Holly Tucker's Blog, page 13

August 1, 2016

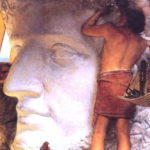

Roman Emperor Tiberius and the Giant Tooth

By Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

A unique record of a purposeful paleontological investigation of a large vertebrate fossil was carried out by the Roman emperor Tiberius. During Tiberius’s reign (AD 14‑37), a violent earthquake utterly devastated several cities of Asia Minor. According to Phlegon of Tralles, who had access to the imperial archives and other writings now lost, the damage was especially severe in Pontus on the Black Sea (now Turkey). Pliny the Elder commented that this was “the worst earthquake in human memory, destroying twelve cities in one night.”

The earthquake opened cracks in the earth, exposing vast skeletons. Phlegon reported that the survivors “were reluctant to disturb the bones,” believed to belong to ancient heroes from the days of myth. “But they decided to send an enormous tooth from one of the skeletons to Tiberius.” Ambassadors from Pontus carried the great molar, about 12 inches long, to Rome.

The envoys asked the emperor if he wished to have the rest of “the giant hero.” Eager to know the creature’s full size and form, but nervous about desecrating what might be a hero’s grave, Tiberius devised “a shrewd plan.”

He hired a “geometer” named Pulcher to make a model of the giant based on the tooth. According to Phlegon, Pulcher sculpted a head proportionate to the size and weight of the tooth. Then the mathematician estimated how large the entire body would have been. Pulcher’s replica, presumably a grotesque humanoid bust of clay or wax, pleased Tiberius.

This ancient narrative is more than just an anecdote about Tiberius’s clever response to a provincial embassy. The facts are historically and scientifically sound: The Black Sea region is prone to strong earthquakes which do expose gigantic skeletons of extinct mastodon, steppe mammoth, and Elasmotherium (giant rhinoceros). In his work “On Earthquakes,” Theopompus of Pontus described a quake on the Taman peninsula between the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. In that case, the earthquake “tore open a ridge and disgorged immense bones” whose “skeletal structure measured 24 cubits [34 feet; 10 meters].” The size of the giant tooth (about 12 inches) transported to Tiberius corresponds to the length of the molar of a steppe mammoth.

Tiberius generously rebuilt the destroyed cities in Pontus. In gratitude, the ambassadors dedicated a bronze statue of a giant in the Temple of Aphrodite in the Roman Forum. It seems likely that the giant tooth may have been part of the dedication. Unusual relics from the provinces were routinely sent to Rome, and a hero’s tooth would be an especially suitable tribute at the dedication of a giant statue. Emperors often commissioned replicas of items of interest and colossal statues were extremely popular in Rome at that time. The imperial mathematician’s extrapolation of the “hero’s” stature from a single tooth is not far‑fetched: paleontologists today use a lower first molar to give a good indication of a mammal’s total body size and weight.

Phlegon’s long-neglected account of the giant tooth is the earliest written record of a scientific reconstruction of a life‑sized model from prehistoric animal remains.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths and Myths in Greek and Roman Times; The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World.

July 25, 2016

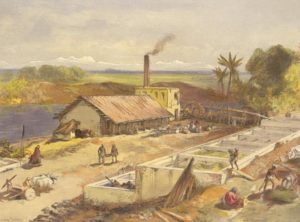

The Blue Mutiny

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

William Simpson. Indigo Factory in Bengal. 1867

Save

In the fall of 1859, two years after the violent uprisings in Northern Indian known as the Indian Mutiny or Sepoy Rebellion, thousands of peasant-farmers (ryots) in the Indian province of Bengal refused to accept cash advances to plant indigo crops in the spring, an act of resistance that became known as the Blue Mutiny.

An Industry Built on Oppression

Property laws in Bengal had put European indigo planters in conflict with ryots ever since commercial indigo growing was introduced to Bengal at the end of the eighteenth century. Europeans were not allowed to own land, so planters had to contract with ryots to grow indigo for them in the ryots‘ fields.

From the first, ryots were reluctant to grow indigo, which was sown and harvested at the same time as rice, their primary food crop. Planters used both trickery and violence to force unwilling ryots to plant indigo. Some forged contracts. Others resorted to beatings, looting, arson, kidnapping, and even murder to force ryots to accept cash advances.

Once a ryot had accepted an indigo contract, willingly or not, he received a cash advance in the fall to plant indigo the following spring–a system similar to sharecropping in the American South after the Civil War, with many of the same inherent pitfalls for the farmer. In theory, the ryot would repay his advance and make a small profit after harvesting his indigo. In bad years, expenses exceeded advances and ryots went in debt to planters. Even in good years, planters often did not pay ryots what they were owed at the end of the growing season. Many used the threat of unpaid debts to force ryots to continue planting indigo year after year.

Ryots had little recourse against the planters, who were supported, both officially and unofficially, by British officials. Isolated outbreaks of violence against planters and indigo factories occurred as early as 1809, but were quickly suppressed by the police. On the rare occasions when ryots took the expensive and difficult step of going to court, magistrates generally supported the planters.

The Ryots Push Back

The system was inherently unstable: profits depended on both prices on the world indigo market and good crop yields. In the 1830s and 1840s, crops were good and “Bengal blue” dominated the world indigo markets. From 1847 through 1858, bad weather reduced the average annual indigo crop yield by 23% compared to the previous decade. While indigo profits dropped, market prices for jute, linseed, and rice rose, making indigo contracts even less appealing to ryots.

At the same time, the relationship between government official and planters was disrupted. In 1858, in response to the Indian Mutiny, the British Crown replaced the East India Company as India’s ruler. Crown rule brought administrative changes at every level of the government. Smaller district divisions made it easier for ryots to bring their complaints to court. More importantly, young magistrates, hired under a system of competitive examinations, occasionally ruled in favor of ryots in disputes between ryot and planter. Word spread that the government would not force ryots to grow indigo.

When ryots refused to accept indigo advances in 1859, planters reacted the way they had in the past, leading armed bands to force ryots to accept the advances. This time, some villages fought back.

Over the course of the next two years, violent responses to planter oppression spread throughout Bengal. Both planters and ryots appealed to the government for aid. Ryots flooded officials with petitions for relief from specific planters’ abuses. Planters called for laws that would make breaking an indigo contract a criminal offense. The courts overflowed with indigo cases.

In 1860, the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal appointed a commission to investigate conditions in the indigo industry. For four months, members of the Indigo Commission heard testimony from every group with an interest in indigo. The Commission’s final report described an industry built on violence, coercion, and oppression, but the Commissioners were not able to agree on solutions and the government took no action.

A Temporary Peace

By the middle of 1863, uneasy peace had been restored to the indigo districts, largely as a result of the resolution of hundreds of indigo cases in the courts that exposed planter abuses and clarified ryots’ rights. Pressured by public opinion, some planters re-negotiated their relationships with ryots; others gave up indigo entirely.

Improved relations between planters and ryots were not permanent. When aniline dyes threatened to destroy the indigo industry, planters put new pressures on their workers. In 1916, Indian indigo workers once again protested the conditions under which they lived and worked, led by a young activist named Mohandas Gandhi.

July 19, 2016

How Dry They Were: A Century Ago, Members of the Prohibition Party Had High Hopes for Their Convention

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

“Only four of us here and not a thing to do but keep awake,” a St. Paul, Minn., policeman complained in July 1916, during the national convention of the nation’s oldest third party. “This sure is the most orderly bunch I ever saw.”

Suffragist Elise Hill speaking to a crowd during the Prohibition Party convention, St. Paul, 1916

There were no smoke-filled rooms, no delegates carousing late at night. These conventioneers, gathering to nominate their party’s candidate for president of the United States, were neither Republicans nor Democrats. They represented the Prohibition Party, and they aimed to abolish the sale and consumption of liquor in America.

Founded in 1869 in Chicago, the Prohibition Party had fielded candidates in eleven presidential elections before 1916. The most successful, John Bidwell, collected 263,000 votes in 1892. But the party had never come close to placing a nominee in the White House or even carrying a state.

Party members viewed the 1916 convention as especially important. Prohibition already existed in many states, and a nationwide liquor ban seemed inevitable. With its main goal nearly achieved, the party faced the possibility of extinction.

The national committee scheduled its 1916 convention for July 19-21 in St. Paul, the furthest west the party had ever gathered. Its leaders held no illusions of outpolling the Republicans or Democrats in the election, but they hoped to snatch third place away from the Socialists and tally 1 million votes — four times as many as they had ever received.

Meanwhile, the local Prohibition Party committee procured for visiting delegates 7,200 bottles of drink—nonalcoholic grape juice, of course.

On July 18 trains in the St. Paul depot began disgorging the 658 delegates and 19 alternates — a peculiar assortment of men and women from 47 states, with the largest contingent from California. Among them were Charles Randall of California, the only Prohibition party congressman; the Rev. L.G. Jordan, a former slave on the plantation of Confederate president Jefferson Davis; a reformed criminal from New York known only as Convict 11.221; and Dr. A.D. Bridgman of Illinois, who attended all convention functions wearing a long black frock coat and silk top hat: “I declaim that it is proper convention regalia,” he said.

The following day, the convention delegates got down to the business of picking a presidential candidate. They chose J. Frank Hanly of Indiana on the first ballot. Placed in nomination for vice-president was Marie C. Brehm, a prominent Women’s Christian Temperance Union activist from Chicago — the first woman ever nominated for the ticket of a national political party. But Ira Landrith, a veteran prohibitionist from Tennessee, won final approval as Hanly’s running mate.

The convention disbanded and the delegates left St. Paul with high hopes of reaching 1 million votes and carrying one or two states. Prohibition sentiment was high, the party had taken strong stands on other issues, and its candidates were on the ballot in 44 states. How could they miss?

They missed. The Hanly-Landrith ticket received only 220,000 votes, barely 1 percent of the total. It was no surprise that Woodrow Wilson trounced them, but quite a humiliation that A.L. Benson, the Socialist candidate, out-polled them three to one.

On the national scene, the Prohibition Party never recovered from the campaign that began with its St. Paul convention. Its influence dimmed once Prohibition won ratification in 1919 and remained low after laws banning alcohol sales were repealed in the 1930s. The Party’s 2012 candidate for U.S. President received only 518 votes, and its 2016 candidate, Jim Hedges of Pennsylvania, won the Party’s nomination not at a convention, but by conference call.

Further reading:

Koerner, Brendan. “What Do They Serve at a Prohibition Party?” U.S. News and World Report, July 12, 1999, Vol. 127(2), p. 51.

Storms, Roger. Partisan Prophets: A History of the Prohibition Party, 1854-1972.

July 18, 2016

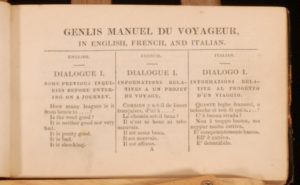

Life on the Road, in the Age of Napoleon: A Guidebook by Madame de Genlis

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Madame de Genlis by Adélaide Labille-Gulard

Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis, born in 1746, was a writer, accomplished musician, and tutor to the children of a member of the French royal family, the Duc d’Orléans. She was an innovative teacher, developing modern methods of applied and practical learning, in contrast to the conventional reading program in Latin and the classics. She wrote plays and fiction to help children reenact historical lessons and she taught her pupils botany by taking them on field trips.

Travel of all kinds became, in her view, one of the best forms of education. She herself had more opportunities to travel than she could ever have foreseen, beginning with an abrupt flight from Paris during the Revolution. In 1793 both her husband and her employer the Duc d’Orléans were guillotined. She fled to England and then Switzerland with one of her pupils, Mademoiselle d’Orléans. She then lived in Germany for a time before returning to Paris in 1800. After this she supported herself by writing essays, novels, plays, children’s literature, and memoirs.

While she was in Berlin she also wrote a practical guide for voyagers, aimed at readers who were new to travel, including women of all ages, such as mothers with young children. The little ‘Traveler’s Manual” was also a language textbook. Genlis published it as a bilingual guide in French and German. It was quickly reprinted with added translations of her ‘traveler’s dialogues’ in Italian, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian.

While she was in Berlin she also wrote a practical guide for voyagers, aimed at readers who were new to travel, including women of all ages, such as mothers with young children. The little ‘Traveler’s Manual” was also a language textbook. Genlis published it as a bilingual guide in French and German. It was quickly reprinted with added translations of her ‘traveler’s dialogues’ in Italian, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian.

Not surprisingly, many of the dialogues instruct travelers how to deal with unpleasant surprises, such as illness, accident, or encounters with untrustworthy people. She also includes model letters for readers contemplating settling in for a lengthy stay abroad: notes to bankers, conversations with landlords, merchants, postal messengers, and stable masters. Her most detailed model dialogues are the ones dealing with questions about a country property to rent. To me, these dialogues inquiring about gardens, stonework, bedrooms, windows and and gates reflect her own dreams of the perfect country retreat, in an age when violence and danger must have seemed inescapable.

The Village of Waterloo by George Jones

The manual includes some useful phrases to be used by conquering soldiers. The experience of having military personnel arrive in one’s home (or being a soldier invading a home) was common enough to warrant a model conversation. Here is one proposed phrase (wishful thinking, it seems to me):

– Don’t fear anything, we are Englishmen, Germans, Russians, Frenchmen etc. Our national character and the obedience we owe to our sovereign, are a double pledge of our generosity. A subdued enemy is considered by us as an unhappy friend.

And here are a few excerpts for more mundane occasions:

A Lady, with Children, arriving at an Inn:

-Is this cradle clean?

-Let us see if there are any bugs in it.

– Take it out into the passage, or yard and shake it out well, wash it well, and then bring it to me again.

Speaking to the hairdresser:

-Pray cut and curl my hair. Make the curls large so that it is is done sooner.

-First comb my hair. Gently!

-Make the irons hot. Is it too hot? Try it first on paper.

-This curl is not large enough.

-Where is the powder box and pomade?

-Please powder me. (Or, I do not wear powder.)

Phrases for getting to know strangers or describing them to others:

-Is he or she your friend?

-He is ill.

-He is going to be married.

-He is a widower.

-He has fought a duel.

-He was killed.

-He was wounded.

-Is he dangerously wounded?

-He has ruined himself.

-He is a gamester.

-Is she aimiable? Has she any talents? Is she rich?

In case of Fire:

-Fire! Fire! The house is on fire.

-Go and fetch the fire engine. Fill the buckets with water. Make a chain.

-Is the fire out?

-Do not be frightened madam, the fire has caught your gown. Do not move, stay where you are, lay down upon the floor, you must stop the fire with your hands.

-Lay upon that canopy, upon that bed, stop the fire with that pillow.

-The fire is stopt. My hands are burnt. Put honey or grated potatoes on them.

For further reading:

Manuel du voyageur, or, The traveller’s pocket companion: in six languages, consisting of familiar conversations in English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, together with models of letters, notes, etc., by Stéphanie Félicité Genlis, comtesse de. London, 1816.

(There are several editions available on Google Books.)

July 13, 2016

Museum Mysteries: Funny-Looking Scissors and the Empire State Building

By Tegan Kehoe

Often, the best way to solve a museum mystery is to go straight to the source. In March, the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital received a wonderful donation of items related to cardiac surgery through the years, as we prepared for an exhibit on the topic. The donation included a number of highly specialized surgical tools. It was clear that in each pair of scissors and forceps, the precise size, curve, and direction of the tip was important, but our team didn’t know what the tools were called or what they did. The usual print sources, such as medical textbooks and supply catalogs, didn’t clear up these differences. If these had been antique tools, we might have been stumped. Luckily, they were used within living memory. A senior surgeon at MGH was kind enough to help us out. As it turns out, some of the names were surprisingly silly.

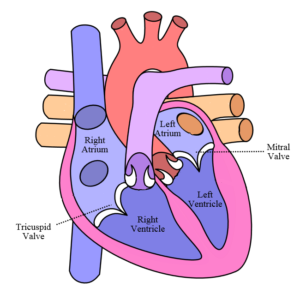

Differently shaped valves call for differently shaped tools. Image adapted from Wikimedia Commons, original artist unknown.

One of the first puzzles was a pair of implements that look like tools a dentist might use to keep your cheek out of the way while working on a back molar. At first glance, the two tools look identical, or like a mirror image of one another, but almost every angle is different. It turns out that one is a mitral retractor, and the other is a tricuspid retractor. They are a lot like that tool at the dentist, in that they keep a piece of tissue spread back and out of the way during a procedure. Each one can be clamped into a metal frame that rests on a patient’s chest. The mitral retractor is used on the left side of the heart, and the tricuspid retractor on the right, each between the top and bottom chambers (left or right atrium and ventricle). So, these two tools would be mirror images of each other, except that the heart is not symmetrical.

It seems that the names for some of these tools are either too long, or too boring, for some surgeons, and each team develops their own language. Metzenbaum scissors, which are used to cut delicate tissue during organ operations, are nicknamed “bombers.” Chest scissors become “chesties,” and a pair of “funny looking scissors” was dubbed “funnies.” J. Gordon Scannell, MD, who performed Mass General’s first heart surgery in 1951 and first open heart surgery in 1955, was responsible for one of the nicknames. He had brought back a particular surgical clamp after a trip to England, and always referred to it as his clamp. Because the others in the OR heard him call it “my clamp” so often, they started calling it “the my clamp.”

Some notes on what’s what.

During an operation, all of the tools that the team will need are usually prepared and placed in the area considered the sterile field, so that no one has to leave the sterilized space during a procedure. One of the most fun tool nicknames was for a particular suction pump. Suction is used to clear excess fluid (usually blood) so a surgeon has a clear view of an operation. One time, a surgeon couldn’t remember the name and got testy when the scrub corrected him. He said, “I don’t care if it’s called the Empire State Building, when I am doing a mitral valve, I want it on the field.” Naturally, it has been known ever since as the Empire State Building among the people who were there and their colleagues.

If you’re in Boston, stop by the Russell Museum to see our exhibit on cardiac surgery. The tools described here aren’t on display – some of them were displayed in a pop-up exhibit we did for an event – but you can see an early heart-lung machine and more.

Tegan Kehoe is the exhibits and education specialist at the Russell Museum.

July 11, 2016

Living in interesting times: when history happens

By Helen King (monthly contributor)

The old Chinese curse goes ‘May you live in interesting times’. And for those of us in Britain, the times seem to become more ‘interesting’ by the moment. The referendum decision for ‘Brexit’, which seems to have taken by surprise even those who were campaigning for it, raises many questions about what happens next. When will Article 50 be activated and the process of leaving the EU really begin? And on what terms would that be? As some who voted Leave now protest that they hadn’t understood what that would mean, and as many people didn’t bother to vote (or weren’t allowed to because they aren’t citizens), should there be a second referendum? How can Britain simply pull up the drawbridge and ignore Europe, when we have so many EU citizens resident in England, Scotland, Wales and N. Ireland? What about British citizens who’ve taken advantage of freedom of movement to live and work elsewhere in the EU? What about Scotland’s desire to Remain, at odds with that of England, and what about the relationship between peace in Ireland and the “soft border” between the north and the south?

And just when it seemed like it couldn’t get any more complicated, the Prime Minister announced his resignation, meaning that someone else will have to take Brexit forwards; an obvious contender withdrew; and the opposition Labour Party moved to self-destruct mode. At one moment, we were seeing the referendum as a decisive event in Boris Johnson’s inexorable rise to be Prime Minister: at the next, we were rewriting the story to make it part of his fall.

Can history help?

At this point, many people are looking at history in the hope of finding some perspective. For starters, as an ancient historian by training, I find myself thinking of the Roman Empire. The English Channel felt like a huge obstacle to the Romans when they tried to expand their empire to include what they called Britannia. Yet for the British tribes, that water had long been an opportunity to expand their trade networks. People on both sides of it were part of the same tribes: it was a connection, not a barrier. When Julius Caesar crossed the Channel and invaded Britain, did it feel like a historical change to the British tribes? Because it wasn’t; it was nearly 100 years before the emperor Claudius repeated the invasion and imposed any form of Roman government on the island. Writing between Caesar’s invasion and Claudius’ conquest, the geographer Strabo argued that, financially, it really wasn’t worth the trouble of conquering Britain.

And what about the bigger questions? How do we know whether this is really the end of the world as we know it? What does a turning point in history look like? How do we know one when it happens? It’s very hard to know what is going on while you’re actually in it, and maybe just as hard to know how historians looking back on today’s events in 50 or 100 years will assess them. In the run-up to the referendum, the killing of Labour MP Jo Cox felt like it was a turning point: but, was it? Who turned, and in what direction?

It’s often pointed out that nobody living through The Hundred Years War had any idea it would go on so long (and it lasted more than 100 years in any case). The assassination of Franz Ferdinand ‘started’ the First World War, but would it have happened in any case? The ancient historian Thucydides distinguished between underlying causes and immediate causes of war – suggesting that, if the underlying cause is already there, then a pretext will come along in due course. At the moment, we have no idea whether the rise in reports of racial hate in the aftermath of the referendum will prove to be a blip, or will be recorded as part of a wider rise in racism across Europe.

Turning to fiction

All this makes me reflect on how very difficult it is to write historical fiction, because it means trying to forget what we know happened next, and instead to see events through the eyes of someone living at the time. I think the current situation has given us a better sense of just how terrifying uncertainty can be. Maybe one of the problems right now is that we hear too many voices, in news reports and on social media. In the past, most people would have had no idea what was going on, hearing of political events weeks or months after they happened. Can we reconstruct what it was like for them to live through events which turned out to be turning points in history?

It’s the English novelist Ian McEwan who, in my opinion, has written the best analysis of the current uncertainty, likening us now to servants discussing the situation below-stairs, hearing above our heads the footsteps of the above-stairs people but not knowing what they mean. Taking up his words, has Britain changed utterly, or is this all a bad dream? And how long will it be before we can answer that?

And then there’s the ancient Chinese curse. Actually, there isn’t. As far as I’ve been able to discover, it isn’t Chinese and it isn’t ancient. Even that ‘fact’ proves to be slippery!

July 8, 2016

French or Phở?

By Michael Garval (Regular Contributor)

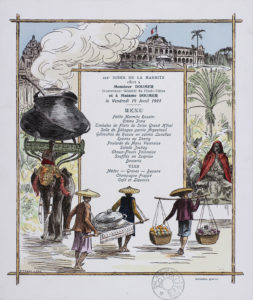

What’s in the big pot or marmite, in this 1901 French illustrated menu, with its colonial Indochinese setting? Maybe pot-au-feu, the celebrated French comfort food of boiled beef and vegetables? Or perhaps phở (pronounced “fuh”), the celebrated Vietnamese comfort food of beef broth with rice noodles? And what might such possibilities tell us, about both culinary and colonial history?

Franc-Lamy (Pierre Franc Lamy, known as) banquet menu, April 19, 1901, 222e Dîner de la Marmite, offert à Monsieur Doumer, Gouverneur Général de l’Indo-Chine, et à Madame Doumer (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris).

Mystery Marmite

Marmite derives from an Old French word meaning “hypocritical,” because the deep, covered pot coyly hides its contents. La Marmite was also an exclusive turn-of-the-century Parisian literary and artistic association that held regular banquets, whose handsomely illustrated menus would incorporate emblematic, enigmatic marmite motifs.

Pierre Franc Lamy illustrated this particular menu for a dinner honoring then Colonial Governor of Indochina and future French President Paul Doumer. The central bill of fare, offering classic French banquet food and fine wine, contrasts with the surrounding Indochinese imagery. Indeed the whole menu juxtaposes colonizer and colonized, their worlds, and especially their food.

The governor’s palace, in the distance, could represent power behind the scenes, controlling this colonial realm. But the building seems almost lost in the background. A bustling Saigon street scene dominates the foreground, as porters in native garb carry local foodstuffs, seemingly unrelated to the Gallic fare served Monsieur Doumer.

Souvenir de Saigon. Palais du Gouverneur Général. French colonial postcard of the Governor’s Palace in Saigon, sent in 1902.

An elephant transports a giant, steaming cauldron, the hallmark marmite on each of the association’s banquet menus. But this one’s emphatic curves lend it a far eastern air. Given the pot’s distinctive appearance, placement on a Saigon thoroughfare, and proximity to other homegrown offerings, we infer that it contains local food as well.

Despite the colonial setting, we glimpse the possibility of indigenous food—and people—prevailing. Steam from the marmite, carrying the aromas of local cuisine, already partly obscures the Governor’s palace, promising to erase this colonial icon from view, and prefiguring the faraway power’s exit from the scene a half century later. Perhaps unwittingly, this menu offers a premonitory vision of decolonization.

Still, what’s in the marmite? The menu lists “Petite Marmite Rossini,” a fancified take on homey pot-au-feu, enriched with foie gras, truffles, and demi-glace. But this is a far cry from local street food, and the gigantic pot is far from petite. Wouldn’t it make more sense to imagine this mystery marmite filled with phở?

Faux Phở

Over the past century, in Vietnam and then around the world, phở has come to be seen as the quintessential Vietnamese dish. These days, imitations, interpretations, and bastardizations abound. Hanoi-based French chef Didier Corlou experiments with foie-gras enhanced phở, a latter-day Indochinese Petite Marmite Rossini. Even TV chef Rachael Ray prepares “Phunky BBQ Pho,” repeatedly mispronouncing phở as “faux.” Faux phở indeed: concocted from chicken stock, angel hair pasta, and pork shoulder, and reviled by Vietnamese-American commentators as an affront to their heritage.

So what is phở, and what’s its history? A soup of rice noodles, herbs, and spices in a rich, flavorful beef broth, phở originated in the early twentieth century, in or around Hanoi, in the north. Beef had not figured much before in Vietnamese cuisine, as cattle were largely beasts of burden. But French colonizers demanded steaks and roasts, leaving bones and scraps that thrifty local street food vendors started using for soup. The name phở may even derive from the French feu or fire, as in pot-au-feu. Or it may derive from fen or fun, the Chinese word for noodle, and seasonings like star anise and ginger come from China as well. These influences aren’t surprising, since the Chinese ruled Vietnam for over 1,000 years, long before the French colonized it for less than 100.

TONKIN–Hanoï–Un Coin du Marché. French colonial postcard of a Hanoi street market, sent in 1906.

For the first half century or so of its existence, phở remained a regional specialty, little known outside the north. But with the 1954 Geneva Accords, which split Vietnam in two, nearly a million northern refugees arrived in the south, and began selling their hallmark soup. Phở soon took on the mantle of a national dish for the divided nation. In turn, in the wake of the Second Indochina War, with refugees flung far beyond the country’s borders, the Vietnamese diaspora would spread phở across the globe. For better or worse, phở has now become an international dish, in the same dubious pantheon as pizza, paella, or sushi: ubiquitous, much loved, but oft misconstrued, while purists still prefer the more austere northern version. And certainly in 1901, in our menu’s day, no sort of phở yet existed on Saigon streets, or elsewhere in the south.

Simmering Tensions

Ultimately then the mystery marmite contains no tangible, identifiable dish. Instead, the steaming pot proffers some vague, nostalgic, ahistorical ideal of simple, slow-cooked, homespun goodness, at odds with both the menu’s refined banquet food, and its complicated colonial context of tensions and shifts, exchanges and interconnections. But at the same time as this menu was created, a real dish was emerging, its multi-layered flavors interwoven, over time, with Vietnam’s complex, fraught, fascinating legacy of colonization, decolonization, division, and diaspora. So the next time you tuck into a steaming hot bowl of phở, savor the delicious taste of history.

July 6, 2016

The Emperor’s Status Update: Introducing the Carte de Visite

By Rachel Mesch

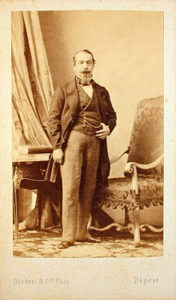

In May of 1859, Napoleon III headed across French borders to help push the Austrians out of Italy. But first, he stopped to have his picture taken.

Disdéri’s portrait of Napoleon III

Legend has it that on his way to the Italian front, the emperor of France stopped at the studio of Eugène Disdéri, the soon-to-be legendary photographer who had patented a technology five years earlier enabling him to produce multiple photos by using eight negatives on a single glass plate. The resulting images were mounted on paper and separated into rectangular cards, six by nine centimeters, the size of a traditional calling card. Napoleon’s portrait was published in this format, launching the carte de visite craze that would go viral, nineteenth-century style, through Europe and the United States in the decades that followed. Before long, Disdéri was printing between three and four thousand photos a day, and hundreds of other studios cropped up throughout Paris and beyond to help folks share these early selfies with friends and family.

An uncut Disdéri sheet, around 1860

Precursor to Facebook, Instagram and the seemingly endless ways that humans have cultivated photographic technologies to connect socially in recent years, the carte de visite was a veritable fad in the second half of the nineteenth century just as these technologies were getting started. All of a sudden everyday folks could have their pictures taken in the same way as the wealthiest members of society, in yet another example of the democratizing, equalizing forces of nineteenth-century French culture. At the same time, the photograph went from an exotic, awe-inspiring phenomenon (think of how exciting and mysterious it must have been to see life reproduced in this way for the first time) to a flimsy, commonplace object.

![[Album_de_portraits_cartes_de_[...]_btv1b84329315](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1467878808i/19639920.jpg)

The sculptor Eugène Brunet, from Edouard Manet’s personal album of photo cards

The actress Cléo de Mérode, a collector’s favorite

Disdéri’s inexpensive technique allowed a form of mass production that made the once incredible daguerreotype quickly obsolete, fading out as quickly as a Snapchat message. Soon celebrities were in on the game, and you could collect images of your favorite actress or writer just as you might now follow them on social media today.

Henry Pointer’s image: cat meme, avant la lettre

Card-o-mania meant you collected your friends and acquaintances in photo albums (bound Tumblrs?), that is, unless you chose to organize them differently: by gender, age, or by profession. For most, the poses are standard, but look more closely and you see timid efforts at self-expression: the tilt of a head, the sideways stance, the choice of clothing. Some posed with their spouses, some with their pets, and every once in a while, you find something much more akin to a status update, the sign of someone who truly understood both the genre and its future possibilities.

July 4, 2016

Ancient Romans Excavate a Giant Skeleton in Morocco

By Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

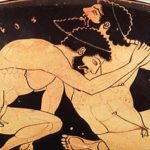

When the Roman commander Quintus Sertorius arrived in Tingis (Tangier, Morocco) in 81 BC, the locals showed him a huge mound said to be the grave of Antaeus, the city’s famous founder. In Greek myth, Antaeus was a giant of North Africa notorious for his compulsory wrestling contests. Every opponent succumbed to his lethal grip. That is, until the Greek strongman Heracles took up the challenge and slew Antaeus. According to the locals, Heracles then took up with Antaeus’s giant widow, Tinga, and fathered Sophax, the city’s first king.

Skeptical, Sertorius ordered his soldiers to dig up the mound.

Sertorius was so gob smacked by the enormous skeleton that emerged under the men’s shovels that he personally affirmed the Tingis legend and reburied the giant Antaeus with great honors. According to Plutarch’s biography of Sertorius and the geographer Strabo, the skeleton in the mound was 60 cubits long, about 85 feet (26 meters).

Modern commentators have sarcastically dismissed the possibility that the Romans could have discovered such a vast skeleton. They assert that Plutarch’s narrative simply shows how Sertorius cleverly manipulated the beliefs of the ignorant Moroccans.

But until now, no one troubled to check the paleontology of North Africa. In fact, the Antaeus incident is an important milestone in paleontological history. Sertorious’s investigation of the Tingis folklore claim is the earliest recorded deliberate excavation of the significant Pliocene-Miocene (Neogene) fossils of Morocco. The local story about the giant Antaeus was consistent with the traditional geographical distribution of the extinct race of giants in Greek mythology, and it also turns out that the location of immense bones’ corresponds to actual fossil beds in the region.

Ancient historians Gabinius and Strabo tell us that the giant was unearthed in Lixus (modern Larache) about 40 miles south of Tingis on the Atlantic coast. Pliny also placed Antaeus’s remains in Lixus, but refused to write down any of the region’s “fantastic” legends, complaining that the native words “are absolutely unpronounceable.”

So what kind of skeleton was identified as the giant Antaeus? In 1806, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier pondered this Roman event and suggested that the remains might have belonged to a whale. Cuvier also remarked that, based on his studies, the ancients “often exaggerated giant skeletons by eight or ten times the size of the largest fossil elephant.” If we apply Cuvier’s formula, we might guess that in reality the skeleton was about 9 feet long. This matches the size of species in the rich fossil bone beds around ancient Tingis and Lixus. The remains include Pliocene-Miocene elephants (Tetralophodon longirostris, Anancus), the early mammoth M. africanavus, and giant giraffids (as well as Eocene whales, which could measure up to 70 feet long). Any of those skeletons would stagger the ancient imagination. (It may be worth mentioning that stupendous dinosaur remains lie in the Atlas Mountains, about 150 miles (250 km) southeast of Lixus. But it seems unlikely that these could have been transported to the coast in antiquity.) It seems safe to conclude that the true identity of the huge bones identified in 81 BC as the mythic giant Antaeus belonged to an extinct mammoth that lived 23-3 million years ago.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times, Fossil Legends of the First Americans, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World.

June 27, 2016

Trapping the Tiger of Mysore

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Portrait of Tipu Sultan, artist unknown

In 1799, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War came to an end when Major-General David Baird (1757-1829) led the final British assault on Seringapatam, the island citadel that served as a capital for Tipu Sultan, the self-proclaimed “Tiger of Mysore”.

Seen in retrospect, it is easy to forget how precarious Britain’s position in India was in the eighteenth century. The British East India Company was only one of several regional powers that competed to fill the power vacuum left by the disintegrating Moghul empire. One of the most powerful of the Company’s rivals was the Muslim state of Mysore in south-central India.

When the dynasty’s founder, Haider Ali, seized Mysore from its Hindu ruler in 1761, the British saw the new kingdom as a buffer against the powerful Nizam of Hyderabad. They soon changed their minds. Haider Ali and his son, Tipu Sultan, adopted two goals that put them in immediate conflict with the East India Company: aggressive territorial expansion and diplomatic ties with post-revolution France.

The East India Company’s rivalry with Mysore took on new urgency in 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt with the avowed intention of driving the British out of India. The possibility that France would attempt to reclaim a base in India seemed all too likely. British India buzzed with rumors that the French had joined forces with the Tiger of Mysore.

In February, 1799, those rumors were confirmed. British agents in Madras claimed to have intercepted a letter from Bonaparte to Tipu Sultan. In it, Britain’s number one enemy offered aid to his Indian counterpart, “Citoyen Tipou”: “You have already been informed of my arrival on the borders of the Red Sea with an innumerable and invincible Army, full of the desire of delivering you from the Iron yoke of England.” Scholars have long doubted the authenticity of the letter. Genuine or not, it provided the trigger that Richard Wellesley, the East India Company’s Governor-General, had been waiting for.

Forty thousand East India Company and Crown troops invaded Mysore on March 5th. The armies moved quickly across Mysore in a two-pronged pincer attack from the British strongholds of Madras in the east and Bombay in the west. Their goal was the fortified island citadel of Seringapatam.

On May 4, Major-General David Baird led the final charge against the walls of Seringapatam. According to his biographer, Theodore Hook, the general volunteered to lead the assault in order to “pay off old scores”. Volunteer or not, Baird was a sentimental favorite for the job. Twenty years early, he had spent four years as a captive of Tipu Sultan following the British defeat at Pollilur in 1780.

Once British cannons opened a breach in Seringapatam’s outer wall, Baird’s force crossed the surrounding river under a barrage of musket fire, fought their way into the gap, and took the ramparts. The main body of British and Indian forces followed. Two and a half hours later, Seringapatam was under British control.

David Wilkie. Sir David Baird Discovers the Body of Tipu Sultan in the Ruins of Seringapatam.

That evening, Baird played the central role in another event that captured the British imagination. Acting on reports that Tipu Sultan had been killed in the assault, Baird sought out the Indian ruler’s body under a pile of corpses in a gateway that had been a focus of the Mysore defense. Major Alexander Beatson, official historian of the campaign, summed up the moment as seen through Victorian eyes:

“He who had left the palace in the morning a powerful imperious Sultaun [sic], full of vast ambitious projects, was brought back a lump of clay, abandoned by the whole world, his kingdom overthrown, his capital taken and his palace occupied by the very man, Major-General Baird, who,,,had been..in irons, in a prison scarce three hundred yards from the spot where the corpse of the Sultaun now lay.”

By any standard, Baird’s “old scores” had been paid in full.