Holly Tucker's Blog, page 18

February 14, 2016

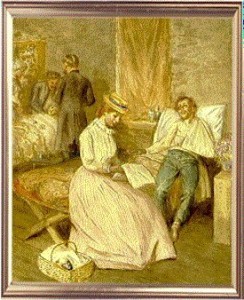

Romance in Civil War Hospitals?

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

On October 30, 1862, Anne Reading, a nurse stationed at Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, committed an unforgivable sin from Dorothea Dix’s point of view. She married one of her patients. Not surprisingly, Reading chose to keep quiet about the marriage. In March, someone told Miss Dix that Reading had gotten married. “Dragon” Dix was not pleased. Faced with Dix’s strong disapproval of nurses marrying patients or doctors, Reading reached the conclusion that it was time for her to leave the service.

Reading was not the only woman to meet her future husband while nursing. Ellen Sarah Forbes and Nancy M. Atwood both married men they nursed. (Like Reading, Forbes married while part of the nursing corps and left as a result.) Amanda Akin, Georgeanna Woolsey, and Annie Bell all later married doctors they met during the course of the war. One Sister of Charity left her religious order to marry one of her soldier-patients. The numbers were small, but Dix feared the people who opposed female nurses in the army would use them as proof that women entered the nursing corps only to find a husband.

It was a common charge. Cornelia Hancock told her niece Sallie that she was sure most people believed that husband-hunting was the reason she’d joined the army. Hancock acknowledged that if she were interested, it would be a good place to look since there were many nice men, and since soldiers were required to show respect to women. There were a number of women who spent the evenings gallivanting in just that pursuit. As for herself, she declared, “I do not trouble myself with the common herd.”

Elvira Powers, somewhat older, took the suggestion that she might look for a husband among her patients as a joke:

Once in my life did I have the audacity to pay special attention to a young corporal from Massachusetts by accompanying him to church one Sabbath evening, and came very near being discharged for the same. Shall never dare to repeat the heinous offense. Special attentions not allowed among Uncle Sam’s nephews and nieces. It is my opinion that said corporal is not over fifteen years younger than myself, still there’s no knowing what might have come of it.

She concluded, tongue-in-cheek, “Ah, me! What a sacrifice am I making for the good of my country.”

Powers might have treated the possibility as a joke, but any question that a woman’s virtue had been compromised was grounds for dismissal, even when proven false. Romance was strictly forbidden. The free-wheeling sexuality of a Hot-Lips Houlihan? Unthinkable.

****

We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win.

February 12, 2016

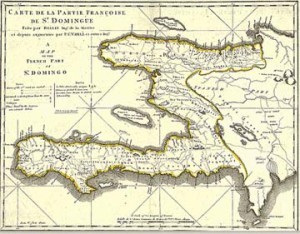

Pigs, Pirates, Sweetness, and Slaves (Pigs, Part Two)

By Thomas Parker (regular contributor)

Everybody loves stories of buccaneers, but few know about the original boucaniers, their relationship with pigs, and their role in seventeenth-century Saint-Domingue (today’s Haiti) where, as it turns out, pork was sweeter than sugar.

Today, the word “buccaneer” is a synonym for “pirate,” but there was a distinction to be made in the early colonial days of the French Atlantic. Unlike the flibustiers, their sea-faring brothers, the boucaniers were originally land-going. Instead of the swag of passing ships, the boucaniers hunted the wild boars left behind by earlier generations of explorers that had thrived in the overgrown reaches of Saint-Domingue.

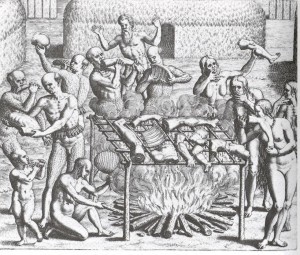

Though the boucaniers pursued pigs, and feral cattle, instead of people, their reputation was tarnished from the outset by their name, which derived from the grilling and smoking technique (boucaner) they inherited from the supposedly cannibalistic Caribbean Indian tribes who were said to use the boucan apparatus for smoking human meats.

Engraving by Theodor de Bry to illustrate Hans Staden’s account of his captivity in 1557.

The motley origins of the boucaniers further stoked the image. They included ex-slaves, engagés (men who paid their transport to the islands by working without pay for three years), shipwrecked sailors, and misfits who abandoned society for a life as errant as the wild animals they pursued.

Indeed, the boucaniers partially became the pig to capture it, smearing their bodies with pork fat to survive the island’s mosquito population, and sometimes only bettering their dangerous query by climbing trees and shooting from above to escape the charging boars. Men lost in the underbrush, as stories went, quickly turned wild themselves, taking wild pigs and dogs for companions and stomaching nothing other than raw meat as they crashed through the forest.

“Histoire des avanturiers qui se sont signalez dans les Indes,” Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin

In Exquemelin’s seventeenth-century account of pirate life, the author painted the boucaniers as dark-skinned with knotted, bristling hair, and sparse clothes dripping with animal blood. He described the men as mulattos of mixed black and white descent, or mestizos, combining white and Indian descent.

Yet, in counterpoint to the redoubtable image of mixed-raced origins and troubling animal-like savagery, the boucaniers were known for the egalitarianism and generosity they maintained amongst themselves, sharing their resources and working together to overcome the challenges of the hunting life, and the Spanish colonizers who attempted to eradicate their population.

Indeed, the real danger to the boucaniers came from the Spanish, who viewed them as interlopers in their colonized space. Through decades of skirmishes, the Spanish did their best to annihilate the boucaniers, chasing them off the trading positions where they sold meat and skins. The boucaniers and their sea-faring coastal brothers, the flibustiers, exacted acts of bloody vengeance, supplementing their lost incomes by attacking villages and pirating Spanish ships.

Illustration of a boucanier from Exquemelin’s book, looking decidedly more civilized than his description suggested

By the 1660s and 1670s, however, the landscape in Saint-Domingue was changing. The Spanish systematically annihilated the wild animals to cut off the boucanier food supply until the latter were left with two choices: permanently join the flibustiers or become agriculturalists (habitants). The first option was workable for many. As flibustiers, they could continue living a life of adventure, and their years of pig shooting had honed the boucaniers to be unparalleled marksmen, allowing them to decimate the target at sea from afar with their long-barreled guns (fusils à boucanier).

Slaves harvesting sugar cane

The less dangerous option was to quit life as a boucanier, clear land, and adopt an agrarian way of life by growing indigo, tobacco, and later, sugar. The life of the habitant was billed as more civilized. Indeed, one could hardly dispute that the men transforming from a wild communion with thick overgrowth, ambulatory lifestyles, and feral animals to the sedentary life of cleared spaces and domestic stock seemed more civilized.

And yet, as agricultural industry quickly made Saint-Domingue the most lucrative colony in the world in the century to follow, its labor-thirsty practices brought about a brand of slavery that spilled the blood of hundreds of thousands of African lives. It quickly became exponentially crueler than anything former pig hunters had practiced by a long shot.

February 8, 2016

The Language of God

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

I’m fascinated by the automatic fill-ins which search engines provide. For ‘Am I still…’ ‘Am I still a virgin?’ is a classic, along with ‘Am I still pregnant?’ and ‘Am I still in love?’ In all these cases I suspect that, if you need to ask, the answer is probably ‘No’. I was recently doing a little research into bilingualism in the ancient world, and typed in ‘What language did…’ in order to get a quick and dirty overview of ‘What language did Jesus speak?’ However, a suggested auto-fill was ‘What language did God speak?’

I’m fascinated by the automatic fill-ins which search engines provide. For ‘Am I still…’ ‘Am I still a virgin?’ is a classic, along with ‘Am I still pregnant?’ and ‘Am I still in love?’ In all these cases I suspect that, if you need to ask, the answer is probably ‘No’. I was recently doing a little research into bilingualism in the ancient world, and typed in ‘What language did…’ in order to get a quick and dirty overview of ‘What language did Jesus speak?’ However, a suggested auto-fill was ‘What language did God speak?’

I’d never thought about that – I’m not at all sure that it’s worth asking the question – but I decided to spend a few minutes on it. Well, Hebrew comes out as a front runner, not surprisingly. Then there’s the ‘It’s God we’re talking about, he’s omniscient, so that must include knowing all languages’.

Let’s leave that question aside for a moment and consider Jesus, around whose language competence there’s a rather more useful debate, although scholars remain divided as to which language, or languages, he would have spoken. I’m not sure who first came up with the line about the King James Bible, ‘If it was good enough for Jesus it’s good enough for me’, but one certainty is that he didn’t speak English, for the very good reason that the English language didn’t even exist at his time!

In the first century AD, in the area around Lake Galilee, Aramaic was spoken. How do we know that? Well, we can’t know for sure – there are no documents or inscriptions from Nazareth, and even if they were they’d show us the language or languages used for documents and inscriptions, rather than what people used for chatting to each other. The gospels are written in ancient Greek, but there were both Greek and Aramaic traditions about Jesus in circulation before the gospels we have were written down. In Mark 5:41, Jesus raises the daughter of Jairus from her apparent death with the Aramaic words ‘Talitha cumi’ meaning ‘Little girl, stand up’. Despite the occasional devout person trying to make out these words are from some special spiritual language, or even (worryingly) advising ‘Rely on the spirit of God for revelation, not on what you can find out by research’, it’s Aramaic. This young girl is the daughter of the leader of the synagogue, who would have been fine with Hebrew – so, is Jesus tailoring his language to his audience, or is this evidence that Aramaic was his first language? Or is the notion of a ‘first’ language entirely inadequate when we look at the multilingualism of the ancient world? Furthermore, embedded Aramaic words like these in the Greek text may not be ‘closer’ to the original words of Jesus, but simply show that the gospel-writer is using an Aramaic source here. And there was more than one form of Aramaic: Biblical Aramaic is not the same as Galilean or Palmyrene or Natataean. There were seven different Western Aramaic dialects at the time of Jesus.

And then there’s Greek, or at least the koine or ‘common language’ that was a simplified form of classical ancient Greek. The entire Greek Bible is now online for those who’d like to drill down into the meaning of the various translations. When Jesus talks to a Roman centurion, or to Pontius Pilate, this seems the most obvious language to use.

And what about Hebrew? It’s the language of most of the Dead Sea Scrolls, although some were written in Aramaic, but the community which produced the Scrolls wasn’t a mainstream group. However, in the gospels (Luke 4:16), Jesus ‘as was his custom’ attends the local synagogue and reads from the Hebrew Bible (our Old Testament). So he was fine with reading it. When Jesus was crucified, the notice on his cross – ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’ – was written in Greek, Latin: and Hebrew (John 19:20). Some modern translations give instead ‘Aramaic’ but the word used is hebraisti. There’s not much point writing it in Hebrew unless someone could read it. But no Aramaic, then? No language of the ordinary people? Should we read this as all Highly Symbolic – some Bible commentaries go for Latin as the language of politics, Greek as the language of the intellect and Hebrew as the language of religion – or as further evidence that Hebrew, or a version of it, was commonly understood in this part of the world?

But back to God. An anecdote told about the sixteenth-century Holy Roman Emperor Charles V goes like this:

The Castilian language is the finest of all Spain. Charles the Fifth said, that if he were to speak to God, he would speak in the Spanish tongue, by reason of its Gravity; to men, in French; to ladies, in Italian; to horses, in the German. Some Castilians have dared to say, either through a gayness of spirit, or as a Rodomontado, that God spake Castilian to Moses on Mount Sinai.

This comes from A New Survey of the Present State of Europe … by Gideon Pontier, done into English by J.B. Doctor of Physick, (London: W. Crooke, 1684, p.297); a rodomontado is a boast. As for French for men and Italian for women, presumably this reflects the language of the meetings the emperor attended (French) versus that of the social events which he also enjoyed (salons, literary events in which women could take part, used Italian).

So there you have it. God speaks the best language; of course!

Further reading:

Sang-Il Lee, Jesus and Gospel Traditions in Bilingual Context (de Gruyter, 2012)

Jim Adams et al. (eds), Bilingualism in Ancient Society (Oxford University Press, 2002)

The language of God

by Helen King (monthly contributor)

I’m fascinated by the automatic fill-ins which search engines provide. For ‘Am I still…’ ‘Am I still a virgin?’ is a classic, along with ‘Am I still pregnant?’ and ‘Am I still in love?’ In all these cases I suspect that, if you need to ask, the answer is probably ‘No’. I was recently doing a little research into bilingualism in the ancient world, and typed in ‘What language did…’ in order to get a quick and dirty overview of ‘What language did Jesus speak?’ However, a suggested auto-fill was ‘What language did God speak?’

I’m fascinated by the automatic fill-ins which search engines provide. For ‘Am I still…’ ‘Am I still a virgin?’ is a classic, along with ‘Am I still pregnant?’ and ‘Am I still in love?’ In all these cases I suspect that, if you need to ask, the answer is probably ‘No’. I was recently doing a little research into bilingualism in the ancient world, and typed in ‘What language did…’ in order to get a quick and dirty overview of ‘What language did Jesus speak?’ However, a suggested auto-fill was ‘What language did God speak?’

I’d never thought about that – I’m not at all sure that it’s worth asking the question – but I decided to spend a few minutes on it. Well, Hebrew comes out as a front runner, not surprisingly. Then there’s the ‘It’s God we’re talking about, he’s omniscient, so that must include knowing all languages’.

Let’s leave that question aside for a moment and consider Jesus, around whose language competence there’s a rather more useful debate, although scholars remain divided as to which language, or languages, he would have spoken. I’m not sure who first came up with the line about the King James Bible, ‘If it was good enough for Jesus it’s good enough for me’, but one certainty is that he didn’t speak English, for the very good reason that the English language didn’t even exist at his time!

In the first century AD, in the area around Lake Galilee, Aramaic was spoken. How do we know that? Well, we can’t know for sure – there are no documents or inscriptions from Nazareth, and even if they were they’d show us the language or languages used for documents and inscriptions, rather than what people used for chatting to each other. The gospels are written in ancient Greek, but there were both Greek and Aramaic traditions about Jesus in circulation before the gospels we have were written down. In Mark 5:41, Jesus raises the daughter of Jairus from her apparent death with the Aramaic words ‘Talitha cumi’ meaning ‘Little girl, stand up’. Despite the occasional devout person trying to make out these words are from some special spiritual language, or even (worryingly) advising ‘Rely on the spirit of God for revelation, not on what you can find out by research’, it’s Aramaic. This young girl is the daughter of the leader of the synagogue, who would have been fine with Hebrew – so, is Jesus tailoring his language to his audience, or is this evidence that Aramaic was his first language? Or is the notion of a ‘first’ language entirely inadequate when we look at the multilingualism of the ancient world? Furthermore, embedded Aramaic words like these in the Greek text may not be ‘closer’ to the original words of Jesus, but simply show that the gospel-writer is using an Aramaic source here. And there was more than one form of Aramaic: Biblical Aramaic is not the same as Galilean or Palmyrene or Natataean. There were seven different Western Aramaic dialects at the time of Jesus.

And then there’s Greek, or at least the koine or ‘common language’ that was a simplified form of classical ancient Greek. The entire Greek Bible is now online for those who’d like to drill down into the meaning of the various translations. When Jesus talks to a Roman centurion, or to Pontius Pilate, this seems the most obvious language to use.

And what about Hebrew? It’s the language of most of the Dead Sea Scrolls, although some were written in Aramaic, but the community which produced the Scrolls wasn’t a mainstream group. However, in the gospels (Luke 4:16), Jesus ‘as was his custom’ attends the local synagogue and reads from the Hebrew Bible (our Old Testament). So he was fine with reading it. When Jesus was crucified, the notice on his cross – ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’ – was written in Greek, Latin: and Hebrew (John 19:20). Some modern translations give instead ‘Aramaic’ but the word used is hebraisti. There’s not much point writing it in Hebrew unless someone could read it. But no Aramaic, then? No language of the ordinary people? Should we read this as all Highly Symbolic – some Bible commentaries go for Latin as the language of politics, Greek as the language of the intellect and Hebrew as the language of religion – or as further evidence that Hebrew, or a version of it, was commonly understood in this part of the world?

But back to God. An anecdote told about the sixteenth-century Holy Roman Emperor Charles V goes like this:

The Castilian language is the finest of all Spain. Charles the Fifth said, that if he were to speak to God, he would speak in the Spanish tongue, by reason of its Gravity; to men, in French; to ladies, in Italian; to horses, in the German. Some Castilians have dared to say, either through a gayness of spirit, or as a Rodomontado, that God spake Castilian to Moses on Mount Sinai.

This comes from A New Survey of the Present State of Europe … by Gideon Pontier, done into English by J.B. Doctor of Physick, (London: W. Crooke, 1684, p.297); a rodomontado is a boast. As for French for men and Italian for women, presumably this reflects the language of the meetings the emperor attended (French) versus that of the social events which he also enjoyed (salons, literary events in which women could take part, used Italian).

So there you have it. God speaks the best language; of course!

Further reading:

Sang-Il Lee, Jesus and Gospel Traditions in Bilingual Context (de Gruyter, 2012)

Jim Adams et al. (eds), Bilingualism in Ancient Society (Oxford University Press, 2002)

February 7, 2016

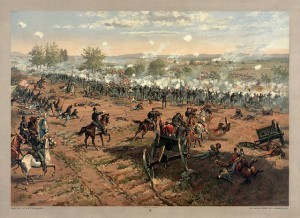

Cornelia Hancock: Civil War Nurse, Reformer, Muse

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

As the official superintendent of the Union Army’s newly minted nursing corps, Dorothea Dix had a clear vision of what her nurses should look like. Only women between the ages of thirty or thirty-five and fifty would be accepted. “Neatness, order, sobriety and industry” were required; “matronly persons of experience, good conduct or superior education” were preferred.

Dix turned away many able applicants because she thought they were too young, attractive, or frivolous. Twenty-three- year-old Cornelia Hancock, for instance, was preparing to board the train to Gettysburg with a number of women many years older than she was when Dix appeared on the scene to inspect the prospective nurses. She pronounced all of the nurses suitable except for Hancock, whom she objected to on the grounds of her “youth and rosy cheeks.” Hancock simply boarded the train while her companions argued with Dix. When she reached Gettysburg, three days after the battle, the need for nurses was so great that no one worried about her age or appearance. Too inexperienced to help with the physical needs of the soldiers, she went from wounded soldier to wounded soldier, paper, pencil and stamps in hand, and spent the first night writing farewell letters from soldiers to their families and friends. When wagons of provisions began to arrive, Hancock helped herself to bread and jelly, then divided loaves into portions that could be swallowed by weak and wounded men.

She quickly became accustomed to the realities of the battlefield, telling a cousin in a letter written on her second day in the field “I do not mind the sight of blood, have seen limbs taken off and was not sick at all.” In fact, she proved to be such a dedicated nurse that the wounded soldiers of Third Division Second Army Corps presented her with a silver medal inscribed Testimonial of regard for ministrations of mercy to the wounded soldiers at Gettysburg, Pa. -—July 1863. (She also had a dance tune named after her, the Hancock Gallop–a tribute that I suspect none of Dix’s middled-aged matrons received from the soldiers under their care.)

Hancock worked as a nurse for the rest of the war, tending the wounded after the battle of the Wilderness, Fredericksburg, Port Royal, White House Landing, City Point and Petersburg. She was one of the first Union nurses to arrive in Richmond after its capture on April 3, 1865.

After the war, Hancock helped found a freedman’s school in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, where she taught ex-slaves for a decade. (At one point those who objected to the concept of education for black children riddled the schoolhouse with fifty bullets.) When she moved back north to Philadelphia, she helped found the Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania.

Hancock became a posthumous best-selling author in 1937, when her charming and insightful letters from the battlefield were published under the title South After Gettysburg. They are now available under the title Letters of a Civil War Nurse–well worth the read if you are interested in Civil War nurses or daily life in a Union army camp behind the lines.

We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win.

February 3, 2016

Victor Hugo’s Breakfast of Champions

By Elizabeth Emery, Guest Contributor

For North Americans, the slogan “Breakfast of Champions” has become synonymous with Wheaties cereal and orange boxes endorsed by famous sports professionals such as Lou Gehrig and Bruce (now Caitlyn) Jenner.

For North Americans, the slogan “Breakfast of Champions” has become synonymous with Wheaties cereal and orange boxes endorsed by famous sports professionals such as Lou Gehrig and Bruce (now Caitlyn) Jenner.

These boxes can command hundreds of dollars on the collectibles market. But for the French, whose breakfasts more likely consist of a tartine (buttered baguette with jam), a croissant, or a slice of pain d’épice (gingerbread), such celebrity images tended to feature writers rather than sports personalities. A pre-1897 gingerbread slice at the Maison Victor Hugo in Paris, for example,  bears the famous writer’s likeness. It is just one of the many household Hugo collectibles such as soaps, liqueur bottles, tableware, and commemorative busts

bears the famous writer’s likeness. It is just one of the many household Hugo collectibles such as soaps, liqueur bottles, tableware, and commemorative busts that make up a section of the museum called the “musée intime.” An ongoing enterprise, today’s conservators continue to solicit contributions of Hugo memorabilia.

that make up a section of the museum called the “musée intime.” An ongoing enterprise, today’s conservators continue to solicit contributions of Hugo memorabilia.

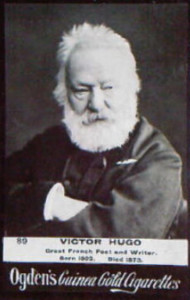

Although the commercial endorsement is considered a modern business practice, its roots run deep in the nineteenth century, when new technologies allowed for the widespread reproduction of celebrity images, thus spawning all kinds of unauthorized collectors’ items like those in the Hugo museum. Candy and tobacco companies  offered promotional items to draw consumers to their products, such as the baseball cards that would flourish in twentieth-century North America. Given the cultural weight of these trading cards and Wheaties sport “champions,” it is easy to forget that the phenomenon was also international and extended to many other kinds of celebrities, as in the series produced by Britain’s Ogden’s “Guinea Gold” cigarettes.

offered promotional items to draw consumers to their products, such as the baseball cards that would flourish in twentieth-century North America. Given the cultural weight of these trading cards and Wheaties sport “champions,” it is easy to forget that the phenomenon was also international and extended to many other kinds of celebrities, as in the series produced by Britain’s Ogden’s “Guinea Gold” cigarettes.

Hugo appears here, too, though this photograph was likely pilfered from photographer Paul Nadar, whose own postcard featuring this image circulated widely after Hugo’s death. Reproduced without attribution, Ogden’s also provided incorrect dates (1802-1885) and terrible image quality: the great man seems to have taken one puff too many.

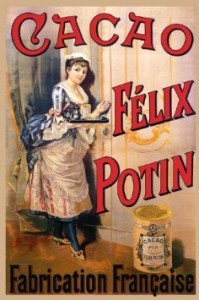

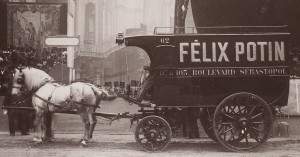

In turn-of-the-century France, the precursor to Wheaties and leader of the trading card phenomenon was Félix Potin, a grocery store chain founded in 1844 on the principle that buying in bulk and selling at fixed low prices, as did newly created department stores, could revolutionize the food sector (Walmart and Costco continue his experiments on a grander scale). As of 1870, the company offered home delivery; the horse-pulled trucks made the rounds of Paris emblazoned with its logo, thus making Félix Potin a household name. Capitalizing on new advances in printing technology and international marketing, the Potin family publicized its breakfast staples, such as hot chocolate, sugar, and jams, with brightly colored posters and postcards,

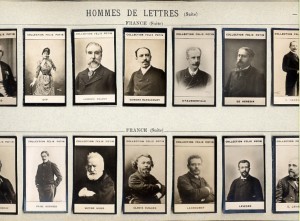

Capitalizing on new advances in printing technology and international marketing, the Potin family publicized its breakfast staples, such as hot chocolate, sugar, and jams, with brightly colored posters and postcards, and piqued public interest in celebrity photographs by offering collectible cards to customers with each 500-gram package of chocolate purchased. This technique was remarkably successful as a customer loyalty program. The 1898-1908 series featured 500 celebrities and the spaces to paste them were indicated in a blank photo album that encouraged consumers to complete the set. That’s 550 pounds worth of chocolate!

and piqued public interest in celebrity photographs by offering collectible cards to customers with each 500-gram package of chocolate purchased. This technique was remarkably successful as a customer loyalty program. The 1898-1908 series featured 500 celebrities and the spaces to paste them were indicated in a blank photo album that encouraged consumers to complete the set. That’s 550 pounds worth of chocolate!

A striking aspect of the Potin albums appears in the sheer variety of the international “champions” featured: while Wheaties focuses largely on sporting figures, the French series shows the late development of athletes as celebrity figures: of the thirty-eight pages only one (p. 38) is dedicated to international cyclists (the Tour de France began in 1903) and another half page (p. 37) is dedicated to fencers.  Writers and royalty are the single most important groups featured: foreign rulers and their families (7.5 pages), politicians (3), clergy (3/4), Army and Navy (2 3/4), lawyers (1), scientists and engineers (1.5), explorers (1/2), doctors (1), writers (7), musicians (2.5), painters (3.4), sculptors and architects (1), actors and singers (5). Hugo appears here in the writer section,

Writers and royalty are the single most important groups featured: foreign rulers and their families (7.5 pages), politicians (3), clergy (3/4), Army and Navy (2 3/4), lawyers (1), scientists and engineers (1.5), explorers (1/2), doctors (1), writers (7), musicians (2.5), painters (3.4), sculptors and architects (1), actors and singers (5). Hugo appears here in the writer section,

his tousled re-appearance from Nadar to Ogeden to Potin testifying to the international proliferation and unauthorized re-reproduction of such collector cards.

Today’s international interest in the collection of celebrity images, from the hype surrounding each new Wheaties “champion” and the promotion of Panini World Cup sticker albums, to more individualized “virtual” collections made possible by the arrival of Pinterest and Tumblr, follows the model set over one hundred years ago. The widespread appropriation, contemplation, and manipulation of “champions” demonstrates that—from breakfast table to blog—bric-a-brac-o-mania is alive and well.

Elizabeth Emery is Professor of French at Montclair State University. Author of Romancing the Cathedral: Gothic Architecture in Fin-de-Siècle French Culture (SUNY, 2011), Photojournalism and the Origins of the French Writer House Museum (Ashgate Publishing, 2012), and En toute intimité: quand la presse people de la Belle Epoque s’invitait chez les célébrités (Parigramme, 2015), among other works, she is currently writing a book about nineteenth-century French women collectors of Asian art under the auspices of a 2015 National Endowment for the Humanities grant.

Elizabeth Emery is Professor of French at Montclair State University. Author of Romancing the Cathedral: Gothic Architecture in Fin-de-Siècle French Culture (SUNY, 2011), Photojournalism and the Origins of the French Writer House Museum (Ashgate Publishing, 2012), and En toute intimité: quand la presse people de la Belle Epoque s’invitait chez les célébrités (Parigramme, 2015), among other works, she is currently writing a book about nineteenth-century French women collectors of Asian art under the auspices of a 2015 National Endowment for the Humanities grant.

Further reading:

On the striking collectability of Wheaties boxes see Steven Glew, “Cereal Box Price Guide.”

For more about the history of photography in nineteenth-century Paris see Elizabeth Anne McCauley, Industrial Madness: Commercial Photographs in Paris, 1848-1871 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

On the history of tobacco collecting cards see the New York Public Library exhibit and bibliography.

An overview of the Potin albums and digital reproductions of the images can be found here.

February 1, 2016

Putin’s Perfume: Scents of Great Leaders

Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

In January 2016, a new men’s fragrance went on sale in Moscow’s luxury department stores. Called “Leaders Number One,” the cologne was inspired by Russian strongman Vladimir Putin. The creation of Belarus perfumer Vladislav Rekunov, the scent comes in a sleek black flask decorated with Putin’s distinctive profile.

Selling for about 6,000 rubles (£57 or $95) the cologne is described as “not aggressive” but firm, attractive, warm, down-to-earth, and natural. The smell is a medley of pine cone, lemon, bergamot, musk, black currant, and, oddly enough, mung beans, often characterized as having a sour, “old man” whiff. The scent is intended to reflect Putin’s personality if not his personal body odor.

Test marketing indicates that the fragrance appeals more to women than to men.

Long before the discovery of pheromones and their role in sexual attraction, handkerchiefs suffused with perfumes or the essence of the beloved were treasured keepsakes. It was said that Henry VIII kept a handkerchief in his armpit and presented this perspiration-infused token to women he fancied as a flirtation ploy.

The notion that a sweet smell of success wafted from the bodies of alpha males can be traced back to the time of Alexander the Great. In his biography of the young world conqueror, Plutarch claimed that Alexander’s body gave off a pleasant, honeyed fragrance enjoyed by his closest companions.

With such a venerable history and now the bold debut of Putin cologne, is the world market ready for more essences inspired by great heads of state in the “Leaders Number One” perfume line? The possibilities are heady.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

January 31, 2016

Dorothea Dix Volunteers

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

“Dragon” Dix is a shadowy and controversial figure in the opening scenes of the PBS series, Mercy Street. The historical Miss Dix was just as controversial.

“Dragon” Dix is a shadowy and controversial figure in the opening scenes of the PBS series, Mercy Street. The historical Miss Dix was just as controversial.

For those of you who don’t have the details of the American Civil War at your fingertips: the war began at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861, when troops of the two-month-old Confederate States of America fired on Fort Sumter, in Charleston, South Carolina. Almost before the echoes of the first gun shots died away, President Lincoln called for 75,000 militia volunteers to serve for ninety days, certain that would be enough time to put down what he described as a state of insurrection, not a state of war. The public’s response was immediate and overwhelming. Men thronged the army’s recruiting offices. The first two Massachusetts regiments marched toward Washington and Fort Monroe two days after the president’s call; two more followed within the week. Individual states filled their recruitment quotas and offered more.

Citizen soldiers were not the only volunteers to respond to the president’s call. Even though Lincoln had said nothing about nurses—and had certainly not called for women to come to their nation’s aid—Dorothea Lynde Dix, a fifty-nine-year- old reformer dedicated to improving the treatment of prisoners, paupers, and the mentally ill, set out immediately to volunteer her services to create an army corps of female nurses to care for wounded soldiers.

By the time the Civil War began, Dix had spent twenty years working to change the way people thought about the mentally ill. She traveled almost continuously at a time when not many people traveled more than a few miles from home and women seldom traveled alone. Railroad companies gave her free passes, and freight haulers carried her packages to prisons, hospitals, and asylums at no charge. Most importantly, she had convinced politicians at every level of American government to support prison reform bills and to build insane asylums. She had even worked for reform at the federal level. In 1848, she lobbied for a bill to grant the states more than twelve million acres of public land to be used for the benefit of the insane, deaf, dumb, and blind. The bill passed both houses of Congress. President Franklin Pierce ultimately vetoed the bill, but Dix made important connections in Congress in its pursuit, a fact that meant her proposal for an army nursing corps got a fair hearing.

Dix was taking a well-deserved rest with friends in Trenton, New Jersey, when she heard the news that Sumter had fallen. Without hesitation, she packed her bags and left that afternoon for Washington, DC, on a trip that would be marked by troop movements, patriotic crowds, packed trains, wild rumors, and a secessionist riot in Baltimore.

When Dix reached Washington, the city was on high alert. Pickets guarded public buildings and bridges. Soldiers were billeted at the White House in anticipation of a Confederate attack before morning. A less determined woman might have have hesitated, but Dix went directly from the train station to the White House, where she volunteered her services and those of an “army of nurses,” yet to be recruited, to support the Union’s troops.

If any other woman had appeared unannounced at the White House with such a scheme, she might have been turned away. But Dix, soft-spoken and physically fragile but mentally tough, was preceded by her national reputation as a humanitarian, crusader, and lobbyist. She was used to working with powerful politicians, and they were used to working with her. Even with the threat of the Confederate army at the door, she and her proposal received a warm reception.

Dix’s offer to create an army corps of female nurses was revolutionary at the time. She envisioned a nursing corps of respectable women similar to that pioneered by Florence Nightingale but on a much larger scale. She shared Nightingale’s belief that a nurse should not simply be a doctor’s assistant but a patient’s primary advocate within the hospital, similar to the role she played for the mentally ill–an idea that would inevitably put Dix and her nurses in conflict with the doctors they worked with.

Three days later, Secretary of War Simon Cameron accepted Dix’s offer, without taking the time to define what her position would entail or how she would fit into the military medical bureaucracy, which was itself in a state of transformation. The Army’s Medical Bureau immediately began to attempt to undermine her authority, a process made easier by the fact that she lacked both administrative skills and tact.

Dix had always worked alone. As a lobbyist, she knew how to work the political system. As a reformer, she knew how to inspire action in others. But she had never run an organization, and she didn’t try to run one now. Instead she treated the nursing corps as a web of personal relationships with herself at the center. With no organization to back her up, she handled every detail herself, and was seemingly incapable of distinguishing between the important and unimportant. She had no system in place for finding and approving nurses. George Templeton Strong, definitely not a fan of “Dragon” Dix, summed up her personality accurately as “energetic, benevolent, unselfish and a mild case of monomania; working on her own hook, she does good, but no one can cooperate with her for [she] belongs to the class of comets, and can be subdued into relations with no system whatever.”

Despite her personal limitations and all attempts by the Army’s medical bureau, hostile surgeons or independent nurses to undermine or sidestep her authority, over the course of the war Dorothea Dix appointed more than three thousand nurses, roughly 15 percent of the total who served with the Union army, and more than any other person or organization involved with nursing in the Civil War.

We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win.

January 28, 2016

Royal Sparkly Things (Or Hairballs)

By Carlyn Beccia (Guest Contributor)

Wearing this beautiful stone could be a real conversation starter. Not just because it was once worth a small fortune, but because you would basically be wearing a gigantic hairball around your neck. The above is not some ordinary sparkly thing, but a bezoar stone. Bezoar stones are made when undigested food, hair and other yuckiness get stuck inside a goat or other ruminant animal’s stomach where lime, magnesium and other minerals accumulate. For centuries, royals would swallow bezoar stones or put them in their wine glass. Yum.

Wearing this beautiful stone could be a real conversation starter. Not just because it was once worth a small fortune, but because you would basically be wearing a gigantic hairball around your neck. The above is not some ordinary sparkly thing, but a bezoar stone. Bezoar stones are made when undigested food, hair and other yuckiness get stuck inside a goat or other ruminant animal’s stomach where lime, magnesium and other minerals accumulate. For centuries, royals would swallow bezoar stones or put them in their wine glass. Yum.

What could be worse than swallowing a hairball from a goat’s gut? Poison could be a whole lot worse. From 822 AD to the late sixteenth century, it was believed that you could drink any poison if you had a bezoar stone (it’s name literally means “to protect against poison”). Bezoar stones were worn in rings and necklaces to provide a quick antidote for poison. One was even placed in Queen Elizabeth I’s crown.

What could be worse than swallowing a hairball from a goat’s gut? Poison could be a whole lot worse. From 822 AD to the late sixteenth century, it was believed that you could drink any poison if you had a bezoar stone (it’s name literally means “to protect against poison”). Bezoar stones were worn in rings and necklaces to provide a quick antidote for poison. One was even placed in Queen Elizabeth I’s crown.

The Royal Treatment

When King Charles II was on his deathbed, his doctors were convinced that stuffing a bezoar stone down his throat would get him back on his feet. Unfortunately, the king’s condition only worsened to the point where he had to apologize for taking so long to die.

There’s a Hairball in my Soup

King Charles IX of France was so confident of the bezoar’s stones powers that he had his doctor poison his cook and then give him a bezoar stone as an antidote. The cook was dead seven hours later. This experiment proves that anything stuck in a goat’s stomach should probably stay there. Right? Not exactly. Bezoar stones contain a mineral called Brushite (Sodium Hydrogen Phosphate) that counteracts poisoning by exchanging phosphate for arsenate thereby absorbing the poison. Unfortunately, bezoar stones only works with arsenic. Charles’s doctor either did not use arsenic or bought a seriously, bad bezoar stone.

Carlyn Beccia is an award winning children’s book author and illustrator. Read more about history’s wackiest cures for common kid ailments and test your medical smarts in her book, I Feel Better with a Frog in my Throat.

Carlyn Beccia is an award winning children’s book author and illustrator. Read more about history’s wackiest cures for common kid ailments and test your medical smarts in her book, I Feel Better with a Frog in my Throat.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in November 2011.

January 25, 2016

“Our Army Nurses”

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

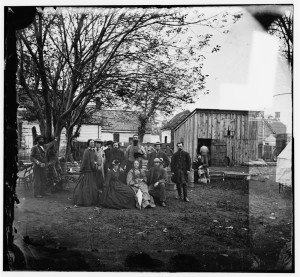

Doctors and nurses outside Fredericksburg after the Battle of the Wilderness. 1864

About a million years ago, I wrote a study guide to Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage for a reference book called The Literature of War. In the course of my research, I was introduced to the flood of material produced about the American Civil War some twenty or thirty years after it ended: regimental histories, general histories, poetry, pamphlets, biographies, lightly edited diaries and, most of all, memoirs by war veterans. Many war memoirs were small privately printed works distributed to friends and family. At the other end of the spectrum, The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (1885) was one of the best selling American books of the nineteenth century.*

The popularity of the genre provided me with a new way of thinking about the Civil War and useful context for writing about Crane. When I was done, I tucked it away in the back of my brain with all the other miscellaneous bits of information I collect as a writer of popular history and moved on to my next assignment.

I didn’t think about the specialized narrative of the Civil War memoir again until I got the call about writing The Heroines of Mercy Street. It had never occurred to me that Civil War nurses also wrote memoirs–it didn’t come up in the course of my research on Crane.** Boy did they ever! The first to appear, and probably the best known, was Louisa May Alcott’s Hospital Sketches, a lightly fictionalized account of Alcott’s brief stint as a Civil War nurse that was published in 1863 while the war was still in progress. But she was by no means alone. After the war, women in the North and South alike wrote their memoirs and edited their letters for publication, with titles like Ministering Angel, An Army Nurse in Two Wars, The Lady Nurse of Ward E, Hospital Pencillings, etc.

When the study of women’s history began to gain solid ground in the 1980s and 1990s, many of these works were reprinted, along with previously unpublished collections of letters. I am now the owner of a small collection of well-thumbed reprints; some with scholarly introductions and footnotes, others as naked of scholarly apparatus as the day they first left the printers. Charming, funny, heartbreaking–they’re worth reading if you are interested in different perspective on the Civil War.

One of my favorite Civil War nursing memoirs will probably never be reprinted: Our Army Nurses. Interesting Sketches, Addresses and Photographs of nearly One Hundred of the Noble Women Who Served in Hospitals and on Battlefields during Our Civil War, compiled by Mary A. Gardner Holland. The book is exactly what it sounds like: one hundred short accounts written by Civil War nurses roughly thirty years after the fact. Holland took on the task of tracking down as many former nurses as possible and asking them to contribute. She received more letters and photographs in response than she could include. Some of them are beautifully written–most notably Holland’s own essay. (I suspect her desire to write her story inspired the project.) Some of them suggest that their authors seldom picked up a pen for any purpose other than labeling jars of piccalilli and chow chow at the end of the summer’s canning. All of them display pride in their service. And well they should.

We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win.

*Thanks in part to a clever marketing campaign devised by its publisher, Mark Twain. Grant finished the book only a few days before he died. Twain sent 10,000 sales agents across the North, many of them Civil War veterans dressed in their old uniforms. They sold the two-volume memoir by subscription, using a script written by Twain himself, which was designed to appeal to veterans mourning Grant’s death. Twain described the work this way: “this is the simple soldier, who, all untaught of the silken phrase-makers, linked words together with an art surpassing the art of the schools and put into them a something which will still bring to American ears, as long as America shall last, the roll of his vanished drums and the tread of his marching hosts.” Some of Twain’s praise may be sales puffery, but Grant’s work remains highly regarded for its shrewd and intelligent depiction of the war.

**Women are largely invisible in traditional military history and its spin-offs. Something I want to help change.