional costumes and behaviors. Illustrated travel accounts were particularly prized.

One of the more unusual of these was one written by Richard Brinsley Peake, an artist and engraver who later would become known as a playwright. Like most young English travelers in 1816, Richard was seeking not only adventure but also relief from the violence and death that had touched everyone during the era of Napoleon. Like other English travelers he was also fascinated to see what France looked like after surviving the tumultuous and bloody period that had begun with the Revolution. And he wanted to understand better what the French survivors were like.

The illustrations in his book give an idea of what interested him most on his trip. The title says it is a book about “characteristic costumes” of France, but the substance is about much more than that. The opening scene seems to capture the ambivalence of the English visitor. He describes the nausea provoked by the voyage by boat across the channel and the amusement that he and his fellow seasick passengers inspired in the French who watched them land. He paints scenes from the street and public spaces, with almost every illustration including a reminder of the wars – a “mutilated” soldier, an old army officer in a coffee shop, begging children and widowed women holding babies. Almost every street scene includes men in uniform, no longer the soldiers of Napoleon’s army, but keepers of order from various branches of the civil guard.

The illustrations in his book give an idea of what interested him most on his trip. The title says it is a book about “characteristic costumes” of France, but the substance is about much more than that. The opening scene seems to capture the ambivalence of the English visitor. He describes the nausea provoked by the voyage by boat across the channel and the amusement that he and his fellow seasick passengers inspired in the French who watched them land. He paints scenes from the street and public spaces, with almost every illustration including a reminder of the wars – a “mutilated” soldier, an old army officer in a coffee shop, begging children and widowed women holding babies. Almost every street scene includes men in uniform, no longer the soldiers of Napoleon’s army, but keepers of order from various branches of the civil guard.

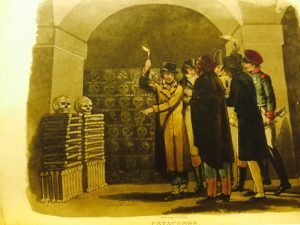

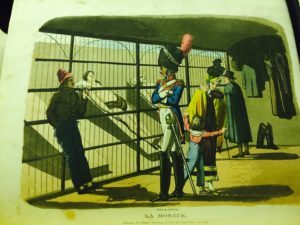

Many of the tourist destinations that Peake singles out have to do with either illicit pleasures (gambling dens, “pleasure-gardens”, dance halls) or death (The Catacombs). On the latter, he comments: “Melancholy suggests itself, on arrival at the place which was appropriated to the remains of the revolutionary victims of 1792.” He moves from his ‘Catacombs’ chapter to one titled ‘The Morgue’. In 1816, the Paris morgue was a public place, where unidentified bodies were put on display. In the description of his illustration, he imagines that the officer contemplating a female cadaver was himself the person responsible for her death.

Many of the tourist destinations that Peake singles out have to do with either illicit pleasures (gambling dens, “pleasure-gardens”, dance halls) or death (The Catacombs). On the latter, he comments: “Melancholy suggests itself, on arrival at the place which was appropriated to the remains of the revolutionary victims of 1792.” He moves from his ‘Catacombs’ chapter to one titled ‘The Morgue’. In 1816, the Paris morgue was a public place, where unidentified bodies were put on display. In the description of his illustration, he imagines that the officer contemplating a female cadaver was himself the person responsible for her death.

His illustration of “a trip to Versailles” is not of the architectural wonder itself, but of a carriage accident encountered on the way. People and possessions are strewn pell-mell on the road. In his description of this scene, Peake notes the horses, who he says were left  behind in France by the Cossacks and then put to work by carriage drivers who recovered them. He imagines the beasts’ harsh treatment as punishment for their work during the wars: “The French driver vents his spleen upon his former enemy, accompanying each lash with the epithets of ‘Ah! Vilain Cossaque’ …”

behind in France by the Cossacks and then put to work by carriage drivers who recovered them. He imagines the beasts’ harsh treatment as punishment for their work during the wars: “The French driver vents his spleen upon his former enemy, accompanying each lash with the epithets of ‘Ah! Vilain Cossaque’ …”

After his return to England Peake turned more seriously to writing. His best known play is an adaptation of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, a work written in 1816 by a young woman herself heavily influenced by the scars left by Napoleon’s wars. In Peake’s staged version, Frankenstein is completely dehumanized. He is mute and more grotesque than in Mary Shelly’s description, like one of the cadavers the English traveler had viewed on his trip to Paris, returned to a monstrous life.

For further reading: French Characteristic Costumes, by Richard Brinsley Peake. London, 1816. (Several editions are available on Google Books.)

August 12, 2016

The Most Famous Restaurant in US History

By Paul Freedman (Guest Contributor)

Few elegant restaurants have had their names recorded in the titles of best-selling books and only one that I know of was mentioned prominently in a Bugs Bunny cartoon. Antoine’s in New Orleans has both distinctions. Founded in 1840, nearly wrecked by financial difficulties and Hurricane Katrina, Antoine’s is still going strong as the oldest US restaurant owned by a single family.

Antoine’s Restaurant- New Orleans

Dinner at Antoine’s was a wildly popular mystery novel by the once-celebrated author Frances Parkinson Keyes that appeared in 1948. The first scene depicts the crowds waiting outside the restaurant, which took reservations only for its socially prominent regulars. The opening scene is a dinner party held in the glowing, red “1840 Room” starting a complicated story of passion and betrayal. So familiar was the restaurant to the American public that the concise title needed no elaboration.

The 1951 cartoon French Rarebit merely refers to Antoine’s, but again its fame requires no explanation. Bugs Bunny falls off a carrot truck and it turns out he is in Paris. Before he can take his bearings, two rival chefs grab him and a dispute ensues over who gets the right to cook the rabbit. The rest of the story involves a complicated escape that begins with a promise on the part of the rabbit that he knows an infallible recipe for “Louisiana Back Bay Bunny Bordelaise” as made at Antoine’s. The chefs are impressed and one of them asks, with something approaching awe, “Antoine’s, of New Orleans?” Bugs Bunny retorts, in his inimitable fashion, “I don’t mean Antoine’s of Flatbush”.

Interior courtyard at Antoine’s

If it has lost that universal level of fame, Antoine’s remain a wonder, both for its marvelous food and its timelessness. It has over a dozen variously decorated dining rooms, ranging in size from the Large Annex and the Japanese Room (the latter seating 200) to the tiny Tabasco Room with a capacity of six and the only slightly larger Escargot Room, originally the preserve of a private dining society. The menu is still in French, although there is an English translation provided (but only since the 1990s). The restaurant’s most famous specialty is Oysters Rockefeller, oysters cooked in their shells with a green sauce whose ingredients are known only to the owner and maybe one or two others.

From the beginning until sometime in the 1960s Boeuf Robespierre was a featured entrée, invented by the original Antoine Alciatore when he was a teenage chef in Marseilles. For the Prince Talleyrand, the eminent diplomat and political intriguer, Antoine prepared a special beef tenderloin saignant (i.e. rare enough to be still bloody) served with a sauce of beef stock, sweetbreads and chicken livers. Summoned from the kitchen to receive the great man’s compliments, the youthful chef was asked what he called the dish. He actually hadn’t thought to name it but, on impulse, he said “Boeuf Robespierre,” remembering his father’s description of the grisly execution of the French revolutionary leader.

Antoine’s menu cover

There are in addition at least two flambé dishes, Cherries Jubilee and Café Brulôt Diabolique (coffee mixed with brandy and spices), set alight at the table. Before the Second World War the restaurant owner, Jules Alciatore, said the kitchen could prepare over 1,000 different dishes and they had 560 recipes just for eggs. The list of marvels is endless.

Café brulôt diabolique

Thick, rich French sauces, waiters who seem to have been there since time began and a wonderfully formal but warm-hearted atmosphere, the restaurant seems to be a relic from a distant era even alongside the other grand establishments of the French Quarter such as Galatoire’s or Arnaud’s. When Anthony Bourdain visited in 2008 for an episode of No Reservations, he dined on Oysters Rockefeller, soft-shell crabs with brown butter, Tournedos Marchand de Vin and Baked Alaska. Bourdain assumed these were all prepared just for his visit as some sort of homage or ironic gesture to the restaurant’s past and was incredulous at being shown they were all on the normal menu and ordered all the time.

Soft shell crab at Antoine’s

For most of its history Antoine’s has identified its food as “French,” but it really amounts to a combination of French, Louisiana Creole and its own inventions. Perhaps to reaffirm its own pedigree, it either lacks or de-emphasizes certain popular creole dishes an outsider visiting New Orleans might expect: no jambalaya, only in recent years is gumbo given any prominence and alligator soup is new. It’s hard to think of another restaurant in this country serving European or American food that doesn’t list any pasta dishes.

Some changes are being made in order to draw in new patrons and to take advantage of a revival of the New Orleans restaurant scene and of the beleaguered city as a whole. One of the dining rooms was converted into the Hermes Bar with an informal, convivial atmosphere and a more grazing, small-plates set of dining options. The website is updated and there are special offers and promotions, something unthinkable in the past. The essential spirit of the restaurant, however, is intact and its physical and culinary restoration has made it more attractive than at any time in the recent past.

***

Paul Freedman is the Chester D Tripp Professor of History at Yale University. He specializes in medieval social history, the history of Spain, the study of medieval peasantry, and medieval cuisine.

His newest book, Ten Restaurants That Changed America (Norton, 2016) will be available in September 2016 and may be pre-ordered here.

August 9, 2016

Museum Mysteries: The Intern’s Step

By Sarah Alger

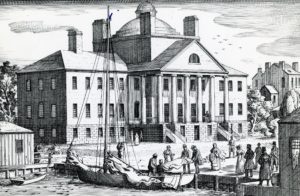

The original building of Massachusetts General Hospital, opened 1821.

Massachusetts General Hospital’s first building, designed by renowned architect Charles Bulfinch and opened in 1821, is an elegant granite edifice. Leading from the lawn up to its Ionian-columned second floor are two sets of stone steps. The top step of each has been known for decades as the Intern’s Step.

Like an April Fool’s joke that keeps giving all year, this top step is, on one set, half an inch higher than the rest, and on the other, a full one and a half inches higher. As Peter G. Barrett, MD, explains in Voices of the Massachusetts General Hospital 1950-2000: Wit, Wisdom and Untold Tales: “In the 1960s, anxious interns with clean, pressed, white uniforms hurried up the stairs each week on their way to teaching conferences. Early in the academic year, some of them would misjudge the top step and trip, scattering charts, papers and stethoscopes everywhere. All occurred within the view and the sound of the house staff and faculty who were gathered inside the nearby conference room.”

The Intern’s Step, with a red line of caution.

Did Bulfinch design this step on purpose for future humiliation and hilarity? Unlikely, says Jeffrey Mifflin, the MGH’s archivist. “My speculation is that there was some miscalculation at the foundation level during construction and that the extra-high final steps had to be put in place to compensate,” he told me. “Another possibility (again, speculative) is that the main part of the Bulfinch Building is resting on a foundation that sits on a spot that was excavated down to bedrock, while the staircase is on less solid footing, perhaps causing it to sink an inch and a half, requiring compensatory replacement steps to be added.” We’ll never know for sure.

The top few inches of these offending steps are now painted red. Whether anyone pays the red any mind, I don’t know, but I haven’t seen anyone trip on the step in my past two and a half years here, either (me included, thank goodness).

August 8, 2016

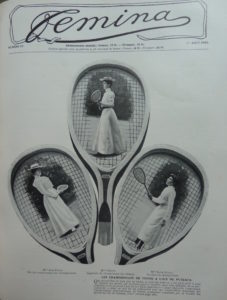

Sexuality and the body: using ancient sources to support modern ideas

by Helen King (monthly contributor)

Hyakinthos – Wikimedia commons

This post is adapted from an article on my personal blog,

Pausanias and Agathon: a ‘same sex relationship’?

In another aspect of my life, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how the ancient Greek past is used to in current debates about sexuality and the body. During recent discussions in my church, the Church of England, around equal marriage, one of the pressure groups issued a statement giving its answers to the sorts of questions which could come up in debate. One involves using two ancient Greeks – Pausanias and Agathon – as evidence that same-sex male relationships were familiar at the time when the New Testament was written.

Without getting into any of the details of the very heated church debates here, I just want to use this example to illustrate how carefully we need to read historical sources, from any period. As an ancient historian, I’m struck by the way some people tend to use the ancient Greeks without any sense of historical context or genre. It’s as if all sources are valid in precisely the same way. To make it worse, people can just ignore a few centuries – Pausanias and Agathon lived in the fifth century BCE, while the New Testament was written in the first century CE. While the pace of change in the past wasn’t what it is now, that’s still a long gap!

Why are we using the past?

The reason why Christians today want to bring Pausanias and Agathon into their arguments – whether for or against equal marriage – is simple. As the statement says, “Some have suggested that faithful same sex relationships were not known in (pre) biblical times and therefore the bible is silent on this matter. This is not true: such relationships are acknowledged by Plato and others, and it is likely that Alexander the Great was in a same sex relationship with Hephaestion, as was Pausanius with poet Agathon.”

So the argument being made here is that those who say the Bible doesn’t mention ‘faithful same sex relationships’ because they didn’t exist are wrong: such relationships did exist, so if the Bible had wanted to mention them, it could have done. Pausanias (not Pausanius) and Agathon are important because they are taken to show that it was possible for two men to be in a long-term faithful relationship.

Comparing categories

I’ve discussed elsewhere the range of different forms of behaviour that were around in the classical Greek world and which modern readers have too readily assimilated to ‘homosexuality’: an inappropriate amount of interest in personal grooming (seen, by the ancient Greeks, as indicating far too much interest in appearing attractive to women); temporary relationships in which one man (the erastês) was older and dominant with his partner (the erômenos) being younger and passive; male friendship with a strong spiritual bond but no physical expression; and men who preferred to dress and act in a way seen as ‘feminine’. Ancient categories weren’t the same as ours, so the category of ‘faithful same sex relationship’ simply can’t be applied.

Investigating the evidence

And how do we know about Pausanias and Agathon? The main source is indeed Plato, who in the Symposium imagines a conversation about love. Both Pausanias and Agathon are present, as is the playwright Aristophanes. No women are in the room, because the only woman who was there – a flute-girl – has been asked to leave. The men talk about whether love between a man and a woman is different from love between men, and conclude that the latter is better because men are, simply by being men, better. When it’s his turn to speak, Pausanias contrasts the bad sort of love, only interested in the body, with the good sort, attracted to the soul. One can feel the first sort for boys or for women, but the second sort is only felt for men. A boy should wait for the right sort of man, one who is interested in his soul rather than his body, and it is right for such a man to be given sexual access to the boy’s body.

The other main source for Agathon, a prize-winning playwright, is Aristophanes who, in his comedy Women at the Thesmophoria, has a very different Agathon: camp, and cross-dressing. Giulia Sissa identified these two Agathons – in Plato and Aristophanes – as two versions of the same man, and compares the ‘platonic glorification’ of one Agathon to the ‘comedic denigration’ of the other. So where is the real Agathon? We simply can’t say. It’s not just that in the two genres – Platonic philosophy and Athenian comedy – the same man comes out very differently, but that there’s an intertextual game going on between the two pieces of literature.

Other references to Pausanias and Agathon aren’t really additional sources, as they simply riff on Plato or copy each other. Aelian (2.21) and Xenophon (Symposium 8.32) refer to them as erastês and erômenos. The suggestion that the relationship was unusual because it went on longer than normal, beyond the point when the younger partner grows body hair, is clear. Aelian (13.4) and Plutarch (Moralia 177a) have an anecdote about the tragic poet Euripides getting drunk and kissing Agathon even though the latter was ‘about 40 years old’ (Aelian) or ‘already bearded’ (Plutarch). When challenged on this, Euripides replied ‘it’s not just spring that is excellent in attractive men – so is autumn’.

I’m not denying that Pausanias and Agathon were used in the ancient world as an example of a relationship which went on for much longer than the erastês and erômenos type normally did. But I do challenge the suggestion that we can map this on to modern relationships. To do that is to ignore genre and intertextuality in order to compare two sexual worlds that are entirely different, for both women and men: 5th century Athens and the 21st century Western world.

August 3, 2016

Olympic Preview, circa 1900

By Rachel Mesch

With the 2016 Summer Olympics ready to get underway, we can expect to be dazzled by gorgeous images of the world’s best athletes: gleaming, taut muscles in action, strength and determination fixed in seemingly endless, and endlessly seductive, photographic frames.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to note how far back this relationship between sports and photography goes—pretty much back to the birth of photojournalism itself. Pierre Lafitte’s La Vie Au Grand Air (roughly translated as “The Great Outdoors”) was the first photographic magazine published in France, in 1898 (that’s a whopping thirty-eight years before Sports Illustrated was born). The very concept of this magazine linked sports to what the camera could capture: it was billed as “an illustrated revue for all sports,” and sought a new market share in the exploding mass press by promising that over half of its material would be composed of images. For the late nineteenth-century reader, the thrill of this new media was very much the thrill of the visual, which offered a more intimate form of access and connection to sports than ever before. With technology improving technology with every issue, readers were provided an eye-catching perspective on athletic events, which they no longer had to attend in order to feel as if they were there. By the time of the summer olympics rolled around in 19

It’s worth pausing for a moment to note how far back this relationship between sports and photography goes—pretty much back to the birth of photojournalism itself. Pierre Lafitte’s La Vie Au Grand Air (roughly translated as “The Great Outdoors”) was the first photographic magazine published in France, in 1898 (that’s a whopping thirty-eight years before Sports Illustrated was born). The very concept of this magazine linked sports to what the camera could capture: it was billed as “an illustrated revue for all sports,” and sought a new market share in the exploding mass press by promising that over half of its material would be composed of images. For the late nineteenth-century reader, the thrill of this new media was very much the thrill of the visual, which offered a more intimate form of access and connection to sports than ever before. With technology improving technology with every issue, readers were provided an eye-catching perspective on athletic events, which they no longer had to attend in order to feel as if they were there. By the time of the summer olympics rolled around in 19 08, the magazine was able to offer stunning action shots, like the one here of American high jumper Porter, impossibly twisted, in mid-air.

08, the magazine was able to offer stunning action shots, like the one here of American high jumper Porter, impossibly twisted, in mid-air.

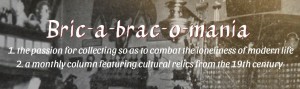

Just a few years after launching La Vie Au Grand Air, Lafitte came up with another journalistic innovation: to create a photographic magazine for women, directing all of his cutting edge technology and modernizing journalistic tools towards a female readership. Lafitte’s insight into market shares had, once again, everything to do with the visual: his publication, named Femina, quickly surpassed other women’s magazines precisely because it was so much more visually intriguing than, say, the reigning fashion rag, La Mode illustrée. While historians of photography recognize the importance of La Vie Au Grand Air, they have almost entirely overlooked Femina and its photographic innovations. The magazine worked tirelessly to stage a new image of the m odern woman who could balance work and family, and it harnessed the as yet untapped power of the photograph to make that case as compelling as possible.

odern woman who could balance work and family, and it harnessed the as yet untapped power of the photograph to make that case as compelling as possible.

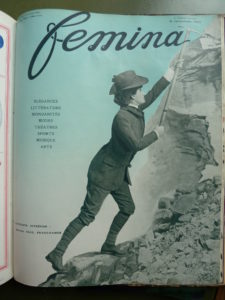

As an off-shoot of this imagery, Femina also promoted the female athlete as a celebration of modern femininity. Without baring too much of their own musculature, their female athletes seem delighted by their freedom of movement. You can see a slide show of them, as well as some in Femina‘s rival La Vie Heureuse, through this link. They are depicted as gracefu l and lovely, but most of all happy, joyously embracing the thrills of their sport—without breaking a sweat. These early female athletes are forward-moving creatures, decidedly modern with no trace of menace to the social structures they were quietly gliding over and past.

l and lovely, but most of all happy, joyously embracing the thrills of their sport—without breaking a sweat. These early female athletes are forward-moving creatures, decidedly modern with no trace of menace to the social structures they were quietly gliding over and past.

La Vie Au Grand Air delighted in early “photo-shopping” techniques: mixed media cutting and pasting that combined photographs with traditional journalistic artistic tools, pen and ink and watercolor graphic designs. You would think the surrealists were imitating them, fifteen plus years later. Femina often mirrored this fanciful take, all part of an early pleasure in the visual culture of sports, and a subtle acknowledgment of the ways in which our athletes have long defied the laws of physics.

La Vie Au Grand Air delighted in early “photo-shopping” techniques: mixed media cutting and pasting that combined photographs with traditional journalistic artistic tools, pen and ink and watercolor graphic designs. You would think the surrealists were imitating them, fifteen plus years later. Femina often mirrored this fanciful take, all part of an early pleasure in the visual culture of sports, and a subtle acknowledgment of the ways in which our athletes have long defied the laws of physics.

***

You can see more issues of La Vie Au Grand Air on the digital website of the French national library, gallica.fr. For more on Belle Epoque women’s magazines, see my book, Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman.

![Goddess pouring libation: kylix, attributed to the Villa Giulia Painter (Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011)) [CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)]via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1473854447i/20522540.jpg)