Holly Tucker's Blog, page 11

October 6, 2016

Culture of the Abdomen: A Family History

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

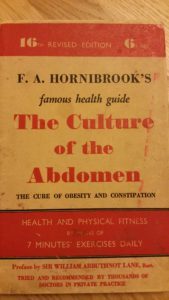

My grandfather, Elmer Smith, died in 1948. One of his personal effects recently found its way onto my dad’s bookshelf—it being an old book that no-one had much use for: F.A. Hornibrook’s The Culture of the Abdomen. We’re not even 100% sure that the book did belong to Elmer; there are no personal marks, just a feeling, or distant memory, on the part of my aunt (who had found it while doing a clear-out) that the book was probably her father’s.

I’m inclined to agree.

The first edition of Hornibrook’s popular health guide appeared in 1924, but this was the sixteenth edition, published in 1946. And that, I think, is the clue. Elmer, you see, died of bowel cancer.

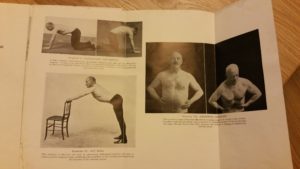

Hornibrook’s book was subtitled ‘the cure of obesity and constipation’ and focused on fixing the middle-aged spread in men. It’s great fun to read, with gems such as this:

His digestion if a mockery, gurgling and groaning in hopeless disability, his breath reminiscent of a Limburger cheese, and his general outlook upon life a pessimistic wail (7).

The exercises have much to offer the modern reader, as they are essentially about building core strength, including such staples as cat-arches, pelvis tilts, and belly dancing. Yes, you read that correctly, or, as Hornibrook put it: ‘abdominal muscle training, based upon the body-dance exercises of native races’ (19).

And the creator of the modern Squatty Potty was clearly influenced by Horniman’s advice on using a hygienic stool when at toilet. Throughout the book, Hornibrook compares unfavourably the bodily knowledge and practices of the West with ‘native’ cultures from around the world.

The Culture of the Abdomen is not about cancer, but the possibility of cancer runs as a dark theme through the book: the constipation that comes with civilisation and its bad habits was to blame for cancer. In the modern world, Hornibrook complained, people ate too often and excessively, and relied too much on purgatives, which ruined the bowels. Worst of all, emptying bowels was ‘a matter of shame, to be performed in secret, and at as long intervals as mechanical requirements permit’ (6).

The Culture of the Abdomen is not about cancer, but the possibility of cancer runs as a dark theme through the book: the constipation that comes with civilisation and its bad habits was to blame for cancer. In the modern world, Hornibrook complained, people ate too often and excessively, and relied too much on purgatives, which ruined the bowels. Worst of all, emptying bowels was ‘a matter of shame, to be performed in secret, and at as long intervals as mechanical requirements permit’ (6).

Problems started in infancy, with babies being ‘held out’ (elimination toilet-training) at their carers’ convenience rather than when the child felt the urge. This carried through into youth, where school-masters ‘deemed [time] wasted when spent at stool’ (9). But the body, Hornibrook believed, could be retrained through exercises, posture and habits.

Elmer likely special-ordered the book, which came all the way from Toronto, Canada to small-town Alberta, as suggested by a tag on the inner-leaf for ‘Health Books Supply Co.’ It is not hard to imagine that Elmer was already suffering from early symptoms of cancer—constipation or looseness, rectal bleeding, stomach aches—when he bought the book. Perhaps he, like Hornibrook, put symptoms like constipation down to middle-age and diet. Perhaps he hoped that ‘for a small expenditure of time and trouble we gain efficiency of body, alertness of mind, and a general feeling of well-being’ (54).

I can only hope that when his disease became clear, Elmer didn’t follow Hornibrook too closely in blaming himself:

For the neglect of our bodies, for over-indulgence, for laziness, we have all to pay the price one way or another, and that price is usually a heavy one. (54)

Elmer died young, only in his 30s, and left behind him five children–three of whom were seven or under. His widow never remarried; she died only a few years later, when her heart gave out… perhaps because of the strains of caring for several children on her own. But there is no one left who would have been old enough at the time who could answer these questions: the two eldest sons in the family also died in their 30s from bowel cancer. Elmer’s death has cast a long shadow on the family, more for the heredity of the disease—for which family members are still regularly tested—than for any memories of the father, whose children were too young to really know him when he died.

Elmer died young, only in his 30s, and left behind him five children–three of whom were seven or under. His widow never remarried; she died only a few years later, when her heart gave out… perhaps because of the strains of caring for several children on her own. But there is no one left who would have been old enough at the time who could answer these questions: the two eldest sons in the family also died in their 30s from bowel cancer. Elmer’s death has cast a long shadow on the family, more for the heredity of the disease—for which family members are still regularly tested—than for any memories of the father, whose children were too young to really know him when he died.

The book may not have any markings to indicate Elmer’s usage, but it nonetheless represents our legacy: a culture of the abdomen that still shapes the family today.

October 5, 2016

Japanese “Pillow Books” in the Age of Bric-a-Brac-o-mania

By Elizabeth Emery, Guest Contributor

Recent news reports and opinion pieces lament the emotional stunting of male millennials addicted to violent Internet porn, and propose that things were different when graphic material was harder to obtain and share. Inspired by such thinking, the present installment of “Bric-a-brac-o-mania” flashes back to the 1860s when Japanese shunga, or pillow books, albums featuring couples in fantastically gymnastic or incongruent sexual positions (taking tea, admiring scenery, fetching water, copulating with sea creatures), were all the rage in Paris.

Edmond de Goncourt, one of the trendsetters of the movement known as japonisme expressed delight in 1863 at his acquisition of one such album “of Japanese obscenities,” noting the “violence of their lines, the unexpected nature of the couplings and arrangements of accessories, the whimsy of poses and things, in other words, the picturesque landscape of genitalia” (Journal, October 1863). The “picturesque landscape of genitalia” seems to have haunted him. He later recorded an erotic dream (14 November 1884) where photographer Paul Nadar invited him for a ménage à trois involving a reenactment of scenes from another such Japanese album given to him by Paul Bonnetain (the author of a scandalous 1883 book about masturbation), and he bragged about a visit from sculptor Auguste Rodin who, in a “faunlike” period, studied Goncourt’s “Japanese erotics.” Rodin is said to have reveled in these scenes of “women throwing their heads back, necks breaking, arms nervously extended, feet contracted, all of the voluptuous and frenetic reality of sex, sculptural intertwining of bodies melted and contained in the spasm of pleasure,” a description that suggests the sculptor’s erotic drawings may well have been inspired by shunga (Journal, 5 January 1887; all translations from the French are mine).

[image error]

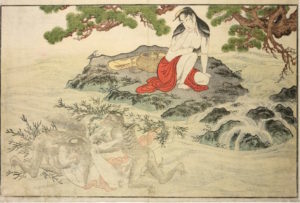

Goncourt would reprise much of the same vocabulary in his book-length studies of artists Utamaro (1891) and Hokusai (1896) where he similarly fixates on violence done to women. He is so troubled by Hokusai’s “Fisherman’s Wife” (also known as Kinoe no komatsu; Figure 1) that he recycles his “painterly” description of this “terrible” and “terrifying” print from one book to the other: “On seaweed-slimed rocks a naked woman’s body, a naked woman’s body [repeated twice in the original], lies passed out from pleasure, sicut cadaver, to the extent that it is impossible to tell whether she is drowned or alive, and whose lower body is being slurped by an immense octopus with frightening black half crescent pupils, while a small octopus hungrily eats her mouth” (Outamaro 136). Fans of the television series Mad Men will recognize this as the print that graced Burt Cooper’s office for several seasons before being gifted to Peggy Olsen as a mark of her success.

Goncourt accurately describes this image, yet his choice of words, with their insistence on nudity, necrophilia, monstrosity, and the ingestion of flesh– major Western taboos– enhances the print’s shock value. By grouping it with similarly graphic descriptions of two other “disturbing” images he further compounds the seeming violence of shunga. The first is a sea scene by Utamaro (the “Abalone Diver”), which he describes as the rape of a sea goddess (138-139).

Rape is once again the subject of his lengthy description of what he labels Utamaro’s personification of Lust, a ghastly “blood-drained” fleshy man “deformed by a spasm of pleasure” (138). Goncourt does not, however, mention the woman’s agency: she fights off her attacker, biting him and telling him to stop.

Goncourt’s obsessive focus on the violent ingestion or possession of women, dead or alive, and his emphasis on the “toadlike” nature of male pleasure, projects his own Western taboos about bodies and sexuality onto an art that modern scholars have shown to have been much more egalitarian in shunga’s own cultural context. Such images may have served an “auto-erotic” function for men and women alike (Screech 23-27), or may have been consulted as fashion guides, for sexual education, or as humorous riffs on mythological tales. The first image, for example, does not chronicle an act of necrophilia; instead it acknowledges the universality of sexual appetites. In the online dossier created by the British Museum in conjunction with its 2013-2014 exhibit, “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese art, 1600-1900,” curators translate dialogue (the characters above the images) showing that the two octopi express their delight that the woman has finally visited them and speak competitively of their sexual prowess. Her initial insults break into graphic onomatopoetic representations of orgasm. Like the second image this one also evokes stories about sensuous women divers from Japanese mythology.

In fact, representations of sexual violence were uncommon in shunga, Goncourt’s obsessive focus on it notwithstanding (the bottom three figures are drawn from an Utamaro album containing twelve prints, but he describes only the most disturbing ones). Sexual violence and tenderness are merely two of several possible models represented across individual albums, many of which, as curators at the British Museum note, seek “to show as many different kinds of coupling as possible, which has the effect of emphasizing the universality of sex.” This includes scenes of solitary arousal as well as the involvement of a third gender, young men known as wakashū, who pleasured (and were pleasured by) men and women alike. In the eighteenth century when shunga albums reached their climax (pun intended), they were distributed massively and without censorship.

Unable to read Japanese captions, Goncourt projects his own violent sexual fantasies on these images, characterizing them as did Rodin in terms of flailing limbs and “epileptic” spasms, thus transforming shunga into a kind of harrowing Eastern counterpart to the sacrilegiously erotic works of Félicien Rops and to the scientific experiments conducted on “hysterical” women by Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpetrière hospital in Paris. Whereas the hideous Japanese depiction of the rapist in Utamaro’s image is intended to condemn the man for his egoism, Rops, like so many Western creators of pornography, blames women for arousing men.

It is no wonder that Goncourt described his albums as “Japanese obscenities” in his Journal. The troubling prose he dedicates to shunga and his careful hoarding of them (Rodin had to seek a special appointment) clearly confirm their pornographic effect on Europeans, as does Ricard Bru’s study of their influence on Western art in Erotic Japonisme. Nonetheless, Goncourt is careful in his published writings to qualify shunga as “art,” likening the “power of the line” in the drawing of a phallus to the Michelangelo sketch of a hand preserved at the Louvre (Outamaro 133-134) or suggesting that Japanese shunga were more alive than “boring” and “perfect” academic Greek art (Journal, October 1863). Such qualifications validated these “pillow books” as collectible items, while making the male perusal of Japanese erotic prints socially acceptable, a bit like rationalizing the reading of Playboy for its essays.

Thanks, in part, to the titillating yet artistic discourse of Western nineteenth-century bric-a-brac-o-maniacs such as Goncourt, Huysmans, Rodin, and many others, shunga albums have been preserved and bequeathed to museums, thus facilitating a massive international vogue for them over the last few years (see the “further reading” below for a few examples of the many recent exhibits and catalogs devoted to shunga). “The division between art and obscene pornography is a Western conception,” says Clark in an interview for the British Museum exhibit. “There was no sense in Japan that sex or sexual pleasure was sinful.” It is the alleged “taboos” emphasized by Goncourt and his contemporaries (violence, bestiality) that transformed graphic and often comical Japanese depictions of the universality of human sexuality into the disturbing and haunting male-dominated “obscenities” he understood them to be.

In fact, the cultural tradition of shunga may have more to offer porn-addicted millennials than just museum exhibits, especially now that entire albums are widely accessible in print and online. Egalitarian in their representation of sexual pleasure and generally free from overt moral judgment, erotic Japanese prints offer remarkable opportunities for discussing mutual consent, variations of human sexuality, and for reminding viewers that the contemplation of erotica is an age-old human activity. The fantastically exaggerated “landscape of genitalia” evoked in shunga also inspires contagious mirth, a socially productive and deflating atmosphere diametrically opposed to the taboos that drive the online demand for porn.

All images © The Trustees of the British Museum in conjunction with the exhibit entitled Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese art, 1600-1900

Further reading

Goncourt, Edmond and Jules de. Journal. Paris: Laffont, 1989.

—. Hokusai. Paris: Bibliothèque Charpentier, 1896.

—. Utamaro. Paris: Bibliothèque Charpentier, 1891.

Screech, Timon. “Shunga: Erotic Art of the Edo Period.” In Ukiyo-e, ed. by Gian Carlo Calza. New York: Phaidon, 2005. pp. 23-29.

Museum exhibits and catalogs by curators

Honolulu Museum of Art, “The Arts of the Bedchamber: Japanese Shunga,” November 23, 2012—March 17, 2013.

Eichman, Shawn, Stephen Salel, and Stephan Jost. Shunga: Stages of Desire. New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc. in association with the Honolulu Museum of Art, 2014.

The British Museum, “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, 1600-1900,” October 3, 2013—January 5, 2014

Gerstle, C. Andrew. Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art. London: British Museum Press, 2013.

Eisei Bunko Museum, “Shunga Exhibition,” September 9, 2015—December 23, 2015.

Screech, Timon. Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan, 1700-1820. London: Reaktion Books, 1999.

Buckland, Rosina. Shunga: Erotic Art in Japan. New York: The Overlook Press, 2013.

Selected works evoking the nineteenth-century Western fascination for Japanese sexuality

Bru, Ricard. Erotic Japonisme: The influence of Japanese Sexual Imagery on Western Art. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2014.

Kawaguchi, Yoko. Butterfly’s Sisters: The Geisha in Western Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Reed, Christopher. Bachelor Japanists: Japanese Aesthetics and Western Masculinities. New York: Columbia University Press, forthcoming November 2016.

Elizabeth Emery is Professor of French at Montclair State University. Author of Romancing the Cathedral: Gothic Architecture in Fin-de-Siècle French Culture (SUNY, 2011), Photojournalism and the Origins of the French Writer House Museum (Ashgate Publishing, 2012), and En toute intimité: quand la presse people de la Belle Epoque s’invitait chez les célébrités (Parigramme, 2015), among other works, she is currently writing a book about nineteenth-century French women collectors of Asian art under the auspices of a 2015 National Endowment for the Humanities grant.

October 3, 2016

St Cuthbert’s Griffin Claw

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

How did the venerated medieval saint Cuthbert (ca. 634-687) of northern England happen to possess not one but two claws of a Griffin, the fabulous lion-bodied, eagle-beaked creature of classical Greek legend?

In fact the saint owned a pair of Griffin eggs as well. These relics were listed in the inventory of the saint’s shrine of 1383. These Griffin claws and eggs later ended up in the Cabinet of Curiosities of Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631). At least one of the claws can now be admired in the British Museum, along with other Griffin-related relics.

St Cuthbert, one of the most influential Celtic holy men of the medieval era traveled, preached, and worked miracles in northern England and southeastern Scotland. He lived as a hermit on a rocky island near Lindesfarne monastery. He died soon after becoming Bishop of Lindesfarne. His body was buried there in an oak coffin but during the violent Viking invasions of the 800s and 900s, the saint’s corpse traveled around the land, disinterred and reburied by monks in several different coffins and sarcophagi. Cuthbert’s remains were laid to rest in Durham in about 882, then removed to Ripon in 995; he was finally reburied in 1104 in Durham Cathedral. His coffin was last opened in 1827. Over the years a cult grew up around his shrine, and Saint Cuthbert accumulated many holy relics of gold, ivory and gems, fine embroidered vestments of Byzantine silk, precious books, exotic artifacts, and costly treasures.

Among Cuthbert’s relics were two “Gryphon claws” and two “Gryphon eggs.” So-called claws and eggs of the Griffin, the fabulous legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and beak of an eagle, were prized in the Middle Ages. Such relics were obtained by pilgrims to the Holy Land and brought back to Europe during the Crusades. The claws were prized as drinking cups because they were believed to detect or even neutralize poisons. The magical claws were usually made from ibex or buffalo horn (Griffin “eggs” were often ostrich eggs, or real fossilized dinosaur eggs).

How did St Cuthbert’s shrine come by such exotic treasures? Alive and then as a corpse, St Cuthbert was certainly well-traveled but he never left the British Isles. The Griffin claws listed in the inventory of his relics in 1383 were likely donated to his shrine in Durham by wealthy followers who obtained them, along with the eggs, during the Crusades of the 11th to 14th centuries. A similar Griffin claw from the Holy Land was displayed in Braunschweig Cathedral, donated by Henry the Lion in the 12th century.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of The First Fossil Hunters, The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World.

September 29, 2016

How I Write History with Patrick Phillips

An Interview with Patrick Phillips

W&M: Blood at the Root tells the story of a county in Georgia that drove out all African-Americans in

W&M: Blood at the Root tells the story of a county in Georgia that drove out all African-Americans in

the early twentieth century. How did you learn about it? And what challenges did you face in writing it?

Patrick Phillips: I first heard the story of Forsyth’s racial cleansing when I was seven years old, from kids on the school bus. My parents had moved to Forsyth from Atlanta, Georgia, and as a new-comer to the county I asked my classmates why there were no black people anywhere. They told me that “a long, long time ago” a white girl had been raped and killed in the woods not far from my house, and that afterwards whites banded together and drove the entire black population out of Forsyth.

I never forgot that story, and had always wondered about the real events that lay behind it, which I have tried to finally tell in Blood at the Root. The greatest challenge I faced in writing the book was finding primary documents and first-hand accounts of something that happened more than a hundred years ago. It turns out that the truth was know-able, but to tell it I had to first assemble documents scattered all over the south, and spend many hours interviewing descendants of the Forsyth refugees. Researching the book felt like a real-life detective story, and I became obsessed with finding clues no one else had ever seen.

W&M: You’re a professor at Drew university. How do you balance writing with your university responsibilities?

Patrick Phillips: That’s a great question! I love teaching at Drew, and feel enriched by my time in the classroom. But of course, books don’t write themselves, and while I sometimes wished that a new chapter would magically appear on my hard drive, it never happened.

Instead, the real magic that helped me finish the book was a sabbatical leave from my teaching duties, and a grant from the Mellon Foundation’s “Arts and the Common Good” program, which helped pay for plane tickets, rental cars, and hotel rooms in Georgia. Without the time off, and without Drew University’s support for my work as a writer, I could never have finished the book.

W&M: You have written poetry and now your new book Blood at the Root is nonfiction. How do you determine which form you write in?

Patrick Phillips: Poetry is my first love, and I’m looking forward to working on poems again soon. But for this project, the last thing I wanted to do was tell the story in poems, because I knew that then people would be able to deny that the racial cleansing really happened, and chalk it all up to “poetic license.” Having grown up with myths, legends, half-truths, and denials about a communal crime that happened in my home place, I knew early-on that this would need to be a work of non-fiction, with iron-clad documentation. There are truths that can best be uttered in a poem, I think, but in this case I was determined to face the facts.

W&M: “Your new book BLOOD AT THE ROOT required a tremendous amount of research. What source materials did you use and how did you gain access to them?”

Patrick Phillips: I spent many years researching the racial cleansing of 1912, and the century of enforcement that followed. I drew on hundreds of surviving documents, and especially contemporary newspaper articles, military reports, letters, land deeds, census records, and maps. I also conducted numerous interviews with the black and white families of “old Forsyth,” because I was determined to fill in some of the gaps in the historical records, which are almost inevitable given that so many of the black refugees were illiterate. As I listened to the voices of the dead, the ones I most desperately wanted to hear were also the faintest.

As far as how I gained access, I drew heavily on digital newspaper archives like ProQuest and Newspapers.com. I used Ancestry.com to make contact with surviving descendants. And many other records I found in the Georgia State Archives, the National Archives, Records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the University of Georgia library, the Atlanta History Center, the Martin Luther King Center library, the New York Public Library, etc. etc.

I guess the best description of my research method is that I greedily sought out (then scanned, photographed, and digitized) every last bit of primary documentation that seemed even remotely related to race in Forsyth County, going all the way back to the Cherokee Removals that took place in the 1830s. It was impossible to know what would prove important later on, since I didn’t have an accurate picture of the events of September and October 1912 until I was nearly done with my research. So along the way, I tried not to worry too much about what was or was not important. I wanted everything.

Patrick Phillips is an award-winning poet, translator, and professor. A Guggenheim and NEA Fellow, his poetry collection, Elegy for a Broken Machine, was a finalist for the National Book Award. His newest book Blood at the Root is available from Norton. Phillips lives in Brooklyn and teaches at Drew University.

September 28, 2016

Bibliophilia: the Extraordinary Library of Catherine the Great

By Susan Jaques (Guest Contributor)

As an unhappily married grand duchess, the future Catherine the Great put her “eighteen years of boredom and seclusion” to good use. A voracious reader, Catherine assembled a large personal library reflecting her broad interests — from history, philosophy and politics to science, travel and art. As she did with Old Master paintings, Catherine II snagged entire libraries, including those of French philosophes Voltaire and Denis Diderot.

Catherine the Great put her “eighteen years of boredom and seclusion” to good use. A voracious reader, Catherine assembled a large personal library reflecting her broad interests — from history, philosophy and politics to science, travel and art. As she did with Old Master paintings, Catherine II snagged entire libraries, including those of French philosophes Voltaire and Denis Diderot.

To seal the 30,000 ruble deal with Voltaire’s niece and heir, Catherine threw in diamonds, furs, and a jeweled box with her portrait. In 1779, twelve large crates containing his 6,760 volumes were unpacked in the Oval Room of the Winter Palace. When Diderot died six years later, his books were installed beside those of Voltaire. Among the art critic’s 2,904 volumes was the only uncensored copy of his masterpiece, Encyclopédie, which Catherine called “indispensable.”

Of the many genres she amassed, it’s no surprise that Russia’s art-loving empress prized art and architecture books. “I am passionately interested in books on architecture. They fill my room and even that is not enough,” wrote the armchair traveler about her trove featuring works by Andrea Palladio and Giovanni Piranesi. Installed at her favorite summer getaway, Tsarskoe Selo, Catherine’s architecture collection proved a valuable resource for her designers, Charles Cameron and Giacomo Quarenghi.

Catherine’s books inspired many of her art commissions. After seeing an exquisite book of engravings by Giovanni Volpato of the Vatican’s Raphael Loggia, Catherine ordered an exact replica for the Winter Palace (see image at right). She couldn’t have her biblical scenes soon enough. Six months into the project, Catherine wrote: “The slightest indigestion of the Holy Father sends me into agonies, for a conclave would delay the work tremendously.” Catherine modeled the Hermitage Library after the Vatican’s, and symbolically moved her book collection below the new Raphael Loggia.

Catherine’s books inspired many of her art commissions. After seeing an exquisite book of engravings by Giovanni Volpato of the Vatican’s Raphael Loggia, Catherine ordered an exact replica for the Winter Palace (see image at right). She couldn’t have her biblical scenes soon enough. Six months into the project, Catherine wrote: “The slightest indigestion of the Holy Father sends me into agonies, for a conclave would delay the work tremendously.” Catherine modeled the Hermitage Library after the Vatican’s, and symbolically moved her book collection below the new Raphael Loggia.

The Hermitage Library’s shelves also included Catherine’s own publications — poems, chronicles, memoirs, plays, opera librettos, magazine articles, fairy tales, a treatise on Siberia, history of the Roman emperors, and a six-volume Notes on Russian History. For her dictionary of comparative languages, Catherine wrote Thomas Jefferson for help translating several hundred words in the Shawnee and Delaware Indian languages; George Washington contributed a translation of Cherokee and Chocktaw words.

By the end of Catherine the Great’s reign, the personal library she’d started as a grand duchess had mushroomed into an encyclopedic 44,000 volumes. In 1795, the year before her death, Catherine approved the design for the Imperial Public Library at Nevsky Prospect. Like her world class art collection, Catherine saw the library as a symbol of enlightened Russia. Today, the Russian National Library is the world’s fifth largest, occupying a city block.

Susan Jaques is the author of The Empress of Art: Catheri ne the Great and the Transformation of Russia (Pegasus Books, April, 2016). She is a member of Historians of Eighteenth Century Art & Architecture and Biographers International and a gallery docent at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

ne the Great and the Transformation of Russia (Pegasus Books, April, 2016). She is a member of Historians of Eighteenth Century Art & Architecture and Biographers International and a gallery docent at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Images:

Empress Catherine II before the mirror, 1779 (oil on canvas), Vigilius Eriksen/ State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia / Bridgeman Images

The Raphael Loggia, State Hermitage Museum, ©Nimblewit, Dreamstime.com

September 26, 2016

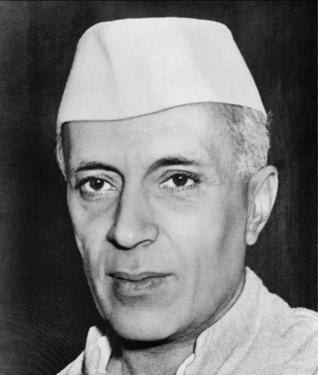

Jawaharlal Nehru: Architect of Independent India

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

In March, 1919, India’s Imperial Legislative Council passed the repressive legislation known as the Rowlatt Acts. The new laws continued the special wartime powers of the Defense of India Act, which had been intended to protect India against wartime agitators, and aimed them at India’s nationalist movement.

At the time the Rowlatt Acts were put in place, Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) was a prime example of the “brown Englishmen” that Thomas Babington Macauley had described as the goal of Western education in India. Educated at Harrow and Cambridge, he practised law with his father, the prominent barrister and nationalist leader Motilal Nehru, and enjoyed a lifestyle that was luxurious by both Indian and European standards. At his father’s urging, Nehru had joined the Indian National Congress on his return from England in 1918 but at first his involvement in the nationalist movement was at best perfunctory.

That changed when Mohandas Gandhi called on Indians to “refuse civilly to obey” the newly passed Rowlatt Acts. In the Sikh city of Amritsar, Gandhi’s call for a national day of work stoppage escalated into a spiral of arrest, protests and violence that ended in the massacre of thousands of Indians who had gather for a religious observance in a public park called Jallianwalah Bagh.

When Nehru overheard General R. H Dyer boasting about his role in the massacre,e he was outraged. He flung himself into the independence movement, touring rural India, organizing volunteers and making public speeches. It was then, he wrote in his autobiography, that “I experienced the thrill of mass feeling, the power of influencing the masses.”

The British imprisoned Nehru for his nationalist activities for the first time in 1921. Arrested nine times, he spent 18 of the next 25 years in jail for his participation in Gandhi’s non-violent non-cooperation (satyagraha) campaigns. He used his time in prison to study and write, transforming himself from a “brown Englishman” into an Indian scholar-politician. He practiced yoga, studied the Baghavat-Gita (and Marxist political theory) and replaced his suits and top hat with clothing made from khadi (homespun).

Gandhi handpicked Nehru as India’s first prime minister, despite substantial differences in their vision of India’s future. They agreed that poverty would be India’s greatest challenge after independence, but disagreed on the solution. Gandhi looked to India’s past for the answer, which he believed lay in self-sufficiency at the village level, with a spinning wheel in every hut. Nehru, whose exposure to what he described as “this vast multitude of semi-naked sons and daughters of India” had led him to the principles of Fabian socialism, looked for national self-sufficiency, based on “tractors and big machinery.” When Gandhi accused Nehru of being unfaithful to his vision of a “harmonious village India”, Nehru countered that he did “not understand why a village should necessarily embody truth and non-violence”.

When India achieved independence from Great Britain in 1947, Nehru became its the first prime minister and minister for external affairs, a dual position he held until his death in 1964. He developed a policy of “positive neutrality” in regard to the Cold War, and served as a key spokesperson for the unaligned countries of Asia and Africa. He committed India to a policy of industrialization, a reorganization of its states on a linguistic basis, and the development of a casteless, secular state.

September 21, 2016

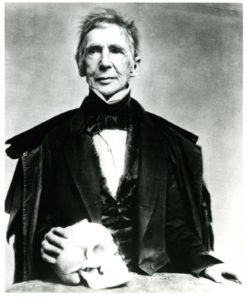

Museum Mysteries: The Flesh and Bones of Dr. John Collins Warren

By Jeffrey Mifflin

John Collins Warren with memento mori, circa 1846.

Dr. John Collins Warren (1778-1856), renowned surgeon and co-founder of the Massachusetts General Hospital, is interred at tranquil Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, Mass.; and he is sequestered in a closed, coffin-like box in storage at Harvard’s Warren Museum. How can that be possible? The disposition of his body was obscure for many years, but recent research has unearthed the facts.

Warren left precise instructions in a letter to his son about what should be done with his “mortal remains after the spirit has quitted them.” He wanted his body taken to Harvard Medical School (where he taught for 38 years) to be “examined or dissected [and] any morbid parts…carefully preserved.” He further instructed that his bones were to be “whitened, articulated, and placed in the lecture room of the Medical College, near [his] bust” as “a lesson useful…to morality and science.” Warren’s skeleton is indeed at Harvard in the anatomical museum that he founded, but his descendants allow the box to be opened only for family members. Dominic Hall, curator of the Warren Anatomical Museum, explains that the historical files have no records of how this came to be, but it is a tradition the museum still honors.

A marker in the Warren family plot at Forest Hills bears the names of several famous medical ancestors of JCW, including Dr. Joseph Warren (who died at the Battle of Bunker Hill) and Dr. John Warren (who co-founded Harvard Medical School). The name “Johannes Collins Warren” also appears, but it was incorrectly assumed by most observers (aware that his skeleton was at Harvard) that the name was merely there as a token of remembrance. My own high school Latin was not equal to the task of translating the inscription on the JCW stone (Animae vestis carnea hoc tumulo conditur), but I now know (with the help of a classicist) that it means: “The fleshy clothing of the soul is buried in this grave.”

Heather Sanders, an administrator at Forest Hills, dug into the institutional archives at my behest to find out more about who is actually buried in the Warren plot. JCW bought the plot in 1852 and pre-arranged for several long-deceased family members buried elsewhere to be exhumed and re-interred in a newly constructed underground vault beside his own morbid parts. The shuffle occurred in August 1856. All of the remains now in the vault are contained in urns—the older ones because they were “repackaged” after decades of moldering in the ground; and JCW’s because the dissection and subdivision of his body made the parts destined for Forest Hills amorphous and compact.

Medical historians and other admirers of the famous surgeon can now locate his “mortal remains” to pay their respects, but one mystery remains: Who determined that his skeleton should remain out of public view?

Jeffrey Mifflin is the archivist of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

September 20, 2016

In condemnation of epigraphs

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Leaf through the opening pages of a book of popular history, and there’s a good chance you’ll encounter an epigraph. Does anyone find value in them?

The epigraph from “In the Garden of Beasts” by Erik Larson

Some of the history writers I most admire — Erik Larson, Harriet Washington, and Diana Preston, to name a few — use epigraphs to introduce their works, but over the years I’ve grown skeptical that epigraphs engage readers, effectively use the valuable real estate that makes up the first pages of any book, or serve any purpose other than showing how resourceful authors are in tracking down literary quotations related to their subject matter.

I have to admit that I once used an epigraph. To introduce my book The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness, I drew from no less than William Shakespeare to include these lines from Macbeth:

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?

I remember how delighted it made me feel to find a short quotation that so neatly suggested the motivations of my biographical subject, the psychosurgeon Walter Freeman, M.D. In retrospect, though, I now see that Macbeth’s question only superficially hints at Freeman’s inspirations, which were dark and complicated. Shakespeare, I’m afraid, offers no big insights into Freeman’s thinking.

I wonder what my readers take away from the quick dip into seventeenth-century drama to which I subjected them. It now seems that my epigraph did no more than boast that I had a passing acquaintance with Shakespeare and assert by tenuous association that my subject was worthy of the attention of someone as brilliant as the world’s foremost playwright.

Reduced to their essential, most epigraphs are simply high-brow celebrity endorsements, given involuntarily by the celebrities who wrote them. “Just as a painting is viewed with greater respect if the canvas bears the name of a distinguished artist,” the archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume wrote, “and as an oft-voiced plan is suddenly adopted when heard from the mouth of a costly consultant, so authors seek stature for their paltry thoughts by quoting someone else.” (And in quoting Hume here, I’m guilty as well.)

Epigraphs make the author feel good, but few deliver significant information, context or even entertainment to readers, who are likely unfamiliar with the subject at hand. I have not included any in the books I published after The Lobotomist. It’s more sensible to use those valuable opening pages to get right into the story and capture the reader’s or browser’s interest from the start.

That means also eliminating or moving those often insufferable prologues, introductions, and acknowledgments that some authors choose to begin their books with, but I’ll spare you that discussion for another time.

The Original Way To Smoke Tobacco Was A Snot-Filled Nightmare

By Robert Evans (Guest Contributor)

One of the oldest written descriptions of tobacco use comes from Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, Governor of Hispaniola (an island near Haiti) describing how the “evil practice” of smoking tobacco looked back in 1535:

“Their chiefs employ a tube shaped like a Y, filled with the lighted weed, inserting the forked extremities into their nostrils. . . . In this way they imbibe the smoke until they become unconscious and lie sprawling on the ground like men in a drunken slumber.”

If you’re anything like me, after reading this paragraph you briefly imagined a world where smokers stagger to and fro, passing out nicotine-drunk and littering our porches and alleys with unconscious bodies. If we still followed the ‘old ways’, that might well be our reality.

But modern cigarettes are made with Nicotiana tabacum, a thoroughly domesticated strain of the plant that averages about 3% nicotine. These old-school Native Americans were probably smoking Nicotiana rustica, which tops out at 9% nicotine. And, of course, they inhaled their tobacco smoke up the nose, through something more like a nasal canula than the cigarettes we know and heavily tax today.

I wanted to know what it had been like to be one of the nose-drunk Native Americans, whose nicotine habit had so offended Governor Oviedo. The Nicotiana rustica was actually easy to find. Drug nerds represent a rather large industry, and you can find wild tobacco for sale on a variety of websites dedicated to selling legal intoxicants most people have no idea even exist. The real trouble was in finding a pipe. This was a problem Amazon.com could not solve.

But I live in Northern California, so of course I know medical marijuana farmers. One of my friends pointed out that the stalks of pot plants have basically the same shape and structure of an old nose-pipe. With some minor modifications, I was able to turn the pot stems into serviceable nose-pipes.

On my first smoke, I tried to stuff the barrel with a small button of tobacco. It felt like snorting a line of ground up fiberglass, but it didn’t get me very high. Governor Oviedo’s description said the nose-pipes had been “filled with the lighted weed”, which made me suspect that the whole pipe might’ve been packed full of tobacco. My nose-pipes were too narrow for this, but after some trial-and-error I realized that I could roll a cigarette and stick that in the end of the nose-pipe.

My eyes watered. My nose burned. After a half-dozen puffs, I was so light-headed I had to brace myself against a wall to keep standing. I nose-smoked that entire wild tobacco cigarette, and by the end of it I wouldn’t have trusted myself to operate a toy car. The best way I can describe it is ‘nicotine drunk’. It was a high much more intense than I’ve ever gotten from hookah, and so different from a normal cigarette that it might as well be a different drug.

My eyes watered. My nose burned. After a half-dozen puffs, I was so light-headed I had to brace myself against a wall to keep standing. I nose-smoked that entire wild tobacco cigarette, and by the end of it I wouldn’t have trusted myself to operate a toy car. The best way I can describe it is ‘nicotine drunk’. It was a high much more intense than I’ve ever gotten from hookah, and so different from a normal cigarette that it might as well be a different drug.

The high was powerful- not fun. My sinuses felt coated in tar and I had that queasy, hollowed-out feeling in the pit of my belly for several hours. It was a valuable reminder that, for the earliest smokers, tobacco wasn’t a casual habit, it was a Capital D-rug. One with the power to profoundly change a user’s state of mind, and burn a hole through his sinuses.

Robert Evans is an editorial manager at Cracked.com. His  articles rack up an average of sixty-four million views a year. He was a contributor to the bestselling You Might Be a Zombie and The De-Textbook. Now, his new book A (Brief) History of Vice is available from Penguin Random House.

articles rack up an average of sixty-four million views a year. He was a contributor to the bestselling You Might Be a Zombie and The De-Textbook. Now, his new book A (Brief) History of Vice is available from Penguin Random House.

September 19, 2016

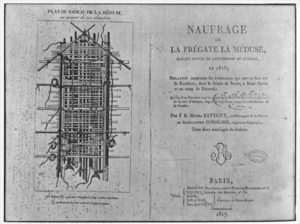

Falling Off the Raft of the Medusa

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Two hundred years ago, in July 1816, a French Navy frigate named La Méduse was wrecked off the coast of Mauritania. On board were passengers headed for Africa for an array of reasons –soldiers in the colonial army on a mission to reconquer Senegal, settlers, scientists, adventurers. Its captain was an inexperienced naval officer who had been appointed to the post as a political favor. His poor judgment resulted in the ship’s foundering on a sandbar.

It was the age of shipwrecks. But this one became notorious almost immediately. It was a political scandal for the newly restored French monarchy because of the inexperienced captain and his crew. Survivors recounted chaos on board, undisciplined evacuation, sailors boarding the lifeboats and leaving passengers behind. But the worst part of the story was the tale of the hastily built wooden raft that was put into the water with 146 men and one woman on board, It was initially towed by one of the smaller boats, but then cut adrift when the job became too difficult for the oarsmen. On the raft, there followed savage episodes of mutiny, murder, and cannibalism. After two weeks, what remained of the raft was plucked out of the water by a passing ship. There were 15 survivors on board.

It was the age of shipwrecks. But this one became notorious almost immediately. It was a political scandal for the newly restored French monarchy because of the inexperienced captain and his crew. Survivors recounted chaos on board, undisciplined evacuation, sailors boarding the lifeboats and leaving passengers behind. But the worst part of the story was the tale of the hastily built wooden raft that was put into the water with 146 men and one woman on board, It was initially towed by one of the smaller boats, but then cut adrift when the job became too difficult for the oarsmen. On the raft, there followed savage episodes of mutiny, murder, and cannibalism. After two weeks, what remained of the raft was plucked out of the water by a passing ship. There were 15 survivors on board.

For the French, the events of the Medusa shipwreck became emblematic of a disintegration of the values of discipline, honor, and simple humanity in a culture already crushed by the Napoleonic wars. The painter Théodore Géricault produced an enormous painting of the raft. To those who viewed it as it was shown in Paris and London, the monumental work seemed to symbolize a battered humanity, reaching desperately for a distant hope represented by the tiny ship on the horizon.

Géricault was not interested in producing a realistic representation of the disaster, but he was obsessed by the event and the published narrative that had been written by two survivors, Alexandre Corréard and Henri Savigny. He closed himself up in his studio for months and made numerous studies of human bodies thrown together, using live models but also cadavers and body parts that he acquired from the morgue. He interviewed Corréard and Savigny. The resulting painting had a huge impact and was immediately controversial. Some considered it almost treasonously humiliating as a representation of the French.

Géricault was not interested in producing a realistic representation of the disaster, but he was obsessed by the event and the published narrative that had been written by two survivors, Alexandre Corréard and Henri Savigny. He closed himself up in his studio for months and made numerous studies of human bodies thrown together, using live models but also cadavers and body parts that he acquired from the morgue. He interviewed Corréard and Savigny. The resulting painting had a huge impact and was immediately controversial. Some considered it almost treasonously humiliating as a representation of the French.

Every one of the passengers who had the misfortune of being put on the raft had a story. But the one story that may have been the most painful emblem of the breakdown of French civilization was one that remained anonymous. It was the story of the lone woman on the raft. Her history, if not her name, had been told by Corréard and Savigny, but somehow it remained an unspoken detail in the public discussions of the disaster. A detail perhaps almost too horrible to be repeated. To this day, it is a detail that has been forgotten.

She was not to be one of the survivors. But she fought for her life. She was traveling with her husband, and had served 20 years with the French armies as a ‘cantinière’, a woman who carried supplies and prepared food for the soldiers. We can assume she  was physically strong. She was reported to have argued for her own survival on the basis of her strength and potential usefulness in support of her fellow passengers. But she was thrown off the raft along with others deemed too weak to last – not once, not twice, but three times over a 12-day period. The last time, she had fractured her leg when it was caught between two boards.

was physically strong. She was reported to have argued for her own survival on the basis of her strength and potential usefulness in support of her fellow passengers. But she was thrown off the raft along with others deemed too weak to last – not once, not twice, but three times over a 12-day period. The last time, she had fractured her leg when it was caught between two boards.

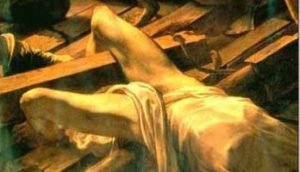

We know that Géricault thought about depicting a female figure on his raft, if only, possibly, a dead one. He included studies of female bodies in his preliminary sketches. And he knew the story, having read and interviewed Corréard and Savigny. To me, one of his preliminary versions of the painting is very suggestive of the story of the doomed cantinière and her husband. It shows a man collapsed in the center of the raft grasping a long piece of fabric that trails off into the water.

In the final version of the painting, this fabric has become a transparent covering of a body whose head is below the surface of the water, hidden from view. Could this body be female? It looks muscular, but also somehow feminine – at least one art critic (Michael Glover) has commented that he thinks it is a woman. The body is trapped, half on, half off the raft – by one leg , caught between two boards.

In the final version of the painting, this fabric has become a transparent covering of a body whose head is below the surface of the water, hidden from view. Could this body be female? It looks muscular, but also somehow feminine – at least one art critic (Michael Glover) has commented that he thinks it is a woman. The body is trapped, half on, half off the raft – by one leg , caught between two boards.

Look closely. What do you think? Did Géricault want to suggest the story of the unfortunate cantinière?