Holly Tucker's Blog, page 16

April 25, 2016

The Original Assassins

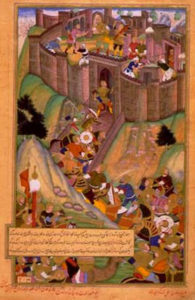

The Assassins’ mountain fortress at Alamut

The original Assassins were members of a revolutionary Shiite splinter group founded in eleventh century Persia by Hassan Sabbah.

Like many schismatic religious groups (Islamic and otherwise), the Assassins believed that Muslims, including mainstream Shiites, had taken a wrong turn. Islam needed to go back to its foundations. As far as other Muslims were concerned, Sabbah’s beliefs were heresy. Among other things, he taught that Mohammad’s son-in-law, Ali, and the Shiite imams who succeeded him were incarnations of Allah.

Like anarchists in the early twentieth century, the Assassins had neither money nor political power so they turned to the public murder of important figures as a way of exercising influence over society. (Anarchists called this “propaganda of the deed”.) The cult was organized as a secret society. The goal was not the removal of specific political leaders, but making people believe that the Assassins could kill anyone at any time.

The sect was destroyed in 1256 when the Assassins made the mistake of trying to kill Hulagu, the grandson of the Genghis Khan and leader of the Mongol hordes. (If you want to assassinate a Chinggisid prince, you need to get it right the first time.)

April 19, 2016

The Tale of a Sword

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

By 1956, James Stannard, a plumber in North Dorset, Vermont, had suffered as much guilt as he could stand. As a U.S. Army lieutenant in occupied Japan during the months after World War II, his job had been to disarm civilians. On one occasion, he seized a fifteenth-century sword, crafted by the famed weapon maker Kanemitsu, that had been passed from one generation to the next within a Japanese family.

An ornate samurai sword in the collection of the British Museum. Photo by Andres Rueda, via Wikimedia Commons.

Members of the family were distraught. “They offered me a wad of yen, and that must have been a couple of thousand dollars, but I had my orders,” Stannard said. “I took the sword. As I was leaving their house in Nagoya, they begged me to treat it well. They told me to use nothing but vegetable oil on the sharp gleaming blade. When we were allowed to bring back a souvenir, I chose the sword to remind me of Japan. But it always reminded me of the man who begged that it be returned someday.”

Years passed and Stannard’s guilt grew. Aware that Northwest Airlines had a large operation in Japan, he asked the airline for help in finding the sword’s true owner. And Northwest succeeded in tracking down 59-year-old Isao Okuda of Nagoya. With Stannard’s consent, the company worked out a plan to return the sword, which was three and a half feet long and sheathed in sharkskin, to Okuda. Northwest employees took charge of the voluminous customs and police paperwork necessary to restore the sword to its nation of origin.

“The sword, tempered and still gleaming, was delivered in New York to stewardess Carole Kilander of St. Paul on today’s flight,” Ed Wallace of the New York World-Telegram and Sun wrote on January 16, 1957. “Miss Kilander will take the sword to Seattle and give it to another stewardess who will carry it on to Anchorage, Alaska. There it will be given to a third Northwest Orient air stewardess who will take it to Tokyo.”

Paul Bencoster, a Northwest staffer in Japan, met the plane and took part at the exit ramp in the reunion of the sword with its owner. “Captain Moore turned the sword over to myself, and I in turn handed it over to Mr. Fujiyama, representative of the Japanese government, who in turn turned it over to its original owner,” Bencoster wrote.

A few minutes later, in a press conference inside the airport, a swarm of reporters and cameramen watched the kimono-clad Okuda accept the sword a second time. “He then, with the sword in his hand, expressed his heartfelt appreciation to Northwest Airlines and finally shook hands with me for about five minutes, making a speech all the while, most of which I did not understand,” Bencoster noted, “but I presume he was again thanking me for the part NWA had played in the return of his family’s heirloom.”

Guilt assuaged.

This post is excerpted and adapted from Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines by Jack El-Hai, published by the University of Minnesota Press.

Further reading

Anderson, Jim. “Across years, across miles, sword returning home.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 21, 2013.

Turnbull, Stephen. Katana: The Samurai Sword. Osprey Publishing, 2012.

Emigrating from America

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

America is a country of immigrants. Literature and films like the recent Brooklyn depict the familiar story of immigrants arriving by ship, overcoming great difficulties, and eventually learning to embrace a new life full of promise. But the immigrant experience has also always included huge numbers of people who turn around and go home.

America is a country of immigrants. Literature and films like the recent Brooklyn depict the familiar story of immigrants arriving by ship, overcoming great difficulties, and eventually learning to embrace a new life full of promise. But the immigrant experience has also always included huge numbers of people who turn around and go home.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, more than half of the nearly two million Italian immigrants who arrived in New York returned to their homeland. The same was true for Greeks, Russians, and Eastern Europeans. The percentages of returned immigrants from England and Ireland were lower, but still amounted to over two hundred thousand returnees in the 15-year period for which records were kept after 1908.

Earlier waves of immigrants resulted in mass returns as well. Returning from his tour of America in 1842, Charles Dickens was surprised to discover nearly a hundred returning immigrants among his fellow-passengers. Curious to know their stories, he investigated “with what expectations they had gone to America, and on what errands they were going home, and what their circumstances were.” He learned of their disappointments, homesickness, illness, and poverty that had only been worsened by their travels, observing one starving wretch who was living on the “bones and scraps of fat he took from the plates used in the after-cabin dinner, when they were put out to be washed.”

Earlier waves of immigrants resulted in mass returns as well. Returning from his tour of America in 1842, Charles Dickens was surprised to discover nearly a hundred returning immigrants among his fellow-passengers. Curious to know their stories, he investigated “with what expectations they had gone to America, and on what errands they were going home, and what their circumstances were.” He learned of their disappointments, homesickness, illness, and poverty that had only been worsened by their travels, observing one starving wretch who was living on the “bones and scraps of fat he took from the plates used in the after-cabin dinner, when they were put out to be washed.”

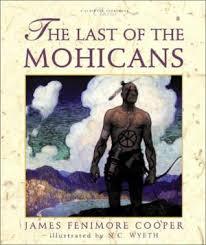

There is a vast ‘remigrant’ literature that has been largely unstudied. Much of it has been lost among the letters and family diaries stored in attics or boxed in dusty parish archives. Some disillusioned immigrants did publish their stories. William Clark, who arrived in New York in 1817 full of hope and curiosity about the new experiment in democracy that was America, was soon disappointed by the harsh conditions he encountered compared to the life he had left in England. He wrote a book intended to warn his countrymen, titled The Mania of Emigrating to the United States. David Mitchell came to America in 1848, as a young clerk seeking wealth and adventure. In his book recounting the experiences that led him to decide to return home, he warns against the temptations of the American myth. His description of the moment when he decided to leave England evokes the dream that the American landscape seemed to offer. In his case, it was a bestselling novel that drew him: “I was one day sitting at my small desk, in a little dark cage of a room, with no other business than to look out on the crowded thoroughfare. I had just finished The Last of the Mohicans. The mildness, the freshness, the freedom of the New World, its abundance of land and scope for enterprise and adventure, all delighted and tempted me.”

“I was one day sitting at my small desk, in a little dark cage of a room, with no other business than to look out on the crowded thoroughfare. I had just finished The Last of the Mohicans. The mildness, the freshness, the freedom of the New World, its abundance of land and scope for enterprise and adventure, all delighted and tempted me.”

For this immigrant like so many others, though, the experience of travel was ultimately an exercise in disenchantment, leading to a new appreciation of home. For those who left as for those who stayed, disillusionment and the maturity that accompanied it was an important part of the immigrant adventure. Most of us have still only heard half of their story.

For further reading:

Mark Wyman, Round-Trip to America: The Immigrants Return to Europe, 1880-1930 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1993).

Wilbur Shepperson, Emigration and Disenchantment (Norman, OK, 1965).

D. W. Mitchell, Ten Years in the United States (London, 1862).

William Clark, The Mania of Emigrating to the United States (London, 1820).

April 13, 2016

Museum Mysteries: Santa’s Epidemiology

By Tegan Kehoe (Guest Contributor)

One of the quirks of being a medical museum is that some of our most interesting stories are ones we are very glad not to be able to tell with artifacts. In 1966 a mysterious outbreak of Salmonella took place at Massachusetts General Hospital. Salmonella is not uncommon, but this particular type, Salmonella cubana, is rare. Some of the patients seemed to have contracted the bacterial infection while at the hospital. David Lang, a pediatrician, was determined to find the cause and stop the spread of the outbreak.

The first five cases were all in the same building, which suggested that there was a common source. However, a few weeks after Lang started investigating, S. cubana infections started showing up in completely different places in the hospital. Lang searched for a common factor. At the time each clinical building at the hospital had its own kitchen, so at first Lang didn’t think to look at the food, but then he learned that there was a special-diet kitchen that served all of the buildings.

From the hospital’s collection: cafeteria spoons.

Pictured are a few items from our collection related to nutrition and food services in the 1960s: two MGH cafeteria spoons and a sample 1960 menu. While almost all of the S. cubana patients had been on special diets at one point or other, rigorous testing determined that the kitchen wasn’t the source of the outbreak.

Lang stumbled on the answer in part because of an MGH tradition: Every December, for a grand rounds presentation, surgical residents create a fictional

A 1960 Mass General menu.

medical case and make up a chart for Santa Claus. Often he is hospitalized suffering from a host of holiday-related ailments – candy-cane scented urine and broken ribs caused by reindeer games are two that come to mind. Regardless of his condition, Santa always recovers and is sent home just in time for his Christmas Eve duties.

A lab technician remembered that the previous Christmas she had found bacteria that might have been S. cubana in Mr. S. Claus’s urine sample. It wasn’t real urine, and the pranksters who created it and a blood sample gave Lang their recipe – nothing in the urine concoction pointed to Salmonella. Months later, Lang was poring over the records of a young patient with S. cubana and he noticed the boy had been given a test using carmine dye. Lang didn’t know much about carmine, but he knew that it had been in Santa Claus’s blood sample. What if the two fake samples had been mixed up? He soon learned that carmine dye is made from the cochineal beetle, which could easily become contaminated with Salmonella when it is harvested.

Cochineal on a cactus. Credit: Ina Widegren.

Lang couldn’t tell whether all of the sick patients had been exposed to carmine – it was the kind of test that didn’t show up in a patient’s file unless it had unusual results. He tested the carmine dye itself, and found S. cubana. In partnership with the CDC, MGH doctors determined they could continue using carmine safely if it was heat sterilized in processing.

Many mystery outbreaks are never solved. It’s possible that without Santa Claus, this one would not have been solved either.

Tegan Kehoe is the exhibit and education specialist at the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital.

April 8, 2016

White Bread Matter: Sweet Snow, Sour Dough, and Yeasty Froth

By Thomas Parker (regular contributor)

Archestratos (4th century BCE) granted supremacy to Lesbos bread as the whitest and most refined: “Now the best to get hold of and the finest of all, cleanly bolted from barley with a good grain, is in Lesbos, in the wave-surrounded breast of famous Eresos. It is whiter than snow from the sky: if the gods eat barley groats then Hermes must come and buy it for them from there.” (trans. J. Wilkins and S. Hill)

The Town of Eresos, Lesbos

The triple characterization (white (refined), wave-washed (smooth), breast (billowy)) pumped Lesbos bread up as fit for the gods whereas, mostly in the ancient world, barley bread was derided as being amorphous, clumpy brown, and fit for the poor. Barley lacked the structural proteins of the gluten in wheat so, apart from the Lesbos example, those seeking high-rising fluffy breads that held their shape avoided it. But barley, not to be silenced, played a particularly interesting part nearly 2,000 years later in the French bread wars of the 1660s.

Debate in Paris at that time swelled around a controversy that pitted pain mollet (a fluffy white bread) against the traditional pain levain (compact and dense sour dough bread). The matter played out in terms of health on the surface, but was really one of country, class, Catholicism, and cash.

“Petit pain mollet” as it is known today. credit- La Petite Cuisine de Lilou

Pain mollet, whose name derives from its softer dough, was in part popularized at the end of the sixteenth century by Catherine de Médicis (the bread was alternatively referred to as “le pain de la reine”). It rose at a lively rate— worrisome, for some— due to the yeasts it employed. Those yeasts were barley malt yeasts sloughed off from the byproduct of beer, often from foreign lands, such as Flanders. For detractors of pain mollet, this “beer excrement,” corrupted the country’s staple, infecting it with an un-French drink derived from equally un-French lands.

Yeast itself had a sketchy past dating to the Bible and, before that, the Ancient Greeks. It teamed with life, but possessed disturbing potential to swell out of control (exactly as these pain mollet seemed to do). Mired in controversy, it was thought as spumy as it was insalubrious, salacious, and belonging to an unfinished, in-between state of bread matter.

Unleaved bread used for communion

Of course, sour dough also contained yeast, but the devil lay in the details. Sour dough was leavened with yeasts known as franc levain, or dough inoculated by wild yeasts captured in the air of wherever the flour and water was mixed. The yeasts were colonized in the dough, soured by lactobacillus organisms, and cultured as the starter to make fresh bread. “Franc,” in this context, referred to “cultivated” as opposed to wild, and suggested that some measure of control was exercised on the unruly yeasts.

The lexical context helped make the sour dough yeasts even more palatable. The word franc with respect to humans signified “free,” “sincere,” “true,” and “authentic.” Franc levain rose slower and was not as fluffy, but it was redeemed as being at once wild and cultivated, free and controlled. Most of all, as the name suggests, franc was French, and not built on the sketchy byproduct of some foreign brewery.

To say a federal case was made of it would be to say too little. The Lieutenant General of the Paris Police asked the Faculty of Medicine to weigh in. Forty-seven doctors condemned the bread from beer yeast as dangerous, but thirty-three gave it a pass. The detractors opined that foam thrown from beer was a pernicious influence that gave rise to worms. Furthermore, beer itself was unhealthy, made from corrupted barley or wheat, dirty water, and cocktails of unknown drugs.

Yeasty foam thrown off from beer fermenation

The pain mollinistes responded that the Gauls had been using beer yeast to make bread for centuries, and that Pliny had observed as much in his Natural History (79 CE). The pain levainistes conceded that the Gauls had once used beer yeasts to make bread, but countered that it was by refining their ways that they ceased to be barbarians, leaving the unseemly bread practice behind. Indeed, it was the Franks who civilized the Gauls and made them properly “French.”

In the end, neither side totally won out. Brewer’s yeasts (barm) did, after all, make bread rise faster and higher, (truth be told, the economic factor of the bread wars had always been more central than health, country, and morality). Yet, perhaps the most savvy of the bunch were bakers who, in no small number, began to combine a bit of barm in their sour dough mixtures, playing both sides of the coin to make prodigiously endowed fluffy bread that remained “authentically French.”

For more on the history of the controversy, see Steven Kaplan, The Bakers of Paris and the Bread Question, 1700-1775 (Duke University Press, 1996)

April 6, 2016

Around the World in Eighteen Pages

by Rachel Mesch, Wonders & Marvels contributor

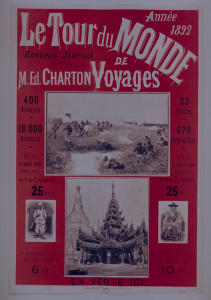

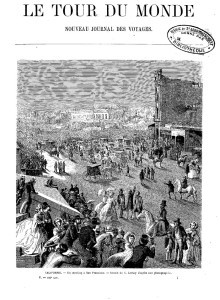

There is perhaps no artifact more telling of the nineteenth-century French imagination than the popular journal Le Tour du Monde (“Around the World”), a biweekly collection of travelogues launched in 1857 by journalist and publisher Edouard Charton. Long before most readers could dream of embarking on long distance travel, Le Tour du Monde provided virtual tours of far-off lands around the globe through detailed narratives written by intrepid explorers. As with Charton’s previous venture, L’Illustration, which would go on to provide up-to-date news animated by vivid visuals for over a hundred years, Le Tour du Monde was rich with images — from life-like sketches to haunting photographs by the century’s end.

You will no doubt recognize some names from the all star roster of bylines that graced the pages of this publication: Charles Darwin; Sir Richard Francis Burton; Anthony Trollope; Pope Pius X (when he was still Giuseppe Sarto), to name a few. Darwin’s tales from his trip to the Galapagos appeared in 1861, thirty years after his by then famous naturalist voyage had departed on the HMS Beagle and inspired his groundbreaking scientific theories. Most other dispatches were published two to three years after the traveler’s return.

Impressions of Antarctica, 1912

No matter: for the nineteenth-century armchair traveler, the slim dozen-and-a-half page pamphlets were gripping accounts of encounters otherwise unimaginable, welcome details of lives and landscapes that expanded one’s perspectives on the world. Before handheld cameras, before the internet, before distance travel was possible for all but the privileged few, to explore the world was a form of cultural heroism: the authors had often survived extremely dangerous conditions in order to explore new frontiers and translate them into words and images. It was here that readers encountered the recently discovered source of the Nile River, and where Jules Rouch (under the pen name M. Clément Alzonne) offered some of the first first-hand impressions of Antarctica.

A cover from 1862 depicting “a meeting in San Francisco.”

Le Tour du Monde is a telling artifact also because it reminds us of the role of the nineteenth-century mass press in the dissemination of new knowledge; of how it helped such knowledge to become a new form of entertainment; and of how the lines between science and fiction blurred in the process, even—and perhaps especially—in pages filled with seemingly straightforward details, ethnographic accounts, graded maps. Indeed, at a time of exponential cultural change—the moment when modernity was simultaneously happening and being invented as a concept, Le Tour du Monde refracts a cultural thirst for new and unknown places while also all too vividly reflecting its dangers. Seen through these pages, the nineteenth-century world expands and shrinks simultaneously: everything outside of France, from Ireland to the Americas to the Far East to Africa, is treated with the same exoticizing eye.

Perhaps most startling is the perspective on our American nation as a foreign land to be explored as any other: in one issue a visit to California records the mechanics of gold-mining alongside images of Chinese workers; the same issue couples this California adventure with a report from Athens, Greece. Sir Richard Burton reports on central Africa in one volume and the Mormons of Utah in another.

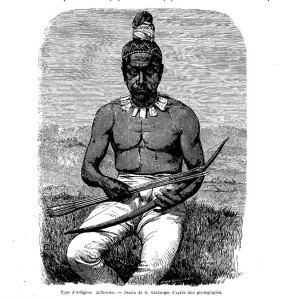

“Type of Indigenous Californian,” 1862

“Open Path to our African Empire” 1903

Nascent nineteenth-century prejudices and obsessions—from orientalism to colonialism to ethnocentrism–come together in these efforts to apprehend the Other in what proves to be staggeringly multiple forms, even as writers seek to erase their own presence in order to offer a “scientific” vantage point. Native species—plants and humans—are catalogued meticulously; maps are drawn, habits are described. And that air of science may be what is most dangerous of all: the very thing that authorized travelers like Arthur de Gobineau, who documented his 1859 travels to Persia for the magazine, to lay the seeds for his theories of racial superiority alongside anodyne descriptions of temples and unpaved roads; it may also have been the thing that prepared thousands of French readers who had devoured those travel accounts to accept such racial theories as truth.

Of course, Le Tour du Monde captures not just the demons of nineteenth-century colonialism, but also the dreams and fantasies of a generation, the excitement of a culture eager to learn and discover. Ethnology, sociology, archaeology, and biology appear in these pages as related nineteenth-century sciences driven by travel. And of course, there is the storytelling. As we read, we encounter the dreams that inspired Jules Verne to imagine his various fictional trips—Around the World, Under the Sea, to the Center of the Earth. Again and again we come into fresh contact with a passionate desire to know— through the eyes of the bold voyagers who ventured far in order to find out for themselves.

Of course, Le Tour du Monde captures not just the demons of nineteenth-century colonialism, but also the dreams and fantasies of a generation, the excitement of a culture eager to learn and discover. Ethnology, sociology, archaeology, and biology appear in these pages as related nineteenth-century sciences driven by travel. And of course, there is the storytelling. As we read, we encounter the dreams that inspired Jules Verne to imagine his various fictional trips—Around the World, Under the Sea, to the Center of the Earth. Again and again we come into fresh contact with a passionate desire to know— through the eyes of the bold voyagers who ventured far in order to find out for themselves.

To scroll through digitized versions of the journal yourself, go to the database Gallica.fr.

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.

April 4, 2016

The First Foot Fetishist?

Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

A foot fetish is a sexual attraction to naked feet. Of non-genital body parts, feet are the most fetishized. Not only is foot worship, podophilia, surprisingly prevalent, but it is a very ancient phenomenon. The earliest literary evidence comes from a set of 64 brooding, obsessive “Love Letters” composed in the second century AD; authorship is uncertain but the work is sometimes attributed to Philostratus. The love letters are bisexual, addressed to women and male youths.

Letter 18 “To a Barefoot Boy,” for example, insists that only the elderly, lame, and infirm need to wear slippers, sandals, and boots–and anyway leather tends to pinch, blister, and disfigure one’s feet. “Why don’t you always walk barefoot? . . . Let nothing come between your naked foot and the earth.” The dust will welcome your tread, declares, the lover, who vows to kiss the boy’s footprints and goes on to rhapsodize on the perfect shape of the beloved’s feet, comparing them to “new and strange flowers sprung from the earth.”

“Do not ever wear shoes!” the lover demands in Letter 36 “To a Woman.” Leave your feet bare like your neck and face, he pleads, without any cosmetics or adornments, not even chains of gold or silver. Be like silver-footed Thetis and newly born Aphrodite strolling barefoot on the shore. “Do not torture your feet, my love, and do not hide them . . . walk softly and leave prints of your own foot behind you, for those who would love to kiss them.”

Freud, true to his own obsessions, believed that sexualization of feet arose because they looked penis-like. But modern brain studies point to a neurological explanation for podophilia. In the human brain’s body-imaging map, feet and genitalia are adjacent areas. According to neuroscientist Vilanayar Ramachandran, director of the Center for Brain and Cognition, University of California, San Diego, foot fetishes appear to result from “cross-wiring in the brain between the two body parts.”

About the Author: Adrienne Mayor’s most recent books are The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014) and The Poison King (2010).

April 1, 2016

Captain Sturmy and the Spirit of Pen Park Hole

by Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

This is a tale that ‘amused the Country’ and been sent to the King of England and the Royal Society.

In 1669, some lead miners discovered a large hole at Pen Park, three miles from Bristol and three miles above the Severn. It was—in the words of a nineteenth-century historian—‘what women would call an ugly, deep, dangerous hole’.

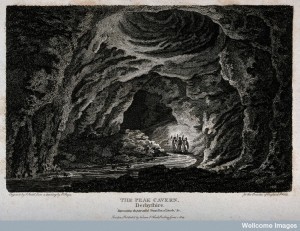

Geology: two visitors being shown the attractions of Peak Cave, 1803. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Captain Sturmy, an ‘inquisitive’ sea man who had published a book on navigation, decided to navigate the mysterious hole. Using ropes, he descended thirty-one full fathoms down, ‘into a large Place, which resembled to us the form of a Horse-shoo’. The cavern had a strange beauty: the floor was of white stone and enamelled lead ore, while the hanging stones were covered in saltpetre that ‘time had putrified’.

A large river in the cavern measured twenty fathoms broad and eight fathoms deep. In order to determine whether the water ebbed and flowed, they remained beside it for five hours, but there was no change. The water was fresh and sweet, clearly not sea water. They continued along the river for thirty fathoms, where they found ‘a great hollowness in a Rock’ thirty feet above them. The miner climbed up to explore the chamber, going in about seventy paces. Sturmy lost sight of him, but could easily hear when the miner ‘chearfully call’d’ that he had found ‘a Rich Mine’. Just then, the miner’s

joy was presently changed into amazement, and he returned affrighted by the sight of an Evil Spirit, which we cannot perswade him but he saw, and for that reason will go thither no more.

Miners and mine spirits—whether goblins or knockers—have a long history. Agricola, for example, referred to the popular Saxon beliefs about mine goblins in his De Re Metallica (1556); their presence was thought to indicate poor quality ore. Such beliefs were also common in Britain, with them being called knockers in Cornwall and goblins in Wales. British mine spirits were not necessarily evil or unlucky, unlike the German ones… or the one haunting Pen Park Hole.

The men remained several more hours, despite the scare, and climbed back up without difficulty. Four days later, Sturmy found himself ‘troubled with an unusual and violent Head-ach’, which he attributed to his time in the ‘vault’. He died soon after. The cavern seemed cursed, between Sturmy’s death and the ominous spirit; for years, nobody had anything to do with it.

This is where Sir Robert Southwell picked up the story in 1683. When Captain Collins, commissioned to undertake a coastal survey, sailed into port, Southwell knew he had found the man who might have the ‘courage’ to find the bottom of the hole. Collins had voyaged around the world, after all!

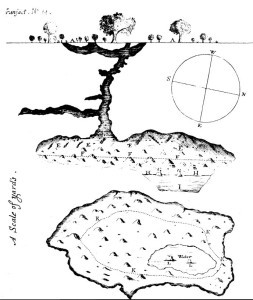

Pen-Park Hole. From the Phil. Trans. 1683, 13.

In September 1682, Collins and several of his men went exploring over two days. In total, though, they only spent a total of 3.5 hours in the cavern—a much shorter time than Sturmy and the miner. They were equipped with ropes and tackle, measuring lines, candles, torches… and a speaking trumpet. Collins and his team measured the cave much more precisely, finding, for example, that the entrance was only 39 yards (just under 20 fathoms). Collins was, indeed, able to measure the depth of the hole: 59 yards. The measurements for the body of water, which they found to be a pool surrounded by mud rather than a river, were much smaller: 27 yards long, 12 yards broad and 5 ½ yards deep. There was a suggestion, though, that the pool was sometimes much larger.

And as to the chamber above? It was not nearly so high nor deep. They found there only ‘Some appearances of Sparr, but nothing else in it except for some Bats.’

Despite their relatively short time below ground, the Collins party had ‘observed all things’, Southwell assured the readers of the Philosophical Transactions. The cavern was not even so deep that the speaking trumpet was needed to communicate with those above. And there was certainly no ghost in the upper chamber.

In effect, the Collins expedition had measured away all the mysteries of the deep that Captain Sturmy had found. The spirit of Pen Park Hole was truly dead.

Sir Robert Southwell’s account, which I’ve used, was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1683. For more details on Pen Park Hole today, see the website.

March 28, 2016

Fifty Years Before Hilary Clinton: Indira Gandhi

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Photo courtesy of the Dutch National Archives

Fifty years ago, on January 24, 1966, Indira Gandhi was sworn into office as India’s third prime minister. She was not the first elected female head of state–that honor goes to Sirivamo Bandaraniake of Sri Lanka. But Gandhi was the first woman elected to her country’s highest position who played a visible role on the international political stage.Like many women who assumed political power in the twentieth century, Gandhi followed in the footsteps of a powerful male relative. (Not Mahatma Gandhi! Gandhi was her married name.) As the only child of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister and a major player in India’s independence movement, Indira was active in politics from an early age. When Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri died unexpectedly of a heart-attack, Gandhi was appointed to office as a consensus candidate because the various male contenders for office could not agree among themselves. They assumed Gandhi would be easy to manipulate, but she proved to be anything but a docile place-holder. For three terms and twenty years, Gandhi was a powerful and controversial figure in Indian politics.

Whatever your political preferences, as Hilary Clinton comes closer and closer to the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, it is worth being reminded that the United States is a relative latecomer in terms of electing a female head of state.

March 21, 2016

Fractured Bones, Ancient and Modern

by Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Lately, I’ve had a lot of time to think about fractured bones. I broke my shoulder and ankle in a ski accident in February. During the long immobile days and weeks that followed, I tried to find ways to minimize self-pity, and one of those was to appreciate that I do not live in the seventeenth century.

I write about travelers who lived in that era, and I have often wished I could time-travel there. But not with a fractured shoulder. And fractured bones were not uncommon experiences for the people I study, who spent a lot of time on horseback, in carriages, or on ships – all means of transportation fraught with physical danger.

The only way to detect a fracture was to see it, feel it, or hear it. The great physician Ambroise Paré writes in his medical treatise that one must “handle the part which is suspected to be broken, and feel for pieces of bone severed asunder, and listen for a certain crackling of the pieces under our hands, caused by the attrition of the shattered bones.”

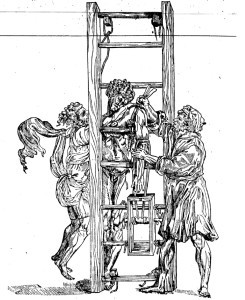

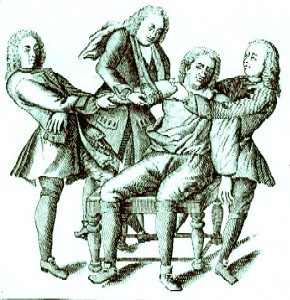

Here is a helpful illustration for one method of correcting a shoulder dislocation, from Guido Guidi’s popular sixteenth-century medical manual:

Treating bone fractures or dislocations often required strength on the part of the physician. Family members would be enlisted to help out. I’m glad this wasn’t a scene that had to be enacted in my household:

If you don’t need surgery to correct a bone fracture, though, the methods of treatment today are not all that different from what they were hundreds of years ago. Basically, the bone needs to be forced, put, or otherwise find its own way back into alignment (with the help of painkillers if you are lucky – codeine today, laudanum in the old days). The injured limb must be immobilized for at least a month, to allow healing and prevent further injury. Ambroise Paré lists the three most important steps in curing a broken bone: “First, restore the bone to its place. Second, contain or stay it being so restored. Third, prevent the increase of malign symptoms or accidents … including pain, inflammation, fever, abscess, and gangrene.”

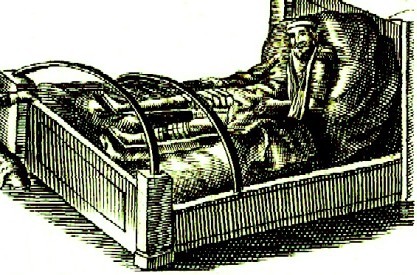

This illustration of bed rest is pretty much how I tried to sleep for the first month, with pillows around my splinted ankle instead of curved bars over the bed:

Today, what comes next in the long recovery phase is the stretching, pulling and bending imposed by a physical therapist if you want to be able to regain your lost mobility and strength. Medical manuals from antiquity through the 19th century don’t say much about this phase, so I can only assume that recovery from a shoulder fracture often meant that you were permanently hunched and stiff for the rest of your short life.

Still, despite the enlightened modernity of physical therapy, to the patient it can seem medieval. When I was at a recent session, another patient brought in this cartoon:

As Paré noted in his manual, it helps the healing to maintain good spirits. Those with a melancholic temperament have a harder time of it.

Illustrations from Armanemtarium Chirugicum Bipartitum by Johannes Scultetus (1666); Chirurgia è graeco in latinum conversa, by Guido Guidi (1554); A General System of Surgery by Lorenz Heister (1770); The Chyrurgeons Storehouse, by Johannes Scultetus (1653); New Yorker cartoon by David Sipress (2015).

For further reading:

Ambroise Paré, The Works of that famous Surgeon, Ambroise Paré, translated by Th. Johnson (1678).

Leonard Peltier, Fractures: A History and Iconography of Their Treatment (1990).

![By Unknown - [1] Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989 bekijk toegang 2.24.01.04 Bestanddeelnummer 929-0811, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37190788](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1459246275i/18585386.jpg)